C. Peter Timmer

[1]The G8 Summit has come and gone, and with it a missed opportunity for Japan to take center stage for helping to resolve the world rice crisis. Although significant relief from the peak rice prices in April has already been achieved, in part due to an early announcement by Japan that it would release some of its imported rice stocks, there has been no follow-up by the Japanese government to sustain the momentum achieved in May, and to keep rice prices falling back to levels more affordable by poor countries and poor consumers.

Background

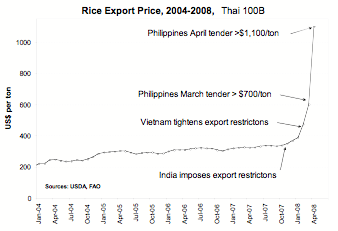

The world rice market is in crisis. Export prices soared to $1,100 per ton in April, from $375 per ton in December. [2] In April, there was concern that if action was not taken, prices might double again, returning them to stratospheric real levels last seen during the crisis in 1973/74.

The loss of rice production in Myanmar due to Cyclone Nargis complicated the task of stabilizing the world rice market. Fortunately, the announcement in May of a release of rice stocks by Japan helped bring rice prices down, to between $700 and $800 a ton in July. But the possibility of cutting them in half by the end of June was not realized, as Japan took no further steps, despite considerable international pressure. Even after the U.S. government took the lead in making this happen, it seemed that Japan was not willing to “take yes for an answer.” To its credit, the U.S. needed to get U.S. rice growers on board with the plan, a potentially difficult roadblock, but one that was successfully overcome. The mystery is why Japan has failed to respond.

Why food aid isn’t the answer

The alternative to getting rice prices down is hard to contemplate. Unless prices are brought down quickly, hundreds of millions of people will suffer from hunger and malnutrition—and many will die prematurely. Food aid won’t do the trick: There is simply no financial, logistical or political way that the world’s poor rice consumers can be saved by food aid. Instead of focusing solely on marshalling food aid resources, the global community needs to take immediate action to help solve the world rice crisis. What is needed is leadership on getting new rice supplies to the world market, and the G8 Summit seemed the ideal platform for action, because Japan is sitting on a significant source of these new supplies.

How can this be done? After India banned all non-Basmati rice exports in February, Vietnam largely withdrew as a seller from the export market (until July, 2008, when exports resumed), and Thailand struggled to maintain rice exports at last year’s near-record level (which required drawing down government-held stocks). As a result, the new rice supplies must come from a non-traditional source. Fortunately, such a source is available: unwanted rice stocks in Japan.

Japan uses high quality imported rice as animal feed

Because of its WTO commitments under the Uruguay Round Agreement, Japan imports a substantial amount of medium-grain rice from the U.S. and long-grain rice from Thailand and Vietnam. Tokyo, however, seeks to keep most of this rice away from Japanese consumers (perhaps fearing a realization that the taste of foreign indica rice is not so bad, and a bargain compared to the $3,900 per ton for locally-produced short-grain varieties of japonica rice). But under WTO rules, the government cannot re-export the rice, except in relatively limited quantities as grant aid. So the Japanese government simply stores its imported rice until the quality deteriorates to the point that it is suitable only as livestock feed and sells it to domestic livestock operators. Last year about 400,000 tons of rice were disposed of in this manner – at a huge budget loss, and displacing an equal quantity of corn exports from the U.S., thus displeasing another constituency, the U.S. corn growers.

Japan currently has over 1.5 million tons of this rice in storage, roughly 900,000 tons of U.S. medium-grain rice and 600,000 tons of long-grain rice from Thailand and Vietnam. Most of this rice is in good condition, and is incurring large storage charges. Japan should be very happy to dispose of this rice to the world market, but it cannot do so without U.S. acquiescence. (Technically, Thailand and Vietnam also need to give approval for rice supplies originally imported from their countries to be released to world markets.)

U.S. leadership was needed, and forthcoming, but not at the G-8 Summit

The U.S. was reluctant to take the lead in giving Japan permission to re-export its WTO rice, out of fear of potential political repercussions from the U.S. rice industry. Re-exporting the rice from Japan would mean additional competition for U.S. rice exports. But at the moment, there is no competition — that is precisely the problem. The rice in Japan is needed immediately. By the time the next rice harvest in California is available for export late in 2008, the Japanese rice could avert a crisis, but the world market will still need every ton available. It is even in the longer-run interests of U.S. rice growers to prevent this crisis, as the inevitable result of continued high prices will be energetic, but inefficient, self-sufficiency programs in countries that import rice. As a result the U.S. rice export market could actually shrink.

The simplest mechanism to stop the crisis has the U.S. authorize Japan to sell its surplus rice stocks directly to the world market at a price that covers its acquisition and storage costs – probably below $600 per ton, to whichever importer wants to buy. Once this happened, the Philippines was at the front of the line, and quickly arranged to buy 300,000 tons of the Japanese stocks. But other countries have urgent import needs as well, and no additional supplies have been forthcoming. It is important to realize that this additional rice does not “solve” the world’s rice problem—rice at $600 per ton is still a major burden for the poor – but it has the potential to prick the speculative rice price bubble. Indeed, immediately after the announcement of the Japan-Philippines deal, world rice prices fell by $200 a ton over a week.

An alternative, perhaps more politically attractive, mechanism, was also open to Japan at the G8 Summit. It had U.S. approval to donate substantial quantities of the Japanese rice to the World Food Program (WFP), which is actively appealing for additional food aid supplies. The WFP needs at least 450,000 tons of rice for its regular operations – much more will be needed this year because of the disaster in Myanmar. Instead, Japan chose to offer additional funding for food aid, but no actual food supplies. At no time during the G8 Summit did the US pressure Japan to release more of its rice stocks to either the WFP or directly to the world rice market.

A grand gesture ahead of Japan’s G8 Summit? Not!

As it prepared to take the world stage as host of the G8 Summit, it seemed like a golden opportunity for the Japanese government to offer the rice as food aid directly to interested parties and finance the donations from its own budget as humanitarian assistance. With Myanmar reeling from the aftermath of Cyclone Nargis, the WFP’s proposed budget will clearly be inadequate. There was an attractive headline here: “Japan steps in to solve the world rice crisis.” The timing could not have been better, as Japan prepared to host the G8 Summit in Hokkaido in early July. It turns out to have been a missed opportunity.

The roots of the rice crisis

Why is there a world rice crisis at all? There is no single reason, but panic and hoarding are playing a big role. World rice production in 2007 was at an all-time high, with forecasts for 2008 to set another record. The world’s rice consumers have not suddenly started eating more rice. World trade has not collapsed – the volume of exports in the first four months of 2008 was about 20 percent higher than in the same period in 2007. And world rice stocks, excluding those held by China, have been steady the past five years. These trends do not look like an impending crisis, and yet world rice prices have exploded.

And it is not just the international market that is in crisis. From October, 2007 to March, 2008, domestic rice prices increased by 38 percent in Bangladesh, 18 percent in India, and more than 30 percent in the Philippines. These are very large increases for poor people who depend on a single staple food for the bulk of their caloric intake, and typically spend 20 to 40 percent of their income on this one commodity alone. More than 3 billion people depend on rice for their daily food and half of these are very poor. Rice prices approaching $400 a ton meant a meager existence. Rice prices at $1,100 a ton mean starvation. If there is plenty of rice in the world, why have prices exploded?

The world rice crisis has crept up on the United States, focused as we are on the ethanol debate and the high price for bread and gasoline. The U.S. is a major exporter of rice—more than 3 million tons per year, placing U.S. fourth in the export ranks behind Thailand, India and Vietnam. In those countries, and in major importers such as the Philippines and a number of countries in Africa, rice is a matter of life and death. In the U.S., it was national headline news only briefly when Costco and Sam’s Club restricted the number of bags of rice individual consumers could purchase.

Rice is a very different commodity from corn and wheat. Corn is the ubiquitous “multi-end-use” commodity, providing tortillas and corn meal for direct human consumption, high-quality feed stuffs for livestock, high-fructose corn syrup as a basic sweetener for the processed food industry, and now ethanol for fuel. Wheat also has multiple end uses, although only the Europeans use much for livestock feed. Rice is the quintessential “staff of life.” Nearly half the world’s population depends on it as their daily food—over 3 billion people get a third of their calories or more from rice each day. Little rice is fed to livestock and none is used for bio-fuel production (unless the proposal by the Japanese Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry to use its imported rice stocks as raw material for bio-fuel production is actually implemented).

Rice prices have been rising steadily on world markets since 2003. The underlying factors behind this trend in recent years are similar to those pushing up other food prices. Four basic drivers seem to stimulate rapid growth in demand for food commodities: first, rising living standards in China, India and other rapidly growing developing countries, which lead to increased demand for livestock products and the feedstuffs to produce them; second, stimulus from mandates for corn-based ethanol in the United States and the ripple effects beyond the corn economy that are stimulated by inter-commodity linkages; third, the rapid depreciation of the US dollar against the Euro and a number of other important currencies, which drives up the price of commodities priced in US dollars; and finally, massive speculation from new financial players searching for better returns than in stocks or real estate. Underneath all of these demand drivers is the high price of petroleum and other fossil fuels.

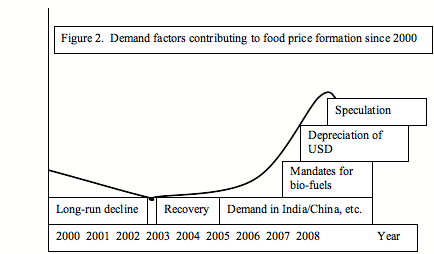

Figure 2 shows an impressionistic attribution of the four demand factors causing the recent run-up in food commodity prices. The figure also shows the recent component of the “normal” long-run decline in food prices that has been experienced over the past two centuries or so and a modest recovery from the lows reached in the early 2000’s. However, the surge in food prices that has attracted so much attention did not start until 2005 or so, depending on the commodity. Substantial speculative investments in food commodities seem to have started only in mid-2007, when heavy speculation from financial investors with little understanding of food commodities played an important role in propelling non-rice prices higher. Such speculation played a less direct role in driving world rice prices up, although speculative activity on rice futures markets in Chicago and Bangkok exploded in February, 2008 and remained high until rice prices peaked in April.

For some food commodities, especially wheat, there have also been significant supply shocks from drought and disease. Normally these would cause only modest increases in price, with supplies from stocks and a pattern of year-round production in the Northern and Southern hemispheres dampening upward movements. But wheat stocks were at historic lows even before the bad crops rippled around the world in 2007 and the spike in wheat prices has been dramatic. The recovery of Australia’s wheat crop, currently being harvested, has caused a significant decline in wheat prices since early April.

Panic and hoarding

Thus the trebling in rice prices has been driven to a greater degree than other commodities by panic and hoarding. These were precipitated by sudden export restrictions in India, which were stimulated by events in other commodity markets, especially wheat, not from local shortages. (Facing a parliamentary election in May, 2009, the Indian government did not want to face further criticism over additional wheat imports – thus rice exports needed to be curtailed to maintain supplies for the Public Food Distribution Scheme.) These export restrictions spread to other suppliers and led to urgent efforts by rice importing countries to secure supplies – at any price – in a thin global market. It is no accident that most of these countries face elections, and food price inflation is extremely unpopular. Rice has returned as the “political commodity,” even in relatively affluent Asia. The result: the extraordinary price rises we have seen in recent months, even though the underlying fundamentals support only modest price increases

From this perspective, the current crisis can be seen as a result of the renewed tension between rice as an economic commodity traded on world markets and its role as a political commodity that influences the fate of poor farmers and consumers, and, consequently, political regimes. Rice prices are the barometer of this tension, and any sign that rice markets are about to spiral out of control leads to understandable behavior on the part of farmers, consumers, traders and governments: store more rice.

The inevitable result of such hoarding is a spiral in rice prices, the very thing that all market participants feared. The only way to break these rocketing prices is to convince market participants that adequate supplies are forthcoming, quickly and reliably. The response is then for prices to fall immediately and sharply when new (and unexpected) supplies hit the market. Pricking the rice price bubble in this kind of market turned out to be possible: the Japanese offer of 300,000 tons of its WTO rice to the Philippines dropped rice prices from more than $1,100 per ton to about $800 per ton by June, but the opportunity to build on that momentum and drive rice prices down further, to perhaps half of the level seen in April, was lost. Remember, even rice at $500-$600 per ton is too expensive for the world’s poor.

China’s Role: Olympic Rice

In addition to the release of Japan’s rice stocks, China could get some badly needed good publicity by taking a leadership role in this crisis. Beijing is holding stocks that are the equivalent of at least 4 months of domestic consumption. China could easily afford to double last year’s exports of almost 1.4 MMT with no repercussions on its own inflation rate. Certainly, Chinese rice traders would like the opportunity to sell some of their stocks at more than double the price they paid to acquire them. It is worth noting that China has helped stabilize the world rice market before: during the three years from 1973 to 1975, during the worst rice crisis ever, mainland China had net exports of 7.1 million tons, compared to just 2.8 million for Thailand. On either side of the crisis, i.e. 1972 and 1976, Thailand exported more than China. Thus, by boosting exports, China played a major role in stabilizing the world market at that time.

Alternatively, Beijing could launch its own food aid program to help the world’s poor – they could call it “Olympic Rice” and make their first donation to Myanmar. This rice could be shipped overland from China, avoiding the logistical nightmare caused by the sinking of 70 ships in Rangoon River during the typhoon. Word from senior Chinese policy analysts is that such a decision could only come at the “very highest level.” Some subtle behind-the-scenes U.S. diplomacy could play a positive role here, although a more aggressive supply offer from Japan might be even more helpful in stimulating the Chinese to take action. These two countries compete on the global political stage as well as in its markets.

Beyond the immediate crisis, investment in agriculture generally and rice, in particular, has suffered over the last two decades, and hundreds of millions of dollars of new funding is needed annually. But the payoff from those long-overdue investments in irrigation infrastructure, plant breeding, and post-harvest losses will only be realized over the medium- and long-term. What’s needed now is a renewed surge of supplies to keep the speculative bubble from re-inflating and to reassure anxious countries and poor people around the world that there is indeed enough rice for everybody.

What did Japan do?

This is Prime Minister Fukuda’s (lightly edited) description of the event:

The G8 Hokkaido Toyako Summit, which began on July 7 — the day of Tanabata, the

Star Festival — ended successfully the day before yesterday without major incident or trouble. This was a tribute to the cooperation of the people of Hokkaido, the security personnel, the volunteers, and many other people. I would like to take this opportunity to extend to everyone involved my deepest appreciation for their support.This year’s Summit was extremely important and drew a high level of interest from around the world, to an even greater degree than recent ones.

The reason for this was because this Summit took place at a time when global challenges such as ongoing global warming, soaring oil and food prices, and tension in financial markets are having a great impact on the everyday lives of people very close to home.

Addressing these issues, the leaders gathered around one table engaged in serious and candid discussions — which, at times, got heated — day and night over three days, producing numerous results.

First, we agreed to seek to adopt as a global target the long-term goal — which, at last year’s Summit, the leaders went no further than agreeing to “consider seriously” — of at least a 50% reduction of global emissions of greenhouse gases (GHG) by 2050. This, needless to say, is based on the premise that the G8 including the US agree on this goal.

We also discussed actively the roles of each country in responding to soaring oil and food prices that have hit family budgets and have become a matter of life or death in the world’s poorer countries.

On oil issues, the leaders agreed to accelerate efforts to have oil production increased, and to conserve energy and introduce new sources of energy. We also agreed to ensure that more detailed inventory information is made available and to strengthen

supervisory frameworks for the futures markets, in order to avoid financial markets having a detrimental impact on prices.On food issues, we decided to further strengthen support for the efforts by developing countries to step up their agricultural production and called for the removal of export

restrictions, as well as for the release of food stocks, as emergency measures.In addition to the leaders of the G8 nations, Japan invited to this year’s Summit the leaders of 16 other countries, including China and India, and the representatives of five international organizations. We carried out frank exchanges of opinions over many

hours with a view to reaching resolutions on the important issues that the world is facing.It is only natural that different countries have different stances and opinions. That said, issues we are facing now are global issues that no one country or even one group can resolve alone. The leaders all acknowledged that a concrete resolution can only be

realized when we overcome our differences, and we expressed to the world our firm resolve to move forward in tackling these issues together.While serving as Chair of this year’s Summit, I became keenly aware of the weight of the world’s expectations for Japan’s contributions to the endeavors to resolve various global issues, including global environmental issues. With the aim of Japan being an indispensable nation for the world, and a nation that its people can be proud of

internationally, we will continue to move forward, step by step, together with the people.

With such “bold action” from Japan on such an urgent issue, where it had the power to act decisively in the interests of resolving the world rice crisis, it is no wonder that commentators asked “where is Japan” as the G-8 leaders gathered. Sad. Japan missed an extraordinary opportunity to exert leadership at the summit, choosing instead lip service. It is not too late, however, for Japan to take advantage of the opportunity to lead the world toward resolution of the immediate rice crisis.

Notes

[1] I would like to thank Tom Slayton, former editor of “The Rice Trader” and now Visiting Fellow at the Center for Global Development, for continuing conversations on these topics over the past several months.

[2] Thai 100% B, FOB Bangkok

C. Peter Timmer is a visiting professor with the Program on Food Security and Environment, Stanford University, and non-resident fellow with the Center for Global Development, Washington, DC. He can be contacted at [email protected].

He wrote this article for Japan Focus. Posted at July 13, 2008.