Abstract: This article examines photographs taken by U.S. Marine Joe O’Donnell, who was tasked with documenting bombed urban centers immediately after the Asia-Pacific War. O’Donnell’s photos document not just the physical damage wrought by U.S. bombing raids, but the human suffering as well. While most published images at the time projected the U.S. military’s destructive potential through mushroom clouds or razed cities, O’Donnell shifted the visual focus to the struggles of Japanese citizens in the ruins. In doing so, O’Donnell disrupted notions of American superiority by giving voice to those rebuilding their lives in the war’s aftermath.

Keywords: photography, postwar, Allied Occupation of Japan, Asia-Pacific War

“The Army of the Occupation is extensively armed—with Kodaks, Leicas and Speed Graphics…”

So wrote Lucy Herndon Crockett, who served with the Red Cross during World War II and then in the first years of the Allied Occupation of Japan (1945–1952) (Crockett 1949: 99). The “extensively armed” Army of the Occupation, as Crockett phrased it, produced a dizzying array of photographs that portrayed complex—and constantly shifting—images of Japan. Those who believed in the superiority of American democracy foregrounded the process of democratization and demilitarization that they were helping to implement, as well as evidence of the American cultural influences seen as crucial to those efforts. Many captured various aspects of traditional Japanese culture, ranging from Kabuki performances to koi (carp) kites flapping lazily in the wind, and on to sumo wrestlers practicing in their stables. Others documented resort town respites, producing idyllic scenes seemingly out of place in a country that was otherwise devastated, defeated, and under occupation. As the so-called “reverse course” set in and Occupation policies shifted from reforming a wartime enemy to bolstering a Cold War ally, GIs produced photos of cultural exchange that symbolized friendship and goodwill. And many Americans documented extensively their daily life as part of the Occupying forces, capturing scenes of daily life amidst newly built schools, theaters, churches, and post exchange (PX) stores brimming with consumer goods on U.S. military bases.

Then there was Marine Joseph (Joe) O’Donnell, who was tasked with documenting the results of U.S. incendiary and atomic bombing raids. O’Donnell arrived in Japan still harboring the hatred that had propelled him into war after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, but his animosity dissipated as he encountered bombed cities and those living in them through the act of photo-taking (O’Donnell 2005: xiii). Focusing on the relationship between space and photography, I argue that the spatial conditions of Japan’s ravaged cities are crucial to understanding how O’Donnell viewed Japan and its people, and the meaning that emerged from his photos (Smylitopoulos 2016). According to visual arts scholar Jack Richardson, “the subject in space, the material and social conditions of the space, and the other images and subjects that circulate within that space” interact with one another to construct meaning (2006: 63). Similarly, art historian Joan M. Schwartz has argued that “value-laden visualizations of people(s), place(s), and the relationship(s) between them” transform “‘space’ on the ground into ‘place’ in the mind” (2011: 4). In other words, as a form of representation, photographs construct meaning related to landscape, identity, power, and control. In O’Donnell’s case, his experience navigating the ruins and meeting the people who inhabited them caused his hatred and antipathy to transform into forgiveness and empathy. This, in turn, engendered a shift in his photographs from a focus on the triumph of the U.S. military to the plight of the humanity around him.

As a cultural historian interested in how visual culture shapes notions of belonging and otherness, political and social engagement, and subjectivity, a key area of my current research investigates how Americans and Japanese engaged with one another through photography in ways that reinforced, challenged, or circumvented America’s occupying authority. The few studies on Allied photographers suggest that Americans viewed Japan through an Orientalist lens that rendered the Japanese people feminized, non-threatening, and subordinate (Shibusawa 2006; Low 2015; Miles and Gerster 2018). While this argument holds true in some cases, it reinforces the idea that the Allied Occupation was defined solely by an Occupier-Occupied hierarchical relationship—a dynamic that scholars have recently begun to challenge (Koikari 2015; Hein 2018). O’Donnell’s assignment as a photographer permitted him to travel freely, a freedom not often afforded to other Occupation personnel (O’Donnell 2011). The Marine even had himself photographed, demonstrating that he not only gazed at but actively engaged with the people he photographed. O’Donnell’s photos are thus important because they illuminate how the act of photo-taking transcended the conventional dichotomy between Occupier and Occupied, fostering shared experiences between Occupation personnel and Japanese citizens.

O’Donnell’s photographs hold additional significance for the emerging field of nuclear humanities (Nayar 2022). As N.A.J. Taylor and Robert Jacobs argue, the past, present, and future existence of nuclear technologies necessitates an ongoing process of “experiencing and re-imagining Hiroshima,” extending beyond the temporal confines of the twentieth century to render Hiroshima relevant to contemporary discourse (Taylor and Jacobs 2018: 2). O’Donnell’s photobooks are unique because they integrate in one visual space the irradiated landscapes of Hiroshima and Nagasaki with cityscapes that had been devastated by incendiary bombing raids. This synthesis is of particular relevance in a contemporary world characterized by the mounting threat of nuclear warfare (Nuclear Threat Initiative) and the continued use of incendiary weapons despite their regulation under Protocol III to the Convention on Conventional Weapons (CCW) (Human Rights Watch 2018). In O’Donnell’s photos, the plight of humanity within the irradiated and scorched ruins reminds us that these scenes are not confined to history, but rather, continue to inform our present in many places around the world today.

In the following, I examine O’Donnell’s photographs, published in two photobooks in 1995 and 2005, to show how space shaped O’Donnell’s perceptions of and interactions with the Japanese, prompting him to prioritize the human condition over manifestations of American superiority. I first introduce O’Donnell, contextualize the broader historical backdrop of the Allied Occupation, and briefly trace the history of O’Donnell’s photographs. I then undertake a close analysis of his photos, and conclude with brief remarks on the importance of examining photographs depicting the atrocities of war, past and present.

The Photographer and the Ruins

Joe O’Donnell, born in Johnstown, Pennsylvania in 1921, enlisted in the U.S. Marines after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941. This event propelled the U.S. into what John Dower has termed a “war without mercy” in the Pacific Theater of World War Two, characterized by deeply ingrained racial animosities on both sides and exceptionally brutal combat.1 Like many of his compatriots who sought retribution against Japan for what they perceived as a cowardly sneak attack, O’Donnell enlisted in the armed forces “full of anger towards the Japanese” (O’Donnell 2005: xiii). To his dismay, he found himself assigned to the 5th Division as a photographer. The only shooting O’Donnell would do during the war was through the lens of a camera.

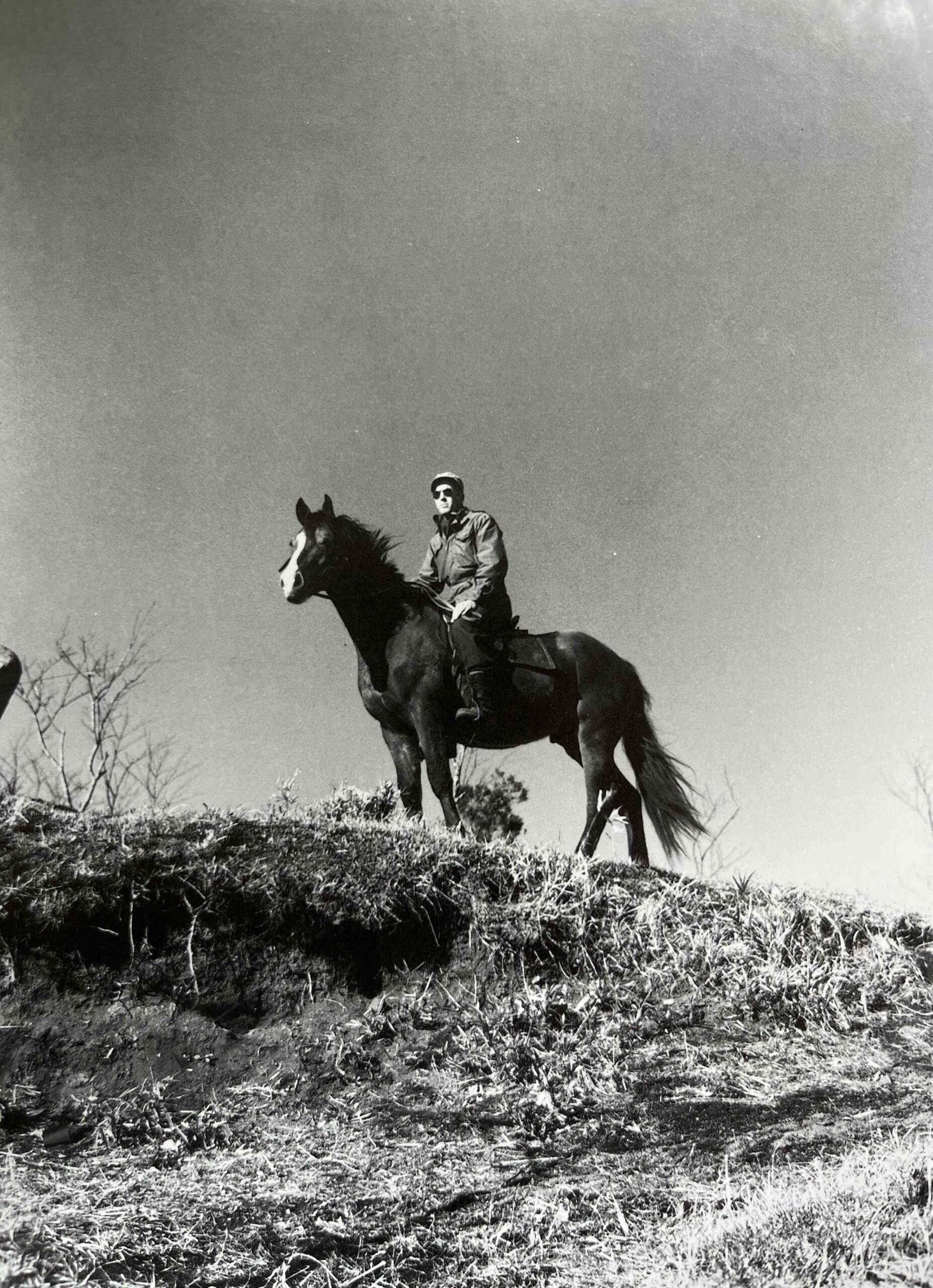

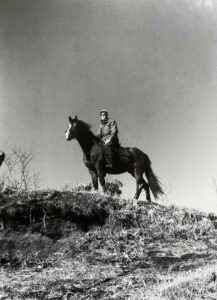

Following Japan’s surrender, O’Donnell received orders to document the results of U.S. bombing raids on Japan’s urban centers. He spent seven months traveling throughout Japan, sometimes in a jeep with a Japanese-American interpreter, but most of the time on his horse, Boy, to avoid stepping on human bones that littered the landscape (Nashville WWII Stories 2007) (figure 1).2 His travels took him to Sasebo and Fukuoka, two cities that had been subjected to incendiary bombing raids in 1945, and to the atomic fields of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The Japanese had a word to describe the desolate landscapes of their once-vibrant cities that became the subject of O’Donnell’s photos: yakeato. Burned ruins. Much of this destruction resulted from U.S. firebombing campaigns in the last years of the war. By one estimate, U.S. bombs, not including the nuclear attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, destroyed between fifty and ninety-eight percent of sixty-six Japanese cities, killing more than 300,000 people and leaving over eight million people homeless (Selden 2007; Kerr 1991: 280-81). With their homes destroyed, people found shelter in shacks cobbled together from debris, subway stations, and even busses turned into makeshift homes.

Japan’s devastated cities were only one aspect of the social, political, and cultural upheaval that beset the defeated nation. In addition to the housing crisis, one of the chief challenges was a lack of food. Ten people died of starvation per day in late 1945, and the average height and weight of school children declined steadily until 1948 (Gordon 2013: 226). Urban residents were forced to rely on black markets to supplement food rations; in most cases, Occupation forces supplied the goods sold in black markets (Kōsei 2022: 1051). Children orphaned by the war wandered the streets, frequently caught in weekly roundups by Occupation and Japanese authorities, only to run away days later.3 Prostitution became a steady source of income for many women and some men, and visibly wounded, white-robed repatriated soldiers begged in the streets (Gordon 2013: 226). The repatriation of over six million military personnel from Japan’s former empire exacerbated the severe material shortages and economic inflation that affected almost every aspect of society (Takemae 2003: 110). Numerous social problems proliferated as a result: alcohol and drug abuse increased, as did rates of robbery and theft (Gordon 2013: 227).

The arrival of the Allied Occupation compounded the chaotic conditions of the immediate postwar years. The Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP) went to great lengths to ensure that the war Japan had waged would be its last by pursuing demilitarization and democratization policies: promoting land reform and redistribution, dismantling industrial and financial conglomerates (zaibatsu), introducing universal suffrage, and writing a new Constitution for Japan. Article Nine of the Constitution renounced war and banned Japan from maintaining any type of armed forces. Emperor Hirohito disavowed his divinity, transforming from a divine sovereign who ruled over Japanese subjects to a figurehead who drew his power from the sovereignty of Japanese citizens. In short, SCAP instituted sweeping reforms to dismantle Japan’s military government and set the stage for the creation of a new democratic polity.

In addition to imposing a new political system, SCAP endeavored to democratize Japan by establishing American cultural hegemony.4 As one example, Occupation officials, keenly aware of the power of entertainment, used Hollywood films to offer up American culture as a benchmark of civilization and cultural enlightenment (Kitamura 2012: 141). At the same time SCAP placed heavy censorship constraints on Japanese film, photography, and other media. The Civil Censorship Detachment (CCD) scheduled regular meetings for the Japanese press to make it clear that SCAP’s goals extended beyond censoring taboo material to actively shaping what was produced and published (Braw 1991: 40). Toward this end, it established the Civil Information and Education Section (CI&E) as a mouthpiece of American propaganda. Directing a range of institutions (e.g., the Japanese press, schools, libraries, and churches), and employing a range of media (e.g., film, radio, and print publications), the CI&E aimed to “remake Japanese thinking” and “impress war guilt on the nation” (Fainsod 1946: 294). O’Donnell certainly knew about the stringent control of the media, having befriended a Japanese photographer who had warned him to guard his negatives lest the U.S. military confiscate his film and cameras (“A Straight Path Through Hell” 2005).5

O’Donnell documented the yakeato armed with a military-issued camera, but he took his personal photographs with a camera he purchased from a small shop that had miraculously survived the bombings. When he entered the store, O’Donnell was shocked to find it fully stocked with cameras, lenses, filters, and film, and was ecstatic to find all the merchandise easily affordable. When he pulled out his wallet to make a purchase, however, the shopkeeper asked if he could pay with cigarettes instead. Astounded by the stack of cigarettes O’Donnell piled on the store counter, the shopkeeper offered the Marine his pick of the most high-end cameras in the store: an American-made Speed Graphic and a German-made Rolleiflex (O’Donnell and Alldredge 1995: 18).

Now armed with a personal camera, O’Donnell took photographs of ravaged cityscapes and the people who inhabited them. Initially, Japanese civilians avoided O’Donnell’s camera, but he discovered that they would pose for him in exchange for chocolate, gum, and cigarettes. Starving children, in particular, flocked to O’Donnell when he called out “chocoletto” (“A Straight Path Through Hell”). There was only one problem: strict regulation of the black market prohibited openly carrying such items. Luckily for O’Donnell, the accordion of his camera provided the perfect hiding place, which proved so successful that the Marine considered buying another camera just to hide the contraband (O’Donnell and Alldredge 1995: 28). Whether it was the generous act of sharing food or the ever-present gnawing hunger that overcame the fear of O’Donnell’s presence, in either case, the camera was central to fostering engagement between O’Donnell and the Japanese people. Once O’Donnell took their pictures, the Japanese often peppered him questions, and O’Donnell recounts that many children followed him as he went about his work (O’Donnell 2005: 35, 84).6

The wreckage, hardship, and misery that O’Donnell witnessed impacted him deeply. “The people I met, the suffering I witnessed, and the scenes of incredible devastation taken by my camera caused me to question every belief I had previously held about my so-called enemies,” he wrote. “I left Japan with the nightmare images etched on my negatives and in my heart” (O’Donnell 2005: xiii). As these “nightmare images” were precisely the type that censors targeted, O’Donnell had to sneak his negatives out of Japan by packing them in a box labeled “photography paper: do not expose to light,” thereby ensuring that they would not be discovered during inspection (Grulich 2007). Upon returning home, however, O’Donnell found himself unable to look at his pictures. He locked them in a trunk, where they remained untouched for nearly fifty years.

After a long career as a photographer, O’Donnell retired on a medical disability caused by radiation exposure. Not long after his retirement, O’Donnell attended a religious retreat at the Sisters of Loretto Motherhouse in Nerinx, Kentucky. While at the retreat, O’Donnell encountered a life-sized sculpture of a burned man on a cross created by a resident nun in memory of the victims of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It recalled to the former Marine the destruction he had seen, and since tried to forget. “I felt everything from inconsolable grief to violent outrage,” stated O’Donnell. “So much horror, so much waste, so much inhumanity to innocent people . . .” (O’Donnell 2005: xiii). O’Donnell purchased the sculpture and, upon returning home, unlocked the forgotten trunk and took out the negatives taken with his private camera, hidden away for so many years.

To help organize his photographs—and to confront his nightmarish memories—O’Donnell enlisted the help of a friend, Jennifer Alldredge. For O’Donnell, the process of reliving his time in Japan served a purpose beyond mere catharsis. The former Marine believed it was his mission in life to show the world what he had witnessed and experienced in Japan, particularly to “remind people of the realities of what happened in Japan the summer of 1945, to tell the story of what lay beneath the mushroom cloud, always left untold” (O’Donnell 1995: 115). O’Donnell first told his story through a small traveling exhibition at museums, churches, and universities throughout the United States, Europe, and Japan. Many considered the traveling exhibition a healing ministry of sorts that paid tribute to those who perished in the bombings, as well as to the hibakusha—the survivors who endured social stigmatization in Japan.7

In 1995, O’Donnell’s photographs were selected to accompany an exhibit at the National Air and Space Museum on the Enola Gay, the B-29 Superfortress bomber that dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima. Originally included to depict the aftermath of the bombings, his photos and other similar visual and textual depictions of the bombs’ devastating effects met with swift criticism. Monroe W. Hatch Jr., the executive director of the Air Force Association, excoriated the exhibit, asserting that it favored Japan and neglected to address Japanese aggression and atrocities (Atomic Heritage Foundation 2016). Veteran and military groups also protested the planned exhibit, claiming that O’Donnell’s photos presented an unfair view by overlooking the bombs’ perceived role in ending the war (Martin 2007). Even the U.S. Senate intervened, denouncing the exhibit as “revisionist and offensive to many World War II veterans” (Senate Resolution 257, 1994). Consequently, O’Donnell’s photos were removed from the exhibit. The revised script downplayed the effects of the bombs on Hiroshima’s citizens, even excluding photographs of human casualties (Atomic Heritage Foundation). According to his widow, O’Donnell was so frustrated over the affair that he went to the exhibit and kicked the Enola Gay. Twice (Graulich 2007).

In the same year that curators removed O’Donnell’s photos from the Enola Gay exhibit, Shogakkan Press published his photos in the Japanese-language photobook Japan 1945, Images from the Trunk (Toranku no naka no Nihon: Beijūgun kameraman no hikōshiki kiroku). Ten years later, Vanderbilt University Press republished the book in English with twenty additional photographs under the title Japan 1945: A U.S. Marine’s Photographs from Ground Zero. Far removed from the hatred that initially drove him to enlist for the war, O’Donnell’s photographs evoke, as one viewer observed, a sense of compassion for those who experienced the tremendous destructive power of the atomic and incendiary bombs (O’Donnell 2005: vii). A disorienting sense of crisis emerges from photos of unimaginable devastation; yet at the same time, the photos display the steadfast endurance of the Japanese. Ultimately, O’Donnell’s photosconvey unsettling yet compelling moments, building a narrative centered on suffering and hardship, yet also portraying a resilient people rebuilding their lives.

The Photographer in the Ruins

In Japan 1945, five chapters take the viewer through O’Donnell’s journey across Japan: the first documents his arrival, while the subsequent four bear witness to the shattered cities of Sasebo, Fukuoka, Hiroshima, and Nagasaki.8 The pictures O’Donnell took with his personal camera place humanity—the dead as well as the living—within the scorched ruins. This stands in stark contrast to photographs in American news media and government studies conducted shortly after the bombings; in both instances, the human presence was glaringly absent. Classified reports and studies meticulously document the built environment—or what remained of it—but elided the plight of the people who had occupied it.9 In instances where the human victims were depicted, the photographs offered only close-ups of injuries or portrayed the subject against blank or neutral backgrounds. Humanity, in these photos, was reduced to little more than gruesome medical conditions (Army Medical College).

American media projected the military might of the U.S. with towering atomic mushroom clouds and aerial panoramas of sprawling, flattened cityscapes. In the 20 August 1945 issue, Life magazine reproduced photos of mushroom clouds alongside text proclaiming the world to have been “shaken by the new weapon” dropped by American planes (“War’s Ending”: 25). Notably, the article on the bombs in this issue obscures the civilian inhabitants of both cities, describing Hiroshima as “a major Japanese port and military center” and Nagasaki as a “shipbuilding port and industrial center.” Additional photos in the issue included before-and-after renditions of Hiroshima from an aerial perspective—one that appeared again in other issues. In an essay entitled “U.S. Occupies Japan,” for example, photos of cities flattened by incendiary bombing raids underscored American military prowess, but the aerial perspective elided the plight of the people who lived in these cities (“U.S. Occupies Japan”). Such photos stopped short of showing the bombs’ toll on humanity that was so central to O’Donnell’s photos.

Censorship did not prohibit outright photographers from recording bombed cities. Life photographer Alfred Eisenstaedt (1898–1995) photographed women praying in a ruined cemetery, for example, and Bernard Hoffman (1913–1979) recorded people walking among completely flattened landscapes. Hoffman later wrote that he took such photos, not out of compassion for the Japanese who lived among the ruins, but rather to record the destructive power of the atomic bomb. In a telegram to Life picture editor Wilson Hicks (1897–1970), Hoffman expressed that “most of us felt like weeping” upon seeing Hiroshima for the first time, though “not out of sympathy for the Japs, but because we were shocked and revolted by this new and terrible form of destruction” (Cosgrove). In one disturbing scene, Hoffman photographed a skeleton resting amidst the debris. The curve of the spine, propped up by the ribcage jutting out of the ground, leads the eye to the partial remains of a church looming in the distance.10 Life never printed this photograph, nor did they publish others like it.

J. R. Eyerman (1906–1985) also submitted photos of Hiroshima to Life that evidenced widespread ruin and suffering, but those photos did not appear in his photo story published in Life’s 8 October 1945 issue. Instead, the story adopted the perspective of a travel narrative, plying readers with scenes of bustling train stations, crowded train cars, and rich landscapes viewed from the train window. Photos show children walking the streets with no visible injuries, and demobilized soldiers posing shirtless, their robust bodies projecting an image of health and youthful vigor. Were it not for two photographs of Japanese citizens physically scarred by bombings printed on the final page, the story would have elided the atomic destruction entirely. But the caption disrupts the seemingly sympathetic image of suffering. Placed underneath the photo of a mother and child with visible burns, it reads: “Photographer Eyerman reported their injuries looked like those he had seen when he photographed men burned at Pearl Harbor” (“The Tokyo Express” 1945: 34). By casting the bombing as a righteous act of retribution, the caption diminished the humanity of the subjects and dismissed their scars of war.

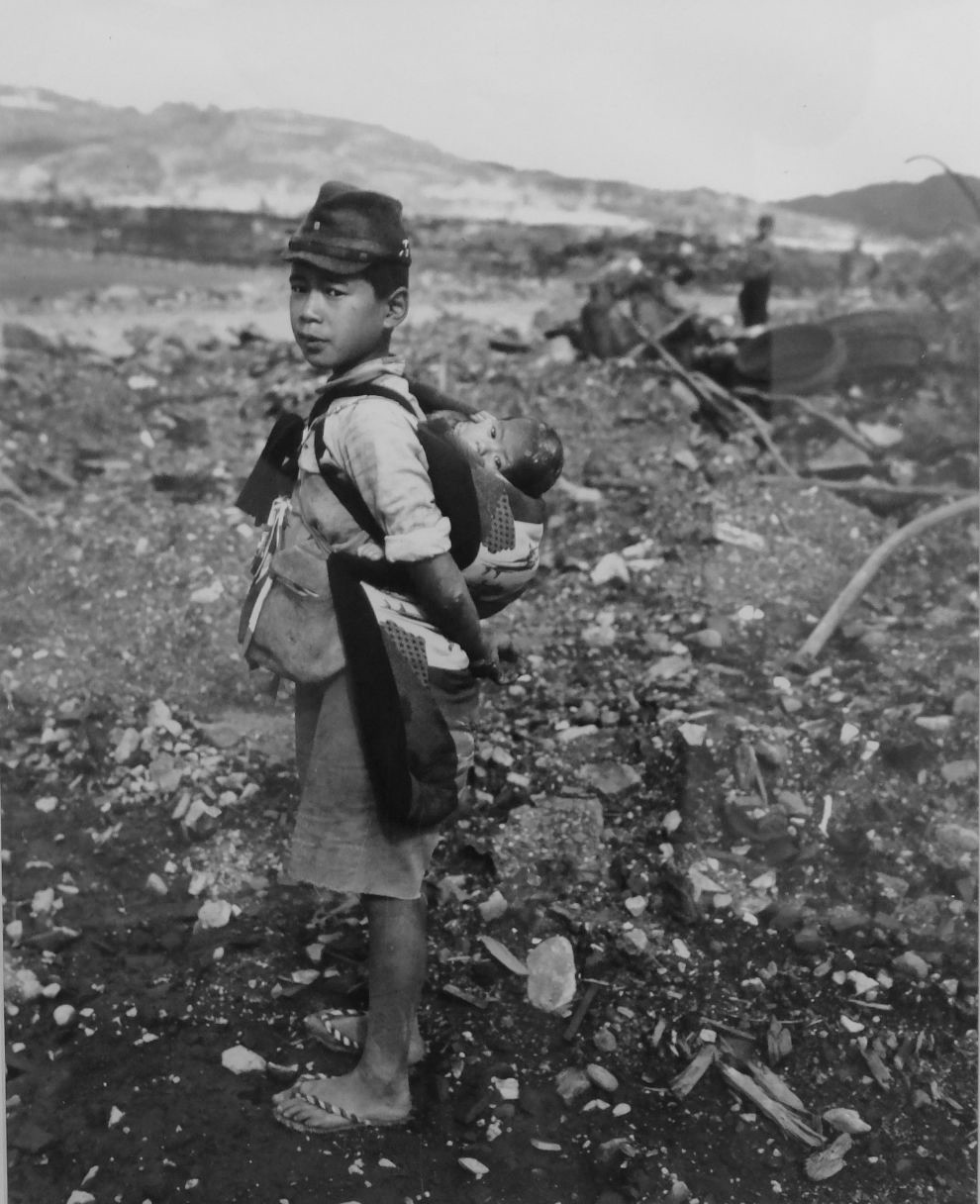

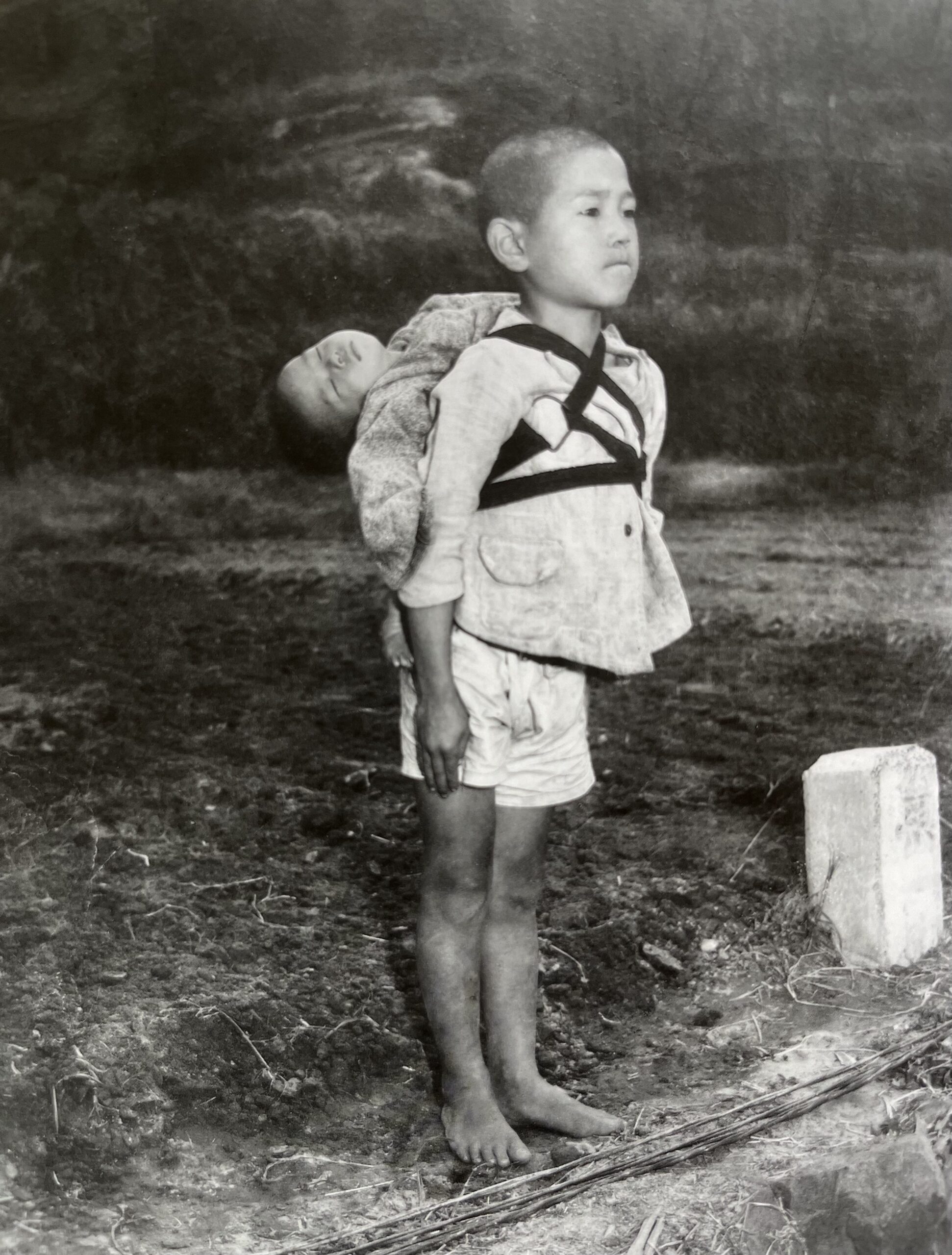

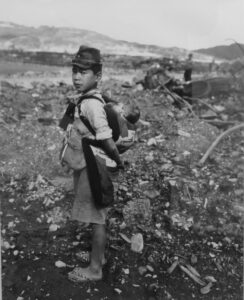

In stark contrast to the images that circulated in American media, O’Donnell highlighted humanity in the photos that he took of urban destruction. His emphasis on the Japanese people is made clear by the very first photograph in his book. A young boy stares out from the front cover of Japan 1945 (figure 2). The youth carries his baby brother on his back, wrapped in a warm blanket. After taking in the rest of the older boy’s appearance, from his military cap to his sandals, the viewer’s eye moves restlessly over the rest of the frame. Dark tonal values and deep contrasts create a haunting, gritty impression. The photographer literally enfolds the subject within the space of the ruins. The wreckage becomes so dominating that it competes with the boy for prominence. It might even overwhelm the youth were it not for the vertical line created by his erect form. The boy’s upright posture and solid stance create a strong visual force that anchors the eye. He is slight and disheveled, surrounded by chaos, yet stands erect in a manner that allows him to rise above the ruins radiating around him.

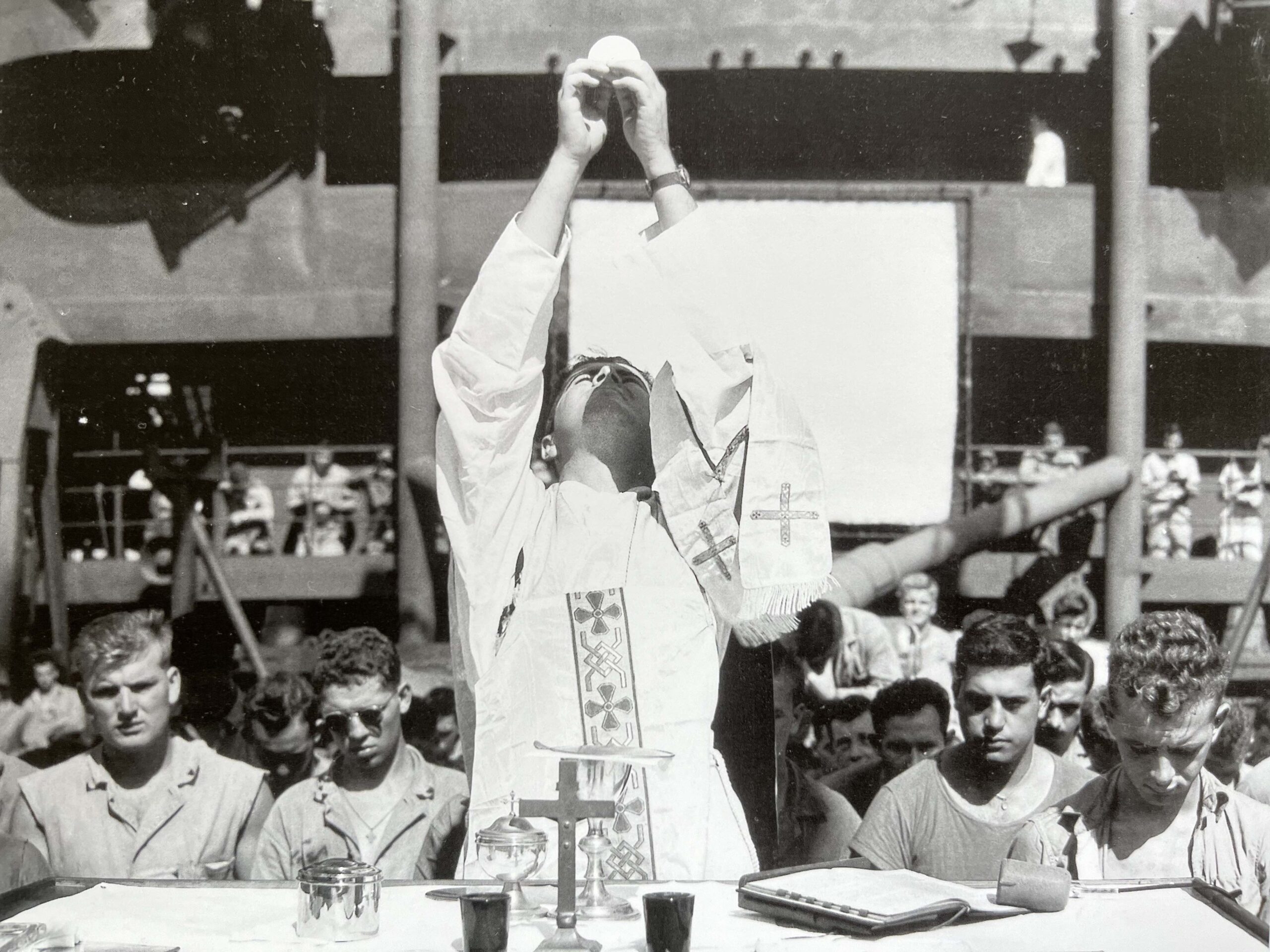

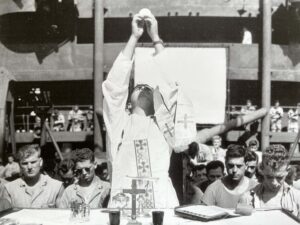

If the cover photo of this war orphan takes the viewer straight to the heart of O’Donnell’s experience in Japan, the first chapter brings the viewer back to the beginning of his journey. Opening the book, the viewer first moves through four photographs that comprise the chapter “Landing.” The first two photos project a highly religious tone, a motif that crops up repeatedly throughout the rest of the book. Marines gather around a priest in the first photo, a figure almost lost in the crowd of men. Turning the page, the viewer next gets a close-up view of the priest (figure 3). O’Donnell placed him centrally within the frame and in sharp focus. The priest looks towards the heavens with his arms outstretched above his head and the afternoon sun sets his white robes ablaze, providing a contrast against the muted grays of the men and the battleship that fill the rest of the frame. Both photos are flooded with bright sunlight.

The final two photos in the chapter show a colonel briefing troops aboard the ship before landing at Sasebo, and then a landscape shot of military vehicles filling up Sasebo’s beaches. O’Donnell received orders to make first landing so that he could document the troops, tanks, jeeps, and other vehicles as they arrived on the beach. As he stood on the shore, a Japanese man in military uniform emerged from the brush and approached him. Alone and unsure what to do, O’Donnell accepted a folded Japanese flag from the man, who said that he belonged “to the Imperial Army coming here to surrender.” Shortly afterward, American troops began piling military equipment on the beach, a process that filled the surrounding area with thunderous sounds as “wave after wave of tanks and other equipment rolled ashore” (O’Donnell 2005: 6).

Turning next to the chapter on Sasebo, the viewer sees another landscape, this time of rolling hills and terraced rice fields rising above Sasebo harbor—an expanse of water filled with an “American black ship armada,” as O’Donnell put it. Sasebo attracted the attention of U.S. military strategists due to its importance as one of the four main naval bases in Japan, as well as its proximity to a nearby coalfield. On 30 March 1945, eighty-five B-29 bombers dropped mines into the eastern approach to the Shimonoseki Strait (the channel between Honshū and Kyūshū), preventing reinforcements and supplies from reaching Sasebo and other vital ports (Craven and Crate 1953: 668). Then, just after midnight on 29 June 1945, the U.S. conducted the first bombing raid on the city. The aircraft targeted several military installations, including an aircraft assembly plant and the Sasebo Aircraft Factory (Sasebo Report No. 3, 1945). In an attack that lasted less than ninety minutes, over 1,200 Japanese were killed and forty-two percent of the city was destroyed (Center for Research: Allied POWS Under the Japanese). Seven more air raids followed, each adding to the destruction and death toll.

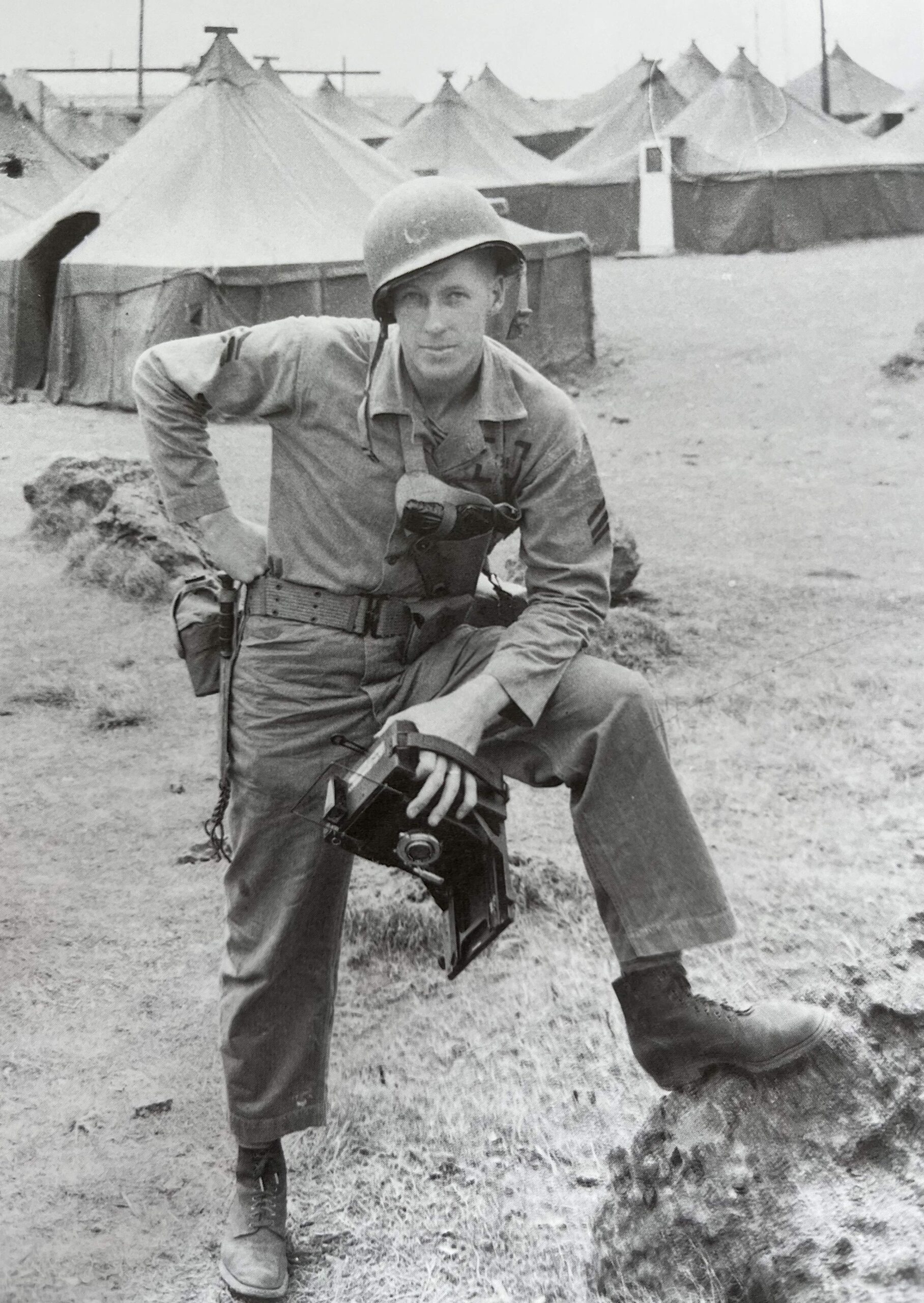

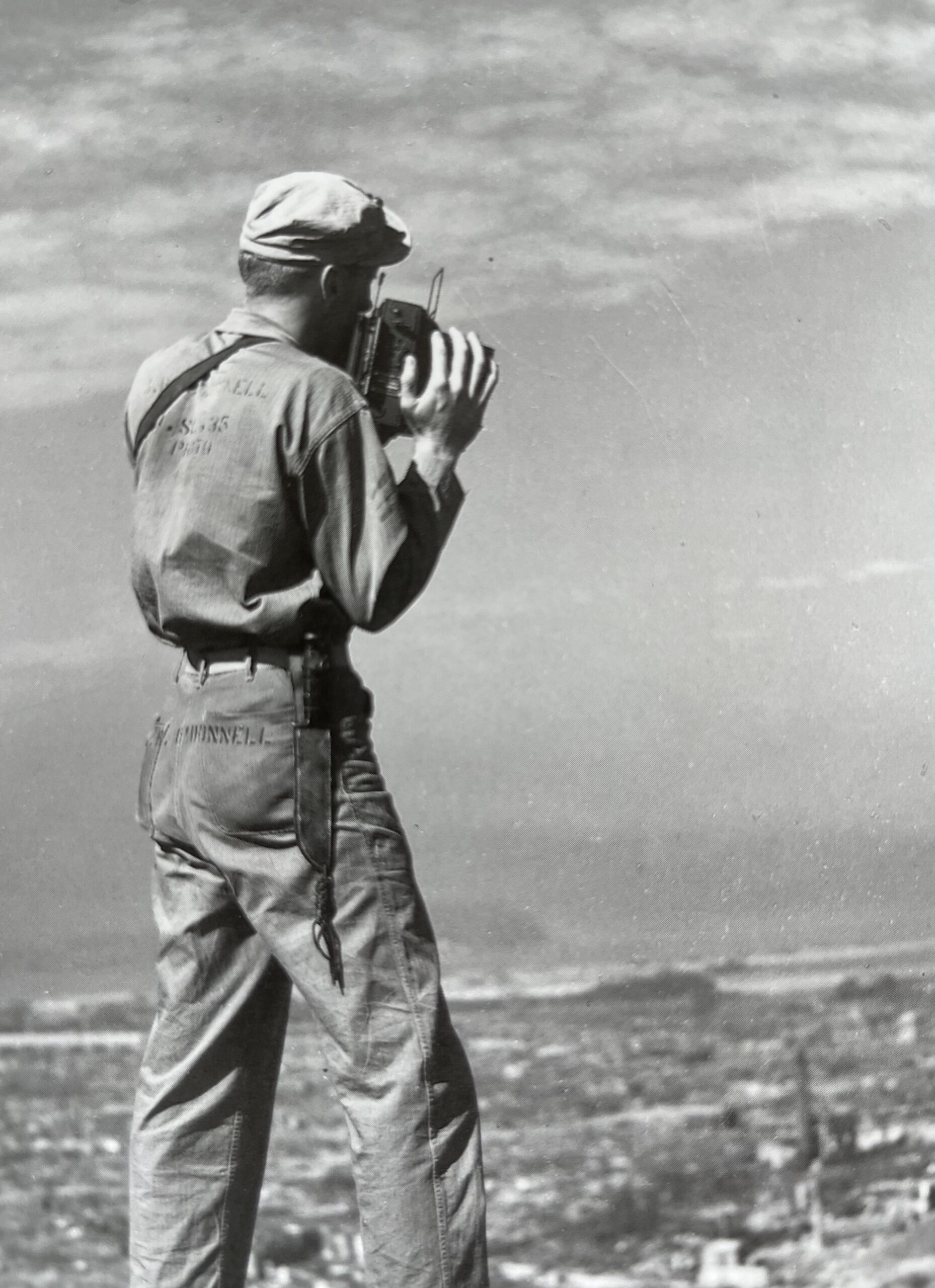

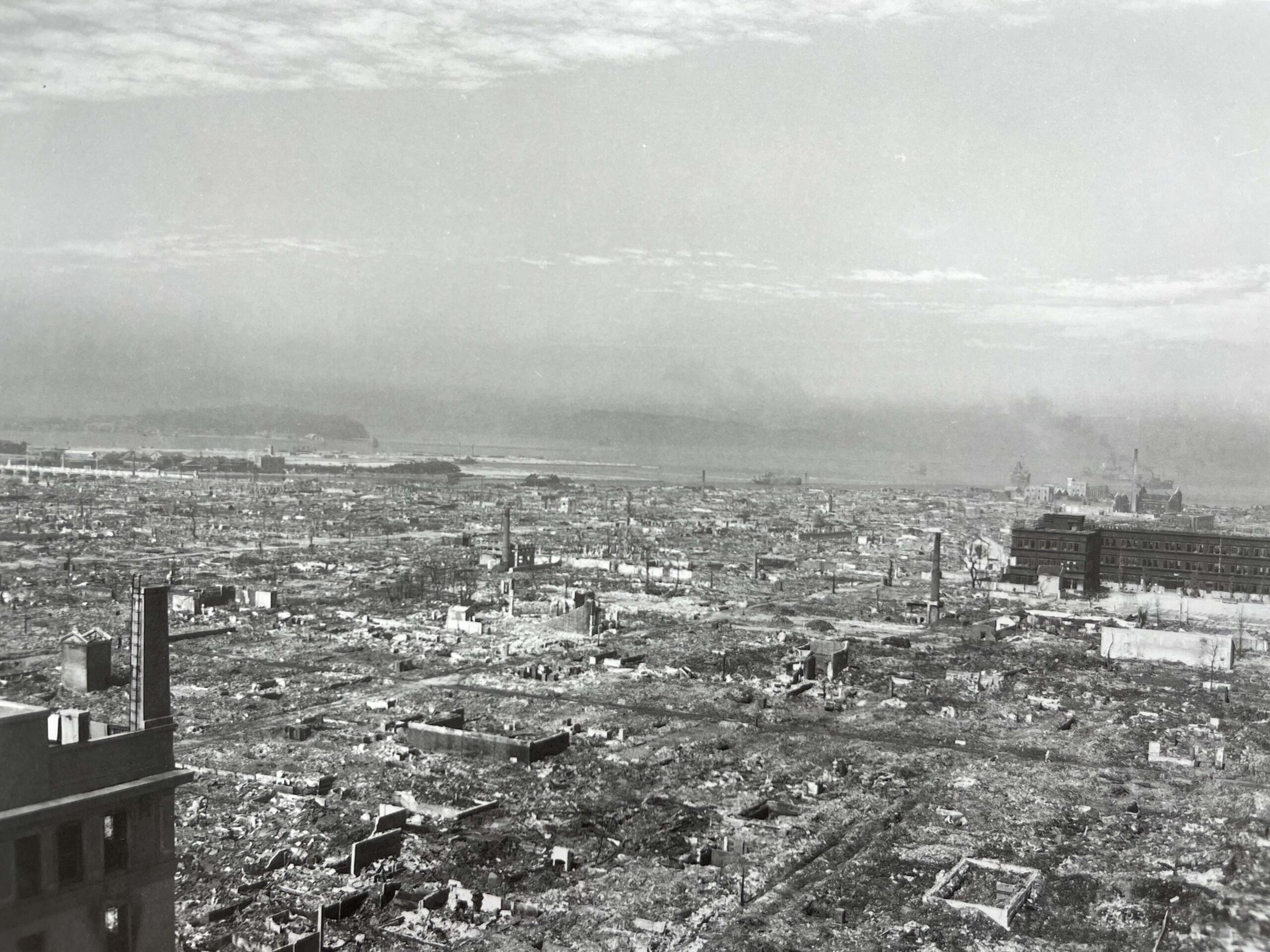

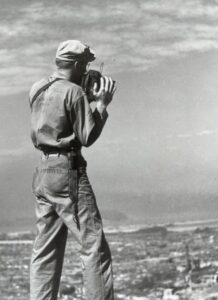

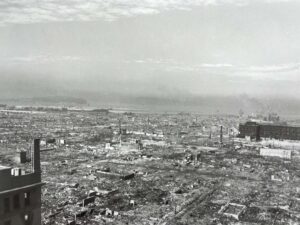

To get a panoramic view of the devastated city, O’Donnell climbed to the roof of one of the few remaining structures. In Japan 1945, he explains that tall ferroconcrete buildings had acted like a giant oven when the bombs hit and fire washed over Sasebo, trapping people inside and burning them alive. Blackened bodies clogged the stairways and halls afterward, and the stench of burned flesh that still lingered in and around the building nearly overpowered O’Donnell as he struggled to climb twelve flights of stairs. When he reached the roof, the photographer had his first unobstructed view of the ruins he was tasked to document. A sequence of three photographs captures the scene (figure 4). Moving from left to right, the viewer sees two pictures of O’Donnell himself and then a panorama of Sasebo. In the first photo, the photographer stands centrally framed in front of canvas military tents. Helmet askew, O’Donnell leans forward toward the camera, with one leg planted firmly on the ground and the other resting comfortably on a mound of dirt. His stance projects a dominant, cocksure attitude, and he further shows that he is ready for action by placing one fisted hand against his hip while firmly gripping his camera with the other. The photograph encapsulates his role not only as a photographer but also as a participant in his story. Here, he is a young man of the victorious Occupation forces.

The middle picture evinces a subtle shift in O’Donnell’s body language. Here he stands on a ledge looking out at the landscape beyond. If the first photo conveys commanding authority and readiness for action, the second betrays some ambivalence. The Marine now wears a cloth cap instead of a helmet, his shoulders droop, and his camera falls away from his face, as if he needs to see the landscape with his own eyes to believe what he sees. What had captured O’Donnell’s attention appears in stark clarity in the third photo. The horizon cuts through the center of the frame, separating a hazy sky from the devastated city below. A few structures still stand here and there, but the photo captures a chaotic mess of rubble and debris stretching from one side of the frame to another. This sequence of photographs and the accompanying captions tell a story within a story, revealing O’Donnell’s transformation from a man confident in his role as a U.S. Marine to one shaken by the devastation that stretched out before him. For O’Donnell, the definitive moment came when he was faced with a razed environment filled with human casualties of war. The experience clearly changed his thinking about the people and the nation he had been ordered to photograph.

Subsequent photographs in the Sasebo chapter convey the devastation that O’Donnell witnessed as he moved through the grim landscapes. Dark, foreboding clouds hang low over barren streets and charred trees. Families search for new places to live, carrying the few belongings they still owned. Women lug baskets full of rations, flanked by leveled buildings and blackened trees. Children swarm around a Marine sitting on the hood of his jeep, handing out chocolate and chewing gum to the hungry youth with outstretched hands. Quotidian moments punctuate these more somber scenes: young Japanese women hired as maids pose outside the Marine barracks in Sasebo, and a farmer harvests rice in a sunny field (figure 5).

O’Donnell even discovered a grave marked by a wooden cross and fresh flowers as he moved through the city. Seeking out the story behind the burial mound, shock washed over O’Donnell when he learned that a Japanese couple had reverently buried an American pilot who had died during the Doolittle Raid (O’Donnell 2005: 21).11 A second photo shows the couple posing with pieces of the plane that they had saved and wrapped in woven straw. When O’Donnell asked the couple why they bothered to bury the man, they responded simply that they respected him as one of the dead. The spatial grounds of the burial site and the empathetic act that created it moved O’Donnell, marking his steady transformation from a detached military observer into a man who harbored growing compassion toward a former enemy.

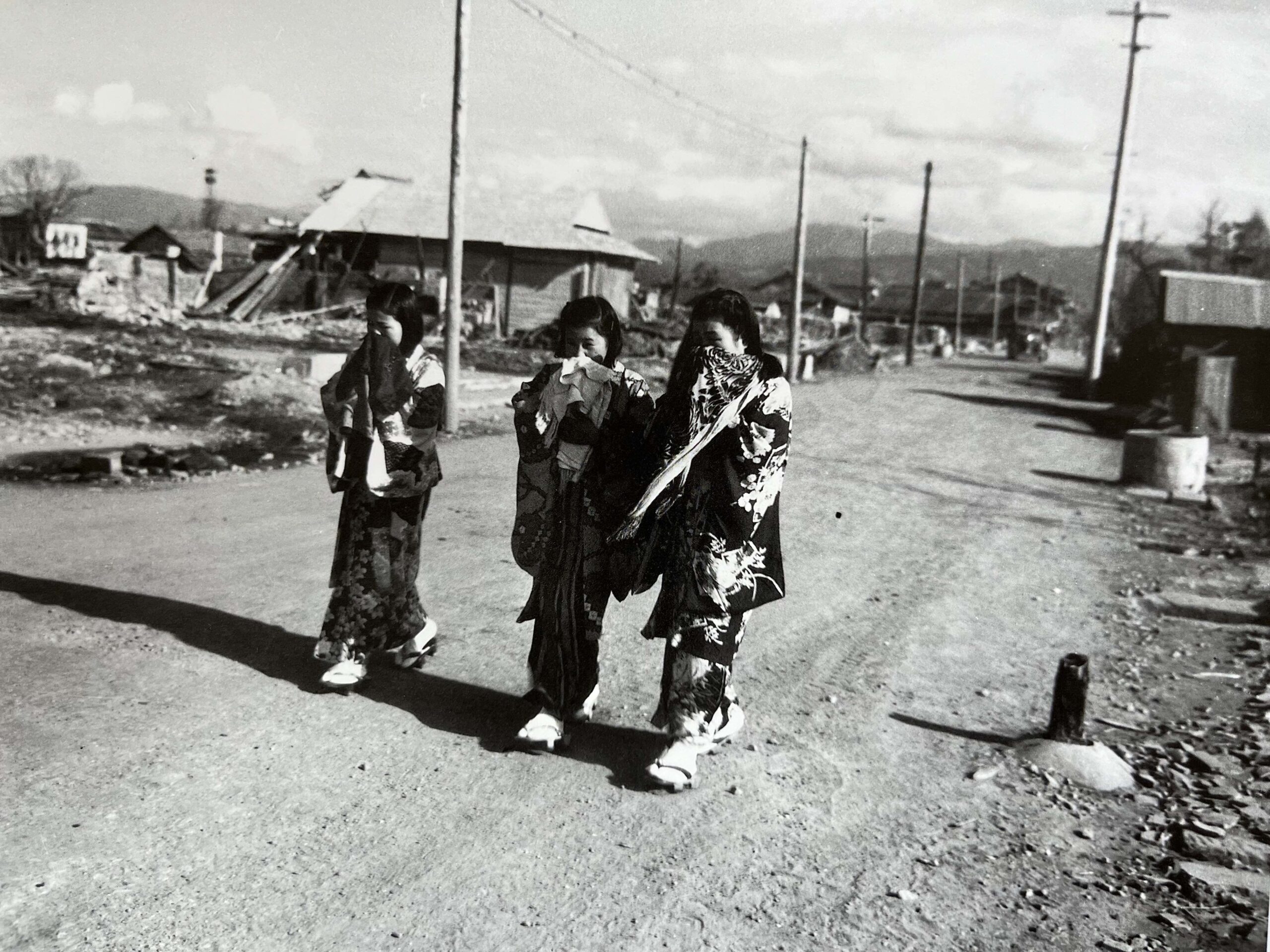

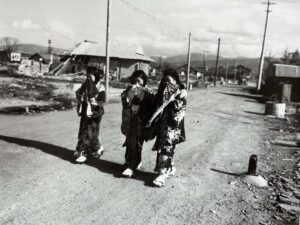

The last page in O’Donnell’s chapter on Sasebo presents a photograph of three girls walking down a dusty street (figure 6). O’Donnell zoomed out just enough to situate the girls within the destruction evident in the background. Had he used tighter cropping, the viewer would only have seen three girls dressed in kimono and not the space surrounding them. A shallow depth of field rivets the viewer’s attention on the girls, who hold their kimono sleeves against their noses in a vain attempt to ward off the stench of burning bodies emanating from nearby funeral pyres and makeshift crematoria. The girls’ shadows point to the left of the frame, leading the eye to empty lots where houses once stood. From there, the eye continues along one side of the road to take in the details in the background—more empty lots punctuated by evidence of new construction—before moving up the other side of the road to settle once again on the girls. O’Donnell’s framing and composition evoke tension and unease: the strong vertical lines of electric poles and buildings, and the elongated forms of the three girls, clash with the diagonal lines of the road and slanting shadows. Together with the slight tilt to the frame, this puts the viewer off balance. The three girls themselves create tension as well; their elegant kimono with rich floral patterns contrast with the dismal surroundings. In this photograph, O’Donnell skillfully combines form and content to convey the death and destruction that pervaded Japanese society in the early postwar.

O’Donnell moved on from Sasebo to record the devastated city of Fukuoka, where American bombers had targeted several sites: Fukuoka Harbor, a critical hub for ships traveling between Japan and Korea; the Najima Steam Power Plant, which supplied power to the Omuta and Nagasaki-Sasebo regions as well as to factories in Fukuoka; the Fukuoka Air Station, a naval air training station and a key link to the air defense of the city; and various industrial sites such as the Showa Iron Works, the Saitozaki Petroleum Center, and the Nippon Rubber Company (Japanese Air Target Analyses). On 19 June 1945, over 200 B-29 Bombers dropped over 1,500 tons of incendiary bombs on these and other sites (5th Peace Memorial Exhibition), destroying twenty-one percent of the city (Craven and Cate: 674).

The scars of war are not as visually obvious in O’Donnell’s chapter on Fukuoka. Yet, he provides subtle hints in the photographs, as well as his commentary, that convey the physical and emotional hardships that the locals faced there as a result of the war. In commentary attached to two pictures of an athletic day at an elementary school, O’Donnell observed that most of the spectators were women, children, and the elderly. Very few among the crowd were men, presumably because they had perished in the war. In another photo, O’Donnell provides a portrait of a man posing in the street wearing a heavy, Western-style winter coat and geta sandals. The man’s stoic features and dress convey a sophisticated aura, but O’Donnell’s caption reveals the heartache that must lay beneath: he lost his entire family and most of his friends in the atomic bombings. “You tell your people what it was like after the bomb,” he asked of O’Donnell, who would be haunted by these words for several months afterwards (O’Donnell 2005: 35).

Importantly, too, O’Donnell’s photos in this chapter evidence his deepening curiosity with and connection to the Japanese people and culture. He captured geisha performing traditional dances, children at work clearing roads (figure 7) or playing in neighborhood streets, firemen razing buildings damaged by the bombings, and a long line of people waiting to receive a ration of one loaf of bread. Several photos record O’Donnell as well, marking him again as a photographed subject in his documentation of Japan. O’Donnell’s repeated inclusion of photos of himself interacting with Japanese citizens captures another layer in his personal journey from hatred of a former enemy to empathy for a defeated people suffering hardship.

One sequence of photographs in the Fukuoka chapter shows O’Donnell sharing a meal with fellow Occupation servicemen and a group of Japanese (figure 8). This is followed by a picture of him and two Americans soaking in a Japanese-style bath, and then one of himself robed in a fresh yukata and linked arm-in-arm with his friends and hosts. In the first photo, O’Donnell and two young American men sit with a group of Japanese men and women. More so than the picture itself, what is striking about this page is the caption, wherein O’Donnell relates a conversation he had had in a different encounter. During a dinner with the mayor of Fukuoka, O’Donnell asked if the man’s wife had prepared the meal and if he could thank her. The Japanese mayor responded that American bombs had killed his wife the month prior. Dumbfounded by his response, O’Donnell apologized immediately, and after the dinner ran to find refuge in his tent. While we never learn more about the dinner—and might wonder whether the mayor was pressured to host the American guests or, conversely, orchestrated an opportunity for reconciliation—we do know that the occasion left a strong impression on O’Donnell. Experiences like these quite clearly prompted the shift in O’Donnell’s growing sympathy for the people he met in the ruins.

While O’Donnell experienced a conversion from hatred to reconciliation and compassion, the American media tended to convey lingering animosities for several years after Japan’s surrender. One article asserted that the Japanese would surely continue to hate Americans “very deeply for many years because of their sons and fathers killed in battle and the cities laid waste by the new atomic bomb” (Mydans 1945). In an article in Life concerning the initial moments of the American-led Occupation, one photo accentuated the antagonism that the Japanese allegedly harbored toward the Allied forces occupying their nation. The photograph shows Japanese men, women and children lined up on the side of the street. Many people shield themselves from the harsh summer sun with parasols or rags draped over their heads, and some of the men still wear military uniforms. A tire and part of a vehicle’s hood in the bottom right of the frame suggest that the photographer snapped the photo from a jeep as it drove down the city street. Underneath the photo, the caption reads:

Hostile silence greeted Americans at first. Later, strict discipline broke. Says Correspondent White, “The initial hostility was gone—it was there, we knew, underneath. The Japanese would accept us and the sulkiness would fade from their eyes in time; but the sulkiness in their hearts we would have to reckon with for years” (“U.S Occupies Japan” 1945).

While the American media often alluded to the hostility that the Occupiers sensed beneath the surface, it sometimes went so far as to describe the Japanese populace as mentally ill. Because the Japanese remained “psychologically undefeated,” one author wrote, they would either wage war again soon or else become a “nation of true neurotics and lose all value to the human race” (“The Meaning of Victory” 1945: 34). Yet another article described the Japanese as “extremely emotional” and “kept by his own ancient social system in a precarious balance between hysteria and complete submission.” Asserting that defeat in the war had produced extreme emotional stress, the author opined that the Japanese might be pushed to the breaking point until they became inured to all “civilized human teachings” (Mydans: 26). Descriptions such as these, portraying the Japanese people as “lesser men” and “mad men,” perpetuated the wartime stereotypes that had fueled the brutal fighting in the Pacific.12

In contrast to the mainstream American media, O’Donnell’s photographs in Japan 1945 lacked any hint of lingering wartime animosities or portrayals of Japanese as hostile or mentally ill. In one photo, O’Donnell himself converses with a former kamikaze pilot instructor whose nineteen-year-old brother died in a suicide mission only days before Japan’s surrender (figure 19). O’Donnell and the pilot appear at ease talking with one another. They stand next to the instructor’s plane, which bears the image of a Japanese airplane attacking an American warship. One of the most intimate instances of cross-cultural exchange O’Donnell captured featured only inanimate objects: scuffed and muddy shoes lined up neatly in the genkan (entryway, where shoes are removed) of a local church. Rugged military boots have been placed side-by-side with Japanese-style shoes and geta sandals. “In a house of worship,” O’Donnell wrote in the caption, “the two sides of the war finally come together in peace” (O’Donnell 2005: 29). By this time, it would seem, O’Donnell had renounced entirely the bitter hatred he had once felt for the Japanese.

Following the Fukuoka chapter, one on Hiroshima presents the viewer with the first scenes of nuclear destruction. The atomic bomb that fell on 6 August 1945 is arguably the most notorious bombing campaign of World War Two. The United States Strategic Bombing Survey estimated the death toll at between 70,000 and 80,000, but numbers range as high as 140,000 (Wellerstein 2020). The heat from the blast was so intense that it melted the skin off human bodies and seared their figures into blackened shadows on the sides of buildings or sidewalks. Those who survived found little relief from their injuries. One sixteen-year-old boy, four miles from the hypocenter at the time of the explosion, remained hospitalized for his burns until March of 1949 (Hideji 1978: 117). When O’Donnell visited a local hospital, another man begged the Marine to kill him and thus end his suffering (O’Donnell 1995: 86). Many victims of the atomic blast eventually recovered from their wounds, only to face a lifetime of discrimination and social stigmatization as hibakusha.

The first picture in the Hiroshima chapter depicts a cannon set up on a beach—or at least what appears to be a cannon. O’Donnell’s caption reveals the truth: it is an electric light pole mounted on concrete blocks and wooden boxes, obviously meant to trick invading Allied forces. The photos that follow this include two aerial views of the city, and then finally a photograph of O’Donnell astride his horse (figure 1). Unlike the photographs included in U.S. bombing surveys that erase the human presence, O’Donnell’s shots from above capture residents walking down rubble-lined streets. In one of the photos, a road cuts diagonally through the ruins, running below the charred remains of a church placed slightly off-center within the frame. The hard, geometric lines of the church, together with the diagonal line of the road and harsh shadows lurching across the landscape, combine to give the photograph an emotional register saturated with a chilling aura of unease. This sentiment is deepened by the mess of debris radiating away from the walls, completely engulfing the lone figure walking down the middle of the road, his shadow trailing behind. O’Donnell’s inclusion of this one person in the frame is perhaps enough to shift the viewer’s awareness from the destructive power of the U.S. military—a notion usually evoked by such aerial views—to the plight of the Japanese left to deal with their ravaged homeland.

O’Donnell’s narrative reaches a crescendo in the final chapter, assaulting the viewer with an unrelenting sequence of images of irradiated wasteland. The U.S. dropped the second atomic bomb on Nagasaki on 9 August 1945, killing between 40,000 and 70,000 people. In O’Donnell’s photos, aerial views reveal the extent of the damage, while photos that he took on the ground place the viewer smack in the middle of the destruction. A few pages into the chapter, the viewer sees the landscape of Nagasaki up close (figure 11). One photograph focuses on a sign emblazoned with the words “ATOMIC-FIELD” posted amidst a landscape of shattered roof tiles, scorched wood, and crumbling concrete. Three Japanese civilians stand in the background on the right, almost lost among the sprawling detritus. They appear minuscule compared to their surroundings, impressing on the viewer the scale of devastation.

Images of wretchedness and pain confront the viewer throughout the chapter. One photo shows a man sitting in front of a makeshift hospital. The man’s burned, disfigured face and pile of ragged clothing makes it difficult for the eye to find any singular focal point. His face is cast in shadow by a nearly unrecognizable military cap, and filthy rags cover the rest of his body, torn in places to reveal the blistered flesh underneath. Hunched forward, the man’s slumped shoulders match his facial expression in emitting a sense of utter defeat, exhaustion, and agony. Close cropping and contrasting tonal values keep the viewer’s gaze riveted on the man as the central subject, forcing the viewer to take in the details—from the burns on his face to the dirt underneath his fingernails. This photograph highlights not only the unimaginable pain of burn victims, but the lack of resources available to treat their wounds. In the caption, O’Donnell recalls that he entered the hospital seeking medical treatment for the man but was told that they had already administered mercurochrome and could do nothing more. The man’s only remaining option for relief was the standard home remedy for burns: cucumber slices.13

O’Donnell only reluctantly turned his camera on those with severe physical wounds. In one photo that conveys in no uncertain terms the unimaginable physical suffering that he witnessed, O’Donnell captured a close-up of a boy’s back, his burned flesh filled with maggots and oozing sores. In the caption, O’Donnell remembered the sickening smell as he helped to clear the maggots from the wounds. Horrified at the scene, O’Donnell vowed to never again photograph burn victims unless he received orders to do so. Even so, death and human suffering dominate the chapter on Nagasaki. One particularly heart-wrenching photograph shows a young boy standing at attention, his younger sibling strapped to his back (figure 12). At first glance, it appears that the toddler is merely sleeping. O’Donnell thought just this when he first spotted the pair, believing that the babe was snuggled safely on the back of his older brother. Soon, however, O’Donnell discovered the truth:

The men in white masks walked over to him [the child] and quietly began to take off the rope that was holding the baby. That is when I saw that the baby was already dead. The men held the body by the hands and feet and placed it on the fire. The boy stood there straight without moving, watching the flames. He was biting his lower lip so hard that it shone with blood. The flame burned low like the sun going down. The boy turned around and walked silently away (Quoted in Nolan 2020).

Other pictures in the chapter depict the Japanese, especially children, as they continued to live among the atomic ruins. In one photo, a young boy pushing two toddlers in a wooden cart has paused to look at the Marine in trepidation. After taking the photo, O’Donnell extended a sign of friendship by giving the older boy an apple. The boy took one bite, then passed it to the two younger children in his care. O’Donnell watched flies cover the apple and buzz in and out of the children’s mouths as they shared the apple in silence. A second photo shows a girl posing in a kimono—the elaborate clothing providing a sharp contrast to the scorched landscape extending out behind her (figure 13). In the caption, O’Donnell explains that the girl lost her hearing because of the American bombs. Yet another photograph brings the viewer inside the space of an elementary school classroom. The desks are neat and straight, the floor clean and the children all sit, erect in their posture, with attention pinned to the teacher at the front of the classroom. Through the windows in the background, the viewer gets a glimpse of a ruined landscape dotted with charred buildings and barren trees rising out of the ground, black and twisted. In another photo, O’Donnell snapped a group of repatriated soldiers recently returned to Japan marching in a line under the supervision of American GIs. The veterans trail behind a horse-drawn cart laden with their possessions, and one man pedals alongside the cart on a bicycle. The photo shows, in plain terms, a defeated and demoralized army coming home to a city devastated by war.

The chapter ends with a series of photographs of churches, bringing the reader full circle to the religious imagery that opened the book. However, these dark, haunting photographs are the antithesis of the American priest in his white robes surrounded by U.S. Marines that opened the book (figure 4). One photo of the Urakami Cathedral shows the church sitting on a hill in the background, an expanse of debris extending between the viewer and the church (figure 14). Ominous clouds push down on the cathedral from above, casting it and the surrounding landscape in sombre shadows. Two Japanese citizens stand under the eaves of a shack in the middle of the frame, their forms nearly invisible in the ravaged landscape. Religious imagery saturates the first and last photographs in the book. But whereas the first few photographs are filled with light—perhaps indicative of the belief in the just cause of the Occupation to reform a wartime enemy—the final photographs are so dark that they verge on the apocalyptic, reflecting O’Donnell’s own horror at what he witnessed in Japan.

Looking at the Ruins of War

When Revered Richard Lewis Lammers, Director of the Good Neighbor Christian Center in Morioka, saw O’Donnell’s photos on display at the Brookmeade Congregational Church in Nashville in 1991, he insisted that they be exhibited in Japan because “we’ve not seen pictures like that of what really happened in Hiroshima and Nagasaki” (O’Donnell 2005). And so, the photos were put on display in Morioka, Aomori, Hirosaki, Akita, and Shinjo, and later traveled to Tokyo and other larger cities. O’Donnell and those involved in hosting the exhibits felt that the photo displays were a sort of “healing ministry,” in part because the photos articulated the experiences of those who had survived the bombings as well as those who had suffered from radiation exposure (ibid.).

While Lammers stressed the importance of looking at war in all its horrors, many have argued that looking at war photography, ranging from the destruction of the built environment to the mutilation of human bodies and everything in between, runs the risk of desensitizing viewers to the profound atrocities of war.14 To be sure, O’Donnell’s photos centralize the human and environmental toll exacted by war. However, rather than reducing the Japanese populace to mere victims, his probing lens adeptly captured the humanity of the Japanese within, and in spaces beyond, the ruins. The result is a series of poignant photographs that give the subjects agency beyond the confines of war, defeat, and Occupation, all by allowing viewers a glimpse into their daily lives. This “space of relations” between the viewer and the photographed subjects, as photography scholar Ariella Azoulay has called it, further demonstrates the interplay between space and meaning so important to understanding O’Donnell’s photos (Azoulay 2008: 376).

As O’Donnell stated, his photos have become important objects that have brought healing from war to many people. What these photographs cannot do, however, is prevent future wars. If photographs possessed this power, humans would have ceased waging war when the first photographs of war were taken in 1847 (O’Hearn 2016). Even if the production and circulation of photographs of war could curtail conflict, we must remember that we are looking at people in their most vulnerable moments, who often have no say in how photographs of their personal trauma are shared and used. Even though O’Donnell felt compelled “to tell the story of what lay beneath the mushroom cloud, always left untold,” he himself at times engaged in a deliberate act of not looking as he moved through ravaged spaces and encountered ravaged bodies (O’Donnell 1995: 115). In doing so, O’Donnell addressed the power of the U.S. as a military and occupying authority, but he also negotiated with that power by shifting visual focus from war ravaged bodies to citizens rebuilding their lives (Azoulay 2008: 24). This, I believe, is why it is important to examine and re-examine O’Donnell’s photographs. These scenes of normalcy, even though set against a backdrop of ruin—or perhaps because of it—opened space for the Japanese to become more than a defeated and occupied nation in the eyes of O’Donnell and his viewers. They become what they had always been: fellow humans.

Bibliography

Ahara, Hideji. 1978. Hiroshima-Nagasaki: A Pictorial Record of the Atomic Destruction. Tokyo: Hiroshima-Nagasaki Publishing Committee.

Air Objective Folder Fukuoka Region, records of the United States Strategic Bombing Survey (Pacific). Japanese Air Target Analyses, 1942–45 (NARA M1653).

Braw, Monica. 1991. The Atomic Bomb Suppressed: American Censorship in Occupied Japan. New York: M.E. Sharpe, Inc.

Brodie, Janet Farrell. 2015. “Radiation Secrecy and Censorship after Hiroshima and Nagasaki.” Journal of Social History 48(4): 842–86.

Conner, Ken, Debra Heimerdinger, and Horace Bristol. 1996. Horace Bristol: An American View. San Francisco: Chronicle Books.

“Controversy over the Enola Gay Exhibition.” 2016. Atomic Heritage Foundation, 17 October. https://ahf.nuclearmuseum.org/ahf/history/controversy-over-enola-gay-exhibition/.

Cosgrove, Ben. “Hiroshima and Nagasaki: Photos from the Ruins, 1945.” Life. https://www.life.com/history/hiroshima-and-nagasaki-photos-from-the-ruins/.

Craven, Wesley Frank and James Lea Cate. 1953. The Army Air Forces in World War II. Volume Five. The Pacific: Matterhorn to Nagasaki, June 1944 to August 1945. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Crockett, Lucy Herndon. 1949. Popcorn on the Ginza: An Informal Portrait of Postwar Japan. London: Victor Gollancz.

Dower, John. 1986. War without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War. New York: Pantheon Books.

Fainsod, Merle. 1946. “Military Government and the Occupation of Japan.” In D. G. Haring (ed.) Japan’s Prospect (pp. 287–304). Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard University Press.

Gordon, Andrew. 2013. A Modern History of Japan: From Tokugawa Times to the Present, third edition. New York: Oxford University Press.

Graulich, Heather. 2007. “A Photographer’s Legacy Tarnished,” National Press Photographer’s Association, 15 September. https://nppa.org/news/1618.

Harvey, Justin., Charlie Daniels, Matthew Emigh, and Kevin Crane. 2007. “Joe O’Donnell ‘Snapshot.’” Nashville WWII Stories. Nashville Public Television. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gGc1-vSQMHM.

Hatsuda, Kōsei. 2002. “Tokyo’s Black Markets as an Alternative Urban Space: Occupation, Violence, and Disaster Reconstruction.” Journal of Urban History 48(5): 1046–1065.

Hein, Laura. 2018. Post-Fascist Japan: Political Culture in Kamakura after the Second World War. New York: Bloomsbury Academic Press.

Jacobs, Robert. 2010. “Reconstructing the Perpetrator’s Soul by Reconstructing the Victim’s Body: The Portrayal of the ‘Hiroshima Maidens’ by the Mainstream Media in the United States.” Intersections: Gender and Sexuality in Asia and the Pacific 24. http://intersections.anu.edu.au/issue24/jacobs.htm.

Jung, Ji Hee. 2018. “Seductive Alienation: The American Way of Life Rearticulated in Occupied Japan.” Asian Studies Review 42(3): 498–516.

Kerr, Bartlett E. 1991. Flames over Tokyo: The U.S. Army Air Forces’ Incendiary Campaign Against Japan, 1944–1945. New York: D.I. Fine.

Kitamura, Hiroshi. 2012. “America’s Racial Limits: U.S. Cinema and the Occupation of Japan.”The Japanese Journal of American Studies 23: 139–162.

Koikari, Mire. 2009. Pedagogy of Democracy: Feminism and the Cold War in the U.S. Occupation of Japan. Temple University Press.

Low, Morris. 2015. “American Photography during the Allied Occupation of Japan: The Work of John W. Bennett.” History of Photography, 39(3): 263–278.

Martin, Douglas. 2007. “Joe O’Donnell, 85, Dies; Long a Leading Photographer,” The New York Times, 14 August. https://www.nytimes.com/2007/08/14/washington/14odonnell.html.

“Medical Report of the Atomic Bombing in Hiroshima,” Army Medical College, First Tokyo Army Hospital via joint medical commission for investigation of effects of atomic bombs. Report No. 3c(25), USSBS Index Section 2.

Miles, Melissa and Robin Gerster. 2018. Pacific Exposures: Photography and the Australia-Japan Relationship. Australian National University Press.

Mitchell, Greg. 2005. “Hiroshima Film Cover-up Exposed. Censored 1945 Footage to Air.” The Asia-Pacific Journal 3(8): https://apjjf.org/-Greg-Mitchell/1554/article.html.

Mydans, Shelly. 1945. “The Japanese Mind in Defeat,” Life, 3 September. “Myths and Realities About Incendiary Weapons.” 2018. Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/news/2018/11/14/myths-and-realities-about-incendiary-weapons.

Nayar, Pramod K. 2023. Nuclear Cultures: Irradiated Subjects, Aesthetics and Planetary Precarity. New York: Routledge.

Nolan, James L. 2020. Atomic Doctors: An Unflinching Examination of the Moral and Professional Dilemmas Faced by Physicians who took Part in the Manhattan Project. Harvard: Harvard University Press.

“Nuclear.” Nuclear Threat Initiative. https://www.nti.org/area/nuclear/.

Ochi, Hiromi. 2006. “What Did She Read?: The Cultural Occupation of Post-War Japan and Translated Girls’ Literature.” F-GENS Jānaru: Frontiers of Gender Studies 5: 359–363.

O’Donnell, Joe. 2005. “A Straight Path Through Hell.” American Heritage 56(3). https://www.americanheritage.com/straight-path-through-hell.

______. 2005. Japan 1945: A U.S. Marine’s Photographs from Ground Zero, first edition. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press.

O’Donnell, Joe and Jennifer Alldredge. 1995. トランクの中の日本:米従軍カメラマンの非公式記録 [Images from the Trunk]. Tokyo: Shōgakukan.

O’Donnell, Tyge. 2011. “Interview with David Weir about Photographer Joe O’Donnell.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4tu_uxqwYoo.

Richardson, Jack. 2006. “Seeing, Thinking, Mapping, Moving: Considerations of Space in Visual Culture.” Visual Arts Research 32(2): 62–68.

“Sasebo History: Assorted Data on a Historical City in Southern Japan.” Center for Research: Allied POWS Under the Japanese. http://www.mansell.com/pow_resources/camplists/fukuoka/fuku_18_sasebo/sasebo_history/sasebo_history.html.

Sasebo Report No. 3-a(37). USSBS Index Section 7. Records of the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey; Entry 59, Security-Classified Damage Assessment Reports, 1945. https://dl.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/3984539.

Schultz, Joan M. 2011. “Felix Man’s ‘Canada’: Imagined Geographies and Pre-Texts of Looking.” In Payne, Carol and Andrea Kunard. (Eds.). The Culture Work of Photography in Canada. London: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Selden, Mark. 2007. “A Forgotten Holocaust: US Bombing Strategy, the Destruction of Japanese Cities & the American Way of War from World War II to Iraq.” The Asia-Pacific Journal 5(5): https://apjjf.org/-Mark-Selden/2414/article.html.

______. 2005. “Foreword. After the Bomb: Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and the Photographic Record.” In Japan 1945: A U.S. Marine’s Photographs from Ground Zero, first edition. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press.

Senate Resolution 257: “Relating to the ‘Enola Gay’ Exhibit.” Congressional Record Volume 140, Number 131. Monday, 19 September, 1994. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CREC-1994-09-19/html/CREC-1994-09-19-pt1-PgS48.htm.

Shibusawa, Naoko. 2006. America’s Geisha Ally: Reimagining the Japanese Enemy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

「占領軍ルックからスラックスへ」[From the Occupier’s Looks to Slacks]. 1977. In 占領したの日本 [Japan Under Occupation]. Volume 9 of 昭和日本史 [Showa Japanese History] (pp. 47–48). Tokyo: Akatsuki Kyōiku Tosho.

Smylitopoulos, Christina. (Ed.). 2016. Agents of Space: Eighteenth-Century Art, Architecture, and Visual Culture. Newcastle upon Tyne, Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Sontag, Susan. 2002. “Looking at War.” The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2002/12/09/looking-at-war.

______. 1977. On Photography. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Spector, Ronald. 1985. Eagle Against the Sun: The American War with Japan. New York: Vintage Books.

Takemae, Eiji. 2003. The Allied Occupation of Japan, translated by Robert Ricketts and Sebastian Swann. New York: Continuum.

Taylor, N.A.J., and Robert Jacobs. (Eds.). 2018. Reimagining Hiroshima and Nagasaki: Nuclear Humanities in the Post-Cold War. New York: Routledge.

Thwaites, Lily. 2019. “The morality of war photography.” The Boer. https://theboar.org/2019/11/war-photography/.

“The Meaning of Victory.” 1945. Life. 27 August.

“The Tokyo Express. A Life Photographer Takes a Ride to Hiroshima on Japan’s Best Train.” 1945. Life. 8 October.

Tsuchiya, Yuka. 2002. “Imagined America in Occupied Japan: (Re-)Educational Films Shown by the U.S. Occupation Forces to the Japanese, 1948–1952. The Japanese Journal of American Studies 13: 193-213.

“U.S. Occupies Japan.” 1945. Life. 10 September. Photos by Bernard Hoffman, Carl Mydans, and George Silk.

“War’s Ending.” 1945. Life. 20 August.

Wellerstein, Alex. “Counting the Dead at Hiroshima and Nagasaki.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists: 75 Years and Counting. https://thebulletin.org/2020/08/counting-the-dead-at- hiroshima-and-nagasaki/.

“5th Peace Memorial Exhibition ‘Fukuoka Air Raid.’” Fukuoka Now. http://www.fukuoka-now.com/en/event/5th-peace-memorial-exhibition-fukuoka-air-raid/.

- As John Dower explains, the racial hatreds on both sides led to unimaginable atrocities. The Allies emphasized the subhuman nature of the Japanese, portraying them as inherently inferior (apes, vermin, and children), while the Japanese affirmed their purity by casting the West as monsters, devils, and demons (Dower 1986).

- O’Donnell bought the horse in Nagasaki with 20 packs of cigarettes (“A Straight Path Through Hell” 2005).

- The Public Welfare Weekly Report for 1946, for example, records gathering over 100 children and taking them to orphanages on a near-weekly basis. In 1948 there was an estimated 120,000 homeless children, including 30,000 war orphans (“Occupier’s Looks” 1977: 47–48, 101).

- For example, see Ochi, Jung, Tsuchiya.

- The Japanese photographer claimed that the U.S. military took “every record [he] made” of the Nagasaki bombing.

- O’Donnell befriended a boy who cared for his horse when he was unable to travel with it. Tragically, the boy died from an infection in the leg he had lost during the war. The boy’s relatives invited O’Donnell into their home to partake in a memorial for him. At the conclusion of the memorial, the boy’s grandmother gave O’Donnell the boy’s crutch as a symbol of their friendship (“A Straight Path Through Hell”).

- For an explanation of hibakusha and their portrayal in American media, see Jacobs.

- This article focuses on the Vanderbilt edition, as it contains additional photos.

- See “The Effects of the Atomic Bombings on Hiroshima and Nagasaki,” “Effects of the Atomic Bomb on Hiroshima, Japan,” and “Effects of the Atomic Bomb on Nagasaki, Japan.”

- For more on the censorship of reports on the atomic bombings, see Brodie, Mitchell.

- The Doolittle Raid was the first air raid against Japan on 18 April 1942. Due to a picket boat line set up several hundred miles east of Japan by Admiral Yamamoto, the sixteen B-25 bombers had to launch over 650 miles from Japan. Because of the long distance they had to travel, the pilots were forced to strike Tokyo in the daylight and land in China. Although damage in Tokyo was minimal, the raid had a tremendous psychological impact on Japan (Spector 1985: 154–155).

- However, as John Dower explains, such wartime rhetoric was flipped on its head following an end to the war, thereby fostering the development of peaceful relations between the two countries. In his analysis, the U.S. saw itself as becoming a parent to the childlike Japanese, and a therapist to the madmen (Dower 1986: 293–317).

- For others, even those with burns that exposed bone, the only supplies available were tincture-soaked gauze (Ahara 1978: 102). Of those who survived the initial blast, countless died from their injuries, as well as from radiation poisoning. In the subsequent weeks and months, first funeral pyres, and then graves and memorial sites, sprawled across Nagasaki.

- Susan Sontag cogently argued this position in her seminal work On Photography (1977). However, she later grapples with the argument that repeated exposure to atrocity decreases sympathy in her essay “Looking at War” (2002).