The Re-emergence of Chinese in Jakarta

Andre Vltchek

Introduction by Geoffrey Gunn

As Andre Vltchek observed in the Indonesian capital, Jakarta, Chinese New Year offers a window on such questions as cultural identity, tolerance or lack of it on the part of the host community, and even the state of well-being, as measured by the passing of red envelopes stuffed with cash. Chinese in Indonesia have long been vulnerable, whether at the hands of the colonial Dutch administration or as scapegoats at the hands of the Suharto dictatorship, as suspected communists in 1965-66, or as too successful entrepreneurs, as in the May 1998 military-militia attacks upon the Jakarta Chinatown along with cukong-crony capitalist partners of Suharto himself. Vltchek describes a kind of “protective assimilation” response on the part of Indonesian Chinese. Actually historians have long distinguished laugeh (long time settlers from Hokkien, some of whom might also have embraced Islam) from singeh, or newer arrivals who, in turn, were also subject to assimilationist pressures. But few diasporic global Chinese communities have had to face the kind of repressive assimilation imposed by the Suharto dictatorship in Indonesia. In the late 1960s, tens of thousands of Chinese fled to China then in the throes of the Cultural Revolution only to be reviled as bourgeois opportunists, while most sought to melt into Javanese culture. Such appeared to be the final solution to the Chinese business community of Solo in central Java, when I visited in the 1980s. Not one Chinese character or feature (or face) remained on the main street in Solo, once a “typical” Chinese commercial street. But more than most “native” Indonesians would admit, Chinese cultural elements have also been assimilated into the Indonesian mainstream, from food (tofu products) to lion symbols, to Hokkien pronouns and expressions which enter Jakarta dialect. More than once in recent times I have observed big spending Indonesian Chinese tour groups visiting Hong Kong, speaking not Chinese but a standard form of Bahasa Indonesia among themselves. Matters are deceptive, as the same group may well reserve their native Hokkien for other destinations and private occasions. The assimilation question is a real-life problem as even newer waves of Chinese immigrants arrive in Pacific island countries from Tonga to East Timor. In 2009, for example, Papua New Guinea was the scene of week-long anti-Chinese riots, triggered by resentment that Chinese migrants displaced indigenous business. (Tonga had earlier experienced anti-Chinese riots in 2006). Typically, and Papua New Guinea was no exception, senior politicians and ministers were complicit in the illegal recruitment of mainland Chinese migrants.

On the eve of the Spring Festival several places all over Jakarta were decorated with red lanterns, dragons and lions. Temples and some houses even added fresh red paint to roofs and walls. Lions are dancing on improvised stages inside the malls.

|

Children admire a lion dragon |

The Year of the Tiger was being welcomed by lavish celebrations in several shopping centers, five star hotels and in some predominantly Chinese neighborhoods. Cultural events included traditional dances and music, as well as Chinese pop. At Taman Anggrek Mall this year’s theme was Boat of Fortune with a huge ‘junk regatta’.

One could easily point out that the capital city’s businesses are using Spring Festival to increase sales and that – as is so common in Indonesia – everything is about money and very little about culture or history. On the other hand, one could say that while not everything is going smoothly (there is heavy security at all Chinese events – proof that not everyone welcomes the return of some cultural pluralism in this archipelago where the majority and its dominant religion are accustomed to rule unopposed), at least it is going!

|

Commercializing the spring festival |

All this would have been unimaginable during the long decades when everything Chinese was banned in the wake of the massacres that ushered in the New Order of Suharto in 1966. Imlek as the Chinese New Year is called in Indonesia, was allowed to be celebrated publicly only since the Presidency of progressive Muslim cleric Abdurrahman Wahid. His successor Megawati Sukarnoputri proclaimed it a national holiday in 2003.

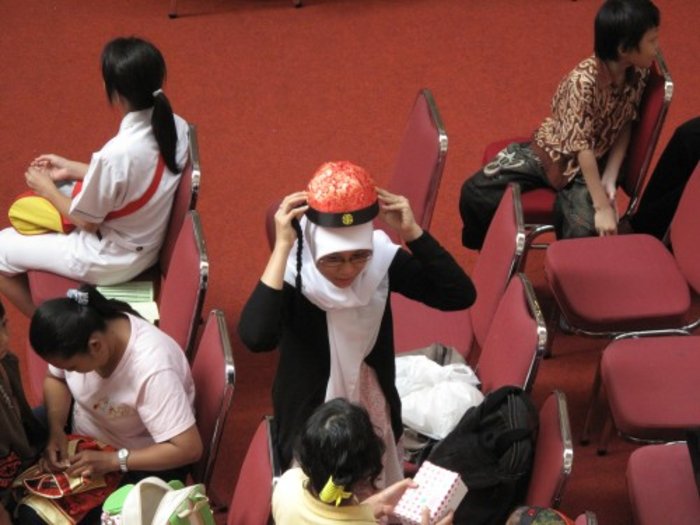

Suddenly it is becoming possible to see other ethnic groups mingling with their Chinese friends, admiring red shirts and jackets or tasting traditional dumplings and other delicacies. “I like red hats with long black tails”, smiles Yanti – a Muslim girl from Jakarta – as she tries one on at Puri Mall right over her headscarf.

Trying on a Chinese hat over a headscarf

“In my opinion, things are now much better than some years ago. There is not as much emphasis on race”, explained Johan Sharajan, a pianist of Chinese descent from the city of Bandung in West Java.

“As a minority, we have to thank Gus Dur (recently deceased former President Abdurrahman Wahid) for allowing this to happen. However, we are still celebrating Spring Festival in a very simple and subdued way so it will not be too conspicuous. We know our place – in Indonesia we are a minority. Actually, we would like to be able to celebrate like people in Hong Kong, Singapore or Kuala Lumpur, but I guess it is not yet possible.”

In the same city, howevere, his colleague and friend – a concert pianist and music teacher – complained that her student was insulted on the street as she was walking to her lesson, simply because she didn’t look “native” Indonesian.

While in theory things had improved (for instance, people can now choose to be Confucian – one “religion” that was recently added to the short list of faiths permitted by the state), racism in Indonesia is rampant. People who don’t appear like the majority – be they white, black, Chinese or Papuan – are commonly screamed at on the streets, even insulted, fingers pointing at them even as the nation proclaims its tolerance and cultural diversity (the official motto is: “unity in diversity”).

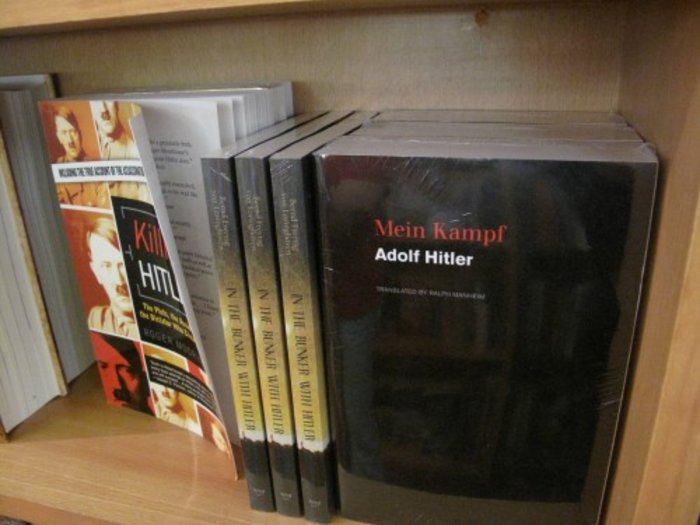

To illustrate the point: this author recently complained about Adolf Hitler’s (whose posters are on sale all over the country and who is admired by many Indonesians) Mein Kampf and other racist literature decorating several prominent shelves in the Japanese book chain Kinokuniya in Jakarta. When the staff showed indifference, even hostility to my protest, I began single-handedly destroying the book stock in front of the shocked public. Ushered to the back room, I had to face the local Indonesian-Chinese owner and his Javanese lieutenants.

|

Mein Kampf on sale at Kinokuniya Books in Jakarta |

After I explained what the book stands for, the owner made the swift decision to take all Hitler’s volumes off the shelves. He apologized and even asked me to give him a list of other racist books he should not allow in the store. But the local managers began protesting immediately making it obvious that the books were in the store at their initiative. In the end, the owner remained firm, perhaps especially in light of my argument that Mein Kampf promotes exactly what happened to the Chinese and other people after the 1965 slaughter in Indonesia. However, the zeal of the local staff for Hitler’s work and hostility toward patrons removing it from the shelves may be illustrative of the state of mind of the Indonesian public.

The Chinese minority in Indonesia has had a particularly tragic and painful past. Periodic pogroms throughout the long period of Dutch colonial rule were followed by others after independence, especially under the Suharto dictatorship. Even the anti-Suharto riots of May 1998 that led to the downfall of the dictator were marked by plundering of Chinese businesses and public gang-rape of Chinese women in Jakarta and elsewhere. Other anti-Chinese riots took place in Solo, Lombok and elsewhere.

Following the US-backed military coup of September-October 1965, General Suharto, his military clique and countless Muslim religious cadres killed an estimated 500,000 to 3 million people – Indonesian Communists, left-leaning intellectuals, union leaders, artists, teachers, but also members of the Chinese minority whom they accused of being connected to “Red China”. Consequently, everything Chinese was banned, from their language – both written and spoken – films, literature, even dragons and cakes.

Leading Indonesian historian, Asvi Warman Adam from LIPI (Indonesian Institute of Science) explained for this article: “Only the tiny group of ethnic Chinese in Indonesia had been privileged while the Chinese minority as such had been discriminated against since the colonial era and the events of 1965 just reinforced this discrimination. The regime portrayed the Chinese in a negative light so they could have a scapegoat – a target – whenever the masses got angry. Those Chinese tycoons who refused to applaud Suharto’s rule, such as the owner of the Astra Trading Company, were forced into bankruptcy. Those who accepted were rewarded – like Liem who got a clove and flour monopoly.”

One of the most critical Indonesian writers – Linda Christanty – argues: “Yes, Chinese people were allowed to celebrate Chinese New Year, but that does not obliterate the discrimination towards those who were political and suffered in the hands of Orde Baru (Suharto’s New Order). Before, everything Chinese was banned as it was identified with Communism. Schools using Mandarin language were closed. Chinese names had to be changed to Javanese as part of Soeharto’s Javanisation of the country. In my opinion, as long as the government does not rehabilitate those who were falsely accused of participating in the 1965 pro-communist rebellion (a rebellion that never really took place but served as justification for Suharto’s military crackdown), and as long as the communist stigma remains in our society, it would be ridiculous to even pretend that the Chinese people living in this country have real rights.”

|

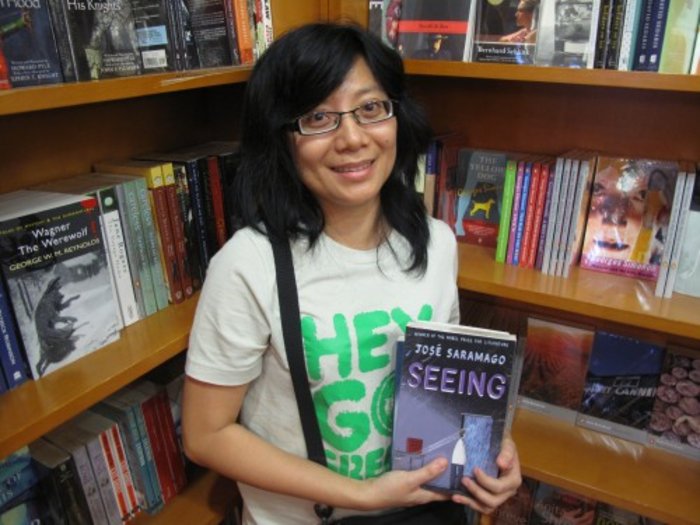

Linda Christanty |

Near Dharma Bhakti temple in Glodok (also known as Jakarta’s China Town, although almost all traditional Chinese houses were destroyed during Suharto’s reign), shopkeeper Julius (like many in Indonesia known by a single name) explains: “Here in Glodok, 90 percent of the inhabitants are of Chinese origin, but we don’t speak Chinese as for decades it was forbidden. Only some old people do. We also had to change our names to Indonesian ones after 1965. Now in theory we could apply to get back our original names, but the bureaucracy and expected bribes are such that I don’t know anyone who has succeeded so far. It is definitely not encouraged.”

As he speaks, the sound of prayers is coming from the temple. Dozens of beggars, many old and some small children but none apparently of Chinese descent, are lining up along the access road asking for money or food. Chinese men and women are taking boxes of food and donations from the temple, distributing gifts equally among the growing crowd dressed in rags.

|

Chinese feeding Indonesian beggars |

In the 1960’s and 70’s when Confucianism was banned, most Chinese Indonesians converted to Christianity. One of them was Hengky Senjaya, presently Indonesian head of Panasonic and a renowned art collector who commented, “We celebrate the Spring Festival in a very quiet way – we eat, women gossip, men play cards,” he laughs. “Now it is just a quiet tradition, nothing else.”

There is nothing quiet about Hotel Shangri-la’s plans for this year’s Spring Festival. 12 creatures of the Chinese zodiac decorate its lobby, restaurants prepare to offer lavish fare to a few fortunate Indonesians and to some foreigners welcoming any spark of diversity – bored in the cultural desert of this enormous metropolis dotted with chain services, eateries and shops but almost no cultural institutions.

In posh hotels and malls, red is the color again! But all these celebrations feel somehow forced and commercially driven. After all – how “Chinese” are the people who don’t even speak their own language, do not know their literature and films, and who can hardly cook even the most basic Chinese dishes? How Chinese are those who had to live through the mighty brainwashing of nationalist and religious propaganda, which intended and succeeded in making every city, town and village of Indonesia look almost identical – while producing a society in which almost all citizens think and feel the same? Even so, we wonder if repression has not strengthened various kinds of Chinese identity among significant numbers of Chinese. Of course, it is difficult for them to speak of this.

Criticism of the past and present by members of Chinese minority is very subdued – sadness and hopelessness has to be often guessed or read between the lines.

“Now things are much better and many Chinese traditions are promoted and are becoming visible in public”, says Rijanto Adjie – general manager of an industrial trading company whose origins are Chinese. “You can now see what we call barongsai – Lion and Dragon dances – performed by Chinese people but also increasingly by native Indonesians. I usually celebrate Spring Festival by visiting my parents and having a good dinner on the Chinese New Year’s Eve. The next day, younger members of the family are obliged to visit their uncles and aunts, with angpao (envelopes with money) distributed to the children. There is no special food here for the celebration. In Singapore, there is a special dish that we have to stir while saying wishes for the New Year. But you see, I don’t know the name of it, because I don’t speak Chinese…”

|

Barongsai at Mall Kelapa Gading |

The past has not yet been forgotten. The wounds have not healed. There is still discrimination, but once again red lampions are hanging from the ceilings of Indonesian malls, expensive cafes and even on some street corners in poorer neighborhoods. Dragons and lions have regained respect. Photos of landmarks of the PRC now decorate travel agencies and boutiques. Many Indonesians feel admiration for China while others feel envy, even fear. Indonesia produces little; its planes fall from the sky, ferries sink, and bridges collapse. This year China and Indonesia signed a free-trade agreement, yet even before it took effect, there have been calls for protectionism – indeed, there is no doubt that Indonesia, after almost half a century of market fundamentalism, can’t compete with China. The gap between the standard of living and development levels of the two countries is widening each year.

The Chinese minority in Indonesia is slowly regaining its voice – although it is not a voice that is distinctively Chinese. However, what is left of Chinese culture here (or what is imported from Singapore) is beginning to influence the Indonesian mainstream. The Spring Festival is now at least adding badly needed colors, vibrancy and optimism to otherwise bleak, polluted and desperate streets of Jakarta.

Andre Vltchek – novelist, journalist and filmmaker, wrote and photographed this article. An Asia-Pacific Journal associate, he is presently living and working in Asia and Africa and can be reached at [email protected]. He is co-editor with Tony Christini of Liberation Lit, a collection of art and criticism of social change, including contemporary liberatory fiction and criticism, poetry and visuals, and co-author with Rossie Indira of Exile: Conversations with Pramoedya Ananta Toer. His home page is here.

Geoffrey Gunn is author of Singapore and the Asian Revolutions, 2008 and an Asia-Pacific Journal coordinator.

Recommended citation: Andre Vltchek and Geoffrey Gunn, “The Re-emergence of Chinese in Jakarta,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 15-1-10, April 15, 2010.