Abstract: This review plumbs the deep narrative structure of Hong Yunshin’s “Comfort Stations” as Remembered by Okinawans during World War II (Brill, 2020). It begins by situating her work in the historical tensions between Okinawa and mainland Japan as viewed through their disparate responses to the “comfort women” issue. Hong’s discussion of military “comfort stations” during the Battle of Okinawa focuses not on the sexually enslaved, but on the collateral trauma of Okinawans who witnessed that violence in their daily lives. Tomiyama hightlights the author’s emphasis on the postwar ressurection and reworking of battlefield memories, which today have become productive sites of remembrance and resistance. He joins Hong in noting that the memory work of war survivors is part of an ensemble of collective postcolonial practices that are shaping a self-reflective and distinctively Okinawan consciousness. This process of discovery, Tomiyama writes, challenges the territorial and ethno-nationalist assumptions of the contemporary Japanese state.

Keywords: “comfort stations” (ianjo), “comfort women” (ianfu), redress movement, military sexual violence, politics of death (necropolitics), Japanese military occupation of Okinawa, the Battle of Okinawa, U.S. military occupation of Okinawa, U.S. military bases in Okinawa, Japan’s postwar culture of historical denial, postcolonial memory, modern sovereignty and the nation state, colonial and neocolonial foreclosure (“exceptionalization”), Inner Japan and Outer Japan, internal colonies, alegality, presentiments of death, the encoding of racial and sexual bias, the violence of everyday life, an experiential epistemology of war, sites of remembrance and resistance, relational spaces, Okinawa’s “new communal”

Translator’s Introduction

Robert Ricketts

Tomiyama Ichirō, professor in the Graduate School of Global Studies at Doshisha University, Kyoto, wrote one of the earliest reviews of Hong Yunshin’s Memories of the Okinawan Battlefield and “Comfort Stations” when it appeared in Japanese in 2016.1 He was also among the first to comment critically on the English version, “Comfort Stations” as Remembered by Okinawans during World War II, after its release by Brill in 2020.2

Professor Tomiyama is ideally placed to introduce the English version of Hong’s book. His academic interests are eclectic, ranging from agrarian economic history to Japanese history, Okinawan studies, cultural criticism, and the history of ideas. But the core of his research and writings deals with modern Okinawa and the related issues of the Japanese nation-state, colonialism, militarism, violence, gender, postcolonial memory, and hopes for a better world (ama yuu in Okinawan).3

Hong Yunshin (Ph.D.) is a visiting fellow at the Tokyo Center for Asian Pacific Partnership of the Asian Research Institute, Osaka University of Economics and Law, and a Special Fellow at the Waseda Institute of Asia-Pacific Studies, Waseda University. She lectures at several Tokyo universities and speaks and writes extensively on Okinawa, women, militarization and war, and sexual violence. Her work centers on Okinawan remembrances of wartime and postwar military sexual violence (Japanese and American) and the relevance of postcolonial memory as a constituent element of a resurgent Ryukyuan consciousness.4

Hong first visited Okinawa in 2002, having just arrived in Japan with a bachelor’s degree from Chung-An University in Seoul to begin graduate work at Waseda University. Her first encounters with survivors of the Battle of Okinawa date from that year. After completing her master’s degree in 2004,5 she began intensive fieldwork in Okinawa. In 2012, Hong submitted her Ph.D. thesis, “Koreans and the Politics of ‘Sex and Life’ during the Battle of Okinawa: Military ‘Comfort Stations’ as Sites of Remembrance,”6 laying the groundwork for the volume under review.

Why Okinawa?

“Why Okinawa?” is a question Hong ponders in the introductory and concluding chapters, the appendix, and the afterword. “Instinctively,” she writes, “I had often tried to position myself in Japan as a victim rather than an aggressor or accomplice. In Okinawa, however, I could abandon that stance […] and free myself from an implicit statist duality—’Korean’ vs. ‘Japanese,’ ‘Okinawan’ vs. ‘Japanese,’ ‘Korean’ vs. ‘Okinawan.’” There she discovered “the political space and peace of mind […] to transcend conventional paradigms and explore the hidden complexities of Okinawan society” (Hong 2020: 19). Hong examines military sexual slavery through the institution of the “comfort stations” (ianjo) rather than the experiences of the “comfort women” (ianfu)7 themselves. This choice, she writes, allows her to avoid two pitfalls: identifying uncritically with the Korean captives who staffed the ianjo and minimizing the remembered war experiences of Okinawans who observed their ordeal. That perspective “ultimately reveals more about the nature of military violence than would a conventional analysis centered exclusively on the sexually enslaved” (p. 502).

Hong poses the crucial question: “What [postwar] lessons did Okinawans draw from the violence they witnessed in the ianjo?” (p. 20). As Tomiyama remarks, that query is where her studies intersect with his own research on the foundations of sexual and colonial violence in wartime Okinawa and their postwar sequelae. Tomiyama is wary of conventional academic analyses, which tend to produce narratives reinforcing the premises of modern sovereignty, with its territorial and ethno-nationalist imperatives. Writing a different history, he says, requires an idiom able to express an intrinsically Okinawan experience that positions itself in the contested gray zones between two complicit sovereignties, Japanese and American. Like Hong, he discovers that alternative language encoded in postwar memories of the battlefield and the U.S. military presence in Okinawa.

Here, a brief outline of the book will provide background for Tomiyama’s review.

Synopsis

“Comfort Stations” as Remembered by Okinawans during World War II covers Okinawa from 1941 until 1952—the years leading up to, including, and following the Battle of Okinawa, which was waged between late March and late June 1945.

Hong begins by demonstrating that militarized violence against women did not originate in the comfort stations. Its roots lay in a gathering storm that had begun to buffet Northeast Asia in the late 19th century as Japan mobilized capital and built a modern war machine in its forced march to industrialize and expand its influence in Asia and the Pacific. Her narrative unfolds against the backdrop of events leading up to the Asia-Pacific War (1931–45).8

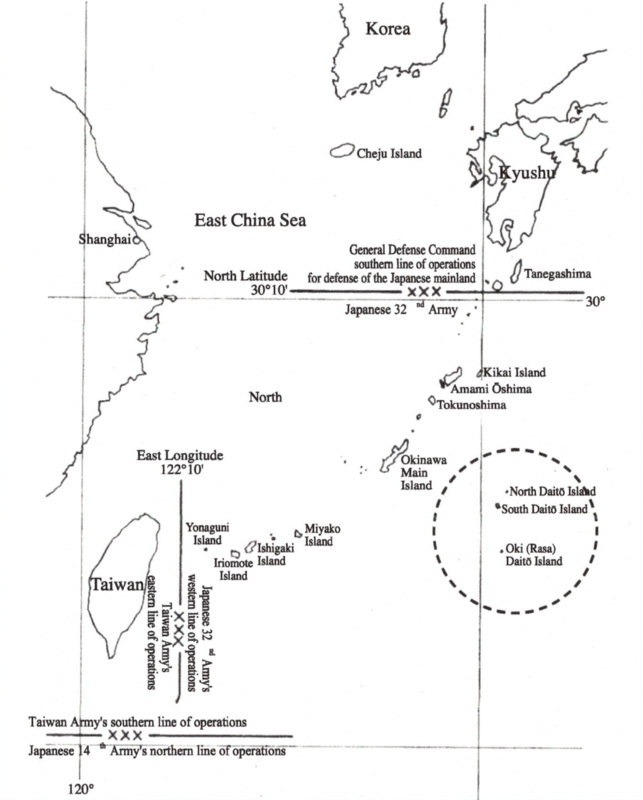

The author divides her study into three sections. Part 1 (Capital and Comfort Stations) consists of Chapter 1, which describes Japan’s colonization in the late 19th and early 20th centuries of the three Daitō Islands (Daitōjima) that would demarcate Okinawa’s eastern perimeter. Agrarian capitalists developed a plantation economy in the tiny island group, and the discovery of extensive phosphate reserves made the islets a strategic national asset. Following the empire’s southward advance into the Pacific in the early 20th century, the imperial navy established a foothold in the Daitōs in the mid-1930s, installing a rudimentary airbase. The navy opened Okinawa’s first comfort station (ianjo) near the air facility in 1941, sometime before the Japanese attacks of early December on British Malaya and Pearl Harbor that triggered the Pacific War. In late March 1944, as U.S. forces island-hopped across the Pacific, the Japanese 32nd Army was activated to defend the Ryūkyūs. A regiment was stationed in the Daitōs, the airbase was enlarged, and new ianjo appeared.

Map 1: Japanese 32nd Army area of operations in the Southwest Islands, 1944–459

Part 2 (Comfort Stations Move into the Villages) comprises chapters 2–6. Chapter 2 discusses the origins of the Japanese comfort women system in China, its introduction to Okinawa, and the opposition the ianjo aroused locally. The chapter outlines the 32nd Army’s Okinawan deployment in the early spring of 1944 and the archipleago’s subsequent transformation into a vast air fortress consisting of a nexus of interlocking airbases on each island group. As army engineers, soldiers, and Okinawan corvée laborers raced to build 15 military airfields complete with defensive emplacements, small engineering and construction units toiled alongside them erecting special “facilities for sexual comfort” (seiteki ian no tame no shisetsu, p. 84).

Table 1: Military order to erect a temporary comfort station (Iejima, June 1944)10

|

50th Airfield Battalion Order June 4 20:00 Iejima Barracks |

|

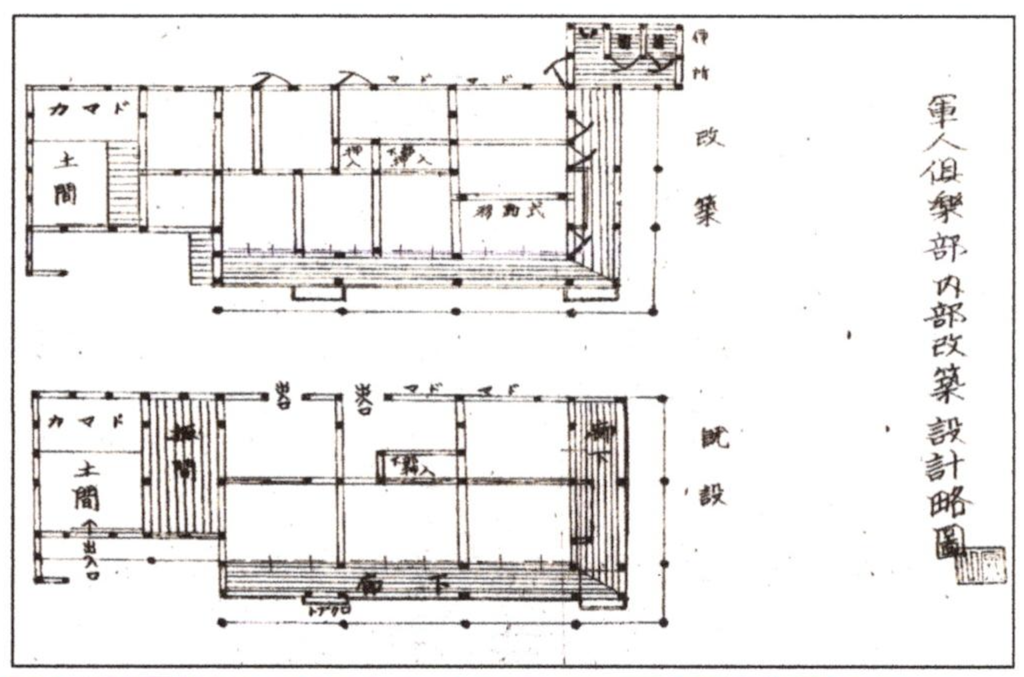

Fig. 1: Comfort station floorplan: “military service club” before (bottom) and after (top) enlargement (Yomitan Airfield, December 1944)11

The U.S. assault on Okinawa began in late March 1945, with the bombardment and capture of the offshore Kerama Islands, and spread quickly to Okinawa Main Island, which was invaded on April 1. The battle culminated three months later in the disintegration of the 32nd Army on June 23, signaling the end of large-scale organized Japanese resistance in the archipelago. Most surviving Japanese units officially surrendered to the U.S. army on September 7, although low-intensity guerrilla warfare flared sporadically in the northern part of the main island until early 1947. Between one-quarter and one-third of the prefecture’s civilian population died during the battle.12 The great majority of comfort women (ianfu) also perished in the fighting. Only a small number lived to be repatriated to Korea by U.S. forces in late 1945.

Hong’s book follows the invasion from battlefield to battlefield but is not a military history of the Okinawan war. Instead, she reconstructs the steady militarization of the village life space as the Japanese garrison dug in to await the U.S. offensive. Chapters 3–6 examine in rough chronological order the installation of airfields and their comfort stations on the main island, featuring case studies of Iejima Island in the north (chap. 3), Yomitan and Kadena in the central district (chaps. 4 & 5), and Urasoe and Nishihara in the south-central region (chap. 6).

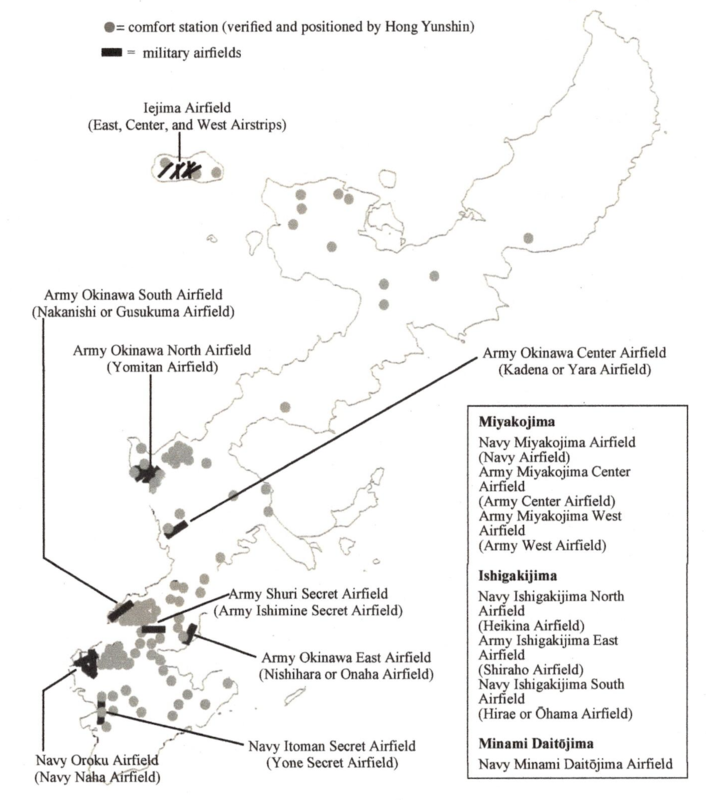

Map 2: Military airfields and comfort stations on Okiniwa Main Island13

Of partricular interest are Okinawan accounts of casual interactions with Korean ianfu and Okinawan juri (prostituted women from Naha’s licensed quarter in Tsuji). Researchers estimate that at least 1,000 Korean women were brought to Okinawa as comfort women during the war. A smaller number were Okinawans. A 1957 Ryukyu Government survey concluded that, “There were usually two comfort stations per regiment […]. In all, some 500 such women were attached to military units. These women and girls […] from Tsuji had been assigned to each military district on direct orders from the army” (p. 294).

In these chapters, Hong describes how the ianjo gradually affected relations between Okinawan civilians and the military after the Ryūkyūs came within bombing range of U.S. carrier aircraft. On October 10, 1944, American warplanes launched catastrophic air strikes on Naha city and military installations across the prefecture, including airfields and comfort stations in private homes with prominent red tile roofs. The so-called 10.10 surprise attack forced the 32nd Army to abandon its air-defense strategy and shift defensive positions from the main island’s central west coast to the south-central Shuri highlands.14

The October 10 debacle killed hundreds of civilians, eroded Okinawans’ trust in the army, and created new tensions with the troops. In the wake of that disaster, Japanese army units strengthened internal controls over the comfort stations, now viewed as vital military assets. By introducing rules that imposed stringent conditions on access to official military sex, army commanders sought to tighten discipline in the ranks and prepare unruly troops for combat. But the increasing regimentation of sex facilities had other uses, as well.

By the late autumn of 1944, most infantry divisions had set up ianjo control boards to micromanage these “rear-area support facilities” (kōhō shisetsu) at the brigade, battalion, and company levels. Sex venues were declared “off-base areas” and placed out of bounds to Okinawan residents, causing entire segments of the village life space to morph into no-go zones. These sequestered sites became part of a patchwork of restricted security areas where military counterintelligence operations could proceed unimpeded. The special zones isolated local communities from neighboring villages while subdividing each internally, thereby facilitating the army’s search for “subversive elements.” Immediately targeted as spies, Hong notes, were civilians who openly protested sex crimes and other abuses by Japanese soldiers.

Part 3 (Comfort Stations on Islands “Invaded” and “Not Invaded”) includes chapters 7–9. Chapter 7 looks at the comfort stations in the main island’s far north, where no military airfields were built. The pivotal Chapter 8 is outlined separately below. Chapter 9 is a case study of Miyakojima, a heavily fortified but remote southern island that the invaders sidestepped on their way to Okinawa Main Island. There, comfort women regularly attended periodic cultural performances (engeikai) by Japanese troops and, ironically, were expected to perform Arirang, the unofficial anthem of the Korean independence movement. Unlike the Okinawan main island, friendships between Miyako islanders and Koreans formed and many blossomed. But despite the absence of combat operations, Hong writes, the ianfu remained “captives forced by the politics of death into lives of confinement, misery, and despair” (p. 431).

Chapter 8 is the book’s nodal point, where lines of inquiry opened in Parts 1 and 2 converge to convey a broader but more nuanced, and often horrific, picture of the role the ianjo played in army sexual politics. Here, the author analyzes the military’s use of the comfort stations to inculcate a generalized phobia of military rape and a fear of survival. The militarization of the sex facilities worked to strengthen the army’s grip over its own forces and the civilian populace, which the military distrusted deeply but now depended on for its survival. Tomiyama’s review dwells on this point at some length.

This critical chapter concludes with a discussion of the post-combat phase of the invasion and the ensuing U.S. military occupation. The militarization of Okinawa did not end with the collapse of the Japanese 32nd Army in late June 1945 but actually accelerated, a process that has continued into the present. With the invasion still in progress, American forces rounded up non-combatants, placed them in internment camps, and confiscated great swaths of private land, enabling them to expand former Japanese bases and build new ones for a projected assault on Kyushu and the home islands.

On Okinawa Main Island, the highly organized military prostitution of the comfort stations was replaced immediately by the spontaneous sexual assaults of U.S. infantrymen as they fanned out across the land. Of particular note is Hong’s discussion of GI rapes in temporary internment camps and the fate of Korean ianfu and Okinawan juri in the refugee control areas of the north. The menace of sexual molestation, she emphasizes, extended beyond the era of direct U.S. military rule, persisting to this day.

In her epilogue, Hong visualizes a new epistemology of war and sexual violence that is based not only on the experiences of the victims but also on those of bystanders obliged to witness their suffering. That collateral trauma, the author tells us, informs many war memories and offers Okinawans an exceptionally “productive space” for reflecting on what Tomiyama’s review calls their “exceptionalized” subject position in Japanese society today. Through this cumulative process, an endogenous consciousness is gradually being reconstituted from a variety of wartime and postwar collective experiences and memories. In his review, Tomiyama terms this heightened self-awareness the “new communal” and concurs with Hong that memories of the battlefield are its point of departure.

A concluding essay in the guise of an appendix serves as a metasynthesis of the Okinawan war’s wider historical ramifications for East Asia. It includes a comprehensive but tightly argued geneological reflection on South Korea’s “discovery” of the Ryūkyūs in the 1980s, as that nation transitioned to democracy, and examines the significance of the Battle of Okinawa for contemporary Okinawan and Korean postcolonial reassessments.

A Personal Note

As translator/editor, I found Hong’s writing to be understated, deeply intuitive, full of subplots and other surprises, and reminiscent of a shrewdly constructed police procedural—one that commands the reader’s interest but also demands close attention to myriad historical, cultural, and military details. The book is a hybrid creation that draws on four languages (Okinawan, Japanese, Korean, and English). It is equal parts travelogue, gazetteer, local history, ethnography, army field manual, battlefield reportage, and war memoir, all woven into a coherent whole by survivor narratives and the author’s cogent multidisciplinary analysis of war, sexual violence, and historical memory.

Many of Hong’s arguments begin as seemingly casual observations around which empirical evidence is allowed to accumulate over a span of several chapters. Although the progression from point A to point B is not always a straight line, frequently doubling back on itself, her insights move ever upward, drawing the reader with her in a slowly widening spiral whose final resolution does not come into full focus until the final chapters of the book. For me, the vistas offered are revelatory and sobering and well worth the rigors of this deep dive into “a multifaceted Okinawa with many names” (p. 498). Tomiyama’s review is an indispensable guide for those who would accompany Hong on her difficult but rewarding journey.

I wish to express my gratitude to Brill for allowing us to publish the maps and figures reproduced here. I am also grateful to Kurt Radtke, Professor Emeritus of Leiden University, and to Norimatsu Oka Satoko and Mark Selden of The Asia-Pacific Journal for their insightful editorial comments.

When Violence is No Longer Just Somebody Else’s Pain

Tomiyama Ichirō

Brill’s 2020 publication of Hong Yunshin’s “Comfort Stations” as Remembered by Okinawans during World War II is a welcome opportunity to reassess the book’s contributions to our understanding of the military abuse of women in armed conflicts. The English version updates the author’s original 2016 study of the Japanese army’s sexual politics during its occupation of Okinawa (1944–45) and renews Hong’s clarion call for an experience-based methodology capable of elucidating the imbricated spheres of sexual and colonial violence that produced Japan’s “comfort women” system during the Asia-Pacific War (1931–45).

Since Hong’s 500-page tome first appeared in 2016, it has attracted attention in Japan proper but tellingly has been read in Okinawa with particular enthusiasm. The Okinawa Times immediately selected the volume for its 2016 Annual Book Award. Reviewers generally highlight the author’s novel postcolonial approach to the comfort women (ianfu) issue. As the title indicates, Hong foregrounds military “comfort stations” (ianjo) rather than the ianfu themselves, distancing her analysis from binary aggressor/victim models and the “dividing practices” of nationality, race, and ethnicity (Hong 2020: 5, 10). Instead, she plumbs Okinawan memories of the ianjo and their political and socio-psychic impacts on village life as the imperial army progressively weaponized the sex venues in the runup to the Battle of Okinawa (late March to late June 1945). These retrospections on war are antithetical to state-sponsored national war remembrances, and the author reads in them “a conflicted but resilient and resistant Okinawan alterity” (p. 2), one that transgresses ethnic and national boundaries and questions the oft-asserted unity of the Japanese nation-state.

Okinawa is an anomaly in the administrative and political structure of the modern Japanese state. The southern Ryūkyūs were forcibly integrated into Japan proper in 1879. But as Hong emphasizes, despite its legal status as a prefecture, Okinawa was not a wholly Japanese internal territory (naichi = Inner Japan). Nor was it a fully colonized external territory (gaichi = Outer Japan), such as Korea or Taiwan. Okinawans were caught somewhere in between. During the Pacific War (1941–45), the prefecture was the only part of Inner Japan forced to accept a full-scale military occupation replete with large numbers of comfort stations and to suffer a major land battle and quasi-permanent occupation by a foreign adversary. Through the ianjo and their Korean inmates, Hong notes, many islanders could glimpse their own borderline standing in the imperial order. Contemporary self-reflections on that status, she says, are part of a postcolonial reckoning that today is reimagining an Okinawan, as opposed to a Japanese, community.

Hong’s book is structured around survivor interviews and life histories, but those narrative elements are corroborated and enhanced by an array of primary sources that include military battle logs (jinchu nisshi), periodic unit publications, army field maps, war diaries, postwar memoirs, and extensive archival documents. In her quest to grasp the internal dynamics of militarization and systemic sexual brutality, Hong combines the perspectives of oral history, ethnography, social history, gender studies, political science, international relations, psychology, and sociology. That interdisciplinary mix produces a surfeit of empirical detail and a profusion of converging themes and subtexts that are complex and not easily summarized. Here, I confine my remarks to those aspects of the author’s work that coincide with, and continue to enrich, my own research. I begin by situating Hong’s book in the context of postwar Okinawa-Japan relations as reflected in the so-called comfort women issue.15

1. Okinawa, Japan and the Comfort Women Question (1975–91)

In August 1991, Kim Hak-sun (1924–97) became the first ianfu survivor in South Korea to speak publicly about her wartime ordeal as a comfort woman. Her revelations and subsequent lawsuit16 became the first of many revendications that eventually embroiled Tokyo and Seoul in a diplomatic feud over Japan’s refusal to accept full moral and legal accountability for the comfort women system. Kim’s demands for redress initially resonated with the Japanese public, and academics, political leaders, social critics, and journalists took note. Despite their divergent views on the issue, commentators appeared to agree on at least one point: a need to cite South Korean survivor testimonies to bolster their arguments. In so doing, however, they ignored the ianfu of many other ethnic and national origins.17

Hong points out that despite the Japanese legal system’s formal commitment to impartiality, the courts are not immune from Japan’s postwar culture of historical denial, which has perpetuated a “colonialist and misogynist discourse” that downplays the imperialist and wartime past. This, she says, “is the real issue that survivor-plaintiffs confront every time they take the witness stand” (p. 444). Despite that implicit bias, for some 20 years, former comfort women continued to appear in court to refute the bad-faith questions of the conservative media and historical revisionists: “Was coercion involved?” “Were you really sex slaves, or just prostitutes?” “Can you prove it?” In one sense, the author writes, it was as if society had set up a figurative witness box from which the dramas of the women’s disputed victimhood could be reenacted for a skeptical public, whose minds seemed already made up (pp. 444–46).

This observation redounds to Japanese society’s current aversion to historical truth. It magnifies the courage of ianfu plaintiffs, their enormous achievements, and the contributions of lawyers, researchers, and human rights activists who have advocated for a meaningful official apology and state reparations. The suits litigated by former comfort women between 1991 and 2010 have been instrumental in documenting the harms they endured during the war and exposing the complicity of the wartime government and imperial military in creating, operating and expanding the ianfu system. Unlike many researchers, however, Hong does not use these testimonies to buttress her arguments. She focuses rather on the postwar remembrances of those who witnessed the ianjo in everyday life.

In the year leading up to the massive U.S. ground assault of April 1, 1945, Okinawans struggled to cope with the enormous social dislocations caused by the Japanese 32nd Army’s usurpation of their prefecture: extensive land expropriations, the billeting of soldiers in private dwellings, the seizure of family residences for comfort stations, compulsory food deliveries, quasi-obligatory sympathy visits to the troops, forced labor drafts, and the mobilization of able-bodied men and women, including school children, as military volunteers. Amid those tribulations, many villgers eventually came to feel a stronger affinity for the Korean women they met only occasionally than for the arrogant mainland soldiers (yūgun, “our boys”) who had commandeered their homes and occupied their communities. The originality of this book is the author’s search for traces of that affect in the postwar recollections of war survivors and its implications for Okinawan society today.

Although Hong prefaces her work with the brash disclaimer “These pages do not emphasize the personal stories of the ianfu” (p. 2), she makes a singular exception for Bae Pong-i (1914–91), one of only two Korean comfort women cited by name in the text. Although Bae makes cameo appearances in seven chapters, including the introduction and appendix, her story is never fully told. It is rather her liminal quality that the author accentuates here, using it to subtly frame the deep narrative structure of this volume by tacitly contrasting the contemporary Okinawan response to the comfort women with that of the Japanese public in the home islands.

In early 1975, Bae was the first Korean to be confirmed as a former ianfu in Okinawa. She had been found living there nearly three years after the territory’s return to Japan from American control in 1972. Deceived by a Japanese procurer (zegen) in Korea and trafficked to Okinawa in October 1944, Bae was unable to return to her divided homeland after the war and subsisted quietly under the radar of local officialdom and the U.S. military government. When Okinawa was returned to mainland Japan in 1972, resident Koreans in Okinawa became subject to Japan’s Alien Registration Law. Following Bae’s apparition in 1975, she was given the choice of registering as a foreigner or being deported to South Korea.

Okinawans greeted Bae’s sudden manifestation with surprise and a prick of conscience, just as many Japanese would be stunned initially to discover the existence of Kim Hak-sun some 16 years later. The first media reports referred to Bae as “Person A” to protect her privacy. Pressured by local residents, prefectural authorities quickly granted her an alien residence permit, allowing her to remain in the prefecture. Her presence spurred Okinawan municipal history offices, scholars, and local researchers to query war survivors about other comfort women, and they began recording those stories and pinpointing the erstwhile locations of military sex venues. From the 1970s to the early 1990s, that concerted effort produced valuable information on the ianfu and a detailed map of Okinawa’s comfort stations. Compiled in 1992 by the Okinawan Women’s Research Group and published in 1994, the map identified 130 former ianjo sites (by 2012, a total of 146 had been verified).

In the Japanese home islands, Bae’s discovery in Okinawa was generally met with polite indifference.18 The ianfu would not become a major social issue there until Kim Hak-sun stepped forward in the summer of 1991.19 Thus, in the late 1970s and 1980s, no chorus of protest was raised in Tokyo about Bae’s wartime experiences. Few tried to imagine what hardships she might have endured in postwar Okinawa, where until 1972, people lived in the shadow of the American occupation and its military bases, absent the basic civil and political liberties guaranteed by Japan’s 1947 constitution.20

Conversely, in Tokyo, Osaka, and other large mainland cities, Kim Hak-sun’s later disclosures spurred women’s rights advocates to action. Together with the South Korean women’s movement, they launched a transnational civil society campaign that backed the demands of ianfu survivors for justice and spread quickly to other Asian countries. With the support of UN human rights bodies, the resulting groundswell of grassroots activism would culminate in the Women’s International War Crimes Tribunal on Japan’s Military Sexual Slavery. Convened in Tokyo in December 2000, the tribunal signaled the high point of the redress movement.21

Mainland Japan’s long silence about the comfort women of Okinawa holds an important lesson for all who have grappled with this issue. Hong suggests that the 16-year gap separating the emergence of Bae Bong-i in Okinawa and Kim Hak-sun in Seoul and Tokyo separates two disparate approaches to understanding and addressing the ianfu issue. The first is the introspection and local truth-finding that Okinawans engaged in from the late 1970s. The second is the view from Tokyo, where since 1991, a civil society movement has championed a determined but narrowly focused crusade for social justice that has sometimes seemed aloof from what was happening in Okinawa. Hong’s perceptive referencing of that epistemic disconnect emerges gradually, often inductively, but constitutes an underlying structural element of her narrative.

2. Comfort Stations and the “Politics of Death”

Hong’s stated aim is to understand how the proximity of comfort stations “affected the Okinawan consciousness,” thereby altering the rural world “in ways both subtle and profound” (p. 1). The ianjo, she concludes, were “an embodiment of the violence underpinning the military institution, male sexual ‘prerogative,’ and ethnic oppression. Okinawans as witnesses to the sex facilities are the counterpoint that brings these forces into focus” (p. 2).

Using the 1992 comfort station chart, the author has carefully superimposed ianjo sites on army field maps, showing the venues to be clustered around military airfields and troop emplacements on each of the prefecture’s major islands (Map 2). It is estimated that the women prostituted there were largely Koreans, with smaller contingents of indentured Okinawan women (juri) from Naha’s licensed quarter in Tsuji and a scattering of Taiwanese and mainland Japanese.

Many of the personal accounts Hong introduces convey an almost electric sense of urgency, evincing the primal terror that military imperatives and war propaganda instilled in civilians. That trepidation seeped into every pore of Okinawan society. “The psychological trauma and disorientation experienced by war survivors did not spring from ethnic differences—from the fact of being “Japananse,” “Korean,” or “Okinawan,” Hong writes. Rather, their source was “a pathologically obsessive fear implanted by military propaganda. This pathology was rooted not only in a visceral premonition of annihilation in a land war but also, paradoxically, in a horror of surviving that cataclysm” (p. 9).

For this reason, while Hong recognizes the ethnic and national differences that divided Okinawans, Koreans, and Japanese, she does not privilege them. She centers instead the experiences of beleaguered war survivors, “the disturbed, the hesitant, the indecisive …” (p. 10), all burdened by searing memories of the combat zone and the gut-wrenching dread that convulsed it. It is these quiet striken voices, erased by Japan’s postwar historical amnesia, that Hong attempts to reacquaint us with in order to, as I have put it elsewhere, “create an imagination for wounds that cannot even become testimony.”22

I believe Hong is describing the following process. Everyone on the field of battle becomes transfixed by the sudden realization that what is happening to others nearby is no longer just “their problem.” That shock of recognition springs from dismay, even panic, that one is on the verge of dying a meaningless, painful death. People tend to dismiss random acts of aggression as something that happens to others, but such rationalizations cloak what French philosopher and social theorist Michel Foucault calls the “politics of death.” While most of us are convinced that “it can’t happen to me,” the battleground tolerates no such conceits. There, the raw bodily fear that permeates the killing fields is shared: it is mine, it is yours, and it is both of ours at the same time, despite the differences that separate us.23

Hong hunts for clues to the genesis of that terror in the postwar reminiscences of Okinawans with firsthand knowledge of the comfort stations. In those accounts she discerns an intuited connection between what was happening to the ianfu and what was happening to Okinawans. For instance, when Bae Pong-i surfaced 30 years after the end of the war, instead of adopting her as a cause celebre and inviting her to speak at rallies, Okinawans recalled the comfort stations, the women forced to live there, and their own nightmarish apprehensions. Hong views that nascent sense of connection, which she calls a “relational space” (pp. 27–28) as a latent prospect that has inscribed itself in Okinawa’s modern experience of war and is, she believes, important for the postwar construction of a distinctively Okinawan worldview. Like many of her discoveries, that epiphany emerges unobtrusively as a subtext to the main narrative but remains one of the book’s important findings.

In her analysis of war anxieties, the author details the ways in which militarization in its various shapes insinuated itself deep in the interstices of daily living, transforming the village world into a battlefield from within. Here, she acknowledges her intellectual debt to Foucault and his concept of the politics of death (thanatopolitics), which, she writes, “lies in wait in the hidden war zones of the everyday world” and constitutes the dark underbelly of biopolitics and biopower (p. 5). In the Battle of Okinawa, the coercive force emanating from military sex venues became a structural feature of army thanatopolitics. Building on Foucault’s theory of biopower, Achille Mbembe, reconfigures that term as “necropolitics,”24 which I use below as synonymous with the politics of death.

Okinawan researchers have shown that in the year between April 1944 and March 1945, comfort stations were established in every corner of the prefecture. The army located roughly half of those facilities in private homes requisitioned from Okinawans, often on village outskirts. With some frequency, however, sex venues were also found in public spaces, including village shrines, schoolhouses, fairgrounds, sporting arenas, Japanese-style restaurants, and even bustling commercial districts. The prominent display of ianjo at the major intersections of rural life proclaimed at every turn the army’s mastery over the bodies of interned women and, by extension, over those of Okinawans, as well. The comfort stations were a kind of psychological force multiplier that amplified the army’s sexual politics, spreading its fearsome message of despair far and wide.

Fig. 2: The Okiku Japanese restaurant: a comfort station for kamikaze pilots, Kina hamlet. Painting by Miyahira Ryōshū. Courtesy Yuntanza Museum, Yomitan village.25

Okinawans looked askance at the ianjo, but they did not remain passive observers for long. The prefecture’s quasi-colonial existence at the southern extremity of the Japanese homeland had assigned them a preordained role as sacrificial pawns (sute-ishi) in a fight without quarter. The Japanese high command knew that the battle could only be prolonged, never won. As the threat of invasion intensified, the aura of physical violence that enveloped the comfort venues fed a growing presentiment of death.26 Civilians were trapped between a desperate Japanese garrison, outgunned, outmanned, and steeled to die fighting, on the one hand, and “bestial hordes” of heavily armed and well-fed foreign troops supported by a supply chain that spanned the Pacific, on the other. Just as the comfort women did, ordinary Okinawans found themselves locked in a hopeless dilemma.

As the ground war loomed, imperial troops began executing large numbers of Okinawan non-combatants for infractions of military rules, imagined disrespect, suspected disaffection, purported spying, and from early April 1945, with the start of the Allied ground offensive, speaking their native tongue, Uchinaaguchi. For the military, this policy of intimidation was part of a strategy of total battlefield mobilization and control. Behind the allegation of “spy,” wielded for the slightest deviance from military orders, was an unforgiveable moral offense: the refusal to abandon Okinawan ways and assimilate, i.e., a dereliction of the duty to become “Japanese.”27

At the same time, army propaganda fostered a horror of American atrocities, warning that when the battle began, women would be raped and men castrated. Those images had been fine-tuned by the tales of Japanese sexual atrocities that Okinawan veterans brought home from the war in China (1937–45). Military comfort stations, the army warned, were just one example of what local women could expect when enemy forces landed. By early 1945, Hong writes, the presence of comfort women in the villages had come to “evoke a phobia of captivity and sexual subjugation that could … border on madness” (p. 341). Surrender became unimaginable for women and men alike, and when the army ordered the population to die fighting or kill themselves singly or in groups, many families and even entire villages tragically complied. To imperial soldiers preparing for death, the notion that civilians might outlive them was intolerable. In many instances, they handed out grenades, one per family, and then abandoned the villagers to their fate.

It is important to note, however, that as it became clear that the Japanese army was losing ground, many islanders ignored the risks and spoke in Okinawan, sang traditional folksongs, voiced their resentment of the military to friends, and encouraged each other to forget suicide and survive for Okinawa’s sake. That discourse of resistance, born on the battlefield, was a spontaneous rejection of the violence of “foreclosure” (see below), and it gave rise to a budding consciousness of belonging to the Okinawan people rather than the imperial state.28 Here, Hong’s concerns dovetail with my own.

3. Witness to Violence

In the English version of her book, the author introduces the seminal work of Annmaria Shimabuku,29 who shares a similar conceptual awareness. Shimabuku, for instance, uses the term “alegal” to describe Okinawa as a territory that is “unintelligible” to the law of the sovereign state that has subsumed it, and whose social existence presupposes a “censoring violence” that is endemic. That world is not the product of a politics rooted in systems of laws and institutions. Rather, its maintenance is predicated on the territory’s preemptive exclusion from the realm of the political.

As Shimabuku points out, this prohibitive act constitutes the precondition of normal social life, which is sustained only by the perpetual “censorship, exclusion, and exception of a life force that has always already been there.”30 Judith Butler borrows the psychoanalytic concept of foreclosure to describe what amounts to a process that I call violent “exceptionalization.”31 Although neither Hong nor Shimabuku employ the term foreclosure, I make use of it below, as I have in my other writings.32

In her discussion of language and censorship, Butler notes that the act of exclusion also determines the realm of permissible speech, which she defines as “the domain of the sayable,” or “the conditions of intelligibility.” Formulated by power, this circumscribed domain authorizes not so much what can be said as who can say it, no questions asked—a mechanism that “operates to make certain kinds of citizens possible and others impossible.”33 When the outlawed attempt to explain themselves to authority, they often “move outside the domain of speakability.” Not only are their words suddenly incomprehensible, but transgressing that boundary with their unintelligible truths may put their very survival as subjects at risk. That shutdown generates presentiments of a more fundamental terror: that of losing one’s tenuous place in the biopolitical hierarchy and being singled out for extreme sanction.34

Hong and Shimabuku depart from conventional studies of biopolitics by foregoing an analysis of concrete power relations. Both strive instead to identify in their research the possibilities of a historical consciousness such as might allow an exceptionalized people confined in a foreclosed territory to live peacefully together despite the structural forces binding them to a superordinate nation-state. Here, such people are those who, together with their territory, have been swallowed whole by a larger national entity without fully recognizing, or being fully recognized by, the sovereign power.35

Hong studies the Battle of Okinawa, where Okinawans, Koreans, Japanese, and Americans clashed tragically in the bloody and tormented but “productive and diversified social space” of the battlefield (p. 11). Her goal is not to pass historical judgements on the actors, but to sketch a genealogy of violence that can make sense of the throbbing but “seemingly inexplicable fear that suffused the war zone” (p. 502), where ordinary people became “both executioner and victim at the same time,” leaving them to wonder after the war “what it was that had pushed them to such [violent] extremes” (p. 343). Studies of state power, race, ethnicity, class, and gender are less useful here, the author cautions. Earlier, she cites Okinawan sociologist Nomura Kōya, who wrote that “if [powerful people] had not turned Okinawa into a charnel ground […] I would not have to worry about the Battle of Okinawa.” “But some Japanese killed Okinawans,” he explains. “And some Okinawans killed other Okinawans.” “Those Okinawans,” he says, “are me. Japanese killed me. I killed Okinawans, I killed Koreans.”36

Hong’s point of departure is the comfort station as a nexus of military sexual coercion, but her primary interest is postwar Okinawan reflections on that violence. The author notes that when the 32nd Army began setting up ianjo in the spring of 1944, the prefectural governor, Izumi Shuki, refused to help it recruit juri from Naha’s licensed quarter. “This is not Manchuria or the South Seas,” he told the army. “In any event, Okinawa is imperial soil. You cannot build that sort of facility [here]” (p. 86). To Izumi, a former Home Ministry official from the main islands, the scandal of building military sex venues on the sacred soil of the homeland was a question of principle: comfort stations belonged in colonies and occupied territories, not in Inner Japan, where they were sure to “corrupt public morals.” “Has the emperor’s army no pride?” he admonished (p. 87). To Okinawans, writes Hong, the ianjo were something else altogether: an unmistakable confirmation of their subservient status. As military sex facilities suddenly materialized in their towns and villages, many felt “a stab of humiliation” (p. 87), even betrayal.

The above episode reveals something fundamental about the differing self-perceptions of Okinawans and mainlanders. As I see it, for Okinawans, the stigma of second-class citizenship rankled, although many paid lip service to the official government line, hiding their resentment by feigning indifference. Japanese, however, viewed Okinawa through a one-dimensional filter. The prefecture’s administrative incorporation into the Japanese homeland disguised the fact that the government actually regarded it as a “quasi-colonial backwater,” which it was free to exploit as it pleased (p. 21). Most in the home islands could not acknowledge the prefecture for what it was: a de facto internal colony.

Today, a similar outlook taints mainland attitudes toward Okinawa, allowing the central government to impose policies on the prefecture that would be unimaginable anywhere else in Inner Japan.37 That double standard enables many to ignore the violence that is endemic to U.S. bases in Okinawa. What happens on Japan’s southern periphery, they believe, is not their affair. Such duplicity goes to the heart of the structural discrimination that characterizes the Okinawa-mainland relationship. How can a modern state as equalitarian in appearances as Japan refuse to address the unresolved injustices of the Okinawan war, the comfort stations, and the continuing U.S. military presence? Those problems share a common root: the perpetual foreclosure of the southern Ryūkyūs.

Although I refer to Okinawa as an internal colony, I do not wish to insist further on the analogy by suggesting that the prefecture is a colony in the literal sense, despite its origins in Meiji-era colonization practices. A “correct” theoretical model of colony-making is not helpful here. Confronting mainlander double-think about Okinawa requires something more radical, a new paradigm that can deconstruct and critique the everyday violence that sustains such an outlook.

Hong suggests that Okinawan contemplations of the war years and the sexual violence islanders observed constitute potential building blocks for an experiential epistemology of war (pp. 27, 447-50). Therein, she posits, lies the potential for a historical awakening that can lay bare “the dark underbelly” of necropolitics, liberating both Japanese and Okinawans from the corrosive practices of national self-deception.

Here, I would add some personal observations on the centrality of violence to “ordinary” social existence. To make sense of the world and our place in it, I believe that we must cultivate a critical attentiveness to the forms and gradations of the disorderly coercive forces that appear to surface randomly in the day-to-day world. Only in that way will we be prepared to sound the alarm before they can manifest as overt acts of aggression against specific groups of people.38 The secret is to recognize that, historically and socially, the erasure of prohibited Others is not just “their problem” but more fundamentally our own. In the present nation-state system, the hidden preemption of any part of society becomes an unconscious but formative element of majoritarian personal and social identities. To paraphrase Butler (n15), in the case of Japan, it is the act of exceptionalizing Okinawa as the irreducible Other that makes possible the formation of a stable Japanese subject.

We perceive that psychic rupture as natural rather than intimidating, in part because so many are its beneficiaries rather than its victims, who have been rendered socially invisible. The culturally encoded attitudes and values mobilized in support of that consciousness are fluid, layered, and mutually reinforcing. They reproduce the familiar cadences of daily existence that most take for granted but which the socially and politically marginalized experience as menacing and oppressive. It is that fear and the attempt to escape its clutches that drives the “minoritized” to seek conformity with the norm by destroying the “not normal” inner self—i.e., in the case of Okinawans, by striving to become “Japanese.”39 Refusing to acknowledge that dynamic is to be complicit in the quotidian violence that normalizes daily life for the many by excluding the exceptionalized few.

4. A Countervailing Narrative and Sites of Remembrance and Resistance

The efforts expended by Okinawans in the 1970s and 1980s to summon and reassess their empathetic memories of ianfu generated an outpouring of oral and written reflections. Hong writes that where comfort women are mentioned, it is often in the context of doubts about the war itself, lingering feelings of personal responsibility, and Okinawa’s fringe position in the greater society. Survivors have continued to publish their war experiences in autobiographies, local gazetteers, school chronicles, and multi-tome village, town, city, and prefectural histories.

Hong’s meticulous reading of that archive and her numerous personal interviews would have been impossible without this collective soul-searching. In my opinion, her tracking of the steady escalation of military coercion as seen by the witnesses to wartime sexual violence is an integral part of what the author calls “the grassroots process of war remembrance and reconciliation” (pp. 32–33: n45).

In fact, Hong worked with local governments to collect oral war histories in Nago City (Okinawa Main Island) and Miyakojima and was a member of the transnational team of Korean, Okinawan, and Japanese researchers who collaborated with local war survivors and citizens groups on Miyakojima to create the Memorial to All Comfort Women in 2008 (pp. 33, 441, 485). The author also finds in these fraught survivor narratives “a countervailing discourse” capable of confronting Japanese society’s refusal to account for the historical wrongdoing that “continues to stifle the voices of war victims” (p. 448). Her work in itself is an example of what such a counter argument might look like as it explores the many guises assumed by military sexual aggression and its social impacts.

Fig. 3: The Memorial to All Comfort Women, Miyakojima40

Hong remarks that the army was at pains to justify the construction of comfort stations, insisting that they protected “proper” young women by providing imperial troops with an authorized outlet for sex.41 Japanese soldiers were told, and most believed, that the comfort women were “gifts” from a beneficent emperor. But the venues staffed by colonial ianfu and identured juri were upheld by overlapping spheres of sexual, ethnic, and colonial oppression. Those concatenating forces were unleashed into the Okinawan life world as the army stripped the women it impressed into servitude of their ordinary social identities, reducing them to sexually and ethnically objectified cagtegories. Both ianfu and juri were excluded from basic social protections, including the “normal state of law,” thereby creating two distinct groups of women in society: those who merited the protection of the law and a minority who were “not normal” and thus were regarded as existing outside the law.42

The militarized bondage of the comfort venues debased colonial women, as seen in the widespread use of the ethnic slur Chōsen pī (“Korean cunts”), the army’s generic term for Korean ianfu. At the same time, that subjection implicitly banished the “nameless, fallen women of Tsuji” from the Okinawan ethno-body and communal fold (p. 93). The extreme duress of the ianjo melded with the mysogeny, partiarchy, and colonial and semi-colonial oppression that had been implanted in Okinawan life by the foundational act of exclusion.43

Military sexual politics did not dissipate with the defeat of the 32nd Army in late June 1945, or with Tokyo’s acceptance of the Allied surrender terms on August 15, or with the formal capitulation of outlying imperial forces in the Ryūkyūs on September 7. Of course, the comfort women system itself disappeared when surviving ianfu and juri were taken into American custody and detained in civilian relocation centers. For Okinawans in general, the “postwar era” began the moment they entered the camps. But for women—Korean and Okinawan, “protected” and “unprotected”—predators stalked them even there as GI rapes grew rampant. Interned women were also assaulted regularly by roving bands of Okinawan and Japanese guerrillas in the north, remnants of the 32nd Army, until their rendition in early 1947.

In 1949, the persistence of American sexual assaults forced a group of prominent Okinawan women who remembered the ianjo and had experienced the rape phobia of the early postwar camps to invite the intervention of Okinawan civil authorites. At their insistence, the governor of Okinawa petitioned the ruling U.S. military government to authorize and regulate commercialized prostitution in the form of dance halls. These were to be set up in specially designated entertainment zones. In his petition, Governor Shikiya Kōshin wrote: “I propose that the military government seriously consider establishing comfort facilities for military personnel (gun-in ian-shisetsu) and entreat you to implement this proposal with the greatest urgence” (p. 380).

In a particularly poignant passage in Chapter 8, Hong makes the following observation:

Looking at Okinawa’s military comfort stations … one is struck by a cruel irony. In both wartime and postwar occupations, the military usurped and transformed the traditional village world. To deal with those changes, Okinawans were obliged to collaborate, becoming unwilling accomplices in their own victimization. That “complicity” is perhaps the bitterest remembrance of all. Memories of being targeted as spies by “our boys” on the battleground merged with the phobia of being raped and brutalized by the American invader, and later occupier. Those wartime and early postwar traumas continue to haunt Okinawans today under an oppressive base system that has prolonged their anguish. Recollections of the women from Korea who were confined in Okinawa’s comfort stations are also invoked frequently (p. 383).

Jahana Naomi, an editor for the Okinawa Times, quoted the above passage in her commentary on a recent talk by Hong.44 Jahana notes that until the 1990s, Okinawans generally did not discuss in public the comfort stations and postwar sexual predation by American troops. Two events changed that, she says. The first was the creation of the comfort station map in 1992, the second was the abduction, beating, and rape of an Okinawan girl by three U.S. military personnel in September 1995 and a survey of American sex offenses released six months later, in early 1996, by Takazato Suzuyo and others, all of whom had collaborated on the 1992 map.45 At last, Okinawans could see that military sex crimes had been a continuous issue in their islands for more than half a century, from the wartime ianjo of 1944–45 to the gang rape of a 12-year-old girl in 1995.

But something else in Hong’s talk enabled her to see that connection in a different light, Jahana said. For Hong, the comfort stations were not merely places of torment, where military sexual assaults daily produced endless victims and assailants, but symbols of physical control over which the specter of rape and death hovered, terrorizing entire communities. The important point, Jahana concludes, is that those venues were thrust brusquely into the everyday world of Okinawan life, opening a path through which the army could channel its politics of death into the general community as the land war approached.

Hong writes that, “The concept of battlefield violence must include not only people who were directly victimized by it, but also those forced to witness and … internalize it” (p. 450). In the life stories of the latter, she suggests, are to be found “the seeds of a future resistance” to contemporary strains of misogyny, racism, and nationalism (p. 343). In fact, the author points out that today many former comfort stations have become privileged sites of remembrance as Okinawans whose wartime homes were seized as ianjo have opened them to the public. There, they engage with younger generations, talking about the comfort women and exploring together the fundamental causes of the Okinawan war. When words fail, as they invariably do, young people are asked to try and imagine the chronic fear of molestation and physical annihilation that those places once embodied. Such memorial spaces, Hong says, “are also, potentially, sites of resistance” (p. 458), where young people are encouraged to rethink the official misrepresentations of the war and the comfort women.

5. After the Testimonies…

Where do we go from here? What lessons are we to draw from this book? At the risk of repeating myself, the malevolent force radiating from Okinawa’s military comfort stations was the reiteration on a smaller scale of the foundational violence that has marginalized Okinawan society since its annexation more than 140 years ago. The comfort women system as a whole was possible only because of an underlying system of sexual, colonial, and semi-colonial oppression. For those reasons, Hong suggests, not even a legally binding remediation agreement that is acceptable to former ianfu can truly resolve the comfort women issue.

The metaphorical witness box that society has reserved for the survivors of wartime sexual servitude is structured in such a way that the courts, the media, and the general public “hear” only those utterances that “an already decided field of language” permits them to hear.46 In other words, even before the plaintiffs mount the stand, their pre-censored statements are already barred from “the domain of the sayable” largely because of who they are: sexually enslaved war victims from former Japanese colonial and occupied territories. The women struggle mightily to change the biased perceptions of their audience, but since their words verge on the unintelligible, most listeners hear only that which confirms their preconceptions.

For the last 15 years, official government policy has been to deny publicly the use of military coercion in recruiting comfort women and to openly disparage ianfu as paid prostitutes and opportunistic camp followers.47 Feminist scholar Takemura Kazuko points out that once litigating survivors had finished giving evidence, they and their supporters were faced with two choices. They could either reconcile themselves to a testimony that was circumscribed and misconstrued or redouble their struggle against the greater iniquity of the state’s disavowel of war responsibility and its re-traumatization of former victims. In that context, Takemura suggests that the term “coming out” should be expressed in the present progressive tense—”to be in the process of coming out.”48 “Violence,” she writes, “does not express itself exclusively as violent behavior [with a clear beginning and end]. It never rests. Even after the event, it sinks its tentacles deep into the inner recesses where our life force resides.”49 As we work with others who share our concerns, each of us must acknowledge and deal with that baneful inner presence and strive to identify and extirpate it. In that sense, we are always engaged, always in the process of coming out.

Insisting on full legal restitution for the grievous wrongs done to the comfort women is the very least we can do as human beings. Over the last 30 years, the redress movement has worked hard to achieve just that. But such efforts are not enough. Each of us, regardless of gender identity or racial, ethnic, or national origins, can learn from the lives of former comfort women and Okinawan war survivors. If we are to change the world, the first step must be to expose the existence in our own backyards of those proscribed domains enfolded within the deeper violence that lurks, as Hong reminds us, “in the hidden war zones of the everyday world.”

When Bae Pong-i emerged suddenly in 1975, Okinawans did not ask her to take the witness stand. Instead, they revisited their personal memories of the captive women they had once seen in their villages and embraced their pain as part of their own, not somebody else’s. In the testimonies Hong analyzes, it is clear that Okinawan civilians, despite their dislike of the ianjo, sympathized with the Korean and Okinawan women confined there, realizing that they, too, might soon share a similar fate.

In that intuited relational space, villagers watched the sex venues even before they had words to properly describe them. They saw everything that happened in the vicinity. They noted with curiosity when small groups of comfort women hurried by on errands, or on their way to compulsory VD examinations. As nurses in local clinics, some helped administer those tests while engaging the women in idle conversation. Okinawans averted their eyes as they passed the double lines of soldiers queuing in front of the sex venues and heard the drunken laughter, coarse language, and wailing that escaped from inside. Occasionally, they shared red peppers, sweet potatoes, and other food items with the women from Korea and exchanged pleasantries at the local well. They observed the establishment of the ianjo in their communities, noted their relocation as Japanese defensive lines shifted abruptly, and witnessed their abandonment as the American invasion began. Finally, they confronted the necropolitics that seeped from those noxious sites, threatening to drown them all.

Buried in survivor retrospections, says Hong, is a long-suppressed history that survives today in Okinawan memories of military comfort stations and chance meetings with their occupants. As islanders remember that felt connection, they redirect their critical gaze inward to their own society, gauging the deeper meanings of those encounters. In so doing, they energize that relational space. The power of their reminiscences is transforming those points of reflection and convergence with the past into a contemporary platform from which Okinawa’s place in the Japanese political order can be reexamined and challenged.

This process is part of a larger historical moment that I call the “new communal.”50 Its unscripted discourse is grounded in the memories of the battlefield—sexual violence, spy hunts, Okinawans sacrificed as cannon fodder, civilian massacres, and military-induced group suicides—but also in the postwar struggles to recover stolen land and resources (tochi tōsō, shima-gurumi tōsō), achieve a base-free reversion, end U.S. military violence, and build a self-conscious and self-determining Okinawan community.51 This new mindfulness, which I am tempted to call an “All Okinawa” consciousness, represents the “totality of many diverse efforts”52 undertaken by Okinawans since the end of World War II to rethink their past and future in Okinawan terms. For the last several years, this movement has also been enriched by the creative relationships that Okinawans, once foreclosed by history, have forged not only among themselves but also with the Okinawan diaspora, and with other Pacific Islanders who have been dispossessed by the same sovereign powers, Japan and the United States, that now work in tandem to enforce the nation-state order at their expense.

To write a history that has been prohibited from the outset is to explore paths to a different future. Hong’s pioneering work on wartime sexual violence and postcolonial memory shows us a way forward.

“Comfort Stations” as Remembered by Okinawans during World War II was released by Brill, a venerable publishing house in the Netherlands. In the Afterword, the author expresses her admiration for Jan Ruff-O’Herne (1923–2019), a former Dutch POW and ianfu who died in August 2019. In 1992, Ruff-O’Herne broke nearly 50 years of silence when she went public with her wartime travails in Indonesia, becoming the first European survivor to openly support the struggle of Korean comfort women. That gesture of solidarity left a lasting impression on Hong, and her tribute to Ruff-O’Herne’s courage and lifework is also a parting message to the reader. It is this reviewer’s hope that the English edition will spread that message to a wider audience abroad. Hopefully, a new readership will continue the task begun here, as people in other parts of the world ask themselves which territories and groups in their own communal spaces have been preemptively disenfranchised and relegated to the social margins. It is my personal belief that reading this volume is to already participate in that collective endeavor.

Notes

Hong Yunshin, “Comfort Stations” as Remembered by Okinawans during World War II. Trans. Robert Ricketts (Leiden/Boston: Brill, 2020, 564 pages).

Ama yuu is the title of a collection of essays edited by Mori Yoshio, Tomiyama Ichirō, and Tobe Hideaki: Ama yuu e: Okinawa Sengo-shi no jiritsu ni mukete [Toward a Better World: For a Self-determining Postwar History of Okinawa] (Tokyo: Hosei University Press, 2017).

Tomiyama’s major works include Kindai Nihon shakai to “Okinawajin:” “Nihonjin” to naru toiu koto [Modern Japanese Society and “Okinawans”: What it Means to Become “Japanese”] (Tokyo: Nihon Keizai Hyōronsha, 1990); Senjō no kioku [Memories of the Battlefield]. Tokyo: Nihon Keizai Hyōronsha, 1995 (revised edition, 2006); Bōryoku no yokan: Ifa Fuyu ni okeru kiki no mondai [Presentiments of Violence: The Problem of Crisis in Ifa Fuyu’s Writings] (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 2002); Ryūchaku no shisō:“Okinawa mondai” no keifugaku [Contemplations of a Castaway: A Geneology of the “Okinawa Problem”](Tokyo: Inpakuto Shuppankai, 2013); and Hajimari no chi: Fanon no rinshō [Beginnings: Fanon, Clinically Situated] (Tokyo: Hōsei Daigaku Shuppanyoku, 2018). Since 2006, Tomiyama has also edited six volumes dealing with postcolonial memory, post-utopian anthropology, Okinawa’s modern historical experience, conflict and its resolution, military violence, and the construction of an autonomous Ryukyuan consciousness in postwar Okinawa.

In addition to the present volume, Hong’s work includes “Okinawa kara hirogaru sengo-shisō no kanōsei: Senjō ni okeru josei no taiken o tsūjite” [The Possibilities of an Emergent Postwar Thought Proper to Okinawa: The Experiences of Women on the Battlefield]. Ōgoshi Aiko, Igeta Midori, eds., Sengo, bōryoku, jendā I: Sengoshisō no poritikkusu [The Postwar Era, Violence, and Gender, I: The Politics of Postwar Thought in Japan] (Tokyo: Seikyūsha, 2005); Hong Yunshin, ed., Senjō no Miyakojima to “ianjo”: 12 no kotoba ga kizamu “josei-tachi e” [The “Comfort Stations” of Miyakojima in the Okinawan War: “To the Women,” a Memorial Engraved in 12 Languages] (Naha: Nanyo Bunko, 2009); “Kakko-tsuki no kotoba-tachi e: Miyakojima, sono “ishitsu” no Okinawasen kara no toikake [To the Little Words in Quotation Marks: Problematizing Miyakojima and its “anomalous” experience in the Battle of Okinawa]. Ōgoshi Aiko, Igeta Midori, eds., Sengo, bōryoku, jendā III: Gendai feminizumu no eshikkusu [The Postwar Era, Violence, and Gender, III: Modern Feminism and Ethics] (Tokyo: Seikyūsha, 2010); “‘Nikkan kankeishi’ no shūhen: Chōsen to Ryūkyū, ‘Chizujō’ ni egakareru kankeishi” [On the Pheriphery of Japanese-Korean Relations: Korea and the Ryūkyūs, a Relationship that can be “Traced on a Map”]. Ajia Taiheiyō Tōken (Journal of Asia-Pacific Studies), Waseda Institute of Asia-Pacific Studies, No. 20, 2013; and “Nago/Yanbaru ni okeru Nihongun ‘ianjo’” [Japanese Military “Comfort Stations” in Nago and Yanbaru]. Nago City History Editorial Committee, ed., Nagoshi Honhen 3: Nago/Yanbaru no Okinawasen [The History of Nago City, Vol. 3: The Battle of Okinawa in Nago and Yanbaru], (Nago: Nago City, 2016).

Hong Yunshin, “‘Tomadou ningen’ no tame no anzen hoshō: Okinawa to Kankoku ni okeru hankichi-undō ‘jūmin akutā’ no shiten kara” [Human Security for Overwhelmed War Survivors: Anti-base Citizens’ Movements in Okinawa and Korea]. Master’s Thesis, Waseda University, March 2004. This was published under the same title in the periodical Josei, sensō, jinken [Women, War, and Human Rights], July 2005, pp. 53–93.

“Okinawasen-ka no Chōsenjin to ‘sei/sei’ no poritikusu: Kioku no ba toshite no ‘ianjo’.” Ph.D. Dissertation, Waseda University, 2012.

In Japanese, the military euphemisms “comfort women” (ianfu) and “comfort stations” (ianjo), coined in 1932 by imperial armed forces in Shanghai, are frequently enclosed in parentheses to remind the reader that the terms are problematic. To reduce redundancy, I follow English-language academic convention and forego that emphasis after first usage.

In 1872, four years after its creation in 1868, the Meiji state forcibly annexed the Ryūkyū Kingdom (1429–1879) on Japan’s southern periphery and, in 1879, integrated it into Japan’s national administrative grid as Okinawa Prefecture. Three years later, the government incorporated the Ainu homeland (Ainu Moshir) in the north into the home islands as Hokkaido (1882). Following the Sino-Japanese (1894–95) and Russo-Japanese (1904–05) wars, Japan extended this colonial empire by annexing Taiwan (1895) and Korea (1910). The latter were declared external territories (gaichi), and their inhabitants were forced to become imperial subjects—Japanese nationals second class. Following the outbreak of World War I in 1914, the Japanese state added the former German mandates in the Pacific to its overseas domain. In 1932, the imperial military occupied parts of Shanghai, where it set up the first comfort stations,* and established the puppet state of Manchukuo in northeastern China (Manchuria), which it had invaded in the autumn of 1931. Five years later, in 1937, it launched a full-scale invasion of China. Japan’s attacks on Southeast Asia and the United States in early December 1941 marked the beginning of the so-called Pacific War (1941–45).

* Regarding the Shanghai comfort stations and the origins of the comfort women system, see The Digital Museum: The Comfort Women and the Asian Women’s Fund (2007), available online. This site is a collection of military archival documents published by the Japanese government and is available in Japanese, Korean, and English.

Source: Bōeichō Bōeikenkyūjo Senshishitsu [War History Office, National Institute for Defense Studies, National Defense Agency]. Senshi sōsho (11): Okinawa hōmen Rikugun sakusen [War History Series no. 11: Japanese Army Operations around Okinawa]. Tokyo: Asagumo Shimbunsha, 1968, p. 22. Hong 2020: p. 45.

Source: Yōsai Kenchiku Kinmu Dai-roku Chūtai. Jinchū nisshi [Sixth Fortress Construction Duty Company. Staff activity report], June 4, 1944. Hong 2020: p. 122.

Comfort stations generally followed combat units as the latter were redeployed south in late 1944. The “military service club” above did not migrate but was enlarged, presumably for the use of incoming aircraft maintenance personnel and other units. Source: Yōsai Kenchiku Kinmu Dai-roku Chūtai, Kita Hikōjō 56 Hidai Haken Shinobu Han. Jinchū nisshi [Shigenobu Platoon, Sixth Fortress Construction Duty Company, detached (from Iejima) for duty with the 56th Airfield Battalion at North (Yomitan) Airfield. Staff activity report], December 1944. Hong 2020: p. 158.

Hong uses war statistics sparingly. “My concern,” she explains, “is not primarily with the horrendous cost of the war in human lives, utterly shocking as that figure is, but with […] Okinawans who survived the war. In [their] war remembrances, the Battle of Okinawa is never over but is relived daily, in all his horror and confusion” (p. 102). It is the insights of the living about the nature of war and sexual violence that she tries to understand and share her.

Source: Okinawa no Joseishi Kenkyū Gurūpu [Okinawan Women’s History Research Group], ed. In Hōkokushū Henshū Iinkai [Editorial Committee for the Report], ed. Daigokai Zenkoku Joseishi Kenkyūkai no Tsudoi hōkokushū [Report of the Fifth National Colloquium for Research on Women’s History]. Tokyo: Zenkoku Joseishi Kenkyūkai no Tsudoi Jikkō Iinkai [Executive Committee, National Colloquium for Research on Women’s History], 1994, p. 26. The location of airfield sites are from archival documents in the Okinawa War Materials Reading Room at the Cabinet Okinawa Development and Promotion Bureau, Tokyo. Data compiled by Hong Yunshin. Graphic design by Kawamitsu Akira. Hong 2020: p. 105.

There, the general command moved into a vast underground headquarters complex beneath Shuri Castle in February 1945, complete with comfort station. Forced to retreat to the southern tip of the island in late May, army headquarters organized a last stand in the Mabuni hills and caves overlooking the Pacific, going down to defeat in late June.

This article is based on two of my previous reviews of Hong’s book and an essay. The reviews are “Sude ni taningoto de wa nai shintai kankaku” [A Gut Feeling that this is no Longer Someone Else’s Problem], Okinawa Times, April 23, 2016, and “Haijo sareta ryōiki tou itonami: manen suru bōryoku” [Problematizing a Foreclosed Territory: Escalating Violence], Okinawa Times, August 21, 2020. The essay is “Shōgen no ‘ato’: katawara de okite-iru no da ga, sudeni taningoto de wa nai” [What Comes “After” the Testimony? The Events Next Door are no Longer Someone Else’s Worry]. War, Women, and Violence: Remembering the “Comfort Women” Transnationally, International Conference, Critical Studies Institute, Sogang University, March 2019, pp. 63–70.

On August 14, 1991, Kim described her wartime experiences at a press conference in Seoul, using her full name. On December 6 of that year, she joined other Korean victims in a lawsuit against the Japanese state, demanding a clear admission of responsibility for sexual abuse, a formal apology, and legally mandated compensation.

Although comfort women and girls came from a dozen countries and territories in Asia and the Pacific, the public consensus in Japan remains that military sexual enslavement is a bilateral issue between Japan and the Republic of Korea (Tokyo does not officially recognize the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea and thus refuses to acknowledge the existence of North Korean comfort women survivors). In the early 1990s, however, women of several nationalities, emboldened by Kim’s example and assisted by local citizens’ groups, came forward to share their experiences of captivity. More than 90 from the ROK, the Philippines, the Netherlands, Taiwan, and China initiated 10 civil suits against the Japanese government. Several courts, including higher appeals tribunals, admitted plaintiff depositions as evidence, quoting from them in their verdicts, but all cases were ultimately dismissed on legal technicalities raised by the state: the expiration of the statute of limitations, the assertion of state immunity from individual war claims, and bilateral treaty arrangements.

See Hong Yunshin, “Bae Pong-i-san o kioku suru to iu koto: Okinawa no jūmin-shōgen kara no toi” [Remembering Bae Pong-i: Some Questions Raised by Okinawan Testimonies Concerning the Comfort Women]. Presentation to the Working Group on the Elimination of Sexual Discrimination, Human Rights Association for Korean Residents in Japan, Tokyo, April 23, 2021.

Bae died in October of that year, just weeks before Kim joined the first lawsuit to be filed by South Korean survivors in Tokyo.

More precisely, in the 1970s, two books and one film about Okinawan comfort women, including Bae Pong-i, were released, and in Japan proper several important exposés were written about military sexual slavery in general, but none of these works had a lasting impact on the Japanese imagination. In 1976, Uehara Eiko, an Okinawan, published an autobiography under her real name that disclosed her life as an indentured prostitute in Naha’s Tsuji district and later as a military comfort woman. See Tsuji no hana: kuruwa no onatachi [The Blossoms of Tsuji: Women of the Licensed Quarter]. Tokyo: Jiji Tsūshinsha. Yamatani Tetsuo’s 1979 documentary film and book featured Bae’s story, although the book version used a pseudonym. See Okinawa no Halmoni: shōgen/jūgun ianfu [The Halmoni of Okinawa: Testimonies of Military Comfort Women]. Akita City: Mumyōsha, 1979 (86 minutes, 16mm color) and Okinawa no Halmoni: Dainippon baishunshi [The Halmoni of Okinawa: A History of Prostitution in the Japanese Empire]. Tokyo: Banseisha, 1979. Kawata Fumiko’s Akagawara no ie: Chōsen kara kita jūgun ianfu [The House with the Red-tile Roof: The Comfort Women from Korea] (Tokyo: Chikuma Shobō, 1987/2020) would fare better.

The tribunal was organized by women’s groups and featured world-renowned jurists, historians, human rights experts, and 64 surviving ianfu from eight countries: the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, East Timor, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Netherlands, the People’s Republic of China, the Philippines, and the Republic of Korea.

Tomiyama Ichirō & Wesley Ueunten, “Japan’s Militarization and Okinawa’s Bases: Making Peace” (Trans. Wesley Ueunten). Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, 1:2, 2010, p. 356.

See for instance, this reviewer’s Senjō no kioku [Memories of the Battlefield]. Tokyo: Nihon Keizai Hyōronsha, 2006 (revised version), pp. 32–35. The English translation of part of my argument is Tomoyama Ichirō, “On Becoming ‘a Japanese’: The Community of Oblivion and Memories of the Battlefield” (Trans. Noah McCormack), The Asia-Pacific Journal 3:10 (October 12, 2005).

Biopolitics/biopower is that domain in which politics/power has become ascendant, arrogating to itself “the right to kill, to allow to live, or to expose to death.” Achille Mbembe, “Necropolitics.” Public Culture, 15:1, Winter 2003, p. 12.

The restaurant’s red-tile roof caught the attention of U.S. fighter pilots during the air raids of October 10, 1944, and the building was razed shortly after its completion. Hong 2020: p. 170.

See Tomiyama Ichirō, Bōryoku no yokan: Ifa Fuyu ni okeru kiki no mondai [Presentiments of Violence: The Problem of Crisis in Ifa Fuyu’s Writings]. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 2002, pp. 38–42. Some of my main arguments are summarized in English in “The Critical Limits of the National Community: The Ryukyuan Subject” (Trans. John Wisnom & Walter Hatch). Social Science Japan Journal. 1:2, pp. 165–79, 1998. See also Tomiyama Ichirō, Hajimaru no chi: Fanon no rinshō [Beginnings: Fanon, Clinically Situated] (Tokyo: Hōsei Daigaku Shuppanyoku, 2018), pp. 50–55.

Tomiyama Ichirō, “‘Spy’: Mobilization and Identity in Wartime Okinawa,” Senri Ethnological Studies, No. 51, March 27, 2000, pp. 128–29.

Annmaria Shimabuku, Alegal: Biopolitics and the Unintelligibility of Okinawan Life (New York: Fordham University Press, 2019).