Eldad Nakar

Introduction

After serving as a Japanese diplomat in Asia and Europe during the first half of the 20th century—helping negotiate with the Soviet Union to purchase the North Manchurian Railroad, saving thousands of Jews from the hands of the Nazis in Lithuania, and being interned in the Soviet Union for a year at the end of World War II—Sugihara Chiune was told by his superiors to resign from the Japanese Foreign Service in 1947.

Following his resignation, he worked for a trading company in Japan and subsequently in the Soviet Union, while keeping the memory of his past to himself. The postwar Japanese state too has subsequently kept his memory out of the official record. (The purchase of the Manchurian railroad, which is inscribed in the records, contains no mention of Sugihara.)

One of the first stories about Sugihara to appear in the Japanese press was published in 1968, right after he was tracked down by Jehoshua Nishri, attaché at the Israeli Embassy in Tokyo and one of the beneficiaries of Sugihara’s acts. The national daily Asahi Shimbun reported that Israel had offered a full scholarship to Sugihara’s fourth son, Nobuki, to study at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, and told at length how Sugihara had saved Jewish refugees during the war (Asahi Shimbun, August, 2, 1968). But such coverage was rare, and resulted in no initiative to commemorate Sugihara or his actions in Japan.

Sugihara Chiune departed this world (July 31, 1986) for the most part in the way he came into it (January 1, 1900)—unknown to most of his countrymen. Much of what is known about him today in Japan was told after his death by his wife Yukiko, and his eldest son, Hiroki. Yukiko published a memoir in 1990. Choosing the title Rokusen nin no inochi no biza (Visas to save the lives of 6,000 people), she was determined that her late husband would be remembered in Japan for his acts to save Jews during World War II.

Once introduced, this story was told by others as well. Watanabe Katsumasa wrote three books on Sugihara, beginning in 1996. These are Ketsudan—inochi no biza (A decision—visas to save lives), Shinso Sugihara biza (The truth—Sugihara’s visas), and Sugihara Chiune—rokusen-nin no inochi o sukutta gaikokan (Sugihara Chiune: The diplomat who saved 6,000 people).

While Sugihara’s family and others were crafting Sugihara’s memory by writing, in the early 1990s his hometown, Yaotsu, decided to give his memory a more three-dimensional aspect. They set the wheels in motion to create a memorial place and time [2] for him. Within a few years a memorial site—consisting of a monument and a small memorial hall dedicated to Sugihara and his story—was built on a hill in town. Naming it the Hill of Humanity, and constructing a large park, the planners invited visitors to remember Sugihara by the catchword of humanism [3].

Soon newspaper articles were published on Sugihara’s life, television dramas [4] were produced, and even stories for children were generated. Yukiko and Hiroki themselves wrote such a children’s story in 1995, naming it Sugihara Chiune monogatari—inochi no biza arigato (Sugihara Chiune: Thank you for the visas that saved lives). The book by Watanabe Katsumasa mentioned above, Sugihara Chiune—rokusen-nin no inochi o sukutta gaikokan—is a manga story for children.

These projects, separately and together, form the foundations on which Sugihara’s memory is being shared, produced, and endowed with meaning in Japan. As Frances FitzGerald (1979: 16) has noted in regard to history textbooks, “what sticks to the memory… is not any particular series of facts, but an atmosphere, an impression, a tone”. Combined with certain details, such impressions have lent themselves to a basic narrative about Sugihara that may stick in people’s minds. This essay examines the commemoration of Sugihara in Japan and the basic story that sticks to mind, assessing the efforts to memorialize him.

Sugihara Chiune: The Basic Story as Told in Japan

Private Life

Japanese accounts of Sugihara Chiune’s life often begin with his birth on January 1, 1900, in a small town by the name of Yaotsu in Gifu prefecture. He was the second son in a family of five brothers and one sister. His mother was the offspring of a local samurai family. His father was the regional tax collector and was often absent from home because of his occupation. Chiune had close relations with his mother and was said to have complicated relations with his father.

From an early age he displayed interest in language studies, and upon graduating from the Nagoya Daigo, the equivalent of a junior high-high school, chose to study English further at Waseda University in Tokyo (1918). He did not complete his academic training, however. His father, who wanted him to become a doctor, did not approve of his decision to study English and cut his stipend. Having to work to support his studies, Sugihara was unable to continue for long. Spotting an advertisement by the Japanese Foreign Ministry, calling for candidates to learn foreign languages (English excluded), he applied and was accepted. In 1919 he took up Russian, and was soon assigned to Harbin in northeastern China for training.

From this moment on, most of Sugihara’s life would be spent away from Japan. In Manchuria, he acquired Russian language skills and became a Russian specialist (1919-1920; 1922-1924). During this period he also spent two years in the army as a soldier (1920-22); after being discharged, he worked in the Japanese embassy as a Russian translator (1924-1932) and later worked as an official in Manchukuo (1932-1936). He subsequently served in Europe on various national missions (1937-1945).

Before going to Europe, Sugihara returned to Japan briefly and met and married (in April 1936) his wife Yukiko (1913-). After their son Hiroki (1936-2001) was born, the three set off to Europe along with Yukiko’s sister, Setsuko. Their second son, Chiaki (1938-), was born in Helsinki, and their third son, Haruki (1940-47), was born in Kaunas, Lithuania [5]. The fourth son, Nobuki (1949-), was born following the family’s return to Japan (1947).

Public Life: World and National History Intersect

Commemorative accounts of Sugihara’s life always list the following two events:

Event I

The first event took place in Manchuria, just a few years after Sugihara finished his training and was posted in the Foreign Service of Manchukuo.

For some time, Japan and Russia had been competing to gain zones of influence and exploitation in and around China. This competition culminated in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905. Japan won the war and seized the opportunity to exploit Korea. Yet the race with Russia did not cease, as Japan was aiming also to control China’s northern frontier, which was abundant in natural resources including iron and coal. Armed skirmishes between Japan and Russia were routine in the early 1930s—especially after Japan established Manchukuo (1932). The Russian- owned Chinese Eastern Railway, which divided the area under Japanese control, was a major flashpoint. For a time, Russia and Japan held talks on a possible sale of the railway to Japan, but the talks stalled.

In 1933, Sugihara, a Russian expert, was assigned to the talks. With his knowledge of the Russian language and culture, Sugihara managed to acquire inside information regarding the actual condition of the railroad and thus its real value. Finally, the Russians accepted the Japanese offer.

This launched Sugihara’s diplomatic career. Noticing his abilities to collect intelligence and his capacity as a diplomat, the Japanese Foreign Ministry assigned him to posts in Europe that were close to the Russian border where he was assigned, among other things, to collect intelligence on Russia.

While in one of these posts, serving as the first Japanese consul in Lithuania—just before World War II broke out in the Pacific—Sugihara was involved in another major event.

Event II

By 1940, Europe—especially eastern Europe—was swarming with refugees fleeing the Nazis. Jews in particular desperately sought ways out of Nazi-controlled territories. Lithuania, which was still an independent entity—sandwiched between Nazi-controlled Poland and Russia—was a preferred destination for Jews. But as confrontation between Russia and Germany intensified, raising the prospect that either would seize Lithuania, Jews there sought ways to move on, out of danger. With western Europe under Nazi occupation, Jews attempted to travel east—beyond Russia. But Russian regulations required a transit visa from a third country. Jews began knocking on the doors of embassies and consulates in Lithuania—indeed, all over Europe—hoping to obtain transit visas in order to flee. Being denied visas by other consulates, they arrived in July 1940 at the doors of the Japanese consulate in Kaunas, Lithuania, which Sugihara Chiune headed.

Other diplomats had refused the refugees the documentation that would save their lives. Sugihara tried to consult his superiors in Tokyo on the matter, asking for instructions. To no avail. Japanese regulations regarding entry to Japan contained no special clauses concerning Jews; foreign nationals were all treated the same. To transit Japan, a third country visa and evidence of financial support were required.

Having been denied flexibility by his superiors, Sugihara chose not to abide by the regulations and to issue the transit visas for the Jewish refugees who requested them. Naturally, the issuances of a few visas led to an influx by other Jewish refugees who sought Japanese transit visas. Seeing the swelling number of Jews in front of his consulate, Sugihara did not lose heart but rather doubled his efforts to help the refugees. By this time, Russia had taken over Lithuania and ordered all foreign consulates to close. Knowing that he would soon have to close the consulate, Sugihara worked around the clock to issue as many visas as he could. He issued, in total, more than 2,000 such certificates for family transits; hence, the total number of Jews who were able to leave Europe by using them is said to have reached 6,000.

Anonymity

After issuing transit visas right up to the last minutes of his stay in Lithuania, Sugihara was assigned to other posts in Europe. For a while (1940-47), it seemed as though there would be no significant repercussions for his career. The end of the war found him serving as a translator for the Japanese legation in Romania.

In Romania he was captured by the Soviets and sent to a prisoner-of-war camp with his family. He returned to Japan (1947), only to be ordered to hand in a letter of resignation from the Foreign Service. He complied, thereafter moving from one odd job to another, even working in a department store for a while. Eventually he started using his Russian language skills, becoming a Russian translator for NHK radio. From the 1960s, he entered a Japanese trade company that traded with Russia. Until 1975 he worked in Russia for long periods, leaving his wife and three surviving children behind in Japan.

Just Rewards

The Japanese life story of Sugihara Chiune would contain yet another unexpected development. In 1968, Sugihara’s past caught up with him. One of the Jewish refugees he had saved by issuing the transit visas—an Israeli civil servant—located him. In 1969, the Israeli Minister of Religion—another refugee saved by Sugihara’s visas—invited him to Israel and awarded him the Israeli Ministry of Religion Prize for his actions during the war.

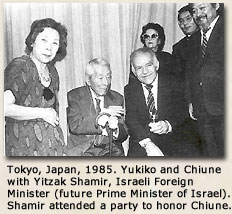

For the first time, Sugihara told Jewish survivors that he had acted despite directions from his home ministry not to issue transit visas. This information prompted additional efforts by the Israeli Minister of Religion to honor Sugihara by giving him the prestigious title of “Righteous Among Nations,” issued by the Yad Vashem Institute [6] on behalf of the State of Israel for non-Jews who risked their lives to save Jews from extermination. Sixteen years passed before Sugihara was given this title. By then (1985) he was too ill to travel to accept the prize, and his family would travel in his place. A year later he passed away.

Sugihara Chiune: Characteristics of the Japanese Story

The commemorative narratives of Sugihara, told and retold in Japan, have the following characteristics.

Sugihara as the Tragic Hero

Typically the narrative of Sugihara’s life is divided into two main parts. The first consists of about 47 years (until 1947) and makes up the bulk of the narrative. The second part consists of Sugihara’s later years—from 1947 until his death—and occupies only a short section of the whole story.

The narrative is linear; it progresses along the timeline of the years he was alive. Yet it also tends to return to a particular theme throughout: After the war, Sugihara, who was no longer a civil servant, and who led an anonymous life, would be repaid for his good deeds. The Jews he rescued would become his rescuers, and he in turn would change from honorable rescuer to the rescued. He would be rewarded for his deeds, regain his pride and self-confidence, and gradually regain honor among the Japanese, who knew nothing about his actions.

This narrative makes Sugihara’s life story fit well into the traditional Japanese narrative framework of the tragic hero. It makes Sugihara look the good hero, one who abides by Japanese tradition and actually comes out the loser, a “man whose single-minded sincerity will not allow him to make the compromises that are so often needed for mundane success” (Morris 1975: xxi), a man whose “courage and nerve may propel him rapidly upwards, but he is wedded to the losing side and will ineluctably be cast down” (Ibid).

The commemorative narrative is abundant with such tragic elements: Sugihara is cut off from his father’s economic support because of his wish to pursue a different future than the one his father envisioned for him; he is dismissed by the Foreign Ministry after the war despite his achievements as a diplomat in the service of his country, despite his knowledge of Russian language and culture, and despite the life-saving deeds that later would come to light. His dismissal is said to be interpreted by Sugihara himself as resulting from his granting of the visas, since however generous the act, it was against his superiors’ policies. Thus, he leaves the Foreign Ministry feeling a loss of face. Resolving to forget the past [7] and start afresh, he does not lead an easy life. Losing his high social status, he moves from job to job, lacking the economic security or prestige he enjoyed as a civil servant. In short, Sugihara’s commemorative narrative portrays the tragic hero so loved in Japan.

Main Protagonists and Main Event – Sugihara, the Jews, and Yukiko in Lithuania

The commemorative story of Sugihara appropriates certain characters as its leading actors. First, of course, is Sugihara Chiune. He serves as the main character and plays the leading role as the party that issues the life-saving visas—the role of the rescuer. Playing an important yet secondary role are the Jewish refugees, who appear mostly helpless and passive. Sugihara’s wife, Yukiko, plays a critical supporting role as Sugihara’s helpmate, assisting him in crucial moments of decision and helping him to save the Jewish refugees. She encourages him, strengthening his spirit and massaging his ailing body. No less importantly, she refrains from distracting him from his work.

The main event, which the entire life story of Sugihara is assembled to highlight, is his act of issuing the life-saving transit visas to the Jewish refugees. Indeed, there are few other critical events in the story. As articulated in the previous section, his role in securing the purchase of the Manchurian railroad is described in some detail; likewise, the story touches on his various positions as diplomat, government official, and Russian specialist, at times even hinting that he worked as a spy. The narrative leaves no room for doubt, however, that the main event—the event for which Sugihara deserves to be recognized as a great man, and for which he should be remembered—is his act in Lithuania of saving Jewish refugees.

Lack of Broad Context

The Japanese commemorative narratives of Sugihara refer to a narrow context. For example, the events pertaining to the issuance of the transit visas take place solely in Europe. The narrative emphasizes the relationship between the misery of the Jewish refugees and the presence of the Nazis and their murderous policies. However, little information is provided concerning Sugihara’s actions as they related to the Japanese state, which he served as a diplomat. Aside from mentioning regulations for visa issuance, the narrative skips over Japanese polices regarding the Jews, for example, the so-called Fugu plan. The Fugu Plan is the code name of a scheme set in 1930s Japan, to settle Jewish refugees escaping from the Nazis in Europe, in Japanese territories on the Asian mainland, to Japan’s benefit. The plan was first proposed in 1934, culminating in a solid plan in 1938. The plan was named for a favored fish delicacy that could also be poisonous. In addition, Sugihara’s visa story most often finishes with the issuance of the transit visas. The narrative does not go clarify whether and how the Jewish refugees managed to cross Russia, or how they spent their time in Japan, the colonies, or elsewhere [8].

Commemorative accounts of Sugihara tend to ignore altogether the existence of other Japanese figures who are said to have helped with the 1940-1941 rescue operation. These include army colonel Yasue Norihiro, naval captain Inuzuka Koreshige, and doctor Kotsuji Setsuzo [9]. The three play no role in the accounts of Sugihara’s acts. While the role of the first two officers has been questioned in some historical accounts, all agree on Dr. Kotsuji’s contribution to the rescue operation, so his elimination from the Japanese record is salient [10].

Japanese accounts also ignore Sugihara’s first marriage. While in China and Manchukuo, Sugihara was married for eleven years (1924-1935) to a foreign national—a Russian woman—and converted to Russian Orthodoxy, even changing his name at one point to Sergei Pavelovich (Levine 1996: 66-74).

Repetition

Japanese commemorative accounts repeatedly highlight words such as pacifism and humanism that almost always carry positive connotations in Japan. Likewise, there are repeated efforts throughout the commemorative narrative to establish Sugihara as a great man. For instance:

1. Japanese accounts emphasize that Sugihara was born on January 1, 1900, at the dawn of a new century, and portray his birth on this date as symbolic. New beginnings are invested with sacredness in many cultures, Japan being no exception. Born on the first day of a new century, it is suggested, Sugihara was destined from birth to become a great man.

2. As Sugihara was born to a family of samurai descent, he is said to have been trained in samurai etiquette, which meant, among other things, that he would be inclined to help those in need without expecting any reward.

3. Sugihara’s grades in elementary school are used to emphasize his unusual talent to excel at foreign language studies, a talent he would polish in junior high school and at the Harbin School. As such we are also reminded that he chose to keep studying in junior high school and move on to a university at a time when not many young Japanese were doing so.

4. Japanese accounts portray Sugihara as a family man: a caring father who converses with his children; a kind husband who takes advice from his wife, in short, an unusual Japanese character. When he confronts the second major life-changing event in the narrative, he thus discusses the matter with Yukiko, who calms his fears that issuing the visas will affect not only his future but also the future of the family, telling him not to worry.

5. Finally, Japanese accounts repeatedly insist that Sugihara acted alone and that he issued the life-saving visas in defiance of his superiors’ orders. They also repeatedly maintain that Sugihara was fired from the Japanese Foreign Service for no reason but his disobedience in granting the Jewish refugees the transit visas.

Discussion

First Two Commemorative Components

In a fascinating article considering the commemorative practices pertaining to Yitzhak Rabin in Israel, Vinitzky-Saroussi (2002 p. 35) notes:

Commemorative narratives, particularly the ones of painful pasts, can be understood as consisting of three components: (1) the protagonist(s) being commemorated, (2) the event itself, and (3) the event’s context. …Mnemonic narratives are framed through the emphasis on or absence of one or more of the three components of the narrative. …The components adopted [eventually] affect the contours of the collective that is addressed. The stricter the adherence to only the first or second components of the narrative (often associated with the “hard core” facts), the larger the audience that can gather around it. In other words, the “thinner” the message . . . the larger the audience that can identify with it.

Looking at the Japanese chronicles of Sugihara, one indeed discerns a clear focus on the first two components of the narrative (protagonists and major events), treating the third component—context—as narrowly as possible.

In the late 1980s, when Sugihara’s memory agents (his family members, biographers, and other storytellers) presented his story on the public stage, they first had to confront Japanese ignorance of the events. They set out to present a story that would allow Japanese to see Sugihara as one of their honorable representatives. The broader the Japanese collective enthralled by the narrative, the better. Toward this end, the context of Sugihara’s story was abbreviated. “It is around the context that most…organized ‘amnesia’ has set in”, declared Vinitzky-Saroussi (2002 p. 37). The portrayals of Sugihara’s life confirm this judgment.

The assembled narrative was meant to carve a respectable place for Sugihara Chiune in the collective Japanese memory. For that to happen, he had to win admiration and to demonstrate Japaneseness. Any elements that might have dulled the luster of his memory had to be glossed over, at times even removed from his story.

Examples of this abound:

1. Sugihara is presented as a diplomat, a government official, and a teacher (after graduating the Harbin School, he is said to have been a teacher there), but his role as a soldier and his activities as an intelligence agent are slighted or ignored entirely. They are hidden in order not to complicate the story by suggesting various negative associations with World War II.

2. Commemorative narratives trace Sugihara’s spiritual disposition to his samurai roots, his family, his culture, and the events that shaped him while growing up in Japan—in short, his Japaneseness. Accounts disregard the fact that although he lived almost 19 years as a child and adolescent in Japan, he afterwards lived most of his years in foreign cultures, which he deeply cherished, and the experiences of these years may also have guided his decisions.

3. Japanese narratives disregard Sugihara’s first marriage. His second wife, Yukiko, who was the first to frame the narrative about Sugihara, could have had personal reasons to avoid referring to the first wife. Yet the fact that subsequent Japanese narrators have followed suit, not only in their accounts, but even in creating the memorial hall in Yaotsu, could well be attributed to the fact that such information might dilute Sugihara’s Japaneseness. Pointing out that he was married for eleven years to a foreign national, and that he had changed his name and his religion, could awaken old fears and suspicions about his loyalty [11]. Was Sugihara really loyal to Japan, or did he “switch sides” while studying the Russian culture and language that he loved so much? Commemorative accounts avoid such questions by making no mention of his first wife. [12]

4. Finally, commemorative accounts of Sugihara insist that he was fired because of his benevolent act, while ignoring data suggesting other possible reasons. For this end the accounts highlight his samurai upbringing to stress his Japanessness, yet they disregard, for example, his problematic status as a non-career diplomat, a fact which may have simply placed him at a disadvantage during postwar reorganization of the ministry. [13]

The Dubious Success of Commemorative Efforts

The Japanese commemorative narrative of Sugihara Chiune provides a portrait of outstanding ethical conduct. In the midst of World War II, at a time when many lives were being viciously sacrificed, Sugihara made a courageous decision to save lives. This is exactly the kind of conduct likely to be respected in a postwar Japan with strong pacifist and humanist inclinations.

World War II memories in contemporary Japan, far from being a unifying factor, have been the source of deep conflict. This is exemplified by the repeated pattern of official apology and denial. In this light, Sugihara’s emergence as a national hero, a rare positive role model from the war epoch, can serve to unify deep divisions over war memory.

Yet the evidence is that most Japanese were ignorant of Sugihara’s story until the early 1990s, and even today the story is not well known. Why?

The Silence of the Japanese State

In the first place, the central government has always, for the most part, remained silent on the issues pertaining to Sugihara.

To be sure, government officials have attended commemorative events relating to Sugihara [14]. In the year 2000, an official plate was placed in the Foreign Ministry archive in Sugihara’s honor, and a commemorative postage stamp was issued in his memory. Yet Sugihara’s story is featured in very few authorized Japanese history or social studies textbooks. The supplementary educational materials that were prepared by Yaotsu to be taught in history and social studies classes, for instance, have not been used outside of schools in Yaotsu and a few other schools in Gifu.

Frustrated Efforts in Yaotsu

While the Japanese state center avoids commemorating Sugihara’s story, the town of Yaotsu—Sugihara’s hometown—continues to hail its hero.

Representatives of Yaotsu note that commemorating Sugihara poses a great challenge. “Back in the early 1990s, there were stories in the media about Sugihara and the Jewish refugees he helped to save”, one town official told me. “So we thought it was a good idea to set up a memorial site, as he was born here.”

Between 1987 and 1989, when Takeshita was prime minister, the government came up with a project called Furusato Sosei Kikin to rejuvenate Japan’s peripheries by giving each prefectural and municipal government the sum of 100 million yen (about US$800,000) to carry out projects to advance the interest of their localities. To receive the money, localities had to set up projects for which they would receive tax refunds. The initiative brought about a surge in local projects, in which many localities built up tourist areas (such as onsen, or hot springs), while some created programs by which the central government money would reach the local population, in the form of presents for newly born babies and so forth. The leaders of Yaotsu viewed the discovery of Sugihara’s story around that time as a windfall.

This was around the time when Oskar Schindler—the German national who saved many Jews during the war—reemerged on the international stage. Schindler’s story had drawn attention as early as 1982, when Thomas Keneally’s Schindler’s Ark drew acclaim, first in Britain, where it won the Booker Prize [15]. A Japanese translation of the book reached Japanese bookshops in January 1989.

Schindler most likely awakened the story of Sugihara in Japan. Sugihara’s family, and his wife in particular, realized that Sugihara’s life story contained similar elements of heroic rescue of Jewish refugees—heroism in the midst of a cruel war, which might touch the hearts of many Japanese. And so the story went public in the media, making Japanese proud that they had a Schindler of their own.

Aware of Schindler’s appeal worldwide, the Yaotsu town officials set out to promote the “Japanese Schindler” by building their Furusato Sosei Kikin project around Sugihara [16].

The goals of setting up a memorial site and propagating the story of Sugihara’s life blended with aspirations to craft a unique identity for the locality. As a small, rural town, Yaotsu’s population (fewer than 15,000 people) included a large number of aging members and faced such problems as relatively inconvenient access to neighboring districts. Town officials sought to “rejuvenate” the town and make it attractive to visitors and youth [17]. They hoped that Sugihara’s story would attract visitors; tourism would grow; town revenues would swell; and the town would prosper and attract a younger population.

But viewing the record of visitors to the memorial hall in Yaotsu since its opening in 2000, which was generously shared with me by the town office, I realized that after all few people have visited. During the three months of the Japanese winter, the monthly average is about 500 people, while in other months of the year the number climbs to an average of 2,000 people a month. Visitors to the memorial hall are asked to pay 300 yen (US$2.50) as an entrance fee. Thus, the monthly income from entrance fees varies from about 150,000 yen (US$1,260) to 600,000 yen (US$5,050), hardly enough to covers maintenance costs.

Two conversations I had with people in Yaotsu reflected the fact that the memorial has not generated significant interest or revenue.

A bus driver who drives regularly on the route between the center of Yaotsu and the Hill of Humanity told me that “Actually, not too many people visit the place. Most visitors are young children brought in by their teachers, but this also does not happen much. Though summer is considered the high season for visitors here, most of the year the buses go more than half empty”.

A conversation with a town official in Yaotsu in early 2007 yielded the following statement: “We would have liked to see more people—Japanese or foreigners—coming over to see the memorial for Sugihara. We even contacted JTB [Japan Travel Bureau, the national travel agency] and tried to look for ways to sell tour packages to this place or arrange yearly school excursions, but nothing has really materialized. Getting into town is quite difficult.” The official continued, “The only train stops in a nearby town, from which one has to take a bus in order to get here. Once in town, in order to reach the Hill of Humanity, unless one wants to walk for an hour or so, one has to take another bus, so it is quite inconvenient in terms of transportation. As a matter of fact, we are not prepared to welcome group tourism like school excursions . . . such excursions would mean that the town would have to supply beds and meals for hundreds of school children at one time. We are not prepared for that. There are no such facilities in town [18]”.

Thus commemorative efforts stall. Having taken on the Sugihara commemorative project ignored by the Japanese center, peripheral Yaotsu struggles to realize its potential. Being rural, remote, and bereft of facilities, Yaotsu has been unable to bring it to the attention of significant numbers of Japanese and foreign visitors.

Complicated Relations Between the Sugiharas and Yaotsu

Conducting research in Japan between 2005 and 2007, I often noticed that Japanese seem perplexed when I tell them that my research centers on “the commemoration of Sugihara Chiune in Japan.” Never have I sensed that my counterpart instantly knows who I am talking about, even among scholars. In many cases I have had to use the catchphrase “the Japanese Schindler” to prompt understanding. It appears that, after almost 15 years of efforts to place Sugihara Chiune in the Japanese collective memory, his actions are still far from widely known, and Japanese still find it hard to relate to and remember him.

In 1995 Sugihara’s wife, Yukiko, and their elder son, Hiroki, initiated a new commemorative project, this time in the United States. They lectured on Sugihara Chiune in Jewish communities there, collected funds, and in 1997 created the Visas for Life Foundation in California [http://visasforlife.org]. While Yukiko eventually returned to Japan, Hiroki decided to stay and manage the new memorial project. In fact, he stayed in the U.S. until a few days before he died of cancer in 2001. It appears that the Sugihara legacy found its strongest resonance in the United States, the country that has been most absorbed by the Holocaust, as indicated by the presence in Washington D.C. of the Holocaust Museum and by the critical role that the US played in pressuring Germany to provide reparations to the Jews and other victims of Nazism, and the US-Israel relationship.

As to my inquiry regarding of the role of the Sugihara family in the memorial project at Yaotsu, I was told that there is minimal cooperation. “Yukiko was invited to lecture at the site or was invited to ceremonies held there, but it seems as if the Yaotsu town office is avoiding unneeded cooperation with the family,” one informant told me. Another suggested that the town office was unhappy about the family going to the U.S. to collect money. “There are rumors”, added my informant, “that the family, especially the elder son, Hiroki, collected money promising to direct it to the memorial of his father, but instead he disappeared with the money.” [19]

A Problematic Narrative

Clearly, the commemoration of Sugihara has not captured the national imagination in Japan despite being one of the most positive war narratives for a country that continues to face great difficulty in commemorating that epoch. Except in Yaotsu, there are no squares, neighborhoods, and streets anywhere in Japan named after Sugihara. There are no national memorial ceremonies or even references by Japanese politicians to his acts. Sugihara’s commemoration is confined in time and space, and few Japanese remember him and honor the past he represents.

The Price of a Prize from Israel

The Sugihara story, as it has been assembled and propagated in Japan, does not provide the Japanese state space to express itself and use the story for its own interests.

The Japanese version of events was put forth first in Japan by Sugihara’s widow in the early 1990s. By then, Sugihara was already dead and had received the most prestigious prize the State of Israel could bestow—the title of “Righteous Among Nations”. As Sugihara had been a diplomat in the employ of his country, in order to receive that prize, he had had to be judged as acting on his own impulses and not on any policy formulated by the government, that is, at risk to his career and even his life. Sugihara made this clear when he first told some of the survivors, upon visiting Israel in 1969, that he had acted in spite of orders not to issue any transit visa to the refugees. Checking this version of events 15 years later, the Yad Vashem Institute decided that Sugihara indeed deserved the title and accorded it to him. Sugihara is the only Japanese to have been accorded such a title, thus placing him in the ranks of international figures such as Oskar Schindler.

Yet the prize also weighed heavily on the presentation of Sugihara’s acts, on the crafting of his memory. All of a sudden it became necessary not to disrupt the achievement associated with the prize, to keep the order of things intact, unquestioned. Assembling her recollections, after Sugihara’s death, insisting that Sugihara acted alone, Yukiko Sugihara, the widow, did just that. And her insistence on that version of events, made it even harder for other Japanese to question the story or present alternative versions. The Japanese state itself could not argue against this version by, for instance, stating in public that it had in fact maintained a policy of rescuing Jewish refugees and that Sugihara had known and acted in line with that policy (the Fugu plan) without besmirching Japan’s and Sugihara’s reputation.

Nevertheless, over the years a few dissident stories have cropped up, pointing at the existence of Japanese plans to save Jewish refugees and questioning the claim that Sugihara acted alone [20]. Yet on the whole, the title of “Righteous Among Nations” compels most Japanese scholars and commentators to support the version of Sugihara’s story that enabled him to earn the prize. The problem, however, is that this version of events is not usable in a national context, at least not as an official celebration.

The Sugihara story in Japan indeed features positive elements of humanistic behavior, but these are inseparable from the fact that Sugihara disobeyed state regulations. For the Japanese state this presents a problem of the lesson to be taken by future generations. Propagating Sugihara’s memory risks eroding state authority.

The Role of International Relations

By saving Jewish refugees during the war, Sugihara Chiune unknowingly tied his fate with the political entity the Jewish refugees would create after the war—that is, with the state of Israel. The story of his life demonstrates this connection, in that it was Israel that first honored him in the late 1960s. Yet while diplomatic relations between Japan and Israel have existed since the late 1940s, the Arab-Israeli conflict has rendered those relations somewhat tenuous in postwar Japan. Especially since the oil embargos of the early 1970s, relations with Israel have been kept as quiet as possible. From the point of view of the Japanese state, then, the Sugihara narrative poses another set of problems associated with Japan’s Middle East policy in general, its relations with Israel in particular. Actively propagating Sugihara’s story could potentially mark Japan as too friendly to Israel in Arab eyes, thereby jeopardizing Japan’s oil lifeline to the Middle East.

Meanwhile, as far as the central Japanese state is concerned, I believe that whatever nods have been made to Sugihara have in fact come in reaction to international pressure. The state of Israel had honored Sugihara (1969, 1985 [21])—and had done this while he was alive—and Lithuania also commemorated Sugihara’s memory, by naming a street in Kaunas after him (1991) and taking steps to turn the former Japanese consulate building, where Sugihara had issued his visas, into a memorial space. Thus, pressure gradually mounted on Japan to take steps to recognize Sugihara. Clearly, the modest recognition of Sugihara by the Japanese state has been a way of relieving that pressure.

A Tale That Slips From Memory

Finally, there is the problem of cognitive labeling. It is ultimately unclear how to place the narrative of Sugihara among well-publicized chapters of Japan’s past. Japanese narrative conventions relating to World War II most often consist of binary dispositions—with victims on the one hand, and aggressors on the other—and war stories most often involve Japan and Japanese playing one of these two roles.

The narrative of Sugihara deviates from this pattern. Victims are present, but they are Jewish, and while their savior is Japanese, there is at best only a tenuous and ambiguous connection between Sugihara and the Japanese state. In other words, the Sugihara narrative is problematic on a national and international scale.

Nietzsche once wrote (1989; p.61) that “if something is to stay in the memory it must be burned in: only that which never ceases to hurt stays in the memory”. In this light, the story of Sugihara is not destined to stay long in Japanese memory. The main victims are Jews, not Japanese, and the memory of Sugihara’s time does not hurt in the Japanese mind as it hurts in the Jewish mind.

Eldad Nakar (Ph.D.) recently completed field research in Japan about Sugihara while holding a visiting scholar position at Keio University in Tokyo. He is a sociologist by training, specializing in Japanese society and culture, and previously has published articles about Japanese Manga and Japanese visual culture. He has taught at Tsukuba University, Japan, at the East Asian department of the Hebrew University and at the Haifa University in Israel, and is presently an independent scholar.

He is the author of “Framing Manga: On Narratives of the Second World War in Japanese Manga, 1957-1977,” in: Mark W. MacWilliams ed., Japanese Visual Culture: Explorations in the World of Manga and Anime, M.E. Sharpe publication, (forthcoming, February 2008).

Posted at Japan Focus on January 21, 2008.

Notes

1. An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 5th MESEA Conference in Pamplona, Spain, in May 2006. I thank the JSPS for a grant making possible the research upon which this paper is based.

2. The date of Sugihara’s death, around the first week of August each year, was singled out as Sugihara Week, and short-essay and poem contests about Sugihara were held for children in the region.

3. The park was opened to the public in 1992. It was completed in 1995. The monument was erected sometime in 1996, and the Memorial Hall opened its gates in the year 2000.

4. The first television drama appeared in the mid-1990s and was called Inochi no biza (Visas for life). It was based on Yukiko’s first book. The famous Japanese actor Kato Go played the role of Sugihara. In October 2005, a two-hour drama filmed in Lithuania was broadcast on Fuji Television. The drama was called Nihon no Schindler, Sugihara Chiune monogatari—Rokusen nin no inochi no biza (The story of Sugihara Chiune, the Japanese Schindler: Visas for the lives of 6,000 people).

5. Haruki died from cancer at the age of seven, soon after the family returned to Japan.

6. Yad Vashem is Israel’s national memorial to the Jewish victims of the Holocaust. It consists of a memorial chamber, a historical museum, and other facilities created to commemorate the victims.

7. Sugihara Chiune, for most of his life, did not speak about his past in public. He left some notes that he wrote in the late 1960s, as a response to an inquiry by a Polish professor about his relations with the Polish underground. Yukiko writes in her memoir about some other notes that Sugihara left, but it is unclear exactly when he wrote them. Speaking to his relatives who still live in Yaotsu, I learned that he never spoke of his actions during the war and that they did not know of his deeds even at the time he was being awarded prizes from Israel. It was only after his death, when stories were appearing in the media, that they themselves learned of his actions.

8. Japanese chronicles typically emphasize exclusively the actions of Sugihara and provide little detail regarding the Jews he saved. I know of only one Japanese publication that differs: Yakusoku no kuni e no nagai tabi (A long journey to the Promised Land), written by Shino Teruhisa published in 1988. This was the first full volume on the issue in Japan. Western chronicles fill the gap, and offer a look at the matter from the point of view of the Jewish refugees. Such works probe how the refugees moved from place to place, how they lived, and how various political entities (Lithuania, Russia, Holland, and Japan) assisted in their escape. For the Fugu plan, see Hillel Levine 1996: 97-103; 270-1, and also Marvin Tokayer and Mary Swartz 2004 (1979). See also Dina, Porat. “Nessibot Vesibot Lematan Visot Ma’avar Sovyetiyot Leplitei Polin” (in Hebrew) (Conditions and reasons for the granting of Soviet transit visas to refugees from Poland), Shvut 6 (1979): 54-67; David Kranzler, “Japanese Policy Toward the Jews 1938-1941”, The Japan Interpreter, XI:4, spring 1977, pp. 493-527; Ewa Palasz-Rutkowska and Andrezej T. Romer, “Polish-Japanese Co-operation during World War II”, Japan Forum, Vol. 7, No. 2, autumn, 1995; Pamela Shatzkes, “Kobe: A Japanese Haven for Jewish Refugees, 1940-1941”, Japan Forum, Vol. 3, No. 2, October, 1991.

9. The Dutch Consul to Lithuania at the time, Jan Zwartendijk, reportedly gave Jewish refugees transit visas to a Dutch territory, the Dutch West Indies (Curacao), and on which enabled Sugihara to grant his transit visas. He, too, is often mentioned briefly, sometimes omitted all together in Japanese accounts.

10. For accounts that include the actions of these individuals, see Akira, Ito. 2002. The Path to Freedom—Japanese Help for Jewish Refugees. Tokyo: Japan Travel Bureau; Masanori, Tabata. 1994. “Mystery Behind the Myth”, Japan Times Weekly (December 17: 6-11); Pamela, Shatzkes. 1991. “Kobe: A Japanese Haven for Jewish Refugees, 1940-1941”, Japan Forum, Vol. 3, No. 2, October: 257-273; David, Kranzler. 1977. “Japanese Policy Toward the Jews 1938-1941”, The Japan Interpreter, XI:4, Spring: 493-527. A vocal speaker on behalf of the actions of the Dutch Consul, Jan Zwartendijk, is Heppner G. Ernest. See Jerusalem Post, June 21, 1995, “Japanese Granted, Dutchman denied Laurels for Saving Jews”.

11. For testimonies on such rumors and suspicions, see Levine 1996: 61-64; 101-3.

12. Espionage by individuals pretending to be nationals of a certain country while spying for a second or a third country is not a far-fetched story. The Richard Sorge affair, from exactly the time Sugihara himself was on active duty, in which a German journalist in Tokyo was found to have spied for the Soviet Union is a well known example. Deeply immersed in Japanese and German cultures, having love affairs with German and Japanese women, Sorge too was suspected at times by the Russians of being a double agent.

13. The fact that Sugihara remained in the Foreign Service for five years after the visa incident, and continued to serve in other locations in Europe, suggests that the visa issuance was not necessarily the sole, or even primary, cause of his postwar dismissal. Under Allied occupation, the Japanese Foreign Service was downsizing and hundreds of employees were dismissed. Sugihara might well have been dismissed as part of these reconstruction measures. As a non-career diplomat: a Foreign Service employee who had entered the service without going through the regular state examination for those planning to become civil servants, he was particularly vulnerable. On the distinction between career and non-career diplomats in the Japanese Foreign Service and the implications for their advancement, see Seishiro, Sugihara. 2001. Chiune Sugihara and Japan’s Foreign Ministry—Between Incompetence and Culpability Part 2, Preface vii – xlvii, and Hiromu, Kobayashi. 2004. Watashi (non kyaria) to kyaria ga gaimusho wo kusarasemashita (Non-Career and Career have corrupted the Foreign Ministry).

14. Prime Minister Takeshita Noboru attended the ceremony when Yaotsu unveiled its first Sugihara memorial in 1992. Also, when the Memorial Hall in Yaotsu was opened in 2000, Foreign Minister Kono Yohei attended the ceremony and even issued an apology for the misunderstanding of Sugihara’s past actions. As for that apology, Watanabe Katsumasa explains that it came merely to lay to rest the suspicion that Sugihara had illegally accepted money in exchange for issuing the transit visas to Jewish refugees, money that ended up in Swiss banks (Watanabe [a] 2001: 150-155; Watanabe [b] 2001: 3).

15. The book soon drew attention in the United States as Schindler’s List. Steven Spielberg created his acclaimed film Schindler’s List a decade later based on Keneally’s book.

16. From the data I was given by the Yaotsu officials, 82,700,000 yen from the Furusato Sosei Kikin fund was allocated to building the Sugihara Memorial Hall.

17. “Japanese domestic tourism, recreational travel by Japanese within the home islands, is a huge industry and one of the primary recreational activities undertaken by Japanese in all walks of life” (Peter, Siegenthaler 1999: 178). Looking at Japanese domestic tourism, Siegenthaler shows how Japanese localities “market” themselves as desirable tourist destinations.

18. There is no hotel in town. The only place that offers accommodation is a small minshuku—a Japanese-style boardinghouse. Otherwise, visitors stay in the nearby city of Kani.

19. My search for stories on this matter in the Japanese press has so far yielded only a short reference to a story published in an unnamed magazine in summer 1994, in which Sugihara Hiroki was reportedly said to have “misappropriated funds of the Sugihara Memorial Foundation and spent the donated moneys at Tokyo hostess bars” (The Japan Times Weekly, December 17, 1994, p.7).

20. One such dissident story was generated by Masanori Tabata in The Japan Times Weekly, 1994.

21. In addition to the awards mentioned already, a grove of trees was planted and named after Sugihara.

Works Cited and Consulted

Asahi Shimbun, 1968. “Yudaya nanmin yonsen nin no onjin” (The 4,000 Jewish Refugees Patrons). August 2.

FitzGerald, Frances. 1979. America Revised: History Schoolbooks in the Twentieth Century. New York: Vintage Books.

Ito, Akira. 2002. The Path to Freedom—Japanese Help for Jewish Refugees. Tokyo: Japan Travel Bureau.

Jerusalem Post, 1995. “Japanese Granted, Dutchman Denied Laurels for Saving Jews”. June 21.

Kobayashi, Hiromu. 2004. Watashi (non kyaria) to kyaria ga gaimusho wo kusarasemashita (Non-Career and the Career have corrupted the Foreign Ministry). Tokyo: Kodansha.

Kranzler, David. 1977. “Japanese Policy Toward the Jews 1938-1941”. The Japan Interpreter, XI/4, Spring: 493-527.

Levine, Hillel. 1996. In Search of Sugihara—The Elusive Japanese Diplomat Who Risked His Life to Rescue 10,000 Jews from the Holocaust. New York: The Free Press.

Morris, Ivan. 1975. The Nobility of Failure—Tragic Heroes in the History of Japan. England: Secker and Warburg Limited.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. 1989. On the Genealogy of Morals, trans. Walter Kaufmann. New York: Vintage Books.

Okamoto, Fumiyoshi. 2005. Ai no Ketsudan—Yaotsu-cho shusshin no gaikÅkan, Sugihara Chiune (Decision of Love—Sugihara Chiune, A diplomat who was born in Yaotsu Town). Gifu-ken Yaotsu-cho: Chubu Insatsu.

Palasz-Rutkowska, Ewa and Andrzej, T. Romer. 1995. “Polish-Japanese Co-operation During World War II”. Japan Forum, Vol. 7, No.2, Autumn: 285-316.

Porat, Dina. 1979. “Nessibot Vesibot Lematan Visot Ma’avar Sovyetiyot Liplitei Polin” (in Hebrew) (Conditions and Reasons for the Granting of Soviet Transit Visas to Refugees from Poland). Shvut 6: 54-67.

Shatzkes, Pamela. 1991. “Kobe: A Japanese Haven for Jewish Refugees, 1940-1941”. Japan Forum, Vol. 3, No. 2, October: 257-273.

Siegenthaler, Peter. 1999. “Japanese Domestic Tourism and the Search for National Identity”. The CHUK Journal of Humanities Vol. 3 (1999 Jan).

Sugihara, Seishiro. 2001. Chiune Sugihara and Japan’s Foreign Ministry—Between Incompetence and Capability Part 2. New York: University Press of America.

Sugihara, Yukiko. 1990. Rokusen nin no inochi no biza (Visas for the lives of 6,000 people). Tokyo: Asahi Sonorama

Sugihara, Yukiko and Hiroki Sugihara. 1995. Sugihara Chiune monogatari—inochi no biza arigatÅ (Sugihara Chiune: Thank you for the visas that saved lives). Tokyo: Kinnohoshisha.

Tabata, Masanori. 1994. “Mystery Behind the Myth”. Japan Times Weekly (December 17:6-11).

Teruhisa, Shino. 1988. Yakusoku no kuni e no nagai tabi (The long journey to the Promised Land). Tokyo: Riburio Shuppan.

Tokayer, Marvin and Mary Swartz. 2004 (1979). The Fugu Plan. Jerusalem: Gefen Publishing House.

Vinitzky–Seroussi, Vered. 2002. “Commemorating a Difficult Past: Yitzhak Rabin’s Memorials”. American Sociological Review, 2002, Vol. 67 (February: 30-51).

Watanabe, Katsumasa. 1996. Ketsudan—inochi no biza (A decision—visas to save lives). Tokyo: Taisho Shuppan.

—. 2000. ShinsÅ Sugihara biza (The truth—Sugihara’s visas). Tokyo:

Taisho Shuppan.

—. [a] 2001. Sugihara Chiune—rokusen-nin no inochi o skutta gaikÅkan

(Sugihara Chiune: The diplomat who saved 6,000 people). Tokyo:

Shogakukan.

—. [b] 2001. “Sugihara Chiune to miyako no seihoku” (Sugihara Chiune

and “miyako no seihoku” [words from the Hymn of Waseda University, literally meaning “the capitals of the north west”]). Waseda Kogiroku. Tokyo: Waseda University Press.