Compulsory Mass Suicide, the Battle of Okinawa, and Japan’s Textbook Controversy

Aniya Masaaki, The Okinawa Times, and Asahi Shinbun

Japanese originals are available through links provided at the beginning of each of the articles that are included here.

For more than three decades, historical memory controversies have been fought over Japanese school textbook content in both the domestic and international arenas. In these controversies, Japanese textbook contents, which are subject to Ministry of Education examination and revision of content and language prior to approval for use in the public schools, repeatedly sparked denunciations by Chinese and Korean authorities and citizens with respect to such issues as the Nanjing Massacre, the comfort women, and coerced labor. In 2007, the most intense controversy has pitted the Ministry of Education against the residents and government of the Japanese prefecture of Okinawa. The issue exploded in March 2007 with the announcement that all references to military coercion in the compulsory mass suicides (shudan jiketsu) of Okinawan residents during the Battle of Okinawa were to be eliminated. The announcement triggered a wave of anger across Okinawan society leading to the mass demonstration in Ginowan City of 110,000 Okinawans addressed by the top leadership of the Prefecture. It was the largest demonstration since the 1972 reversion of Okinawa, exceeding even the response to the 1995 rape of a twelve-year old Okinawan girl by three US GIs.

We present three articles that illuminate the controversy and the tragic events of the Battle of Okinawa, including both the Japanese originals and English translations. Aniya Masaaki, an Okinawan historian and emeritus professor of International University examines the issues of the Battle and the textbook controversy, showing how the Ministry of Education rejected the testimony of Okinawan witnesses in favor of two soldiers who filed a defamation suit against novelist Oe Kenzaburo for his work on the military-enforced mass suicides. An Okinawan Times editorial that follows provides a detailed examination of the hair-splitting language politics that lie behind the Ministry of Education’s rejection of the reference to military force in the compulsory group suicide that was imposed on Okinawan citizens, and its partial retreat in the face of citizen anger. Finally, the Asahi Shinbun’s editorial offers a judicious examination of the politics of attempt to censor the issue from the nation’s textbooks. Together, these articles cast a brilliant light on the fraught political manipulation of the textbooks examination system. MS

Okinawan sculptor Kinjo Minoru’s relief depicting the horror of the Battle of Okinawa, during which many Okinawans were killed or forced to commit

suicide after seeking refuge in the island’s caves.

I. Compulsory Mass Suicide and the Battle of Okinawa

Aniya Masaaki

Translation by Kyoko Selden

Click here for the Japanese original

Textbook Inspection Which Denies Historical Truth

The Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (Monbukagaskusho, hereafter Ministry of Education) on March 30, 2007 announced the selection of high school textbooks for use beginning in 2008. With respect to the question of compulsory mass suicide (shudan jiketsu) during the Battle of Okinawa, they demanded revision of statements saying that there was a suicide order (jiketsu meirei) or coercion (kyoyo) by the Japanese military. This refers to statements in seven textbooks published by five companies.

The gist of the Ministry of Education’s comments is this: “The order to commit suicide (jiketsu meirei) by the Japanese military cannot be verified. The suggestion that people were cornered into compulsory suicide by the Japanese military leads to a false understanding of the Battle of Okinawa. Okinawan prefectural citizens protested saying, “this distorts the truth of the Battle of Okinawa.” The Okinawan Prefectural Assembly and all the municipal assemblies protested the ruling by the textbook examiners concerning military involvement in compulsory suicide, unanimously passing a resolution demanding retraction of the order to revise the texts.

However, the Ministry of Education rejected the claim of Okinawan citizens, merely reiterating that “The textbook inspection counsel decided this”, and ignoring the unanimous view of Okinawan citizens.

Concerning the disaster experienced in the Battle of Okinawa, there have been various attempts to warp understanding and lead historical awareness astray.

One such move concerns the Tokashiki, Zamami, and Kerama islands of the Kerama Island group. The Japanese military on the Kerama Islands had 300 suicide attack boats and approximately 300 men in the marine advance corps, along with 600 affiliated members of a special water-surface work corps comprised of Koreans. There was also a locally-drafted defense corps and volunteer corps that were incorporated into the defense corps of the island.

The marine advance corps on Kerama Islands was the army’s suicide attack corps meant to destroy enemy ships with one-man suicide boats carrying 120 kilogram torpedoes. The actual situation of this corps has been the subject of exaggerated reports, but I understand that local people had discomforts and doubts about “the army’s marine suicide corps.”

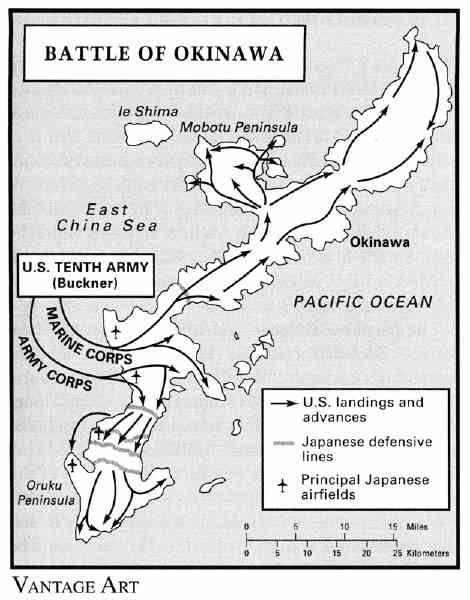

On March 26, 1945, the American military, with the support of artillery launched from both sea and sky began landing on Kerama Islands, and by the 29th had seized nearly the entire area. The fact is that the army’s attack boats did not attack even a single enemy boat.

During these battles, horrendous “mass suicide” (shudan jiketsu) of citizens occurred on Keruma, Zamami and Tokashiki Islands. This means that the inhabitants were forced to commit suicide by the coercion (kyosei) and inducement (yudo) of the Japanese military. But, the military leaders of the island now claim that “there was no military order.”

The family of Akamatsu Yoshitsugu, the former colonel who headed the military on Tokashiki, and Umezawa Yutaka, the former major who headed the military on Zamami, brought suit in the Osaka court against Oe Kenzaburo and his publisher Iwanami for his book Okinawa Notes, on grounds of “disparaging their reputations” and demanded compensation for damages. Calling this trial a lawsuit on false charges concerning Okinawan mass suicides “Okinawa shudan jiketsu enzai sosho”, they criticize Oe and Iwanami.

The plaintiffs claim that “Shudan jiketsu of inhabitants on Tokashiki and Zamani Islands were not by military order. They chose death with lofty self-sacrifice spirit.”

This is not merely an issue of reputation damage, but a revisionist scheme to justify aggressive war and acquit the imperial army of responsibility for its atrocious deeds. Statements by former military officers in Okinawa, who welcome field surveys by groups like the Liberal View of History Group and government officials, are distorting understanding of the battle of Okinawa. The textbook review this time concerning shudan jiketsu, adopted without verification the claims by unit leaders who say there was no military order. The testimonies by the people of the islands who were forced to kill close relatives were probably ignored as not credible. They are looking at .things from the perspective that testimonies by the commanders alone have credibility. It is out of the question to use the one-sided claims by Akamatsu and Umezawa, who are involved in the lawsuit, as the foundation for textbook approval.

The Battle of Okinawa on Which the Maintenance of the National Polity (Kokutai) Rests

The Battle of Okinawa, fought with the understanding that Japan’s defeat was inevitable, was the last ground combat between Japan and the US in the Pacific War. For the Japanese imperial government, the maintenance of the national polity was the first principle, and gaining time to prepare for the decisive battle on the mainland and negotiations for the conclusion of the war were crucial.

Former prime minister Konoe Fumimaro, on January 14, 1945, right before the Battle of Okinawa, memorialized to the emperor that the war situation had reached a grave situation.

Regrettably, defeat in the war has already become inevitable . . . . Defeat in the war will constitute a great flaw for our national polity (kokutai), but the consensus of England and the US has not yet gone so far as reforming (henkaku) the national polity . . .Therefore, if it is just defeat in the war, I do not think that we need worry so much in terms of national polity . . . What we have most to fear from the viewpoint of the maintenance of the national polity, is communist revolution which could occur following defeat in the war.

Therefore, from the perspective of preserving the national polity, I am convinced that we should think about the way to conclude the war as soon as possible, by even a single day . . . . (Hosokawa Morisada, Hosokawa Nikki (Hosokawa Diary))

The report by former Prime Minister Konoe is remarkable for openly explaining to the emperor the need to conclude the war as a member of the Japanese leadership. But the main point is that although defeat in the war was inevitable, rather than defeat itself, he was most concerned about the disintegration of the ruling structure by the imperial system (tennosei shihai kiko) by a communist revolution. To Konoe’s advice the emperor responded “I think it is quite difficult unless we achieve a military result just once more.” This indicates that the Showa emperor, even at this late point, had passion for leading the war effort.

The battle of Okinawa was “a battle on which the national polity hung,” yet one which presupposed Japan’s defeat. It is said that Okinawa served as “a stone to discard for the sake of the defense of the mainland,” but in fact it was “a battle to postpone the decisive battle on the mainland” and to gain some time for the preparation of that battle on the mainland and to negotiate the end of the war, and was not a battle to protect the people (kokumin) of the mainland. It was a preliminary battle before eventually taking the entire nation (kokumin subete) to death along with the Emperor.

The Japanese imperial government, in preparation for the final battle on the mainland, reinforced its total war system intended to mobilize the entire nation.

On May 22, 1945, the wartime education law (senji-kyoiku rei) was made public and even elementary schools and schools for the blind, deaf and dumb were ordered to organize student military units. On June 23, when the Okinawa defending force (32nd Battalion) was defeated and systematic fighting ended, a volunteer soldiers law was promulgated and women, too, were ordered to serve in national volunteer combat units.

On July 8, 1945 in Tokyo, military units of the Okinawan Normal School and the Okinawan Prefectural First Middle School were honored in a ceremony without the presence of the awardees. Minister of Education Ota Kozo told students throughout the country to follow the student military units of Okinawa and dedicate their lives in order to defend the national polity. (Asahi Shinbun July 9, 1945).

When the Japanese imperial government accepted the Potsdam Declaration, maintenance of the national polity was the central issue.

On August 6 and 9, the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, destroying the cities. But the Japanese leadership was preoccupied with the threat of Soviet entry into the war, more than with the destructiveness of the atomic bomb.

On August 8, 1945, the Soviet Union renounced the Soviet Union-Japan neutrality treaty, declared war and attacked Manchuria, Sakhalin, and North Korea. Consequently, the Japanese leadership felt the crisis of the imperial system and decided to bring the war to conclusion.

In the middle of the night on August 9, an imperial conference was held. At 2:30 a.m. on the 10th they accepted the Potsdam Declaration on condition of the maintenance of the national polity (kokutai goji). This was called an imperial decision.

Anami Korechika, then Minister of the Army, writes in his diary:

With the understanding that the conditions stated in the three countries’ combined declaration dated from the 26th of last month do not include the demand to change the emperor’s prerogative to rule the state, the Japanese government accepts this.

A Japanese politician has said that by dropping the atomic bombs “Japan’s defeat was made earlier, so it can’t be helped.” [The reference is to former Defense Min. Kyuma Fumio. Tr.] But this is a thoughtless statement by one who follows US policies while being ignorant of the affliction of citizens.

Why did the US drop the atomic bombs? Young people who have studied in Hiroshima and Nagasaki the reality of the bombing explain their findings clearly as follows.

- The US wanted to carry out attacks on the cities to display the bomb’s power. The ability to destroy with shock waves and ultra-high heat, the influence on human bodies and the environment by radioactivity. The atomic bomb is not a matter of a single moment à there is also secondary radiation and radiation in the womb. Hibakusha are not only Japanese à there were also Koreans and Chinese forced laborers (kyosei renko) as well as allied POWs.

Memorial for the Korean victims

of atomic bombing in Hiroshima

- They proudly flaunted the power of the atomic bomb to the Soviet leadership, a strategy that anticipated the US-Soviet postwar conflict.

- The B-29 which set out from Tinian in Micronesia at 2:49 a.m. on August 9 dropped the atomic bomb on Nagasaki at 11:02. That aircraft landed at Bolo Airport in Yomitan in the main Okinawan island at 1:09 on the 9th. After refueling it returned to Tinian at 22:55 on the 9th. At that time, US forces in Okinawa had set up an airport with a 2,000 meter runway that could accommodate B29s.

Compulsory Mass Suicide Forced by the Imperial Army

The Okinawa defense force issued a directive to Okinawan prefectural citizens calling for unification of the army, government and civilians living together and dying together (kyosei kyoshi), and stating that even a single tree or blade of grass should be a fighting power. They mobilized for battle all people, down to young and old, women and children.

The military and paramilitary locally recruited in Okinawa numbered more than 25,000 (soldiers on active duty, drafted soldiers, defense units, student units, volunteer units, etc.). We have to realize that one fourth of the Okinawa defense force were “Japanese soldiers” coming out of Okinawa prefecture. It is a mistake to think that Japanese forces in the battle of Okinawa were exclusively officers and men from the mainland (Yamato troops).

During the last stages of the battle of Okinawa (June-July) the American forces indiscriminately attacked Japanese forces and residents of the area within caves and called this “Jap hunting”.

The imperial army drove residents from shelters, took their food, prohibited them from surrendering, tortured and slaughtered them on grounds of suspected spying. They forced people into “mutual killing” among close relatives, and left the sick and handicapped on the battlefield.

The war dead among civilians in the battle of Okinawa is estimated at more than 150,000.

When we think about the damage to citizens in the battle of Okinawa, shudan jiketsu can be raised as the most peculiar case.

First of all we have to clarify the term shudan jiketsu.

When we say “jiketsu” (self-determination, suicide) the precondition is “spontaneity, voluntariness of those who choose death.” It is impossible for infants and toddlers to commit “jiketsu” and there is no one who spontaneously kills close relatives.

Mutual killing of close relatives, meaning that “parents kill young children, children kill parents, big brothers kill little brothers and sisters, and husbands kill their wives,” occurred on the battlefield where the imperial army and citizens mingled.

In Army Strategies in the Okinawa Area compiled by the War History Office of the Ministry of Defense, it is written: “They achieved shudan jiketsu and died for the imperial country with a sacrificial spirit in order to end the trouble brought on combatants.” But this claim goes against the facts. Citizens on the battlefield did not choose death voluntarily.

Although there are numerous interrelated factors, basically people were forced to kill close relatives by compulsion of the imperial army and local leaders who followed the imperial army. Enforcing the mutual killing of close relatives is of the same quality and the same root as the killing of citizens by the imperial army.

One cannot call the death of people who “were forced” or “cornered” shudan jiketsu [if the term indicates voluntary suicide]. It is improper to call this reality shudan jiketsu. Hindering properly conveying reality, it invites misunderstanding and confusing.

The term shudan jiketsu has been used since the 1950s and some say that “it walks on its own with an established meaning,” but if one uses the term shudan jiketsu without explaining the realities behind it, that invites misunderstanding and confusion. The reality of the term shudan jiketsu, I must reiterate, is “residents mass death by the imperial army’s coercion and inducement.”

Behind “residents mass death” in the Battle of Okinawa was imperial subject education (education to make everyone an imperial subject) which rendered dying for the emperor the supreme national morality (kokumin dotoku). In the Battle of Okinawa, “the unification of the military, government, and civilians living together and dying together” was emphasized, and “a sense of solidarity about death” was cultivated. At that moment, knowledgeable Okinawans played essential roles, including those in the Association of Reservists, the Support Group of Adult Men, and police and military affairs chiefs of local and municipal government.

When given hand grenades by the Japanese military, leaders of the islands accepted them, thinking it natural that “all residents die when the moment demands”. We cannot, however, think of this as “spontaneity and voluntariness” of “shudan jiketsu”. This was an era when it was impossible to decline “death” ordered by the imperial army.

The extreme fear of “brute Americans and British” [cultivated by the Japanese military] was a factor that made people choose death. Japanese military experiences of slaughter of Chinese people on the continent since the “Manchurian Incident” was widely discussed; and about the fate of residents at large at the time when the war turned out to be a “losing battle”, people despaired anticipating plunder, violence, slaughter by the American military. There were returned migrants who thought “the American military can no way be expected to kill residents”, but returnees were regarded as suspected spies and hence were unable to speak positively. To make such a statement was to court denunciation as a spy and slaughtered.

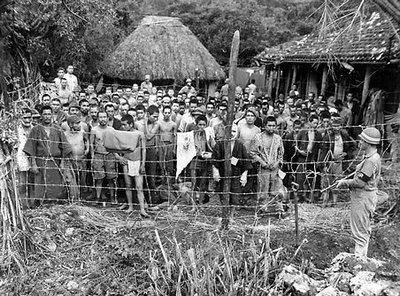

A Marine guards Japanese prisoners of war after the Battle of Okinawa.

More than 148,000 civilians died in the campaign.

There are people who were driven by the perverse idea that, rather than seeing female siblings and wives being killed cruelly and outraged by brute Americans and Brits, it was an act of love by close relatives to kill them with their own hands.

The fear of spy hunting by the imperial army accentuated the sense of despair among residents. The imperial army’s policy was never to hand over residents who knew military secrets. To accept the protection of the US military was regarded as spying. Residents positioned between the Japanese and American military were driven to “death”. Their hope to live was cut off by the shelling of the islands. Knowing that there was no escape route, they anticipated a cruel death. That too was one cause of their “hurrying to death”.

“Mass death of residents” took place when these elements joined together, causing panic that led to mutual killing of close relatives in local communities. Fear and madness overwhelmed village communities.

“Mass Death” in Encircled Areas

At the time of the Battle of Okinawa, had lost the control of the sea and sky of the entire area of the Southwest islands had passed to the US military. Communication and transportation with Kyushu and Taiwan were cut off and the islands were surrounded. The Okinawa defending force gave orders about matters involving the jurisdiction of the prefectural and local governments, unifying the military, government and civilians to live together and die together. All actions of prefectural citizens were controlled by commanders of stationed forces. Here there was no civil government. This kind of battlefield was designated “encirclement areas” in military terminology. These areas were designated by “martial law” as ones to be on the alert when surrounded or attacked by the enemy.

In such areas, commanders of stationed forces wielded full power. This overrode the constitution, and all legislation, administration and jurisprudence were under military control. During the Battle of Okinawa, martial law was not proclaimed, but the entire Southwest islands were virtual encirclement areas. It was for this circumstance that the administrative authority of the prefectural governor and mayors of villages was ignored and the stationed forces handled everything as they pleased. Directives and orders to local residents were received as “military orders” even if conveyed by town and village governments and local leaders.

On Tokashiki Island of the Keremas, Col. Akamatsu Yoshitsugu wielded total authority. On Zamami Island, Major Umezawa Yutaka held complete authority. The village administration was placed under the control of the military; there was no civil administration. Under military rule, those who played an important role in communicating military orders were military affairs directors of the village office.

These were local leaders who took charge of military affairs including coordination of the draft list, verification of the whereabouts of people of draft age, handling of such things as draft delay petitions, distribution of draft cards, and aid to bereft families of war dead and wounded soldiers.

The main duty of military affairs directors at the time of the Battle of Okinawa was to draft soldiers demanded by the stationed forces, to hand them over to the army and to communicate military orders (supply of labor power, evacuation, assembly and eviction) to the residents.

Toyama Majun, who was a chief of military affairs of the village of Tokashiki, testifies:

On March 28 at Fijiga (katakana) in the upper reaches of the On’na river, the collective death (shudanshi) incident of residents occurred. At that time, defense unit members brought hand grenades and urged residents to commit “suicide”.

This testimony by the military affairs director vividly conveys the reality of residents “shudanshi”. One can see that a military affairs director, who conveys the military order in an encirclement area, bore a crucial responsibility. Japanese citizens had been taught that a military order was “the emperor’s order”. There was also the aspect that people believed that “choosing death” rather than become POWs was “the way of imperial subjects”. They were, in accord with the instruction of local leaders and the imperial army, made to implement the field service code (senjinkun), which said “Do not live to receive the humiliation of becoming a prisoner”.

This article was published in Gunshuku mondai shiryo (Disarmament Review), December 2007. Aniya Masaaki is Professor emeritus of Modern Japanese History at Okinawa Kokusai Daigaku, (Okinawa International University).

II. A Political Decision that Obscures Historical Reality: “Involvement” approved, “Coercion” Kyousei) disapproved in Okinawa Mass Suicide Textbook Treatment.

Okinawa Times editorial

Translation by Kyoko Selden

Click here for the Japanese original.

Regarding the high school Japanese textbook examination issue, the Textbook Approval Council (Kyoukasho-you Tosho Kentei Chousa Shingikai, Investigation Council for Examining and Approving Publications for Textbook Use) reported to Tokai Kisaburou, the Minister of Education and Science, the results of the deliberations on wordings related to “mass suicide (compulsory mass death, shudan jiketsu)” during the Battle of Okinawa, concerning which six textbook publishers had petitioned for revision (teisei shinsei, a petition to revise an already approved textbook).

We would like to ask all high school students within Okinawa prefecture:

Of the following three sentences, (1) was the original draft [in one of textbooks in question]. Later, at the direction of the Ministry of Education and Science and of the Textbook Approval Council at work, it was rewritten to (2) [this version was approved in March 2007]. In response to the strong protest from many Okinawan citizens, the textbook publisher petitioned to revise the expression. As a result, the wording changed to (3) [this has met approval]. Now, concerning these three sentences, what changed and how? Why did these changes have to be made? What was the aim?

(1) “There were residents, who, by the Japanese military, were driven out of shelters or driven into mass suicide.” (Nihon-gun ni yotte goh wo oidasare, aruiwa shuudan jiketsu ni oikomareta juumin mo atta,)

(2) “There were residents, who, by the Japanese military, were driven out of shelters, or committed suicide.” (Nihon-gun ni goh kara oidasaretari, jiketsu shita juumin mo ita.)

(3) “There were residents who, by the Japanese military, were driven out of shelters, or were driven into mass suicide.” (Nihon-gun ni yotte goh wo oidasaretari, aruiwa shuudan jiketsu ni oikomareta juumin mo atta.)

How do these sound?

Because the changes are such that they are hardly discernible without careful comparisons, we would like you to read them slowly twice, and thrice over.

In version 1, the relationship is clear between the subject, “the Japanese military,” and the predicate, “were driven to mass suicide.” In version 2, however, the subject and the predicate are disconnected, leaving the relationship between the two ambiguous. Version 3 is like one of the two peas in a pod together with the original. One can say that it nearly restores the original, yet it gives the impression that the connection between the subject and the predicate is somewhat weaker.

What comes in and out of sight through this series of editing stages is the intention behind: “if possible we want to erase the subject, the Japanese military,” “we want to make the relation between the Japanese military and the mass suicide ambiguous.”

The conclusion of the Textbook Approval Council can be summarized into the following three points.

First, the Council has not withdrawn its Approval Statement (kentei ikensho, a written opinion or a statement of one’s views). Second, it does not adopt an expression like “were coerced by the Japanese military,” which specifies military enforcement. Third, wordings like “were driven” by the Japanese military, which indicate military involvement, were approved.

This means that they tried to settle this issue by restoring “coercion,” which had disappeared in the approval examination process, in the form of “involvement.”

What Characterizes the Battle of Okinawa

The resolution adopted by the Okinawan protest rally of September 29 had two points, “withdrawal of the Approval Statement” and “restoration of the wording.”

Thousands of protesters in Ginowan, Okinawa, demanded that

Japanese government drop plans to remove references

in textbooks to the coerced mass suicides on their island in 1945.

Certainly, the Okinawans’ consensus moved the Textbook Approval Council, resulting in a degree of restoration of the wording. It is not at all the case that Okinawan efforts were for nought.

However, despite the fact that textbook publishers petitioned for approval of revision while carefully working out the wording with the aim of restoring “coercion,” the Council judged that “the revision cannot be approved with the wording as it is,” demanding another round of rewriting.

Why they shun the use of the term “coercion” to this extent is simply incomprehensible.

In deliberating on the petitions for revision, the Approval Council listened to the opinions of eight specialists from inside and outside the prefecture. One specialist commented that residents being driven into a corner by the Japanese military was the very characteristic of the Battle of Okinawa, and that the presence of the Japanese military played a decisive role.

Another specialist pointed out that the policy that says, “those without combat ability should commit suicide (jiketsu, gyokusai) before becoming prisoners of war,” was based on a strategic principle across the entire military. It was not an issue at the level of whether or not a specific commanding officer ordered it at a specific point in time.” We agree.

We must not confuse the issue of the existence of a commander’s order with that of coercion by the Japanese military.

Reforms Are Necessary for the Textbook Approval System

In response to the objection from Okinawa, some said, “There should be no political interference.” But, if that is the case, I would like them to answer the following question as well.

Until 2005, reference to military coercion had been approved. Why, despite the fact that there has been no great change in academic understanding, did the issue this time receive an examination comment? Why is it that the Council made the claim of one party in a trial in progress the foundation of its examination comment?

What has been exposed this time is the locked room nature of the examination system. The contents of the deliberations of the Textbook Approval Council are private, and the proceedings have not been made public. Details of examination comments, as I understand, are not put into writing. The majority opinion is merely stated orally.

The Council passed the textbook investigation officials’ draft statement with no in depth discussion. In what relation the investigation officials stand to the Council too remains veiled. [A textbook draft first goes to Kentei chousakan (examination and approval investigation officials), who, or one of whom, drafts an examination and approval (Kentei) statement. If necessary the textbook goes also to a specialist committee member (sen’mon iin) or members. Then the texbook goes to the Textbook Approval Council.]

This editorial appeared in the Okinawa Times, December 27, 2007

Textbook Review Council Report, part one of two.

III. Mass Suicides in Okinawa

Asahi Shinbun editorial

Click here for the Japanese original.

Education minister Kisaburo Tokai announced Wednesday reinstatement of history textbook references about the Imperial Japanese Army driving civilians into committing mass suicide in Okinawa in the closing days of World War II. The Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology approved revisions submitted by six publishers on passages concerning the 1945 Battle of Okinawa for senior high school textbooks to be used from the 2008 academic year starting in April.

As a result of the revisions, these textbooks will contain passages with the following content:

Many local residents were driven to commit mass suicides because of the Japanese military’s involvement.

Due to coercive circumstances over the military’s prohibition on civilians becoming prisoners of war, many local residents felt they were driven into mass suicides and mutual killings.

In textbook screening conducted in spring this year, the education ministry ordered publishers to remove all references to the military’s involvement in the mass suicides as well as statements that people were forced into the gruesome acts by Japanese soldiers.

The ministry says the changes are based solely on applications from the textbook publishers and don’t represent a retraction of its original decision. Probably, it would be closer to the fact to say that the ministry was forced into a virtual retraction of the decision in the face of strong public criticism about it, mainly from people in Okinawa.

The blame for this fiasco clearly rests with the extraordinary instructions the ministry issued to the publishers. The ministry had all references to the military involvement in mass suicides removed. It argued these passages could generate the misunderstanding that all these actions were carried out under orders from the military.

After the publishers submitted revisions early last month, the education ministry asked the Textbook Authorization and Research Council, a ministry-appointed panel to check the proposed changes. The council heard from experts, including academic researchers on the Battle of Okinawa, and then developed its own opinions as the basis for debate on the revisions.

While insisting there is no solid evidence to confirm direct orders from the military, the council admitted that education and training by the wartime government were behind the mass suicides. The panel also pointed out that the distribution of grenades among local residents by the army was a key factor that created the situation responsible for the mass suicides.

The council’s argument must be convincing for many people. In essence, it said people in Okinawa were driven to mass suicides under extreme pressure from militarism, which fanned fear about the invading U.S. soldiers among local residents and prohibited them from becoming POWs.

In its discussions on the proposed revisions, however, the council stuck to its insistence that straightforward expressions like “the military forced” civilians into mass suicide should not be used. This stance should be questioned.

It is hard not to wonder why the panel didn’t come up with such common sense opinions for the textbook screening this past spring. If it had done so, the panel would not have endorsed the reviews by the education ministry’s textbook inspectors. One of the panel members has conceded that they should have discussed the issue more carefully.

At that time, the government was led by former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, whose motto was to “break away from the postwar regime.” Was the expert panel in some way influenced by the Abe administration’s political posture? Ironically, this outrageous move by the education ministry caused the grueling wartime episode to attract unprecedented public attention.

Previously, most school history textbooks contained only brief descriptions about the mass suicides in Okinawa. The revisions submitted by the publishers also included descriptions about the social background for the tragedies. As a result, the textbooks offer much more information about the bloody battle fought in Okinawa in 1945.

The public controversy over the textbook references raged for nine months. A huge protest rally was held in Okinawa during that period, which gave many people the opportunity to learn not only about the bloodshed in Okinawa but also about the serious flaws in the ministry’s textbook screening system.

The bitter lessons from the experience should be used for the good of the nation.

This editorial appeared in The Asahi Shinbun, Dec. 27 and the International Herald Tribune/Asahi on December 28, 2007.

Kyoko Selden is a senior lecturer in Asian Studies, Cornell University and a Japan Focus associate. The first two volumes of her Annotated Japanese Literary Gems have just been published, featuring stories by Tawada Yoko, Hayashi Kyoko, Nakagami Kenji, Natsume Soseki, Tomioka Taeko and Inoue Yashushi.

Posted on Japan Focus on January 6, 2008.