Abstract

Prime Minister Abe Shinzō’s anticipated trip to St Petersburg and Moscow at the end of May 2018 represents the culmination of his “new approach” to Russia. Unveiled two years earlier, this policy seeks to achieve a breakthrough in the countries’ long-standing territorial dispute by reducing Japan’s initial demands and offering incentives in the form of enhanced political and economic engagement. Having stuck resolutely with this policy despite criticism from the West, Abe now needs it to deliver, not least to boost his flagging approval ratings. This article highlights exactly what the Japanese leader hopes to achieve and assesses his prospects of success. Particular emphasis is placed on the proposed joint economic activities on the disputed islands and the specific legal obstacles that need to be overcome.

Japan, Russia, Japan-Russia, Northern Territories, Kuril Islands, Prime Minister Abe

On May

Abe’s “new approach”

Although Abe has been consistent in his desire for closer relations with Japan’s northern

In practice, this “new approach” features two elements. First, it entails a moderation of Japan’s immediate territorial demands. Traditionally, Japanese governments have insisted on the return of all four of the disputed islands as a bunch, a policy known as “yontō

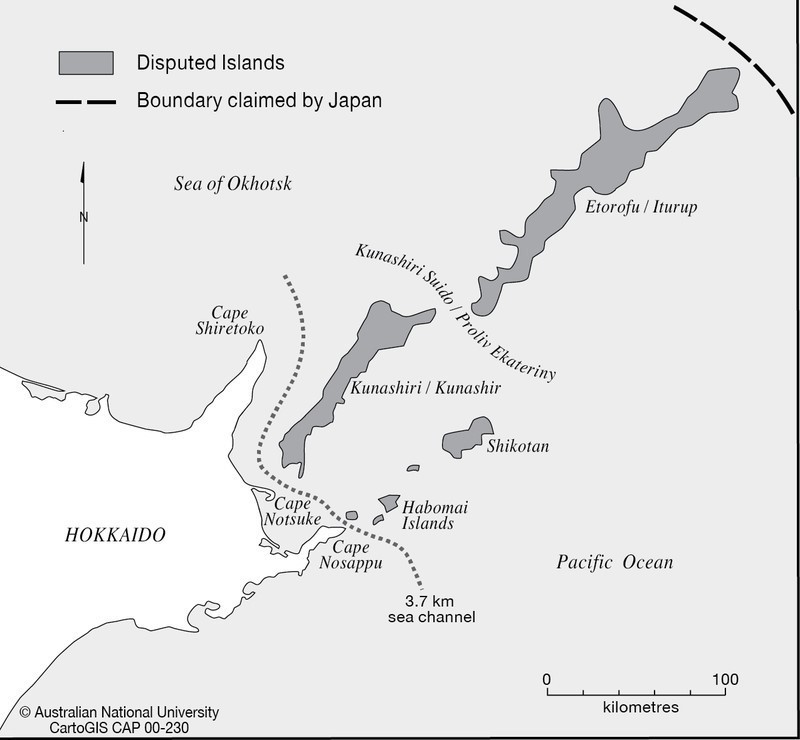

|

Map of the disputed islands (Source |

The second aspect of the “new approach”

This rapprochement has been contentious since it has taken place at a time of profound tension between Russia and the West over issues including Moscow’s intervention in Ukraine, its support for the Assad regime in Syria, its alleged interference in the 2016 U.S. presidential election, and its suspected use of a nerve agent in the attempted assassination of former Russian spy Sergei Skripal and his daughter in Salisbury (U.K.) in March 2018. The U.S. government has

This places Japan in an awkward position. On the one hand, the Abe administration remains determined to persist with the “new approach” and to take advantage of what is perceived to be an opportunity for progress on the territorial issue. Yet, on the other, the Japanese government wishes to avoid the appearance of there being too much distance between its own foreign policy and that of its crucial U.S. ally and other Western partners.

This difficult balancing act has been most evident in Japan’s response to the Skripal case. Following this incident on 4 March, the U.K. government “concluded that it is highly likely that Russia was responsible,” describing it as the “unlawful use of force by the Russian state against the United Kingdom” (Hansard 2018). In response, London expelled 23 Russian diplomats who were described as undeclared intelligence officers. In the subsequent days, the U.K.’s position was endorsed by international partners and a total of 28 countries expelled more than 150 Russian diplomats. The notable exception was Japan, which neither supported the U.K.’s allegations against Russia nor joined in the expulsion of Russian diplomats. Instead, the Abe administration was only willing to state that “Japan’s view is that use of chemical weapons is unacceptable … and Japan hopes to see clarification of the facts as early as possible” (MOFA 2018b). This prompted praise from the Russian ambassador in Tokyo, who stated that “The point of view of the Japanese government on this issue has much in common with Russia’s position.” (TASS 2018d).

This stance only changed towards the end of April when, fearing isolation at the G-7 foreign ministers’ meeting in Toronto, Japan signed up to the group’s joint statement on the Salisbury attack, which explicitly identifies Russia as the likely culprit (Gov.uk 2018). Although Ambassador Galuzin expressed sadness at seeing Japan’s signature on this document (TASS 2018e), the Abe administration will hope that their late endorsement of the U.K.’s position and continued refusal to consider diplomatic expulsions will signal that their change in policy was a reluctant concession to Western pressure. This echoes Japan’s response to Russia’s annexation of Crimea in March 2014. At that time, although Tokyo did ultimately follow Western partners in imposing sanctions, it was slow to act and the measures introduced were considerably weaker than those of other G-7 members. Moreover, despite giving rhetorical support for Ukraine’s territorial integrity and condemning changes to the international status quo by force, the Abe administration soon made clear its eagerness to resume rapprochement with Russia.

The timing of Abe’s “new approach” may appear puzzling since

|

Figure 2: Commander in chief of the Russian army Oleg Salyukov test drives a Type-10 tank during his visit to Japan in November 2017. (Source: JGSDF) |

The second explanation is that the Abe government evidently concurs with the view that the present time is “a historic window of opportunity” to improve Japan-Russia relations and achieve a breakthrough on the territorial issue (Togo 2017). This is based on the assumption that Russia’s post-Crimea isolation, as well as the economic difficulties it has suffered due to Western sanctions and low oil prices, could cause Moscow to place greater value on economic and political cooperation with Japan, thereby making territorial concessions more likely. Added to this, there is the belief that Putin has a positive attitude towards Japan, based on his passion for judo and friendships with former Prime Minister Mori Yoshirō and judo legend Yamashita Yasuhiro. It is also known that Putin’s daughter Katerina studied Japanese at St Petersburg University (Grey et al 2015). Additionally, Putin is seen as possibly the only Russian leader with sufficient strength to face down

Based on these assumptions, optimists will see the May 2018 summit as particularly propitious. Following the Skripal case and the introduction of a fresh set of U.S. sanctions on 6 April, Russia’s isolation from the West has further deepened, making Japan’s status as an outlier within the G-7 all the more appealing to Moscow. Additionally, the summit follows soon after Putin’s official inauguration as Russian president on 7 May. This is deemed significant since it should represent the start of Putin’s final term in office. With the Russian leader

Encouraged by such thinking, the Japanese government has pulled out the stops in preparing for the summit. This began at the start of the year when Abe used his speech at the opening of parliament to state that “The relationship between Japan and Russia has the most potential of any bilateral relationship.” (Kantei 2018). Following the Russian election, Abe was also quick to call Putin to offer his congratulations and to reconfirm his determination to advance bilateral relations (MOFA 2018a). Just two days after the vote, Foreign Minister Kōno welcomed his Russian counterpart Sergei Lavrov to Japan where the sides agreed to hold a strategic dialogue between First Deputy Foreign Minister Vladimir Titov and Vice Minister for Foreign Affairs Akiba Takeo on 19 April. It was also announced that further bilateral security talks between Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov and Senior Deputy Foreign Minister Mori Takeo would take place in Tokyo in May, while a third “2+2” meeting would be scheduled for the second half of 2018. Linking these agreements with his government’s political agenda, Kōno declared that “security dialogue is important to deepen mutual understanding between Japan and Russia and to move towards concluding a peace treaty.” (Nikkei 2018).

There was a further burst of activity at the end of April when Liberal Democratic Party (LDP)

|

Foreign Minister Kōno Tarō hosts Russian counterpart Sergei Lavrov in Tokyo on 21 March 2018. (Source: The Japan Times) |

Further to these political and economic preparations, the Japanese side has worked to cultivate a friendly atmosphere in bilateral ties. This included giving Foreign Minister Lavrov a birthday cake shaped like a football during his visit to Tokyo in March. At the end of April, it was also announced that Viktor Ozerov is one of four Russians to be presented this year with the Order of the Rising Sun, a national

Domestic political considerations also play a role in the Abe administration’s desperation to ensure that the May summit proves a success. Persistent accusations of scandal have sapped Abe’s approval rating and he has recently suffered foreign policy setbacks, an area previously seen as a strength. Specifically, Japan has been sidelined from the pageant of summitry occurring around the Korean peninsula and, despite Abe’s fawning efforts to cultivate close personal ties with President Trump, the U.S. administration refused to grant Japan an exemption on steel and

What Abe hopes to achieve in May

Since the visit is intended to celebrate the Year of Japan-Russia, Prime Minister Abe will firstly be aiming for a symbolic demonstration of his success in forging a relationship of personal trust with the Russian leader. This has been a consistent feature of Abe’s Russia policy, though he has not yet found the right formula for developing personal chemistry with Putin. For instance, the Russian leader has not been enthusiastic about Abe’s proposal that they refer to each other as “Vladimir” and “Shinzō”. Ahead of his visit to Japan in December 2016, Putin also declined Abe’s offer of an Akita puppy and he arrived at the summit nearly three hours late.

Aside from achieving more positive optics on the relationship between the two leaders, the Japanese side will be aiming to announce an impressive slate of economic agreements at the St Petersburg Economic Forum on 25 May. This will demonstrate the results of two years of work on the 8-point economic cooperation plan. It will also serve as a prelude to the next day’s talks in

Prime Minister Abe would dearly love this to be the moment when a deal on the status of the islands is finally

At present, the supposedly “inherent” Northern Territories are almost entirely disconnected from the rest of Japan. Since the expulsion of Japanese residents by the Soviet Union after 1945, the islands have had no settled Japanese population. There are also no Japanese businesses operating there and the Japanese government discourages citizens from visiting other than via a fixed number of official visa-free trips that take place each summer. With the territory having been under Moscow’s control for almost 73 years, few Japanese remain with any direct experience of having lived on the islands. As such, the Abe administration fears that, unless connections are re-established quickly, the islands’ estrangement from Japan will become complete.

Abe’s access policy has two specific components. The first is to make it easier for the former residents and their relatives to visit the islands. The existing system, which has operated since 1992, enables relevant Japanese citizens to visit the islands without the need of a visa, which would acknowledge Russian authority. To make the system reciprocal, Russians now living on the islands are permitted to visit Japan under the same conditions. These annual summer visits are conducted using the Etopirika, a Japanese passenger ship that is based at Nemuro, the closest Hokkaidō port to the disputed islands. These trips can be very time-consuming, not least because it has been the practice for all entry procedures to be conducted at sea at a point near Kunashir/i. This means that, even when traveling to one of the other islands, all visitors must go by way of Kunashir/

|

The Etopirika, which is used for visa-free visits to and from the Southern Kurils/Northern Territories. (Source: www.marinetraffic.com) |

While hosting Putin in Japan in December 2016, Abe made an appeal on humanitarian grounds for Russia to ease the burden for remaining Japanese islanders who wish to continue visiting their former homeland. This included handing over a letter that had been written by the former residents. This approach proved successful and in April 2017 it was agreed that an additional maritime entry point would be opened closer to the Habomai Islands. It was also decided that a visit for former residents would be permitted by airplane. Initially scheduled for June 2017, this special flight was postponed due to bad weather and only eventually took place in September.1 Abe’s aim for the May summit will be to ensure that these new arrangements continue in 2018 and beyond.

The second element of the access policy is the proposal for joint economic activities on the islands. This is the core of Abe’s “new approach” and it is on this basis that the results of his Russia trip should be judged. The proposal for joint economic projects is not new; in fact, it was proposed by Russian Foreign Minister Evgenii Primakov during a visit to Tokyo in November 1996. At the time, the Japanese side was hesitant, fearing that an agreement on joint economic activities would effectively mean shelving the sovereignty dispute. Others worried that Japanese investments might be confiscated or argued that contributing to the development of the islands would simply reinforce the Russian occupation (Kimura 2000: 191-199). Abe appears to share no such concerns,

Although many observers considered Putin’s visit to Japan in December 2016 to be a disappointment, it did result in a formal agreement to discuss joint economic projects. Subsequently, survey trips to the islands by officials and business figures from each side were conducted in June and October 2017. Further apparent progress was achieved during Abe’s visit to Vladivostok in September that year when the leaders agreed on five initial candidate projects. These are aquaculture, greenhouse agriculture, tourism, wind power, and waste reduction (MOFA 2017).

The individual projects are economically small-scale and may even prove lossmaking. Their significance is in the fact that it has been announced that these joint economic activities will be conducted “under a special arrangement”, meaning “legal frameworks that will not harm the positions of either side” (MOFA 2016b; 2017). This has been interpreted as indicating the Russian government’s willingness to permit Japanese businesses to operate on the islands without having to be subject to Russian jurisdiction (Shimotomai 2016). This would indeed represent a major change since Moscow would essentially have conceded that the islands are distinct from the rest of Russian territory and that Russian sovereignty over them is not absolute. Abe would also have achieved a level of access that far exceeds the current situation, enabling Japanese businesses and individuals to re-establish a permanent presence on the islands for the first time in seven decades.

If Abe can return from Moscow with a signed agreement committing the sides to conducting joint economic activities under such a legal framework, this would represent a significant diplomatic achievement. It would not, however, bring an end to the territorial dispute. Prime Minister Abe has not abandoned the goal of seeing the eventual return of the disputed islands, and, by opening the door to a revival of Japanese influence, the joint economic projects are viewed as a stepping stone towards achieving this.

Intriguingly, Iwata Akiko, a journalist who is said to be close to Prime Minister Abe, has described the joint economic activities as actually “the start of a step by step setting up of a framework for Russia-Japan cooperation after the border’s establishment” (Iwata 2018). This seems to suggest that, having initially served as a system to enable a Japanese presence to operate on the islands while they remain under Russian control, the special legal framework could ultimately function as a mechanism to permit the continuation of Russian involvement on the islands after a transfer of the territory to Japanese control. This would, in theory, assist Japan in dealing with the issue of the Russian citizens that would remain on the islands following their return to Japanese sovereignty.1

Can Abe succeed?

With regard to the symbolic component, the celebration of the Year of Japan-Russia should provide ample opportunities to showcase the friendly nature of bilateral ties and the appearance of close personal relations between Abe and Putin. Indeed, the problem may be that a display of too much camaraderie with the Russian leadership could attract criticism from the West. This issue may be magnified by President Macron’s attendance at SPIEF. On the one hand, the decision of the French leader to attend the economic forum provides cover for Abe to do the same. At the same time, Macron has demonstrated a willingness to speak truth to powerful leaders, including condemning Russian state-media for “spreading propaganda” while standing next to President Putin (Chassany and Hille 2017). If the French president does something similar in St Petersburg, for instance by publicly criticising Russia for interference in foreign elections or the Skripal case, it will draw attention to Abe’s silence on these matters and make the Japanese leader look weak.

The situation may also not be plain sailing when it comes to economic cooperation. During Minister Sekō’s visit to Russia at the end of April, he met with Minister for Economic Development Oreshkin and Minister of Energy Novak, as well as First Deputy Prime Minister Shuvalov, and undoubtedly the sides will have found some promising-sounding deals to announce during Abe’s visit. The question, however, is how many of these agreements will prove substantive.

Since its unveiling in May 2016, the 8-point economic cooperation plan has led to an uptick in bilateral economic activities. In particular, Sekō has drawn attention to a licensing agreement between Japan’s Otsuka Pharmaceutical and Russia’s R-Pharm, as well as growing cooperation between Japan’s National Centre for Child Health and Development and Russia’s Dmitry Rogachev National Research Centre of Pediatric Hematology, Oncology

Each of these projects no doubt has merits, but so far the results of the 8-point plan are modest and they certainly do not seem to justify the appointment of their own cabinet minister. It has also been reported that, of over 100 agreements signed between the sides, only 40% are actually being considered for implementation (Ōmae 2018). This slow pace of progress is causing frustration on the Russian side, with most politicians seeming to have limited interest in the small-scale practical schemes being proposed by Japan and preferring to

A sense of disappointment is also discernible among Japanese investors who feel that not enough has been done to ease their concerns about operating in Russia. This sentiment was expressed by Asada Teruo, head of Marubeni and chair of the Japan-Russia economic commission for Keidanren, Japan’s business federation. Addressing the Russia-Japan Forum in April, Asada described the strength of the economic relationship as unsatisfactory and pointed to the need for infrastructure improvements in the Russian Far East (Mainichi 2018). This suggests that the Abe administration’s enthusiasm for economic cooperation with Russia is not shared by

Given this context, it is probable that Abe’s attendance at SPIEF will not be accompanied by the signing of transformational, billion-dollar deals. This may be a point of regret for both sides, yet it is not necessarily that much of a problem for Abe since the economic dimension of his “new approach” has always been presented as a means to securing political ends. As such, if

With regard to the territorial dispute, some progress should be relatively easy. Specifically, there should be few problems in agreeing to conduct further flights to the islands and continuing to operate the additional maritime entry point near Habomai, at least while the Japanese former residents remain alive. Further details about the five priority projects may also be announced and it may be agreed that a third joint survey visit will be conducted later in 2018. However, as noted, the crux of this issue is the legal question and there are serious doubts that the Russian government is really willing to permit Japanese entities to operate on the disputed islands under a system distinct from Russian law.

Despite optimistic Japanese assessments of the agreement reached in December 2016, there have long been indications that the Russian government’s understanding of the “special arrangement” under which joint economic activities would be conducted is not the same as Japan’s. Indeed, at the very time the agreement was announced, Kremlin foreign policy aide Yurii Ushakov insisted that these projects would be conducted under Russian law (Takenaka and Golubkova 2016). More recently, Foreign Minister Lavrov has stated that “We do not see the need to create some type of supranational body,” placing emphasis instead on “the current regime, including the benefits of the Vladivostok Free Port and the regime of the territory of advanced socio-economic development” (TASS 2018a). This indicates that the Russian leadership wishes the joint economic activities to be conducted within its special economic zones (known as TORs), which operate under Russian law. One such TOR was created on the island of Shikotan in August 2017. Generally, however, Lavrov was reluctant to address legal specifics, saying that “The focus should not be an obsession with the legal side of the matter but, above all, on joint economic activity – this is the essence of the agreement.” (TASS 2018a). A bilateral working group was convened on 11 April to address the evident gap between the sides on this matter, but it failed to achieve concrete progress (Mainichi 2018a).

Russia has therefore shown little inclination to compromise on the most important legal question. Instead, Russian politicians have sought to encourage Japan to invest under Russian law, warning that, if Japan does not proceed quickly, Russia will solicit investment from other countries (Podobedova 2018). This threat appeared to be carried out when, in March 2018, Sakhalin Governor Kozhemyako announced that an unnamed U.S. firm had agreed to invest in a diesel power plant on the island of Shikotan (News24.jp 2018). The Russian side also appears eager to press forward with the details of the joint economic projects, thereby making it harder for the Japanese side to walk away if their legal demands are not met.

|

|

Despite employing these tactics, the Russian authorities can have little expectation that the Japanese government will agree to invest in joint economic projects on the islands if they are subject to Russian jurisdiction. This would represent a reversal of decades of Japanese policy. Instead, the Russian leadership will know that some form of compromise will be required if the economic projects are actually to go ahead. One possible model is the bilateral fishing agreement of 1998. This allows Japanese fishing boats to operate in the waters surrounding the disputed islands in accordance with annual agreements that set quotas and levels of payment. Crucially, this agreement includes an article specifying that,

“Nothing in this Agreement, nor any activities conducted in accordance with this Agreement, nor any measures taken to implement this Agreement nor any activities or measures related thereto shall be deemed as to prejudice the positions or views of any Party with respect to any issues of their mutual relations.” (MOFA 2001).

This serves to clarify that the agreement does not constitute Japan’s

Although a similar clause would help facilitate the joint economic projects in 2018, the issue is more complex when it relates to activities conducted on the disputed land itself. Not least, there is the matter of passports and visas. To address this problem, Russian officials recently floated the idea of creating a visa-free zone that would apply to all of Hokkaidō and the Sakhalin region, which administers the disputed islands (Hokkaidō Shinbun 2018; TASS 2018b). Such an arrangement would eliminate many problems. It would enable Japanese citizens to freely visit the islands without acknowledging Russian sovereignty, thereby achieving Abe’s goal of

Such a visa-free zone really would be transformative, yet it would be an enormous step for Prime Minister Abe to agree to such a mechanism, especially given Japan’s traditional aversion to immigration. The total population of the Sakhalin region is approximately half a million and many Japanese citizens would be concerned that there would be an influx of Russians into Hokkaidō. Some Japanese might believe that this would lead to an increase in crime and that, even with official time limits, the Russian visitors might seek to settle permanently. There would also be no easy way of preventing Russian visitors from

Domestic critics would also point to the fact that Russia has recently proceeded with strengthening its military presence on the disputed islands and has conducted several military exercises in the area this year, including in April (Sherunkova 2018). In the same month, it was also reported that the Japanese Self-Defence Forces scrambled jets on 390 occasions in fiscal 2017 to intercept Russian aircraft, an increase of 89 from a year earlier (Johnson 2018). In this context, those in Japan who do not share the prime minister’s passion for relations with Russia would argue that Japan is rewarding Russia despite its unwillingness to make real concessions on the territorial issue and despite its continuation of hostile activities in the vicinity of Japan. This is to say nothing of the likely response from Western powers who are already frustrated by the softness of the Abe administration’s stance on Russia.

It is impossible to entirely rule out a surprise outcome at the May summit. In particular, the Russian side may judge it expedient to permit Japan to make some gains. This would give Abe something to sell domestically, thereby raising the chances of his pro-Russian policy continuing. However, given the legal obstacles and the fact that Abe is unlikely to agree to an extensive visa-free zone, the most likely result is a summit that delivers little beyond a few symbolic images, some vague economic promises, and an agreement to continue working on the joint economic activities. This is an outcome that is largely satisfactory to the Russian side since they remain in control of the islands and they gain a certain international legitimation by Abe’s diplomatic efforts. By drawing out the dispute for as long as possible, the Russian leadership also ensures that Japan will continue to have reasons to court Russia through promises of economic cooperation and by distancing itself from

|

A breakthrough remains unlikely when Abe and Putin meet for the 21st time in May 2018. (Source: TASS). |

Conclusion

Coming two years after the introduction of his “new approach” and timed to coincide with the Year of Japan-Russia, Abe’s visit to St Petersburg and Moscow at the end of May represents the moment of truth for his Russia policy. Driven by concerns about the increasingly close ties between Russia and China as well as by Abe’s desire to leave his personal stamp on history, the “new approach” has sought to achieve a breakthrough in the dispute over the Southern Kurils/Northern Territories by lowering Japan’s initial demands and offering economic incentives as well as expanded political engagement. The Japanese leader has also shown determination in sticking with this policy despite it leading to frictions with Japan’s Western partners, especially over the Skripal incident. And yet, for all the efforts that have been made in building up to this summit, the likelihood is that Prime Minister Abe will return disappointed.

The Japanese government will be sure to put a positive spin on even the most

In the short term, Russian diplomats can feel pleased

James Brown is Associate Professor in Political Science at Temple University, Japan Campus. His main area of expertise is Russia-Japan relations. His research has previously been published in International Affairs, International Politics, Politics, Asia Policy, Post-Soviet Affairs, Problems of Post-Communism, Europe-Asia Studies, and The Asia Pacific Journal: Japan Focus. His book publications include Japan, Russia

Related articles

• James D.J. Brown, Abe’s 2016 Plan to Break the Deadlock in the Territorial Dispute with Russia

• James D.J. Brown, Not Even Two? New developments in the territorial dispute between Russia and Japan

• Tsuneo Akaha and Anna Vassilieva, Breaking the Impasse in Japan-Russia Relations

Works cited

Brown, James D.J. (2017). Japan, Russia

Chassany, Anne-Sylvaine

Fedotova, Anastasia. (2018, April 20).

Gov.uk. (2018, April 17). G7 foreign ministers’ statement on the Salisbury attack.

Grey, Stephen, Kuzmin, Andrei, and Piper, Elizabeth. (2015). Putin’s daughter, a young billionaire and the president’s friends. Reuters.

Hansard. (2018). Salisbury incident. Volume 637, column 620-621.

Hokkaidō Shinbun. (2018, April 11). Nichiro kankei ‘hiyaku-teki hatten mo’ [Japan-Russia relations are ‘developing rapidly’].

Interfax. (2017, September 6). Russia, Japan seriously considering Hokkaido-Sakhalin bridge project – Shuvalov.

Iwata, Akiko. (2018, January 11). A New Step Forward to “Regions for Japan-Russia Cooperation” — results and challenges from the Japan-Russia summit. Discuss Japan, no. 42.

Izvestiya. (2018, May 4). Zamglavy

Japan Times. (2018, January 6). Japan might ask Russian President Vladimir Putin to visit in 2019 to discuss isle row.

Johnson, Jesse. (2018, April 14). Chinese military aircraft flew over strategic waterway record number of times in fiscal 2017, Japan Defense Ministry says. Japan Times.

Kantei. (2018, January 22). Policy Speech by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe to the 196th Session of the Diet.

Kimura, Hiroshi. (2000). Distant Neighbors: Volume 2 – Japanese-Russian Relations Under Gorbachev and Yeltsin. London: Routledge.

Mainichi. (2018a, April 11) Kyokuchō-kyū sagyō

Mainichi. (2018b, April 28). Nihon roshiafōramu Nikai jimintō kanji-chō ga kōen [Japan-Russia Forum: LDP Secretary General Nikai gives a speech].

MOFA. (2011, March 11). Agreement between the Government of Japan and the Government of the Russian Federation on some matters of cooperation in the field of fishing operations for marine living resources.

MOFA. (2016a, May 7). Japan-Russia summit meeting.

MOFA. (2016b, December 16). President of Russia visits Japan.

MOFA. (2017, September 7). Japan-Russia summit meeting.

MOFA. (2018a, March 19). Nichiro shunō

MOFA. (2018b, March 27). Press Conference by Foreign Minister Taro Kono.

News24.jp. (2018, March 13). Hoppōryōdo no Shikotantō de Amerika kigyō ga

NIDS. (2016). East Asian Strategic Review.

Nikkei (2018, March 21). Nichiro kyōdō

Ōmae, Hiroshi. (2018, April 2). Nichiro keizai kyōryoku [Japan-Russia economic cooperation]. Mainichi Shinbun.

Podobedova, Lyudmila. (2018, February 1). Trutnev

Ponomareva, Natal’ya. (2018, March 19). Vzaimovygodnaya

RIA Novosti. (2018, April 24). Pravyashchaya v Yaponii LDP

Sherunkova, Ol’ga. (2018, April 19). Yaponiya

Shimotomai, Nobuo. (2016). New Japan-Russia

Takenaka, Kiyoshi

TASS. (2017, August 30). Former residents of South Kuril Islands set off on

TASS. (2018a, March 16). Lavrov: RF

TASS. (2018b, March 21). Lavrov

TASS. (2018c, March 22). Press review: Russia-Japan ties backslide and Tatar radicals fail to sway

TASS. (2018d, April 3).

TASS. (2018e, April 18).

Togo, Kazuhiko. (2017, August 31). Domestic dalliances

Tōkyō Shinbun. (2018, May 3). Nichiro kyōryoku jigyō

U.S. Department of Defense. (2018). Summary of the 2018 National Defense Strategy.

U.S. Treasury. (2018, April 6). Treasury Designates Russian Oligarchs, Officials, and Entities in Response to Worldwide Malign Activity.

Notes

The two largest of the islands are known as Iturup and Kunashir in Russian, Etorofu and Kunashiri in Japanese. The smaller islands of Shikotan and the Habomais have the same names in both languages. The Habomais are actually a group of islets but, for convenience, it is customary to refer to a four island dispute.

Announced in May 2016, the eight-point plan envisages increased Japan-Russia cooperation in “(1) Extending healthy life expectancies, (2) developing comfortable and clean cities easy to reside and live in, (3) fundamentally expansion [sic] medium-sized and small companies exchange and cooperation, (4) energy, (5) promoting industrial diversification and enhancing productivity in Russia, (6) developing industries and export bases in the Far East, (7) cooperation on cutting-edge technologies, and (8) fundamentally expansion [sic] of people-to-people interaction” (MOFA 2016a).

Even when the charter flight did eventually take place in September, it did not proceed smoothly. As scheduled, the plane took half of the Japanese visitors to Kunashir/i, before proceeding with the rest of the group to Iturup/Etorofu. However, due to bad weather, the return flight from Iturup/Etorofu had to divert to Sakhalin, leaving half of the party stranded on Kunashir/i where they had to spend the night, before returning to Hokkaidō by boat.