Gavan McCormack

Three months before he became Prime Minister, in July 2006 Abe Shinzo published his political manifesto, under the title Utsukushii kuni e (Towards a beautiful country). It is well known that Abe’s sense of beauty involves a denial of the darkest aspects of wartime history and insistence on compulsory love of country, and that he is committed to revision of the country’s basic institutions accordingly. But the fundamental changes in the country’s military posture, and especially in its relationship with the United States, have received less attention. Here we consider evidence of a new domestic role for the Self Defense Forces (SDF) as enforcer of unpopular policies, and the implications of a new law to facilitate US military reorganization. Okinawa is at the center of both.

On 11 May 2007, the Japanese Maritime Self-Defense Force’s Bungo minesweeper set sail from the naval port of Yokosuka for Okinawa, under orders from Prime Minister Abe to assist in a “preliminary” survey of the ocean floor of Oura Bay, where his government plans to construct a state-of-the-art base for the American marines. Under cover of darkness, divers from the Bungo carried out their seabed survey and the ship then withdrew. The operation took only a few days, and neither the media nor the local and national groups opposing the base caught sight of the Bungo or its divers.

The MSDF Bungo in 2004 in the Persian Gulf prepares to refuel the USS Patriot (right)

Insignificant, one might say, yet it would be a mistake to dismiss it as such for the event reveals much about the character of Abe’s Japan. In 2005 and 2006, the US and Japanese governments drew up a major agreement on the reorganization of US forces in Japan.[1] It was a complex deal, but the bottom line was integrating the forces of the two countries, especially their intelligence and command functions, and transforming Japan’s “Self-Defense Forces,” whose justification had hitherto rested on their role in the defense of Japan “against direct or indirect aggression” into a junior partner role of the US in the global war on terror, as the “Great Britain of East Asia.” Japan was to meet the cost of the reorganization, including six and a half billion dollars just for re-locating 8,000 marines and their families to Guam (even building houses and recreational facilities there for them) and an unspecified sum for the construction of the new base in Okinawa (for which estimates range in the ten billion dollar plus range), quite apart from the institutionally entrenched subsidies that have been going on for over thirty years, and will continue.

Despite Japan’s “pacifist” constitution, which Prime Minister Abe is moving aggressively to consign to the dustbin of history, Japan is the world’s No 3 or No 4 military power. In naval terms it is probably No 2, its Maritime Self Defense Force having 45,842 sailors, 152 major vessels including four Aegis destroyers (cost about three to four billion dollars each), 54 convoy ships (conventional destroyers), 16 submarines, and multiple anti-submarine, reconnaissance, supply, rescue and minesweeping vessels (such as the Bungo) – pretty much everything but aircraft carriers. For over a decade, the Japanese government has worked to soften Japanese public opinion about its steady military expansion program by stretching the constitution to the limits, sending the SDF to participate, first in UN peace-peeking operations, and then in US-led, “Coalition of the Willing,” operations in the Indian Ocean and Iraq. But that has not been enough to satisfy the Pentagon, which now clearly wants Japan to remove the remaining constitutional and legal shackles from this formidable force so that it can be fully incorporated under US command throughout the “Arc of Instability.”

A raft of legislation – ultimately intended to include revision of the constitution – became necessary to implement the various new Japanese commitments. As the Bungo sailed, the Diet was considering a bill “to facilitate the implementation of plans to realign US forces in Japan” (Beigun saihen tokusoho), which it passed a few days later, on 23 May. [2]

The 23 May law is designed to step up the pressure on local governments by financially rewarding those who submit to the paramount will of the national government and accept the primacy of defense and US considerations over civil and democratic ones, while punishing those who give priority to local democratic opinion and processes. Cooperative local governments are to be given substantial sums, in tranches at the various stages of specific projects – consent, survey, construction, completion. It was designed with Okinawa particularly in mind, but other localities too now face a panoply of financial and other interventions.

The Oura Bay/Cape Henoko base whose construction the Abe government is so anxious to advance that it sent in the SDF has long been a running sore in the US-Japan relationship.[3] In 1996 such a base, at first called a “heliport” was proposed as part of the deal between the Hashimoto and Clinton administrations to allow the return to Japan of the Futenma marine base in central Okinawa. Futenma sits incongruously and threateningly in the middle of the bustling town of Ginowan. Henoko – the chosen replacement site, was a sleepy fishing hamlet, long coveted by the Pentagon as part of its plan to rationalize and concentrate its forces in the north of the island.

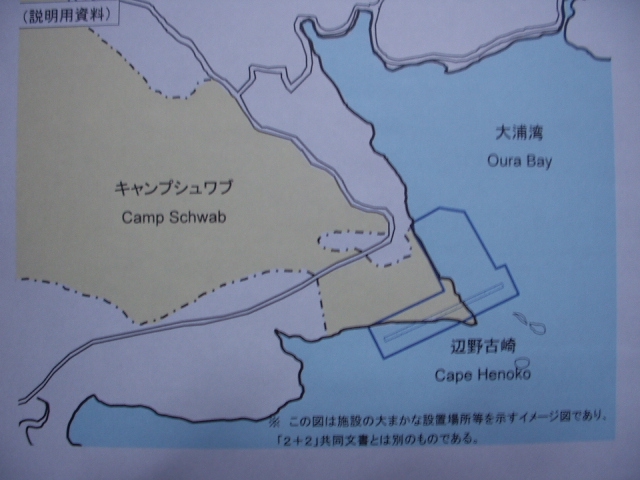

In 1997, however, the people of Nago City (the administrative unit that included the base site) intervened. In a historic referendum held under great political and financial pressure from Tokyo, the majority withheld consent from any base construction plan. Tokyo, refusing to consider any alternative, tried everything to break the city’s will: refusal of cooperation with the then prefectural Governor (who in 1998 decided to abide by the will of the Nago people rather than do the wishes of Tokyo), political arm-twisting, lavish handouts (bribery), and psychological warfare (a campaign to persuade Okinawans that their role in the defense of the rest of Japan should be something to be proud of). It achieved some success in cultivating an obedient, base-oriented mentality on the part of local government officials, and managed to sway the outcomes of a string of local elections, but the resistance remained strong. For much of 2004 and 2005 all attempts to conduct the necessary preliminary environmental survey of the base site (a few hundred meters from the current one) were defeated by a coalition of local and national environmental and anti-base groups, which camped around the clock at the site and surrounded and blocked the survey workers in canoes and small craft. In September 2005, Prime Minister Koizumi withdrew the plan. The new site was chosen in part because it would allow construction to be done from within an existing US base, Camp Schwab, a few hundred meters away from the one that Koizumi had abandoned. It consisted of a much expanded, dual runway, v-shaped structure that would span Cape Henoko and extend into the sea at both ends. Centering it on the base would make the site virtually inaccessible to protesters.

Nobody in Okinawa was consulted, and the decision sparked outrage across Okinawan society, from the Governor down. Surveys recorded unprecedented (85 per cent) levels of opposition to the project [4]. By sending in the SDF in May 2007 to help conduct the survey, Abe signaled his contempt for such Okinawan sentiment and his readiness to use force if necessary to deliver what the Pentagon (and Abe) wanted.

There was an especially bitter irony in the fact of the first dispatch of the forces of the newly (2006) upgraded Ministry of Defense against Okinawans. Okinawan understanding of “national defense” is forever marked by the experience of 1945, when tens of thousands died as the Imperial Japanese Army prolonged a futile resistance to the allied forces in the attempt to stave off as long as possible the attack on mainland Japan. Having been major victims then of Japanese militarism, Okinawans since then have had foisted on them the militarism that mainland “peace constitution” Japan on the whole avoided, first from 1945 to 1972 as a direct US military colony and then, from 1972, as administratively a part of Japan but one that was uniquely war-oriented and militarized.

By covertly deploying Japan’s military to Oura Bay, Abe was signaling a shift in the postwar state, something he is determined to consolidate by major constitutional revision, drastically diminishing local powers and extending the central authority of the state, giving priority to state over citizen, US over Japanese, military over civilian rights, and dismissing unheard the claims of the internationally protected species, including the dugong and the sea-turtles, that now thrive in the bay waters. When it came to a Japanese promise to the government of the United States, all stops would be pulled out to ensure compliance. While Prime Minister Hashimoto in 1998 promised that “the heliport [as the massive structure was then described] will not be build without local consent,” and Prime Minister Koizumi chose to abandon the project in 2005 rather than resort to force to implement it, Abe was not to be deterred. He would cross a line on Okinawa at which previous Japanese conservative administrations had stopped.

The SDF dispatch was thus unprecedented. The Japanese force whose sole constitutional justification was for the defense of Japan “against direct or indirect threat” was deployed instead to intimidate and impose the government’s will on a local community. The SDF dispatch was illegal (in breach of the purposes specified under the Self-Defense Law), and rode roughshod over Okinawan sentiment,[5] and was in breach of the constitution’s guarantees of local self-government autonomy. Even the conservative Okinawan Governor, Nakaima Hirokazu, whose candidacy in 2006 had been strongly supported by the governing Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and the national government, is on record as opposing the base construction plan (albeit “in its present form”) and spoke of the Bungo dispatch as “likely to stir in Okinawan minds memories of living under [American] bayonets.”[6] Military affairs critic, Maeda Tetsuo, remarked that if the SDF could be used on this occasion with impunity then they would be able henceforth to be used in any way the government of the day chose.[7]

The SDF dispatch also appeared to contravene the law relating to environmental impact assessment. The Cape Henoko/Oura Bay “preliminary survey” did not constitute the “Environmental Impact Study” required by law. It had no claim to be a serious or independent scientific survey since the government was firmly committed in advance and at the highest diplomatic level to delivery of this base to the Pentagon. Independent scientific opinion could therefore have no role to play, let alone local or international environmental groups. The company entrusted with the task well knew how important a positive evaluation was, and could be relied on not to disappoint or shock its employer; the outcome could not be in doubt.

For the US and Japanese governments, the attractiveness of this site stemmed from the assumption that local opposition could be bought off and/or crushed and from the physical proximity and therefore usefulness for the projection of force against North Korea and/or China. Neither paid serious attention to the dugong and turtles, or to the implications for the environment as a whole of building massive military installations in such a location. For both, this was a project already ten years delayed because of the stubborn opposition of Okinawan (and some mainland) citizens. This time, they reckoned, the deal would be implemented whatever the cost.

While the government thus defied the law, and treated Okinawans with contempt, the opposition movement continued, as it had done since 1996, to rely on democratic and legal means. Despite all the pressure, no opinion survey has ever found any majority accepting the Tokyo position. Despite the exhaustion of a decade of sustained struggle in defense of the constitutional principles of democracy and pacifism, the movement continues to come up with innovative strategies. One major action (still continuing) was launched in 2003 in a San Francisco court against the US Defense Secretary and Department of Defense seeking an order to halt the project on environmental grounds. In similar vein, a coalition of environmental groups in 2007 launched an international campaign calling for public hearings as part of a serious and transparent environmental impact assessment.[8]

The special measures law and the covert SDF action were necessary, in the view of the Abe government, because of the widespread opposition on the part of local governments and people, not only in Okinawa but also elsewhere to the military reorganization More than twenty local administrative authorities throughout Japan refuse to cooperate in the reorganization despite the blandishments and the pressures. The new law would multiply the pressures on such regions.

Nago City, the administrative district in which the new base site was included, was one such. When it opposed the decision of the two governments in 2005-6, it was told that in consequence the budgetary tax allocation for the city might be zero.[9] Tax allocations had hitherto been distributed on an impartial basis according to general principles and such sanction would, in effect, make local administration impossible; it would be tantamount to imposition of a blockade. Faced with that threat, and even before the new law came into operation, the Henoko District Administrative Committee withdrew its 1999 resolution against the “heliport” construction plan [10] and the Nago City authorities, by agreeing to the “preliminary” survey, were deemed to have given consent to the project within the terms of the law and thus to be entitled to the first installment of the designated subsidy.[11] Having thus tasted the fruits “of the subsidy for the obedient”, it would be more difficult in future for it to withhold cooperation.

As for Iwakuni City in Yamaguchi prefecture, when it was told that, under the “reorganization,” it had to host 59 carrier-borne US fighters to be transferred from the naval air facility in Atsugi, mayor Ihara Katsunosuke, following the Nago City 1997 precedent, in March 2006 conducted a plebiscite. He found a solid local majority (89 per cent of those voting, 51 per cent of eligible voters) saying “No”, and shortly afterwards was also returned to office. The national government’s response to the rebuff followed in December 2006 (i.e., even before the passage of the new law): it cut off funds promised for the building of new municipal offices [12]. As Ihara put it, the choice was: submit and gain 500 billion yen, or oppose and be plunged into bankruptcy.[13] In March 2007, the Iwakuni Assembly buckled to the pressure and passed a resolution asking him to take “practical and effective measures.”[14] Following the passage of the May law, Ihara’s position continues to erode under intense Tokyo pressure. Like Okinawa, Iwakuni is required to pay a heavy price to be made “beautiful.”

The situation is similar in Yokosuka (in Kanagawa prefecture). Reluctant “homeport” for 34 years to a US aircraft carrier, the mayor and assembly were shocked when told that under the “reorganization” from 2008 the existing carrier would be replaced by a nuclear one. Under heavy pressure, persuaded that defense matters had to be the exclusive preserve of the national government and local sentiment should play no part, the Yokosuka mayor agreed – despite a unanimous declaration of opposition by the municipal assembly. For their part, however, the mayors of the cities of Zama and Sagamihara (both also in Kanagawa prefecture), declared their determination to resist reorganization, in the case of the mayor of Zama even if a cruise missile was sent against him and in the case of the mayor of Sagamihara even if he was run over by a tank).[15]

Reliance on money and force under the May 2007 law was a recipe for dividing local communities, entrenching an opportunist and/or dependent mentality on the part of local officials, and reinforcing the priority of military over civilian, US over national priorities. As the Tokyo shimbun put it on 24 May, the threat of force was intended to deter local resistance. Such threats were only effective when accompanied by a readiness actually to use force. In that context, the dispatch of the Bungo was ominous.

Okinawan people have other reasons to be angry with the Abe government. It has been known for decades that the government of Japan lied about the agreement for the “reversion” of Okinawa to Japan in 1972, and that the “reversion” was really a “purchase,” the government of Japan paying the US substantially more, around 685 million dollars, for the “return” of facilities (which under the agreement actually remained under US control) than it had paid in 1965 to South Korea as compensation for four and half decades of Japanese colonialism, plus untold millions in subsequent subsidies.[16] It lied too by referring to the deal as one for Okinawa to be placed on a kaku-nuki hondo-nami (without nuclear weapons and on a par with the rest of Japan) basis when secret clauses of the agreement made clear that it would be neither. Despite the mounting evidence on this over recent decades, from US archival sources and from Japanese officials who played a central part in the process, the Japanese government sticks to its formal position of denial. Most recently, it was revealed that not only did the Japanese government pay the four million dollar component that was ear-marked to compensate local Okinawan landowners (which the US government was obliged by the agreement to pay), but that it put pressure on the US to delay the payment – evidently in fear the truth might out – with the result that only one quarter of the designated sum ever reached its supposed Okinawan beneficiaries.[17]

The Tokyo government’s stance on war and war memory is also especially sensitive to Okinawans. The Abe government is comprised almost entirely of those who deny Japan’s war responsibility and call for a “proud” version of Japanese history and a compulsory patriotism to be taught in the schools. Not only have they been successful in eliminating reference to comfort women from the nation’s school texts, but in the 2006 text screening process reference to the “compulsory suicide” of Okinawans was also deleted. No memory of the catastrophe of 1945 is more sacred to Okinawans than that of their forbears being ordered to kill themselves so as not to inconvenience the Imperial Japanese Army’s war.[18] Unsurprisingly, 81 per cent of Okinawans opposed this directive.[19] Since then, one after another, local governments across Okinawa have passed resolutions of protest and demands for the withdrawal of the order.[20]

Okinawa reveals in concentrated form the contours of the Abe state that are less visible from Tokyo or Osaka. The Abe project, including proving loyalty to Washington, depends on purging Okinawans of their pacifism and overcoming their commitment to preservation of their environment and co-existence with endangered species; ultimately, it may even require purging their war memories too.

Okinawan bitterness at the Abe government continues to build. Okinawan elites may be swayed by promises of subsidies or deterred by threats, but the Abe sense of beauty is widely seen as a bizarre 21st century attempt to return to the fantasies of the emperor-worshiping militaristic past. Most Okinawans watch in fascinated horror as the Abe government’s calls for beauty contrast ever more starkly with the reality of its sinking into a morass of corruption scandals and bizarre statements (women as baby-producing machines, human rights as a non-Japanese ideology best kept within limits, and “Comfort Women” as volunteer prostitutes providing the wartime Japanese forces a service akin to present-day university cafeterias). They are not inclined to see much beauty in this or in the reorganization of Japan to serve US security concerns. They sense that they are prime targets for the May reorganization law.

Furthermore, they understand that the economic benefits of obedience to Tokyo and dependence in the past have been more illusory than real, and expect little change under the “incentive” system of the new law. Tellingly, those contending for office in Okinawa have never presented themselves as proponents of militarization. Instead, both the previous and the present Governors, Inamine Keiichi elected in 1998 and Nakaima Hirokazu elected in 2006, adopted a pose of studied ambiguity on the bases while campaigning instead on their promise to use their superior national government connections to lift Okinawa out of poverty. Yet the poverty remains, Okinawa’s economy remains stubbornly flat – joblessness at about double the national average and per capita income half that of Tokyo. Abe’s “beautiful country” policies enforce a dependence that prolongs and deepens it.

Notes

[1] For details, Gavan McCormack, Client State: Japan in the American Embrace, New York and London, Verso, 2007, chapter 4 (published June 2007).

[2] For a short account: “Diet passes ‘incentive’ bill to realign US forces,” Asahi shimbun, 24 May 2007; Editorial: US military alignment,” Asahi shimbun, 25 May 2007.

[3] The following account draws from chapter 7 of Client State.

[4] Details in Client State.

[5] Protest statement by representative Okinawan intellectuals and public figures to Prime Minister Abe and Defense Minister Kyuma, 24 May 2007, courtesy Sato Manabu of Okinawa International University. See reports in Okinawa Times and Ryukyu shimpo, 25 August 2007.

[6] “Beigun saihenho – kane to atsuryoku dake de wa,” Tokyo shimbun, 24 May 2007.

[7] Nishi Nihon shimbun, 19 May 2007.

[8] Launched in May 2007 by Save the Dugong Campaign Center and Citizens Assessment Nago, with support of WWF (World Wildlife Fund)-Japan, Nature Conservation Society of Japan, Save the Dugong Foundation, and the “Ten Districts Association” of Eastern Nago. (Information from Hideki Yoshikawa, Nago City. For an earlier analysis, see Yoshikawa’s January 2007 Japan Focus essay “Internationalizing the Okinawan struggle.”)

[9] “Beigun saihenho seiritsu – chiiki no jiritsushin mushibamu,” editorial, Okinawa Times, 24 May 2007.

[10] “Hantai ketsugi o bankai– Henoko ku hyosei-i ‘kensetsu nara yobo jitsugen o,” Ryukyu shimpo, 16 May 2007.

[11] “Nago-shi wa ukire bun – saihen kofukin,” Okinawa Times, 25 May 2007.

[12] Voters might have assumed, when voting in the March 2006 plebiscite, that they would not get any future, defense-related subsidies; that was their choice. But probably none suspected that Tokyo would go so far as to renege on an existing commitment, unrelated to base issues but stemming from the huge expansion in the size of the city under an administrative reorganization.

[13] Quoted in Imai Hajime, “Abe seiken ga Iwakuni shimin ni kaeshita ‘utsukushii kotae’,” Shukan Kinyobi, 23 March 2007, pp. 56-58.

[14]Realignment of US forces should be sped up,” Yomiuri shimbun, 24 May 2007.

[15] “Hondo no Beigun saihen,” Asahi shimbun, 19-22 February 2007.

[16] The official figure is 320 million, but Gabe Masaaki of the University of the Ryukyus concludes from his painstaking research that the real figure was 685 million. See my discussion in Client State, p. 158.

[17] Kyodo, “Sordid details of Okinawan reversion deal revealed – Japan asked US to delay compensation for landowners,” Japan Times, 16 May 2007, posted on Japan Focus, 17 May 2007.

[18] For a recent assessment of the evidence on this tragic story, “Shudan jiketsu ‘gun kyosei’ o shusei,” Asahi shimbun, 31 March 2007 (and other articles in same issue of Asahi). In the worst cases, on and around the Kerama Islands in late March 1945, close to 500 people are thought to have died. Detailed testimony is detailed in the official histories of Okinawa prefecture and of Tokashiki village (on Kerama).

[19] “Monkasho no Okinawa ‘shudan jiketsu’ gun kanyo massho o yurusanai,” Shukan Kinyobi, 20 April 2007. Also “Kataritsugareta Okinawa-sen,” Okinawa Times, 13 May 2007.

[20] Okinawa Times, 29 May 2007.

Gavan McCormack is an emeritus professor of Australian National University, a coordinator of Japan Focus, and author of the just published Client State: Japan in the American Embrace (New York and London: Verso). He wrote this article for Japan Focus. Posted May 30, 2007.