By Asai Motofumi

Anti-Japanese Sentiment at the

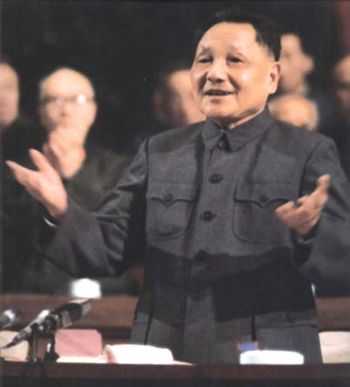

Chinese fans subjected the Japanese team to intense booing at the Asia Cup Games held in

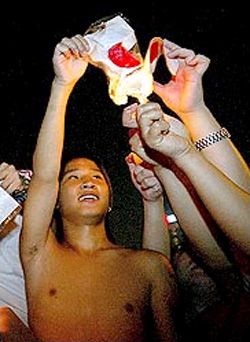

Chinese fans burn Japanese flag at Asia Cup

The impact was not limited to the attention given to the radical actions of the Chinese fans by the Japanese media.

Before analyzing the political circumstances, let us consider the criticism that such actions stem from excessive anti-Japanese content in Chinese education, and the suggestion that if such incidents occur,

The strengthening of nationalistic education in

Memorial and Museum for Nanjing Massacre

To Chinese patriotic education as simply anti-Japanese education is a serious error. I happened to read the Chugoku Shimbun when I visited

When asked, “Will exhibitions at the War of Resistance Memorial Hall stoke anti-Japanese feelings among the youth?” Professor Wang responded, “The purpose of the hall is not to put forth anti-Japanese propaganda. We want Chinese youth to be conscious of how the Chinese nation, with its five thousand years of history, stood up and confronted the suffering and humiliation resulting from the Japanese invasion. When our youth know about that humiliation, they will be inspired to make great progress.”

Inevitably much nationalistic education is related to Japanese aggression in the 1930s and 40s as that was the greatest humiliation that modern

As for the suggestion that if such an event can occur in

Beijing prepares for 2008 Olympics

The riotous actions of Chinese fans deserve serious criticism. But the reports in the Japanese press that give the impression that the entire stadium was filled with Chinese fans engaged in chanting anti-Japanese slogans are ludicrous. Nothing of the sort took place according to postings on the web pages of Japanese fans who saw the match, as well as the impressions conveyed by some of my former students who were present.

Suppose that the rioting was in part a byproduct of nationalistic education. The fact that Chinese fans did not take similar riotous actions at any of the other matches is crucial to understanding the meaning of that event. In short, the actions of Chinese fans should be clearly distinguished from narrow-minded xenophobia.

If

In the worst-case scenario Chinese fans will boo Japanese athletes when they walk onto the field, and only then. Such an event will, without doubt, let the world know that there are tensions in Sino-Japanese relations. Because China-Japan relations have a profound impact not just on

The reasons and the responsibility for worsening China-Japan Relations

The first tangible progress in Sino-Japanese relations after the Second World War can be seen in the policies of reform and opening that took off in earnest under Deng Xiaoping’s leadership. Diplomatic relations were restored in 1972, but with the chaos of the Cultural Revolution it was several more years before the Chinese seriously reassessed China-Japan relations. Economic ties subsequently expanded quite smoothly . In the political realm, however, three problems have dogged Sino-Japanese relations since the reestablishment of formal diplomatic ties. They are the problem of history (the nature of the Japanese war of aggression against

There is also the problem of how lines are drawn around ocean areas to make exclusive territorial claims pertinent to the presence of undersea oil reserves. Recently, there has been much media attention given to the ocean prospecting activities of both

As previously mentioned, conflicts rooted in history have been felt in the controversy surrounding the Japanese government’s 1992 selection of history textbooks . The decision of two Japanese prime ministers (Nakasone Yasuhiro in 1985 and Hashimoto Ryutaro in 1996) to pay their respects at Yasukuni Shrine—where many of the planners of Japan’s war of aggression are honored—makes patently obvious the disregard of history by Japan’s conservative politicians that prevents coming to terms with the unfortunate past. The absence of appropriate understanding of history in

The movement to write a textbook that categorically sanitizes

As for the

Developments in US-China relations cast a long shadow over the

Two significant developments in the US-Japan military alliance have had profound implications for the

“The Legislation to Deal With Military Attacks” seeks to provide rear support in the Afghan war, to dispatch Self-Defense Forces to

Moreover,

Deputy Secretary of State Richard Armitage has stated openly that “Article Nine of the Japanese constitution has become an obstacle in relations within the Japan-America alliance” (

One more noteworthy development is the acceleration of cooperation between the

Clearly there has been progress in cooperation on counter-terrorism between the

Conclusion

Prime Minister Koizumi’s annual visit to Yasukuni Shrine already has damaged Chinese perceptions of

Prime Minister Koizumi at Yasukuni

Shrine

Prime Minister Koizumi would never have visited Yasukuni Shrine at the start of 2004 if he had taken seriously the precariousness of relations with

It should now be clear that we have been not only off the mark in our pointless irritation about the actions of Chinese fans at the Asian Soccer Cup, but also just how irresponsible and reckless our actions have been as far as Japanese relations with China and the Chinese people are concerned. The issue we should concern ourselves with is not Chinese nationalistic sentiment.

Our concern should be to sincerely respond to the three issues of historical memory, the Taiwan Straits problem, and the US-Japan Military alliance in ways that will be ameliorate increasing negative feelings and impressions about

The primary reasons for the deterioration in Japan-China relations can be traced to

Asai Motofumi is a Professor of International Relations at

This is a slightly abbreviated version of an article appeared in Gunshuku (Disarmament), November, 2004, pp. 14-19.

Translation for Japan Focus by Emanuel Pastreich, Assistant Professor, Parkland College, Champaign Illinois.

Posted at