Dead Men Walking: Japan’s Death Penalty

David McNeill & C.M. Mason

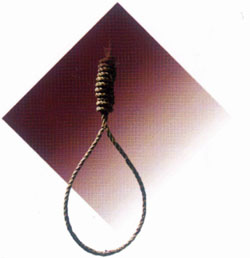

Japan’s death penalty is cruel, secretive and out of step with much of the developed world say its opponents. As a record 97 men and 5 women await the hangman’s noose, one man alive and free who knows its true horrors speaks.

After breakfast on Christmas Day, 2006, three Japanese pensioners and a middle-aged former taxi-driver were given an hour to live. The men were told to clean their cells, say their prayers and write a will. Fujinami Yoshio, 75, scribbled a note to his supporters before he was taken to the gallows of the Tokyo Detention Center in a wheelchair. “I cannot walk by myself, I am ill and yet you still kill such a person,” he wrote. “I should be the last person executed.”

Also struggling to walk and partially blind, Akiyama Yoshimitsu, 77, had to be helped by prison guards to the execution chamber. Both men were appealing their convictions for murder. Fujinami attacked his ex-wife’s family with a knife in Tochigi Prefecture in 1981, killing two of her brothers and robbing the family. His defense argued that he was addicted to amphetamines and had snapped after his in-laws prevented him from meeting his estranged wife.

Akiyama was convicted of murdering a factory boss in Chiba in 1975 and robbing him of 10 million yen. For the rest of his life, he maintained that his brother Taro bore most responsibility for the crime. Fukuoka Michio, 64, also claimed he was innocent of killing three people, including his wife’s sister, in Kochi Prefecture over three years from 1978, protesting that the police forced his confession and ignored his alibi.

The fourth man, 44-year-old Hidaka Hiroaki, was a serial killer who had lured four women, including a 16-year-old high-school student, into the taxi he drove in Hiroshima before raping, robbing and murdering them, all in 1996. He rejected his lawyer’s appeals for a stay of execution, saying he wanted to die.

All four were hanged with military precision at three different venues within minutes of each other; blindfolded, handcuffed and bound at the ankles before a 3-cm-thick rope was slipped around their necks and a trapdoor opened beneath their feet. They had a collective age of 260 and had waited in some cases a quarter of a century for the hangman’s rope. By the time families, lawyers and supporters were told, their bodies were already growing cold in prison morgues. Relatives – if they had any — had 24 hours to pick up the corpses.

According to Amnesty International, 102 people are waiting to be hanged in one of Japan’s seven execution chambers, the largest number in over half a century. The hangmen are undeterred by age, senility or handicap: The condemned include 86-year-old Ishida Tomizo, convicted of a 1973/4 rape and double-murder, and 81-year-old Okunishi Masaru, who has protested his innocence of poisoning five women for over four decades. Opponents of the death penalty believe that several death-row inmates are clinically insane, driven there by the burden of solitary confinement and sometimes waiting decades for the prison guards to stop outside their cell door.

“There is a clear tendency after the year 2000 for a rise in the number of death sentences, a phenomenon related to the crime situation,” says Teranaka Makoto of Amnesty International Japan. “The Police Agency repeatedly emphasize that serious crime is worsening but the statistics don’t show this. What is true is that the police have made more new crimes, such as stalking, and that media coverage has enormously expanded, so we have a kind of moral panic, with people talking about crime much more.”

Despite the recent expansion in the prison population, Japan incarcerates its citizens at a far lower rate than most developed countries: 58 per 100,000 people compared to 142 in Britain and 726 in the United States; and executes fewer people than either the US or China, the world’s leading death-penalty state. The Japanese Justice Ministry can also point to low rates of recidivism and – for some the ultimate test – safer streets than most of those countries.

But Japan is bucking a worldwide abolitionist trend: 128 countries have scrapped their execution chambers, including the Philippines and Cambodia and a growing number, including South Korea and Taiwan are debating abolition. By contrast, support for the death penalty is increasing here. A 2005 government poll found for the first time over 80 percent of Japanese people “in favor” of executions (in “unavoidable circumstances”) a rise of over 23 percent since 1975. Just six percent want the system abolished.

Why is Japan, which uniquely prohibited the death penalty during the Heian period for three and a half centuries, swimming against the tide? Activists cite a lack of debate.“There is no discussion about this in the media,” says Hosaka Nobuto, Secretary-General of the Parliamentary League for the Abolition of the Death Penalty. “Even in the Diet, the death penalty is something of a taboo because most lawmakers know the abolitionist cause is unpopular. It has become a vicious circle: Politicians don’t discuss it and the public doesn’t hear the abolitionist case, so the politicians continue to avoid it.”

Hosaka says the Christian lobby in most other countries, including Europe, the Philippines and South Korea, has been a major factor in moving those countries toward abolition, despite often strong public support for executions. “Religious groups in Japan cooperate in the death penalty,” he said. Scholars note, however, that ‘significant controversy’ exists within Buddhism about support for the death penalty. Brian Victoria, professor of Japanese Studies at Antioch College and director of their Buddhist Studies in Japan Program points out that “Japan’s single largest traditional Buddhist school, the Shin (True Pure Land) school, has taken a very clear stand against the death penalty and continues to distribute literature and otherwise agitate for its abolition.”

Japan’s system has proved immune to condemnations from the Council of Europe, Amnesty International, the United Nations Human Rights Commission and the country’s own abolitionist lawmakers, such as Social Democrats Oshima Reiko and SDP President Fukushima Mizuho. It has also survived a brief moratorium on executions from 1990 to 1992 (seven people were executed the following year) and the tenure of justice ministers who apparently opposed state killings, such as the devoutly religious Sato Megumu, who held the post during the moratorium, or Sugiura Seiken, who refused to sign execution orders throughout 2006. Eventually, the bureaucracy re-imposes its will, as it did last Christmas. “We absolutely wanted to avoid ending the year with zero executions,” an anonymous Justice Ministry official told the Asahi newspaper after Fujinami and his fellow prisoners were hanged. The official said the system would “break down” if the number of death-row inmates exceeded 100. New minister Nagase Jinen has re-asserted government policy.

The particular cruelties of death row in Japan have been widely criticized: inmates are deprived of contact with the outside world, a policy designed to “avoid disturbing their peace of mind” say ministry officials; kept in solitary confinement and forced to wait an average of more than seven years, and sometimes decades, in toilet-sized cells while the legal system grinds on. Decisions about who is to be executed and when often seem arbitrary, but when the order eventually comes, implementation is swift. The condemned have literally minutes to get their affairs in order before facing the noose. There is no time to say goodbye to families. Because the orders can come at any time, the inmates, in effect, live each day believing it may be their last.

It is the high probability of mistakes, however, that really keeps opponents awake at night. Half a century after the torture and framing of Menda Sakae (see panel) the criminal courts still rely heavily on confessions for proof of guilt. “Nothing has changed since I was arrested,” says Menda. Failure to admit a crime is frowned on, notwithstanding the right to silence or even innocence of the charge. The police, therefore, have every incentive to extract a confession and, with up to 23 days to interrogate a suspect, the blunt tools to do so. “It is almost certain that there are more innocent people waiting to be executed in Japan,” claims Ishikawa Akira, one of the country’s leading abolitionists, and a parliamentary secretary to Fukushima.

About half of the people on death row claim they are not guilty of all or part of the charges for which they have been condemned. They include former pro-boxer Hakamada Iwao, a death-row inmate who has protested his innocence of murdering a Shimizu family for four decades. One of the three judges who sentenced Hakamada in 1968 said last month he believes he deserves a retrial. “I thought [the evidence produced at the trial] did not make sense,” said Kumamoto Norimichi, who nevertheless went along at the time with the 360-page judgment. Hakamada’s application for a retrial has been rejected by the Tokyo High Court and the Supreme Court.

Critics of police methods have been heartened by the acquittal last month in Kagoshima District Court of 12 people accused of vote-buying in 2003 prefectural elections. The presiding judge ruled that the 12 “appear to have made confessions in despair while going through marathon investigations” by police who “likely goaded them to confess.” The Kagoshima police chief who presided over the investigation, Inaba Katsuji, has since been promoted to a senior position in the Kanto National Police Agency.

There seems little real momentum, however, to reform the criminal justice system. Indeed, with growing social cracks opening up in the landscape of “beautiful Japan and lurid crime stories never far from the front pages, some believe the police, courts and judges will fall back on the tried-and-tested methods that sent Menda to prison for 34 years. “The government is using the image of rising crime to introduce their own methods to control the social order,” says Teranaka who sees the death penalty as a “symbolic” issue. “I fear that the number of executions will continue to rise.”

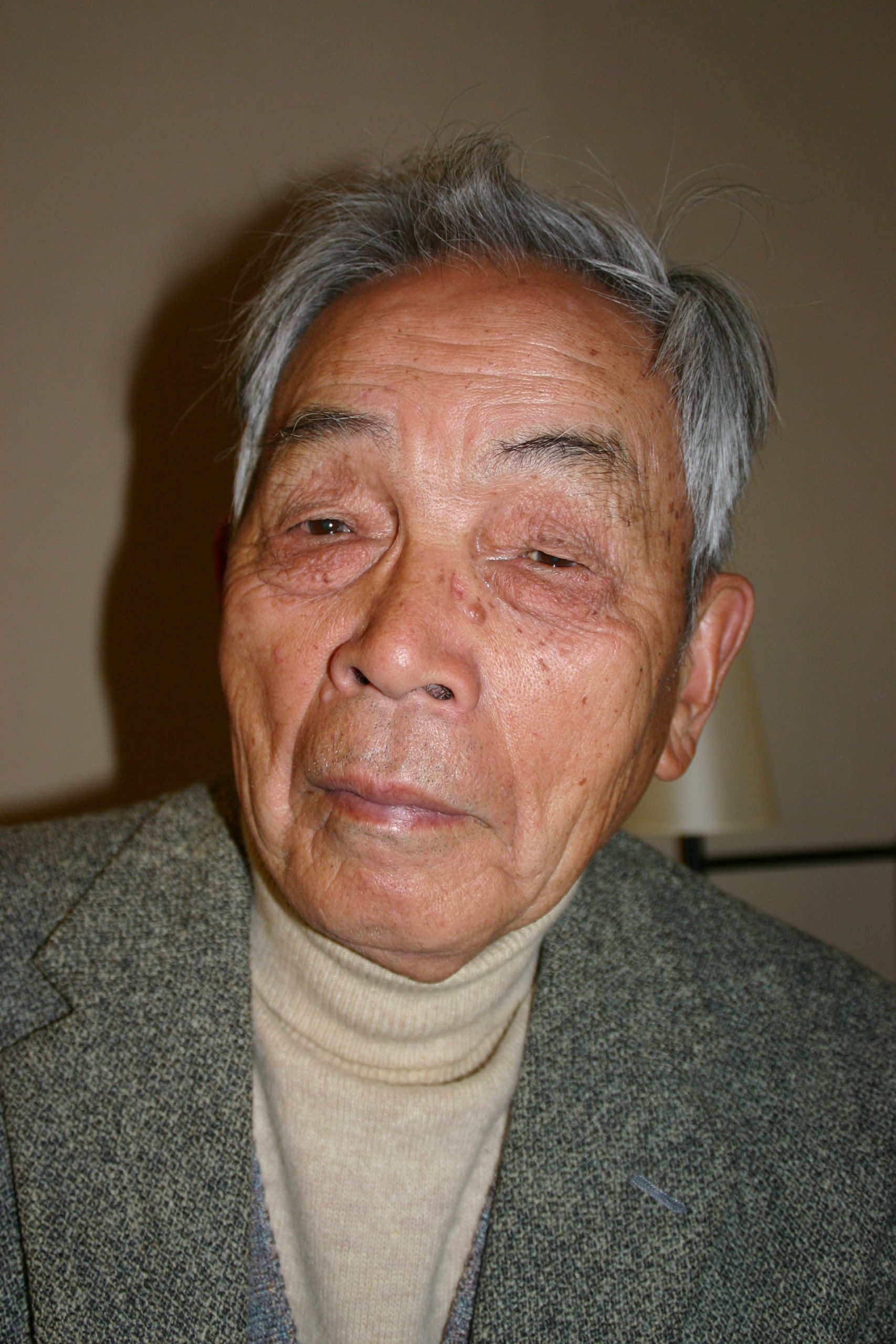

The man who lived to tell the tale

When his body isn’t groaning under the weight of its 81 years and the sun is shining in the skies over his native Kyushu, Menda Sakae sometimes forgets the ordeal he suffered and knows he is lucky to be alive. But most days there is no blotting out that the Japanese state stole 34 years of his life, or that he thought every one of those 12,410 days would be his last. “Waiting to die is a kind of torture,” he says, “worse than death itself.”

Early on Dec. 30, 1948, a killer broke into the house of a priest and his wife in Kumamoto Prefecture and used a knife and an axe to murder them and wound their two young daughters. In the dirt-poor early postwar years, life was cheap and a black market thrived in most parts of Japan. The killer could have been anyone, but penniless, uneducated farmhand Menda was in the wrong place at the wrong time and was arrested on a separate crime of stealing brown rice.

The police detained him for three weeks without access to a lawyer until they extracted a confession. During interrogation, the 23-year-old was starved of food, water and sleep and beaten with bamboo sticks while hung upside down from a ceiling. Menda signed a statement written by the cops and was convicted of double homicide on Christmas Day 1951. He wouldn’t step outside Fukuoka Prison until 1983.

Life shrank to a 5-square-meter unheated solitary cell, lit day and night and monitored constantly. His parents cut him off. “They came once before sentencing. Even after I filed for a retrial and sent them letters they didn’t want to accept my innocence.” He says they came again after he appealed to them via a friend. “After that, they came to see me when they disowned me. That was the last of it.”

From his cell, he heard one of his fellow inmates dragged to the gallows for the first time, an event that he says made him “insane” and caused him to scream so long he was awarded chobatsu: a two-month stint with his hands cuffed so he had to eat like an animal. Every morning after breakfast, between 8 and 8:30 am – when the execution order comes — the terror began afresh. “The guards would stop at your door, your heart would pound and then they would move on and you could breathe again.”

Menda would watch dozens more inmates carted off to the gallows. “The men would yell out as they left: “I will be going first and will be waiting for you,” he once told Australian TV, saying there were “no words” to describe the feelings of those left behind. Menda’s wife Tamae calls it a “miracle” that he stayed sane. “He is very short-tempered and stubborn,” she says. “I think he survived because he wasn’t educated and couldn’t make sense out of what he was going through.”

The abyss was never far away, but the closest Menda came to walking over the edge was when his Buddhist chaplain told him to accept his fate. “I asked him why and he said because Buddhist teaching says, ‘As a man sows, so shall he reap.’ He told me that it was decided in my previous life that I was to be executed and that unless I accept what was handed to me my parents, siblings, friends and acquaintances would not be saved.” Instead, Menda converted to Christianity and began reading the bible and translating books into Braille, a hobby that sustained him through the years of solitary confinement.

In 1983, after 80 judges and half a lifetime of struggle a court finally acknowledged the police had concealed his alibi and he became the first person to ever escape Japan’s death row (three others, all tortured into confessing have since been released). He was 54. In return for stealing the best years of his life, the government gave him 7,000 yen a day for every day he was in prison: 90 million yen in total, half of which he gave to a group campaigning to abolish the death penalty. “I had to pay lawyers and pay back my debt. I only have a third left.”

Now married, Menda is one of the world’s leading death-penalty abolitionists. He traveled to France this year to Paris to speak at the World Congress against the death penalty. He says he knows the mentality of the condemned man better than most. “I have met so many death-row inmates, and I know that they didn’t have any reasoning behind their crimes. They told me that they felt rage and don’t remember anything afterward. People kill others because they are not normal. When people kill, they are not themselves. They forget who they are.”

Over two decades of freedom has not dimmed his hatred for the police, the judiciary or what he calls Japan’s feudal attitude toward justice and democracy. He points out that the system that tore his life apart is still unchanged: the police can still hold a criminal suspect for 23 days, confessions still carry enormous weight, over 99 percent of criminal charges end in victory for the prosecution, and the condemned are still kept in solitary confinement with virtually no chance of a reprieve. “The powerful have the upper hand here,” he says.

“I went to see the police when I was released and asked them how they felt about what they did to me. They told me they were just doing their job.” He remains pessimistic that the system will change. “When I was released, people took up the cause (of abolition) but gradually lost interest. Japanese democracy is only 60 years old. The concept of human rights is not engrained in our history.”

“A judge once said it was natural to sacrifice one or two citizens for the sake of Japan’s judicial stability. But I believe there is nothing crueler than a government taking away a life. It is all too human to make a mistake…or just happen to cause problems. In this sense, I am for abolishing the death penalty.

The execution chamber

The gallows, like much of the rest of Japan’s prison system, are shrouded in thick veils of government secrecy. Executions are timed to coincide with Diet recesses to avoid protests from opposition lawmakers, prison guards are forbidden from discussing their work and few ordinary civilians have ever set foot inside an execution chamber. The Justice Ministry never publicly releases the names of the people it kills.

Media enquiries are swatted away. The ministry declined to answer most of the questions put to it for this article, including who pushes the execution button, the number of inmates on death row or even how many people are present during a hanging.

Three years ago, a small party of ministers fought and won the right to see the gallows, the first time in three decades the Ministry granted access to a political delegation. In 2001 a human rights group from the Council of Europe was refused permission to meet a death-row prisoner, despite a direct request from the prisoner himself. The delegation was told that meeting the inmates “might disturb their peace of mind” and were shown an empty cell.

Still, a handful of former insiders have illuminated Japan’s ultimate legal sanction and the people who carry it out.

According to writer and former executioner Sakamoto Toshio, prison guards are rotated every three years to prevent them building up feelings of empathy with their charges. Like the prisoners, the guards are told on the day of an order when an execution is to be carried out. Discussing the details of their work or whether they have actually put a rope around somebody’s neck is “taboo”, says Sakamoto, who claims the stress of working on death row sends some to psychiatric hospitals. “Nobody talks about the rights of the men who do this work,” he says. “No matter how psychologically strong they are, guards get mentally and physically exhausted serving inmates on death row because it is truly cruel.

Former prison-guard-turned lawyer Noguchi Yoshikuni says on the morning of an execution two burly guards strong enough to control a resisting man take the condemned prisoner by each arm and lead him to a concrete room. A Buddhist or Christian altar, the prison warder and a curtain concealing the other half of the room are among the last sights he will see. The curtain is pulled back to reveal a glass encased room and the prisoner is asked if he has any final words.

“It is not unusual for the men to say thanks to the guards or apologize for causing them trouble,”according to Noguchi. Sakamoto says he has seen men being dragged kicking and screaming to the gallows, calling out for their mothers. Death-penalty opponents believe that inmates have been beaten if they resist, citing the case of Nagayama Norio, who was executed in 1997 and cremated before his lawyer could inspect his body.

Inside the room, three guards wait with hands on three buttons. The prisoner is handcuffed, hooded and bound at the feet and a rope is pulled around his neck. The guards push the buttons but do not know which one has been rigged to open the trapdoor beneath the prisoner’s feet. Below a doctor, waiting with a prison official, checks the heart of the hanging man. They wait for five minutes to make sure of death and then take the body down, put it in a coffin and ship it to a prison morgue. In most cases, says Sakamoto, the bodies are never picked up. “Most of the time the remains are buried in the prison graveyard or the bodies donated to hospitals for medical research,” he told a Japanese magazine recently.

Both men have come to different conclusions from their work. Noguchi opposes executions and leads a group of campaigners trying to win more access to prisons. “Killing people won’t cut crime,” he says. “There is absolutely no data to prove this, and there is always the possibility that innocent people will die.” But in his book Shikei wa ikani shikkou sareruka (How the death penalty is conducted), Sakamoto says the death penalty should be kept, as the ultimate deterrent…but never used.

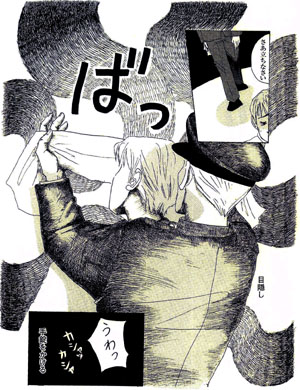

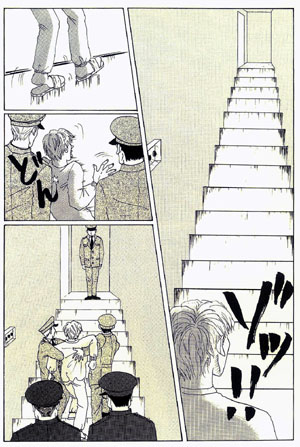

The condemned’s last steps toward oblivion

¨In his 2003 book titled “Shikei wa ikani shikkou sareruka (How the death penalty is carried out),” former death-row prison guard Toshio Sakamoto includes a section graphically illustrating what no cameras are allowed to record — the last moments in a condemned prisoner’s life. Here, a selection of illustrated pages from Sakamoto’s book gives a chilling taste of capital punishment in action in Japan.

Dead man’s daybreak: A prison guard comes into a

28-year-old death-row inmate’s cell one morning.

The guard only tells the inmate to accompany him

“to the office,” but the inmate soon realizes that he

is being led elsewhere.

Reality dawns: The inmate is taken to a room where a

spiritual adviser awaits. By now he knows exactly what

is happening to him. He is told he is allowed to write a

last letter.

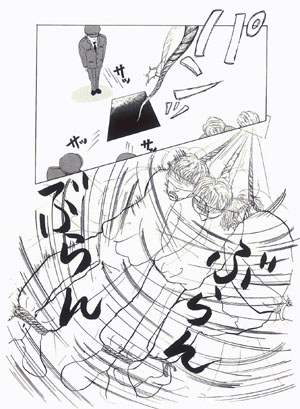

The last breath: Having written his final letter, the inmate

is blindfolded, handcuffed and bound around the ankles,

with death now only moments away.

The guards’ perspective: Prison officers blindfold and

handcuff the condemned inmate, put a rope around his

neck and position him standing on the trapdoor of the

gallows. On a signal, three guards then press buttons

that open the trapdoor.

Job done: The trapdoor opens and the inmate is hanged.

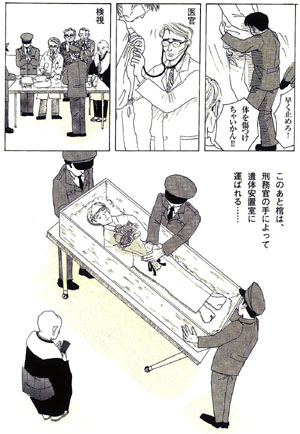

Disposal: Guards pull down the body after waiting 5

minutes to ensure death. Then a doctor checks there

are no life signs before the cadaver is put in a coffin

and taken to the prison morgue. In most cases, the

bodies are never collected and are either buried in

the prison graveyard or donated to a hospital for use

in medical research.

David McNeill writes regularly for the Chronicle of Higher Education, the London Independent and other publications. He is a Tokyo-based coordinator of Japan Focus.C. M. Mason is a freelance writer based in Tokyo. This article was written for The Japan Times, where it appeared on April 8, 2007. This revised version appeared at Japan Focus on April 28, 2007. Many thanks to Brian Victoria and William Drew for their comments on the original article.

Sources

Sakamoto Toshio, “Shikei wa ikani shikkou sareruka — Moto keimukan ga akasu” (How an execution is conducted: recounted by a former prison guard), Publisher: Nihon Bungei sha.

Menda Sakae Gokuchu Nooto – watashi no miokkuta shikeishu-tachi. Publisher: Impakutoo Shuppankai. (Menda Sakae’s prison diary: The friends I lost).