By Aaron Gerow

History, like the cinema, can often be a matter of perspective. That’s why Clint Eastwood’s decision to narrate the Battle of Iwo Jima from both the American and the Japanese point of view is not really new; it had been done before in Tora Tora Tora (1970), for instance. But by dividing these perspectives in different films directed at Japanese and international audiences, Eastwood makes history not merely an issue of which side you are on, but of how to look at history itself.

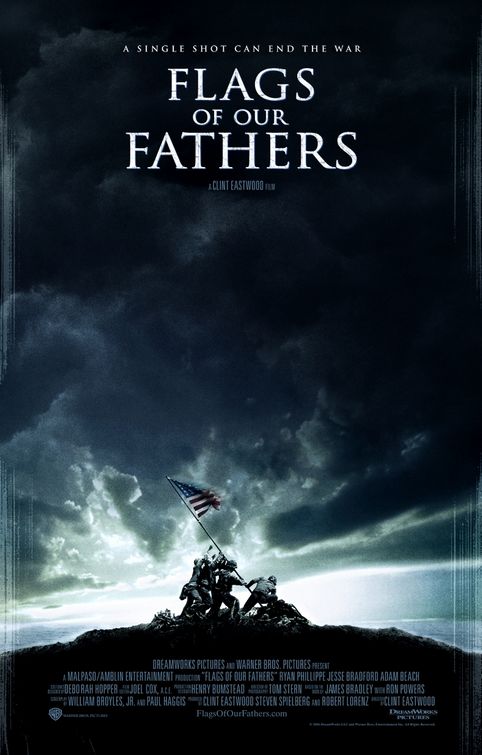

Flags of Our Fathers, the American version, is less about the battle than the memory of war, focusing in particular on how nations compulsively create heroes when they need them (like with the soldiers who raised the flag on Iwo Jima) and forget them later when they don’t. Instead of giving the national narrative of bravery in capturing Iwo Jima, the film shows how such stories are manufactured by media and governments to further the aims of the country, whatever may be the truth or the feelings of the individual soldiers. Against the constructed nature of public heroism, Eastwood poses the private real bonds between men; against public memory he focuses on personal trauma.

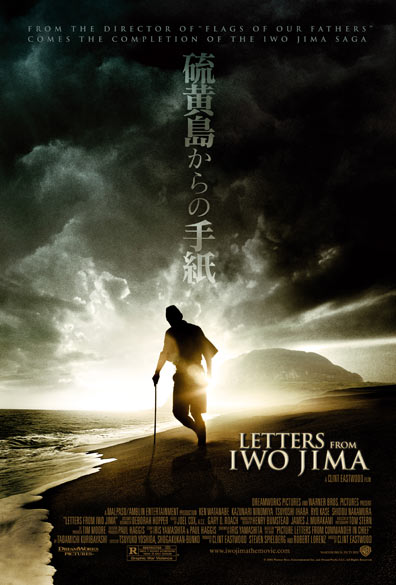

The Japanese edition, Letters from Iwo Jima, could—and perhaps should—have been about similar issues, but Eastwood changes his approach to history itself with this film. It, like Flags, begins decades after the war is over, but tells its story not through the traumatic flashbacks of the survivors, but effectively through the letters of soldiers unearthed from an island cave. Flags is about how to remember the war, giving a new view on an incident everyone knows; Letters is about listening to those who fought it, trying to create a memory tableau of something most people, including Japanese, know little about.

Mostly relating the battle as if it is the present, Letters is a more conventional war film. If Flags is an ambitious attempt to deconstruct the Hollywood war movie and similar media that work to create fictions of heroism, Letters, initially inspired by Eastwood’s encounter with the letters of General Kuribayashi Tadamichi, the Japanese commander on Iwo Jima, appears more simply as an American effort to understand the complex human beings on the other side, to tell the world that they were brave too.

And some of the figures are fascinating. Kuribayashi (Watanabe Ken) had studied in the United States, wrote loving letters to his son with comic illustrations, and protected his men against abusive officers; his close associate, Baron Nishi (Ihara Tsuyoshi), was a gold medalist at the Los Angeles Olympics and a friend of Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks. These two are in conflict with more traditional officers like Ito (Nakamura Shido), who seem more concerned with achieving a glorious suicidal death than defending the island and thus delaying the Allied forces’ march on Tokyo. Under Kuribayashi’s unconventional command, a garrison that was supposed to fall in 5 days lasted for 36. (The result was that just 1,083 of Japan’s 22,000 troops from army and navy units survived. The United States suffered the highest casualties of the Pacific War to that time. The 70,000 Marines thrown into the battle suffered 26,000 casualties including 6,821 deaths.)

The fear when one country’s artist dabbles in another nation’s history, is that unwitting mistakes of fact and interpretation will be made. Usually the problem is inaccuracy or distortion, but that does not figure much here: the drama is convincing, the characters well developed, and the acting superior. The question is whether this film, like The Last Samurai, might unwittingly feed into and actually bolster the contemporary rise in chauvinist nationalism in Japan. Some of the Japanese ads for Letters from Iwo Jima in fact seem to promote the movie along those lines.

Eastwood does much to undermine the military glory. Despite ads touting the vigorous defense, very little of that is shown as the film quickly turns to the soldiers’ choice between suicide and surrender. Suicide itself is shown as a grisly—and in contrast to old Japanese war films—distinctly unaesthetic experience. Watanabe’s superbly acted Kuribayashi may show shades of Katsumoto (his character in The Last Samurai) in ordering a last charge. But there is none of Samurai’s overblown celebration of martial valor, since it is shot at night as a chaotic melee. The soul of Eastwood’s film is the baker-turned-soldier Saigo (Ninomiya Kazunari, in a strong performance), who has promised his wife to return alive and never fires a shot.

Yet one can sense Eastwood treading carefully, trying not to offend his audiences. The fact that Kuribayashi and Nishi emerge as basically liberal humanists friendly to America makes them more palatable to American viewers. Letters curiously also seems to parallel some of Japan’s recent war films like Aegis and Lorelei, which, by preaching life not glorious death, attempt to offer a kinder, gentler nationalism for contemporary Japanese (see my article in Japan Focus).

Yet just as Japanese atrocities are mostly shown in Flags and American crimes in Letters, so Eastwood completely avoids the controversial issue of how Japanese should remember the war—even though he allows some of his characters, one in fact ironically, to survive. The critique of national history through personal trauma that centers Flags is barely raised in Letters.

One thus wonders whether Eastwood, in honoring these other soldiers in Letters from Iwo Jima, may be unwittingly engaging in the same process of creating “heroes” that Flags of Our Fathers criticized, albeit for another country. The primary hero here is Kuribayashi and he is someone whom the virtually pacifist Saigo eventually comes to revere and actually fight for (though with a shovel).

Eastwood, however, by walking the tightrope between mutual deference and mutual criticism, remains somewhat detached and never openly declares what kind of hero Kuribayashi is (or should be): a public hero like the beleaguered flag-raisers in Flags, or simply a private hero (like Mike, the skilled sergeant in Flags) for a life-loving baker. Both remain open as possibilities and it is left up to the audience—and possibly the media context they inhabit—to decide. The National Board of Review of Motion Pictures voted Letters From Iwo Jima the best film of 2006, proclaiming it Eastwood’s “masterpiece”.

Some may urge him to take a clearer position, but perhaps his detached but deferential stance also reminds us that cinema, like history, can often be a matter of perspective. It is up to us, not just the films, to determine the perspective, as well as our history and our heroes.

Title: Letters from Iwo Jima

Director: Clint Eastwood

Starring: Watanabe Ken, Ninomiya Kazunari, Tsuyoshi Ihara, Kase Ryo, Nakamura Shido

Title: Flags of Our Fathers

Director: Clint Eastwood

Starring: Ryan Phillippe, Jesse Bradford, Adam Beach, Barry Pepper, John Benjamin Hickey, John Slattery

Aaron Gerow is assistant professor in the Film Studies Program and in East Asian Languages and Literatures at Yale University. He has published widely in Japanese and English on Japanese cinema.

This is an extended version of a short review of Letters from Iwo Jima published in The Daily Yomiuri on 9 December 2006. It was published at Japan Focus on December 12, 2006.

For another review of Letters From Iwo Jima by a Canadian critic in Tokyo see.