Abstract: The decade following the Great Kantō Earthquake of 1923 witnessed a proliferation of writings by officials, academics, businessmen, and journalists on the economic consequences of the disaster. This abundance of contemporary analysis stands in strong contrast to the relative scarcity of subsequent scholarly studies of many aspects of the disaster’s economic impact. In this article, I suggest that part of the reason for this relative lacuna lies in broader trends within economics and economic history scholarship. In particular, a focus on quantitative analysis and macro-level indicators has led to the conclusion that over the longer term, the Kantō earthquake, like similar disasters elsewhere, did not matter that much for the development of the country’s economy. I also show that although recent advances in economic theory, especially in the economics of disasters, can strengthen historians’ analyses of the economic consequences of the 1923 disaster, many of these ‘new’ conceptual frameworks were foreshadowed by contemporary commentators seeking to analyze the impact of the disaster on the economic life of the nation. Ikeuchi Yukichika’s book Shinsai Keizai Shigan, published in December 1923, is a particularly good example of how, just like recent disaster economists, Japanese contemporaries viewed the analysis of markets as the key to understanding both the economic impact of the disaster and how best to rebuild Japan’s economy.

Keywords: Earthquake; disaster; economy; historiography; markets

In a remarkable book, Shinsai Keizai Shigan (Personal View of the Earthquake Disaster Economy), published in December 1923, the author, Ike(no)uchi Yukichika, articulated the widely shared view that the earthquake and fire three months earlier had set Japan’s economy back by many years, noting how it had led to an estimated loss of one-eighth of Japan’s national wealth and generated immense repercussions for the material life of the whole country. Pictures taken in the aftermath of the 1923 disaster speak volumes about the extent of the damage, and the scale of economic loss was sufficient to generate claims that “the economic organization of the imperial capital has been destroyed almost down to its very foundations” (Nōshōmushō Shōmukyoku 1924, 24).

Figure 1: Yokohama after the Earthquake and Fires (Yokohama Central Library, 1923).

Ikeuchi’s volume was just one of the many in-depth analyses of the economic consequences of the disaster produced by Japanese officials, businessmen, academics and economic journalists in the months and years that followed. These analyses continued to appear into the early 1930s. The country then found itself facing two major man-made disasters of arguably even greater proportions: the Great Depression that followed the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and the Second Sino-Japanese and Pacific Wars. For many Japanese, the economic hardships of 1923 paled into insignificance compared to the economic damage wrought by these new events, and as memories of the earthquake itself receded, replaced by new economic challenges, so too did the widespread and frequent publication of reports and analyses of the economic effects of the disaster.

This wealth of exhaustive contemporary analysis on the economic dimensions of the disaster stands in strong contrast to the relative paucity of later scholarly studies on this topic.1 While the financial repercussions of the disaster have been researched in some depth (e.g. Nihon Ginkō Hyakunen Shi Hensan Iinkai 1983; Okazaki, Okubo, & Strobl 2021), and recent scholarship has been informed by advances in economic geography and the study of market integration (e.g. Imaizumi 2008, 2014; Imaizumi et al. 2016; Hunter & Ogasawara 2019; Okazaki et al. 2019), many other economic aspects have remained largely unexplored. Nor has there been any significant academic exploration of the widespread and well-documented responses of contemporaries to the multiple economic crises that confronted them in the immediate aftermath of the earthquake, crises of a kind that we now recognize as common to many such one-off catastrophes.

In this short piece, I argue that part of the reason for this relative lacuna in the historiography of the 1923 disaster lies in broader emphases within economic historical and economics scholarship through the second half of the 20th century. I suggest that contemporary writings on the economic impact of the disaster, such as that of Ikeuchi, were far more than detailed descriptions of the course of events. They offered rigorous and insightful analyses of the mechanisms behind what occurred, foreshadowing more recent scholarship on the economics of disasters. Most notably, they focused on the importance of markets and market activity in diffusing the impact of the disaster across the nation and even across the globe.

Measuring the Economic Cost

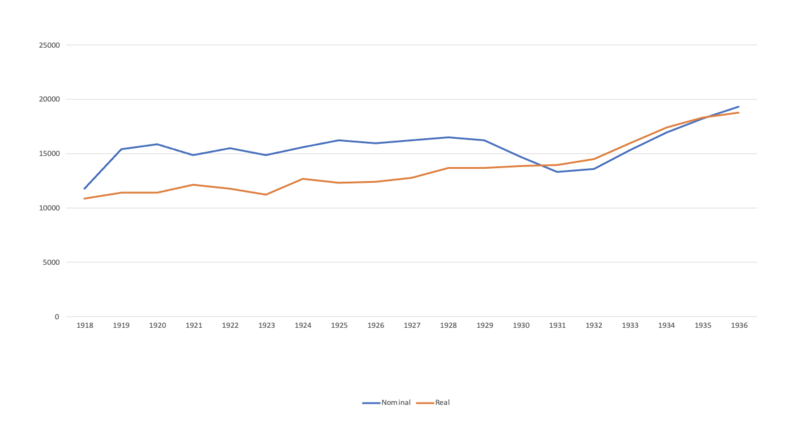

One factor that has contributed to the relative absence of scholarship on the 1923 disaster is a more general emphasis on numbers, national accounting, and the macroeconomic picture. Quantification has long been important to economic history, but became increasingly so after the growth of cliometrics (the so-called New Economic History) from the 1960s and the appearance of new technologies that made it easier to handle significant amounts of quantitative historical data. These new techniques have facilitated measurements of the economic costs and scale of destruction from one-off disasters such as earthquakes, and their importance in longer term trajectories. In the case of the Great Kantō Earthquake, we now have far more reliable estimates of the total loss from the destruction and how it fits into the longer-term picture. We now have data that suggests that, if we include building structures of all kinds, production capacity, and physical infrastructure such as utility, transport and communications systems, the damage wrought by the 1923 disaster amounted to over a third of the country’s 1922 GNP (Imaizumi, Ito & Okazaki 2016, 54). When seen in longer-term context, however, this figure, large as it is, does not suggest that the 1923 disaster was of major or lasting economic importance. As shown in Figure 2 below, the statistical record indicates that the catastrophe caused only a slight and temporary downturn in Japan’s national income, and what negative impact there was paled in comparison to the damage wrought by the Great Depression of the early 1930s. The fact that within relatively few years of the 1923 disaster most macroeconomic indicators had reverted to trend meant, in other words, that whatever the immediate crises facing survivors, over the longer term the disaster did not really matter for Japan’s economy. Its impact was in many respects reduced to being a temporary ‘blip.’

Figure 2: Japan, Nominal and Real National Income, 1918-1936. ¥m., real income at 1934-36 prices (Miwa & Hara 2007, 2).

The evidence that the Great Kantō Earthquake merely marked a short hiatus in Japan’s longer term economic trajectory seemed to align with longstanding assumptions about the economic impact of disasters. John Stuart Mill, writing in 1848, spoke of ‘‘the disappearance, in a short time, of all traces of the mischiefs done by earthquakes, floods, hurricanes, and the ravages of war,” and recent historical work has drawn similar conclusions regarding other major natural disasters, namely that many such disasters have relatively little impact over the longer term (for examples, see Cavallo et al. 2013; Singleton 2016). They may even open up new opportunities. So, quantification has certainly enhanced our historical understanding, but has given us only part of the whole story. Putting plausible numbers on the more indirect costs of the disaster—for example, loss of human capital, knowledge, and the possibilities for knowledge exchange—has remained elusive. A relative absence of research on sub-macro level issues has perhaps been exacerbated by the time-consuming and challenging task of data collection and analysis, while prioritizing numbers may have contributed to an undervaluing of historical questions that have to be addressed through qualitative research. Economists’ intensive analysis of slow build disasters such as famines and the ways in which they can be caused, exacerbated, and alleviated by the operation of the market (e.g. Sen 1983; O’Grada 2009), has not been matched by equivalent studies of one-off disasters such as that of Japan in 1923. Moreover, quantification has little to say about the lived economic experiences of individuals and small social groups that lie at the core of disciplines such as social history or anthropology. More in-depth consideration of these issues might well lead us to re-evaluate the significance of the disaster for Japan’s economy and the economic activity of its citizens. And this is where Ikeuchi and his contemporaries come in.

1923 Perspectives

For survivors in 1923, the clear priority was rebuilding livelihoods; they continued to follow Adam Smith’s mantra of ‘truck, barter and exchange’, and made economic decisions in line with this imperative. The extensive commentary on the disaster’s effects on the economy was integral to this process as politicians, economists, businessmen, and journalists sought to analyze the economic responses of people and markets with a view to facilitating recovery. The focus on market activity in this commentary was explicit. Japan in 1923 was overwhelmingly a market economy. Economic intervention by the government invariably sought to manipulate the market, and not to substitute for it. It followed that markets and market activity would also frame the economic impact of a disaster, an assumption doubtless born of Japan’s shared and long experience of frequent natural disasters and the responses that they could provoke. The clarity with which this focus on markets was articulated may also, in the case of some commentators, have been sharpened by a high level of advanced economics training, either in Japan or overseas. Nowhere is this focus more clearly articulated than in Ikeuchi’s Shinsai Keizai Shigan.

Figure 3: Front cover of Ikeuchi Yukichika’s Shinsai Keizai Shigan.

Information about Ikeuchi is hard to come by, but we know that he graduated from Nihon University in 1911 and then resided in the United States for around ten years, studying applied economics at the University of California. Acting as advisor to a number of major Japanese businesses following his return, he seems around the time of the earthquake to have been serving as advisor to the Takeuchi Genbutsuten, a firm engaged in spot transactions in Osaka, perhaps alongside other posts (Asahi Shinbun 1924a, 1924b). Whatever the case, the publication by Ikeuchi of a detailed and well-evidenced 300-page book in early December 1923, barely three months after the disaster, suggests that he was both a committed researcher and a fast writer. Ikeuchi’s stated objective in publishing his volume was to produce an economic history of the Great Kantō Earthquake that would also serve as a reference source for the business world for the future. Spelling out in detail the economic consequences of the disaster and supporting his conclusions with an enormous amount of statistical data and qualitative evidence, Ikeuchi’s book is a significant work of scholarship and analysis. While not playing down the extent of loss and difficulties ahead, the picture that he draws is not one of unmitigated tragedy. He acknowledges that certain economic benefits may ultimately come out of what has happened, since the scale of the losses were such that the rebuilding process would generate a significant consumption stimulus (Ikeuchi 1923, 17), and he expresses confidence that the immediate difficulties would ultimately be overcome. But the best recovery could only be achieved, he suggests, through a proper understanding of the exact ways in which the disaster had affected economic activity and those involved in it. And as a basis for that understanding, he offers a novel and instructive analytical framework, subdividing the disaster’s economic impact into three categories: natural effects, regional effects and man-made effects. Natural effects consist of both ‘direct’ effects (human and material damage and destruction) and what Ikeuchi refers to as ‘indirect’ effects. The latter include shortages and surpluses of goods—relief and rebuilding goods, for example, were in short supply while demand for coal had collapsed due to the destruction of the factories that made use of it—unemployment, bankruptcies, as well as credit, financial, and insurance difficulties. A lack of credit following the destruction of assets, Ikeuchi notes, meant that many transactions could only be carried out on a cash basis. Regional effects he defines as the consequence of the existence of mechanisms that transmit the impact of the disaster beyond the immediate area of destruction in Kantō. These mechanisms consisted of direct links between different parts of the country through economic organizations and market transactions, demand for goods from provincial production areas (sanchi), the rural to urban economic nexus, and the regional economic balance between Kantō and Kansai. For example, businesses and individuals in Kansai, Ikeuchi notes, were potentially well placed to try and take advantage of the difficulties in Kantō, but any benefits could be outweighed through the loss of branch offices or investments in the capital. Man-made effects were the results of actions by the authorities and other institutions. These included, among many others, emergency requisitioning and relief provisions, an anti-profiteering ordinance, and a one-month moratorium on due payments in the disaster area, as well as tariff and tax suspensions. All of these factors were analyzed in enormous detail in the book.

While Ikeuchi’s work was unusual in the extent to which it sought to provide an analytical framework for what had occurred, much of his analysis was echoed in the other articles, reports and publications that appeared in the months following the disaster. Writers described in immense detail the nationwide diffusion of the impact of the destruction, the shifts in supply and demand, the complaints of shortages and surpluses across the country, and the ongoing effects of transport and utility disruption. “Prices must, of course, be expected to rise,” stated one analyst (Tōyō Keizai Shinpō 1923, 407), considering the sudden shortages not only of basic commodities, but of many other products that had become commonplace in the earthquake’s aftermath. They realized that the potential for damaging economic consequences, both direct and indirect, was magnified by the fact that the devastated area around Tokyo was the hub of an increasingly centralized national economy and also home to Yokohama, which had in 1922 accounted for over 40% of the value of Japan’s commodity trade, with a monopoly on the country’s most important export, raw silk. Price changes in the capital district were all but certain to be spread across the country. The closer a provincial area was to the devastated region, the more likely it was to be affected, but there were complaints of shortages and surpluses of goods as well as price changes from northern Hokkaido down to southern Kyushu. The post-disaster modification of normal market behavior was also the subject of numerous reports. With both the desperate and the less desperate anxious to get the best possible prices for the limited supplies they had to sell, retail prices surged, forcing the state to introduce anti-profiteering measures in the areas affected by the disaster. Nor were residents of regions such as Kansai and Tōhoku immune from accusations of profiteering, and some provincial authorities also found it necessary to try and regulate prices or supplies.

In the view of contemporaries, therefore, this was a national disaster and not just a regional one. While it had been centered on the capital region, its economic impact was experienced by many citizens right across the country, whether in cities, towns or rural areas. This widespread impact was intensified by the country’s high degree of national market integration, its relatively centralized financial and political system, as well as its centralized informational and physical infrastructure. The fact that Kantō was also a focal area for Japan’s foreign trade helped to spread the ripples even further to international markets. The disaster caused major problems for the yen exchange rate and Japan’s balance of payments situation, as well as temporarily disrupting the New York silk market. Under these circumstances, rebuilding Tokyo and Yokohama was a necessary, but not sufficient condition for economic recovery. As Yokoi Tokiyoshi, head of the Tokyo University of Agriculture, wrote in December 1923, “Voices calling for the revival of the capital are very loud, but those calling for the revival of markets are very quiet… The economies of Tokyo and Yokohama must be rebuilt for the sake of the countryside” (Yokoi 1923, 5). Ikeuchi and other contemporary analysts thus overwhelmingly focused on market transactions both as a mechanism for spreading the economic impact of the disaster and as fundamental to the recovery of Japan’s economy.

Foreshadowing Later Theory?

Study of the economics of disasters has blossomed over the last 25 years; we now recognize that localized one-off disasters are more than mere economic blips, and that they have national and global ramifications for politics, economies, and societies. More recent conceptual frameworks have in some respects ‘caught up’ with where Ikeuchi and his fellow commentators were in 1923. For example, in calculating the magnitude of a disaster, economists now routinely differentiate between direct and indirect costs: direct costs are the actual cost of what is physically destroyed and lost, while indirect costs arise from the knock-on effects of the destruction that has occurred. The notion of indirect costs has fed into scholarship on the importance of the market in diffusing the economic impact of large-scale natural disasters well beyond the disaster zone. This distinction between direct and indirect costs closely mirrors the similar categories adopted by Ikeuchi. We also now take it for granted that a major disaster in almost any location in the world can have an international impact through mechanisms such as global supply chains. One widely accepted framework refers to ‘ripple effects’ (see Hallegatte & Przyluski 2010). These effects are consequent on factors such as the shifts in supply and demand for different goods caused by the destruction and the disruption of transport and utility services, again mirroring Ikeuchi’s ‘regional effects.’ Just as importantly, economists now accept that in a disaster situations, groups and individuals modify their market behavior. That is, in a disaster situation, people may make economic decisions that are different from those that they might normally make. For example, economic actors outside the disaster area may demonstrate a significant degree of altruism and make donations of food or money, or send needed supplies at reduced cost, but they are equally likely to identify strategies that would generate increased profits in the face of others’ misfortune. The market consequences of this complex situation are not only shortages and surpluses of different goods, but also that prices fall out of equilibrium, credit mechanisms are disrupted, exchange rates and the balance of payments situation change, and there is a significant loss of trust in market transactions.

The empirical evidence on the course of events following the Kantō disaster supports all these theoretical suppositions, including the mismatch of supply and demand, the diffusion of price changes through the market, the problems with credit mechanisms and trust, and the suspension of normal market behavior. Just as significant, however, is the fact that many of the outcomes predicted by recent theory were documented and analyzed in depth by researchers and journalists at the time: price changes that were not always consistent with actual supply and demand; huge disparities between retail prices and wholesale prices (which were easier to control); and major disruption in credit and finance systems associated with loss of assets and business records, loss of trust, and pressure to engage in unsecured lending all resulted in a widespread reversion to cash (rather than credit) dealings. The economics of disasters may therefore have given us a more coherent framework for analyzing the economic impact of a major natural disaster in a market economy, but it seems unlikely that Ikeuchi and his Japanese contemporaries would have been greatly surprised by the focus of this more recent work.

References

Asahi Shinbun (1924a) Book advertisement, 1 November.

Asahi Shinbun (1924b) “Gekisenchi kara (sanjū),” 26 April, 2.

Cavallo, Eduardo, Sebastian Galliani, Ilan Noy & Juan Pantano. (2013) “Catastrophic Natural Disasters and Economic Growth,” Review of Economics and Statistics 95(5), Dec.

Yokohama Central Library (1923) “The 1923 Great Kantō Earthquake (view from Kotobuki Junior School in Yokohama),” https://www.city.yokohama.lg.jp/kurashi/kyodo-manabi/library/shiru/kantodaishinsai/menu/moyo/picture2/shinsai-d1.html.

Hallegatte, Stephane & Valentin Przyluski. (2010) “The Economics of Natural Disasters: Concepts and Methods,” Policy Research Working Paper 5507, World Bank Sustainable Development Network, Dec.

Hunter, Janet, & Ogasawara, Kōta. (2019) “Price Shocks in Regional Markets: Japan’s Great Kantō Earthquake of 1923,” Economic History Review 72(4), Nov.

Ike(no)uchi, Yukichika. (1923) Shinsai Keizai Shigan – Taishō Shinsai Keizaishi to waga Zaikai Shōrai no Suii, Tokyo: Konishi Shoten, Dec.

Imaizumi, Asuka. (2008) “Tōkyō-fu Kikai Kanren Kōgyō Shūseki ni okeru Kantō Daishinsai no Eikyō: Sangyō Shūseki to Ichijiteki Shokku,” Shakai Keizai Shigaku 74(4).

Imaizumi, Asuka. (2014) “Kantō Daishinsaigo no Tōkyō ni okeru Sangyō Fukkō no Kiten: Jinkō to Rōdō Juyō no Dōkō ni Chakumoku shite,” Shakai Kagaku Ronshū (Saitama Daigaku Keizai Gakkai) 142, June.

Imaizumi, Asuka, Kaori Ito & Tetsuji Okazaki. (2016) “Impact of Natural Disasters on Industrial Agglomeration: The Case of the Great Kanto Earthquake in 1923,” Explorations in Economic History 60.

Miwa, Ryōichi, & Hara, Akira. (2007) Kingendai Nihon Keizaishi Yōran, Tokyo: Tōkyō Daigaku Shuppankai.

Nihon Ginkō Hyakunen Shi Hensan Iinkai. (1983) Nihon Ginkō Hyakunen Shi Vol.3, Tokyo: Nihon Ginkō.

Nōshōmushō Shōkōkyoku. (1924) Kantō Chihō Shinsai no Keizaikai ni oyoboseru Eikyō, Tokyo: Nōshōmushō.

O’Grada, Cormac. (2009) Famine: A Short History, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Okazaki, Tetsuji, Toshihiro Okubo & Eric Strobl. (2019) “Creative Destruction of Industries: Yokohama City in the Great Kanto Earthquake, 1923,” Journal of Economic History 79(1), March.

Okazaki, Tetsuji, Toshihiro Okubo & Eric Strobl. (2021) “The Bright and Dark Side of Financial Support from Local and Central Banks after a Natural Disaster: Evidence from the Great Kantō Earthquake, 1923, Japan,” Canon Institute for Global Studies Working Paper Series no.21-001E.

Sen, Amartya. (1983) Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Singleton, John. (2016) Economic and Natural Disasters Since 1900: A Comparative History, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Tōyō Keizai Shinpō 1067 (1923) Untitled article, 1 October, 407.

Yokoi, Tokiyoshi. (1923) “Nōson ni oyoboseru Shinsai no Eikyō to sono Taisaku,” Shimin 18(11), Dec.

Notes

There are, of course, exceptions to this generalization, including the SERUND Project at Hitotsubashi University in the 1980s, which published several working papers.