Disarming Japan’s Cannons with Hollywood’s Cameras: Cinema in Korea Under U.S. Occupation, 1945-19481

Brian Yecies and Ae-Gyung Shim

Key words: Korean Cinema, Hollywood in South Korea, USAMGIK, Motion Picture Export Association, U.S. Occupation, film policy

Abstract

Reorienting the southern half of the Korean Peninsula away from the former Japanese colonial government’s anti-democratic, anti-American and militaristic ideology while establishing orderly government was among the goals of the U.S. Army Military Government in Korea (USAMGIK, 1945-1948). To help achieve this aim on a wide front and as quickly as possible, USAMGIK’s Motion Picture Section in the Department of Public Information arranged the exhibition of hundreds of Hollywood films to promote themes of democracy, capitalism, gender equality and popular American culture and values. While U.S. troops in the field enjoyed the increased availability and calibre of American feature films, the Korean government-in-waiting was affronted by their perceived immorality. Standard Korean film histories focus on the hardships endured by Korean filmmakers, and the conflicts among them, and on Hollywood’s monopoly of the screen in the era, a situation which USAMGIK film policy – strikingly similar to the ordinances previously set in place by the Japanese – assisted. This study demonstrates how many of these ‘spectacle’ films, which have hitherto largely gone unlisted, were designed to inculcate Western notions of liberty among Koreans, while distracting them from a tumultuous political scene. However, the films exhibited did not always live up to this lofty purpose. Along with positive portrayals of the ‘American way of life’, representations of violent, anti-social and misogynistic behavior were foreign to Korean cultural and aesthetic traditions, and often provoked negative responses from local audiences.•

In July 1950, within days of the start of the Korean War, hundreds of 16mm prints of Hollywood feature and short films and more than fifty film projectors were rushed from Japan to US Army and United Nations troops in the field. With many thousands of movies and over one thousand new projectors eventually sent from the United States, the Motion Picture Division of the Army’s General Headquarters, Far Eastern Command, went to great lengths to entertain the troops with some of the latest commercial releases – such as Sunset Boulevard (1950), The Next Voice You Hear (1950), The Black Rose (1950) and Father of the Bride (1950) – as well as Disney animations and current newsreels of the war (Pacific Stars and Stripes, 28 October 1950).

Onscreen entertainment was available to soldiers in the field almost every night throughout the three-year conflict. Troops swapped foxhole assignments and huddled inside abandoned railroad tunnels, burned-out houses and half-bombed buildings, enduring rain and freezing weather to catch a glimpse of films that were often simply projected onto walls or hanging bedsheets. In the words of one anonymous soldier, “When you go the movies over here, you get out of Korea for a couple of hours” (Pacific Stars and Stripes, 28 Aug 1951, p. 10). These daily Hollywood film screenings were a critical catalyst for raising the morale and national spirit of the troops on the front lines in Korea – an intriguing military strategy for bolstering the fight for democracy.

This was not the first time that Hollywood films played a vital role in military affairs in Korea. Within seven months of Korea’s liberation from Japanese colonial rule (1910-1945), and after the United States and Russia had carved the country in half, US film distributors rushed their most popular films to the southern half of the Korean peninsula. They were simply following the adage ‘trade follows the flag’ (Self, 1944, p. 6), even as Lt. General John R. Hodge and his US Occupation forces were disarming the Japanese military.2 Amid chaotic social, political and cultural change, local cinemas were inundated with a range of genre films from Hollywood. These were productions that the US Army Military Government in Korea (hereafter USAMGIK, 1945-1948) – under advisement from the Central Motion Picture Exchange, the U.S. film industry’s East Asian outpost – believed would assist them to reverse four decades of Japanese influence – in particular, to inculcate a sense of ‘liberty’ among Koreans. Instead of thinking and acting similarly to Japanese, Koreans were now expected to think about what ‘America’ and democracy had to offer them.

Despite the monumental size of this undertaking, most histories of the USAMGIK period such as Cumings (1997), McCune (1947), Meade (1951), and Oh (2002) lack a sustained discussion of this significant cultural aspect of the USAMGIK’s occupation strategy and its impact on local culture. These previous studies mostly focus on politics and the economy – not culture, and especially not film policy. Standard Korean film histories such as Lee and Choe (1998), Lee (2000), Kim (2002), Min, Joo and Kwak (2003), Yi (2003) and Cho (2005) are important, but they focus narrowly on the hardships and conflicts of Korean filmmakers in this era, and see Hollywood’s domination of Korean screens as a threat to local culture.

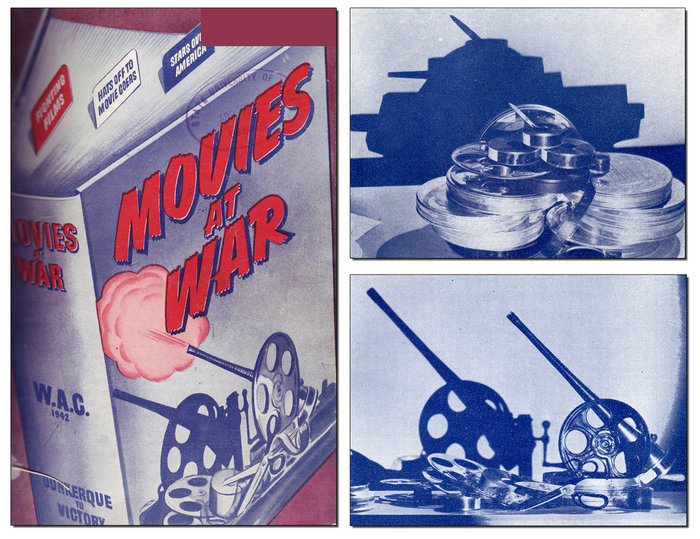

Until now, little has been published in either Korean or English about the hundreds of American films – made with ‘Hollywood’s cameras’, in contradiction to Japan’s now silenced ‘cannons’ (see Figure 1) – that were targeted explicitly at Korean audiences through advertisements in Korean-language newspapers. Indeed, this plethora of films was consumed by thousands upon thousands of local cinemagoers, including, of course, U.S. Army personnel.

Soon after liberation, local filmmakers and entertainment entrepreneurs became frustrated at the ‘undemocratic’ ways in which US occupation policy was restricting their activities. A wave of young and experienced filmmakers, many of whom who had grown up on a heavy diet of Hollywood films between 1926 and 1936, and who had gained valuable training making propaganda films for the Korean Colonial Government, were ready to explore realist aesthetics, film as art, and narratives that resisted Japanese power. Yet, USAMGIK film policy, which was a close copy of laws promulgated by the former colonial government, kept Korean filmmakers subservient, albeit temporarily, to an authoritative agenda that aimed at restoring democratic order to the region.

After 1945, members of the Korean film industry, in common with other cultural critics, expressed concern that Korea was simply being opened up to American goods and services, and Korean entrepreneurs were being sidelined. In fact, as this article shows, US film distributors (like the mining industry, for instance) were simply seeking to restore the level of business that they had enjoyed in Korea before the Colonial Government began suppressing American film culture and commerce with America more generally.

By analysing the impact of USAMGIK film policy, and the major themes of a cross-section of Hollywood films exhibited in Korea, we seek to explain the circumstances in which the project both failed and succeeded. Many of the spectacle films discussed here were used to evoke a sense of personal and political liberty, while distracting local audiences from the political turmoil of the period. With these themes in mind, this exploratory study provides new and important information about South Korea’s post-liberation film industry, which was desperate to break free from the legacy of 35 years of Japanese colonial rule.

First, however, a brief history of Hollywood’s dominance in the region is presented to help account for the influence of American film and American culture on Koreans.

Korea Awakening

Between 1926 and 1936, Hollywood experienced its first golden age in Korea (Yecies 2005). During this period, American films overwhelmingly dominated the Korean market. In 1932, films from the U.S. (calculated by length) amounted to 63 per cent of all film prints exhibited (Yecies 2008, p. 163). Hollywood had a much smaller market share in Japan, where about 70 per cent of all films screened were Japanese (Langdon 1934). During this decade, all major US film companies had direct distribution offices in Seoul, submitting around 5,700 prints to the Government-General of Korea’s film censorship office through local Japanese, Korean, American and Chinese representatives. An additional 640 Argentinian, British, Chinese, French, German, Italian and Russian films were divided evenly between Japanese and Korean representatives, both individuals and companies.

Among the most popular American film genres from the mid-colonial era were musicals, mysteries, action adventures, historical dramas, and gangster films. These were the genres described by Hollywood mogul Joseph M. Schenck, chairman of 20th Century-Fox, as making the big screen an ‘effective salesman of American products and the American way of life’ (Benham 1939, p. 410). Asia was not immune to this cultural allure.3

Perhaps surprisingly, colonial censorship restrictions posed little threat to this influx from Hollywood. From the evidence of film censorship statistics for the period between August 1926 and March 1935 – presented to the 69th Imperial Diet by the Library Section of the Bureau of Police Affairs of the Korean Colonial Government – censorship in Korea was strict and careful. Korean customs and cultural norms were seen as differing from those in Japan, and all films entering the country for public exhibition were assessed in light of this.4 Generally speaking, censorship laws restricted freedom of expression throughout the empire and suppressed films that critiqued Korean society under Japanese rule or glorified revolution.5 With these considerations in mind, the vast majority of Hollywood films submitted were approved with minor, if any, censorship changes, suggesting that the Government-General of Korea and Hollywood representatives maintained good relationships at this period.6 In terms of the total footage of all foreign films submitted, less than one-tenth of 1 percent was censored on the basis of being a threat to public morals.7

With access to an increasing number of foreign films, Koreans had the opportunity to escape from their colonial realities. In 1934, screenings of Hollywood films approved by the censor included I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang (1932), Frisco Jenny (1932), Tiger Shark (1932), Winner Take All (1932), Footlight Parade (1933), Gold Diggers of 1933 (1933), Captured (1933), 42nd Street (1933) and Little Giant (1933).8 These exciting and entertaining films appealed to people of all ages and literacy skills, as their narratives relied little on knowledge of English. Common themes found in these and other films mentioned in this article – too numerous to discuss in detail – included modernity, capitalism, justice and urban lifestyles, among a host of ‘American’ themes.9

Hollywood’s fortunes began to take a dive in 1935 when Governor-General Ugaki mandated that one-third of all screenings had to be of domestic films (defined as Japanese or Korean), thus increasing the barriers for foreign movies and precipitating a temporary boom in locally produced talkie films (Yecies 2008). Then, from the late 1930s, every scrap of film and every filmmaker in Korea was harnessed for Japan’s war-time film production project, which created a small number of feature-length propaganda films to coalesce public support for Japan’s war-time agenda, largely aimed at cultural assimilation. Representative Korean-Japanese co-produced films include Military Train (1938), Volunteer (1941), You and I (1941) and The Straits of Chosun (1943).10

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, strict censorship guidelines prevented Korea’s 120 cinemas from screening films from the U.S. and other Allied countries. Naturally, Hollywood distributors looked forward to the time when they could regain the market dominance in Korea that they had enjoyed during the middle years of the Japanese colonial period. The U.S. occupation of Korea was the solution – particularly with the re-opening of Hollywood distribution offices throughout the country from 1945.

Hollywood Rejuvenation

Following the end of the Pacific War, the United States and the Soviet Union divided Korea at the 38th Parallel: the southern and northern parts of Korea to be temporarily governed by the US and USSR respectively in order to facilitate the establishment of orderly government. The US interim government proclaimed its intention to transform the southern part of the Korean Peninsula into a ‘self-governing’, ‘independent’ and ‘democratic’ nation.11

During this time, four pivotal US players contributed to the re-invigoration of cinema culture in Korea: the Office of War Information (hereafter OWI),12 the Motion Picture Export Association of America (hereafter MPEA),13 the Central Motion Picture Exchange (hereafter CMPE)14 and the USAMGIK’s Motion Picture Section in the Department of Public Information (hereafter DPI). The chief role of the DPI was to monitor and improve public opinion towards the US and to democracy in general in Korea.

Before the end of the war, and before the OWI was incorporated into the US Department of State (hereafter US-DOS) in September 1945, the OWI’s Bureau of Motion Pictures had devised plans to continue ‘fighting with information’ in the post-war period (Barnes, 1943, p. 34). It established key CMPE outposts in Japan and the southern part of Korea, through which the U.S. government attempted to facilitate democracy and stability in the region. In addition to generating profits by distributing American feature entertainment films, the CMPE also distributed cultural and educational documentaries and newsreels, while the USAMGIK’s DPI promulgated film policy and initially oversaw film censorship during the US occupation.15 In US-controlled Korea, the Motion Picture Section was established in 1945 under the Public Information Bureau of the DPI. It had the clear objective of “disseminating information concerning American aims and policies, the nature and extent of American aid to Korea, and concerning American history, institutions, culture, and way of life.”16 OWI government information manuals make it clear that movies were viewed as ammunition for winning the war for democracy.

|

Figure 1. left: cover of the Movies at War, Vol. 1 pamphlet published by the War Activities Committee, Motion Picture Industry, New York City, 1942. The phrase ‘Cannon and Camera!’ appears above the bottom right image (p. 3). The phrase ‘Films Fight for Freedom’ appears below the top right image (p. 6). Images courtesy of Special Collections, University of Iowa Library.17 |

Hollywood films became a key vehicle for indoctrinating Koreans along these lines. In Germany, the US launched a similar project of transforming its former enemy into a democratic country through motion pictures. In short, Hollywood films were seen as quintessential vehicles for disseminating ‘American’ ideology as ‘democratic products’ (Fay, 2008, p. xix).

During the immediate post-war period, the USAMGIK’s propaganda operation in Korea was anchored by the dissemination of a flood of glamorous Hollywood ‘spectacle’ films across a range of genres, filling a noticeable void hitherto left empty by American, Korean, Japanese and other European films. As local film critics noted at the time, the sheer spectacle and extreme ‘foreignness’ of the Hollywood films on show enabled audiences to forget about the political turmoil going on around them (Lee, 1946, p. 4). The portrayal and promotion of modern Western city life in the films discussed in this article was an important facet of this process.

While the criteria used to select the American films distributed and exhibited in southern Korea appear somewhat random, many were Academy Award-winning (or nominated) films such as In Old Chicago (1937), Boy’s Town (1938), You Can’t Take it With You (1938), Suspicion (1941), The Sea Wolf (1941), Random Harvest (1942), Casablanca (1942) and Rhapsody in Blue (1945). In addition to having achieved popularity in the United States, these films presented well-dressed people scurrying along the skyscraper-lined, car-filled streets of Manhattan, Paris and other modern cities. Heterosexual coupling was depicted as a moral norm: lovers embraced openly on larger-than-life studio sets and natural locations alike. While many films contained strong moral themes affirming the final victory of justice and the importance of hope, others affirmed women’s (equal) rights, Christianity (religion) and patriotism. However, these themes were often expressed using less lofty motifs such as violence, vigilantism, public disorder, deception, desperation, suicide, theft, murder, killings, adultery and corruption.

Through the importation of Hollywood films from the mid-1940s, Korean audiences were exposed to large-scale, continuous visual and thematic representations that were totally foreign to their own cultural traditions. And, if the advertisements published in Korean in local newspapers are any indication, Korean audiences were the primary targets of these films. Generally speaking, Koreans had had long-standing Confucian traditions that required physical separation between noblemen and commoners on the one hand, and men and women on the other hand. Confucianism provided the foundational social, moral and legal guidelines and customs between people of all ages. Not only did cinema-going in this era enable all walks of life to mingle together in ways that were different from traditional Korean moral values, but the images, themes and motifs presented in the onslaught of spectacle Hollywood films, which was not a new phenomenon, did continually present ‘American’ situations that shook the roots of traditions and worried traditionalists.

Films such as Frank Capra’s You Can’t Take it With You, exhibited in April 1947, offered Korean audiences the opportunity to consider new ideas and social relations. In fact, Americans at home were told that the newly liberated countries of East Asia were ‘seeing, with awe and envy, the homes and clothes and motor cars of the world’s most prosperous and least-suffering people’ (Missoulian, 13 March 1945). In You Can’t Take it With You, an inter-class couple is presented as free to pursue an intimate relationship, resulting in a ‘happy ending’ that portrays wealthy people sacrificing their personal gains and championing community and family values. This was one Hollywood film among many that embraced themes of social mobility and change through marriage in the face of seemingly incompatible class relations, pitting ambition and wealth against happiness and social acceptance. Heterosexual coupling and marrying without parental or family consent was linked to the desire for social mobility through acquiring material wealth in a modern society.

However, seeing is a culturally constructed process, and Korean audiences saw more than they were perhaps intending to. In about half of all the American feature films exhibited at this time (and foreign films generally), what was seen on the screen was often at odds with the wholesome values ostensibly being promoted – these movies offered Koreans a mixed view of Western culture where open expressions of immoral behavior sat alongside purported democratic ideals. Property theft, fraudulent activities, malicious intent, crimes against individuals and authority figures and sexual contact of a kind eschewed in Confucian tradition filled local screens.

Fox’s In Old Chicago, produced by studio mogul Darryl F. Zanuck for almost $2 million and released in Korea in April 1946, exemplified the mixed messages received by Korean audiences from Hollywood. This film showcased major stars Tyrone Power, Alice Faye and Don Ameche, who deliver a dramatic message about overcoming poverty and fighting corruption. The film was inspired by the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, and showed how the city was rebuilt through determination and perseverance. In Old Chicago portrays an Irish family in the second half of the 19th century struggling to survive in a ‘modern’ society at a time when rough frontier towns were full of opportunity and the wealthy kept African-American house-servants. In the first 5 minutes of the film, as the family is travelling from the country to Chicago in their horse-drawn covered wagon, the father is killed while chasing a passing steam train – a sleek symbol of modernity. In the next scene, the following text appears onscreen: “Chicago – 1854. A City of easy money, easy ways, ugly, dirty, open night and day to newcomers from all parts of the world… a fighting, laughing, aggressive American city.”

The film is jam-packed with a wide range of positive and negative behaviors, including chivalrous men helping well-dressed women across muddy streets, unmarried couples kissing and hugging, fist fights and police raids in saloons, dancing girls in revealing clothes, and breaking and entering into private homes. Yet, as an overriding coda, In Old Chicago ends with the optimistic sentiment: ‘Out of the fire will be coming steel’—underlining the film’s projection of themes of righteousness, corruption and manifest destiny in the context of industrialization and American expansion. While the physical setting of the story perhaps shares some of the gritty feel of post-liberation Korean society, Asian audiences must have had difficultly finding the democratic message in a story where ‘moral turpitude’ is so openly and abundantly on display.

Ironically, although it was a hit on Korean screens, In Old Chicago was suppressed by the US Occupation authority’s Civil Censorship Detachment in Japan – not because of flagrant immorality, but because of its overt portrayal of political corruption.18 Hence, not all films bound for Korea via US distribution offices in Japan enjoyed public screenings, demonstrating differences in U.S. strategy in Korea and Japan. The difference reflects divergent objectives of the interim US governments in Korea and Japan. In Japan, the US had spent seven years creating and maintaining political stability in its former enemy. The process of ‘democratizing’ Korea was seen as a simpler task, achievable in just three short years and requiring less political vigilance.

In fact, USAMGIK was well aware of the criticism directed at the undesirable nature of many of these films. According to one report from mid-1947 submitted to the US-DOS, a committee of American educators that had conducted a formal survey of local attitudes in Korea was disappointed at the CMPE’s failure to offer appropriate films to Korean audiences.19

Hollywood Rollout

In February 1946, MPEA representatives, along with a local liaison officer who had previously worked for Paramount, one of the most active American distributors in colonial Korea, opened CMPE’s Korean branch in Seoul. From the outset, CMPE collected film rental fees from all exhibitors and documented daily box-office receipts and monthly attendance figures; it also monitored audience reactions to US films as well as those from other countries.20 Exhibitors were required to pay CMPE at least 50 percent of all box office revenues as part of the distribution deal, an arrangement which Korean exhibitors severely criticised.21

Despite sophisticated market analysis, USAMGIK did not immediately gain the upper hand in Korean cinemas.22 After liberation, and before cinemas could be renamed from Japanese to Korean names, a ‘black market’ emerged for the unofficial distribution and exhibition of Hollywood and Soviet films and those of other countries. Entrepreneurs and others interested in intellectual social debate, including communism, began exhibiting soi-disant illegal films. To assert their independence, and to make a quick profit during the exhibition vacuum left behind by the colonial regime, these entrepreneurs screened films such as Buster Keaton’s Steamboat Bill, Jr. (1928), The New Adventures of Tarzan (1935), and B-grade science fiction, gangster and action-adventure films such as Undersea Kingdom (1936), What Price Crime? (1935), Sea Devils (1937), and The Ware Case (1938). Political films such as Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympia (1936) and the Italian fascist propaganda film Lo Squadrone Bianco (1936) and the romantic drama Eravamo sette sorelle (1939) were also screened for the general public. Movies from France, such as Julien Duvivier’s monster film Le Golem (1936) and his gangster film Pépé le Moko (1937), and films from Argentina and China, were also exhibited.23

|

Figure 2. Advertisements. top: ‘The White Squadron’, New Corea Times 21 December 1945, p. 2; bottom: ‘Puerta Cerrada’, Hansung Daily 14 December 1946, p. 2; side: ‘Pépé le Moko’, Hansung Daily 27 October 1946, p. 3. |

Leftist entrepreneurs also stepped in the fill the gap in control of the film scene. Before USAMGIK had begun in earnest to assist the US film industry to spread ‘American’ views of so-called democracy and modernity via the exhibition of Hollywood films, other organizations such as the left-wing Chosun Film Federation (hereafter CFU) began holding screenings of Soviet feature films. In the early post-war period, CFU had stimulated debate in southern Korea about Korea’s political and social future by screenings films, such as Sergei Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible (1944), as well as Soviet newsreels (Armstrong 2003). They too were interested in developing new cultural ideas and attitudes that could help Korea move away from the militaristic ideology of the former Japanese colonial government.24 Yet, their activities were strongly opposed by the USAMGIK authorities – particularly given the proximity of Soviet forces in the northern part of Korea.25

USAMGIK eventually purged the marketplace of these ‘unwanted’ films under Ordinance No. 68, ‘Regulation of the Motion Pictures,’ promulgated in mid-April 1946. In October 1946, US Occupation forces also enacted Ordinance No. 115, which regulated the licensing of all commercial as well as educational and cultural films.26 On paper, these ordinances abolished most colonial film laws, such as the Peace Preservation Law of 1925, which has been referred to as Japan’s ‘domination over the soul’ (Lee 1999, p. 42). The Peace Preservation Law was a social policy instrument that rigorously detailed the cultural values and submissive behavior that imperial subjects were expected to show. Yet, in actuality, the two USAMGIK ordinances maintained the spirit of Japanese colonial censorship edicts, thus restricting Korean autonomy in the film industry.27

In April 1946, the month the first USAMGIK ordinance came into force, the first batch of authorized Hollywood films arrived in Seoul. Ironically, and seemingly haphazardly, they arrived with Japanese subtitles via CMPE-Japan (Christian Science Monitor 12 April 1946, p.19). A rueful prologue produced by the DPI’s Motion Picture Section appeared at the start of each of film, explaining the presence of these subtitles.28 In order to connect with local audiences, well-known Korean byeonsa (live narrators) were recruited to introduce each film and to explain how subsequent officially distributed films would contain either Korean subtitles or part-Korean dialogue.29

Almost immediately, these first Hollywood films made a splash in the marketplace as audiences lapped them up with enthusiasm, whether of not they understood them or appreciated the cultural values they contained (U.S. Embassy, Seoul 1950). According to the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers (hereafter SCAP) reports on USAMGIK activities in Korea, between 15 April and 31 May 1946, nearly 400,000 tickets to US feature films were sold, generating a turnover of Y4,000,000 (the equivalent of about $266,666). Subsequently, DPI’s Motion Picture Section stimulated a burst of censorship activity by approving 328 applications to screen American and other countries’ films, including a few from Korea.30 By June 1946 about 100 feature, short, documentary and newsreel films had been shown in southern Korean cinemas under the new regulations, leveling off thereafter to a monthly total of about 50 films, a flow that enabled CMPE to harmonize its activities with the politics of the occupation.

Police confiscated at least a dozen unapproved films from Korea, Germany, France and Italy in May 1946, and 9 cinemas across Seoul were shut down pending the arrival of approved films to exhibit (Donga Daily 5 May 1946, p. 2). The confiscation of unauthorized films removed competition and restored the kind of market dominance that Hollywood distributors had enjoyed in the colonial period between 1926 and 1936 (Yecies 2005). It also solidified MPEA’s growing footprint in post-war Asia. Prints that had not been approved by DPI were treated as black-market goods, and confiscated by USAMGIK police. Not only were pro-colonial and communist-oriented films, which violated the ideological spirit of the US Occupation, confiscated, but also any other films that might interfere with the monopoly that CMPE was attempting to build on behalf of the American film industry. Thus the decision to confiscate such films was based on both economic and cultural factors.

Dawn of Re-orientation

The documentaries and newsreels distributed by CMPE arrived in Korea along with a large number of US feature films which, like the former, were intended to serve the USAMGIK’s reorientation program. The larger list of films screened in April 1946 included Queen Christina (1933), Barbary Coast (1935), The Devil Doll (1936), Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936), Romeo and Juliet (1936), San Francisco (1936), The Great Ziegfeld (1936), The Buccaneer (1938), The Rains Came (1939), Golden Boy (1939), Honolulu (1939), The Under Pup (1939) and Abe Lincoln in Illinois (1940). These were ‘prestige pictures’ in the sense that they were ‘injected with plenty of star power, glamorous and elegant trappings, and elaborate special effects’ (Balio 1995, p. 180) – attractive packaging for presenting some of the core democratic reform values that the US government wanted for Korea.31

|

Figure 3. Advertisement. Top: ‘Honolulu’, Hansung Daily 14 July 1946, p. 4; bottom: ‘The Buccaneer’, The Korean Free Press, 13 May 1946, p. 2. Figure 4. Advertisements. left: ‘I Wanted Wings’ (1941), Jayu Shinmoon 4 May 1948, p. 2; middle: ‘Laura’ (1944), Daidong News 8 June 1948, p. 2. right: ‘Boom Town’ (1940), Jayu Shinmoon 27 August 1948, p. 2. |

Based on advertisements in Korean that appeared regularly in major local newspapers, a majority of the films screened at this time were talkies produced between the mid-1930s and early 1940s. Action-adventure and historical bio-pics were prevalent, followed by melodramas, screwball comedies, musicals, westerns, crime/detective thrillers, science-fiction and animated cartoons.32 These advertisements attempted to lure audiences with arousing drawings and silhouettes of film stars, action scenes and exotic locations, promoting all the glamour of American culture. They depicted dashing portraits of leading Hollywood stars including Robert Montgomery, Judy Garland, Bing Crosby, George Raft, Eleanor Powell, Richard Dix, Clark Gable (about to kiss Claudette Colbert in Figure 4 below) and Jean Arthur as a feisty cowgirl in Arizona (1940).

Often, the images in these advertisements revealed little about the themes treated in the film concerned. In contrast to the happy romantic image featured in the advertisement for MGM’s Boom Town reproduced below (Figure 5), the film portrays themes of frontier exploration and desire for material wealth, as well as jealousy and rivalry over women, and social mobility. These are all themes that would have appeared in striking contrast to the colonial ideology of the Japanese occupation, let alone the pre-colonial values to which Korean audiences were accustomed. At the same time, the graphic imagery of the advertisements attracted non-Korean-speaking US troops as well – a welcome secondary audience.

|

Figure 5. Advertisements. top: ‘Union Pacific’ (1939),Jayu Shinmoon 5 July 1948, p. 3; middle: ‘The Flame of New Orleans’, Jayu Shinmoon 5 July 1948, p. 3; bottom: ‘The Great Victor Herbert’, Jayu Shinmoon 14 July 1948, p. 3. |

As these advertisements show, many of these films carried the ‘heavy scent of “Americanism”’ (Yoshimi 2003, p. 434), portraying the United States as an exoticized and ‘glamorous elsewhere’. Ads for Westerns displayed men in ten-gallon hats either embracing a pretty woman or pointing a gun at the reader. Those for romantic dramas and musicals, such as Romeo and Juliet (1936, exhibited in July, September and December 1946 and in October 1947), I Wanted Wings and Honolulu showed scantily-dressed women and couples in passionate embraces. These and other films portraying ‘modern life’ showcased ‘film stars, dance crazes, general oddities and glamorous strangeness’ (Vieth 2002, pp. 23-24), and the newspaper ads faithfully reflected this. Although exhibitors promoted programs that mixed features with shorts and live musical and/or theatrical performances, a surfeit of Hollywood films left little room for the exhibition of films from Korea and elsewhere: movies which might have offered alternative views of ‘America’ – and modernity, for that matter.

The USAMGIK Legacy

The question remains how successfully American films distributed and exhibited in the southern half of the Korean Peninsula meshed with USAMGIK’s occupation strategy. The films selected originated from a variety of sources, including film distributors in Shanghai and U.S. film distributors’ vaults in colonial Korea that were impounded by the Japanese authorities after Pearl Harbor. Yet, regardless of the origins of these prints, the US film industry was able to profit from the exhibition of older and recycled films while at the same time exploiting them for their cultural contents. In fact, before appearing in Korea, most if not all these feature films would have undergone the self-censorship process implicit in Hollywood’s Motion Picture Production Code. This industry initiative attempted to ensure that stories and scenes contained appropriate content for domestic viewers. USAMGIK would no doubt have been confident that these star-driven films – often in the running for Oscars – upheld the kind of moral values and accurate portrayals of (American) society that would not offend Korean audiences.

However, as we have seen, while many CMPE films approximated this model, an equal number offered a different view of America: one that depicted opulence, feisty and independent female characters, unrestrained love-making, violent themes and an exotic cultural milieu that was both thrilling and dangerous – as newspaper advertisements containing guns attest. This suggests that CMPE was keen to select sensational films that would bring both locals and Occupation troops to the cinemas in droves, without carefully distinguishing between these two audiences.

The portrayal of gender themes especially was potentially problematic. Otto Preminger’s film-noir mystery-romance Laura portrays the female protagonist as a successful and savvy advertising executive. Her traits and abilities are continually questioned in the context of the ‘proper’ conduct of women and class boundaries.33

We have no way of knowing whether the popularity of the films discussed in this article equated with their success in implanting American ideologies of democracy and gender equality in Korean audiences. DPI officials may have been preoccupied with larger issues or lacked sufficient motivation to gain a deeper understanding of Korean culture and the aspects of American movies that would appeal to Korean audiences. On the face of it, it should not have been too difficult for the US authorities to select for general release films with a predominantly positive message while winnowing out their less edifying counterparts. Films such as Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939), The Life of Emile Zola (1937), Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, Penny Serenade (1941), The Rains Came and Random Harvest were better vehicles for showcasing democratic and other ‘wholesome’ ideals and values that represented the best of what ‘America’ had to offer. However, an equal number of films evidently catered to US troops rather than Koreans.

Clearly, however, there was a limit to what the USAMGIK and CMPE could achieve in the short time at their disposal. Nor were CMPE and the US film industry the only parties at fault. Other foreign films such as the French gangster film Pépé le Moko (1937) and the musical comedy Avec Le Sourire (1936), Monte Carlo Madness (1932), Burgtheater (1936) and the sex and horror film Alraune (1928) from Germany, as well as Puerta Cerrada (1939) from Argentina, titillated audiences with provocative images both onscreen and in newspaper advertisements. DPI failed to censor objectionable or obscene content from these foreign films as it was more concerned with blocking films with communist sympathies and any Hollywood films obtained through unofficial – that is, non-CMPE/MPEA – channels. As a result, audiences were freely exposed to films like Pépé le Moko, set in Algiers’ seedy casbah underworld where gunfights are common, and a melting pot of gypsies, Slavs, blacks, Arabs, homeless people, Sicilians, Spaniards, prostitutes and corrupt officials stands in stark contrast with the (apparently civilized) French colonial authorities. The film’s negative ending depicts the protagonist’s suicide after losing the chance to develop love and trust with his girlfriend (who betrays him), and thus, to redeem himself.

Hence, as we have already suggested, US involvement in developing a new age of cinema culture in liberated Korea was more complex than previous studies have indicated. Whereas American films received a warm reception in Japan into the early 1960s (MPEAA 1961), in Korea they experienced tougher market restrictions after President Rhee took office in 1948. Although the general public was enthusiastic about Hollywood ‘spectacle films’, intellectuals and the Korean government saw American films (and USAMGIK film policy) as a threat to Korean culture and tradition, and a hindrance to developing a local industry. Despite their entertainment value, American films that promoted themes of violent and anti-social behavior, and frequently portrayed Western notions of ‘gender equality’, had unintended consequences in Korea.

Political turmoil on the ground posed difficult challenges for US occupation forces and for USAMGIK’s attempts to execute a highly organized cultural re-orientation campaign. As a result, US occupation authorities likely misunderstood local concerns and underestimated the impact that thirty-five years of Japanese colonialism had had on Korea. Nevertheless, USAMGIK’s aim of reorientating Koreans away from the legacies of the former Japanese colonial regime was achieved with surprising ease by allowing hundreds of Hollywood spectacle films back into the region. Their contents could not have differed more from the propaganda and cultural films that the Korean Colonial Government had obliged audiences to watch (and Korean filmmakers to make) between 1937 and 1945. In pursuing this course, USAMGIK had indeed disarmed Japan’s ‘cannons’ with Hollywood’s cameras.

However, both domestic audiences and US Occupation forces were too distracted by the political situation for a comprehensive Hollywood re-orientation project – combined with other US-controlled media such as radio and print propaganda – to generate new cultural ideas and ideals. Ultimately, the procession of glamorous images and stirring stories in films and other media kept the post-liberation euphoria flowing until USAMGIK could stabilize the southern half of the Korean Peninsula. While CMPE’s films may not have had the immediate and solid effect on Koreans for which USAMGIK had hoped, the entertainment and exoticism associated with ‘America’ certainly lingered in the minds of Korean audiences.

At the same time, although USAMGIK saw all its activities as contributing to the growth of democracy, it hardly needed to work as diligently as it did to generate ‘American’ attitudes among Koreans because Hollywood films (and therefore, American culture) had only been suppressed for 7 or 8 years before 1945. In addition, traditional Korean culture had never been completely suppressed, despite the colonial authority’s efforts to implement Japanese language into everyday learning and communication.

Eventually, a steady diet of Hollywood productions – regardless of whether their narrative styles fell outside the Motion Picture Production Code guidelines – proved too much for Korean audiences including president-in-waiting Syngman Rhee. According to an anonymous article in the right-wing newspaper Chung Ang Shinmoon (31 March 1948), American pictures seduced Koreans with the ‘thrill of murder and gangsterism, with fickle and promiscuous love, with frenzied jazz, and with the pleasures of life in foreign countries’, thus seriously affronting Korean cultural norms.34 Other critics were concerned that Koreans were mindlessly consuming the eroticism, glamour and fantasy depicted in American films without considering the massive gulf between everyday life and culture in the US and in Korea (Lee, Kyunghyang Daily 30 October 1946, p. 4). The open expressions of sexuality and boisterous behavior portrayed in these films were seen by American education specialists (on a formal fact-finding visit to Korea) as culturally insensitive and potentially injurious to Korea’s Confucian traditions and national pride (USAMGIK 1947).

By March 1949, only six months after the end of the USAMGIK period and establishment of the Republic of Korea, Hollywood’s economic stronghold in the southern part of Korea was already slipping. President Syngman Rhee was developing regulations to limit the number of imported American films – partly to assist the rebirth of a domestic film industry and partly to limit the public’s exposure to what was seen as objectionable content (US Embassy, Seoul 1949).35

The proponents of such views were more interested in seeing and producing films with more appropriate and edifying themes to counter those embedded in the military propaganda films produced during the last few years of the Japanese colonial period and the perceived vulgarity and objectionable content of Hollywood films. After years of suppression by the Japanese colonial authorities, workers in the Korean film industry were genuinely looking forward to the stimulation of the domestic industry that USAMGIK was supposed to have offered after liberation. However, the reality of CMPE’s market dominance quickly tarnished these hopes. As one newspaper editor summed up the issue early on: “The CMPE’s coming to Korea was not to fertilize Korean cinema, but to plant a strong tree of the American cinema over the top of the sprouting Korean cinema” (Seoul Newspaper 26 May 1946, p. 4).

Nonetheless, the domestic industry revived as local filmmakers consolidated their production skills and re-used equipment formerly owned by the consolidated Chosun Film Production and Distribution Co. that the Colonial Government created between 1941 and 1942. It was also happy to answer USAMGIK’s call for the production of Liberation News shorts and a small number of ‘Liberation’ feature films. As a result of these and other factors, the foundations of a national film industry were laid.

Although progress was disrupted by the civil war, the Korean film industry blossomed both in terms of its size and of the quality and number of films made in the mid-1950s, starting with the release of Lee Kyu-hwan’s The Tale of Chunhyang (1955) and Kim Ki-young’s Yang san Province (1955). Invitations to international film festivals increased proportionately. The 111 films made in 1959 constituted a dramatic increase over the mere 15 films made in 1955 (KMPPC, 1976, p. 47).

Although the full impact of USAMGIK’s re-orientation film programme on Korea is likely to remain unknown, a deeper understanding of its policy underpinnings, execution and pitfalls provides new insights into how this cultural project contributed, at least in theory, to the ‘Americanizing’ of the region. Ironically, South Korea’s love affair with Hollywood feature films revived during the 1950s and 1960s, a process well-documented in McHugh and Abelmann (2005). The continuing popularity of Hollywood genre conventions, iconography and the star system, conspicuous in many Golden Age classics from Madame Freedom (1956) to Barefoot Youth (1964), suggests that the Hollywood films distributed during the USAMGIK period may have had a longer-term cultural impact than can be gleaned from distribution and exhibition statistics alone.

Brian Yecies is Senior Lecturer in Media and Cultural Studies and the Co-convenor of the Bachelor of Communication and Media Studies degree at the University of Wollongong. His research focuses on film policy, the history of cinema, and the digital wave in Korea. He is a past recipient of research grants from the Asia Research Fund, Korea Foundation and Australia-Korea Foundation. His book Korea’s Occupied Cinemas, 1893-1948 (with Ae-Gyung Shim), which is supported by the Academy of Korean Studies, is forthcoming in the Routledge Advances in Film Studies series.

Ae-Gyung Shim teaches part-time in the Bachelor of Communication and Media Studies degree program at the University of Wollongong, and is an avid cook. Her PhD thesis, written while studying in the School of English, Media and Performing Arts at the University of New South Wales, focuses on the transformation of film production, direction, genre and policy in South Korea during the 1960s golden age.

Recommended citation: Brian Yecies and Ae-Gyung Shim, “Disarming Japan’s Cannons with Hollywood’s Cameras: Cinema in Korea Under U.S. Occupation, 1945-1948,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 44-3-10, November 1, 2010.

References

Armstrong, C 2003, ‘The Cultural Cold War in Korea, 1945-1950’, Journal of Asian Studies 62:1, pp. 71-99.

Balio, T 1995, Grand Design: Hollywood as a Modern Business Enterprise, 1930-1939, vol. 5, History of American Cinema Series, University of California Press, Los Angeles.

Barnes, J 1943, ‘Fighting with Information: OWI Overseas’, The Public Opinion Quarterly 7:1, pp. 34-45.

Benham, A 1939, ‘The “Movie” as an Agency for Peace or War’, Journal of Educational Sociology 12:7, pp. 410-417.

Caprio, M 2009, Japanese Assimilation Policies in Colonial Korea, 1910-1945, University of Washington Press, Seattle.

Cumings, B 1997, Korea’s Place in the Sun: A Modern History, W.W. Norton, New York.

Eckert, CJ, Lee, K, Lew, YI, Robinson, M and Wagner, EW 1990, Korea Old and New: A History, Seoul, Published for the Korea Institute, Harvard University by Ilchokak.

Farhi, P 1988, ‘Seoul’s Movie Theaters: Real Snake Pits?’, The Washington Post (17 September): 14.

Fay, J 2008, Theaters of Occupation: Hollywood and the Reeducation of Postwar Germany, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis.

Hicks, OH 1947, ‘American Films Abroad’, Journal of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers 49:4, October, pp. 298-299.

Hirano, K 1992, Mr Smith Goes to Tokyo: Japanese Cinema Under the American Occupation, 1945-1952, Smithsonian Institute Press, Washington D.C.

Iwasaki, A 1939, ‘The Korean Film’, Cinema Year Book of Japan 1939. International Cinema Association of Japan and the Society for International Cultural Relations, Tokyo, pp. 64-65.

Johnston, RJH 1945, ‘Japanese Put Out Of Korea Rapidly’, New York Times 10 October, p. 7.

Joongoi Daily 1946, ‘Film Review: The Rains Came/20th Fox’, Joongoi Daily 9 May, p. 2.

Kim, HJ 2002, ‘South Korea: The Politics of Memory’, in Being & Becoming: The Cinemas of Asia, Aruna Vasudev, Latika Padgaonkar, and Rashmi Doraiswamy eds, Macmillan India, Delhi, pp. 281–300.

Kitamura, H 2007, ‘Exhibition and Entertainment: Hollywood and the American Reconstruction of Defeated Japan’, Local Consequences of the Global Cold War, Jeffrey A. Engel, ed, Stanford University Press, Washington D.C., pp. 33-56.

Kitamura, H 2010, Screening Enlightenment: Hollywood and the Cultural Reconstruction of Defeated Japan, Cornell University Press, Ithaca.

KOFA. Korean Cinema through Newspaper Articles: 1945-1951 (Sinmungisa ro bon hanguk yeonghwa: 1945-1957). Seoul: Gonggan gwa saramdeul, 2004.

Korean Motion Picture Promotion Corporation (KMPPC) 1976, Korean Film Material Collection, KMPPC, Seoul.

Koppes, C and Black, G 1987, Hollywood Goes to War: How Politics, Profits and Propaganda Shaped World War II Movies, University of California Press, Berkeley.

Langdon, WR 1934, ‘Chosen (Korea) Motion Picture Notes’, US-DOS, 23 March. File 895. Records of the US-DOS Relating to the Internal Affairs of Korea, 1930-1939, The National Archives at College Park, Maryland (hereafter NARAII).

Lee, C 1999, ‘Modernity, Legality, and Power in Korea Under Japanese Rule’, Colonial Modernity in Korea, Shin G and Robinson, M eds., Harvard University Asia Center, Cambridge, MA., pp. 21-51.

Lee, H 2000, Contemporary Korean Cinema: Identity, Culture, and Politics, Manchester University Press, Manchester.

Lee, TW 1946, ‘How are we going to watch US films’, Kyunghyang Daily, 31 October, p. 4.

McHugh, K. and N. Abelmann (eds.). 2005, South Korean Golden Age Melodrama: Gender, Genre, and National Cinema, Wayne State University Press, Detroit.

McCune, GM 1947, ‘Post-War Government and Politics of Korea’, The Journal of Politics 9:4, pp. 605-623.

Meade, EG 1951, American Military Government in Korea, King’s Crown Press, New York.

Min, EJ, Joo, JS and Kwak, HJ 2003, Korean Film: History, Resistance, and Democratic Imagination, Praeger, Westport.

Motion Picture Export Association of America (MPEAA) 1961, ‘Japan Country Fact Book’, USC-Warner Bros. Archives, Japan File #16520B.

Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA) 1942, ‘Motion Pictures in Wartime’, Film Facts, 1942: Twenty Years of Self Government, New York. Record Group (hereafter cited as RG) 208, Records of the OWI, Records of the Historian Relating to the Domestic Branch, 1942-1945, Box 3, Entry 6A, NARAII.

Oh, BBC (ed.) 2002, Korea Under the American Military Government, 1945-1948, Praeger, Westport, CT.

Robinson, M 1984, ‘Colonial Publication Policy and the Korean Nationalist Movement’, Myers, R and Peattie, M eds., The Japanese Colonial Empire, 1895-1945, Princeton University Press, Princeton, pp. 312-343.

Self, SB 1944, ‘Movie Diplomacy: ‘Propaganda’ Value of Films Perils Hollywood’s Rich Markets Abroad’, Wall Street Journal, 16 August, p. 6.

U.S. Embassy, Seoul 1949, ‘Dispatch No. 247: South Korean Motion Pictures’, 4 May, RG59, US-DOS Decimal File 1945-49, Box 7398, NARAII.

U.S. Embassy, Seoul 1950, ‘Dispatch No. 657’, 2 January, US-DOS, RG59, Decimal File 1945-49, Box 7398, NARAII.

USAMGIK 1947, ‘Report of the Educational and Informational Survey Mission to Korea’, 20 June, US-DOS, RG59, Decimal File 1945-49, Box 7398, NARAII.

Vieth, E 2002, ‘A Glamorous, Untouchable Elsewhere: Europe’s American Dream in World War II and Beyond’, International Journal of Cultural Studies 5:1, pp. 21-44.

Yecies, B 2005, ‘Systematization of Film Censorship in Colonial Korea: Profiteering From Hollywood’s First Golden Age, 1926–1936’, Journal of Korean Studies 10:1, pp. 59-84.

Yecies, B. 2008, ‘Sounds of Celluloid Dreams: Coming of the Talkies to Cinema in Colonial Korea’, Korea Journal 48:1, pp. 16-97.

Yecies, B and Shim A (forthcoming), Korea’s Occupied Cinemas, 1893-1948, Routledge Advances in Film Studies, New York.

Yi, HI 2003, ‘The Korean Film Community and Film Movements During the Post-liberation Era’, Traces of Korean Cinema From 1945 to 1959, Korean Film Archive, Seoul, pp. 11-89.

Lee, YI and Choe YC 1998, The History of Korean Cinema, Jimoondang, Seoul.

Yoshimi, S 2003, ‘“America” as Desire and Violence: Americanization in Postwar Japan and Asia during the Cold War’, trans. David Buist, Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 4:3, pp. 433-450.

Notes

1 The authors acknowledge the generous research support from the Academy of Korean Studies, Asia Research Fund, and Korea Foundation. Invaluable guidance was provided by librarians and archivists at the University of Maryland-College Park (Gordon W. Prange Collection), National Archives (NARAII, College Park), University of Wisconsin-Madison, United Artists Collection State Historical Society of Wisconsin, Special Collections in the University of Iowa Library (Papers of the Victor Animatograph Corp.), Cinema/Television Library, Korean Heritage/East Asian Library and Warner Bros. Archives at USC, Arts Special Collections at UCLA, and the Margaret Herrick Library-Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in Los Angeles. Special thanks goes to Mark McLelland, Mark Caprio, Mark Morris, and Hiroshi Kitamura for valuable comments on earlier drafts.

2 An insightful article about USAMGIK by Lt. General Hodge appears as “With the U. S. Army in Korea”, National Geographic Magazine, June 1947, pp. 829-840.

3 The comprehensive Korean Cinema: From Origins to Renaissance (2007), by the Korean Film Council, has grossly underestimated Hollywood’s activities in colonial Korea and its long-term links to the US film industry’s stronghold in the Asian region.

4 Censorship statistics cited in this article come from: “Table of Censored Motion Picture Films, 1 August 1926 to 31 March 1935” (Katsudō shashin [firumu] ken’etsu tōkeihyō, Taishō jūgonen hachigatsu tsuitachi kara Shōwa jūnen sangatsu sanjūichinichi made), Sixty-ninth Imperial Parliament Document (Dairokujūkyūkai Teikoku Gikai Setsumei shiryō), Library Section of the Bureau of Police Affairs, Korean Colonial Government (Chōsen Sōtokufu Keimukyoku Toshōkan Teikoku Gikai Setsumei shiryō), Serial# CJA0002448, File# 101-7-1-2, Ministry of Government Administration and Home Affairs, Government Archives and Records Service, Daejon, Korea (hereafter cited as Archives and Records Service); and “Table of Censored Motion Picture Films, 1 April 1935 to 31 March 1936” (Katsudō shashin [firumu] ken’etsu tōkeihyō, Shōwa jūnen shigatsu tsuitachi kara Shōwa jūichinen sangatsu sanjūichinichi made), Sixty-ninth Imperial Parliament Document (Dairokujūkyūkai Teikoku Gikai Setsumei shiryō), Library Section of the Bureau of Police Affairs, Government-General of Chōsen, File #CJA0002471, Archives and Records Service

5 One of the primary aims of the Library Section was to suppress material regarded as promoting such subversive themes, in particular Korean independence and communism – rather than block foreign films outright.

6 Although during this decade minor cuts were made to Universal, Fox and Paramount films (75, 63, and 51 cuts respectively) for allegedly violating public peace and safety, only 10 (out of a total 3599) individual reels from Paramount were completely rejected by the censors, while Universal and Fox suffered no rejected reels.

7 Between 1926 and 1935, two-thirds of all Universal films submitted for censorship approval to the Library Section of the Bureau of Police Affairs were handled by Korean distributors/importers, and two-thirds of all Fox films were represented by Japanese. Nearly all Paramount films from this decade were represented by Koreans.

8 United Artists collection, Series 1F Box 5-5, State Historical Society of Wisconsin.

9 In 1932 alone, around one in every three Koreans (of all ages) was watching movies mainly made in America and Japan, but also including films from other countries (Langdon 1934).

10 During this time, and through the narratives in these films, the Korean Colonial Government intensified its encouragement for Koreans to support Japan’s colonial (and nationalistic) agenda, which was formalized in 1938 under the naisen ittai (naeseon ilche in Korean), or ‘Japan and Korea as One Body’ assimilationist policy (Eckert, 1991, p. 236).

11 Records of the US Department of State relating to the internal affairs of Korea, 1945-1949, Department of State, Decimal File 895, Reel 5, ‘US role in Korea’, National Archives at College Park, Maryland (hereafter cited as NARAII).

12 The OWI had been developed in the United States in mid-1942 to coordinate the mass diffusion of media and information at home and abroad through multiple government departments. To remain as close to the American film industry as possible, OWI operated a branch office in Hollywood. It published government information manuals that advised industry representatives about how ‘the motion picture should be the best medium for bringing to life the democratic idea’ – that is, American notions of ‘freedom’.

13 MPEA was formed in June 1945 under the Webb-Pomerene Act in order to support the US economy and to promote world peace. The organization developed influential trade strategies that successfully overcame foreign market barriers and increased distribution profits for its member companies.

14 In early 1946 OWI and MPEA formally coalesced under the name of the Central Motion Picture Exchange. Among other roles, CMPE was charged with controlling the distribution rights for MPEA members’ films throughout Asia.

15 See ‘Operational Guidelines for the Distribution of O.W.I. Documentaries and Industry Films in the Far East’, 22 December 1944, Records of the OWI, Records of the Historian Relating to the Overseas Branch, 1942-1945, RG 208, Box 2, Entry 6B, NARAII.

16 Department of State Decimal File 1945-1949, RG59, BOX 7398, ‘Report of the Educational and Informational Survey Mission to Korea’, Seoul, Korea 20 June 1947, p30. NARAII.

17 This material is also contained in: Records of the OWI, Records of the Historian Relating to the Domestic Branch, 1942-1945, RG 208, Box 1, Entry 6A, NARAII.

18 “A Manual for Censors of the Motion Picture Department”, RG331, Box 8603, Folder 7, SCAP Records, NARAII.

19 In its report, the committee stated: “The only American films generally available to Koreans are old feature films distributed by the Korean branch of the Motion Picture Export Association. These are of inferior quality and are completely inappropriate vehicles for presenting American culture in Korea. As in other oriental countries, motion pictures are enthusiastically received by the Korean public.” See Report of the Educational and Informational Survey Mission to Korea, 20 July 1947, pp 35-36. US-DOS, Decimal File 1945-49, RG59, Box 7398. NARAII

20 See ‘Memorandum’, from M. Bergher to the Chief of the C. I. & E., 12 April 1946. RG331, Box 5062, Folder 15, ‘Motion Pictures, Sep 1946 – Dec 1947’, and Box 1020, Folder 9, ‘Central Motion Picture Exchange’, SCAP Records, NARAII.

21 According to the former manager of the Chosun Film Company, profit-sharing arrangements had been better for Korean exhibitors under Japanese rule, when they had been only 35-40 percent. For older film industry operatives in Korea, the CMPE’s higher fees were an unwelcomed challenge (Joongoi Daily 19 April 1946, p. 4).

22 Systematic market intelligence was supplied to the Chief Film Officer of DPI, which forwarded it to the OWI Motion Picture Bureau in New York for discussion among film industry executives. The CMPE’s data collection processes helped them cultivate Korean and Japanese markets for future MPEA domination.

23 It is important to list these titles here because their screenings demonstrate a sense of initiative among Koreans that USAMGIK eventually blocked. Their exhibition also reveals a greater diversity in the national cinema scene in the earliest stages of the US occupation than was the case with Japan, as discussed in Hirano (1992) and Kitamura (2007; 2010).

24 Caprio (2009) suggests that Japan’s assimilation project failed because there was no real intention on the Japanese side to allow Koreans to be fully assimilated into Japanese culture. Nevertheless, it seems the colonial authorities were at least successful in creating a fantasy world where Koreans could act more like their fellow Japanese as a result of their indoctrination in Japanese language, education, customs and culture.

25 Before it was silenced, and before restrictive film regulations were enacted, CFU ran articles in the daily press criticizing CMPE for its close ties to USAMGIK and its monopoly of the local exhibition market. Other groups attempted to screen colonial-era films such as Crossroads of Youth (1934) and the propaganda film Military Train (1938). However, USAMGIK forces quickly confiscated these and all other films not approved by DPI in advance of their public exhibition.

26 General Headquarters, SCAP, Commander in Chief, U.S. Army Forces, Pacific, 1946, ‘Monthly Summation No. 8’, US Army Military Government Activities in Korea, Tokyo, May, p. 88; and 1946, ‘Monthly Summation No. 13’, October, p. 81.

27 The USAMGIK’s new powers soon became apparent. Its censorship process required 3 copies of every screenplay in English to be delivered to it, regardless of the language spoken in the film in question. All films, including those already in Korea, were subject to censorship approval, a rule which attracted immediate complaints from Korean filmmakers and other industry businesspeople that found translation costs prohibitive (Seoul Newspaper 5 May 1946, p. 5; Jayu Newspaper 5 May 1946, p. 3.)

28 RG331, Box 5062, Folder 15C “Motion Pictures, Sep 1946-Dec 1947”, SCAP Records, NARAII.

29 Shipping this first batch of prints to Korea was no doubt seen as efficient and economical, suggesting that the US authorities had sent whatever prints were available – probably stock abandoned by US distributors during the war. This implies a limited effort with limited resources to control the film market in Korea – in contrast to the situation in Japan discussed elsewhere by Kitamura (2007; 2010).

30 General Headquarters, SCAP, Commander in Chief, US Army Forces, Pacific, 1946, ‘Monthly Summation No. 9’, US Army Military Government Activities in Korea, Tokyo, June, p. 79; and 1946, ‘Monthly Summation No. 11’, August, p. 88. Our understanding is that the exchange rate between USD and Japanese Yen (in Japan) was set at Y15 per $1 in the wake of war in September 1945, and the inflation of the early postwar economy led to a rate change to Y50 per $1 in 1947. Eventually, this was capped at Y360 per $1 in 1949.

31 Whether or not these big-budget spectacle films successfully embodied or transmitted democratic ideology and other ‘American’ ideals to Koreans, they were regularly screened over the course of the USAMGIK period – each about once every six months (for several days at a time).

32 These and other films distributed by CMPE had little competition in the entertainment field, apart from frequent live theatrical and musical performances and a few screenings of older Korean films such as Ahn Seok-young’s 1937 talkie feature The Story of Shim Cheong, Na Un-gyu’s silent classic Arirang (1926), and Choi In-gyu’s colonial propaganda film Angels on the Streets (1941). The evidence suggests that the exhibition of a small number of Korean films was allowed by USAMGIK to placate domestic criticism of CMPE’s ‘anti-democratic’ practices. Arirang was screened multiple times, including at the Jeil Cinema (Segye Daily 9 April 1947, p. 2) and on 28 July 1948 at the Chosun Geukjang (Jayu Shinmun 28 July 1948).

33 And on the subject of portrayals of alternative female sexuality, one may ask how a pre-Code film with a lesbian subtext such as Queen Christina could be seen as exemplifying American moral and cultural values.

34 This quote, an English translation of the original article, is contained in: ‘Dispatch No. 80: Korean Opposition to American Motion Pictures’, 7 April 1948. Records of the US-DOS relating to the internal affairs of Korea, 1945-1949, microfilm reel #7, Decimal File 895. NARAII.

35 US film industry representatives were anticipating a maximum of only seventeen films allowed into Korea per year.