Oceans Unbounded: Transversing Asia across “Area Studies”

Barbara Watson Andaya

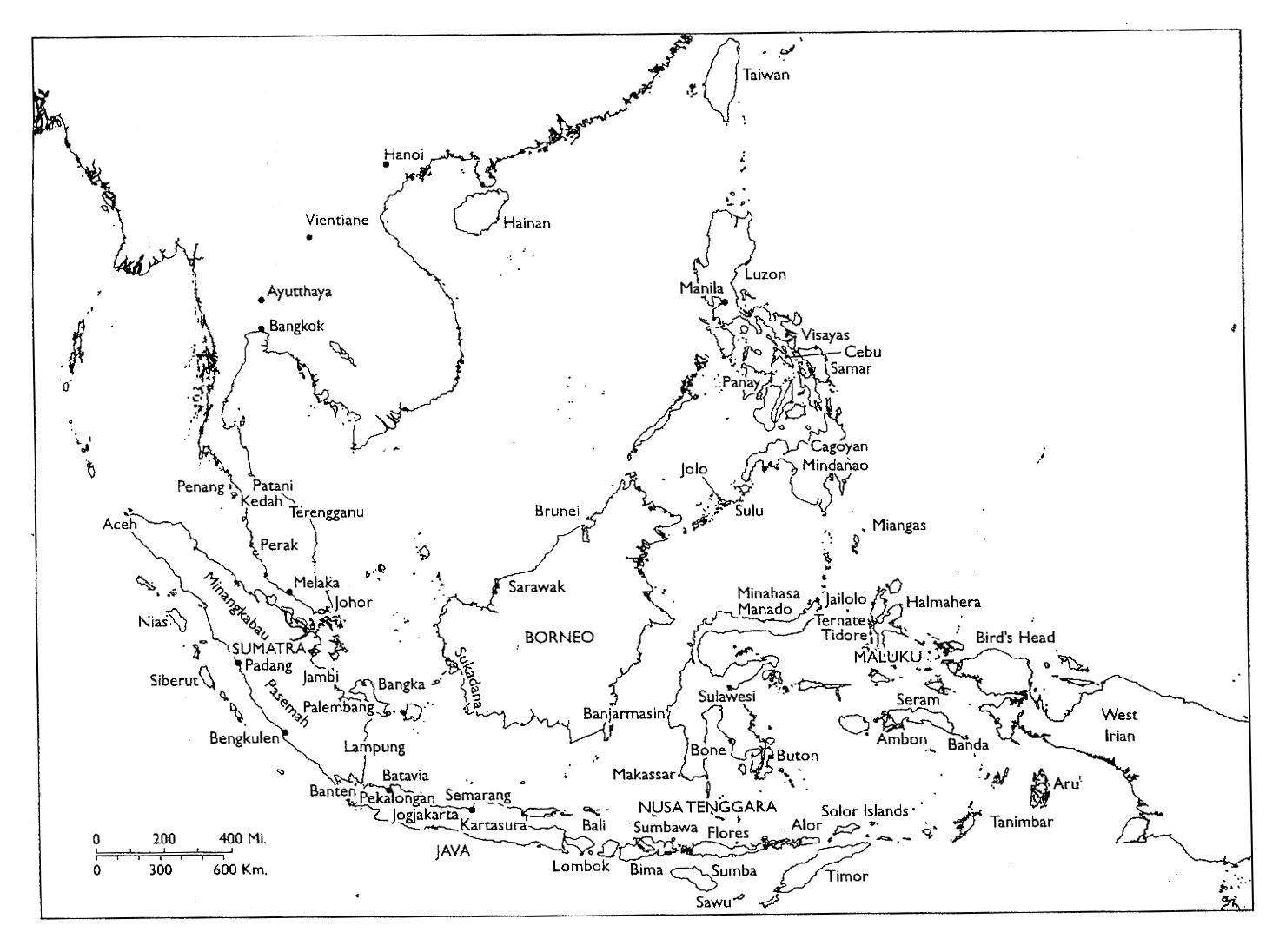

Recent endorsements of maritime history as an integral part of world history should be central in any attempt to transverse the academic divides separating the study of “South”, “East” and “Southeast” Asia (AHA Forum. 2006; Buschmann 2005). Nonetheless, envisaging an interconnected maritime

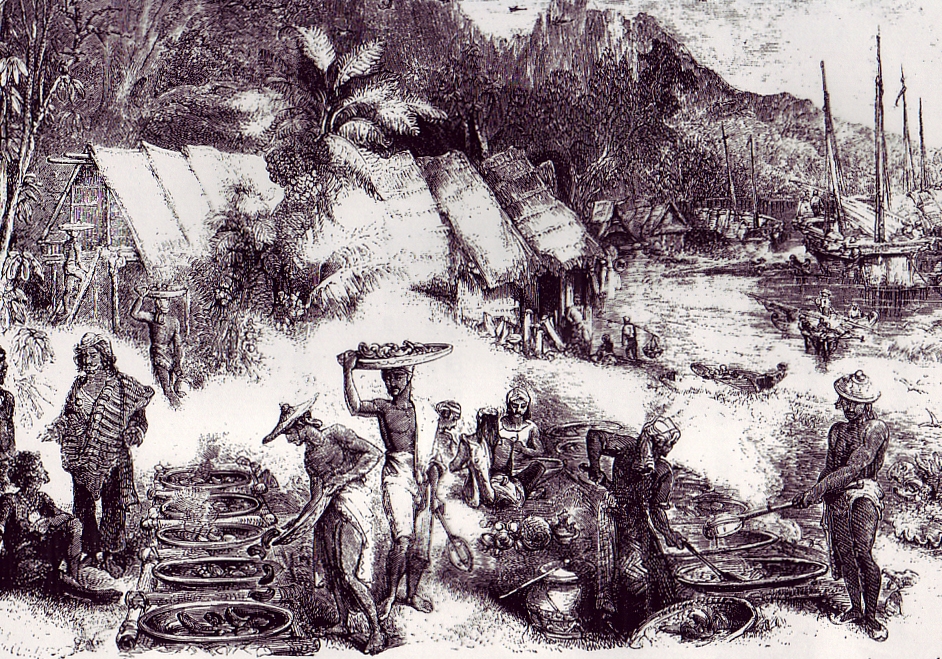

In modern times, when long-distance ocean travel is normally envisaged in terms of a holiday cruise, it is difficult to imagine daily existence among the communities of boat dwellers who once occupied an important economic niche in

Orang Laut houseboat,

Orang Laut woman preparing food,

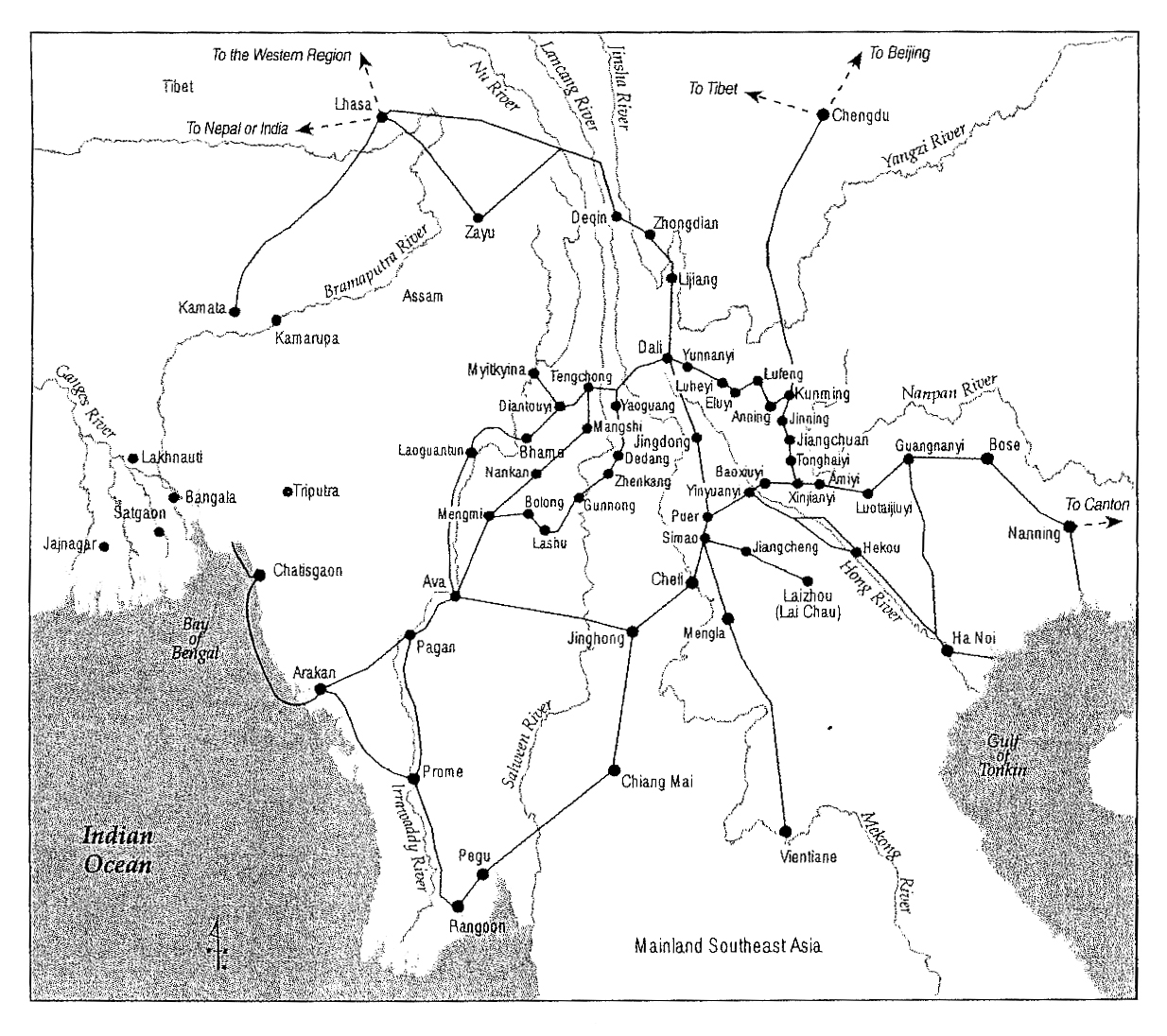

Though now rarely attempted, the possibility of cross-cultural comparisons among such sea-oriented cultures opens up interesting potentials for research. For instance, the concept of compass coordinates is not necessarily congruent with the indigenous knowledge of non-Western societies; the spatial orientation of peoples who spend most of their time at sea has therefore been a topic of considerable interest for specialists in Indonesia and the Pacific. It might be illuminating to ask whether directions such as north and south are related to “up” and “down” among sea-going communities in other areas of coastal Asia as they are in the huge Austronesian linguistic family that covers most of the Pacific and island Southeast Asia. (Blust 1997, pp. 38, 48; Adelaar 1997, pp. 53-81; Sather 1997, p. 93). Let me provide a visual example from the Galela people of Halmahera, in eastern Indonesia. The map shown here, drawn by a Japanese scholar, represents Halamahera and the surrounding area upside down because according to the Galela orientation system, which is related to the monsoon winds and a land-sea axis, “up” lies in a southerly direction, and “down” is to the north (Yoshida 1980, pp. 36-37).

Galela perspective on the world (Yoshida 1980: 36)

The inherited vigilance of societies whose existence is closely calibrated with the rhythms of the sea, and who maintain an ability to read nature’s portents, was dramatically demonstrated nearly two years ago, when a terrible tsunami devastated so much of the area around the Indian Ocean. It was reported that isolated groups on the Andaman and

Relief from

A shift in orientation is not necessarily an easy task, for the polities and governments whose narratives dominate historiography have rarely seen the oceans as an integral part of their territorial domain. More frequently, the sea is regarded as a boundary, separating land inhabitants from other land inhabitants. As John of Gaunt proclaimed in Shakespeare’s Richard II, the “silver sea” served

Even as representatives of land-based kingdoms took to the sea with the goal of reaching places only dimly imagined, the sheer immensity of the earth’s oceans was daunting; after all, they cover 70.8 percent of the earth’s surface. In these ventures the trepidation aroused in contemplating the unknown could be allayed through explanation and classification that made the unfamiliar imaginable. In the tenth century, for instance, the geographer Al-Muqaddasi affirmed that “the realm of Islam” was encircled by just one ocean “and that this is known to everyone who sails,” but he also acknowledged that Muslim treatises often spoke of three, five, or eight seas (Chaudhuri 1985, p. 4; Collins 1974, pp.148-64; see also Lewis 1999). On the other side of the world

Ultimately, however, it was European cartography that identified and named the world’s oceans as we know them today– the Atlantic, the Arctic, the Indian, the Pacific and, in 2000, the Southern Ocean – with boundaries created when necessary; in the Southern Hemisphere, for instance, the Atlantic is separated from the Pacific by an artificial line drawn from Cape Horn to Antarctica. Even so, the human capacity for categorization is indefatigable, and within these five oceans the International Hydrographic Bureau currently identifies as many as fifty-four different seas.

To a considerable degree this desire for categorization, like national borders on the land, has created boundaries and subsets for academic inquiry. Several universities maintain Centers of Pacific Studies; we have a center for Arctic Studies in

In Asian Studies the fine detail this focused research can produce is most evident in regard to the

As the geographer Martin Lewis has noted, these divisions of “sea space” do allow for effective communication among people with like interests. There is, however, a danger that our imaginations can be directed “along certain preset pathways . . . that reflect specific cultural and political outlooks” (Lewis 1999, p. 211). In light of this comment, it is interesting to note that

In this context, the uniqueness of

As innumerable studies have shown, one of the most effective means of tracking such connections in early times is through a consideration of trade. It is not enough, however, just to talk about port cities and maritime routes, and to treat the oceans as simply a “transport surface,” a medium by which products and trade goods moved from one place to another. If we accept that explorations of resemblance and divergence may themselves be illuminating, we need to imagine the human reality that initiated and sustained commercial exchanges along ocean pathways. In viewing the seas as a space for creative human activity (Lowe 2003, pp. 121-122; Steinberg 2001, p. 46), we can only wonder at the human ingenuity that developed the sailing technology required to link far-flung areas, and that located and provided much-desired products for distant and unknown consumers. Is it not amazing, for example, that early communities in tropical

Bamboo basket boats,

and fillers such as sawdust, shredded bamboo or cattle dung. Courtesy

University of Hawai‘i Center for Southeast Asian Studies picture archive

Let us take as another example the case of cowry shells. Although the species of cowries used for money (Cypraea moneta) was widely distributed through the Indo-Pacific area, the best come from the Maldives, and it was the commercial production here (breeding shells on palm fronds and other leaf matter lying in shallow water) that supplied Cypraea moneta for most of the world’s trade until the eighteenth century. The tentacles of these operations were far-reaching; in

Cowry trade (Yang 2004. Used with permission)

A third trade item that might pique student interest is the edible holothuria, the sea slug or teripang. Again, tracking the distances covered by what early Europeans called a “repulsive” product requires us to think far beyond area-studies boundaries, and serves, if we need it, as another reminder of the great lengths to which human beings will go to satisfy the demands of commerce. Although teripang occur throughout the world’s oceans – there are in fact about 1200 known species – the greatest diversity and the largest numbers were found among the islands of

Port Essington,

(Macknight 1976, plate 11. Used with permission)

Comparisons of the cultural environments that are enmeshed in these attenuated chains of communication also deserve attention, for it is here that the human dimension most clearly emerges. I can only reiterate that there are interesting possibilities for comparison across

In responding to this comment, I turn to the island-rich environment of insular

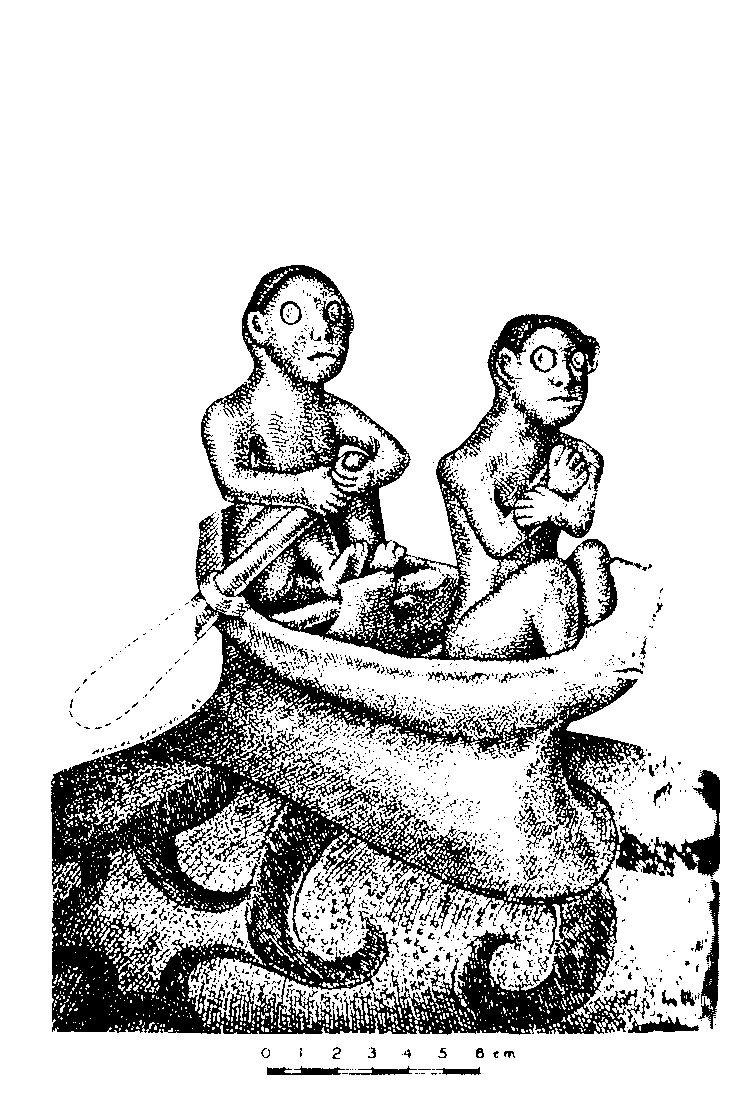

In this context, historians can gain much from conversations with archaeologists. The boat-shaped coffins found throughout this water-connected world, often in locations that face the sea, provide convincing evidence that many early societies thought of the afterlife as a place that would be reached after a voyage across water. Indeed, the words for “boat” and “coffin” are sometimes interchangeable, and from very early times “ships of the dead” are a recurring motif in

Cover of burial jar representing souls sailing

to the afterworld,

(Fox 1970:114)

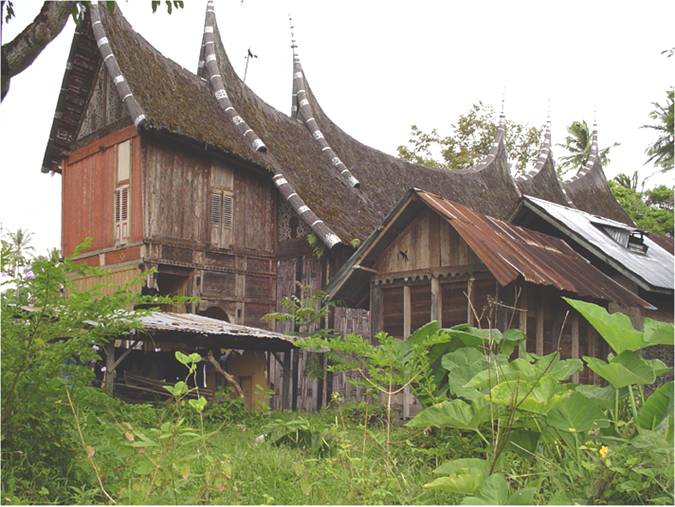

The symbolism that linked the sea to the land is also apparent in the house architecture of numerous Indonesian cultures. Though the derivations of curved and allegedly “boat-shaped” roofs in certain societies have been debated (conversely, the best known are the inland societies of Minangkabau and Toraja), studies of communities in eastern Indonesia, notably between Timor and Tanimbar, persistently employ boat terminology in reference, for instance, to the main posts (“masts”) of the house and the space under the high roofs (“sails”) as well as to other architectural features like the “keel” or “rudder” (de Jonge and van Dijk 1995, pp. 33-34, 74-77; Manguin 1986, pp. 190, 204 n17; Vroklage 1940, pp. 263, 265, 266;). Even when villages are located at some distance from the coast and the economy is based on agriculture rather than seafaring, the association between boats and the human community can still apply, albeit adjusted to an inland environment. In the Sahu (northern

Minangkabau house near Bukkitinggi,

Courtesy of Sara Orel

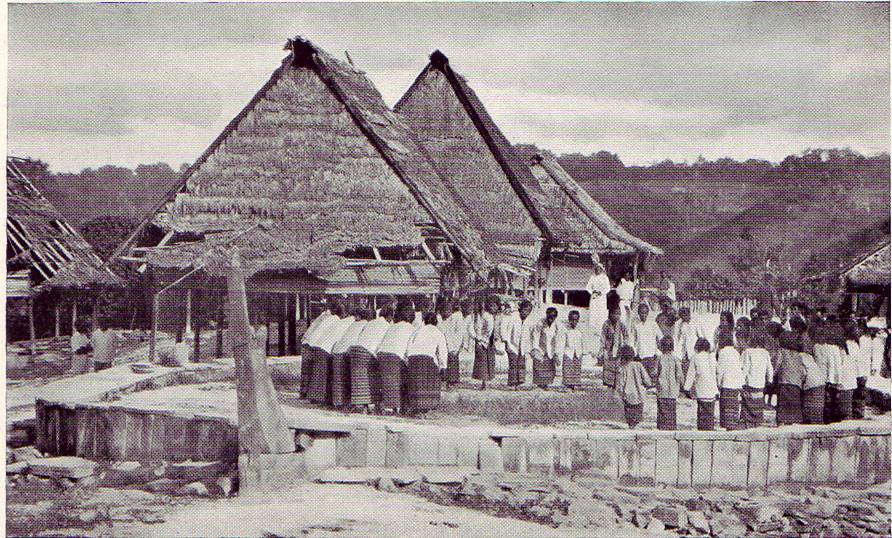

As one might expect, similar metaphors also can be found in regard to community organization. The earliest historical references again come from the

Singing and dancing, people from

set out to renew their alliance with a village on

1980. Courtesy of Susan McKinno

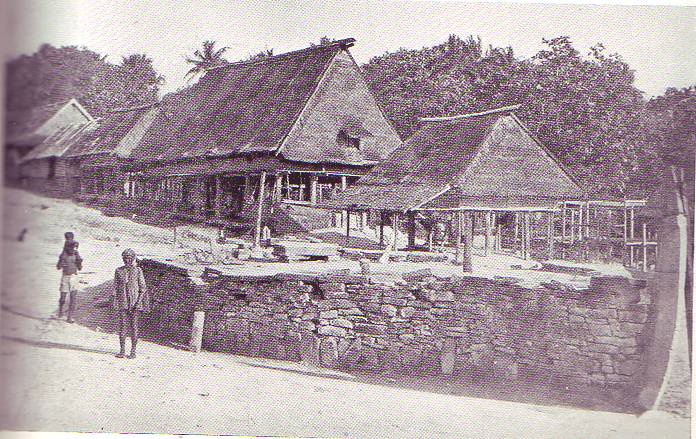

Tanimbar women dance on a stage built

in the form of a boat (from Drabbe, 1940)

Boat-shaped stage, Tanimbar (from Drabbe, 1940).

In eastern

In promoting the comparative framework that lies at the heart of area studies, one obvious approach would see differences and similarities among sea-oriented communities primarily in economic terms, because their livelihood is so clearly reliant on access to the water and its resources. In the words of a female fish trader in Mandar (southwest

The intimate association that correlates the fertility of the sea with the fertility of the land is nicely illustrated in the ritual attached to boatbuilding itself, and of the many examples available I use here Michael Southon’s case study from the

In the constant and finely-tuned interaction between land and sea, seasonal shifts in the patterns of winds and currents were critical to the timing of agricultural as well as maritime activities. In several areas of eastern Indonesian and the western Pacific the swarming of sea worms (nale or palolo) occurs once or twice within a given period of the lunar year and for this reason has traditionally been used as a calendrical marker. In some places one even finds the appearance of the worms – themselves a symbol of fertility – personified in a female spirit, Inya Nale (Ecklund 1977, pp. 4-11; Hoskins 1993, pp. 90-91, 342-44; Mondragón 2004, p. 293). Before their conversion to Islam or Christianity, sculptors in eastern Indonesia represented this sea/land/fertility nexus in statues of the founder-mother (luli), often carved against a tree rising out of a boat, which in turn calls up associations between male-female unity and the womb itself. In combination, the boat, tree and ancestress become a forceful image of fecundity and new birth (de Jonge and van Dijk 1995, pp. 54-55).

Luli carving,

In a different medium and always the work of women, a similar correlation is evident in the Lampung ship-cloths from southern

Example of a Lampung “ship-cloth.”

Courtesy of Bronwen and Garett Solyom

As we place this maritime-oriented world in a larger framework, it is also understandable that the legitimacy of influences from outside is often enhanced through an association with the ocean. Accordingly, legends found throughout

A similar pattern could be tracked in the

In sum, the Southeast Asian examples suggest that the real and symbolic communication between sea and land merits closer attention from those who study the region we term

This brings me to my last point. Although generalizations are always problematic, I follow O.W. Wolters (1999, p. 46) in suggesting that an environment of acceptance and openness to the outside, “a tradition of hospitality,” was generally characteristic of coastal and seagoing communities. The sailor who has a wife in every port may be a cultural cliché, but it had very real significance in a trading environment where a family base was absolutely vital for a merchant to pursue his business. Kinship relations, both real and fictive, were key elements in creating and maintaining the personal relationships that underpinned an economy where land and sea were interdependent. The vignette I use to illustrate this point is one of my favorites. It concerns John Pope, a young Englishman, whose insightful and well-written diary records his experiences as a seventeen-year-old apprentice sailing between

Conclusion

The year 2005 marked the 600th anniversary of the first of Zheng He’s voyages, an impressive vision of a world that could be connected via water. At the same time, these voyages contributed to the goal of knowing, describing and taming the oceans and thus of confirming their conceptual subservience to the land. Today we live in communities that have little appreciation of the importance of the sea in the social and economic lives of early societies. Roads have replaced rivers, airplanes have displaced long-distance ocean travel, and cartographic traditions and the demands of modern states have asserted the supremacy of land-based cultures. In this essay I have tried to make a simple point: Given the physical environment in which most of us operate, we have to work hard to imagine how it might have been in Manguin’s “ship-shape societies.” Yet regardless of whether the goal is to engage students or interact with colleagues, I would argue that the effort is worthwhile. More than twenty years ago Wolters remarked that “the sea provides an obvious geographical framework for discussing possibilities of region-wide [Southeast Asian] historical themes.” He went on to stress, however, the unity of “‘the single ocean’ – the vast expanse of water from the coasts of eastern Africa and Western Asia to the immensely long coastal line of the Indian subcontinent and on to China” (Wolters 1999, pp. 42, 44). The “transocean” standpoint may enable us not merely to work with a larger canvas, but to capture something of the human encounters that underwrite the communication between areas and between peoples. Although there is probably no way we can be what Rhoads Murphey once termed a “complete Asianist” (Murphey 1988), we can do our best to think across the boundaries of disciplines, areas and a presentism that privileges the land. As we work ever harder to bring

Barbara Andaya is Professor of Asian Studies and Director of the Center for Southeast Asian Studies,

This article is a revised version of her presidential address, delivered at the Annual Meeting of the Association for Asian Studies in

Notes

[1] In a similar mode, Paul D’Arcy argues that the oceanic environment transverses the divisions traditionally employed in Pacific Studies by linking Polynesia and Micronesia (D’Arcy 2006: 9). See also Pearson 2006, who argues for a world-wide consideration of littoral societies.

[2] References here are extensive, but for a recent work see Barendse 2002

[3] “The Seas of East Asia,” p. 19; see also Wheeler 2006.

[4] Reference kindly supplied by Anna Nagamine

[5] Currently

Sources

Adelaar, Alexander K. 1997. “An Exploration of Directional Systems in

AHA Forum. 2006. “Oceans of History” American Historical Review 111 (3): 717-780

Ali Haji, Raja. 1982. The Precious Gift: Tuhfat al-Nafis. Ed. and anno. Virginia Matheson and Barbara Watson Andaya.

Andaya, Barbara Watson. 1979. Perak, the Abode of Grace: A Study of an

Andaya, Leonard Y. 1975. The

Anderson, Eugene N. 1972. Essays on South China’s Boat People.

Ballard, Chris, Richard Bradley, Lise Nordenborg Myhre and Meredith Wilson. 2004. “The Ship as a Symbol in the Prehistory of

Barendse, R.J. 2002. The

Barnes, R.H. 1996. Sea Hunters of

Barrow, Chris. 1990. “Environmental Resources.” In Denis Dwyer, ed., Southeast Asia Development: Geographical Perspectives. Harlow: Longman, 78-109.

Bentley, Jerry H., Renate Bridenthal and Kären Wigen. 2007. Seascapes. Maritime Histories, Littoral Cultures, and Transoceanic Exchanges.

Bin Yang. 2004. “Horses, Silver and Cowries:

Blair, Emma and James Alexander Robertson, eds. 1903-9. The Philippine

Blust, Robert. 1997. “Semantic Changes and the Conceptualization of Spatial Relationships in Austronesian Languages.” In Referring to Space: Studies in Austronesian and Papuan Languages, ed. Gunter Senft.

Bose, Sugata. 2006. A Hundred Horizons: The

Braginsky, V.Y. 1975. “Some Remarks on the Structure of the ‘Sya’ir Perahu’ by Hamzah Fansuri.” Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, 131(4): 407-26.

Braginsky, Vladimir. 2004. “The Science of Women and the Jewel: The Synthesis of Tantrism and Sufism in a Corpus of Mystical Texts from Aceh.”

Braudel, Fernand. 2001. Memory and the

Bulley, Anne, ed. 1992. Free Mariner.

Burningham, Nick. 1994. “Notes on the Watercraft of

Buschmann, Rainer F. 2005. Review of Maritime History as World History, ed. Daniel Finamore and Sea Changes: Historicizing the Ocean, ed. Bernhard Klein and Gesa Mackenthun. Journal of World History 16 (1).

Chaudhuri, K.N. 1985. Trade and Civilisation in the

Cho, Hae-Joang, 1989. “Internal Colonisation and the Fate of Female Divers in

Chou, Cynthia. 2003.

Coedès, G. 1968. The Indianized States of

Collins, Basil Anthony. 1974. Al-Muqaddasi: The Man and his Work; with Selected Passages Translated from the Arabic.

Cunliffe, Barry J. 2001. Facing the Ocean: The

D’Arcy, Paul. 2006. The People of the Sea: Environment, Identity and History in

de Jonge, Nico, and Toos van Dijk 1995. Forgotten

Drabbe, P. 1940. Het Leven van den Tanembarees; Ethnografische Studie over het Tanembareesche Volk [The life of the Tanimbarese: An ethnographic study of the Tanimbarese people]

Ecklund, Judith L. 1977. “Sasak Cultural Change, Ritual Change, and the Use of Ritualized Language.”

Emmerson, Donald K. 1980. “The Case for a Maritime Perspective on

Finamore, Daniel, ed.. 2004. “Introduction.” In Maritime History as World History.

Firth, Raymond. 1984. “Roles of Women and Men in a Sea-Fishing Economy.” In The Fishing Culture of the World: Studies in Ethnology, Cultural Ecology and Folklore, ed. Bela Gunda.

Flecker, Michael. 2002. The Archaeological Excavation of the 10th Century Intan Shipwreck. Oxford, England: Archaeopress.

Forest, Alain. 1998. Les missionnaires français au Tonkin et au Siam XVIIe-XVIIIe siècles: Analyse comparée d’un relatif succès et d’un total échec [French missionaries in Tonkin and Siam 17th-18th centuries: A Comparative analysis of relative success and total failure]. 3 Vols. Paris: L’Harmattan.

Fox, Robert B. 1970. The Tabon Caves: Archaeological Explorations and Excavation on Palawan Island, Philippines. Manila: National Museum.

Francis, Peter Jr. 2002.

Gatbonton, Esperanza Bunag. 1979. A Heritage of Saints.

Gittinger, Mattiebelle. 1976. “The Ship Textiles of

Glover, Ian. 1986. Archaeology in

Gonda, J. 1947. Letterkunde van de Indische Archipel [Literature of the Indonesian archipelago].

Hall, Kenneth R., ed. 2006. Maritime Diasporas in the Indian Ocena and East and

Hirth, Friedrich, and W.W. Rockhill, trans., 1911/1966. Chau Ju-Kua: his work on the Chinese and Arab Trade in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries, entitled Chu-fan-chi. Repr.

Hokama Shuzen. 1985/1998. Omoro Soshi.

Hoskins, Janet. 1993. The Play of Time: Kodi Perspectives on Calendars, History and Exchange.

Ivanoff, Jacques. 1997. Moken: Sea-Gypsies of the

Jones, Russell. 1979. “Ten Conversion Myths from

Kalland, Arne. 1995. Fishing Villages in Tokugawa

Klein, Bernhard and Gesa Mackenthun. 2004. Sea Changes: Historicizing the Ocean.

Knappert, Jan. 1999. Mythology and Folklore in

Kumar, Ann and Phil Rose, 2000. “Lexical Evidence for Early Contact between Indonesian Languages and Japanese.” Oceanic Linguistics 39(2):219-55.

Lewis, Martin W. and Kären E. Wigan. 1997. The Myth of Continents: A Critique of Metageography.

Lewis, Martin W. 1999. “Dividing the

Liebner, H.H. 1993. “Remarks about the Terminology of Boatbuilding and Seamanship in some Languages of

Lowe, Celia. 2003. “The Magic of Place: Sama at Sea and on Land in

Macknight, C.C. 1976. The Voyage to Marege’: Macassan Trepangers in

Maier, H.M.J. 1992. “The Malays, the Waves and the

Manguin, Pierre-Yves. 1985. “Sewn-Plank Craft of S.E.

Manguin, Pierre-Yves. 1986. “Shipshape Societies. Boat Symbolism and Political Systems in Insular

McKinnon, Susan. 1988. “Tanimbar Boats.” In

McKinnon, Susan. 1991. From a Shattered Sun: Hierarchy, Gender and

McWilliam, Andrew. 2002. “Timorese Seascapes, perspectives on Customary Marine Tenures in

Mintz, Malcom Warren. 2004. Bikol Dictionary. Diksionariong Bikol. 2 Vols.

Mondragón, Carlos. 2004. “Of Winds,

Murphey, Rhoads. 1988. “Towards the Complete Asianist.” Journal of Asian Studies 47(4):747-55.

Murray, Dian H. 1987. Pirates of the

Needham, Joseph. 1954. Science and Civilisation in

Norr, Kathleen Louis Fordham and James L Norr. 1974. “Environmental and Technical Factors Influencing Power in Work Organizations: Ocean Fishing in Peasant Societies.” Sociology of Work and Occupation 1(2):219-51.

Pawley, Andrew, and

Pearson, Michael N. 2006. “Littoral Society: The Concept and the Problems.” Journal of World History 17 (4): 353-374.

Pearson. M.N. 2003. The

Pham Van Bich. 2004. “When Women go Fishing: Women‘s Work in Vietnamese Fishing Communities.” In Old Challenges, New Strategies: Women, Work and Family in Contemporary

Ptak, R. “Quanzhou: At the Northern Edge of a Southeast Asian ‘

Quirino, Carlos and Mauro Garcia, ed. and trans. 1958. “The Manners, Customs and Beliefs of the Philippine Inhabitants of Long Ago, being Chapters of ‘A Late 16th Century Manila Manuscript’.” Philippine Journal of Science, 87(4):325-449.

Ram, Kalpana. 1989. “The Ideology of Femininity and Women’s Work in a Fishing Community of South India.” In Women, Poverty and Ideology in

Ricklefs, M. C. 1998. The Seen and Unseen Worlds in Java 1726-1749. History Literature and Islam in the Court of Pakubuwana II.

Röder, J. 1939. “Levende oudheden op

Sage, Stephen F. 1992. Ancient

Sather, Clifford. 1997. The Bajau Laut: Adaptation, History, and Fate in a Maritime Fishing Society of South-Eastern

Scott, William. 1994. Barangay: Sixteenth-Century Philippine Culture and Society.

Shakespeare, William. 2003. King Richard II, ed. Andrew Gurr.

Shellabear, W.G. 1885, “Titles and Offices of the Officers of the State of

Solyom, Bronwen, 2004. “Symbols of the Fertile Earth.” HALI: The International Journal of Oriental Carpets and Textiles, no. 137 (November-December): 92–93, 95.

Sopher, David E. 1965. The Sea Nomads: A Study of the Maritime Boat People of

Southon, Michael. 1995. The Navel of the Perahu: Meaning and Values in the Maritime Trading Economy of a

Spyer, Patricia. 2000. The Memory of Trade: Modernity’s Entanglements on an Eastern Indonesian Island.

Steinberg, Philip E. 2001. The Social Construction of the Ocean.

Suarez, Thomas. 1999. Early Mapping of

Teng, Emma Jinhua. 2004.

Toichi Mabuchi. 1974 Ethnology of the Southwestern Pacific: The Ryukyus-Taiwan-Insular

Visser, Leontine. 1989 My Rice Field is my Child: Social and Territorial Aspects of Swidden Cultivation in Sahu,

Volkman, Toby Alice. 1994. “Our Garden is the Sea: Contingency and Improvisation in Mandar Women’s Work.” American Ethnologist 21(3):564-585.

Vroklage, B.A.G. 1940. “De prauw in culturen van

Wade, Geoff. 2004. “Ming

Waterson, Roxana. 1990. The Living House: An Anthropology of Architecture in

Wheeler, Charles. 2006. “Rethinking the Sea in Vietnamese History: Littoral Society in the Integration of Thaun-Quang, Seventeenth-Eighteenth Centuries.” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 37(1):123-55.

Wichienkeeo, Aroonrut and Gehan Wijeyewardene, trans. and ed., 1986. The Laws of King Mangrai (Mangrayathammasart).

Winstedt, Richard and P.E. de Josselin de Jong. 1956. “The Maritime Laws of Malacca”, Journal of the Malaysian Branhc of the Royal Asiatic Society 29 (3): 22-60.

Wolters, O.W. 1999. History, Culture and Region in Southeast Asian Perspectives. Revised Edition.

Yoshida, Shuji. 1980. “Folk Orientation in

Zacot, Francois-Robert. 2002. Peuple nomade de la mer: les Badjos d’Indonesie check accent. [Nomadic sea-people; the Bajau of Indonesia].

Zobel de Ayala, Fernando. 1963. Philippine Religious Imagery. Manila: Ateneo de Manila Press

Zorc, R. David Paul. 1994. “Austronesian Culture History through Reconstructed Vocabulary (an overview).” In Austronesian Terminologies, Continuity and Change, ed. A.K. Pawley and M.D. Ross.