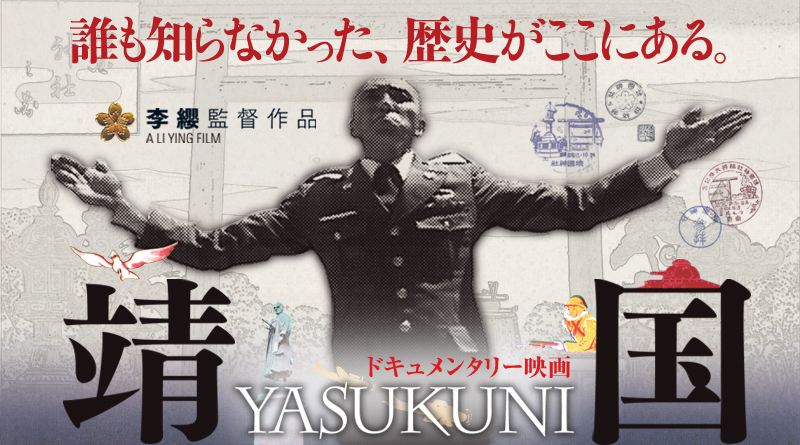

Abstract: Neo-nationalists forced the cancellation of the theatrical launch of a Chinese-directed movie about Japan’s controversial war memorial Yasukuni in early April, 2008. In the weeks that followed, the incident became a cause célèbre, with some 30 film, media, and civil liberties organizations issuing declarations of protest. A number of theaters throughout Japan signed on to screen the film, and its Tokyo premiere was scheduled for May 3.

Introduction by David McNeill

Its name translates as “peaceful country,” millions have silently prayed there for an end to wars, and for much of the year the loudest sound is the buzzing of insects and the shuffle of old footsteps to the hushed main hall. Yet Yasukuni Shrine, which occupies a single square kilometer of central Tokyo, is one of the most controversial pieces of real estate in Asia, resented by millions who consider it a monument to war, empire, and Japan’s unrepentant and undigested militarism.

A decade ago when Chinese director Li Ying began filming there he didn’t know what to make of his mysterious subject either. Today, as he watches the official Tokyo launch of his two-hour movie “Yasukuni” go down in flames amid death threats and cancelled screenings, he says the shrine symbolizes a “disease of the spirit” in Japan. “That I haven’t been able to leave this issue alone for the last ten years means that I too am suffering,” explained the 44-year-old Guangdong native.

“I didn’t really want to make such a difficult film…so I must be sick to do it. The point is to look directly at the disease.”

Li’s point appears to have been lost by Japanese conservatives, who have branded the movie “Chinese propaganda,” and condemned a decision by the Agency for Cultural Affairs of Japan to award Li a 7.5 million yen (approx. $75,000) grant. In March, the film’s distributors were forced to give a private preview to 80 lawmakers after a weekly tabloid launched a campaign against the decision to fund it. With criticism growing along with the threat of ultra-right-wing violence, four Tokyo cinemas pulled out of an official launch on April 12. But it appears the squelching of the film may only be temporary. As of May 1, nearly two dozen theaters around the country had announced plans to screen the film.

The campaign against the movie is led by powerful Liberal Democrat (LDP) lawmaker Inada Tomomi, who says it is guilty of “political propaganda.” “I felt the movie’s ideological message was that “Yasukuni was a device to drive people into an aggressive war,” she told the Asahi newspaper after the screening, but denied she wanted it banned. “I have no interest in limiting freedom of expression or restricting the showing of the movie. My doubt is about the movie’s political intentions.” Inada can be seen in Li’s documentary speaking at the shrine on the 60th anniversary of Japan’s surrender, Aug. 15, 2005. “We are committed to rebuilding a proud Japan, where the prime minister can openly worship at Yasukuni,” she tells the crowd. “We will devote ourselves to speeding the day when the Emperor too can worship here.”

Inada is a leading historical revisionist. Right-wing webcaster Sakura Channel lists her as a supporter of its movie “The Truth of Nanjing”, which argues that the 1937 rape of the old Chinese capital by Japanese Imperial troops is a lie. She helped lead a lawsuit against novelist Oe Kenzaburo , who angered neo-nationalists by writing about the military’s role in forcing civilians to kill themselves during the 1945 Battle of Okinawa. Osaka District Court exonerated Oe in March, but the plaintiffs have promised to appeal. Inada is a signatory to a now famous 2007 Washington Post advertisement claiming that the sexual enslavement of thousands of Asian women had no basis in fact, and a member of a parliamentary group fighting against what it sees as “masochistic” teaching of history in the nation’s high schools.

“In a now familiar pattern, ultra-nationalists who follow in the shadow of establishment politicians, threatened retribution against anyone who handled the movie. Anonymous bloggers posted contact details for the distribution company, the Japan Arts Council and every theatre showing it. Anonymous death threats have been issued against Dragon Films, the company that produced “Yasukuni.”

The attempt to bury Li’s film follows a string of similar incidents. In February, Tokyo’s Grand Prince Hotel New Takanawa cancelled a conference by the Japan Teacher’s Union – a popular ultra-right target — after learning that 100 right-wing sound trucks turned up to last year’s conference venue. The hotel’s decision has been bitterly attacked by union officials.

Scholars have also lined up to criticize a government decision that they say effectively refused to allow the Italian scholar Antonio Negri to enter the country last month. Mr. Negri, an anti-globalization activist and philosopher who served a prison sentence in Italy on controversial charges of “insurrection against the state,” had been scheduled to give a series of lectures at the Universities of Tokyo and Kyoto. He was forced to abruptly cancel his trip after being told he would need a permit to entry the country.

“My sense is that we have entered a very dangerous period for freedom of expression and press freedom in this country,” says Tajima Yasuhiko, a professor of journalism in Tokyo’s Sophia University. “That is the background to these cases. The idea that people are entitled to express different opinions and views is withering. That should be common sense, whether one is on the left or the right.”

Why was the movie canned? The cinemas say they were disturbed by right-wing threats and the possibility of “trouble,” particularly during the first days of screening. “We very much regret canceling the documentary but we felt we had no choice after considering the safety of our customers,” explains Murayama Yaseyuki, a spokesman for Q-AX Cinema in Shibuya. But Director Li rejects these claims and says only political pressure explains the sudden decision by all four Tokyo cinemas to pull the plug.

“Before the movie was released I visited the theatres and talked to the managers,” he says on the phone from China. “Some magazines had already started discussing the movie, so we knew that there would be some protests. There was a very strong sense among everyone then of wanting to put this movie out and challenge the protesters. So why have they all suddenly changed their mind? I can only conclude that pressure was exerted behind the scenes.” For the English subtitled video of a more recent statement by the director, see here and here.

Japan has been here many times before. Because of neonationalist protests, few Japanese have seen Paul Schrader’s 1985 art-house cinematic tribute to Mishima Yukio. How many people here will see the dozen or so movies made to commemorate the 1937 Nanjing Massacre over the last two years in Europe, North America and China? The pattern is often the same: The movies pick at the scabs of Japan’s war history, conservative politicians express “concern” and the ultra-right go into battle.

“Politicians know that when they make pronouncements about these issues that we will take action,” says Takahashi Yoshisada, who heads a Tokyo-based ultra-nationalist group. Like most other ultra-nationalists, including the group that first spooked the Ginza Cinepathos movie theatre with a visit in March, Takahashi has not seen “Yasukuni,” only heard about it from people like Inada. “They talk, we protest. They know this because it has happened many times in the past. In that sense, I think the politicians are using us.”

In a recent press conference to foreign reporters in Tokyo, Councilor Inada defended her criticism of Li’s movie. “Wouldn’t China have a problem if a Japanese company [funded by tax money] in China created a film conveying the message of the Dalai Lama?” But the comparison is rejected by Professor Tajima. “Liberal democratic nations are not afraid of some criticism. Expecting everyone to just cheer on the country and cooperate with the government is more like North Korea or the situation in Tibet.”

Speaking at the Foreign Press Club, veteran Japan commentator and Keizai University professor Andrew Horvat said the debate about Li’s movie worried Japan’s friends as much as its enemies. “I’m afraid that Japan’s reputation as a democratic country will come under scrutiny.” But conservatives have cheered the cancellation of the screenings. “Our tax money should be not spent to support a film that expresses an anti-Japan ideology,” wrote one right-wing blogger. “This is just common sense.”

The controversy over Yasukuni is not difficult to understand. Among the 2.46 million war dead enshrined there are over 1,000 war criminals, including the men who led Japan’s brutal pillage of Asia. A museum on the shrine’s grounds audaciously rewrites history: teenage suicide bombers (Kamikaze) are heroes, America is the enemy and the Emperor, supposedly reduced to mortal status after Second World War, is still a deity. The Shinto officials who run the shrine believe they are protecting the “soul of Japan.”

Li’s cinematic gaze is unflinching, and sometimes disturbing. In one scene, filmed on the 60th anniversary of Japan’s World War 2 surrender, August 15, 2005, two young anti-Yasukuni protestors are beaten and chased from the shrine’s grounds by right-wingers who yell at them to “go back to China.” The protestors, who are Japanese, are later hauled off by the police. Archive shots show Japanese soldiers using Yasukuni swords, forged in the grounds from 1933-1945, to decapitate Chinese victims.

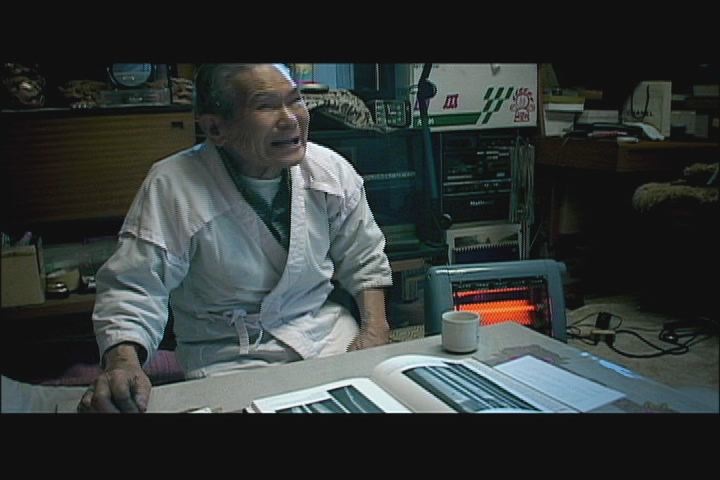

But much of the movie, which is narration free, unobtrusively explores the conflicting sentiments provoked by the memorial among ordinary Japanese: from the two older women who recall the battlefield deaths of relatives and who want the prime minister to pay his respects, to the Buddhist priest who resents the fact that his father’s soul has been enshrined there against his will. The movie is hinged around the work of the shrine’s last remaining sword-maker, Kariya Naoji, a gentle craftsman who offers few insights into how he helped forge the 8,100 swords that ended up on the battlefield.

Many have been quick to blame the cinemas for the “Yasukuni” debacle. The Asahi and Sankei newspapers, representing the left and right of mainstream public opinion in Japan, have both urged the theater managers to rethink their decision. One newspaper called the collapse under threat “pitiful.” But you can hardly blame the theaters for running scared, says Japan-based film director John Junkerman, who wrote the subtitles for “Yasukuni.”

“There have been a sufficient number of violent attacks for alleged ‘anti-Japanese’ thought crimes that the threat of violence is very intimidating,” he says, citing several cases including the murder of Asahi journalist Kojiri Tomohiro in 1987, the shooting of Nagasaki mayor Motoshima Hitoshi in 1990″ and the most recent fire-bomb attack on the home of LDP politician Kato Koichi, after he criticized prime ministerial visits to Yasukuni. “Couple this with the apparent reluctance of the police to intervene to prevent intimidation, and the threat that the theaters perceive is not actually unreasonable.”

Junkerman acknowledges that Japan has “a very high level of respect for and exercise of freedom of expression.” But the branding of a movie as “mondai-saku” — or a “problem” — in the press is a potent way for politicians to raise questions about its political slant, and “the right wing take over from there.” Ultra-nationalists are like the mad dogs kept in bad neighborhoods: not nice to be around but useful in an emergency.

One of the more interesting developments, then, in the continuing saga over Li’s movie, is how little support Inada appears to have among neonationalists, who believe she has betrayed them. “That woman is the worst,” says prominent new-right figure Kimura Mitsuhiro. “First she criticizes the movie, then refuses to back the protests against it. She did a complete about-face.”

At a Shinjuku meeting about the “Yasukuni” movie in April, another senior new-right activist, Suzuki Kunio, argued that ordinary Japanese should have a chance to judge for themselves what all the fuss is about. “I think it is a mistake for politicians to decide what is best for the public to see,” he said.

There are signs that Suzuki may get his wish as the smear campaign against the movie runs out of steam. As of May 1st, as many as 20 theaters around the country plan to screen the film, which has now become a sort of free-speech cause célèbre. Chief Cabinet Secretary Machimura Nobutaka and even Prime Minister Fukuda Yasuo have gone on the record to call the harassment of the movie “inappropriate.”

For his part, director Li Ying, who moved to Tokyo in 1989 and speaks fluent Japanese, rejects claims that he is anti-Japanese and describes his movie as a “love-letter” to the Japanese people. “I live in Japan. How could something that is anti-Japanese be good for me, personally? This love letter may be hard to watch, but that’s the form my love takes.” He says he was motivated to start making the movie a decade ago by the shock of listening to Japanese revisionists at a conference on the Nanjing Massacre. “When it comes to history, there’s a gap that’s so large.”

John Junkerman interviews Li Ying

[Note: This interview was conducted on March 10, several weeks before the theaters in Tokyo decided to cancel their screening of the film.]

Q: Who is the diet member who has raised objections to the film?

Li: Inada Tomomi is a very famous lawyer. She was involved in the court case over the “Hyakunin-giri” affair [the 1937 contest between two Japanese officers to be the first to behead 100 Chinese] and in the suit against Oe Kenzaburo, regarding mass suicides in Okinawa. She’s got very powerful backers. An ordinary diet member would not be able to get the Agency for Cultural Affairs to take action. So it’s intimidating. And now she’s influencing people around her. It’s a month until the film opens, and she can make things difficult for us. We don’t really care if she threatens us personally, we’re prepared for that, but it’s the theaters we’re worried about. The theaters are taking out insurance, increasing security. And the other concern is that people who appear in the film might be threatened. The other day I met with Kariya Naoji [the Yasukuni swordsmith featured in the film] and he mentioned that he’d seen reports that it was an anti-Japanese film. He doesn’t think so himself, but it could be a problem if he hears that from other people.

Q: What motivated you to breach the taboo and make a film about Yasukuni?

Yasukuni and the Nanjing Massacre

Li: It was Nanking. Some years ago, I was thinking about making a film on Nanking. In speaking with Japanese, of course there is always a gap in the perception of history. And the gap surrounding Nanking is the widest. So I was interested in Nanking and in 1997 I attended a symposium at Kudan Kaikan in Tokyo on the 60th anniversary of Nanking. The first event of the symposium was the screening of a documentary about Nanking. It was a propaganda film produced by the Japanese military, and of course it didn’t touch on the massacre at all. There was a scene of the formal ceremony of the Japanese military entering the city. And something happened that I couldn’t believe. The audience applauded, very loudly. It was a shock. It left me shaking. I couldn’t believe it. I felt like I was standing on a battlefield. It was a shock to experience such a scene, here in Japan so many years after the war. It’s unthinkable, that people still feel a sense of honor and pride toward such a scene. This is not simply a typical right-wing problem. It far surpassed what I understood to be the right wing. Kudan Kaikan is a fancy venue, and there were more than a thousand people, all wearing suits and ties. University of Tokyo professors, members of the Atarashii Kyokasho o Tsukuru Kai [Japanese Society for History Textbook Reform]. There are those in Japan who have documented the massacre, and there are those who deny it. It was the deniers who were participating in this symposium. And what is their position? They dismiss the testimony of those who were in Nanking, and argue instead that the massacre never happened. There’s no possibility of discussing it with them.

At the symposium, the daughter of one of the officers who engaged in the beheading contest appealed for the restoration of her father’s honor, that he be treated not as a war criminal but as a heroic soul in Yasukuni. So that made me wonder what Yasukuni symbolized, this sacred space that granted heroic status. This was an issue that had a greater sense of reality. Nanking is a historical problem, but to take up an issue that carries reality, you need to film in Japan, and that meant filming Yasukuni, to bring the issue into present reality. Yasukuni feels very real to me. So I began filming then and continued for ten years. I didn’t know what kind of film it would turn out to be. I decided I would just film every time I went to Yasukuni. As I filmed I would study and learn more, and figure it out. That’s a very time-consuming process, to start filming without knowing what kind of film it will turn out to be. But I had a sense that it raised very real issues.

Q: Did people try to prevent you from filming?

Preventing the Filming of Yasukuni

Li: My camera was taken away, videotape was taken, I was told to erase the tapes. It was right-wingers who did this. You could never make this film, shooting in the standard way. I think that’s why no Japanese has ever made a film like this. They would follow the ordinary process of applying for press passes and permission, but it doesn’t work to take that approach. All you can do is shoot a bit at a time. When it was possible, I applied for permission. But there are places where permission wouldn’t be granted, and you either have to go ahead and film there, or give up.

Q: This is one of the issues that is being raised in criticism of the film.

Li: I did get permission to film on August 15th. I gave my name card to the people in charge at Yasukuni, and I had permission to film then. In the beginning, I had no idea of what kind of film I would make, so I shot like a tourist. There are a lot of tourists who shoot video at Yasukuni. But when I understood there were things I needed to shoot, I got permission. The people in charge knew who I was. I never shot with a concealed camera. I didn’t use a long lens.

Q: Was making a film about Yasukuni something of a provocation?

Li: It was more like a conditioned response than a provocation. I was provoked, and I responded. I often say, this is a sequela, the psychological aftereffect of the war. Not just World War II, not just the war with China, but it’s a disorder caused by all the wars Japan fought since the Meiji period. Yasukuni Shrine is intricately tied to Japan’s modern history. It was built by the Meiji emperor, it’s the emperor’s shrine. So it is these contradictions, this disorder caused by war that can be seen on the stage of Yasukuni. When I go inside there, I feel like I too am suffering from a disease. I contracted the disease at the Nanking symposium, and I’ve been suffering from it ever since. I’m not a doctor, who can diagnose someone’s disease. I’m suffering from the disease as well. So it’s not a provocation, but a conditioned response, I’m responding by instinct.

Tojo Hideki and “Pride”

I had a dialogue once with Ito Shunya, the director of “Pride.” We’re both members of the Directors Guild of Japan, and Ito has always been very cordial and friendly toward me, a Japanese gentleman. But around that same time, 1997, he made the film called “Pride.” That too was a shock. When it comes to history, there’s a gap that’s so large. It’s a film about the “pride” of Tojo Hideki, his defiance of the Tokyo war crimes trial, arguing that the war was fought in Japan’s self-defense. We had a special meeting of the international committee of the Guild and I engaged in a three-hour discussion with Ito. And I thought at the time that it was pointless to debate, that what I needed to do was respond with a film of my own. So, it’s matter of conditioned response. The other side is provocative, I’m just responding by instinct.

Q: So you don’t consider this film to be anti-Japanese.

Curing the disorder caused by war

Li: Of course not. What’s wrong with curing an illness, the disorder caused by war? The point is to live together in a healthy atmosphere, and that would work in Japan’s favor as well. People don’t want to recognize their illness, they don’t want to think about it, look at it. They say, “Japan is beautiful. How can you say it is sick?” But if you watch the film, you’ll see that diseased cells are living within the space of Yasukuni. And that’s dangerous. It could lead to heart disease, or to brain disease. But what’s really serious about this disease is that it comes not from internal organs but from the soul. So it is a psychological disorder, a disease of the spirit. That I haven’t been able to leave this issue alone for the last ten years means that I too am suffering from this psychological disorder. I didn’t really want to make such a difficult film, it’s only going to cause problems, so I must be sick to do it. The point is to look directly at the disease.

What is the meaning of Yasukuni?

I’ve been observing for ten years, and this is the result. The film asks the question: What is the meaning of the spirit of Yasukuni? That’s all. Each viewer can come up with his or her own answer. This has to be good for Japan. It’s an opportunity, an opportunity to get well. That’s good for Japan, not anti-Japanese. To suggest that the film is anti-Japanese suggests that Yasukuni symbolizes all of Japan. That’s a mistake to begin with. It’s one face of Japan, the face of Japan when it’s suffering from disease. That’s not all of Japan. Japan has many beautiful faces. But this face must not be ignored. It must be confronted. Many Japanese don’t know about Yasukuni, they feel it has nothing to do with them. But that’s wrong. It needs to be recognized, looked at, and thought about, and the film provides that opportunity. So it’s not anti-Japanese. It’s my love letter to Japan, in that sense. I live in Japan. How could something that is anti-Japanese be good for me, personally? This love letter may be hard to watch, but that’s the form my love takes. There are many forms of love. There’s one that declares that everything is wonderful, but that’s not my way. This is my expression of love.

Q: But there are those who consider it a taboo to address this.

Li: That’s because it is questioning the spirit, and so the spiritual pain comes out, and there is resistance. I’m not stating a conclusion. We don’t use any narration. The space itself raises the questions, the atmosphere of the place. My theme is the space that is Yasukuni. The space and the spirit. It’s the spirit of Yasukuni that I’m trying to capture. So you need a variety of perspectives to see the space. It’s not one-sided. But no one has looked at that space, so seeing it may be a shock, it may be unpleasant, but it’s reality.

Q: What is the spirit of Yasukuni?

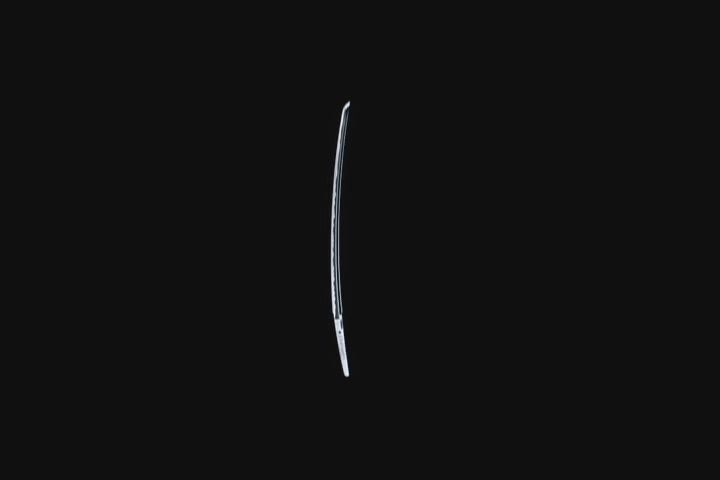

The spirit of Yasukuni: the sword

Li: In the shrine’s own doctrine, the spirit is the sword. It is the object of worship. All of the spirits of the dead are embodied in that sword. So that’s the symbol of Yasukuni. The film depicts symbolic meaning. Everyone who appears in the film, every scene, and the sword itself, all are symbols. I am using the doctrine of Yasukuni to make a film: the world of symbols. The sword is the spirit, but what meaning does that spirit have? That’s the question the film raises. Is it the samurai spirit? The Yamato spirit? An entirely beautiful spirit?

Q: But it is a spirit that doesn’t allow for reflection.

Li: They are all tools. The sword is a tool. Yasukuni itself is no more than a building. It’s a tool. What meaning do people invest in those tools? How they are used changes their effect entirely. So it always returns to people. How do people use these tools, how do they see them? How do they interact with the tools? People are weak, so the government uses the tools to manipulate people.

Q: There are many war memorials in the world, and everyone who visits them brings their own meaning to them. But Yasukuni does not allow that freedom. The compulsory nature of Yasukuni is the key problem, it seems to me.

Yasukuni and State Shinto

Li: It began as a symbol of the state. Under the emperor, it was part of a political religion. It was a military facility. The head priest was a general in the army, for example. It was run by the military. During the war, it had a status that surpassed all religions, it represented the morality of the Japanese people. That was the nature of state Shinto. State Shinto conveyed the power of the state as the image of the nation. The problem comes after the war, when state Shinto was disestablished, and separation of religion and the state was adopted. Yasukuni became an independent religious institution. But is it really independent? Is it really simply a religious shrine? There are many contradictions there. For example, in the film, there’s the story of the Buddhist priest, Sugawara Ryuken. The question he asks is this: if Yasukuni is an independent religious institution, how did it obtain the information needed to enshrine his father? He was enshrined, as a heroic spirit, after the war. How could they accomplish that? His father was a Buddhist. Why does a Buddhist have to be enshrined in a Shinto shrine? That’s a contradiction. Even after the war, there is no separation between Yasukuni and the government. The enshrinement rolls are all prepared on the basis of information that comes from the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare. That’s true of the Class-A war criminals too. All of that information came from the government. So the government is still using Yasukuni.

The Japanese government employs a double standard. With regard to international society, it recognizes the verdicts of the war crimes trials, it acknowledges the existence of war criminals. But domestically, it uses Yasukuni to honor them, and give them the status of heroic souls, to express gratitude and respect. This is very Japanese, a different face at home and abroad. And this double standard has created the contradictory nature of Yasukuni over these decades. So there are people with different stances and the confrontations among them are repeated. It also makes Yasukuni very indefinite. To young people, it’s perplexing, and they don’t want to have anything to do with it. And this connects, of course, to the larger question of Japanese war responsibility throughout the postwar period. It is the matter of collective memory, and that’s where coercion comes into play. In the film, everyone is part of a collective, it has nothing to do with the individual. They have collective memory, they are in a collective context, collective currents and relationships. Yasukuni is a powerful collective symbol, a powerful symbol of collective memory. It is a symbol of Japan as a kyôdôtai, a communal society. To live collectively, with gratitude to the dead. It’s that kind of symbol. Yasukuni is not a simple symbol of militarism, it’s not simply a matter of whether the prime minister will worship there or not. It is connected to the collective memories that stretch back to the beginning of the Meiji period, when Japan began to walk the path of a modern state, with pride and honor.

Q; How do you think the film will be seen in China?

Li: This film is a Japanese-Chinese coproduction, with producers from the Beijing Film Academy and a Chinese film company. So it will be released in China. And that’s important, because it depicts sides of Yasukuni that have never been shown before.

Q: But there is a chance it will lead to increased anti-Japanese sentiment.

Li: That’s possible, but until now Yasukuni has been used for political purposes, with a nationalist spirit on both sides. But this film shows many aspects of Yasukuni, so it may have the effect of dampening the nationalist response. It provides the opportunity to engage the subject calmly, to watch, feel, study, and relate to it. An opportunity to communicate not in a political, nationalistic way, but in a cultural way.

Q: There are many appealing characters in the film, starting with Kariya-san, the swordsmith, and some of the ordinary people who worship at the shrine.

Li: The spirit of the artisan is a central aspect of the Japanese character. There’s a concentration on the work in front of one. But there is also a tendency to not think about what is done with the product of one’s labor, and that’s problematic. That can be used by the state again, as it was during the war. Soldiers went to war doing a job, they didn’t go to war as “devils.” They were all ordinary people, and it was their job. Then they were changed. They may have engaged in atrocities, but it was war, so it’s forgivable. Is that kind of thinking acceptable? The film poses that question to the Japanese people.

Germany, Japan and the war dead

The desire to remember the war dead is the same throughout the world. When I showed the film at the Berlin Film Festival, the response was interesting. There are many war dead in Germany, and they had families who have their grief and want to commemorate the dead. But the Germans first built a memorial to the Jews. There is no facility in Germany commemorating the German war dead. Why is that? The founder of the International Forum of New Cinema at the Berlin festival, Ulrich Gregor, has an interesting take on this. He argues that the difference between Germany and Japan is that Germany was lucky to have gotten rid of its emperor after World War I. For Japan, the symbol of the state has remained the same, before, during, and after the war. The emperor has lost his authority, he made a declaration of his humanity, but he remains the symbol of the state. That’s the source of the difficulty and complexity of the problem. Yasukuni Shrine is the emperor’s shrine. The film calls that into question. And that’s the reason it has generated an intense response.

Article and interview were prepared for Japan Focus. Posted on April 1, 2008 and updated May 1, 2008. This is a substantially expanded and updated version of an article that was published in the South China Morning Post.

See also Li Ying and Sai Yoichi, Yasukuni: The Stage for Memory and Oblivion, A Dialogue between Li Ying and Sai Yoichi