Fujimoto Kazuisa

I Nothing Novel About Sarkozy’s ‘New France’

The French mass media call President Nicolas Sarkozy’s political style “new.” It is true that he won the presidential election under the slogan of “severing ties” with the past, “advancing innovation” and “taking action” toward the creation of “a new France.” But actually, one look into the contents of Sarkozy’s professed reform tells us that it is no more than “conservative revolution” that combines new liberalism and new conservatism. The truth is that there is nothing new about it.

Let us look at major “reform” bills that the Sarkozy-led ruling party Union for a Popular Movement is trying to railroad with a majority of 323 seats in the 577-seat national assembly. Tax deduction for overtime work, and reduction of income, inheritance and gift taxes are pump-priming measures aimed at stimulating the economy by alleviating the burden of taxes of high-income earners and social insurance premiums of businesses.

As is the case with other industrialized nations, France is suffering from the hollowing out of domestic industry caused by a declining birthrate combined with advanced aging of society and globalization. Under such circumstances, these policies will only aggravate the financial situation and add to social insurance costs.

To deal with the situation, the administration came up with proposals to reexamine the increase in medical expenses to be borne by citizens and requirements to receive pension benefits. It also proposed to raise the rate of value-added tax (equivalent to Japan’s consumption tax) from 19.6 percent to 25 percent as a way to generate “social insurance costs.” ‘Social divide’ widening

Frankly speaking, such measures are an attempt to forcie ordinary citizens and the socially vulnerable to pick up the tab for the cost of social insurance that should be shouldered by companies and high-income earners. Even some members of the ruling party are criticizing the move as harmful to “consumption” and as an obstacle to economic development. But what is even more crucial than such conservative criticism is the trend of the “social divide” widening in France, which is a hierarchical society to begin with.

Rather than having the desired effect, a “small government” that abandons the redistribution of wealth leads to an increase in social costs in the form of social insurance and unrest based on assumptions about the benefits of international market competition. Moreover, it causes a nation to go downhill both in terms of financial affairs and social order.

The introduction of market mechanisms into the public sector is also notable. The bill to “secure minimum service of means of transportation at a time of strikes” undermines the effectiveness of strikes and virtually violates workers’ right to strike. Prime Minister Francois Fillon clearly stated that he would expand the idea of “minimum service” to schools. The privatization of postal services mandated by the European Union is also a matter of time.

Traditionally, French government employees in transportation, postal services and education have formed autonomous organizations. But these plans will destroy the unions of such workers. The proposed reforms will have an impact not only on government employees, but also on ordinary citizens as they will have less chance to object to the government and companies.

The government is also about to introduce the “liberalization of school districts” for elementary, junior and senior high schools as a way to encourage competition among schools and improve the quality of education.

Actually, it will only widen the gap between a handful of elite schools that cater to the children of rich families, and a far greater number of schools at the bottom of the educational pyramid that continue to struggle under poor conditions. There are growing apprehensions that equality in education, an ideal embraced by the republican system, would fall apart.

Meanwhile, “liberalization of universities,” which is likely to happen before other proposed reforms, will strengthen the dependence of universities on the government and capital.

The policy comprises the strengthening of the authority of university presidents, reduction of autonomy of faculty members, and the introduction of independent administration and private capital.

As a result of the introduction of market mechanisms, if schools raise tuition and mergers proceed, universities will complete the unequal educational process as a continuation of elementary, junior and senior high schools. Universities will widen the gap in academic learning and culture in accordance with the financial situation of families, further entrenching the hierarchal order.

New ministry targets immigrants

Such measures based on new liberalism are accompanied by police-state measures to complement them. If unequal competition based on market mechanisms becomes an established system, the structural disparity it causes gives rise to social discontent, which can eventually lead to social unrest. That is why policies based on market liberalism need a system to maintain law and order to control and gloss over gaps in society caused by them both in terms of law and morals.

President Sarkozy is trying to pass legislation to strengthen criminal punishment and publicize the names of repeat and juvenile offenders in defiance of opposition by many experts on legal and criminal affairs. Such a defiant attitude stems from the perspective of placing absolute faith in economic liberalism.

In 2005, while Sarkozy was minister of the interior, his comment about “social trash” triggered riots in suburban Paris. It is based on an extremely nihilistic view–which also suits his philosophy to strengthen supremacy–that it is inevitable that an economically liberal society produces social dropouts and a powerful mechanism is needed to “clean up” such “trash” that opposes the establishment.

From the time he was interior minister, Sarkozy has been pushing to strengthen the power of police and intelligence authorities. Recently, he has called for the installation of surveillance cameras to monitor activities on the streets, using the attempted terrorist attack in Britain as a pretext.

It has become increasingly clear that such plans and policies to restrict and eliminate immigrants and foreigners are two sides of the same coin. He created a new post in the Fillon Cabinet called the Minister of Immigration, Integration, National Identity and Co-development to concentrate authority concerning the acceptance and treatment of immigrants, refugees and foreigners, which had traditionally been under the jurisdiction of the Foreign Ministry and the Ministry of the Interior.

The new ministry shows he is treating the immigration problem as a “special” domestic issue. It also means that the establishment of public power that targets immigrants and foreigners is to maintain law and order, reminiscent of colonial policy in the past.

This reminds me of the way France maintained that the Algerian War of Independence was an “internal” problem and harshly suppressed Algerians, particularly Muslims, during the 1950s.

The workforce’s movements under capitalism gave rise to immigrant workers and their descendants. As such, they generate a discrepancy between capitalism and nationalism.

That is why French (and European) capitalism, and the French people and state, need to hide or suppress African and Islamic immigrants as the embodiment of their own political, economic and mental discrepancies. The trend is becoming increasingly apparent as pressure for competition grows, caused by liberal globalization.

II No room for immigrant families in new France

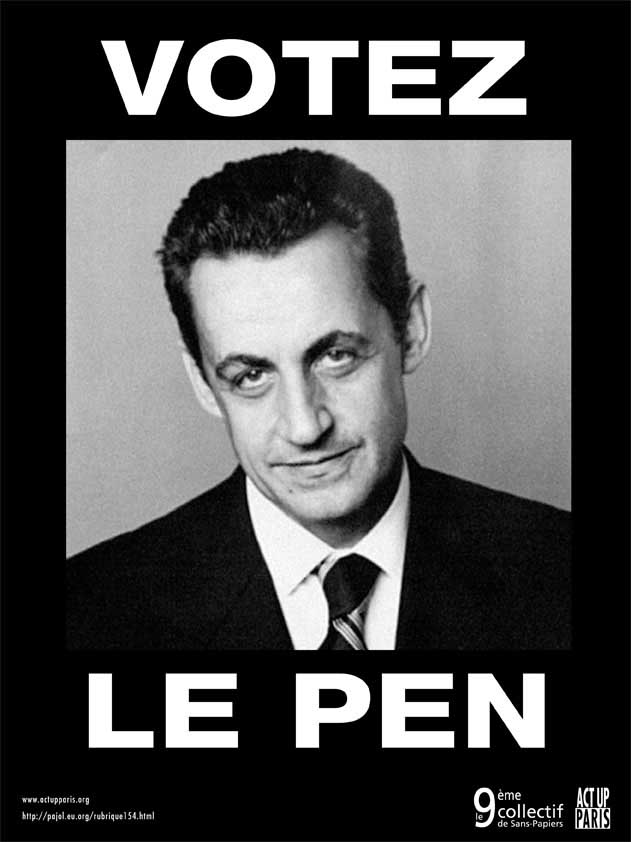

Nicolas Sarkozy’s victory in the French presidential election in May was mainly due to the fact that he won over voters of the extreme right who had supported Jean-Marie Le Pen in 2002. This time, Le Pen and his National Front Party suffered a crushing defeat in the presidential election as well as in national elections that followed. As a result, Le Pen and company virtually lost all political power.

Most French media touted Sarkozy’s win as a victory for French democracy. But such an assessment is deceiving. Le Pen’s defeat is proof that he is no longer needed. But why did he become unnecessary? It is because of the emergence of Sarkozy, who is more artful than Le Pen. The way the extreme right has become barely visible does not mean it is in decline. It means it has become established. The French republican system (citizen-oriented nationalism) once again finds itself face-to-face with Bonapartism, its Achilles’ heel.

Sarkozy’s slogans of “one France,” “the power of the people” and “unity for a common purpose without regard for left or right” captured the public. This is another sign of France’s inclination to the extreme right. Sarkozy, who supports the traditional French family system based on patriarchy and opposes PACS (Civil Pact of Solidarity), a form of civil union between two adults (same-sex or opposite sex), and homosexual adoption, is also a firm supporter of national morals and education. But the forcing of “French values” is linked with hostility toward immigrants, in particular Muslims, both ideologically and practically.

The Sarkozy law, which was strengthened last year, not only limits immigrants who are seeking French citizenship but also makes it impossible for immigrant workers to bring over their family members. (Sarkozy, who sings praise of family values, thus divides immigrant families.) When applying for residency permits for the families of immigrant workers, families are required to accept French values and show proficiency in French.

They are required to sign “a contract for acceptance and assimilation” and attend “citizen education” classes that teach “French values.” Furthermore, if their French ability is deemed substandard, they are required to attend a minimum of 200 hours of French lessons before proving their proficiency in the language. Such requirements make it virtually impossible for immigrants to bring over their families.

A main feature of “French values” is laicite, or secularism. A typical example of this thinking can be seen in the ban on Muslim girls wearing head scarves at school. But apparently, the same logic does not apply to Christians who are allowed to wear crosses. The policy is inconsistent and unreasonable. Secularism and the separation of religion and the state under a republican system bans government authorities from forcing specific religions on people. In reality, the idea is used to ban individuals from expressing their beliefs and faiths. I believe it shows the aberration or decline of the French republican system.

Carefree or guilt-free?

The problem with Sarkozy is his carefree nature that comes from his complacent hegemonism. The French word decomplexe is often used to describe Sarkozy’s attitude. It means complex-free, or having no qualms. Indeed, the way Sarkozy makes drastic decisions with a clear-cut manner about multifaceted, complex historical and social problems implies he is free from care. It gives the impression that he is energetic and lively. The media also seem to like the way he repeats phrases with strong impact while omitting complicated explanations.

But whenever rulers are decomplexe, citizens become complexe, or apprehensive. Sarkozy declared his intention to “wipe out social trash” and said: “People who live in France must love France. If they criticize French society, they should leave.” That’s a pretty carefree way of speaking. But praising him as a strong leader and touting him as a symbol of restoration of authority and a strong father figure is tantamount to overlooking the violence of elimination and integration that underlies such words and ideas.

Sarkozy’s refusal to conclude a “friendship treaty” with Algeria is a typical example. Algeria had hoped France would put words to its reflection on past colonial rule, if only a little. But its hopes were shattered by Sarkozy, who said “penance” is a religious term that he cannot accept as the president of a republican state which advocates the separation of religion and politics.

But the Algerian side has not once demanded that France use the term. Rather, it is Sarkozy, who brought it up and used it as an excuse not to sign the treaty. He said the building of a “constructive” relationship that looks to the future is more important than reflecting on the past.

The way he put it, one gets the impression that Algeria today, and in the future, is and will be free from the negative legacy of past French colonial rule. Coming from the side that colonized a foreign country, it sounds like nothing but opportunism, a threat or nihilism that takes advantage of one’s powerful position. This is the true nature of Sarkozy’s seemingly carefree style.

His defiant attitude can also be seen among the leaders of many industrialized nations, including the United States, Britain and Japan. Most of them are major powers that created empires in the past. In terms of political and economic ideology, it also forms the basis of new liberalism and new conservatism. Fortunately for France, labor unions (socialist), ordinary citizens (republican and democrat) and the immigrant community (advocates of the right to life and anti-establishment) still have the ability to criticize such ideology of defiance and social power to achieve genuine change.

A friendly media

Meanwhile, most influential French mass media, including “Le Monde,” are run and led by Sarkozy supporters. They tend to report favorably on his administration. (The dominance of the media is also a common characteristic of new liberal and new conservative politics that descend from the former administrations of British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and U.S. President Ronald Reagan and lead to the Sarkozy government.)

However, once France is able to politically bring its citizens together without dividing the underlying power of French society, it may be able to find a way out of the vicious circle of power-dominated realism. In that sense, the Sarkozy phenomenon can be likened to a litmus test of dominance and resistance in French politics and society.

Fujimoto Kazuisa, a specialist in modern French thought and associate professor of philosophy at Waseda University, is presently researching at the University of Paris.

This is a slightly edited version of an article that appeared in the International Herald Tribune/Asahi Shinbun on August 14 and 15, 2007 and at Japan Focus on August 15, 2007.