Eika Tai

Article Summary

Korean ethnic education in Japanese public schools, which started in the 1960s, is a form of multicultural education that provides useful ideas for multiculturalist teachers dealing with children of newcomer foreigners. In Osaka, Japanese and Korean activists with different political agendas developed two distinctive approaches. Those interested in the homeland politics of the two Koreas tried to develop an ethno-national identity among Korean children, while those involved in civil rights politics in Japan encouraged the development of political subjectivity.

Introduction

Multiculturalism has spread worldwide as managing cultural and ethnic diversity has become a key to political stability in many countries. While “multiculturalism in its diverse modalities has indeed become the official policy designed to solve racism and ethnic conflicts in the North,”[1] it has also been adopted in various ways in regions beyond the North, such as Asia, Africa and South America.[2] Japan has been part of this international wave of multiculturalism. The recent increase of foreigners in Japan (up to about two million) has contributed to spreading this idea in a society that has been dominated by the ideology of monoethnicity.

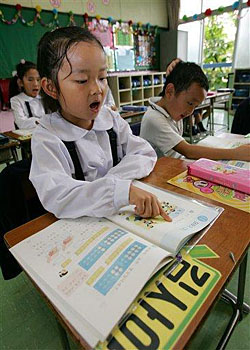

Educators concerned about children of newcomer foreigners have especially appreciated the idea. In the mid-1980s, scholars of education began to pay attention to the idea of multicultural education that was gaining popularity in other parts of the world. In the early 1990s, as the number of children who needed to learn Japanese as a second language noticeably increased, works on multicultural education were introduced from the United States, Canada, and Australia. By the late 1990s, teachers and researchers had attempted to apply these imported ideas to Japanese contexts. However, as Nakajima Tomoko, a leading scholar of multicultural education, points out, certain forms of multicultural education had been practiced long before multicultural education arrived from outside. One such form is Korean ethnic education. As early as the 1960s, Korean activists and Japanese teachers started to develop educational approaches tailored to the needs of Korean children enrolled in Japanese public schools. Nakajima points out that this educational movement coincided with the development of ethnic studies and multicultural education in the United States.[3]

Although the ethnic composition of resident foreigners has been diversified, the largest group of foreigners has remained Korean (598,687 in 2005). The majority of the Koreans are former colonial subjects and their offspring (447,805 in 2005). These resident Koreans have persistently demonstrated their political and cultural presence in Japan despite their disenfranchised status and the state’s assimilationist policies, through engaging in political activism and paying special attention to ethnic education. Their persistent presence in Japan is important not simply for their ethnic continuity. A constant reminder that Japan was once a multiethnic empire, it points to the need for a critical perspective in today’s multiethnic Japan. In light of the adoption by government and business organizations of a discourse of multiculturalism, it is imperative that multiculturalists learn from Koreans’ political struggles in order to steer multiculturalism away from the reproduction of the colonial hierarchy in today’s Japan, precisely the direction toward which those in positions of power seem to be heading with their interpretation of tabunka kyosei (multicultural co-living), a phrase used to define multiculturalism in Japan.

In what follows, I present a historical perspective on contemporary debates on multicultural education in Japan by examining its origins in Korean ethnic education.[4] In doing so, I want to join Nakajima to show how today’s multiculturalists can learn not only from studies of multiculturalism imported from outside but also from within, i.e., from the past experience of Korean ethnic education in Japan. Such a move has already been made to some extent by educators familiar with Korean ethnic education, as we will see. I also aim to contribute to comparative theory building in the field of multicultural education. Concerned about “the extent to which debates around multicultural/antiracist education have been hermetically sealed within national boundaries,” Stephen May has called for building a “cross-national perspective.”[5] Such an effort is important in order to prevent Western experience with multiculturalism from being “falsely” universalized.[6]

Debates on Multicultural Education in Japan

Let me first discuss contemporary debates on multicultural education in Japan, using a comparative perspective. In discussing “global constructions of multicultural education,” Carl Grant and Joy Lei identify three areas of concern: (1) the conceptualization and realization of difference and diversity; (2) the inclusion and exclusion of social groups in a definition of multicultural education; and (3) the effects of power on relations between groups.[7] In the first area, problems are found in the politics of difference played out by minorities, which tend to give rise to cultural essentialism, and in the practice of the tolerance of difference expected from majorities, which often ends with “boutique multiculturalism” characterized by superficial appreciation of ethnic cultures in such forms as foods and festivals.[8]

Similar debates are present in multicultural education in Japan. In their efforts to promote understanding of cultural difference, teachers often introduce food, fashion, and festivals from the homelands of newcomer children. This “three-F” approach is effective in raising self esteem among newcomer children and cultural awareness among Japanese children, when planned carefully. Yet, education centering on newcomers has been criticized for its tendency to concentrate on the three Fs, and to enumerate different cultures as if they were fossilized displays in a static museum.[9] In such educational practice, the majority Japanese, who are supposedly exercising tolerance, are observers of diverse cultures performed and displayed by foreigners. Moreover, there has been a critique of the superficial use of the catch phrase, “let’s turn difference into richness” (chigai o yutakasa ni), in multiculturalism programs, where newcomer children are often afraid of expressing difference despite efforts made by multiculturalists.[10]

The first area also concerns the dilemma of accommodating diversity within a nation state. In countries of immigration, such as the Unites States, Canada, and Australia, where the idea of a common civic culture is central to national unity, there has been a debate on the balance between the need to maintain a common culture and the need to recognize cultural pluralism. Multiculturalism is criticized as “inherently destabilizing and destructive of the common bounds of nationhood.”[11] Aware of such a critique coming from conservative and liberal commentators, multiculturalist educators stress the development of national identification based on a civic culture while appreciating different ethnic cultures.

In Japan, a country in which there has been little immigration since the Pacific War and in which citizenship is based on the principle of descent, the idea of a unifying civic culture is almost absent. The ethnic cultures of newcomer children are labeled as foreign, which deepens their separation from the majority students. Multiculturalist teachers in Japan emphasize, not national unity, but the idea of living together in harmony, kyosei, between Japanese and newcomers. Multicultural education may end up functioning to exclude newcomers as foreign and different and thereby solidify, not destabilize, Japanese national boundaries, while including the newcomers at the margins of society. As discussed below, the old practice of Korean ethnic education can offer a great deal to today’s teachers on the idea of kyosei.

In the second area, concerning the question of which groups to treat as multicultural, there is a difference between countries of immigration and those with descent-based citizenship. In the former, people seen as multicultural are nationals or future nationals. As in Germany, which has descent-based citizenship with some recent modification,[12] multicultural education in Japan focuses on foreign children. While also addressing issues surrounding the Ainu, and to some extent the Okinawans, “multicultural” tends to refer to the presence of culturally diverse foreigners in Japan, as demonstrated in multicultural education policies, which mostly include the term “foreigners” in their titles.[13] Naturalized children and Japanese children born of international marriage are treated as rutsu no ko (children with foreign roots), i.e., as foreign and different. While their difference is made visible, their Japaneseness or the changing content of Japaneseness is not addressed. Multiculturalism has emerged as a critique of the ideology of monoethnicity, but the myth of homogeneity among people within national boundaries is not effectively debunked, leaving the position of rutsu no ko suspended in relation to Japanese nation and ethnicity.

The third area is relevant to progressive critiques of multiculturalism. It has been argued that multicultural education fails to address adequately structural inequalities surrounding minority students. When preoccupied with superficial culturalism, it helps reconstitute the preexisting social hierarchy in a political economy of difference.[14] In countries with citizenship based on place of birth, this problem is addressed through the idea of minority rights. Multicultural education involving foreign children needs to deal with issues of rights differently; it needs to draw on international human rights laws, as in the case of multicultural education in Germany.[15] Moreover, in countries with a history of colonization, there has been a debate over continuity between the colonial past and contemporary representations of cultural difference.[16]

Preoccupied with helping newcomer children adapt to Japanese school environments, most multiculturalist educators in Japan slight issues of political economy and citizenship. While appreciating the imported idea, they do not realize that multicultural education in the United States, Canada, and Australia is primarily for nationals. It is true that concern with human rights is central to multicultural education policies, as Okano Kaori points out.[17] But such concern is rarely extended to socio-structural problems.[18] It has been pointed out that Japanese teachers do not have the same level of political consciousness toward newcomers as toward resident Koreans, who remind them of Japan’s responsibility for its colonization. Yet, the presence of newcomer foreigners in Japan, which is tied to Japan’s emerging neo-liberalism, is also continuous with its past colonialism. Korean ethnic education, which was directly connected to Koreans’ postcolonial struggles, can help politicize multicultural education in today’s Japan.

In sum, contemporary debates on multicultural education in Japan have similarities to and differences from multicultural education in other parts of the world. An examination of Korean ethnic education can help advance certain debates.

Two Approaches to Korean Ethnic Education

Ethnic education for Korean children has been provided mostly in two different types of schools: public schools under the control of the Japanese government and Korean ethnic schools operated by Korean organizations. The majority of Korean children have been enrolled in the former. I want to examine the rise and development of Korean ethnic education in public schools in Osaka Prefecture, home to the largest Korean population in Japan.

The ethnic education movement in Osaka Prefecture is not monolithic. The movement has been started, sustained, and expanded in varying social contexts by people with diverse political goals. Yet one can still recognize two major approaches in the movement, which roughly correspond to two political orientations in Korean ethnic activism: homeland politics centered on Korea and led by Chongryun (the General Association of Korean Residents in Japan) and Mindan (the Korean Residents Union in Japan) supporting North Korea and South Korea respectively; and a civil rights struggle in the context of Japan led by Mintoren (National Council for Combating Discrimination against Ethnic Peoples in Japan). The two approaches differ not only in the content of education but also in the interpretation of Koreans’ status in Japan, reflecting the political goals of those who developed the approaches.

The first approach, advocated by homeland-oriented activists, revolves around the maintenance and revitalization of ethnic culture in relation to Korea, while the second, favored by civil-rights oriented activists, focuses on anti-discrimination education and the development of political subjectivity. Activists and educators themselves comment on this distinction, calling the former an ethnic-culture approach and the latter an anti-discrimination approach. To be sure, neither the divide between the political orientations nor the line between the two approaches is absolute in actual social practices; many activists are interested in both types of politics and many teachers integrate the two approaches. Yet distinguishing the two approaches helps to clarify the nature and significance of the ethnic education movement.

In his ethnographic study of Korean ethnic classes in Osaka’s public schools, Jeffry Hester finds that both Korean and Japanese teachers see “an identification with a Korean heritage as key to a positive self-image.” He also notices a difference in emphasis between the two groups; the Koreans seek “to create, or at least plant the seeds of, a Korean national subjectivity,” while the Japanese stress “the goal of eliminating the stigma heretofore attached to the status of ‘Korean.’” [19] This tendency may be observed if the teachers are grouped nationally. However, the difference is more a function of the political orientations of the teachers than of their national backgrounds. As shown below, some Japanese teachers are concerned with the development of a Korean national subjectivity and some Koreans stress the goal of constructing a political subjectivity for fighting social stigma.

The Ethnic-culture Approach

The ethnic-culture approach was developed through an educational movement in and around Osaka City. It was rooted in Koreans’ struggle in the late 1940s to provide ethnic education (minzoku kyoiku) for Korean children. As soon as their homeland was liberated in 1945, Koreans who remained in Japan began creating schools to revitalize their culture suppressed under assimilationist policy and to raise national consciousness among Korean children. Some 550 schools were created within a year, accommodating 44,000 students. The League of Koreans, created in 1945 to protect the interests of Koreans in Japan, played a central role.[20] However, the Japanese government demanded in January 1948 that Korean schools comply with the School Education Law of 1947, which required that the language of instruction be Japanese in accredited schools. Korean would be taught only in extracurricular courses. The Koreans opposed this intervention and protested against the government’s move to close non-accredited Korean schools. In April 1948, tens of thousands of Koreans demonstrated throughout Japan, and many were arrested during the month-long turmoil. In Osaka, where 30,000 demonstrated, a Korean boy died from police fire. In 1949, the Japanese government ordered the dissolution of the League of Koreans and closed most of the 337 schools operated by it, deploying armed force.[21]

Korean children were transferred from ethnic private schools to Japanese public schools. After the 1948 protests, Koreans in Osaka Prefecture persuaded the governor to sign a memorandum that guaranteed the opening of ethnic classes (minzoku gakkyu) in 32 public schools and the hiring of 36 Korean ethnic instructors (minzoku koshi) for ethnic classes. In addition, Nishiimasato Junior High School of Osaka City, intended exclusively for Koreans, was opened in 1950. [22] After regaining independence in 1952, however, the Japanese government made the operation of ethnic classes difficult. It took the stance that it would admit Koreans, who were no longer Japanese nationals, in public schools only if they accepted the education prescribed for Japanese children by the Ministry of Education. Local schools followed the guideline of “treating Korean children in the same way as Japanese children” and taught them to “live like Japanese.”[23] School administrators and teachers routinely instructed Korean children to use Japanese-style names and to pass as Japanese, using the possibility of discrimination as their reason. The ethnic education movement in Osaka City rose as a challenge to this assimilationist practice.[24]

In the late 1950s, Chongryun began to open private schools that were partially funded by North Korea. By the early 1970s, it had established 180 schools of from primary school through university with about 35,000 students, about a quarter of school-age Koreans.[25] But relatively high tuition and limited school locations made it difficult for the majority of Korean parents to send their children to those schools. Political divisions within the Korean community and the desire by some to assure Japanese education for their children led others to choose the public schools. The 1965 South Korea–Japan Normalization Treaty guaranteed the right of Koreans to receive education in the public school system.[26] By then, there had been a decline of ethnic classes in Osaka, partly because of the 1961 transfer of Nishiimasato School, which supported those classes, into the Chongryun-led school system with an educational approach modeled on North Korean education.[27]

Korean activists and Japanese educators who launched the multicultural educational movement in Osaka City respected the assertion of the 1948 protests, namely, Koreans’ right to maintain the culture and identity of their homeland. The activists tried to maintain ethnic classes, which stressed the national culture of the homeland, and used those classes as a model for the ethnic classes they created. The city’s Korean community, the largest in Osaka Prefecture, also stressed a culture orientation toward ethnic education. Koreans began to settle in Osaka in the 1920s and by the 1940s many operated independent businesses or were employed as skilled workers.[28] In those districts with high concentrations of Koreans, including Ikaino where about a quarter of residents were Koreans, Korean culture was played out in everyday life. The city was also home to many Korean political organizations, including the major branches of Mindan and Chongryun, which fostered political debate about the divided homeland among Koreans. These factors contributed to the formation of the ethnic-culture approach, which focused on the concept of ethnic nation (minzoku) as understood in relation to the Korean homeland. However, it was ultimately the political orientation of people involved in the movement that shaped Korean ethnic education.

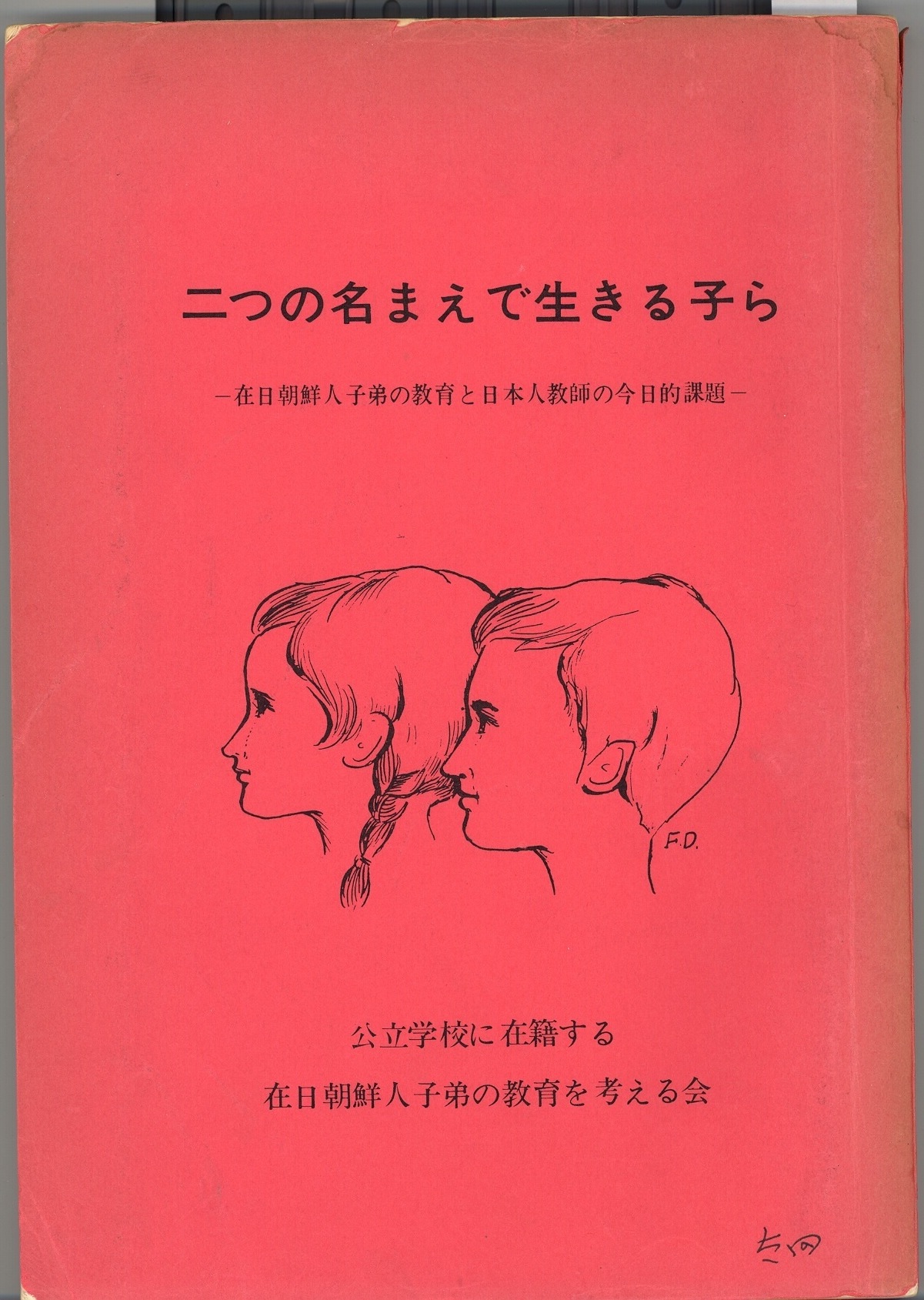

The ethnic-culture approach was developed through collaborative efforts of Japanese teachers and Korean activists. At early stages, the former took the initiative. Their educational activism was a response to the disinterest and discriminatory attitude of other Japanese teachers. The Osaka City Teachers’ Union became concerned about education for Korean children in the late 1950s, holding, for example, a workshop about these children’s ethnicity in 1957.[29] At the Union’s 1959 workshop, members recognized the needs of Korean ethnic education. However, the basic stance of the Union was that Japanese teachers could do nothing but encourage Korean children to attend Korean schools.[30] In 1965, as it became clear that most Korean children would remain in public schools, Osaka City established the Research Council for Foreign Children’s Educational Problems. Under the leadership of the Council, some schools began to look into interethnic conflicts. However, the Council came under severe criticism in 1971, when a public report based on input from the Council revealed its members’ discriminatory attitude toward Koreans. The Council members described Korean students as selfish, slovenly and defensive, and regarded their ethnic consciousness as a source of school disorder.[31]

This incident brought about the creation of the Club for Thinking about Education for Korean Children Enrolled in Public Schools (ZOK), an activist organization that has played an important role in the educational movement to this day.[32] ZOK was formed at a meeting in which about 1,000 people gathered to criticize the incident. ZOK members, consisting of school teachers, educational administrators, and researchers from Osaka City and neighboring cities, held meetings and workshops on education for Korean children, as well as on political problems such as immigration control and colonial history. They also took political action, holding political gatherings and lobbying municipal offices to improve the plight of Korean students. As a volunteer organization, ZOK worked closely with the Osaka City’s Teachers’ Union.

While members of ZOK had diverse opinions, they shared a few basic ideas. First, they ascribed problems surrounding Korean students to international politics, and held Japanese people, including themselves, responsible for the problems. Seeing the use of Japanese names prevalent among Korean children as a legacy of colonial assimilationist policy, they believed that they, as Japanese, should not allow the practice to continue.[33] They were also concerned about Japan’s postwar politics with regard to the two Koreas. Having protested against the 1965 South Korea-Japan Normalization Treaty over the failure to enter into treaty relations with North Korea, most ZOK members were aware of how international politics created problems for resident Koreans.[34] ZOK situated the issue of Korean ethnic education in the context of Japan–Korea political relations.

Second, ZOK regarded Korean students as Korean nationals in the Diaspora. ZOK members were concerned about the question of how to educate foreign nationals in the Japanese national school system.[35] As a ZOK member told me, other teachers treated Korean students the same as Japanese students, neglecting their difference in nationality. ZOK members thought it their duty to create a space in their schools where Japanese and Korean students could meet on an equal footing as different nationals. To this end, ZOK teachers helped Korean students to develop an ethno-national consciousness and taught Japanese students to support Koreans’ struggle. They also engaged in “teaching Korea correctly,” an expression they used as a political slogan, to eliminate the social stigma attached to Korean ethnicity. They regarded ethnically marked personal names as essential to national identification, and encouraged Korean students to use their true names. Believing that educators should take the initiative in treating Koreans as Korean, some schools made it a rule to call all Koreans by their true names.[36]

The third point is a corollary to the second; ZOK members wanted to distinguish education for Koreans from education for burakumin (former outcastes), who were Japanese nationals. Burakumin and Korean communities often stood side by side in poverty-stricken neighborhoods in Osaka, as both were marginalized economically and socially. At school, burakumin and Korean children had similar problems, missing many classes, coming to school with empty stomachs, and expressing frustration in delinquency. In trying to solve problems surrounding Korean students, many teachers drew on their experience with “liberation education” developed by burakumin activists. They encouraged Koreans to disclose their ethnicity and liberate themselves based on ethnic pride.[37] Yet, ZOK members did not equate Korean ethnic education with liberation education because they wanted to respect the idea of minzoku and did not want to reduce it to a matter of ethnic discrimination.

The event at Nagahashi Elementary School, located in a burakumin district of Nishinari Ward, where 20 per cent of residents were Korean, marked a breakthrough for ZOK. In 1972, Korean parents demanded that their children be enrolled in the school’s supplementary courses provided for burakumin children, accusing teachers of ignoring Korean children who also needed such extra help. After negotiating with the City Board of Education, Korean parents and Japanese activist teachers, including ZOK members, succeeded in establishing ethnic classes for Korean children, which were separate from supplementary courses for burakumin.[38] Although Osaka City soon withdrew promised assistance, extracurricular ethnic classes were maintained through collaboration between volunteer Korean instructors and Japanese activist teachers.[39] This case triggered the opening of volunteer-based ethnic classes elsewhere in the city and beyond. This was much needed in Osaka City, where in 1972, about 5 per cent of the children enrolled in grade schools were Koreans, and the enrolment rate was more than 20 per cent in a dozen schools, including one with more than 50 per cent.[40]

The creation of ethnic classes at Nagahashi Elementary School was greatly affected by homeland politics. The selection of Korean instructors was complicated by resident Koreans’ political divide. The presence of two Korean schools in Nishinari Ward, one supporting North Korea and the other South Korea, contributed to this complication. The two Koreas’ communiqué of 4 July 1972, which pointed toward their unification, eased the political tension to some extent, but the divide persisted. The Association for Scholarships for Koreans, which took a neutral position, was entrusted with the selection process and chose instructors from both North and South supporters. Still, Korean parents complained when their children were sent to an ethnic class with a Korean instructor siding with the government they opposed.[41] ZOK as a group decided to support the idea of Korean unification and tried to reconcile the political conflict in order to have the smooth operation of ethnic classes.[42] Thus, the nature of ethnic classes at Nagahashi Elementary School, which was to become the center of ethnic education in Osaka City, was homeland oriented.

Korean pupils at Nagahashi played an important role in the creation of ethnic classes. Having learned the importance of their mother tongue from Japanese teachers, they demanded the hiring of native Korean speakers for ethnic classes, chanting “We want our language back!”[43] Liberation education prepared them to take such political action.

Park Chung-hae, a graduate of a Korean college in Japan, became one of the first instructors at Nagahashi. She was eager to teach the culture of the homeland, such as Korean songs, games, folktales and language, and wanted her pupils to respect the idea of the unification of the two Koreas. As a child, she had experienced the 1948 closure of Korean schools and Koreans’ protests against this measure. She herself was forced to transfer to a Japanese school, where she was made to use a Japanese name. She decided to become a teacher because of this experience. At Nagahashi, she found it necessary to pay attention to the needs of Korean children growing up in poverty and facing discrimination. She taught them to cope with their predicament based on pride in their homeland and their newly learned cultural knowledge. She called her pupils by their Korean names and tried to develop national consciousness in those who had been culturally assimilated. Having them interview their grandparents and showing them the locations of their hometowns on a map of Korea, she stressed how they were connected to Koreans in the homeland culturally and genealogically. Ms. Park, who was to form and lead the association of Korean instructors, was influential in shaping the content of ethnic education in Osaka City.

While working with Japanese activists, Korean instructors began to take the initiative in organizing political actions themselves. Starting in the late 1970s, they demanded that Osaka Prefecture maintain memorandum-based ethnic classes, which had lost two thirds of the original instructors due to retirements and the lack of support. In 1984, Koreans formed Minsokkyo (the Association for Advancing Ethnic Education). Its activism was aimed at securing financial support from local administrations for the maintenance and expansion of ethnic education. In line with the principles of the 1948 protests, Minsokkyo contended that Korean children had the right to learn the ethnic culture of their homeland. Through signature-collecting campaigns and lobbying the Osaka Prefecture Board of Education, it succeeded in sustaining the memorandum-based ethnic classes that would otherwise have been closed. ZOK respected Minsokkyo’s political initiatives. With the creation of Minsokkyo, Japanese and Korean activists began a new round of collaboration squarely on an equal footing, as a ZOK member told me.

While including the association of Korean instructors in it, Minsokkyo kept a division between ethnic education itself and political activism, leaving Korean instructors and children in ethnic classes to focus on learning culture. Like ZOK teachers, Minsokkyo members did not want to reduce minzoku to politics.

In response to the educational activism led by Minsokkyo and ZOK, Osaka Prefecture established “the Basic Guideline of Education for Resident Foreigners” in 1988, making ethnic education an issue for all schools in the prefecture. In 1991, when a bilateral agreement between South Korea and Japan was signed, the Japanese Ministry of Education instructed prefectural boards of education to see to the smooth operation of ethnic classes. This contributed to the creation of the 1992 educational project for Koreans in Osaka City, which made volunteer-based ethnic classes official and provided financial resources. It helped to open more ethnic classes in the city, responding to renewed interest in ethnic classes among Korean parents sparked by the 1988 Seoul Olympics Games.

While the central government remained indifferent to ethnic education, Japanese teachers concerned about Korean students formed a nationwide network to promote ethnic education in their respective localities. ZOK initiated this networking by holding nationwide meetings at the end of the 1970s.[47] The meetings resulted in the formation of Zenchokyo (Nationwide Association for the Study of Resident Korean Education) in 1983. ZOK was subsumed under this umbrella association while keeping some independence from it. As Kishida Yumi suggests, in comparison to other Zenchokyo groups, ZOK paid more attention to Japan’s responsibility for colonial history and Korean children’s right to receive ethnic education. The others were primarily concerned about the development of healthy personalities free from the effects of ethnic discrimination. For them, the starting point of ethnic education was not minzoku (ethnicity) but ethnic discrimination.[48]

The Anti-discrimination Approach

The anti-discrimination approach was developed in two different locations in Osaka Prefecture: Takatsuki City and Yao City, where Korean populations were much smaller than in Osaka City. There, Japanese teachers also played an important role in educational activism, but they led their Korean students to take center stage. Appreciating the idea of liberation education, the Japanese teachers aspired to teach Korean students to develop political subjectivity and take the initiative in liberating themselves and changing discriminatory social institutions. Some Korean teenagers then began community-based educational activism, establishing their own activist groups, Mukuge Society in Takatsuki and Tokkabi Children’s Club in Yao. The two groups collaborated closely in the 1980s, forming the Osaka branch of Mintoren, an umbrella organization of locally based civil rights groups. The groups kept distant from Mindan and Chongryun, which denounced the civil rights movement as tantamount to assimilation. For Mukuge and Tokkabi activists, ethnic education was an integral part of their political struggle to eliminate ethnic discrimination in society. The following discussion focused on educational activism in Takatsuki City.

The anti-discrimination approach was originally formed in the educational movement of Rokuchu (the Sixth Junior High School) in Takatsuki City. Public schools in this city, with a concentration of low-income residents, took up the issues of human rights and anti-discrimination more seriously and earlier than elsewhere.[49] Rokuchu was opened in 1963 and many of its teachers were particularly active in addressing problems surrounding marginalized students, including Korean students. In the school district of Rokuchu, there was a small Korean enclave called Nariai inhabited by several dozen Korean families. This Korean community formed in the 1940s when forced laborers were brought from colonial Korea to the construction site of Tachiso, a secret military warehouse. Nariai was a small valley demarcated from Japanese residential areas in the surrounding hills, and its infrastructure remained poor long after improvements had been made elsewhere. Korean workers in Nariai mostly eked out a living as construction laborers.[50] The Rokuchu movement revolved around Korean students from Nariai as well as marginalized Japanese students.

At Rokuchu, many teachers enthusiastically sought to implement liberation education and “to re-engineer classroom relations so that children subject to discrimination would be at the center of activities rather than being banished to the periphery.”[51] The teachers dealt with various forms of discrimination: discrimination against Koreans, burakumin, the poor, people with disabilities and people with less-than-average intellectual competence. They cherished the idea of comradeship (nakama), which would unify people who were discriminated against with those willing to join them in fighting against discrimination. The goal was not creation of a harmonious community; rather, they sought to create something like what Sonia Nieto calls a “learning community,” where “all voices are respected” while struggle, conflict and real differences continue to exist.[52] Yoshioka Haruko, one of the teachers who led the Rokuchu movement, told me that she pushed her students to confront one another and express their frustration, anger and criticism. She dealt with those feelings not as personal problems, but as problems for the whole class and the whole school to tackle. Thus, she was practicing “multicultural education in a socio-political context,” i.e., critical pedagogy for social justice important for all students.[53]

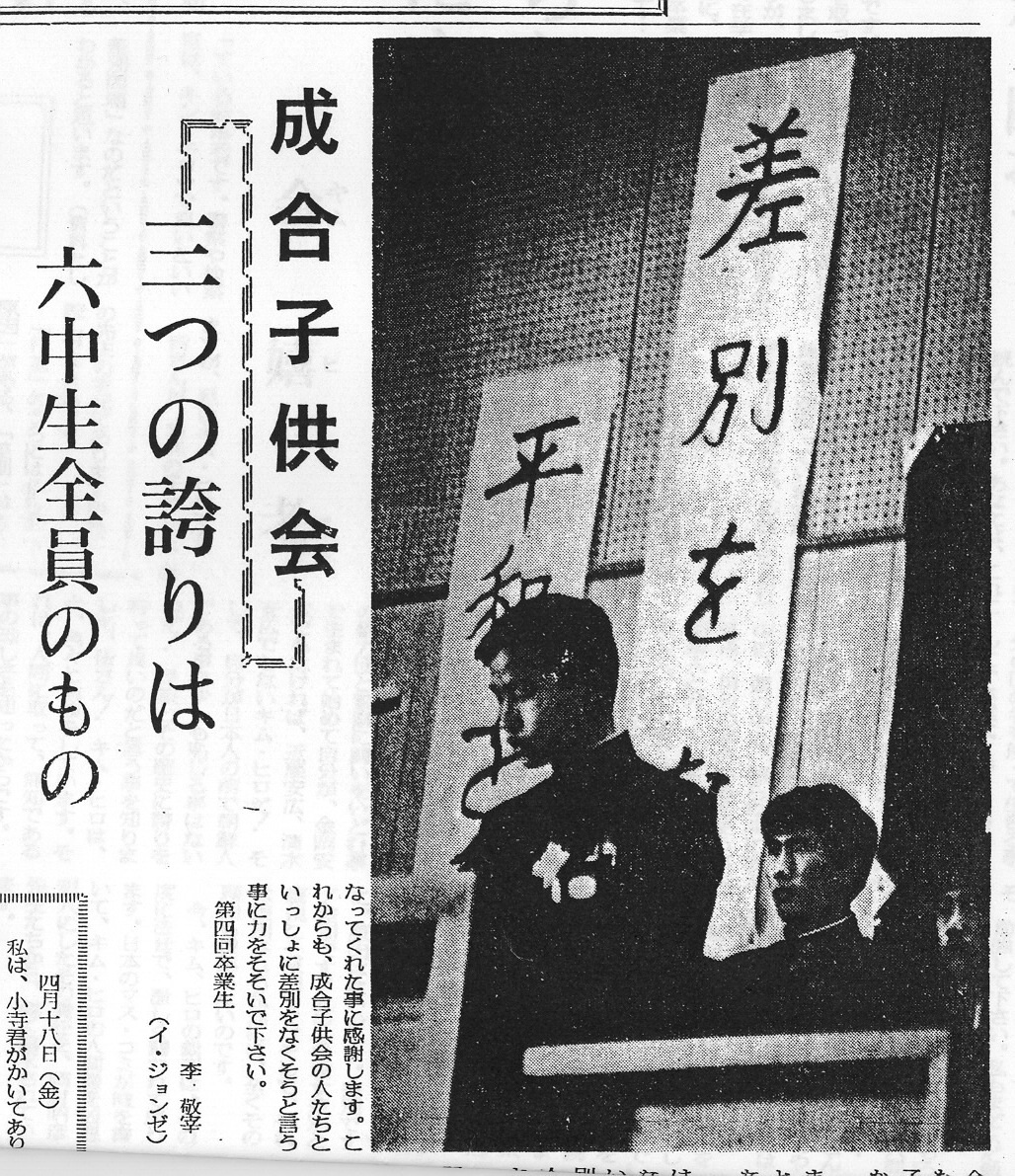

While facilitating the building of nakama, the teachers encouraged Korean students to “come out,” declare their ethnicity, and fight against discrimination, just as they did with burakumin students. Korean students at Rokuchu began to perform Chosenjin sengen (the declaration of being Korean) in their homeroom classes as early as 1964.[54] Among many events at Rokuchu, the 1969 graduation ceremony was particularly important. Twelve graduating Korean students decided to use their Korean names instead of the Japanese names they had been using to pass as Japanese. Reported in a nationwide magazine, their coming-out at the public ceremony had significant impact on young Koreans and Japanese educators.[55] As Ms. Yoshioka told me, the event was a form of political activism planned and led by students, who learned from their teachers how to take political action.

The Rokuchu teachers, feeling responsible for Japan’s colonization of Korea, paid particular attention to Korean students. In 1967, they created the Nariai Children’s Club, where Korean children could share their feelings about discrimination and learn about Korean history, culture and language. This club can be considered to be the first ethnic class ever created after the opening of memorandum-based classes, predating those at Nagahashi Elementary School. Children’s clubs were opened in other schools after 1972, when Takatsuki City, in response to educational activism, decided to hire two part-time instructors and made the status of children’s clubs official in the public school system.[56] The Japanese teachers tried to link children’s clubs to regular classes so that Japanese students would learn from Korean students’ struggles.[57]

In Takatsuki City, neither the expression minzoku gakkyu (ethnic class) nor minzoku koshi (ethnic instructors) was used; kodomo-kai (children’s club) and shidoin (mentor) were used instead, drawing attention away from the concept of minzoku and to the empowerment of children. As Ms. Yoshioka recalled, the teachers did not even think of the word minzoku until they heard about it from a journalist who visited Rokuchu. This does not mean that their political consciousness was narrowly focused on education. They were concerned about social problems of the time such as the Vietnam War and environmental pollution, and they taught their students to think about the problems critically. Just like ZOK members, they wanted to take responsibility for colonial history. Yet they understood it as a source of discrimination relevant to other forms of discrimination in contemporary society, instead of linking it to the subsequent history of Japan–Korea international politics.

The anti-discrimination approach was consolidated in Takatsuki’s public schools as Mukuge became influential. Yee Kyung-jae, who played the leading role in the 1969 Rokuchu graduation ceremony, concerned about the delinquent behavior of younger Koreans, launched Mukuge in 1972 to create a place “where Korean kids could get together and educate each other.”[58] Soon, he realized that his activism should be directed to the improvement of the local community and created a community-based children’s club in 1978 in Nariai, separate from the school-based children’s clubs. Working in a quarry during the day, he mentored younger Koreans and helped them with their school work in the evening. Denied support from Mindan and Chongryun, which directed attention to the homeland, not to life in Japan, he collaborated with other young activists in Takatsuki, both Korean and Japanese, to open children’s clubs in other locations in the city.[59]

Like his teachers, Mr. Yee did not use the term minzoku. Critical of the Korean nationalist ideology associated with that term, he avoided it. He used the socially stigmatized term “Chosenjin” (Korean), by which he meant the status of the oppressed. He was committed to “transforming that position into a positive, collective one.”[60] He thought his ethnic consciousness was low, but he started ethnic activism because of his resistance to social discrimination. At Mukuge, under his leadership, the use of a Korean name conveyed a “resistance identity,”[61] rather than a Korean ethno-national identity. Mukuge started cultural programs in 1982, but they were tied to political activism; Mukuge members played Korean music at festivals for the antinuclear movement and performed Korean dance in local festivals to assert Koreans’ political presence.[62]

Mukuge’s young activists lobbied the Takatsuki City Board of Education to seek financial support for their activities. Arguing that they were fighting social discrimination in the city, which honored the idea of human rights, they succeeded in getting annual budgets, albeit in small amounts.[63] They expanded educational activities for children and started literacy courses for elderly Koreans. In response to their activism, in 1982 the city created “the Basic Guideline of Education for Resident Foreigners of Takatsuki City”, long before other cities made similar guidelines. In conjunction with the guideline, the City Board of Education implemented “the Education Project for Resident Koreans” in 1985, assuming the financial responsibility for running Mukuge’s educational programs and hiring a few fulltime instructors. Under the project, those instructors worked for both school-based and community-based children’s clubs and consolidated their status in the public school system, as Mukuge hoped they would.[64] In this way, Mukuge assumed a central role in ethnic education in Takatsuki City.

To be sure, Japanese teachers continued to play an important role in the educational movement in the city. As Mukuge activists recognized, their negotiation with the city would not have been successful without support from Rokuchu’s teachers and the city’s Teachers’ Union.[65] Creating a special committee on education for Koreans in 1974, Kodokyo (Takatsuki City Association for the Study of Burakumin Education) tried to open more children’s clubs in schools, encouraged teachers to pay attention to the ethnic background of Korean children, and tackled job discrimination against Korean graduates.[66] In 1976, the City Board of Education started publishing a bi-annual magazine Chindarure to provide teaching materials and methods for ethnic education. Many Japanese teachers engaged enthusiastically in co-teaching children’s clubs with Korean instructors and “teaching Korea correctly.” As this expression suggests, many teachers in Takatsuki’s schools joined ZOK and learned from its activism.

Mukuge activists approached education for Korean children in connection with ethnic discrimination prevailing in various facets of everyday life, especially employment. They negotiated with the city and succeeded in 1979 in eliminating the nationality requirement from eligibility to take some public-sector jobs. This requirement was a major source of job discrimination against resident Koreans. In cooperation with another activist group, Mukuge also created in 1990 the Society for Preserving Tachiso (see above), and tried to keep alive the cruel history of forced laborers brought over to Nariai from colonial Korea.

As it joined Mintoren in the 1980s and began to work with Tokkabi, Mukuge expanded its civil-rights agenda, participating in the anti-fingerprinting movement and fighting the exclusion of Koreans from the National Pension. Fighting together in the civil-rights movement, Mukuge and Tokkabi activists closely collaborated for their educational programs, exchanging instructors for children’s clubs. They came to share the same goal, i.e., to create a society where Japanese and Koreans could “live together,” the key theme of Mintoren’s activism.

Mintoren’s approach was delineated in the 1992 booklet by Korean and Japanese educators working with Mukuge and Tokkabi.[67] The goal of education was to teach Korean children to live as zainichi, as people having ethnic roots in the Korean Peninsula and residing in Japan. Three objectives were identified to attain this goal: to develop ethnic consciousness and the awareness of oppressed status; to improve academic achievement at school; and to develop a will to fight ethnic discrimination and gain citizenship rights. Mintoren stressed the need for political activism to secure Korean graduates’ academic and career opportunities, criticizing culture-centered ethnic education that lacked this political perspective. Mintoren advocated the creation of group unity among Koreans as well as the idea of co-living (kyosei) between Koreans and Japanese. Japanese children were admitted to children’s clubs as long as they helped Koreans develop ethnic consciousness. Learning culture, such as Korean dance and music, was considered important not as an end in itself, but to develop ethnic pride and fight ethnic discrimination. Thus, Mintoren’s approach to ethnic education centered on anti-discrimination.

Orchestrating the civil rights movement energetically, Mintoren emerged in the 1980s as a strong alternative to Mindan, Chongryun, and other Korean organizations. Against this backdrop, Mukuge and Tokkabi presented their educational approach as distinct from Minsokkyo’s and ZOK’s. They selected their own instructors as shidoin for children’s clubs, taking exception to Minsokkyo’s practice of sending instructors to ethnic classes in Osaka Prefecture. Mukuge even accepted Japanese as shidoin if they were committed to fighting ethnic discrimination, and it differentiated itself from Minsokkyo, which hired only Korean instructors. Tokkabi, formulating its own method for dealing with Korean names, criticized ZOK teachers for “imposing” the use of Korean names on children who had yet to develop a political subjectivity.[68]

Thus, in Osaka Prefecture there was tension between the two camps: those advocating the anti-discrimination approach and those favoring the ethnic-culture approach. Individual teachers drew on both approaches. Yet, the tension between the two camps was intense, involving not only education but also political ideologies. The tension was most intense among Koreans who were sharply divided over politics. As for Japanese teachers, the tension was translated into an organizational conflict between ZOK and the mainstream Zenchokyo in the early 1990s. The latter favored the anti-discrimination approach and worked with Mintoren. That tension has persisted to this day.

Korean Ethnic Education and Multicultural Education

Since the 1990s, there have been changes in Korean ethnic education in Osaka Prefecture largely due to the shrinking size of the resident Korean population. An increase in the number of Koreans naturalizing to become Japanese citizens and the high rate of Koreans marrying Japanese nationals have contributed to this decrease.[69] In the early 1990s, Mukuge and Tokkabi, facing reduction in the number of Koreans participating in their programs, decided to include children of newcomer foreigners who had moved into the cities. By the early 2000s, their programs had become multiethnic, with only a few Korean participants.[70] Meanwhile, Osaka Mintoren disbanded in 1995 due to internal conflicts. In Osaka City, with a much larger resident Korean population, the reduction of the number of participants in ethnic classes has been taking place more slowly, and the number of ethnic classes is still increasing. Yet Korean instructors have noticed a rapid increase in the number of children of Korean–Japanese parentage with Japanese nationality.

The 20th anniversary booklet of Mukuge: It is Fun to be Ethnic

The 30th anniversary booklet of Mukuge: It is Fun to be Multiethnic

Multiculturalists in today’s Japan can learn much from the old practice of Korean ethnic education. The political interpretation of kyosei (living together) may be the most important idea. Facing children of foreigners, Japanese teachers need to deal with the question of how to live together with different nationals, a question hardly discussed in the imported literature on multicultural education.

To elucidate how this question was tackled in Korean ethnic education, let us compare the two approaches. Korean children were expected to develop different types of subjectivity: a Korean ethno-national subjectivity linked to the homeland and a political subjectivity committed to fighting ethnic discrimination in Japan. They were encouraged to develop different kinds of relationships with their Japanese schoolmates, who were taught to respect them as foreign nationals or to fight together with them against ethnic discrimination.

These differences arose from the different ways in which the two camps of people understood Koreans in Japan: as Korean nationals in the Diaspora or as zainichi seeking civil rights in Japan as an ethnic group. Japanese and Korean activists in the two camps collaborated differently. In one camp, they fought together as different nationals with each national group in charge of “teaching Korea correctly” or teaching ethnic classes. In the other, national boundaries could be crossed, and Koreans and Japanese could unite as comrades to fight together. The two camps sought to create different kinds of human relationships on the school campus and in society. Mintoren tried to create a society where Koreans and Japanese could live together without discrimination against ethnic minorities. ZOK and Minsokkyo also sought to achieve co-living between Koreans and Japanese, though they did not use the term explicitly until the 2000s. For them, it meant living together as different nationals on an equal footing.

The idea of co-living not only constituted the goal of activism for both camps but also shaped the process of their political activism. Let us examine this idea. The term kyosei has been interpreted in two major ways: as the concept of living together in harmony, and as a process of rectifying social inequality. The former meaning is used widely and the term usually refers to this meaning. The latter, a more critical and philosophical meaning, has been developed in the context of social activism, i.e., in civil rights movements for people with disabilities and for women. It refers to the process of trying to achieve co-living, rather than to the goal of co-living itself, though this goal is also called kyosei. Underlying this paradox is the realization that co-living is extremely difficult to achieve and requires a serious engagement in the process of attaining it. Kyosei as a political process is further differentiated by stressing in that process the political subjectivity of the oppressed or the sense of responsibility of the majority people.[72] In the ethnic education movement, Koreans and Japanese in both camps engaged in kyosei, taking their respective kyosei positions. Probably, the significance of this movement lies in the activists’ serious engagement in kyosei, though neither camp used this term to describe their efforts. The two camps thus shared a great deal in regard to the process of activism, despite their differences in political orientations and educational approaches.

From Korean ethnic education, multiculturalist teachers can learn how to grasp education in political terms. As discussed above, education focusing on newcomer children tends to be merely cultural, embracing the goal of living together in harmony, kyosei. Teachers can avoid this tendency by practicing kyosei as a political process. In fact, such efforts have already been made. The prevailing use of the idea of human rights in multicultural education policies can be traced to the anti-discrimination approach.[73] Teachers familiar with this approach pay close attention to political and social circumstances surrounding newcomer children.[74] Teachers dealing with newcomer children can also make use of the ethnic-culture approach and politicize their multicultural education in an international framework. As many of those children and their families maintain close ties with their homelands, teachers need to pay attention to Japan’s foreign policies, which shape their diasporic lives.

To be sure, both approaches had problems. The ethnic-culture approach was criticized for its association with Korean nationalist ideology, and the anti-discrimination approach for its reduction of Korean ethnicity to ethnic discrimination. Neither approach could escape the charge of essentializing Korean ethnicity. New generations of educators dealing with children of Korean descent need to tackle these problems as well as new problems while collaborating with those working with children of newcomers

One of the important problems in this collaboration is how to deal with ethnically hybrid children who are Japanese nationals. This problem points to the need to debunk the myth of homogeneity among people within national boundaries. It is a challenging problem in today’s Japan where the tide of nationalism and xenophobia is deepening the divide between “Japanese” and “foreigners.” Children of Korean descent have been subjected to assaults, verbal and physical, triggered by the 2002 confirmation of North Korea’s abduction of Japanese nationals, while children of newcomers have been perceived in relation to the idea of foreigners’ crimes exaggerated by the media. Multiculturalists need to intervene in this social climate not only by stressing kyosei but also by interrogating the concept of Japaneseness.

Conclusion: Korean Ethnic Education and Multicultural Co-living

Spreading in Japan simultaneously with neo-nationalism, the discourse of multicultural co-living (tabunka kyosei) can turn into “its own form of nationalism.”[75] The term kyosei as harmonious co-living has been used since the late 1990s by local and central governments as well as by business organizations concerned about the increasing numbers of newcomer foreigners. As David Chapman rightly points out, when used by those in positions of power, “the discourse of tabunka kyosei in Japan has much in common with the ways in which other nation-states attempt to manage diversity by the strategic inclusion of difference.”[76] The discourse is deployed to contain ethnic diversity within the three Fs and include disfranchised foreigners in a community of co-living with Japanese citizens as if they were equal to each other. Unlike the multiculturalism discourse that stresses national unity, this discourse is also used to exclude foreigners as different, and thereby to solidify Japanese national boundaries. Thus, the discourse of tabunka kyosei used by people in positions of power is both inclusive and exclusive, serving to protect cultural homogeneity and national boundaries. Analyzed this way, it is not very different from the assimilationist discourse of the multiethnic Japanese empire, which deprived colonized Koreans of their culture and language while at the same time propagating the idea of co-prosperity in East Asia.

It is this emerging hegemonic discourse of tabunka kyosei that Korean and Japanese activists involved in ethnic education are now fighting, while using the identical expression. By drawing on their own experience of educational activism and engaging in the political process of kyosei, they may be able to stay away from both the inclusive and exclusive forces of the hegemonic discourse, and find a way to rejuvenate ethnic education for children of Korean descent, which is central to the maintenance of the political and cultural presence of Korean ethnicity in Japan. This maintenance is important for Koreans, other foreign residents, and the Japanese themselves, precisely because it is a reminder that today’s multiethnic Japan should not repeat the past.

In the current stage of activism, the opposition between the two camps may be an asset. If the anti-discrimination approach with its concern about civil rights offers a way to combat the exclusive force, the ethnic-culture approach points to a way to maintain cultural difference and fight the inclusive force. The two approaches thus provide different strategies for combating hegemonic discourse. Moreover, they suggest multiple identity positions, a Korean (or Vietnamese) Japanese, a denizen, a Korean (or Brazilian) in the diaspora, and a transnational citizen, the positions that have already been taken by many under the influence of the two approaches. The multiplicity of identity positions among people of foreign descent may undermine the Japanese national boundaries that the hegemonic discourse is meant to protect.

This article extends and develops “Korean Ethnic Education in Japanese Public Schools,” Asian Ethnicity 8.1 (2007): 5-23. Eika Tai is Associate Professor at North Carolina State University. Her publications include: “Redefining Japan as ‘Multiethnic,’”: An Exhibition at the National Museum of Ethnology in Spring 2004,” Museum Anthropology (2005); “‘Korean Japanese’: A New Identity Option for Resident Koreans in Japan,” Critical Asian Studies (2004). For more information, open here.

This article was posted at Japan Focus on December 27, 2007.

Notes

[1] E. San Juan Jr., Racism and Cultural Studies (Duke University Press, 2002), 9.

[2] Carl A. Grant and Joy L. Lei, eds., Global Constructions of Multicultural Education (London: Lawrence Erlbaum, 2001).

[3] Nakajima Tomoko, Tabunka kyoiku to zainichi chosenjin kyoiku (Kyoto: Zenkoku zainichi chosenjin kyoiku kenkyu kyogikai, 1995), 45.

[4] Much of the following discussion is based on my fieldwork in Osaka between 2001 and 2006. I interviewed activists and researchers.

[5] Stephen May, “Critical Multicultural Education and Cultural Difference: Avoiding Essentialism,” in May, ed., Critical Multiculturalism: Rethinking Multicultural and Antiracist Education (London: Falmer Press, 1999), 5.

[6] Baogang He and Will Kymlicka, “Introduction,” in Kymlicka and He, Multiculturalism in Asia (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 23.

[7] Grant and Lei, Global Constructions, xv.

[8] Stanley Fish, “Boutique Multiculturalism, or Why Liberals are Incapable of Thinking about Hate Speech,” Critical Inquiry 23 (1997): 378-95.

[9] Matsunami Megumi, “Nyukama jissen ni miru kyoshi no ‘zainichi gaikokujin kyoiku’ kan,” in Nakajima Tomoko, ed., 1970 nendai iko no zainichi KankokuChosenjin kyoiku-kenkyu to jissen no taikeiteki kenkyu (Osaka: Poole Gakuin University, 2004),194.

[10] Enoi Yukari, “Tabunka kyosei kyoiku to kokusai jinken,” Kaiho kyoiku 397 (2001): 8-17.

[11] May, “Critical Multicultural Education,” 11.

[12] The new nationality law of 2000 allows children born in Germany to non-German parents to hold both a passport of their parents’ nationality and a German passport until age twenty-three. Germany has been increasingly seen as a country of immigration.

[13] Okano Kaori, “The Global-local Interface in Multicultural Education Policies in Japan,” Comparative Education 42.4 (2006): 473-91.

[14] San Juan, Racism, 9.

[15] Brett Klopp, German Multiculturalism: Immigrant Integration and the Transformation of Citizenship (London: Praeger, 2002), 187.

[16] Ralph Grillo, “Immigration and the Politics of Recognizing Difference in Italy,” in Grillo and Jeff Pratt, eds., The Politics of Recognizing Difference: Multiculturalism Italian-style (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2002).

[17] Okano, “Global-local.”

[18] Nakajima Tomoko, “‘Bunka’ ‘jinken’ ni okeru ‘kokoro-shugi’ to ‘kotoba-shugi,’” Human Rights Education Review 1.1 (1997): 25-30.

[19] Jeffry T. Hester, “Kids between Nations: Ethnic Classes in the Construction of Korean Identities in Japanese Public Schools,” in Sonia Ryang, ed., Koreans in Japan: Critical Voices from the Margin (New York: Routledge, 2000), 193.

[20] Lee Changsoo, “Ethnic Education and National Politics,” in Lee and George DeVos, eds., Koreans in Japan: Ethnic Conflict and Accommodation (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1981), 163-66.

[21] Ibid., 163-66.

[22] Sugitani Yoriko, “‘Kangaeru-kai’ no ayumi,” in Zenchokyo Osaka Kangaeru-kai, ed., Mukuge (Tokyo: Aki Shobo, 1981), 15-42.

[23] Mukuge, 30 (August 2001).

[24] Sugitani, “‘Kangaeru-kai’ no ayumi.”

[25] Lee, “ Ethnic Education,” 168-69. There were some schools affiliated with Mindan.

[26] Ozawa Yusaku, Zainichi Chosenjin Kyoiku-ron (Tokyo: Aki Shobo, 1973), 468.

[27] Sugitani, “‘Kangaeru-kai’ no ayumi.”

[28] Fukumoto Taku, “Changes in Korean Population Concentrations in Osaka City from the 1920s to the Early 1950s,” Jinbun Chiri 56.2 (2004): 42-57.

[29] Asahi Shinbun Osaka, 22 January 1957.

[30] Mukuge, 30 August 2001.

[31] Inatomi Susumu, Nihon Shakai no Kokusaika to Jinken Kyoiku (Osaka: Kinki Insatsu Puro, 2005), 3-5.

[32] ZOK is taken from the current name of the association, Zenchokyo Osaka Kangaeru-kai. ZOK publishes Mukuge, an organizational magazine.

[33] Mukuge 30, August 2001.

[34] Osaka-shi Minzoku Koshikai (OMK), Minzoku Gakkyu (Osaka: Yuniwârudo, 1997), 112.

[35] Sugitani, “Kangaeru-kai,” 21. Leftist members of ZOK were supportive of Chongryun, which defined its members as “overseas nationals of North Korea.”

[36] Mukuge, 30 April 1976.

[37] Mukuge, 30 August 2001.

[38] Mukuge, 30 August 2001.

[39] Japanese teachers donated money to support Korean lecturers.

[40] Mukuge, 30 August 2001.

[41] Inatomi, Nihon Shakai, 22.

[42] Sugitani, “Kangaeru-kai,” 22.

[43] Inatomi, Nihon Shakai, 26.

[44] Mukuge, 30 October 1976.

[45] Inatomi, Nihon Shakai, 6.

[46] OMK, Minzoku Gakkyu, 84.

[47] Sugitani, “Kangaeru-kai,” 27.

[48] Kishida Yumi, “Minzoku no tame no kyoiku to kyoiku no tame no minzoku,” in Nakajima, 1970 nendai iko, 42-59.

[49] Takatsuki City Board of Education (TCBE), Zainichi KankokuChosenjin mondai o kangaeru (Osaka: Takatsuki City, 1990).

[50] Mintoren, Hansabetsu to jinken no minzoku kyoiku o (Osaka: Mintoren, 1992), 12.

[51] Fukuoka Yasunori, Lives of Young Koreans in Japan (Melbourne: Trans Pacific Press, 2000), 63.

[52] Sonia Nieto, Language, Culture, and Teaching: Critical Perspectives for a New Century (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 2002), 246-7.

[53] Sonia Nieto, Affirming Diversity: The Sociopolitical Context of Multicultural Education (New York: Longman, 1992), 208-21.

[54] Kodokyo, Kodokyo 30-nen no Ayumi (Osaka: ABC Kobo, 1991).

[55] Asahi Gurafu, 25 April 1969.

[56] TCBE, Zainichi, 82.

[57] Kodokyo, Kodokyo, 70.

[58] Fukuoka, Lives, 65.

[59] Ibid., 66.

[60] Abdul R. JanMohamed and David Lloyd, “Introduction: Minority Discourse,” Critique 7 (1987): 5-17.

[61] Manuel Castells, The Power of Identity (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 1997), 8.

[62] Takatsuki Mukuge-no-kai (TM), Minzoku dakara Omoshiroi (Osaka: Mukuge-no-kai, 1992), 52.

[63] TM, Minzoku, 16-17.

[64] TM, Minzoku, 24.

[65] TM, Minzoku, 17.

[66] Kodokyo, Kodokyo, 74-82.

[67] Mintoren, Hansabetsu to Jinken no Minzoku Kyoiku o (Osaka: Mintoren Mintoren, 1992).

[68] Mukuge, 26 November 1979.

[69] About 10,000 Koreans have become Japanese nationals per year since the mid-1990s. More than 80 per cent of marriages involving Koreans are interethnic.

[70] Tai Eika, “Korean Activism and Ethnicity in the Changing Ethnic Landscape of Urban Japan,” Asian Studies Review 30 (2006): 41-58.

[71] The Korea NGO Centre was created in 2004 out of Minsokkyo and two other groups.

[72] Eika Tai, “‘Multicultural Co-living’ and its Potential,” The Journal of Human Rights 3 (2003): 41-52.

[73] Okano, “Global-local.”

[74] Matsunami, “Nyukama,” 196.

[75] Michelle Anne Lee, “Multiculturalism as Nationalism: a Discussion of Nationalism in Pluralistic Nations,” Canadian Review of Studies in Nationalism XXX (2003): 103-23.

[76] David Chapman, “Discourses of Multicultural Coexistence (tabunka kyosei) and the ‘Old-comer’ Korean Residents of Japan,” Asian Ethnicity 7.1 (2006): 89-102, 100.