Abstract

Gavan McCormack here explores matters raised in his 2018 book with Satoko Oka Norimatsu (Resistant Islands: Okinawa Confronts Japan and the United States, 2nd edition), outlines recent judicial, political, diplomatic and ecological developments with a bearing on the “Okinawa problem,” and considers the tactics and strategy employed in the long-running contest by Okinawa’s social movements on the one hand and the Japanese and American states on the other. The text that follows is a slightly revised version of the invited lecture he delivered at International Christian University in Tokyo on 11 November 2019.

Okinawa – The Prefecture That Keeps Saying No

Modern Japanese history has no precedent for the phenomenon of a prefecture saying “No” to the authorities of two of the world’s great powers, and doing so consistently, over a period of decades. The political history of Okinawa in the 47 years since its reversion has been one of resistance to the assigned status of Client State of the United States’ Client State of Japan. Prime Minister Abe appears to see Okinawa as a patch of enemy territory within an otherwise submissive domain, yet it is the Okinawans who take seriously his call for going “beyond the post-war system” and “taking back” Japan. For them, however, it is Okinawa itself, “lost” 74 years ago, that is to be taken back and Abe who stands in the way, blocking them.

Okinawa’s confrontation with the Japanese nation state is rooted in the unique experience of incorporation by violence – into the early modern (Edo) state in 1609 and into the modern (Meiji) state in 1879,1 followed by the overwhelming catastrophe of war in 1945, the ensuing severance from Japan, US occupation between 1945 and 1972 as Japan’s “war state,” matching the mainland-Japan “peace state” under the San Francisco Treaty determination of 1951,2 and the fierce, ongoing confrontation with the national government over the key national policy for Okinawa from 1972: that its raison d’être has to be: serve the United States.3

During the early years of US occupation, while under complete US military control, the islands were assigned a key role in global war planning. Up to 1,300 nuclear weapons were stored there and Pentagon planners assumed a major role for Okinawa in scenarios involving the destruction of all major cities in the then Soviet Union and China, with the killing of around 600 million people (sic) very possibly bringing human civilization itself to an end.4 Okinawans, struggling then against the appropriation of their land, believed that if only Okinawa were to be restored to Japan the principles of the constitution would ensure recognition of their democratic rights and the winding back or return of their land. It was a vain hope. Instead, under the process known in Okinawa as the terror of “bayonet and bulldozer” expropriation of their land proceeded inexorably, and military bases were consolidated. After the reversion (in 1972), US hegemony, and the associated priority to its military, simply became entrenched.

With the end of the Cold War, Okinawans again began to hope for a “peace dividend” via the return of their land. Not only was this not to be, but the infamous rape of a twelve-year old Okinawan girl by three US servicemen in 1995 stirred unprecedented anger and sadness. The two governments sought to quell these sentiments by promising that Futenma Marine Air Station would be returned within “five to seven years.” Like the “reversion” of Okinawa itself in 1972, it was an empty promise. Futenma would only be returned once a substitute facility had been constructed, and that substitute would have to be in Okinawa. The proposal was rejected, firstly by a Nago City plebiscite in 1997, by numerous resolutions of the Okinawan parliament and successive Okinawan governors, but the Japanese and US governments have not since wavered.5 The project, initially for a “heliport,” gradually grew into a grand, multi-functional facility with twin, “V”-shaped, 1,800-meter runways on a platform projecting ten meters above the sea, plus ancillary deep-sea port and storage facilities.

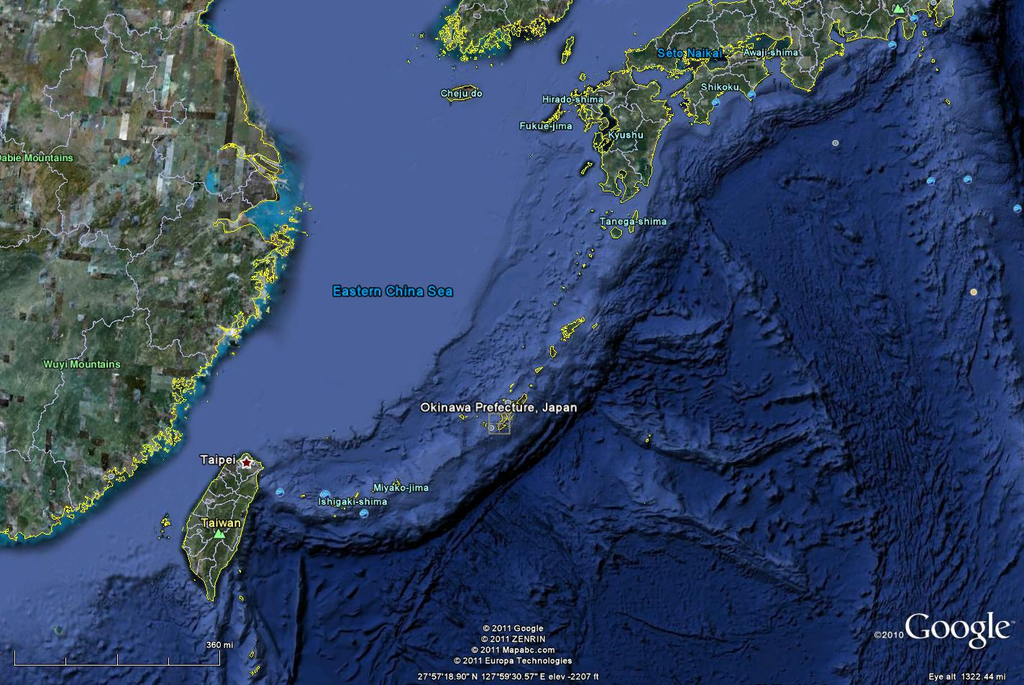

|

Okinawa and Its Surrounds |

Confrontation, Judicial and Political, 2006-2019

Following the agreement of the two governments on the grand design for “Realignment of US Forces in Japan” (2006), and preliminary survey works at the designated site, Henoko on Oura Bay, the issue moved to the top of the agenda of Okinawan politics.

A governor committed to stopping the proposal, Nakaima Hirokazu, was elected in 2010. Under heavy pressure – or just possibly in accord wth a carefully orchestrated plan – he reversed himself three years later, agreeing to the reclamation of Oura Bay and the construction of the new base. He was denounced by the Prefectural Assembly, then voted out of office the following year (2014), replaced by Onaga Takeshi, elected on a mandate to continue the opposition to the base. Onaga did indeed stop the works in October 2015, cancelling (torikeshi) the license, but his order was immediately countermanded by the Japanese government and the Supreme Court ruled against him in September 2016.6 Preliminary construction work resumed in April 2017, continuing through 2018. In July 2018, confronting serious, soon to prove fatal, llness, Governor Onaga launched formal proceedings to rescind (tekkai) the original, problematic reclamation license issued by his predecessor. But no sooner did he do this than he died (on 8 August).

The prefecture continued the process of revocation, and works were suspended (from 31 August). Again, however, the state moved to strike down the prefecture’s protest. The (government’s) Okinawan Defence Bureau called on Ishii Kei-ichi, Minister of Land, Infrastructure, and Transportation, to review the prefectural revocation under the Administrative Appeal Act and issue an order cancelling its effect. On 30 October, Minister Ishii did what was required of him, suspending the prefectural order and ruling that any rescission of the reclamation permit was “unreasonable” and “likely to undermine relations of trust with Japan’s security ally, the United States.”7

In September 2018, despite an unprecedented level of national government intervention on behalf of its preferred Liberal Democratic Party candidate, the anti-base construction Tamaki Denny was elected governor by a massive (eighty-thousand-vote) margin. His campaign pledge was clear: he would stop the Henoko reclamation/construction works. Within days of his election, however, the Abe government declared that it intended to proceed regardless of prefectural sentiment. Brushing aside outraged Okinawan protests, the Okinawa Defense Bureau (ODB) ordered works at Oura Bay to be resumed. This happened in November, just over a year ago. Since then fleets of tankers and ships have been mobilized, but to date works have been confined to the shallow waters of the Henoko side that constitute around one-quarter of the reclamation site, leaving untouched the deep waters of Oura Bay. Through 2019, works continued but they amounted to a tiny fraction of the overall project.8

As successive recent Okinawan prefectural and national elections returned anti-base construction candidates, Governor Tamaki has repeatedly called on Prime Minister Abe to enter a dialogue on the differences between nation and prefecture, but Abe refuses. The national daily Asahi editorialized early in 2019 that the Henoko project was “clearly doomed” and that it was time to “to open talks with the US.”9 The civic opposition protest movement continues on a day-to-day basis while the Government spends a staggering 20 million yen (around $180,000) per day, just for security guards whose job is to crush or inhibit local opposition.10 In 2016-2017 the UN Human Rights Commission lambasted the government of Japan for its five month-long detention of protest leader Yamashiro Hiroji in solitary confinement as if he were a terrorist.11 Yamashiro had baffled and infuriated the state by his brilliance as choreographer of the resistance, leading it in song, dance and debate. He was therefore a dangerous foe. His confinement, the UNCHR said, “constitutes a violation of Articles 2 and 7 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and Articles 2 (1), 26 and 27 of the Covenant, on the grounds of discrimination against a civic activist aimed at and resulting in ignoring the equality of human beings …”

Expert opinion on the Henoko project is negative. To cite just three examples: in October 2018 a statement bearing the signatures of 110 administrative law specialists declared the government to be acting “illegally … lacking in impartiality or fairness,” and failing “to qualify as a state ruled by law;” 12 in January 2019, 131 constitutional law specialists, academics and lawyers, published a similar statement declaring the government’s actions a matter of the fundamental human rights of the people of Okinawa, and the Henoko project both illegal and unconstitutional.13 Finally, in a prefectural referendum on 24 February 2019 just over 72 per cent of voters said No to the project, far outweighing the 19 per cent in favor of it (or the 8.7 per cent who voted “neither”).14 Undeterred, the government pressed ahead.

Although Prime Minister Abe insists that Japan is a country governed by law, as one representative of this constitutionalist group put it, “What the Abe administration is doing in Okinawa is, precisely, trampling on the ‘rule of law’.” Governor Onaga (in office 2014-2018) was acclaimed by Okinawans when he berated the national government as “condescending,” “outrageous,” “childish,” “depraved,” [rifujin, otonagenai, daraku shita] and “ignoring the people’s will.”15

Prospects, 2020 and Beyond

All attempts by the two governments over a period of decades to persuade, buy off, or intimidate the people of the Okinawa islands into submission to the clientelist, military-first prescription have failed. Works continue, and such is the imbalance of forces that one would have to think the Okinawan resistance doomed in the end to be crushed and Okinawa subjected permanently to military priorities. What are the prospects in this mighty struggle between the governor and people of Okinawa and the state of Japan?

Firstly, it is almost inconceivable that Okinawa prefecture might win a judicial victory, a court at some level finding for them and ordering a stop to the Henoko base works. Ever since the Sunagawa case in 1959 the principle adopted then by the Supreme Court has held firm: that matters pertaining to the security treaty with the US are “highly political” and so not to be subjected to judicial contest.16 In effect, the Security Treaty (Ampo) trumps the constitution (Kempo). There is no division of powers, and the judiciary is sure to uphold state prerogative. Even if every single Okinawan were to say “No,” the government would still press ahead and the courts would legitimise its doing so. The new base would be built.

In February 2019, a panel for the resolution of disputes between central and local governments rejected an Okinawan prefectural government plea to overturn the Ishii order on technical grounds.17 It was the fifth negative or unresponsive judicial ruling, and the prefecture months later launched two suits – the sixth and seventh in the Henoko judicial saga – challenging the validity of National Land Minister Ishii’s cancelation of the Okinawa Governor’s August 2018 cancelation of the reclamation license, one under the Local Autonomy Law in the Naha branch of the Fukuoka High Court on 18 July and the other under the Administrative Case Litigation Law in the Naha District Court on 7 August.18 It protested both formally that the Minister’s decision had been an improper exercise of power by the government – acting as both “player and umpire”19 as Denny put it – since one section of it was adjudicating on the propriety of the act of another, and substantively, that the site was incompatible with the military purposes assigned it because the Bay floor was composed of sludge and there were active fault lines across it. For this it cited evidence obtained from the government under Freedom of Information.

From 2018 two significant new factors became apparent: “Bay-Bottom Mayonnaise” (as it came to be known) and active fault lines. These two factors shook the reclamation project. Concealed from the public at the time of the environmental impact survey (2014-2016), both only came to light in 2018 due to the efforts of civic protest groups. Structural engineers now doubt that the massive concrete and steel structure that has been planned for Henoko-Oura Bay could be stably imposed on the designated site because of those two factors. At very least, the original design would have to be fundamentally redrawn, and that would be impossible without prefectural consent.20 In December 2018, the government said that it wanted to address the problem by inserting forty thousand sand compaction piles into the seabed. In January, it raised the number to sixty thousand. A few weeks later it became 76,999, while increasing the depth to which they would have to be inserted from sixty to ninety meters (sixty in water and thirty in sludge).21 On 30 January 2019 Prime Minister Abe made a remarkable admission to the Diet: he could neither say when the project would be completed nor how much it would cost.22 Two weeks later, on 15 February, his government submitted to the Diet documents reckoning that “bottom enforcement” works would take an additional three years and eight months, so that, even according to the “best” scenarios for construction, the date for reversion of “the most dangerous base in the world” Futenma would be pushed well back from the current estimate of 2022. Okinawa prefecture estimates, however, that it could take at least thirteen years, and – if indeed it could be carried out at all – would cost around two and a half trillion yen ($23 billion), or ten times the original estimate.23 Independent experts reckon that the sand pile works, if indeed they were possible, would take till around 2025. They would then have to be followed by construction of sea-walls and the actual “fill,” and only then could the base facilities be constructed. The whole process would likely take no less than 20 years.

It is seriously to be doubted whether Japan has the engineering skills or experience for reclamation under such conditions, but, even if the government persists with the project, [determined to save face with Washington] it would call for “more than 90” sand compaction vessels to be mobilized to Oura Bay, anchor chains scraping the sea-bed, with 3 million 10 ton truckloads of fill to be dumped into the Bay then, bringing noise and pollution certain to weigh heavily on dugongs, sea turtles, and other denizens of the Bay.24

Apart from the mayonnaise bay bottom and the fault lines across Oura Bay the time for building military bases on sea-front sites may have passed due to the threat of rising ocean levels caused by global warming.25 As the collapse of the polar and Himalayan glaciers gathers momentum, ocean front cities such as Naha and Nago are bound to suffer. It is a factor not yet seriously considered, but undoubtedly the Pentagon has an eye on it. According to one well-informed observer, the major US naval shipyard at Norfolk, Virginia, might become unusable thirty years from now, and that same fate likely awaits the projected Henoko base “in 60 or 70 years.” 26 Kansai International Airport (opened in 1994) was also built on a reclaimed island (in Osaka Bay) at a cost of around $20 billion, but, although also reinforced by the insertion of multiple piles, it continues to slowly sink and had to be closed when almost submerged by storms in 2018.

To sum this up, as of late 2019 the government is insisting that it will dig 77,000 holes deep into the Bay floor, insert a ninety-metre-high pillar of sand into each one, and top it with a vast spread of concrete and steel, using untried engineering techniques, in an unpredictable time frame and at uncertain cost, without seriously affecting the bay as eco-system for the thousands of creatures that live there. Nobody now thinks any Futenma reversion could occur before 2025, and many predict it might take until the late 2030s. Were it located in the continental US in such a high-risk setting, such a project would never get off the ground and, irrespective of any replacement Futenma Marine Air Station would be closed forthwith, without substitution, for safety and environmental reasons.

On 23 October 2019 the court delivered its verdict in the first of the two 2019 cases. It brusquely dismissed the prefecture’s case. On the procedural matter, it found, mysteriously, that although there were differences between a claim by an individual and a claim by the state, “in matters of substance (honshitsu bubun) there was no difference,”27 in effect declaring that state power was not to be constrained by the constitutional principle of local self-government. The Asahi shimbun summed up the outcome by saying

“It is utterly unacceptable for the courts, which are supposed to see that the law is observed, to retrospectively legitimize governmental acts that trample on the spirit of the law.”28

The court had nothing to say on the substantial question of the highly problematic site.

While judgement in this (July 2019) case is referred on appeal to the Supreme Court, proceedings still continue in the second (Naha District Court) case in which the prefecture has filed a 432-page document with several additional attachments.29 If the courts are true to form, judgement in a few lines retrospectively endorsing decisions by the national government can be expected.

Political Resolution?

If the judicial prospect (the one within Japan at least) looks uncertain, what then of the prospect of a political resolution? Might the popular movement evolve to such a point that it can compel the government to back down and submit to the will of the Okinawan people? That seems unlikely. Prime Minister Abe is most likely impervious to any essentially moral case. The sit-ins and protest events to date have certainly delayed, complicated and raised the costs of the works, but they have not stopped or even seriously threatened them. Currently the Tamaki administration is attempting to sway national (and international) opinion by a “caravan” campaign pleading the “All-Okinawa” cause nationally and by presentations by the Governor and members of the Prefectural Assembly internationally, but again to date without significant (or at least conspicuous) impact. Fresh tactics might be envisaged, such as a theoretically imaginable general strike or a cut-off of supply of local labour or electrical power to the bases, or perhaps, as some have suggested, a mass floating of balloons across the flight paths of US military aircraft, but the Okinawan movement sticks to classic, non-violent appeals to law, reason, and persuasion, believing that truth and justice will eventually prevail. It faces, however, a ruthless and unprincipled opponent, and the odds against any “local” movement pitted against the nation state are almost infinitely unequal.

There are some common misconceptions about the balance of forces in the contest for Okinawa. While it is the case that the Governor and majority Okinawan opinion is clear in its opposition of new base construction at Henoko, it is also the case that pro-base (or base-tolerant) forces have gained ground in political circles throughout the islands, under relentless state pressure. While “All-Okinawa” candidates have won 12 and lost only one of the gubernatorial and national Diet elections over the five years from 2014, at the city mayor level eight of the prefecture’s eleven local government bodies, including key centres such as Ginowan, Nago, and Okinawa cities, are now headed by mayors who belong to “Team Okinawa” who are for the most part silent on the Futenma replacement and Henoko construction issues but are backed by the Liberal Democratic Party and cooperate with the Abe government. They constitute a well-organized and strongly Tokyo-backed opposition to the anti-base “All-Okinawa” forces led by Governor Tamaki.”30 In September 2019, when Ginowan City Assembly, reluctant home to Futenma Marine Corps base, adopted a resolution calling for the Futenma base to be relocated from within its city boundaries to Henoko (in Nago City), it was the first time that any local government body declared explicit support for the government’s relocation agenda.31 It followed, and in a sense responded to, the resolution adopted the previous day by Nago City Assembly demanding an immediate halt to construction works at Henoko. Having waited 23 years (since 1996) for the return of core city lands long appropriated by the US Marine Corps, it is not surprising that some in Ginowan City political and economic circles should surrender to the government’s plan to accomplish reversion by shifting the burden to another city. Upon such divisions the Government is bound to work harder henceforth to drive the wedge deeper and to persuade other cities to submit.

It may be that the “Okinawa” cause can only be effective nationally when “All-Okinawa” becomes “All-Japan,” when the struggle comes to be and to be seen as “national,” when regular charter flights begin to ferry mainland students, citizen activists, professors to join the Bay-front protests, and when the Okinawan case is effectively presented before multiple international fora.

All-Okinawa’s Slightly Ambiguous Leadership

In terms of the balance, or imbalance, of forces, the Governor is a somewhat ambiguous figure. The common view beyond Okinawa is that both the present and immediate past Governors (Tamaki Denny and Onaga Takeshi) are/were anti-base and anti-military, but that is not quite true. Both have been conservative supporters of the base system and the US-Japan military alliance, for that reason unlikely to confront the nation state in any radical way. In fact, with the sole exception of Ota Masahide, governor between 1990 and 1998, no Okinawan governor has challenged the overarching insistence of the US and Japanese governments that military and alliance interests should be paramount in determining Okinawan policy. Former Governor Onaga even seems to have entertained the bizarre aspiration to have Okinawa serve as a global command center for the Marine Corps.32

It is also the case that, like Onaga before him, Governor Tamaki today confines his objections to the Henoko new base project. He takes no position on the comprehensive militarization of the prefecture, on the helipad works in the Yambaru forest in the north of Okinawa Island or on the Abe government’s rapidly advancing plans for the extension of military (i.e., Japanese Self-Defence Force) facilities through the Southwest islands adjacent to Okinawa island, notably Miyako, Ishigaki, and Yonaguni. Tamaki confirmed his pro-Security Treaty, pro-base stance in speeches in Tokyo and New York in November 2018.33 He makes no real effort to ban the use of northern Okinawan ports for transport of reclamation/construction materials by ship, (and of fill by road) and very recently he introduced his and the prefecture’s stance in a May 2019 letter to the US ambassador (and through him to President Trump) that adopted an almost grovelling tone, saying that he, and Okinawa, “appreciate the United States government for its tremendous contributions in maintaining the security of Japan as well as the peace and security of East Asia.”34

Tamaki also supports the “return” by the US of Naha Military Port. That return, first promised in 1974, 45-years ago, was made dependent on construction of an alternative. As “reversion” of Futenma Marine Air Station meant construction of the much expanded and upgraded Henoko facility, so that of Naha Military Port came to mean major new base construction at adjacent Urasoe. In 2019, long suspended negotiations on the move were resumed between the prefecture, Naha City and Urasoe City,35 none expressing any doubt as to the prefecture’s continuing to host a major US military port facility. The Naha Military Port, like the Kadena US Air Force base and the Marine Corps’ Futenma, is sacrosanct. “Reversion,” for any major US military facility, can only be upgrading or improving. For daring to suggest otherwise, and conceiving of a future demilitarised Okinawa, Ota earned the unrelenting hostility of Tokyo and was removed from office.36 The return of Naha Military Port, already 45-years delayed, could not occur earlier than 2028.37

Furthermore, Governor Tamaki was no sooner elected than he indicated his readiness to consider one of the key US demands for the Japanese client state: the transformation of military bases in Okinawa from single (US or Japan) management and use to “joint” facilities.38 His declaration to the right-wing national newspaper Sankei Shimbun occurred almost simultaneously with the report of the Washington Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) making precisely that demand. Both were looking to reinforce the US-Japan alliance.39 So the Okinawan Governor’s message to Tokyo and Washington is to support and embrace Ampo; just please stop Henoko.

Within the anti-base Okinawan movement it may be necessary to widen the focus of struggle from the effort to stop Henoko to combat the deeply entrenched, comprehensive prefectural submission to the US military (including but not confined to Henoko), the ongoing expansion of Japan’s own militarism on the outlying Okinawa islands and the planned development of the new Urasoe “Military Port” base project.

Okinawa in (US) Court and Congress

But if the domestic prospect does not look very bright, what might be the prospects beyond Japan? The internationalisation of the Okinawa issue is a hugely complicating but also potentially hopeful angle. Global attention occasionally focuses on Okinawa, as in January 2014 when 103 “international scholars, peace activists and artists” issued a statement condemning the moves to reclaim a swathe of Oura Bay and construct the base.40 But it proved difficult to maintain that momentum and the matter became so complex that many grasp its twists and turns. The more complex the issues, the less journalists strive to follow and report them; they desire drama, a simple message.

However, there is a possibility of a thumbs down from either a US court or even directly from the Pentagon on the Henoko project. Two such matters warrant attention. First, a suit launched in 2003 in the name of the dugong [that docile, seagrass-munching mammal] by a coalition of Okinawan, Japanese and American nature NGOs in a Californian district court under the US National Historic Preservation Act (1966) is currently before the US Court of Appeals with a verdict expected in 2020. It has become one of the longest-running nature protection suits in US history. The court is considering a US/Japan NGO appeal in the name of the dugong, in the case that began as “Dugong vs Donald Rumsfeld” against a Californian court’s August 2018 ruling in favour of the government’s construction plans. The NGOs insist that the government’s withholding of crucial environmental information (especially the sea-bottom mayonnaise) should make its conclusion that the endangered adugong would not suffer “adverse effects” from construction improper and unwarranted.41

|

Illustration from the “Save the Dugong” International Campaign |

It would be hard to imagine a more serious and adverse effect of the project for the dugong than extinction. Little attention has so far been paid to this ongoing case in either Japan or the US, but its implications are considerable. It amounts to a major test of the independence of the US judicial system. It is very much a confrontation of our times between nature and militarism, and it may well be that the chances are better of a favourable judicial outcome in a US court than in a Japanese one.

There is also a significant new development on the US political front. The US Congress is currently undertaking a “review of the planned distribution of members of the United States Armed Forces in Okinawa, Guam, Hawaii, Australia, and elsewhere” under the National Defense Authorization Act. Seizing that as an opportunity, thirty-three Okinawan civil society organizations recently addressed a cogent appeal to the Senate and House Armed Services Committees, calling for reconsideration of the Henoko project as part of this process on “democratic, legal, environmental and cultural” grounds.42 In November 2019, Governor Tamaki appealed to US government circles in Washington on this matter. The outcome is far from assured, but while the United States has from time to time indicated an openness to consider alternatives to Henoko, insisting that it is a matter for the Japanese to resolve, so long as the Japanese government remains adamant and pays for everything, it seems likely that the US government will continue showing the green light even if it agrees with the analysis posed by Okinawan civil society, and actually thinks of it as a dubious, if not already failed, project.

Still, the fact is that “Okinawa” was included in the original Senate draft as needing to be reviewed. If indeed it is reviewed, the absurdity of the project will be difficult to conceal.

UN(ESCO) and IUCN

The Government of Japan in 2017 submitted an application for registration of a swathe of territory in the Okinawan Islands (Amamioshima, Tokunoshima, Iriomote and the Yambaru forest of northern Okinawa) as World Heritage wilderness. The question of Yambaru, adjacent to the US military’s Northern Training Area and close to the Henoko-Oura Bay base construction site, raises acute problems for a government that has repeatedly made clear that base and military considerations trump climate change or species depletion in determining policy.

As part of the deliberative process, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), which advises UNESCO has already called three times (2000, 2004, 2008) on the Japanese and US governments to “conduct a proper EIA and to implement a protection plan for the dugong.”43 Addressing the Government of Japan’s 2017 submission it raised significant questions and called on Japan to “clarify” its “Northern Parts of Okinawa Island (NPOI)” [i.e. the Yambaru forest] submission. The government of Japan thereupon withdrew its submission, revising and re-submitting it early in 2019,44 but still failing to mention the fact that parts of the proposed Wilderness had been used for decades as a US jungle warfare training site and remained “littered with bullet shells, unexploded ordnance, and other, discarded military materials, including toxic chemicals.” It likewise failed to note that the Henoko Marine Corps base which the Government is intent on constructing would, if ever completed, house at least 70 military aircraft that would among other things conduct low-level and night flights above the forest. Even as the government struggled to find a verbal formula that would not dwell on such matters that might diminish the prospects for approval of its Heritage project, the precious environment of Yambaru forest and Oura Bay degenerated. Apart from the coral, by 2019 the dugong was thought probably extinct,45 and the Okinawa woodpecker (noguchigera) endangered.46

It strained global credibility for the government of Japan to declare that Northern Okinawa will be both protected as one of the world’s most bio-diverse and pristine environments and simultaneously developed into a world-ranking concentration of military force.

Japan marked the year 2018, the International Year of Coral, by setting about reclaiming much of one of the world’s most bio-diverse coastal coral reef zones, killing off unique and precious coral colonies and multiple other marine species in the process. Prime Minister Abe assured the Diet that endangered coral from the construction site had been safely transplanted when in fact just nine Porites Okinawensis colonies had been relocated, of a total of 74,000 needing transplant.47 Prefectural permission (unlikely to be granted) is required and the survival rate for transferred coral is very low. For Okinawa, in other words, the national polity of Japan as a US client state calls for transformation of one of nature’s greatest natural treasure-houses into a fortress from which the United States could continue indefinitely projecting its power over East Asia. It was, “counter to the moves towards regional peace, cooperation and community, counter to the principle of regional self-government spelled out in the constitution, counter to the principles of democracy and counter to the imperative of environmental conservation.”48

Conclusion

As the problems mount, more experts, and more peace, human rights, and environmental organizations are likely to come to doubt the Government of Japan’s competence and the viability of its scheme, and to see it, as did the editorial board of the New York Times in October 2018, as “an unfair, unwanted and often dangerous burden on Japan’s poorest citizens.”49

For Okinawans, the continued depredations on their environment in the name of defense and national security have the same ring as would the appropriation of the Grand Canyon as a military base to a citizen of the United States. In sum, the Okinawan anti-base movement has judicial, political, and environmental levers of pressure to try to secure its objectives against the national government. Their coordination across Okinawan, national, and international fronts is the challenge. The essential absurdity of the Henoko project is their core message. While the prospect of a favorable outcome at the political or judicial level in Japan is far from bright, it is somewhat brighter in the US court system, the US Congress, and the UN-centered global environmental protection forum (UNESCO/Wilderness/IUCN). Were any such to occur, it would have huge potential consequences.

Otherwise, there is the potential for the intervention of nature itself. Abe’s government likely have no real technical “fix” for the project’s immense geological, seismological, and climatological problems. Human laws may be twisted or ignored, but not so the laws of nature. While the two governments ride roughshod over Okinawan creatures such as the dugong, the woodpecker, and the blue (and other) coral, it is at least possible that Okinawan nature might launch a successful resistance in the unlikely venue of a US court.

Fatigued by decades of exhausting struggle against a relentless and unprincipled foe, the sentiment nevertheless remains strong in Okinawa that the “immovable object” of popular resistance will prove more than a match for the “irresistible” force of the Japanese state, that therefore Henoko will not be built, and that a halt can be called to the steady militarisation of Okinawa and its adjacent islands.

|

Resistant Islands, Second Edition, Rowman and Littlefield, 2018. |

Notes

See my “Ryukyu/Okinawa’s trajectory: from periphery to centre, 1600-2015,” in Sven Saaler and Christopher W.A. Szpilman, eds., Routledge Handbook of Modern Japanese History, London and New York: Routledge, 2018, pp. 118-134.

See my “The San Francisco Treaty at Sixty—The Okinawa Angle,” in Kimie Hara, ed, The San Francisco System and Its Legacies: Continuation, Transformation, and Historical Reconciliation in the Asia-Pacific, New York and London, Routledge, 2014, pp. 144-161.

For details, Gavan McCormack and Satoko Oka Norimatsu, Resistant Islands: Okinawa Confronts Japan and the United States, Second Edition, Rowman and Littlefield, 2018.

Daniel Ellsberg, The Doomsday Machine: Confessions of a nuclear war planner, London, Bloomsbury Publications, 2017, and Ellsberg in conversation with Peter Hannam, “Setting the world alight,” Sydney Morning Herald, 9 March 2018.

For details, McCormack, The State of the Japanese State: Contested Identity, Direction, and Role, Folkstone, Kent, Renaissance Books, 2018 and McCormack and Norimatsu, Resistant Islands, 2018, passim.

Kyodo, “Okinawa governor meets top gov’t official over US base transfer,” The Mainichi, 6 November 2018.

As of late 2019, Okinawa prefectural government estimated a completion rate of three per cent. One independent expert thought the true figure would be less than one-per cent.

The per person daily rate is a remarkable 90,000 yen or around $825. (Mochizuki Isoko and others, “Zei o ou – hadome naki boeihi (10) Henoko-shin kichi kensetsu kenmin osae saigen naki yosan,” Tokyo shimbun, 25 November 2019).

McCormack and Norimatsu, Resistant Islands, 2018, pp. 295-6. And see, Working Group on Arbitrary Detention, Human Rights Council, “Opinion No 55/2018 concerning Yamashiro Hiroji (Japan),” Opinions adopted by the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention at its eighty-second session, 20-24 August 2018,” UN Human Rights Council, 27 December 2018 A/HRC/WGAD/2018/55

“Henoko shin kichi, gyoseiho kenkyusha 110 nin no seimeibun zenbun,” Okinawa taimusu, 31 October 2018.

“131 constitutional scholars speak up against Henoko base construction,” Ryukyu shimpo, 24 January 2019. (Words quoted from Iijima Shigeaki of Nagoya Gakuin University).

Eric Johnston, “More than 70% in Okinawa vote no to relocation of US Futenma base to Henoko,” Japan Times, 24 February 2019.

On the grounds that the prefecture’s suit was based on the Administrative Complaints Review Act, but that the tribunal only had jurisdiction over complaints under the Local Autonomy Act (“Dispute resolution panel throws out Okinawa request to reinstate landfill ban,” The Mainichi, 19 February 2019).

For a summary of these two suits see Okinawa Environmental Justice Project, “Review Henoko Plan!: 33 civic groups send a statement regarding US National Defense Authorization Act for FY 2020,” 1 November 2019.

“Nanjaku jiban ni kui 6 man bon, koto mukei na koji o yameyo,” editorial, Ryukyu shimpo, 3 February 2019, and for the 76,999 and ninety metre figures, “Asase mo kui 1.3 man bon, nanjaku jiban koji kei 7.6 man bon Boei kyoku hokokusho de hanmei,” Ryukyu shimpo, 9 February 2019. For analysis in English, Hideki Yoshikawa, “Abe’s military base plan sinking in mayonnaise: Implications for the US Court and IUCN,” The Asia-Pacific Journal – Japan Focus, 15 February 2019.

Abe to the Diet on 30 January 2019: “Koki ya hiyo ni tsuite kakutaru koto o moshiageru koto wa konnan.”

Okinawa prefecture (Washington DC office), “Concerns for environmental impacts of seabed improvement work in land reclamation in Henoko,” 17 July 2019.

The sea-level around Okinawa has risen at the average rate of 2.2 mm per year since 1954, slightly less than the global average but at rising rate. (Okinawa kishodai, “Okinawa no kiko hendo kenshi ripoto, March 2019)

Lawrence Wilkerson, former senior adviser to Colin Powell in George W. Bush administration in the early 1990s, quoted in “Koron, Henoko, Beikoku kara mita rorensu uirukuson, jamesu schoff san,” Asahi shimbun, 22 February 2019.

“Henoko de 7 do-me no saiban’ kosei de jisshitsuteki na shinri wo,” ed, Okinawa taimusu, 18 July 2019. For text of the dossier.

“Ikkatsu kofukin no kakuju o, hoshukei 8 shicho de tsukuru ‘chimu Okinawa’, jiminto ni yosei,” Okinawa taimusu, 3 September 2019.

“Henoko isetsu no sokushin motomeru ketsugi, Ginowan shigikai ‘gaman genkai’,” Asahi shimbun, 27 September 2019.

To the Foreign Correspondents Club of Japan on 9 November and to New York University on 11 November. See discussion in Kihara Satoru, “Okinawa, Bei sentoki FA18 no suiraku wa nani o shimesu ka,” Ari no hitokoto, 15 November 2018.

“Naha gunko no Urasoe isetsu-an, Okinawa-ken, Naha-shi, Urasoe-shi ga kento kaigi setchi de goi,” Okinawa taimusu, 25 October 2019.

“Tamaki Deni-shi, Jieitai to Beigun no kichi kyodo shiyo kyogi mo, intabyu de hyomei, okinawa ken chijisen,” Sankei shimbun, 2 October 2018.

“International Scholars, peace activists, and artists condemn agreement to construct US marine base in Okinawa,” 7 January 2014.

Hideki Yoshikawa, “Abe’s military base plan sinking in mayonnaise: Implications for the US Court and IUCN,” The Asia-Pacific Journal – Japan Focus, 15 February 2019. See also Yoshikawa’s “Dugong swimming in uncharted waters: US judicial intervention to protect Okinawa’s ‘natural monument’ and halt base construction,” The Asia-Pacific Journal – Japan Focus, 2009, and his “Jugon saiban: Jugonen no kei-i to kongo no tembo,” Kankyo to kogai, October 2018, pp. 29-33.

For a critical discussion from an Okinawan NGO, environmental movement perspective, Okinawa Environmental Justice Project, op. cit. See also Hideki Yoshikawa, “Hesitant Heritage: US bases on Okinawa and Japan’s flawed bid for World Natural Heritage status,” Asia-Pacific Journal – Japan Focus, 15 April 2019.

The Government of Japan, “Nomination of Amami-Oshima Island, Tokunoshima Iland, the Northern Part of Okinawa Island, and Iriomote Island [for UNESCO World Natural Heritage],” January 2019.

With the discovery of one dugong corpse (Individual B) in March 2019, and absence of any sightings of A and C over the past year, the IUCN is expected to adopt the category “critically endangered” which many will take to be synonymous with extinct. “’Dugong zetsumetsu ka’ koji o tome zenken chosa o,” editorial, Okinawa taimusu, 13 October 2019.)

The US-based Center for Biological Diversity has served notice of its intent to file suit against the US government (the Fisheries and Wildlife Service in the Department of the Interior) for failure to protect the Okinawa Woodpecker [Noguchigera] living in the forest area in the vicinity of the US Northern Training Area.

“For Henoko land reclamation, Prime Minister Abe claims, ‘The coral there is being relocated,’ however the reality is no such activity is taking place in the landfill area,” Ryukyu shimpo, 8 January 2019.

The Editorial Board, “Toward a smaller American footprint on Okinawa,” New York Times, 1 October 2018.