On June 6, 2008, Ainu people across Japan achieved a long-sought goal: they were unanimously granted recognition as an indigenous people by both houses of the Diet with passage of the “Resolution calling for the Recognition of the Ainu People as an Indigenous People of Japan.” Although the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (DRIP) was approved in September 2007 with a “yes” vote from Japan , the government continued to refuse indigenous recognition for Ainu people, citing the absence of an international standard for indigeneity. This June lawmakers forced the government’s hand by adopting the resolution; the Cabinet Secretariat accepted the resolution on the same day. It would seem that the Cabinet Secretariat was the last to realize what international society and indigenous peoples across the world had acknowledged since the 1980s and what Hokkaido governor’s Utari Affairs Council had determined in 1988; that Ainu rightfully belonged to the community of indigenous peoples. Japan ’s plan to host the G8 Summit in Hokkaido during July and much-anticipated global attention were undoubtedly the primary factors in the hasty adoption of the resolution; the Indigenous Peoples Summit in Ainu Mosir created added pressure vis-à-vis grassroots mobilization. As such, the G8 Summit made possible a critical moment – a moment for articulating agency – whereby a new generation of grassroots Ainu leaders were able to launch new initiatives, by harnessing the wave of international attention focused on Hokkaido in early July to articulate a new politics of Ainu indigeneity, which this time had received the imprimatur of Japanese officialdom.

Aside from a small group of Ainu living in Kamchatka, Ainu today reside across Japan, and Hokkaido or Ainu Mosir is considered by most Ainu to be their ancestral territory.[1] “In the past our ancestors lived abundantly on this earth [Hokkaido], unrestrained and freely carrying on their lives, and its an unmistakable fact that we have inherited this vast earth from our ancestors,” Ainu organizer Shimazaki Naomi emphasized.[2] International and domestic attention to indigenous issues was elevated with DRIP’s passage, and the Japanese government anticipated heightened international attention to Ainu issues, with the G8 scheduled for Hokkaido. Expecting that Ainu groups might orchestrate protests in downtown Sapporo or Tokyo thereby exposing the bankruptcy of Japan’s progressive stance on social issues – especially concerning human rights legislation – many have argued the Diet adopted the Resolution to avoid a public shaming before the world community. Legislators were concerned that if Japan, the world’s second largest economy and an aspiring leader among so-called advanced nations, were held to international standards for human rights, it would rank embarrassingly low on the global scale. [3] Their concerns were warranted as Ainu and other minority groups have disparagingly categorized Japan a “third world nation” by human rights standards, and they did organize protest marches straight to the Diet. But these took place in May before the G8 started. Japan ’s reported sensitivity to international opinion and external pressure (gaiatsu) has long been exploited by minority communities to improve human rights inside Japan , and domestic rallying to pass the resolution ahead of the G8 Summit once again supports this argument.

Undoubtedly attention to indigenous issues has been amplified through adoption of DRIP and global civil society has been responding to the indigenous movement in recent years. In Latin America, indigenous peoples have emerged as significant leaders of the new social movements; Bolivians elected an indigenous Aymara leader, Evo Morales, as President in 2006, and Paraguayan President Fernando Lugo recently appointed an indigenous woman as Minister of Indigenous Affairs. In the Commonwealth, Kevin Rudd’s apology to Australia’s “Stolen Generation” (February 2008) has been widely considered a defining moment for initiating a reconciliation process,[4] followed by Steven Harper’s official apology to survivors of Canada’s “Indian Residential Schools” (June 2008),[5] and recently the New Zealand government transferred ownership of 176,000 hectares of forest land to seven Maori tribes.[6]

Just ahead of the G8 Summit, twenty-four indigenous delegates gathered in Hokkaido to discuss climate change and indigenous survival during the Indigenous Peoples Summit (IPS) in Ainu Mosir 2008, from July 1 to 4. “Because the main theme of the Toyako Summit was “environmental issues,” [the Japanese government] created a situation where indigenous Ainu could not be ignored,” Ainu organizer Shimazaki Naomi argued. “We felt that it was critical to make an appeal to the G8 leaders that Ainu are still living here and thriving, and communicate the thoughts of indigenous peoples [during the G8 Summit]. Holding the IPS ahead of the G8 Summit also had a major ripple effect. This impacted not only Ainu people but represents a big step forward for rights reclamation for indigenous people overseas as well.”[7]

The IPS represented an historic moment: it was the first international gathering in the context of a G8 Summit to focus exclusively on indigenous peoples’ responses to climate change solutions and critique the global economic model being promoted by G8 nations. These were also the first G8 meetings to be held since the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (DRIP) was adopted in September 2007.

The G8 host site, Toyako, was located in the heart of Ainu ancestral territory and this summit represented an opportunity for indigenous peoples to urge G8 nations to look beyond economic growth-based models for solutions to the current environmental crisis, to urge non-signatory states [8] to adopt the DRIP, and heed the appeals of indigenous peoples in each nation-state. The G8 Summit provided an occasion for the Japanese government to present Ainu as a “model of man [sic] living in harmony with nature,” according to one media report. [9] While this media report offers a compelling portrait of how Ainu might strategically position themselves to advise visiting G8 delegations on designing eco-friendly policies, to my knowledge the Japanese government displayed no formal interest in Ainu or other indigenous peoples’ sustainable practices during the actual G8. According to Utari Association representatives, several traditionalist kimonos were created by local Ainu women cloth artists to be formally presented to G8 leaders. The Utari Association also requested to perform a kamuynomi ritual blessing ceremony to welcome G8 leaders Ainu-style. Both requests were turned down. The kimonos were placed on display in the Rusutsu Press center and made available for international media to play dress-up. [10] The only case in which Ainu were “presented” in any formal way took place when G8 First Ladies were invited by Hokkaido Governor Takahashi Harumi to don traditional Ainu coats for a group photo, before being whisked off to First Lady Kiyoko’s Japanese tea ceremony.

As the first event of this magnitude to be organized principally by an Ainu-centric Steering Committee – outside government-sanctioned networks of power such as the Ainu Association of Hokkaido [11] – the IPS constitutes a pivotal moment for grassroots and Ainu activism in Japan and the forging of international bonds.[12] The IPS Steering Committee received an unexpected boost from the Japanese Diet when, after twenty years of organized campaigns and 140 years of colonization and assimilation, the Ainu were abruptly recognized as indigenous peoples on June 6. Thanks to the Diet resolution and G8 “summit fever,” the IPS enjoyed international media attention across Europe, Asia, and North America, and was attended by roughly 1800 people, including between 200-250 Ainu. Momentum from the resolution created a mood of celebration and indigenous delegates attending the IPS officially welcomed Ainu into the community of indigenous peoples. Meanwhile, some Ainu leaders were suspicious that this eleventh-hour haste to recognize Ainu indigeneity was another deal brokered for the G8.

The IPS offers one site for critically examining the dynamics of this emergent politics of indigeneity in the Ainu community today. One indicator that the IPS exemplifies a critical moment for Ainu activism, in connection with the indigenous movement globally, is that key IPS organizers plan to formalize this body into a network of global Ainu and indigenous grassroots organizing. Until now, the principal mouthpiece for Ainu rights recovery has been the Ainu Association

In contrast, IPS organizers achieved a degree of indigenous protocol through reintroducing practices such as ukocaranke, or intensive dialogue to work through disagreements. As Shimazaki Naomi put it:

“Holding ukocaranke discussions is a tradition we revived. There are few places inside large Ainu organizations for speaking openly or asserting an opinion. We disgorged our true intentions from the pit of our stomachs and created a spirit of thoroughgoing discussion until all parties reach consensus [inside the Steering Committee]. From these discussions there was much reflection and sometimes emotional pain, but in the end this process led to mutual understanding and trust developed between us. This summit allowed me to understand the importance of forming trust-based relations between generations. Our Indigenous brothers and sisters gave us great encouragement with these words, “We were shocked to see how much the Ainu people have matured, it’s clear that they no longer need us!”[14]

During the IPS itself, with Ainu participants gathered from across Hokkaido and Japan , there was a sense that the Ainu community had begun a process toward a nation-wide dialogue, including communities and stakeholders dispersed across Japan . As one delegate described it, the IPS encapsulated a “watershed moment,” a moment toward “creating a national Ainu organization that includes all Ainu…all Ainu communities in Japan, men and women, old and young, rural and urban.”[15]

A Note on Positionality

I have been involved with the Ainu community in various capacities since 1998. In this article I have written about the IPS in Ainu Mosir from my perspective as a member of the Steering Committee. My initial intention in joining the steering committee was to contribute to the Ainu community by providing resources and information about indigenous campaigns overseas, and help link Ainu with indigenous communities internationally. Anthropologists and archaeologists have been intensely scrutinized in the Ainu community because of unscrupulous research practices and I hoped in part to counterbalance that history through work on the IPS project. [16] As I discuss below, the political and social currents in Japanese society concerning Ainu and indigenous rights shifted dramatically from September 2007-July 2008. Though I sought to avoid factionalism and maintain a neutral position as a supporting member, the IPS itself was controversial within the Ainu community. I was swept up in politicized currents surrounding IPS planning and had difficulty adjusting my position to gain impartiality. In this article I attempt to analyze developments of the previous year and their implications for the ongoing Ainu quest for indigenous rights.

“Ripple effect”: The G8, the Indigenous Peoples Summit, and the Diet Resolution

G8 Summit-related events – including the IPS in Ainu Mosir 2008 – have been identified as the key elements which pushed the Diet toward granting Ainu indigenous recognition. Certainly international and domestic media touted the IPS as a major factor in the Diet Resolution.[17] “The Summit was a great success from many angles,” organizer Kayano Shiro reflected, “however, we had the benefit of timely developments in society and it was the manipulation of those changes to our advantage that made the summit successful. The June 6 Resolution [recognizing Ainu indigeneity] was adopted in the Diet and other actions were preventive measures to protect the reputation of the Japanese government which served as host nation for the G8 Summit. All of these developments were favorable for our Summit.”[18]

However, IPS-related events in fact represent only a small piece of the larger chain of events leading to the resolution. Although Japan had joined 144 other nations to vote in favor of DRIP, [19] the Japanese government persisted in its claim that “no indigenous peoples [as referred to under the declaration] reside in Japan .”[20] Japan ’s “yes” vote came with a caveat: Japan would not recognize “self-determination” if this might harm the sovereignty of existing nation-states, or “collective rights” if these might endanger the human rights of existing citizens. After adopting DRIP, Japanese government representatives distributed clandestine surveys to 100 UN-member states seeking their definitions of indigeneity, local interpretations of self-determination, and policies for “collective human rights.”[21] Whether this was a well-meaning attempt to gather information about other nations’ interpretations of DRIP in domestic contexts, or an attempt to subvert Ainu calls for DRIP implementation, is difficult to assess. The tone of the survey indicated reservation about DRIP’s impact on Japanese sovereignty and hesitation toward the collective rights concept and international interpretations of indigeneity more generally.

Adopting DRIP in September 2007 prompted a series of more aggressive-than-usual initiatives by Ainu organizations across Japan which gained momentum toward July and the opening of the G8 summit. In early 2008, the Tokyo-based Ainu Utari Liaison Group organized a petition drive in downtown Tokyo.[22] In May 2008, they delivered upwards of 6600 signatures to the Prime Minister together with the following requests: 1) that Ainu be recognized as indigenous peoples, 2) that the government issue an official apology to Ainu people, 3) that a nationwide survey of Ainu living conditions be enacted as a precursor to implementing a national policy; 4) that the Ainu Cultural Promotion Act (1997) be reviewed; 5) that a new Ainu/ethnic law be implemented; and 6) that a commission of inquiry be set up to design this Ainu/ethnic law. If the mounting domestic pressure were insufficient, international society added its own support in mid-May. During the Universal Periodic Review of Japan, member states in the UN Human Rights Council’s Working Group recommended the Japanese government initiate dialogue with Ainu and undertake a review of land and other legal rights of Ainu people as steps toward implementing DRIP in Japan . [23]

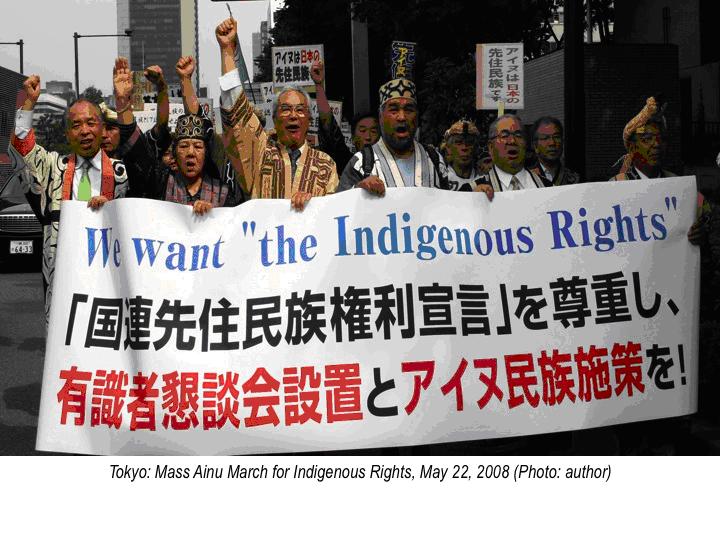

The Ainu Associationalso piloted initiatives that were reminiscent of campaigns to support the proposal for the “Ainu New Law” in 1984, which was substantially revised and adopted as the Ainu Cultural Promotion Act (1997), Japan ’s first multicultural legislation. Focusing initially on Hokkaido legislators and later expanding to national coalition party leaders, the Association orchestrated visits to legislators, recruiting lawmakers to Ainu political rights work. In March 2008, their efforts bore fruit when the “Legislative Coalition to establish Ainu People’s Rights” was established to push for a resolution “recognizing the Ainu’s pride and dignity as indigenous peoples” ahead of the G8 meetings in July. [24] On May 22, the association coordinated a march on the nation’s capital, attended by more than 400 Ainu from across Japan . Adorned in traditional kimonos and waving placards anticipating the G8 environmental theme, “Ainu are kind to the earth” and “the Earth is on loan from our children,” the group marched toward the Diet buildings. Here Ainu Association directors formally read and delivered a formal request for indigenous rights to assembled lawmakers.

One legislator, Suzuki Muneo (New Party Daichi), was especially insistent in pressing for Ainu indigenous rights. Readers may recall Suzuki’s 2002 indictment and arrest for accepting bribes from a Hokkaido lumber company, and connection with perjury, bribery, and bid-rigging with Hokkaido construction companies providing government-sponsored development aid to Russian-held Kurile Islands in the late 1990s. [25] Suzuki, who was thereafter forced out of the Liberal Democratic Party, has refashioned himself as an advocate for the long-suffering Hokkaido economy, and is now championing Ainu issues as well.

Observers have suggested that Suzuki’s political tenacity combined with the Ainu Association’s one-on-one visits to Diet members provided sufficient pressure leading to the Resolution recognizing Ainu indigeneity. From September 2007-July 2008, Suzuki sent a total of sixteen official Diet inquiries pressing the Japanese government to honor DRIP and recognize Ainu as indigenous peoples. This is the same Suzuki who, in 2001 had described Japan as an ethnically homogeneous nation, brushing Ainu aside as “largely assimilated.”[26] Clearly the political winds have shifted. In 2007, his New Party Daichi ran the first Ainu woman candidate on their ticket, [27] and still issued no formal apology for the 2001 statement. [28] Suzuki is nevertheless a career politician and certainly had additional rationales for pushing Ainu indigenous status, namely his interest in liberating Japan from “energy poverty.” The Russian government has indicated a willingness to negotiate with Ainu in returning the southern Kuriles to Ainu as the indigenous inhabitants of the islands. [29] Suzuki argued, therefore, that the Japanese government would gain leverage in bargaining with Russia for transfer of the islands if Ainu are granted status as Japan ’s Indigenous People. By establishing Ainu indigeneity as irrefutable and locating Ainu within the context of Japan the nation-state, Suzuki believes Japan may gain access to these long-disputed islands, and simultaneously reduce its dependence on foreign oil and gas. [30]

On June 6, the electronic display board in the Upper House read “261 In Favor, 0 Against,” and “480 – 0” in the Lower House – unanimous votes passing the Resolution in both houses.[31] However, the Resolution had been significantly revised. The original text placed historical responsibility for Ainu assimilation and colonization on the shoulders of the Japanese government.[32] The revised version masks the linkage between colonial policy and naturalizes the Ainu plight as an unintended casualty of modernity, policies that were indispensable for Japan’s economic and global prowess. While supporters were generally thrilled with the Resolution, many were critical and called it an empty symbolic gesture, especially because its only legal requirement is to set up an Expert Panel.

On July 1 (Day 1 of the IPS), the Cabinet Secretariat announced appointees for the “Expert Meeting on Ainu Policy” (hereafter “Expert Meeting”) established under the Resolution. The Expert Meeting is entrusted with 1) evaluating the situation of Ainu livelihoods and discrimination, 2) evaluating government-sponsored Ainu policy through the present, 3) conducting a review of indigenous policies implemented in other nations, a reference to DRIP, and 4) considering future Ainu policy development, and reporting back to the Cabinet Secretariat in July 2009. Ainu Association Executive Director Kato Tadashi was the only Ainu representative appointed, and while this is a great improvement from the 1995 Expert Meeting on Ainu Affairs with zero Ainu representatives, this limits the diversity of Ainu opinions to one voice. There is room for optimism. During an Ainu Association-sponsored “Ainu Peoples Summit” this July, Tokyo Ainu Liaison members joined with Hokkaido Ainu and Karafuto Ainu descendants to form the first-ever national coalition to issue recommendations to the Expert Meeting. [33] This coalition; however, does not represent the opinions of all Ainu. Although slightly more than half of the Ainu-identified population in Hokkaido are members of the Ainu Association (roughly 12,000), grassroots organizations including the IPS and the non-vocal majority may not be reflected in this coalition. Moreover, in Hokkaido, dialogue about Expert Meeting deliberations has been limited to the Association’s Board of Directors, and thus local members cannot contribute to policy recommendations discussed at the meetings.

In its initial gathering, Expert Meeting members suggested questions of granting indigenous rights to Ainu be shelved during the year-long deliberations, and the government has indicated indigenous rights may not apply to Ainu in any case. In response to an official Parliament inquiry about whether “indigenous peoples” as referred to under DRIP were equivalent to “indigenous peoples” as referred to under the Diet Resolution granting Ainu indigenous status, the government replied, “we are unable to conclude [whether they refer to] the same meaning in this situation.”[34] In other words, the June resolution may simply indicate symbolic “indigeneity” for Ainu.

Ainu Association representatives have criticized the short twelve-month period allotted for devising a national Ainu policy, and have responded with their own strategy: to achieve as many concessions from the government as possible, aside from constitutional amendments. Based on recommendations from the national coalition, Kato is pushing to expand the Utari Taisaku (Utari Welfare Measures) to the national level. Ainu Association officials often refer to the proposed Ainu New Law (1986), noting that only a small percentage of these proposals were included in the CPA (1997), and that they still seek redress on the same issues.[35] Notably, education, pensions for elderly Ainu, and overcoming the gap between Ainu and majority household income are priority items on this agenda. Together with fellow Ainu in Kanto, Hokkaido Ainu also seek a formal apology from the Japanese government for colonialism, assimilation, and institutionalized discrimination, and seek retribution payments through this process. Most Diet legislators are largely ignorant of Ainu history and the Ainu Association is sponsoring study sessions to bring supporting Diet legislators up to speed on historical and current Ainu issues and gain their advocacy to draft an official apology backed by compensation payments.[36] Finally, the Ainu Association will push the government to set up a commission of inquiry with half or more representatives from the Ainu community, to continue discussions on indigenous rights and other issues which emerge when the Expert Meetings have been completed in 2009.

Evaluating the Indigenous Peoples Summit

The IPS forged a space for a new generation of Ainu leaders to articulate their visions of Ainu indigenous politics and highlights Ainu as viable actors in Japanese civil society, but it was not without its weaknesses, nor its critics. I argue the summit serves as a barometer to gauge the position of the Ainu movement internationally and understand key areas for future growth.

From July 1 to 4, twenty-six delegates representing the Americas (Maya Kachikel, Miskito, Nauha, Lakota Sioux, Mohawk, St’at’imc, Cherokee, Comanche and Pueblo); Europe (Saami), the Pacific (Chamoru, Hawai’i, Maori, Yorta Yorta, and Uchinanchu); and Asia (Taiwan, Juma, Igorot, and Ainu) gathered in Biratori and Sapporo to discuss indigenous issues. The main summit program featured delegate position speeches, a keynote address from Victoria Tauli-Corpuz (Chair, United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, hereafter UNPFII) and intercultural exchange, followed by themed workshops focusing on the environment, education, and rights recovery on the second day. On day three, delegates visited Ainu sites in Biratori threatened by development and then traveled to Sapporo for a ritual kamuynomi prayer ceremony, cultural exchange, and an Ainu traditional foods banquet. Two separate appeals, the Nibutani Declaration of Indigenous Peoples and the Appeal from the IPS to the Japanese Government were drafted and then read for approval at the main assembly in Sapporo. [37] Both appeals were adopted by thunderous applause.

In the Appeal to the Japanese Government, delegates addressed future Ainu policy, demanding that: 1) at least half of the designated Experts should represent the Ainu community in the Experts Meeting; 2) an official apology be issued to Ainu people for colonization and earlier Ainu policies; 3) recovery of Ainu indigenous rights as elaborated in DRIP be granted; 4) Ainu language and history be included in Japan’s public education; 5) Ainu representatives be included in southern Kurile negotiations, and 6) the government make strides toward forging “a multiethnic, multicultural” society in Japan. In the Nibutani Declaration, delegates argued that climate change, the global food crisis, high oil prices, increasing global poverty, and escalating violence around the world are all symptoms of growth-based economic models promoted by G8 nations and are therefore fundamentally unsustainable. The declaration urges non-signatory nations to approve DRIP immediately and asks that indigenous peoples be included in future climate talks and assessments to evaluate the impact of climate mitigation measures. Both documents were submitted to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs for distribution to G8 leaders and posted online. With these appeals now circulating globally, IPS organizers have now begun focusing specifically on recommendations to the government-established Expert Meeting in Japan, because this panel will determine future Ainu policy by July 2009. They will also continue to strengthen international ties established through the IPS to hold the Japanese government accountable to Ainu and fellow minority communities across Japan, and to indigenous peoples worldwide.

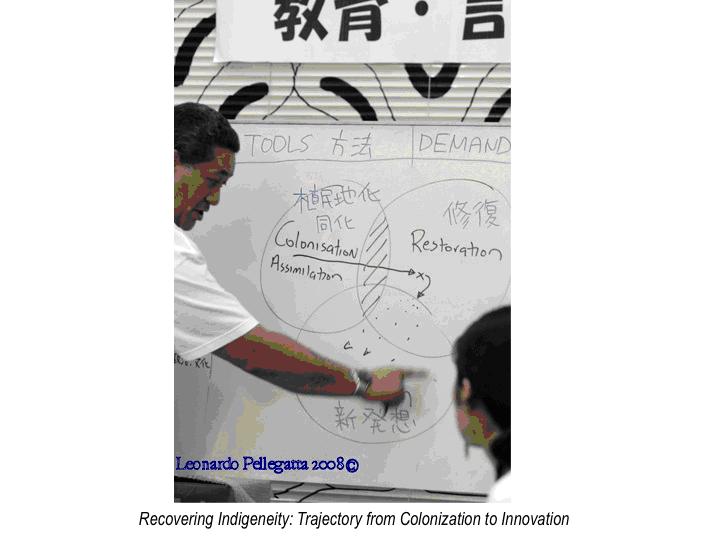

One purpose of the IPS – aside from the political objectives – was to facilitate leadership development and empower young Ainu through the organizing process. Reluctance to engage in power-sharing among Ainu Association elites combined with members’ collective focus on cultural revival since introduction of the Cultural Promotion Act (1997, hereafter CPA), has produced a contingent of Ainu youth who are disillusioned with overemphasis on traditionalism and unresponsive leadership, disengaged from indigenous rights issues, and often shirk the Ainu community. “We hoped to involve many young Ainu” organizer Shimazaki reflected. “Through hosting the summit, the younger generation of Ainu who have lacked opportunities for self-expression until now, were central organizers and have now developed a new network among themselves and are working to expand their global network. It was evident that many Ainu were reawakened to their identity as Ainu, they gained self-confidence, and were able to recover assurance in an Ainu way of living.”

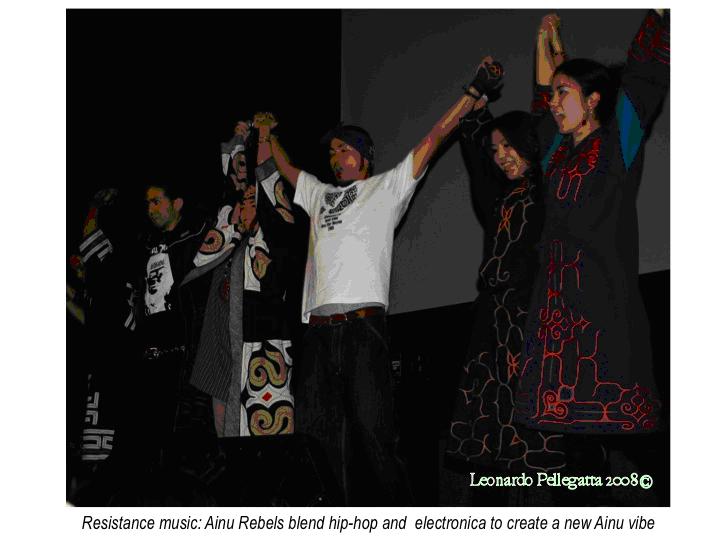

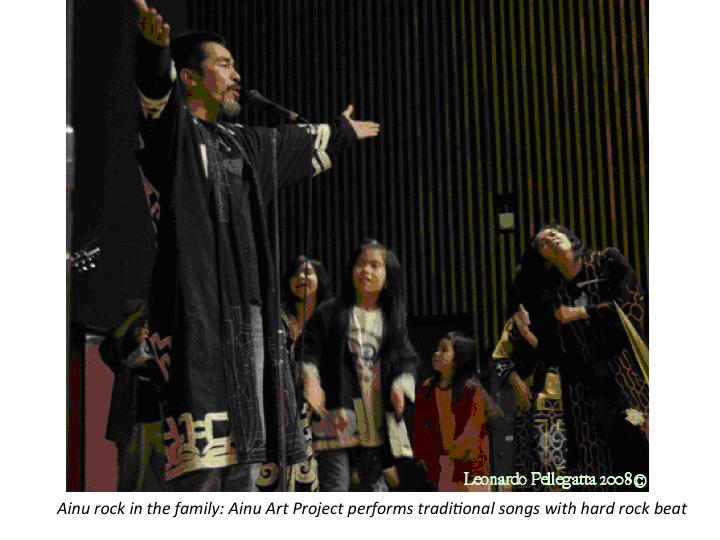

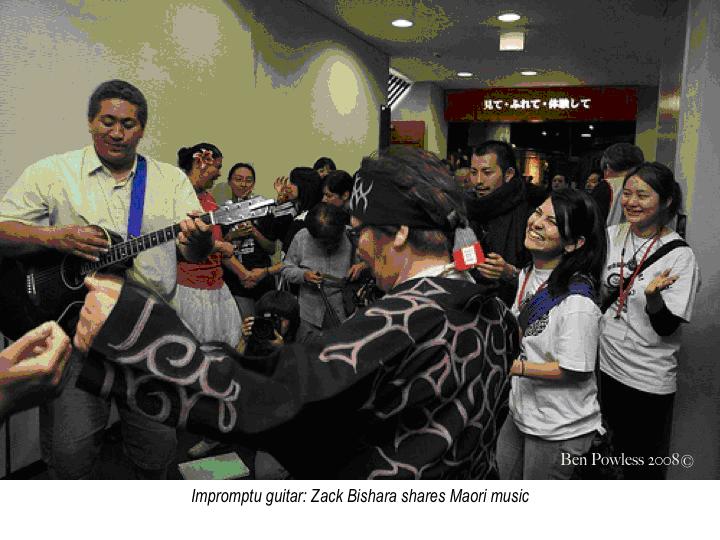

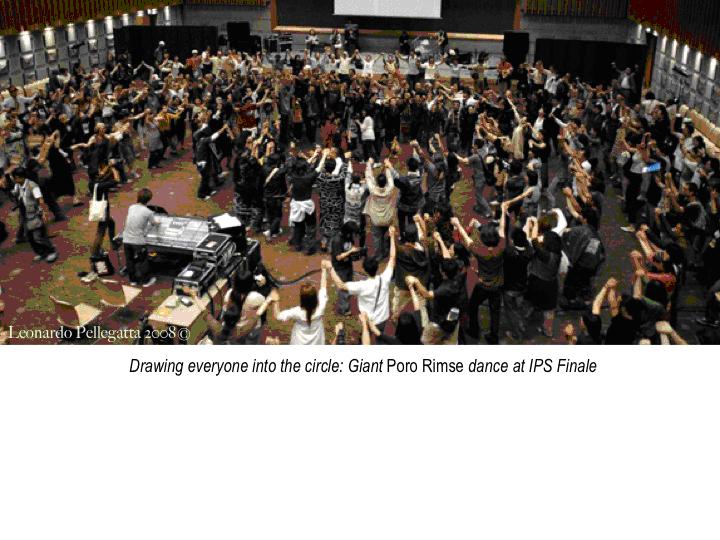

Leaders of up-and-coming Ainu fusion music groups including Ainu Rebels’ Sakai Mina and Sakai Atsushi, and Ainu Art Project’s leader Yuki Koji, formed the core of the steering committee. Youth who do openly identify as Ainu have begun to articulate identities and modes of self-expression which focus on hybridity, blending resistance musical genres such as hip-hop, electronica, reggae, and dub with more traditionalist Ainu music, and adapting dance and other creative forms to convey their newfound pride. The grand finale of the IPS was the Indigenous Music Festival, featuring the widest slate of Ainu artists on one stage in history, including Kano Oki and his Dub Ainu Band, [38] the Marewrew vocal group, Toko Emi, Ainu Art Project, [39] and Ainu Rebels. [40] The music festival offered a space for showcasing contemporary Ainu expression as polyvocal, challenging traditionalist imperatives. In this forum, organized by young Ainu members of the Steering Committee, Ainu youth broke away from the politicized rhetoric of the summit to celebrate ethnic distinctiveness through performance, as an articulation independent of politics.

In planning the Summit, organizers concentrated on three major objectives. The first objective was internationally oriented – to connect Ainu issues and agendas to the indigenous movement internationally and gain from the knowhow of fellow indigenous peoples who had won both political and symbolic historical gains from their respective governments. Secondly, IPS planners hoped to create a network of engaged Ainu persons working outside the usual loci of power, in particular the Ainu Association, and to work on a domestic level for policy change and rights recovery. A third objective was to harness the symbolic capital generated by the G8 itself to urge international leaders to heed indigenous peoples’ concerns, to protect indigenous livelihoods threatened by global warming, and to ensure indigenous participation in future environmental policy-making on a global level.[41]

Objective 1: Globalizing Ainu

The fact that Ainu have now achieved indigenous status enables a reinterpretation of history and the emergence of a new narrative of Japan as a multicultural nation, with historically multiethnic internal populations. Moreover, state-level acknowledgment that Ainu are an indigenous people ultimately exposes Japan’s position as an erstwhile and ongoing colonial occupier in Hokkaido by extension.[42] This implication notwithstanding, the Diet Resolution recognizing Ainu indigenous status did not include direct references to colonialism. Now that Ainu have achieved greater recognition in the eyes of the Japanese state, they can more effectively press for indigenous rights, land restoration, compensation, and other forms of government accommodation, including an official apology for colonialism. As the first ethnic minority to win multicultural legislation (CPA 1997), and achieve indigenous recognition (2008), they also bear responsibility for pushing Japanese society toward greater acceptance of all minorities, both internal historical minorities including Okinawans, Burakumin, Hibakusha, and persons with disability, and immigrant minorities such as Resident Koreans, Nikkei immigrants, and foreign nationals more generally. While a handful of Okinawans are also campaigning for indigenous recognition, they were not included in the Diet Resolution, and only peripherally in the IPS. [43]

Since Ainu organizations began sending delegations to the United Nations Working Group on Indigenous Populations in 1987, the thrust of the Ainu movement has been to pressure the Japanese government to first acknowledge that an Ainu minority exists in Japan (achieved in 1991), and second, to accord recognition that Ainu are indigenous peoples (achieved in 2008). Interest in establishing and strengthening a network between Ainu and indigenous comrades overseas primarily reflects the need for guidance at home, on how to move the Japanese government toward accountability. [44] In both international and domestic contexts, Ainu political elites have focused almost entirely on achieving recognition. This hyper-focus on recognition has eclipsed development of a strategic plan for pursuing indigenous rights beyond becoming “indigenous”; the Resolution has resulted in momentary inertia.

Ainu alignment toward domestic action is in sharp contrast to the focus of IPS indigenous delegates who benefit from treaties and more progressive domestic policies. Many are involved with international organizing and trans-national ventures such as collaboration and leadership training; others serve as leaders of regional indigenous blocks and represent these constituencies in international contexts. They are therefore apprised of the techniques of international law and familiar with the vernacular of international legal-speak. Producing the Nibutani Declaration was an extension of ongoing work on the DRIP for international indigenous leaders.

Producing these appeals involved calling up resources and expertise beyond the range of IP Summit organizers themselves. The Nibutani Declaration, for example, was based on proposals generated from workshop discussions and pre-summit proposals. Program time scheduled for developing this appeal was insufficient, as many delegates noted, and Tauli-Corpuz relied on her own knowledge of international mechanisms and climate change discussions from the UNPFII in May to draft the Nibutani Declaration. The scheduled plan to draft an international declaration based on a single day of negotiations in workshops without any fruitful dialogue in plenary sessions was effectively impossible. The fact that a mere handful of indigenous delegates and Ainu representatives were involved in the process exposes the unfairness of these negotiations and the degree to which an impossible program forced these participants to forego consensus-based indigenous protocol. Meanwhile, on the other side of the room, Ainu representatives feverishly drafted the Ainu Appeal. Here again, the disparity between Ainu representatives’ focus on the local, and international delegates’ focus on the global was thrown into relief. Ainu planners and indigenous delegates praised the finished versions of these two documents although they remained dissatisfied with the composition process. One planner lamented, “The next time we plan an international meeting, we shouldn’t settle with the satisfaction of “all’s well that ends well.” Rather, I think it’s critical to work out a detailed plan and a strategy for obtaining maximum results from the international meeting well in advance of its start.”[45]

Inevitably, language – both language for communication and legal-speak – is a central issue for Ainu in the international arena, and at the IP Summit. The lack of knowledgeable English and Spanish speakers has posed a significant barrier to Ainu networking overseas, leading to a dependency on interpreters who are not always sympathetic to Ainu or indigenous issues. This dependency has its roots in a long history of discrimination manifest in lack of confidence in school-based learning which plays into lower educational achievement than majority Japanese, and limited opportunities for exposure to English as a communicative system. All of these factors have produced a wedge between Ainu persons and possibilities for indigenous-based networking which have been critical for indigenous peoples’ organizing elsewhere.

Summit planners initially hoped to invite foreign-language competent Ainu working overseas to serve as interpreters and showcase their skills through the Summit, but this plan was foiled by insufficient funding. Lack of English and Spanish language ability ultimately served to be a major barrier to full Ainu engagement with the planning process. As one indigenous delegate with an active language revival program noted, English, Spanish, and Japanese are all “colonial languages,” and indigenous peoples need bi- or tri-cultural interpreters who are skilled in one or more of the colonial languages and their own language to facilitate enhanced communication between all parties.[46] This is not now a central issue for Ainu persons as speakers of Ainu language, as all Japanese Ainu are now fluent in Japanese, and those who do speak Ainu as heritage speakers or are self-taught, are not sufficiently fluent in English or other “colonial languages” to negotiate all three linguistic domains. One positive outcome of the IPS is that younger Ainu organizers are now considering study abroad with newfound indigenous comrades overseas.

Objective 2: Expanding the Grassroots to the Nation

Regarding the second goal, to create a grassroots network of Ainu, many Ainu point to the need for power redistribution inside the Ainu Association and without. Insiders charge that the nearly all-male Board of Directors, notoriously cozy with Hokkaido Prefecture and government authority, must make way for a wider network more reflective of the diversity of identity and purpose in today’s movement, not to mention gender and regional differences. The IPS was designed to present an alternative voice on Ainu and indigenous matters, a means toward generating grassroots perspectives to counter Ainu Association hegemony. Despite the obstacles to forging this network, many organizers still argue the summit successfully fomented empowerment among Ainu. “I think we can take pride in the fact that we held the first Indigenous Peoples Summit-named meeting in the host site for the G8 Summit,” organizer Kayano opined. “The fact that we were able to successfully organize an international meeting with our own hands led us Ainu to feel more confident in ourselves. Some members of the Steering Committee achieved remarkable growth through this process. I believe that among fellow Ainu, a feeling of solidarity was born. Through this opportunity, I anticipate that Ainu will achieve greater unity.”[47]

Communicating the IPS’ purpose to Ainu across Japan proved a central hurdle through the final day of the Summit. Since the IPS Committee included both Ainu and non-Ainu members, it was criticized as being dominated by non-Ainu. Working outside official channels was risky because summit organizers lacked the backing of the Ainu Association which is a necessary ingredient for entrée into rural Ainu communities. They were thus unable to promote the IPS widely. Outside urban areas, the Association is the primary “glue” uniting Ainu. In Biratori, the host community for the summit, planners did not engage the community in advance and were unable to recruit logistical support or local participation.

The urban-rural gap was remedied by a creative initiative led by young Ainu planners. In June, three Tokyo Ainu women embarked on a “Caravan Tour” across Hokkaido to promote the IPS. Colonization and assimilation have splintered Ainu communities and now Ainu live scattered across Hokkaido and Japan. Caravan leaders zig-zagged to these communities and plotted their progress in an online blog [48] and through video, which was aired at the IPS. This Caravan Tour provided a context for Tokyo Ainu to connect with Hokkaido Ainu and forge new networks where before there had been separation, silence, and resentment. Their work to connect Ainu across Japan was one of the most productive grassroots efforts to emerge from Summit planning and brought greater numbers of Ainu to the Summit than any other strategy.

Objective 3: Climate in Crisis, Indigenous Peoples, and G8 Responsibility

Taking place just ahead of the Toyako G8 Summit with its climate change centered theme, the IPS sought to highlight environmentally-sound practices embedded in indigenous lifestyles, and to critique the growth-based economic model advocated by industrialized nations. Indigenous communities argue that they have a special mandate to address the global environmental crisis because they are directly dependent on the natural environment for their livelihood, experience immediate consequences when the environment fluctuates, and have observed and experienced global warming-related changes for decades.[49] Mitigation measures now being introduced to combat global warming have also adversely affected indigenous communities in what might be dubbed “neo-energy colonialism.” During the last century, indigenous peoples’ lands were targeted for fossil fuel extraction; now indigenous-managed lands are being targeted for corn, soybean, and oil palm plantations for bioethanol production. [50] Indigenous peoples are experiencing loss of traditional gathering and agricultural lands due to competition with biofuel plantations and hydroelectric dams. [51]

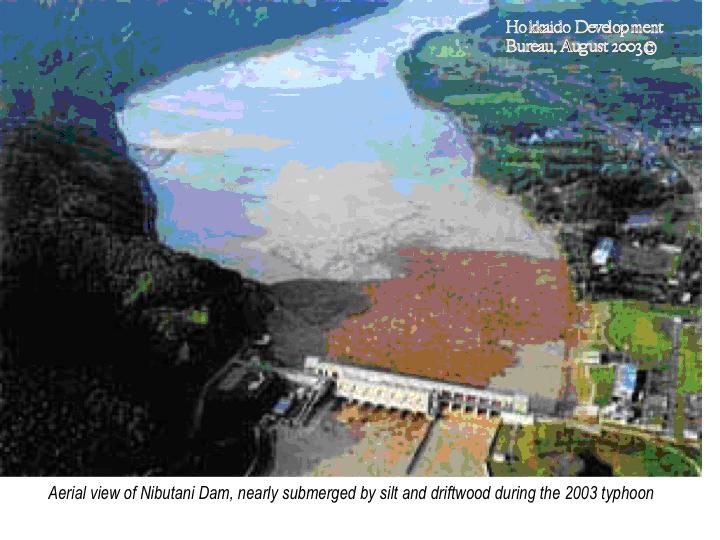

The Ainu community has not been immune to these issues. Hokkaido Ainu were faced with a hydroelectric project, the Nibutani Dam, the subject of a protracted legal battle between two Ainu landowner-farmers and Japan’s Ministry of Construction. [52] The case was launched because construction of the Nibutani Dam would radically transform the landscape of the Saru River, submerge several places of spiritual, economic and cultural import, and destroy several acres of farmland. Although the Ainu plaintiffs won the case through appeals, dam construction had been completed and the court ruled it could not be removed. Ultimately Ainu plaintiffs continued the case to force the court to recognize Ainu as indigenous peoples – a goal achieved in 1997. Ironically, Nibutani Dam has now proven ineffective. During a devastating typhoon in 2003, the dam nearly buckled from a deluge of debris and silt. A second dam scheduled for construction upstream on the Saru River, Biratori Dam, has been rationalized as a panacea to correct the weaknesses of the earlier dam, but opponents argue that it too will fail to meet projected goals and ask that dam construction be stopped.

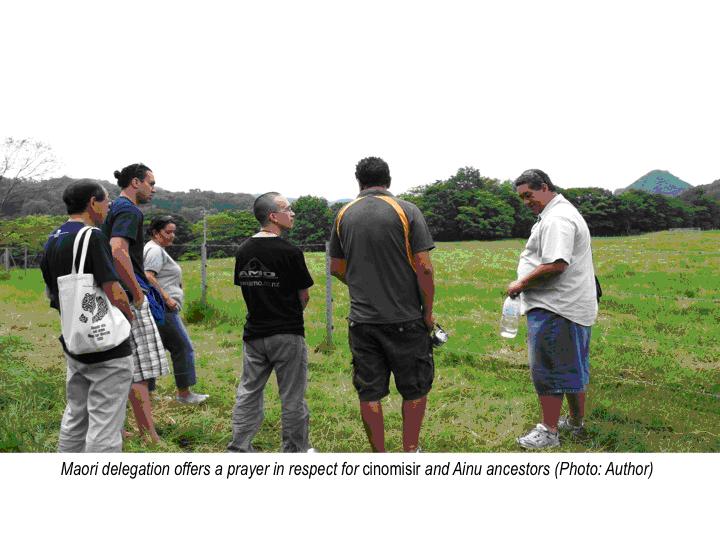

In Biratori, the dam issue has been especially divisive within the Ainu community because many residents see these public works projects as deliverance from a sluggish economy and rural depopulation while a minority is concerned about cultural and environmental sustainability locally. Biratori Dam construction will necessitate submerging three sacred Ainu sites (cinomisir), 17 archaeological sites, and destroy habitat for Ezo Brown bears, an endangered species of falcon, and wild mountain vegetables which have sustained Saru River Ainu communities for centuries. The proposed Biratori Dam was also a focal point of the Environment workshop. During the IPS fieldwork program, a local Ainu elder led a tour of the dam construction site.

Standing before the sacred mountain her grandfather had worshipped, this lifelong resident of Biratori explained her ambivalence about the project. She feels wedged between pressure to support the local economy through dam construction and realization that the natural environment which nourished her community for generations will be forever changed. She mentioned that she likely would not live long enough to see the dam to its completion. Next, indigenous delegate Joan Carling described the Filipino San Roque Dam project, describing how Igorot communities welcomed the development until they lost their homes, farmland, and then began to oppose dam projects.

Indigenous peoples are said to have the “smallest ecological footprints on earth” in greenhouse gas emissions, but will bear the brunt of the ecological damage from failed environmental policy. [53] Currently there are reportedly 370 million indigenous peoples scattered in communities across the globe today many of whom will be deeply affected by climate change; however, indigenous peoples in industrialized nations occupy a more complex position. The majority of IPS delegates came from industrialized nations, yet all continue to practice indigenous life ways in these industrialized nations, and many have abandoned contemporary consumption practices to reinstate traditional economies. They did not elect to be assimilated, and colonization has no doubt wrought tremendous damage to their communities. In their pre-colonial phases each of these cultures incorporated a self-preservation strategy based on respecting natural resource limits without over-harvesting.

As Japanese citizens, Ainu also consume the energy, resources, and cheap commodities being circulated under G8 policy and globalization. As unwitting beneficiaries of Japan’s trade and investment policies across Asia, Ainu are at the same time a colonized people and Japan’s only nationally-recognized indigenous people. As such Ainu occupy an ambivalent and complex position within Japan, within Asia, and among indigenous peoples worldwide.

On the other hand, the largest portion of the world’s 370 million indigenous peoples must cope with the threat of invasive development and the fallout from overdevelopment. There is a palpable sense of urgency that indigenous peoples themselves will be the first “environmental refugees,” or human populations displaced by climate change, unless drastic policy changes are introduced soon. Indigenous peoples have the capacity to choose sustainable practices, choices which have protected 80% of the world’s biodiversity, concentrated in indigenous-held lands. [54] One of the summit’s larger objectives was to force G8 leaders to heed indigenous peoples’ demands for partnership in finding solutions to climate change issues. Indigenous peoples have been largely excluded from global climate change talks until now.[55] In 2009, they will hold an Indigenous Peoples’ Global Summit on Climate Change, and will officially join the Copenhagen global climate talks.[56]

At the same time, indigenous peoples are exercising some degree of strategic essentialism to push an agenda of “traditionalists vs. moderns.”[57] There is a danger in broad brushing all indigenous peoples as “ecologically noble savages,” [58] even if these images are in part self-authored. Effectively, strategic essentialism obscures the actual complexity, fluidity, and hybridity of most indigenous peoples today who have become flexible interpreters of their own cultures, who combine modernist and traditionalist livelihoods, and who, by necessity, have learned to adapt to the shifting political and physical landscapes in their home communities and beyond. This model also masks the realities of urban indigenous peoples who have been displaced from their land, or who live in cities for economic security, by declaring them somehow less indigenous by virtue of their urban-ness. And most importantly, this image does not account for the complex situation facing Ainu, who have been displaced from their land, have been robbed of their connection to the natural sphere where human-deity relations are negotiated, have lost access rights to the raw materials of cultural reproduction, and have been forcibly assimilated to majority Wajin lifestyles.[59] I do not intend to discount the majority of Ainu-identified persons today who trace their involvement to the cultural revival movement which emerged in tandem with but did not necessarily politically align with Ainu ethnic nationalism in the 1960s and 1970s. Even for Ainu cultural revivalists, however, cultural practice is continued in a separate domain from livelihood, which is predominantly aligned with the majority Japanese economy of consumption. A glimpse of the global diversity indigenous peoples represent was in evidence at the IP Summit. Indigenous perspectives spanned the gamut between industrialized and developing nations, land-rich and land-poor, environmentally-engaged and rights-focused, urban and rural, the global South and the global North, and language-intact and language-moribund communities.

Conclusion

As I have described, the IPS was a turning point for the Ainu community and significant for the international indigenous movement as a display of indigenous agency in the face of neoliberal policies advocated by the world’s leading capitalist economies. Nevertheless, it is difficult to evaluate the efficacy of the IPS because there is no clear indication that G8 leaders actually will respond to or act upon the IPS appeals. There were however significant internal gains from the IP Summit. Younger Ainu were able to participate fully without age-based hierarchies which often constrain youth participation in larger Ainu organizations. Perhaps most importantly, planners overcame geographic, political, economic, and mental barriers to build solidarity as an organizing body for the summit. With the strength of this unity as their base, they now hope to transform the IPS organization into a nationwide coalition of Ainu and work toward deepening the international network which emerged from the Summit.

Here I have tried to emphasize the diversity of positions both within the Ainu community, and within the larger indigenous people’s movement. The Ainu movement inside Japan has suffered from prolonged political inertia since passage of the Ainu CPA (1997), although Tokyo Ainu have actively sought an “ethnic law” expanding the scope of Ainu policy beyond the Tsugaru Strait. Since 1987 Ainu Association leaders have pressed the state for indigenous recognition through international fora, and as of June 2008 have finally achieved this goal. Many insiders are wary of the next step, however. Specifically, they cite the crisis of leadership and absence of a long-term strategic plan as the main barriers to future rights recovery for Ainu people. On the whole most self-identified Ainu embrace generalized ideas about reparations for colonization and institutionalized discrimination; yet few are acquainted with how to articulate these in the language of indigenous rights, or with how the DRIP may serve their specific needs. The non-democratic and government-reliant structure of the Ainu Association has fostered blind dependence on leadership and overall apathy concerning rights-work. To counter these tendencies IPS organizers are now planning study sessions to empower Ainu individuals in knowledge and application of the DRIP; they are also forging community-based networks between Ainu and majority Japanese supporters to formulate appeals for submission to the Expert Meeting in Tokyo. To continue the momentum generated by the IPS Ainu groups are now working on spreading their newfound empowerment to the wider Ainu community.

Concerning the IPS, despite my criticism of “native ecology,” I want to recognize the agency of indigenous peoples to choose their own narratives and locate potent symbols to articulate their concerns to the international community in the language of international law. Fundamentally, indigenous peoples’ right to self-determination is ensured by Article 3 of DRIP, and I support unimpeded realization of this right. Yet, not all Ainu or indigenous people may be painted as unapologetic ecologists; they are sandwiched between competing demands of the ideals of modernity, allegiance to ancestral systems, and modernity-in-crisis. The international indigenous community has managed to form an effective global bloc in part through emphasizing commonalities to defend themselves against multinational corporations’ and state-led encroachment into their territories. The threat of climate change and the potential damage to many Pacific Islanders, permafrost dwellers, and countless other communities who do depend on the resiliency of the ecosystem to sustain themselves, is immediate and real. Having the support of the world’s indigenous peoples to pressure nation-states for accountability to their own populations together with other vulnerable populations overseas, is essential for drafting better policy to ensure survival for humans, flora and fauna. Asserting that the eyes of the world are on each of the nation-states mentioned in the Nibutani Declaration is key to regaining not only rights, but also dignity and self-respect – two critical ingredients for survival and adaptation.

Acknowledgements: I would like to thank the Steering Committee of the Indigenous Peoples Summit for encouraging my involvement with and post-summit analysis of the IPS project, and to individual Steering Committee members for sharing their feedback. A special thanks to Richard Siddle, Philip Seaton, and Jeff Gayman for their insightful readings and criticism. This project was supported by a grant from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science and Hokkaido University. Any errors in interpretation are mine.

Posted at Japan Focus on November 30, 2008

Recommended citation: ann-elise lewallen, “ Indigenous at last! Ainu Grassroots Organizing and the Indigenous Peoples Summit in Ainu Mosir” Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, Vol. 48-6-08, November 30, 2008.

|

Article Series Index |

|

|

Alternative Summits, Alternative Perspectives: Beyond the 2008 G8 Summit |

by Philip Seaton |

|

The 2008 Hokkaido-Toyako G8 Summit: neither summit nor plummet |

by Hugo Dobson |

|

Indigenous at last! Ainu Grassroots Organizing and the Indigenous Peoples Summit in Ainu Mosir |

by ann-elise lewallen |

|

by Lukasz Zablonski and Philip Seaton |

|

|

by Philip Seaton |

|

|

Other Resources |

|

Andrew DeWit , The G8 Mirage: The Summit and Japan’s Environmental Policies |

References

[1] Ainu Mosir means the “domain of humans,” in the Ainu language (as opposed to kamuymosir, or the “domain of the gods”) and is currently the most widely-accepted term for Hokkaido. Some Ainu language scholars argue that yawnmosir, or “land country” (as opposed to repunmosir or “ocean country”) is a more fitting name for Hokkaido. Technically there is no overarching term in the Ainu language which refers specifically to Hokkaido, because Ainu historically dwelled in Southern Sakhalin and the Kurile Islands, Hokkaido, and Northern Honshu, and did not conceptualize their terrain using modernist concepts of territory such as the nation-state.

[2] Shimazaki, N. 2008. “ Senju’uminzoku Samitto Ainu Mosir 2008 kara takusareta mono.” In IMADR-JC Tsu’ushin 155.

[3] Imazu Hiroshi (House of Representatives) led a group of non-partisan Hokkaido politicians in launching the “Legislative Coalition to establish Ainu people’s rights” in March 2008.

[4] See Zablonski and Seaton in this special edition of Japan Focus.

[5] United States president elect Barack Obama has suggested that he may consider an official apology to Native Americans for the legacy of discrimination and abusive treatment they have received at the hands of the U.S. government (Obama at Unity Journalists of Color Convention, Chicago: July 27, 2008).

[6] Associated Press. “New Zealand gives Maori tribes forest in largest-ever settlement.” International Herald Tribune, June 25, 2008.

[7] Shimazaki, N. 2008. “Senju’uminzoku Samitto Ainu Mosir 2008 kara takusareta mono.” In IMADR-JC Tsu’ushin 155.

[8] Non-signatory states include Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States; Russia abstained from the DRIP. In the Nibutani Declaration, IPS delegates focused principally on G8 nations, and therefore included Australia and New Zealand only indirectly.

[9] Kuhn, Anthony. “Japan recognizes indigenous group.” All Things Considered, National Public Radio: August 12, 2008 (http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=93540770, Access date: August 13, 2008.)

[10] Personal Communication: Sato Yukio, 25 August 2008.

[11] Membership of the Ainu Association

[12] During the 1989 International Indigenous Peoples Conference, Ainu were not included in the planning process and were involved only tangentially; in the 1993 Nibutani Forum Ainu organizers were centrally involved but lacked local community support; and during the 2005 Biratori-Nibutani Forum local Ainu organizers formed the core of the planning team and enjoyed community support, but Ainu were not involved on a national or global scale.

[13] For a thorough history of the Ainu movement during the 20th century, including a detailed discussion of the Ainu Association, see Siddle, Richard. 1996. Race, resistance and the Ainu of Japan. London; New York: Routledge. x, 269 pp.

[14] Shimazaki, N. 2008. “Senju’uminzoku Samitto Ainu Mosir 2008 kara takusareta mono.” In IMADR-JC Tsu’ushin 155.

[15] IPS Survey response, 28 August 2008.

[16] lewallen, ann-elise. 2007 “Bones of Contention: Negotiating Anthropological Ethics within Fields of Ainu Refusal.” Critical Asian Studies 39 (4): 509-540.

[17] See, for example Azuma, Shoko. 2008. “Culture & More: Ainu come out from obscurity to reclaim rights”. Asahi Shimbun; Foster, Malcolm. 2008. “Indigenous peoples criticize Canada, blame G8 for global warming”. The Sault Star. July 5; Ito, Masami. 2008. “Diet officially declares Ainu indigenous”. Japan Times. June 7; Kambayashi, Takehiko. 2008. “Japan’s Ainu hope new identity leads to more rights”. Christian Science Monitor. June 9; Koike, Masaharu. 2008. “[G8 Toyako Samitto Orutanatibu] senju minzoku samitto Ainu Mosir 2008 Sakai Mina san ni kiku”; Makino, Catherine. 2008. “Ainu people to press demands at G8 Summit”. Inter Press Service News Agency. April 28; Mochida, Takeshi. 2008. Yoyaku mitomerareta Ainu ‘retto no senju minzoku’ ketsugi. In JanJanNews; Onishi, Norimitsu. 2008. “Nibutani Journal: Recognition for a people who faded as Japan grew”. The New York Times. July 3; Pellegatta, Leonardo. 2008. L’altro volto di un summit. ALIAS. 30 August 2008: 6-7; and Takayama, Hideko. 2008. “Japan’s Parliament recognizes Ainu as indigenous people” In Bloomberg.com.

[18] Kayano, Shiro. “Reflections on the Indigenous Peoples Summit in Ainu Mosir 2008.” August 2008.

[19] The final vote for DRIP were 143-4, with 11 abstentions. Negative votes were cast by the CANZAUS states; Canada, the US, Australia, and New Zealand. Votes of abstention were cast by Russia, Azerbaijan, Israel, and Georgia, among others.

[20] Hokkaido Shimbun, September 14, 2007; Indigenous Peoples Summit in Ainu Mosir Guidebook 2008: 13.

[21] Kobayashi Junko. 2008. “Shutoken no Ainu minzoku ni yoru shomei katsudo-Nihon seifu ni ‘Senju minzoku’ to mitomesaseru tame ni.” Senju minzoku no 10-nen nyusu 144: 10.

[22] Ainu Utari Liaison Group (Ainu Utari Renrakukai) is composed of four main organizations: Rera no Kai, Tokyo Ainu Kyokai, Kanto Utari Kai, and Pewre Utari Kai, all located in the greater metropolitan area. (Ainu Utari Renrakukai blog)

[23] Specifically, the UNHCR Working group issued the following comments, “Review, inter alia, the land rights and other rights of the Ainu population and harmonize them with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (Algeria); Urge Japan to seek ways to initiating a dialogue with its Indigenous peoples so that it can implement the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (Guatemala)” (Online, Accessed August 22, 2008).

[24] Imazu Hiroshi cited in Ito, “Ainu press case for official recognition,” Japan Times, 23 May 2008.

[25] See for example article on the Kunashiri Project and article on Suzuki-backed aid to Kunashiri, also see the high court’s February 2008 ruling on Suzuki’s case.

[26] On July 2, 2001, Suzuki stated, “I think it’s reasonable to say [that Japan is] a ‘one nation, one language, one race/ethnicity nation-state.’ In Hokkaido, there are these people known as the Ainu, and I’m sure there are those who will object to this comment, but they [the Ainu] are completely assimilated now” (Hokkaido Shimbun. July 3, 2001). At the time Suzuki was an upper house legislator representing the Liberal Democratic Party.

[27] For discussion of Suzuki’s influence on Tahara’s candidacy, see Japan Times article.

[28] In fairness, I should note that Suzuki reportedly negotiated with top representatives of the Ainu Association in a closed-door meeting in October 2001, and then held a press conference where Association officials agreed that they issue had been resolved (lewallen field notes, Sapporo, May 2007).

[29] The Governor of Sakhalin stated in 1994 that he recognized Ainu as indigenous peoples, as well as their former inhabitation of the so-called Northern Territories, i.e. Etorof, Kunashiri, Shikotan, and Habomai (Hokkaido Ainu Association. 2001. Kokusai Kaigi Shiryoshu, 1987-2000 [Records from international meetings] Sapporo: Hokkaido Ainu Association.).

[30] Note these comments from an endorsement speech for Upper House Candidate Tahara Kaori in May 2007: “If we succeed in establishing Ainu rights, Japan will for the first time be in a position to share international standards and international values [with the rest of the world]. Through that, we can find a solution for Japan’s weak point, the energy question, and improve relations with Russia…Northern Territories’ residents recognize Ainu to be an indigenous people; the Russian government also recognizes Ainu indigeneity. By properly calling for [recognition of] Ainu indigeneity, I believe we can launch a new approach to the movement to return the Northern Territories, and [work toward] a solution” (Speech: Suzuki Muneo. May 2007, translation by author.)

[31] Legislators in both houses were reportedly in attendance for the yes vote; although one legislator later claimed he “did not understand the implication of the Resolution” after voting in favor of it (Interview: Sato Y., 16 September 2008.)

[32] The ruling Liberal Democratic Party cited this text as “too emotional”: “We must acknowledge the historical fact that, in the course of Japan’s modernization, because Ainu people were constrained as forced labor and exploited, destruction of Ainu culture and society was accelerated, and in addition, as a result of the so-called assimilation policy, their traditional lifestyles were restricted and eventually prohibited, and due to the damage resulting from these policies, great numbers of Ainu persons were subjected to discrimination and forced to live in poverty even though they are Japanese citizens and equal under the law (Original Paragraph 2 of the “Resolution calling for the Recognition of the Ainu People as an indigenous people of Japan”).

[33] Online, Accessed 16 September 2008.

[34] Suzuki, Muneo “June 24 Shitsumon Shuisho” cited in Kobayashi, Junko. 2008. “Ainu Mosir 2008 ‘Natsu’.” Senju minzoku no 10-nen nyusu 147: 2-4.

[35] Interview: Abe K., September 7, 2008.

[36] According to the Ainu Utari Renrakukai’s survey of Diet legislators conducted in February 2008, while a handful of legislators had an extraordinarily high level of awareness and concern about Ainu issues, the majority were poorly informed (Kobayashi, Junko 2008. “2008-nen harukara natsu he, Ainu minzoku no doko – Senju minzoku no kenri kakuritsu wo motomete.” Senju minzoku 10-nen news 143: 14-15). While the survey had a 10% response rate, it should be noted that respondents were likely self-selected with a prior interest in Ainu issues which compelled them to respond.

[37] The full text of both appeals is available in English and Japanese Online.

[38] Kano Oki’s website

[40] Ainu Rebels website

[41] This third objective aiming to link indigenous relationships with the natural environment to ecological practice served as a central symbolic metaphor for marketing the IP Summit to indigenous guests, supporters, and funding agencies.

[42] By that extension, all settler nations, including Canada, the US, Australia, and New Zealand, for example, may also be considered as erstwhile and ongoing colonizers with varying degrees of recognition among the general population and not always satisfactory government policy advocated by different administrations. Indigenous-identified persons from these settler nations often correct discussion of “post-colonialism” by emphasizing that their own experience of colonialism is ongoing or “advanced colonialism.”

[43] The principal Okinawan group now sending advocates to the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues is the Association of Indigenous Peoples in the Ryuukyuus (AIPR). They have worked closely with the Shimin Gaikou Center, a Tokyo-based NGO which has also supported Ainu representatives’ attendance at the UNPFII in New York and the Working Group on Indigenous Populations in Geneva. Okinawans seeking recognition as indigenous peoples represent a tiny fraction of the larger Okinawan population, even among those Okinawans who seek independence. See Hook, Glenn and R. Siddle. 2003 Japan and Okinawa: Structure and Subjectivity. Routledge: New York for more discussion of the Okinawan indigenous advocacy movement.

[44] I do not intend to claim that the Ainu movement will necessarily follow a similar trajectory of empowerment and political mobilization as evident in other indigenous communities. Canadian First Nations, New Zealand Maori, Australian Aboriginals and Sami, for example, each have separate histories of colonial invasion and treaty-building with their respective nation-states, and their paths to rights recovery each involve separate trajectories. In particular, because Ainu lack any sort of treaty with the Japanese government they face a formidable challenge in future legal action. But it is worth noting that many Ainu activists perceive indigenous peoples overseas as comrades in work toward political rights recovery work.

[45] Kayano, Shiro. “Reflections on the Indigenous Peoples Summit in Ainu Mosir 2008.” August 2008.

[46] Personal Communication: IPS delegate, August 2008.

[47] Kayano, Shiro. “Reflections on the Indigenous Peoples Summit in Ainu Mosir 2008.” August 2008.

[48] IPS Caravan Tour Blog.

[49] Indigenous peoples have witnessed an increase in droughts, desertification, coastal and riverbank erosion, erratic weather patterns (stronger hurricanes, typhoons, flooding, extreme cold/heat), an increase in tropical diseases and disease-resistant insects, loss of biodiversity, changes in flora and faunal habitats and related food insecurity due to speciation change, and loss of agricultural land to the above factors.

[50] Tauli-Corpuz, Victoria and Tamang, Parshuram. “Trouble Trees.” Cultural Survival Quarterly 32:2. (Online).

[51] Tauli-Corpuz, Victoria and Lynge, Aqqaluk. “Impacts of Climate Change Mitigation Measures on Indigenous Peoples and on their Territories and Lands.” United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (7th session). April 2008: 4-5.

[52] For a more detailed review of the Nibutani Dam issue, see Stevens, Georgina. Forthcoming. “The Ainu, Law, and Legal Mobilization: From 1984 to 2007”. In Re-visioning Ainu Studies: A Critical Introduction, ed. Hudson, Mark, ann-elise lewallen, and Mark Watson, eds. Honolulu: Hawai’i University Press; and Levin 2001 Online.

[53] Tauli-Corpuz and Lynge 2008: 4.

[54] Cherrington, Mark. “Indigenous Peoples and Climate Change.” Cultural Survival Quarterly 32:2. (Online, Access date: 27 August 2008).

[55] Tauli-Corpuz and Lynge 2008: 4

[56] The Global Summit will be sponsored by the Inuit Circumpolar Council (Online, Access date: 30 August 2008).

[57] By “strategic essentialism,” I refer to symbolic and other strategies employed by indigenous peoples such as emphasizing shared values and similar histories to accentuate essential characteristics to achieve political objectives.

[58] Lopez, Kevin Lee. Returning to fields. Cultural Survival Quarterly. Winter 1994: 29.

[59] In some cases Ainu chose to be assimilated to have better access to education and livelihood, especially under Ainu Association campaigns in the 20th century. But in the early colonial period most Ainu resisted assimilation, although the lines where assimilation policies started and Ainu autonomy ended were often blurred.