Abstract: Why do we give to distant sufferers in need? Are we motivated primarily by altruism or opportunism? What, if anything, do givers expect in return for significant acts of generosity? This article explores these questions through an examination of corporate giving to Japan from America’s industrial heartland following the Great Kantō Earthquake. Large corporate donations comprised a significant part of America’s “tsunami of aid” to Japan in 1923. Why? What did corporate givers hope to accomplish or achieve? Recognition of Japan as an important commercial partner and expectations of expanded trade, my findings suggest, significantly influenced donations from key corporate actors.

Keywords: American humanitarianism abroad, post-disaster corporate giving, Japanese-American relations, American Red Cross, 1920s globalism

Mixed emotions ran through America’s industrial heartland in September 1923. On one hand, residents from Gary, Indiana, to Buffalo, New York, gasped in horror as news of Japan’s earthquake tragedy unfolded. 250,000 had perished in Tokyo and Yokohama alone, the Buffalo Enquirer and Detroit Free Press reported, with many more deaths likely in cities across Japan’s main island (Buffalo Enquirer 1923; Detroit Free Press 1923). “500,000 May be the Toll of Jap Cataclysm,” projected a bold headline in the Hammond Times of Northwest Indiana (Hammond Lake Country Times 1923). Beyond accepting that Japan’s earthquake had led to unprecedented deaths, others came to believe that large swaths of urban Japan had been annihilated. Earthquakes, fires, and tsunami, the Cleveland Plain Dealer reported, had left behind nothing but desolation. “Tokyo,” its pages informed readers, was “one vast city of misery” (Cleveland Plain Dealer 1923). Japan had been “stricken” the New York World informed its readers, and its survivors were stalked by the ominous spectre of death.

Figure 1: Japan under the spectre of death (New York World 1923, 4).

At the same time, a sense of opportunity permeated the region, if not all of America. Japan would be rebuilt and America could provide all of the material resources necessary for this herculean task. “Japan,” the Wall Street Journal suggested just four days after the calamity, “will need a large tonnage of steel for rebuilding and the lion’s share of this tonnage should come to mills here” (Wall Street Journal 1923b). Japanese steel mills, they added, could only provide roughly fifty percent of Japan’s ordinary steel requirements and reconstructing Tokyo and Yokohama would be anything but a normal situation. John W. Hill, Financial Editor of the Iron Trade Review informed the Buffalo Commercial broadsheet that Japanese demand for reconstruction materials would be “incalculable” (Buffalo Commercial 1923). “Her catastrophe,” the Baltimore Sun proclaimed with no sense of shame, “is our opportunity” (Baltimore Sun 1923). Japan, as a line drawing entitled “Emerging” published in the St Louis Star and Times suggested, would rise again. It would do so with the assistance of America.

Figure 2: The Rising Sun Rises Again (St Louis Star and Times 1923, 16).

Almost as soon as Americans learned of Japan’s disaster, they were asked to assist sufferers through donations to the American Red Cross (ARC). People from all regions and all classes responded. They gave like they never had before, and haven’t ever since. When donations made to the American Red Cross (ARC) from private citizens and businesses are counted alongside supplies donated and transported by US army and navy units based in the Philippines, aid from Japanese American communities, corporations that gave directly to Japan, and people who donated to organizations outside the ARC, the total value of support approached $USD 25 million. This was no small amount. The monetary value of aid given to Japan in 1923, when measured as a percentage of US gross domestic product (GDP), remains unrivaled to this day. Americans have never given more, as a percentage of GDP in aid, following an overseas natural disaster, than they did after the Great Kantō Earthquake. In fact, as a percentage of GDP, America gave more aid to Japan in 1923 than they did to all nations affected by the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami combined (Schencking 2019). Why?

American political elites, commentators, and diplomats in Japan declared that aid was motivated by “altruistic” aims. Proof of this, they asserted, was the fact America afforded Japan complete control over all donated food, money, and supplies—a privilege never before granted to overseas relief recipients. American officials even supported Japan’s decision to sell donated relief supplies to sufferers (United States Department of State n.d.). They likewise refused to object to or even criticize Japan’s decision to sell donated but unneeded, flour and wheat to overseas buyers: a similar act had sabotaged the American Relief Administration’s humanitarian campaign in the USSR just months earlier (Patenaude 2002). American officials, in fact, repeatedly informed their Japanese counterparts that aid was given with no strings attached. But was it? Don’t givers always expect something in return for significant acts of generosity?

Unfortunately, we still know comparatively little about how members of the international community viewed, interpreted, or responded to this catastrophe. Historians of American humanitarianism abroad have given only cursory attention to aid and assistance given to Japan in 1923 (Curti 1963; Ekbladh 2009; McCleary 2009; Irwin 2013; Cabanes 2014; Cullather 2015; Watenpaugh 2015). One recent publication has shown that many Americans had been motivated to give to Japan in part out of a belief that humanitarianism would advance amity and result in long-lasting peace between both nations (Schencking 2021). Other factors, economic in nature, may also have encouraged Americans to give. If so, did such giving likewise come with the expected “returns” on American generosity and did it yield positive results? What can an exploration of elite corporate giving from one section of America tell us about aims and expectations of post-disaster humanitarian giving?

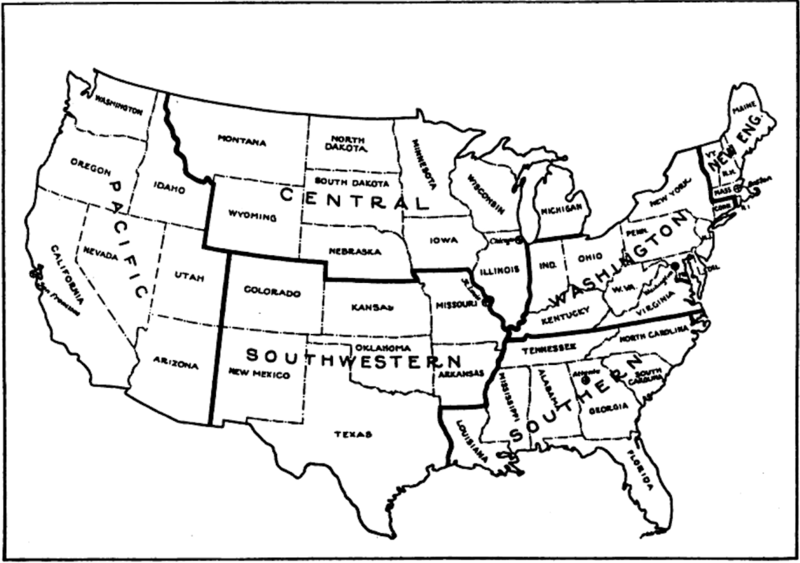

Soon after news of Japan’s tragedy reached America, President Calvin Coolidge directed the ARC to undertake a nationwide “Japan Relief” campaign. Setting an initial target at $USD 5 million, Coolidge appealed to all Americans on 4 September to assist the “friendly nation of Japan.” He informed the press that he had directed all branches of government, including the military, to “go the limit” in support (Washington Evening Star 1923; Chicago Tribune 1923). The ARC quickly established six collection divisions and set regional quotas for each (American National Red Cross n.d.).

Figure 3: American Red Cross Collection Divisions (American National Red Cross 1924, 43).

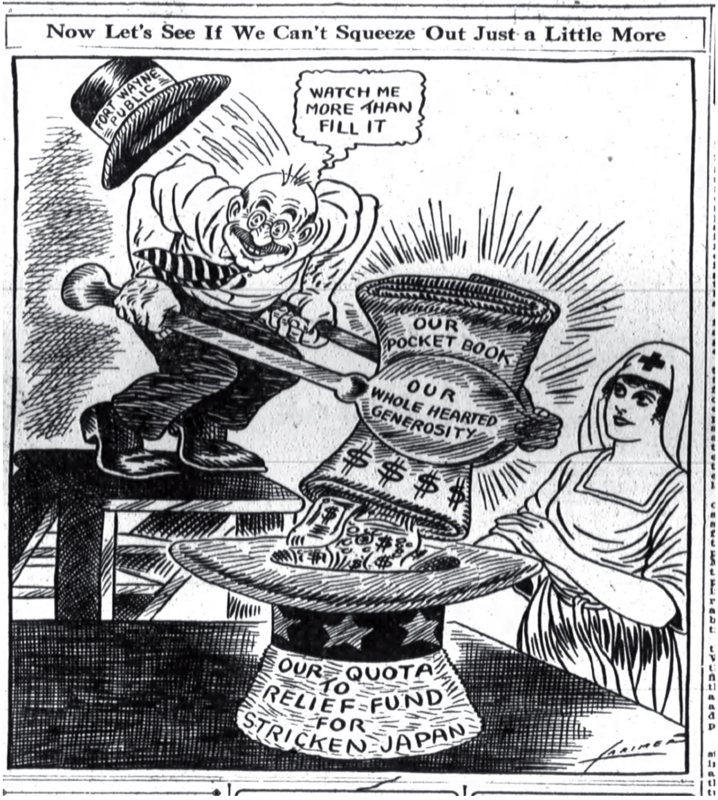

Within the six divisions, 3,600 local ARC chapters were given specific collection targets, but were afforded complete leeway over how best to reach their individual quotas. For the vast majority of Americans, giving to Japan was a distinctly “local” undertaking. By the time the ARC collection campaign concluded, Americans had donated nearly $USD 11.8 million, more than double the amount Coolidge had requested. Virtually every community had “squeezed just a little more out,” as the following line drawing published in the 13 September 1923 Fort Wayne Daily News implied.

Figure 4: Fort Wayne, Indiana Responds (Fort Wayne Daily News 1923, 4).

Collection techniques varied widely across America. In St. Louis, US postal carriers delivered, and then collected free of charge, ARC-issued donation envelopes to every resident (St. Louis Post Dispatch, 1923). In Seattle, officials organized teams of “four-minute” speakers who fanned out across the Emerald City to “tell the story of the needs of the stricken people of Japan” to aid collections (Seattle Post-Intelligencer 1923). In Honolulu, Hawaii, Radio Station KGU secured donations by conducting the territory’s first radiothon where by listeners requested music nightly between 7:30 and 9:00pm in exchange for a pledge to donate money for Japanese sufferers (Honolulu Advertiser 1923). To reach their $USD 3,000 quota, the Miami chapter of the ARC asked representatives of the Rotary, Kiwanis, Civitan, Exchange, AD, and Women’s Clubs to raise $USD 500 each among their membership ranks (Miami Herald 1923). ARC officials in Detroit, Michigan informed residents not to give to any individual asking for donations at homes, businesses, or on street corners as person-to-person solicitation would not be conducted (Detroit Free Press 1923b). Rather, the 502-member Japan Relief Committee targeted businesses directly. If Detroit industrialists needed any prodding to give, which they did not, the Detroit Free Press reminded readers in an article entitled “Tokyo to Repay Thousand Fold,” that Japan was a country worth assisting. Generosity now, they argued, would undoubtedly be rewarded with increased trade carried out, importantly, in cash (Detroit Free Press 1923c).

The ARC Washington Division included some of America’s wealthiest and most industrially consequential states, including Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania, New York, and New Jersey. It also incorporated the coal-rich state of West Virginia, the nation’s capital (the District of Columbia), Maryland, Delaware, Virginia, and Kentucky. The population of the Washington Division, some 40. 6 million, was approximately 38% of the nation’s total of 105.7 million. But, ARC officials believed its residents could give more than their national demographic footprint given the division’s wealth and the ties many leading industries based there had with Japan. Washington Division residents were therefore tasked with giving 55% of the ARC national quota of $5.25 million to Japan relief, or $2.9 million. Division residents did not disappoint. They contributed more than $6.3 million, or approximately 56% of the nation’s total as of January 1924 (American National Red Cross n.d.; United States Department of State n.d.).

A unique feature of America’s tsunami of aid to Japan in 1923, was the significant number of large corporate donations offered, particularly from businesses that operated in America’s Washington Division. Often, these large donations came from businesses that had well-established commercial relations with Japan. Aid, in this sense, was viewed by select corporate actors as a way to recognize Japan’s status as an important commercial partner. The US Silk Association, for example, which relied almost exclusively on Japan to meet America’s nearly insatiable appetite for high quality silk, collected just over $USD 400,000 for Japan—more than the ARC raised across the eight states that comprised the Southern division (New York Times 1923b; New York Times 1923c). Other large corporate entities with headquarters in the ARC Washington Division followed suit.

Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing and Westinghouse International had many reasons to assist Japan beyond humanitarian idealism. Westinghouse was one of America’s largest manufacturers and exporters of large electric products ranging from hydroelectric turbines, industrial power generators, and locomotives, to household items, such as oscillating fans and coffee percolators. Japan was one of its best international customers. From the late nineteenth century onward, Westinghouse executives had forged increasingly strong ties with many Japanese political and industrial elites (Wall Street Journal 1923e). Orders for Westinghouse products accordingly grew over time, but the firm remained in stiff competition with the General Electric Corporation and the German-based corporation, Siemens, within Japan. Just prior to the earthquake Westinghouse had beaten bids by both rivals and secured an order from the Tokyo Electric Company for materials to construct a 150,000-horsepower electricity generating plant in Tokyo. The Nagoya-based Toho Electric Company had likewise placed orders with Westinghouse for electricity generating components for a hydroelectric dam project near Fukuoka on the island of Kyushu. These large-scale projects supplemented smaller orders placed in 1923 for electric locomotives, electrical equipment, and generating supplies for use across Japan (New York Tribune 1923).

Clearly, it was in Westinghouse Electric’s corporate interests to exhibit sympathy and to support one of its best customers at a time of serious need. Westinghouse officials understood that Tokyo and Yokohama’s entire power grid, from generators and power substations, to transformers and electrical wires, had all been savaged through earthquake and fire. Virtually all components of this burgeoning network required replacing and Westinghouse hoped to be given the opportunity to meet Japan’s needs. Moreover, the destruction of electric locomotives and tramcars in the disaster zone had been nearly complete, making market opportunities for those products seem boundless. Officials desired to capitalize on this catastrophe and believed that a heartfelt show of sympathy was not only warranted, but was also an act that would not go unnoticed. Company executives subsequently announced the largest single corporate donation collected on the opening day of the New York City ARC Japan relief drive: $25,000 (New York Times 1923). This single donation was larger than what the ARC raised in the states of Vermont, Mississippi, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Wyoming, Arkansas, New Mexico, Arizona, Idaho, or Nevada individually over the duration of the collection campaign.

Understanding the importance of personal connections in Japan, Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing chairman, Guy E. Tripp, and General Electric International president, Osborne, departed for Tokyo in early October (Philadelphia Inquirer 1923). Many factors motivated their trip. First, they wished to express their personal condolences to Japanese officials. Second, Tripp and Osborne were keen to see for themselves the destruction meted out, hopping to ascertain the full scale of opportunity that existed for Westinghouse. Finally, Osborne wished to give a number of Westinghouse-made wedding presents to the Japanese Crown Prince (Buffalo Courier 1923).

Opportunism also proved a strong motivator for Tripp and Osborne. Both executives hoped to take advantage of Japan’s pressing reconstruction needs, particularly in relation to products that Westinghouse could provide, to finalize negotiations on a joint venture with Mitsubishi and their Japan based import agent, the Takata Group. If successful, Tripp and Osborne believed an agreement could offer Westinghouse an opportunity for long-term dominance in Japan and enable it to beat out its chief rivals within the expanding Japanese market.

Over the previous two years, Westinghouse executives in Tokyo and from America had engaged in lengthy negotiations with executives from Mitsubishi and Takata. Their goal was to form a large combine that would manufacture and sell Westinghouse-patented electrical goods in Japan and its colonies under license. Many of the products Westinghouse hoped to produce and sell in Japan under a joint venture, Westinghouse officials believed, would be in high demand during Japan’s reconstruction. In November 1923, all three institutions announced that they would join forces to form the Mitsubishi Electric Manufacturing Company (Chicago Tribune 1923c; Pittsburgh Post-Gazette 1923b). The agreement was a boon to Westinghouse (Nishimura 2017 pp. 36–37). Westinghouse secured roughly a 10% ownership stake in the new company and obtained “free, unrestricted, and exclusive license to manufacture, use, and sell” all Mitsubishi Electric patented products registered outside of Japan. In exchange, Westinghouse granted patent licences to Mitsubishi Electric to all of its products, excluding radio-related equipment, for manufacture and sale within Japan, its empire, and dependencies—but with the important condition that royalties would be secured with each unit produced. Finalized as Japan’s capital and most important port city lay in ruins, the agreement was a success for Westinghouse. Vice President of Westinghouse International, E.D. Kilburn, lauded the arrangement, informing journalists that it would give Westinghouse unrivalled access to Japan and enable it take a lead role assisting with not only the reconstruction of Japan, but the continued electrification of Japan’s rail network and expansion of its electricity generating capacity (Pittsburgh Daily Press 1923b; Wall Street Journal 1923f). Royalties, moreover, would provide a steady source of income in an expanding market for Westinghouse.

Many shared the belief that opportunity awaited in Japan and that acts of generosity following disaster could help secure lucrative profits for years to come. Chairman of the US Federal Reserve, Benjamin Strong, was one such individual. Financial assistance to Japan, he informed Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes, could foster a long-lasting boon to US-Japan commercial relations. Humanitarian and economic service, he asserted, “will never be forgotten by the Japanese, whose memory is oriental and almost uncanny in such matters” (United States Department of State n.d. (b)). Executives from a few key industries, moreover, believed that the post-disaster period would be one of unprecedented material rewards if reconstruction orders were placed in America. Giving to Japan at its moment of greatest need, they predicted, would result in increased trade opportunities for years to follow. “Calamities of this kind open the heart of the giver and receiver,” Charles E. Mitchell, president of National City Bank declared on the opening day of the ARC relief drive. “If the money contributed is spent in the right way,” he added, “this calamity will be a boon to existing relations between Japan and the United States” (Wall Street Journal 1923).

American Steel producers agreed wholeheartedly with Mitchell and were some of the country’s most generous donors. Notable acts of giving included: US Steel ($150,000 donation to the ARC; $15,000 to the New York Japan Society List), US Steel Products ($5,000), Youngstown Iron Sheet and Tube Company ($25,000), Homestead Steel ($25,000), Bethlehem Steel ($25,000), and the Railway Steel Spring Company ($5,000). As with Westinghouse, steel producers had found a new and important market in Japan from the time of the First World War onward. Iron Age editors claimed that Japan had kept America’s steel exports from falling to “pitiful figures” after the war concluded (Iron Age 1923c; Wall Street Journal 1923d). This was not hyperbole. Between 1919 and 1923, only Canada imported more steel from the United States than Japan.

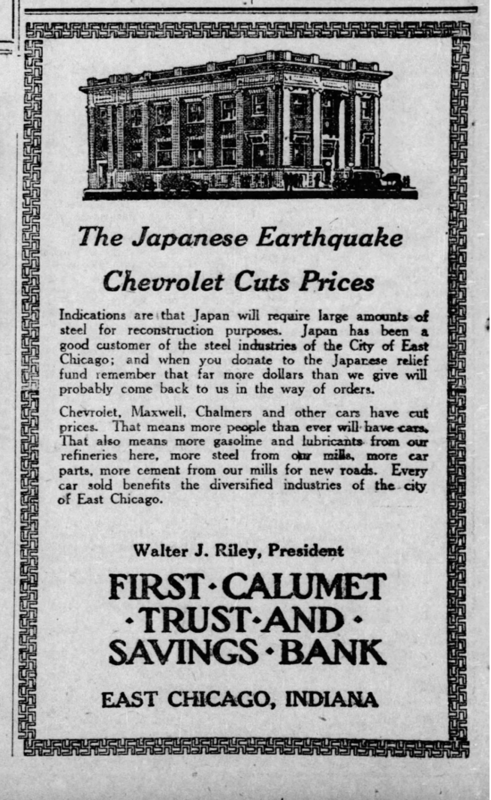

Not surprisingly, America’s steel producing and exporting regions buzzed with excitement at the prospect of future orders from Japan. Giving now, many commentators asserted, could reap huge windfalls for years to come. Midwestern newspapers suggested that Gary, Indiana, mills would be utilized for roughly half of Japan’s reconstruction steel requirements (Indianapolis Star 1923). The Muncie Star Press suggested $100 million worth of steel would be needed to rebuild Japan’s “cities, bridges, and railroads”(Muncie Star Press 1923). Steel representatives in Pittsburgh claimed “an enormous tonnage of tin plate and corrugated sheets” would be required for temporary housing, while a Youngstown, Ohio, steel executive stated that demand for sheets, plates, pipes, and wire nails for temporary reconstruction would be sizeable (Wall Street Journal 1923c). “Japan has been a good customer of the steel industries of East Chicago,” a large advertisement announced in the 7 September Hammond Lake County Times, “and when you donate to the Japanese relief fund remember that far more dollars than we give will probably come back to us in the way of orders” (Hammond Lake County Times 1923c). These optimistic assessments were proven correct.

Figure 5: Hammond Lake City Times 1923, 2.

American steel producers saw opportunities that extended well beyond supplying steel sheets and wire nails used to construct temporary shelters made of American softwood timber, primarily Douglas Fir. They believed US producers might be called upon to meet significant new demands arising from “permanent” reconstruction. Japan, they believed, was certain to adopt new measures to “prohibit construction which does not resist earthquakes” (Iron Age 1923b, 623–624). “New Tokyo,” the editors of Iron Age continued, “will rise freed from all the flimsy structures which had become an increasing menace” in the capital. “Flimsy,” in the words of Iron Age editors, meant timber and brick buildings. Japan’s emergent capital, steel men predicted, would be a strong, modern, and permanent city built with “large quantities” of American steel. Steel executives and journalists alike asserted that American mills in “Pittsburgh and Gary can supply the steel that Japan will need for earthquake proof buildings” (Altoona Tribune 1923).

Initial damage assessment reports that filtered back to America led many executives, journalists, and steel producers to conclude that steel reinforced buildings in Tokyo had proven their “mettle” in the face of nature’s most destructive forces. “The only buildings which stood up under the earthquake,” F.S. Betz asserted from reports he claimed were relayed by the Japanese consul in Chicago, “were of American construction” (Hammond Lake County Times 1923d). This followed similar assertions shared by James Baird, President of the George Fuller Construction Company. Responsible for building Tokyo’s largest steel-reinforced buildings, including the Marunouchi Building, the Japan Oil Building, and the Nippon Yusen Kaisha (NYK) Building, Baird claimed that these iconic structures had survived the earthquake (Chicago Tribune 1923b; Iron Age 1923, 625). Though the buildings had suffered cosmetic damage to facades and exteriors, each survived virtually intact and now kept a lonely vigil over Japan’s otherwise ruined capital.

A more detailed report, shared by H.E. Root, vice president of sales, H.H. Robertson Company of Pittsburgh, confirmed Baird’s findings. Having returned to America from Tokyo in October 1923, Root spoke with authority when interviewed by the Pittsburgh Daily Post. “American-designed and fabricated steel and reinforced concrete buildings,” he declared, ‘defied’ the disaster while “all but one German and all Japanese steel-fabricated building went down in utter collapse” (Pittsburgh Daily Post 1923b). Wood buildings of all types, he noted, had been incinerated whether or not they survived the earthquake intact. Only steel would serve Japan’s future needs. Japanese people, Root asserted, had gained an intense admiration for American engineering principles and a “market for thousands of millions of dollars’ worth of American building materials” now existed. The H.H. Robertson Company, he revealed, had already received millions of dollars’ worth of orders for steel sheeting used as roofing for temporary shelters. If new engineering designs, materials, and construction technique were employed across Tokyo and Yokohama once permanent reconstruction commenced, he implied that a literal fortune awaited America steel producers.

Before that fortune materialized, steel producers found themselves inundated with orders for temporary reconstruction materials. Requests for wire nails and steel sheets (black, as well as galvanized), used in roofs and on exteriors in temporary housing, dominated early orders. As early as 6 September, US-based agents for Japanese construction interests had begun enquiring about available stocks of both items and initiated purchases on a large scale (Hammond Lake County Times 1923b; Indianapolis News 1923). By mid-September US Steel Corporation sheet mills operating at Farrell, Pennsylvania, and Carnegie mills in Youngstown, Ohio, were operating at full capacity (Pittsburgh Daily Post 1923). Throughout autumn, Japanese companies had placed orders ranging between 500 to 1,000 tons apiece on a regular basis at a price of $100 per ton (Washington Evening Star, 1923b). Initial estimates indicated that nearly $10 million had been spent on steel sheets alone by 31 October (Pittsburgh Press 1923). These orders, however welcome, were just the beginning of a profitable wave for steel producers.

In late October, steel executives focussed their attention on Washington DC, as the Japanese government opened bids via their embassy for the first large-scale reconstruction order that focused on steel. Sixteen companies were invited to submit bids to supply 13,000 tons of steel “black sheets,” 3,500 tons of galvanized corrugated steel sheets, 3,500 tons of galvanized steel sheets, and 3,000 tons of wire nails (Naimushō, 1926, 46). Bidding proved intense with twelve companies submitting detailed bids by the 1 November deadline (Naimushō 1926, 47–51). Given the size of the order, market watchers concluded that that for the first time in history, US steel producers, as opposed to British steel makers, “dictated the price” of steel sheet for Japanese purchase (Pittsburgh Post-Gazette 1923).

On 8 November, the Japanese government announced the contract recipients. The US Steel Corporation, the company that gave the largest single corporate donation to ARC Washington Division headquarters, received the largest share of the overall order. US Steel secured the lucrative right to supply the entire order of steel black sheets, 13,000 tons worth (Naimushō 1926, 53). The Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co., which donated $USD 25,000 to Japan Relief secured two thirds of the wire nail order (Naimushō 1926, 54–55). With one order, Japan had purchased a sizeable amount of steel and rewarded two of the steel companies that had proven most generous with humanitarian assistance. By the middle of 1924, Japan’s government purchased a total of 14,000 tons of galvanized sheets, 47,000 tons of black steel sheets, and 10,000 tons of wire nails at a total cost of 17.2 million Japanese Yen, roughly $USD 8.6 million (Naimushō 1926, 19–20). Giving to Japan paid handsome dividends to US steel producers. Though orders tapered once Japanese import duties on construction materials were reinstated on 31 March 1924, and remained low in 1925 as over supply secured during the non-tariff period outpaced demand, Japan’s importance to the US steel industry remained strong and then grew substantially over the following decades, as Table 1 illustrates.

Table 1: Total US Steel Exports and Exports to Japan, 1924-40

| Year | Total US steel exports in tons (2,240 lbs) | US steel exports to Japan in tons | Japan’s % of total US exports | Global rank |

| 1924 | 1,805,114 | 277,204 | 15 | 2 |

| 1925 | 1,762,551 | 132,674 | 8 | 3 |

| 1926 | 2,166,650 | 260,361 | 12 | 2 |

| 1927 | 2,183,157 | 278,206 | 13 | 2 |

| 1928 | 2,865,103 | 411,754 | 14 | 2 |

| 1929 | 3,087,357 | 426,974 | 14 | 2 |

| 1930 | 1,981,985 | 276,286 | 14 | 2 |

| 1931 | 968,945 | 98,886 | 10 | 2 |

| 1932 | 594,581 | 191,193 | 32 | 1 |

| 1933 | 1,341,183 | 593,207 | 44 | 1 |

| 1934 | 2,812,847 | 1,249,248 | 44 | 1 |

| 1935 | 3,063,659 | 1,201,391 | 39 | 1 |

| 1936 | 3,157,405 | 1,111,708 | 35 | 1 |

| 1937 | 7,578,677 | 2,784,420 | 37 | 1 |

| 1938 | 5,147,928 | 1,866,742 | 36 | 1 |

| 1939 | 6,083,576 | 2,238,861 | 37 | 1 |

| 1940 | 10,603,344 | 1,351,653 | 13 | 2 |

Source: United States Department of Commerce 1925, 703; 1925, 725; 1926, 716; 1928, 720; 1929, 755; 1931, 783; 1933, 665; 1935, 688; 1937, 711; 1939, 744; 1941, 817.

Did giving large, high-profile, and well-publicized donations to Japan by itself result in orders for US steel makers? It is impossible to reach a definitive conclusion as documents detailing deliberations over purchases within Japan’s government have not been uncovered. Could Japan have spread-out emergency and longer-term reconstruction orders among a larger number of US steel producers, rather than concentrate orders with a few of the largest donors? Yes, and had they done so, Japan might have secured these steel products more quickly than relying on one or two key producers whose production facilities were stretched to the breaking point to accommodate Japan (Pittsburgh Press 1923; Washington Evening Star 1923b). Could Japan have purchased steel in other international markets? Yes, steel producers within the United Kingdom, a country that gave far less humanitarian assistance to Japan following the disaster, likewise submitted bids for orders but found themselves at a distinct disadvantage in terms of results.

American corporations believed—expected—that humanitarian generosity would translate into future economic gains. To a large degree, those expectations were met both between 1923–24 and over the longer term for key exports such as steel and lumber. Japan’s post-disaster market for steel remained strong despite the fact that lumber imported from America served as the primary reconstruction material used for homes and small businesses across much of devastated Japan. Japan nevertheless remained one of America’s most important export markets for both steel and lumber up until the Second World War.

Multiple motives define corporate giving following natural disasters. In 1923, corporations from America’s industrial heartland gave out of sympathy, as an act to recognize Japan as an important customer or partner, and out of obvious commercial opportunism. To many corporations, Japan mattered and its perceived future importance grew markedly once reconstruction requirements became clear. Beyond humanitarian concerns, giving to assist sufferers in a country that would desperately require large volumes of products that could be produced in America made obvious business sense as well. US-based companies have acted similarly in more recent times. In assisting employees to raise $USD 1.3 million and matching it with a corporate donation of another $USD million following the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake, the Boeing Corporation recognized Japan’s status as a critically important customer. At the time of disaster, all of Japan Airline’s 162 aircraft in service and 92% of ANA’s aircraft fleet had been purchased from Boeing (Chong, 2018, 61–2). Given Boeing’s near dominance over commercial aircraft sales in Japan and the fact that airline fleets undergo almost continual renewal and eventual replacement, the potential consequences of not giving likely far outweighed any short-term burdens associated with the company’s small donations.

Recent scholarship on post-disaster Corporate Social Responsibility initiatives proves instructive in understanding humanitarianism today, though few cast their empirical gaze backward in time for any broader historical or contextual understanding. Competition and concern over public image, Gao and Hafsi have asserted, often drive corporate contributions, something that was certainly present in the minds of Westinghouse executives in 1923 (Gao and Taieb 2015, 311-12). Most recently, Azuma, Dahan, and Doh have suggested that corporate cash donations following disasters can act as a signal to outside investors of the firm’s future financial prospects—sound—and thus net a positive return for investors (Azuma, Dahan, and Doh 2023). Shareholders, Dennis Patten adds, might expect short-term, abnormally positive returns from companies who act generously in calamity’s wake (Patten 2008, 599). Expectations seemingly abound not just in the aftermath of disasters, but in the humanitarian engagements that follow. The Asbury Park Press articulated this sentiment with aplomb on 10 September 1923, writing:

Helping Japan, America helps itself. The gifts of goods and money and services are easily spared, and they will return a hundredfold in international goodwill and material profit, tho [sic] few are thinking of that now (Asbury Park Press, 1923).

Many, in fact, were thinking of material profits and international goodwill when they gave in 1923. Just as many do so today when they give.

References

Altoona Tribune, 1923. “Today,” 25 September, 11.

American National Red Cross, n.d. Folder 898.6/2 Japan Earthquake 9/1/23 – Finance and Accounts, Record Group ANRC (formerly Record Group 200), Box 707. United States National Archives and Records Administration.

American National Red Cross, 1924. American Red Cross Annual Report, 1923. Washington DC: US Government Printing Office.

Asbury Park Press, 1923. “Japan Relief,” 10 September, 8.

Kentaro Azuma, Nicolas M. Dahan, and Jonathan Doh, 2023. “Shareholder Reaction to Corporate Philanthropy After a Natural Disaster: An Empirical Exploration of the ‘Signaling Financial Prospects’ Explanation.” Asia Pacific Journal of Management. Accepted 21 February 2023, and published online.

Baltimore Sun, 1923. “Let’s Make a Treaty of Love,” 5 September, 4.

Buffalo Commercial, 1923. “Japanese Earthquake Disaster is New Factor of Outstanding Importance Suddenly Thrust into the Business Outlook,” 8 September, 5.

Buffalo Courier, 1923. “Crown Prince of Japan to Receive Westinghouse Gift,” 5 November, 9.

Buffalo Enquirer, 1923. “Latest Estimate 250,000 Dead in Yokohama and Tokyo, Many Homeless,” 5 September, 1.

Cabanes, Bruno. 2014. The Great War and the Origins of Humanitarianism, 1918-1924. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chicago Tribune, 1923. “Go Limit: Coolidge,” 5 September, 4.

Chicago Tribune, 1923b. “Building Genius of US Triumphs in Japan Quake – Skyscrapers Keep Vigil Over Ruined Cities,” 6 September, 3.

Chicago Tribune, 1923c. “US Electrical Firm Forms Big Japan Combine,” 23 November, 13.

Chong Pang Beatrice, 2018. “Altruism or Opportunism: International Humanitarian Assistance to Japan Following the 2011 Tōhoku Earthquake and Tsunami,” MPhil Thesis, University of Hong Kong.

Gao Yongqiang and Taïeb Hafsi, 2015. “Competition in Corporate Philanthropic Disaster Giving.” Chinese Management Studies, 9:3.

Cullather, Nick. 2015. The Hungry World. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Curti, Merle. 1963. American Philanthropy Abroad. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1963.

Cleveland Plain Dealer, 1923. “Millions Roam Miles of Quake Ruins, Tokyo One Vast City of Misery,” 6 September, 1.

Detroit Free Press, 1923. “Plague Famine Add to Horror of 250,000 Japanese Dead,” 4 September, 1.

Detroit Free Press, 1923b. “$60,000 Raised to Aid Japan,” 7 September, 2.

Detroit Free Press, 1923c. “Tokyo to Repay Thousand Fold,” 9 September, 3.

Ekbladh, David. 2009. The Great American Mission. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Fort Wayne Daily News, 1923. “Now Let’s See If We Can Squeeze Out Just a Little More,” 13 September, 4.

Hammond Lake County Times, 1923. “500,000 May Be Toll of Jap Cataclysm,” 4 September, 1.

Hammond Lake County Times, 1923b. “Steel Mills Get Call from Japan,” 6 September, 1.

Hammond Lake City Times, 1923c. “The Japanese Earthquake, Chevrolet Cuts Prices,” 7 September, 2.

Hammond Lake County Times, 1923d. “Jap Demand for Steel to Keep Plants Humming,” 14 September, 2.

Honolulu Advertiser, 1923. “Radio Fans are Liberal as KGU Fund is Opened,” 6 September, 1.

Indianapolis News, 1923. “Gary Steel Mills Get Big Japanese Orders,” 7 September, 1.

Indianapolis Star, 1923. “Gary to Get Huge Orders for Steel for Jap Building,” 8 September, 10.

Iron Age, 1923. 112:10 “Japan’s Consumption of American Steel,” 6 September, 625.

Iron Age, 1923b. 112:10 “Japan Offered Aid by American Steel Trade – Preferential Consideration to be Given for Steel Needs,” 6 September, 623-24.

Iron Age, 1923c. 112:11 “Japan and American Steel,” 13 September, 692.

Irwin, Julia F. 2013. Making the World Safe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Miami Herald, “Red Cross Campaign Here for Japanese,” 6 September, 2.

McCleary, Rachel. 2009. Global Compassion. New York: Oxford University Press.

Muncie Star Press, 1923. “Gary Steel Mills Get Big Japanese Order,” 8 September, 1.

Naimushō fukkōkyoku [Home Ministry Reconstruction Bureau], 1926. Rinji busshi kyōku jigyōshi [Catalogue of temporary reconstruction supplies]. Tokyo: Naimushō fukkōkyoku keiribu.

New York Times, 1923. “200,000 to Open Drive,” 6 September, 3.

New York Times, 1923b. “Relief Fund Appeal Made to Churches,” 16 September, 6.

New York Times, 1923c. “Relief Fund Near $3,000,000 Mark,” 18 September, 6.

New York Tribune, 1923. “Westinghouse Order from Japan,” 12 August, 14.

New York World, “Japan the Stricken,” 5 September, 4.

Nishimura Shigehiro, 2015. “The Making of Japan’s Patent Culture: The Impact of Westinghouse’s International Patent Management.” Kansai University Review of Business and Commerce, (16): 23-47.

Patenaude, Bertrand M. 2002. The Big Show in Bololand. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Patten, Dennis, M. 2008. “Does the Market Value Corporate Philanthropy? Evidence from the Response to the 2004 Tsunami Relief Effort.” Journal of Business Ethics, 81.

Philadelphia Inquirer, 1923. “Americans to Sail Early for Japan,” 28 September, 23.

Pittsburgh Daily Post, 1923. “Steel Firms Reports Well Booked with Orders,” 9 September, 53.

Pittsburgh Daily Post, 1923b. “American-Made Steel and Concrete Defy Earthquake and Fire,” 12 October, 2.

Pittsburgh Press, 1923. “Jap Steel Orders Boom Local Mills,” 2 November, 28.

Pittsburgh Press, 1923b. “Japanese Form Company with Westinghouse,” 27 November, 7.

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 1923. “Japanese Steel Orders Pour in on Pittsburgh,” 2 November, 7.

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 1923b. “Japanese Electric Company to Utilize Local Firm’s Patents,” 24 November, 18.

Schencking, J. Charles. 2019. “Giving Most and Giving Differently,” Diplomatic History. 43:4.

Schencking, J. Charles. 2021. “Generosity Betrayed: Pearl Harbor, Ingratitude, and American Humanitarian Assistance to Japan in 1923.” Pacific Historical Review, 91:1.

Seattle Post Intelligencer, 1923. “$100,000 Japan Relief Fund Drive Launched in Seattle,” 5 September, 1.

Seattle Post Intelligencer, 1923b. “Seattle Fund for Quake Area Passes $15,000,” 6 September, 1.

St. Louis Post Dispatch, 1923. “American Relief Fund for Japanese Half Subscribed,” 8 September, 3.

St Louis Star and Times, 1923. “Emerging,” 12 September, 16.

United States Department of Commerce, 1925. Foreign Commerce and Navigation of the United States 1924. Washington DC: US Government Printing Office.

United States Department of State, n. d. Records of Department of State Relating to Internal Affairs of Japan, 1910–29. File 894.48 – Calamities, Disasters. Record Group 59. Reel 23. United States National Archives and Records Administration.

United States Department of State, n.d. (b) Records of Department of State Relating to Internal Affairs of Japan, 1910–29. File 894.51 – Financial Conditions. Record Group 59. Reel 26. United States National Archives and Records Administration.

Wall Street Journal, 1923. “C.E. Mitchell Deplores Loss of Life,” 5 September, 13.

Wall Street Journal, 1923b. “Disaster May Help Steel,” 5 September, 3.

Wall Street Journal, 1923c. “Japan in Market for Much Steel,” 7 September, 9.

Wall Street Journal, 1923d. “Japan Now Like Western Markets,” 24 September, 8.

Wall Street Journal, 1923e. “Japan’s Electric Companies Expand,” 3 November 6.

Wall Street Journal, 1923f. “Westinghouse Official Explains Agreement,” 28 November, 11.

Washington Evening Star, 1923. “President Asks Contributions for Japan,” 4 September, 4.

Washington Evening Star, 1923b. Japan Buys Steel,” 6 November, 24.

Watenpaugh, Keith David. 2015. Bread from Stones: The Middle East and the Making of Modern Humanitarianism. Berkeley: University of California Press.