Family Skeletons: Japan’s Foreign Minister and Forced Labor by Koreans and Allied POWs (Japanese translation available)

By Christopher Reed

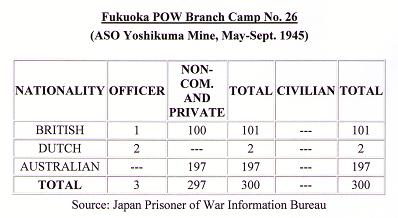

Aso Mining Company had been producing coal to fuel Japan’s modernization for nearly 70 years by the time Aso Taro, Japan’s current foreign minister, was born in 1940. Faced with a severe heavy labor shortage as the China war gave way to the Pacific War, Japanese industry increasingly turned to Korean, Allied POW and Chinese forced labor. Some 10,000 Korean forced laborers toiled under miserable conditions for Aso Mining. In addition, it is now emerging that 300 Allied prisoners of war performed forced labor at Fukuoka POW Branch Camp No. 26, better known as the Aso Yoshikuma coal mine. Two-thirds of the prisoners were Australian; one-third was British; two were Dutch.

None of these 300 men ever received payment for their work or an apology from Aso Mining or the Japanese government, much less from the sitting foreign minister. The company’s Korean labor conscripts received wages in theory, but in practice the bulk of salaries were withheld during the war and ultimately were never paid. Soon after the war companies like Aso Mining deposited unpaid wages for Korean and Chinese forced labor with the Bank of Japan, which continues to hold the money today.

The cold intransigence is part of a well-established pattern. For six decades the Japanese state and corporations have refused to apologize or pay reparations to any of the hundreds of thousands of Koreans and the tens of thousands of Allied POWs and Chinese who became victims of corporate forced labor within wartime Japan. Relatively little is even known about the millions of so-called “romusha,” Asians who worked against their will for the Japanese empire across vast stretches of the Asia Pacific, after being nominally liberated from the yoke of Western colonialism.

Aso Taro, after heading the family business for most of the 1970s, followed in the family tradition and entered politics, eventually becoming his country’s top diplomat—as well as a leading neonationalist who seeks to affirm the legitimacy of Japan’s goals and conduct during World War II. Moreover, he is among the leading candidates to replace Koizumi Junichiro when he retires as prime minister in September.

The contrast to European and North American handling of forced labor and other lingering World War II issues is instructive. Germany has chosen a path of reconciliation by proactively settling wartime forced labor accounts. The “Remembrance, Responsibility and the Future” Foundation was established in 2000, with funding of some $6 billion provided by the German federal government and more than 6,500 industrial enterprises. As reparations payments drew to a close in late 2005, about 1.6 million forced labor victims or their heirs had received individual apologies and symbolic compensation of up to $10,000. Similarly, the Austrian Reconciliation Fund recently finished paying out nearly $350 million to 132,000 workers forced to toil for the Nazi war machine in that country, or their families. Beginning in the mid-1990s, Swiss and French banks and insurance companies paid hefty restitution for assets looted from Holocaust victims. In 1988, both the US Congress and the Canadian Parliament granted official apologies and individual compensation of $20,000 to ethnic Japanese who had been interned during the war.

Today activists in China, the Koreas, the West and Japan are demanding that the historical reality of widespread forced labor by the Japanese state and private sector be honestly recognized and redressed. Information is a key to these transnational reparations movements, and the article below by Christopher Reed, drawing on the contributions of Japanese and international researchers, succeeds in doing what Japan’s mass media has consistently failed to do. Reed provides a clear account of the Aso family’s deep ties to forced labor and Aso Taro’s personal leadership of the company. At a time of mounting regional tensions, which the Foreign Minister himself is fueling, Reed asks the logical question: is Aso Taro fit to head Japan’s foreign policy establishment? —William Underwood]

While Aso Taro’s public statements as foreign minister have only exacerbated tensions between Tokyo and the rest of Asia, a family connection to wartime forced labor has raised further questions over his ability to oversee good relations with Japan’s neighbors.

During World War II, the Aso family’s mining company used thousands of Koreans as forced laborers. This legacy of Koreans, Chinese and other Asians being coerced into slave-like working conditions across the region more than six decades ago has become an issue in Tokyo’s maintenance of normal diplomatic relations in East Asia. Awareness of the fact that 300 Allied POWs also performed forced labor at an Aso coal mine is now spreading in Western countries.

Japanese Foreign Minister Aso Taro

Aso’s family background, and his personal refusal to engage the issue, has led some to suggest that his position as foreign minister is untenable.

Meanwhile, recent research by a group of historians in Kyushu has provided new details on the role of the Aso family in using Korean labor before and during the war. The Korean pit workers, according to the historians, were systematically underpaid, underfed, overworked, and confined in penury. Forced to toil underground, they were watched by guards 24 hours a day. Their release came only with Japan’s 1945 defeat.

Aso himself ran the Fukuoka company from 1973-79, when he entered politics. During that time he did not address its history of using forced labor, nor has he since, while he continues to maintain his relationship with the firm. This stance forecloses the possible argument that at 65, Aso has the excuse of a generational separation.

GERMAN REACTION

According to one German Embassy official in Tokyo, speaking on the understanding of anonymity, while family lineage on its own would not be held against an individual in his nation, Aso’s actions here make him an unsuitable foreign minister by German standards. “Because Aso’s family connection gave him the opportunity to address wrongs in the firm, and he did not do so,” as well as comments that “seem to defend criminal policies of the past,” Aso would “not be acceptable” for a post such as foreign minister. “He might get into parliament,” said the official, “but not into government.” The Foreign Ministry in Tokyo did not respond to inquiries on the issue.

The Chinese foreign minister, Li Zhaoxing, also recently quoted a German government official’s puzzlement over the “silly act” of Japanese prime minister Koizumi Junichiro’s continuing visits to the Yasukuni shrine in Tokyo, where 14 Class-A war criminals are enshrined. A German leader, the government official told Li, would never worship at the burial places of Adolf Hitler or convicted Nazi war criminals.

Such thoughts from Germans are reinforced by Aso’s espousal of Japanese racial supremacy, such as displayed in a remark in a speech at the opening of the Kyushu National Museum in Fukuoka last October. Then, he described Japan as “one nation, one civilization, one language, one culture, and one race, the like of which there is no other on earth.” It was an observation that echoed Japan’s fascist period of 1930-45.

Japanese media scholars have expressed concern at the lack of detailed reporting on Japan’s corporate forced labor, and on Aso’s family’s role in particular. “As Aso is a candidate for prime minister in September, his attitudes and his behavior are political issues,” says Hanada Tatsuro of Tokyo University. “The question of his qualifications is an important subject that should be opened to the Japanese public.” Hanada as well as Ofer Feldman, an author and Japan political scholar, blame Japan’s kisha press club system, in which journalists keep quiet about controversial issues that might harm their contacts, for media silence on the Aso connection.

CORPORATE HISTORY

The Aso family coal mining business dates back to the 19th century in Kyushu’s rich Chikuho coal fields in Fukuoka. Aso’s great-grandfather, Takakichi, founded the firm in 1872. At one time it owned over half a dozen pits in Kyushu and was the biggest of three family corporations mining an area producing half of Japan’s “black diamonds.”

The issue of the foreign minister’s family links to Korean wartime forced labor has already arisen in meetings between Japan and South Korea. Choi Bong Tae, a member of a bilateral commission studying the issue of forced labor, told reporters in November that the Japanese side had provided no information on the Aso company and others it had named. A spokesman for the Aso Group, the successor company of Aso Mining, said that it would be difficult to provide such data since records aren’t available from that long ago.

However, research conducted by Kyushu historians has provided new information on the role of the Aso family in exploiting Korean labor before and during the war. Hayashi Eidai, Ono Takashi, and Fukudome Noriaki, all now retired, drew on official and local library resources to gather contemporaneous statistics and reports on the Aso family’s mining operation, some of which Hayashi published in books.

Documents outlining work requirements at a POW mining camp

According to the company’s own statistics, by March 1944, Aso mines had a total of 7,996 Korean laborers, of whom 56 had recently died. Some 4,919 had managed to escape the forced labor regime. Across Fukuoka, the total fugitive figure amounted to 51.3 percent of the forced laborers. At Aso Mines, the figure was 61.5 percent, “because their record was worse,” said Fukudome. Data compiled by the Kyushu trio shows that Korean workers at Aso Mines were paid a third less than equivalent Japanese laborers to dig coal. It amounted to 50 yen a month, but less than 10 yen after mandatory confiscations for food, clothes, housing and enforced savings. The enforced savings, to discourage attempts at escape, often remained unpaid. Workers toiled for 15-hour days, seven days a week, with no holidays. A three-meter high fence topped with electrified barbed wire ringed the perimeter.

In 1939, the Japanese government passed the National General Mobilization law, which forced all colonial subjects, including Koreans, and those in Taiwan and Manchuria, to work wherever needed by Tokyo. The Kyushu historians have documented the fact that Aso Mining was shipping Korean laborers to Kyushu as early as the mid-1930s, before the law was passed. Although precise numbers are unavailable, an estimated 12,000 laborers passed through the company, some necessitated by a strike of 400 miners in 1932. After 1939, the historians calculate, the number of Asians kept in forced labor throughout the Chikuho region swelled.

The Aso Group has changed names more than once and in 2001 entered a joint venture with Lafarge Cement of France, the world’s largest cement maker. Aso’s younger brother Yutaka remained president of what became Lafarge Aso Cement Co. Last December, the French ambassador in Tokyo awarded Yutaka the Legion d’Honneur at a champagne reception. Guests of honor were Aso Taro and his wife, Chikako.

FAMILY BACKGROUND

It seemed a fitting tribute to a family steeped in Japan’s recent aristocratic traditions. Aso is the scion of a family of landed gentry throughout the 19th century. His great-great grandfather, Okubo Toshimichi, a samurai, was one of five powerful nobles who led the 1868 overthrow of the centuries-old shogunate era that ushered in modern times in Japan. Aso Taro graduated from Gakushuin University, which traditionally educates Japan’s imperial family, spent time at London University, joined what was then Aso Industries, and quickly became a director. Appropriate to his high-born antecedents, he joined the Japanese rifle shooting team in the 1976 Olympics in Montreal.

Aso’s grandfather, Yoshida Shigeru, served as prime minister of Japan five times between 1946 and 1954. An autocratic conservative, conveniently for the Aso family, he conducted a 1950s purge of “reds” in the coal mining unions. Chikako adds to the family’s upper-class luster as the daughter of Suzuki Zenko, Liberal Democratic Party prime minister from 1980-82.

There is even a royal link. Aso’s sister Nobuko married Prince Tomohito of Mikasa, the emperor’s cousin, recently in the headlines over his opposition to a woman occupying the chrysanthemum throne. Tomohito suggested continuing the male line through concubines, an imperial tradition that would move Japan back several centuries.

With his history of relatives who occupied senior political positions, Aso follows both a tradition and a type of thinking largely unchanged for many decades. Including the prime minister himself, Koizumi’s cabinet contains six men directly related to former premiers, government ministers, or Diet members. A seventh, regional minister Chuma Koki’s father, was mayor of Osaka. Koizumi’s grandfather and father were ministers, and his cousin a kamikaze pilot who dove to his death in 1945. He shares the ‘divine wind’ relationship with chief cabinet secretary Abe Shinzo, but his kamikaze-trained father never made his ultimate flight. Instead he rose to be foreign minister from 1982-86.

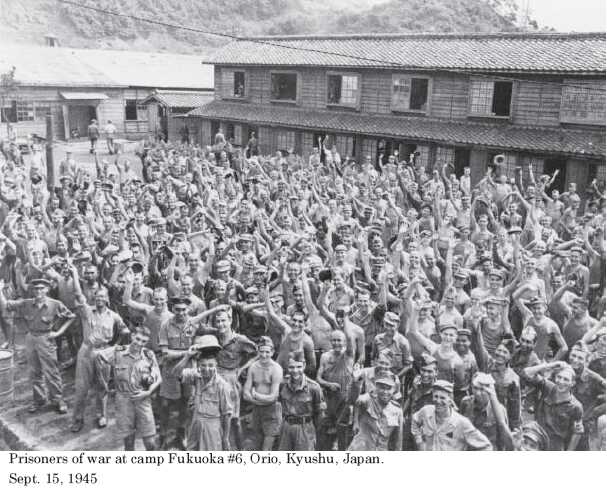

Liberated Allied POWs at a Kyushu prison camp on September 15, 1945

Abe, frontrunner to succeed Koizumi as prime minister next fall, is also the grandson of Kishi Nobusuke, who spent three years in Sugamo Prison as a Class-A war crimes suspect. Remarkably, Kishi went on to become prime minister from 1957-60, in which capacity he actively blocked efforts by Japanese activists and the Diet itself to obtain government records about Chinese forced labor — the war crime that Kishi himself helped perpetrate as a wartime cabinet minister in charge of economic production and munitions. (For details see a previous Japan Focus report: Chinese Forced Labor, the Japanese Government and the Prospects for Redress.)

These backgrounds may help to explain the frame of mind that has produced the series of provocative, neonationalist remarks by Aso, such as the museum speech claim about Japanese uniqueness. These have angered Japan’s neighbors, particularly China and the Koreas, through their reiteration of colonialist attitudes. The museum remark ignored Japan’s actual racial origins, and its lack of the homogeneity that many falsely claim. Aso appeared oblivious to the presence of his country’s aboriginals, the Ainu of Hokkaido, who bear physically different biological characteristics, and the people of Okinawa. Both these populations have their own languages, and anthropologists and archeologists have long agreed that the mainland Japanese owe their origins to several areas of Asia.

NEONATIONALIST AGENDA

Aso has recently claimed that Koreans who changed their names to Japanese ones under colonial rule by Tokyo from 1910-45, did so voluntarily. This ignored a law passed by Japan that compelled them to do so and imposed penalties and direct pressures on those who refused. In early February he added that Taiwan’s present high educational standards resulted from compulsory education, “a good thing” imposed by Japan during its colonial rule over the island from 1895-1945.

An ardent supporter of honoring Japan’s war dead at Yasukuni, Aso did appear to overstep what was acceptable to his LDP colleagues in January. He said that Emperor Akihito should visit the shrine, but this was immediately downplayed by political colleagues who clearly wished to disassociate themselves and the party from his urgings. The current emperor has in fact never visited Yasukuni and his continued absence is surely (though not stated publicly) related to the war criminals, who were enshrined — a better word might be “sanctified” in view of their divine status “kami” — in Yasukuni since 1978. The late Emperor Hirohito never visited the shrine after that.

Foreign minister Aso has also publicly supported the Yushukan museum, which adjoins Yasukuni and proudly advances a revisionist historical narrative. Yushukan, remodeled in 2002, glorifies Japanese war conduct through relics such as a locomotive from the notorious Thai-Burma railway, the forced labor construction of which caused the death of 16,000 Allied prisoners of war and 100,000 Asians.

Aso’s persistently provocative remarks prompted the New York Times, in an unusual move, to editorialize against Aso on February 13. Under the headline “Japan’s Offensive Foreign Minister,” the newspaper accused him of being “neither honest nor wise in inflammatory statements about Japan’s disastrous era of militarism, colonialism and war crimes that culminated in the Second World War.” It added that “public discourse in Japan and modern history lessons in its schools have never properly come to terms with the country’s responsibility for such terrible events as the mass kidnapping and sexual enslavement of Korean young women, the biological warfare experiments carried out on Chinese cities and helpless prisoners of war, and the sadistic slaughter of thousands of Chinese civilians in the city of Nanjing [December 1937-February 1938].”

It was perhaps an oversight that the Times did not mention enforced serf labor in its list of Japanese war crimes, but like every other major mainstream newspaper it has ignored the Aso family’s involvement in this. I first detailed the conditions at Aso mines for the coerced Korean laborers (and, I have since discovered, British and Australian prisoners of war) on February 2 in CounterPunch, the US-based online political website. Since then as a working journalist, I have tried to publish the details in various mainstream publications, without success.

MEDIA INDIFFERENCE

Rejection or silence greeted my attempts at the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Le Monde, the Washington Post, the Toronto Star, the Globe and Mail in Canada, the Sydney Morning Herald, the Age of Melbourne, the Australian, the Bulletin news magazine of Australia, and the Observer and the New Statesman in UK (almost all of which know of my work). Rejections in Japan came from the Shukan Kinyobi, Shukan Post, Shukan Sekai, and Shinchosa. The only taker was Sisa Journal in South Korea. My rewritten CounterPunch article was then printed in the April issue of Number 1 Shimbun, the monthly news publication of the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Japan, where I am a member. This is read by bureau chiefs of every major newspaper and television channel represented in Japan, as well as by many Japanese journalists. Yet I continued to hear nothing until a colleague suggested I contact the Japan Times. It accepted my Aso article and ran it on April 25.

This account of editorial rejection is not the grumblings of a slighted correspondent (I have been and continue to be published and broadcast elsewhere), but an important insight into media attitudes in these times. Some editors brushed off my “pitch” with the remark that it was old news. This was untrue. Although such media as the BBC and agencies had made passing references to the Aso slave-labor involvement, these were in the form of allegations made in South Korea, and took up no more space than a paragraph. Such dismissals were in fact a belated rationale for a reluctance to delve into the embarrassment of a major (conservative) political figure in Asia. The fact remains that not one major Japanese or foreign mainstream media has published a detailed account of Japan’s foreign minister’s connection to forced labor in wartime Japan, despite its being readily available.

Liberated Korean laborers assisting American GIs

The entire episode has reinforced the impression formed soon after my return to Japan last year after an absence of 30 years. It has not become more “westernized” and liberal, as so many commentators, particularly on the business side, like to claim. On the contrary, its underlying rightist nationalism with the attendant suppression of unsuitable news is emerging once more. Yet at the very time when observers should be most alert, they are failing in their duty to scrutinize.

In the 1970s, we young correspondents in Tokyo were mostly unaware of the hideous record of Japan’s atrocities and its iron fist in the rest of Asia. The words “colonialism” and “fascism” were never uttered. The US Occupation’s decision to sanitize Emperor Hirohito had much to do with this, for exonerating the man at the top made it risky to dwell on what happened under his ultimate jurisdiction. Now that the truth has mostly come out, Western commentators are under another influence that manifests itself in a similar way. They downplay Japan’s ugly past this time, not as an excuse or diversion from the imminent Cold War rhetoric against Soviet communism, but as an excuse or diversion from a possible Asian Cold War. Nothing must detract from the freshly minted diatribes against China as the latest “communist” menace to a free world — its “considerable threat” in Aso’s words.

The mendacity of this current propaganda was recently encapsulated by Kawata Takuji, Yomiuri’s deputy international news editor. In the daily edition’s English translation of April 28, he complained about China’s “high-handed” attitude toward Japan’s high-ranking Yasukuni worshippers. Not one word from Kawata on the half century in which Japan slaughtered, plundered, raped, and ravaged China, and for which it has yet to atone or make suitable amends. Nor did he mention the growing tendency in Japan to deny that those events even happened.

Not for a minute did I expect on returning to Japan after 30 years that the main obstacle to its enjoyment of normal peaceful foreign relations would be the refusal to come to terms effectively with the horrors it committed more than 60 years previously. Yet that is the case. The subject will not go away, but grow larger. In fact, Foreign Minister Aso seems to be doing his best to keep the process going.

This is an expansion of the article in The Japan Times, 25 April 2006. Posted at Japan Focus on May 6, 2006. Christopher Reed is a British freelance journalist who lives in Japan, where he was first a correspondent in the 1970s. He worked for many years as the correspondent in California for the Guardian of Britain.

Wes Injerd’s extensive research on Allied POW camps in Japan is available at his website.