Abstract: The Japanese government’s crackdown on the independent Kan’nama Union of concrete mix worker illustrates the fraught position of Japan’s labor movement in decline.

Someone in the Japanese government appears to have ordered a troublesome union to be destroyed. The Kan’nama story has triggered alarming constitutional questions – but little media attention.

For nearly three years, Matsuo Seiko, 49, has kept a toothbrush and a change of clothes stuffed into a bag stored in her hall. The emergency stash can be grabbed in haste if the police arrive and whisk her to a detention center, where she can be interrogated for up to three weeks – without a lawyer in the room.

As an executive in a union that has mysteriously incurred the wrath of Japanese police, Matsuo is bracing herself for arrest. Eighty-one of her colleagues in the All Japan Construction and Transport Solidarity Union, Kansai Regional Ready-Mix Branch (kan’nama), have been detained since 2018, many on what labor scholars call legally dubious charges.

Over 70 union members have been convicted of crimes that include “forcible obstruction of business” (威力業務妨害) for handing out fliers, and “attempted extortion” (強要未遂) for checking workplaces to ensure they are complying with labor laws – both routine union practices in Japan and around the world.

When union member Yoshida Osamu asked his employer for a certificate to prove he had a job (so he could enroll his child in a public nursery school), he was arrested in 2019 for “attempted coercion.” Unusually in a justice system with a 99% conviction rate, he was acquitted last year.

Yukawa Yuji, the head of kan’nama, was arrested on a series of charges and held for 644 days while a parade of detectives interrogated him. Yukawa was blocked throughout his detention from seeing his wife and two children and had limited access to a lawyer. He is now on remand on charges of forcible obstruction of business and attempted extortion.

Yukawa Yuji, the head of Kan’nama

Yakuza thugs were allegedly used to harass union members. In addition, multiple members have reported intimidation and coercion by police during custody. Some have been told the investigation would stop if they quit kan’nama. “A detective kept saying to me, ‘you’ve got no future if you stay in this union’,” recalls Yukawa. Employers have been told to shun unionized workers. These tactics appear to work: over 800 members of kan’nama, 1,300 at its peak, have quit since 2018.

Yukawa says the length of detentions, the cooked-up legal charges and the statements by interrogators are evidence that someone powerful has ordered the Osaka-based union to be taken down. “The police, the prosecutors and the government are trying to crush us, but we will not be beaten,” he says.

None of the relevant police forces will comment on these claims. Tano Takeshi of the Osaka Prefectural Police security department, said it would not discuss the investigation of specific cases. Shiga Police did not return calls requesting comment. The handful of journalists who have looked into the arrests have met similar stonewalling.

The extraordinary police time expended on targeting Yukawa and his colleagues has attracted little attention in the mainstream Japanese media. A new book “Chingin Hakai (Wage destruction)” by Takenobu Mieko, a former journalist with The Asahi Shimbun, Japan’s flagship liberal newspaper, says most senior editors are aware of the story but have shunned it.

“It’s considered a difficult story to report,” she says. Journalists who take the authorities’ claims against the union at face value will be criticized by liberals, but rejecting that view means going up against the police and powerful prosecutors – and losing access. The net result is self-censorship, she says. “Editors have said ‘sawaranukami ni tatarinashi’, (let sleeping dogs lie).”

Scholars and lawyers have been more forthright. Dozens, including labor law experts from Waseda, Chuo, Ritsumeikan, Hokkaido, Nagoya and Osaka City universities have signed a petition calling the assault on Kan’nama the largest criminal case involving a labor union since the Second World War. Deeming “routine union activities illegal and criminally punishable” renders Article 28 of Japan’s Constitution (guaranteeing workers the right to organize collective action) “meaningless,” the statement said. The academics called the repression of the union “unprecedented.”

Uncompromising

Formed in 1965, kan’nama has a formidable reputation for defending its members’ interests. Unlike most Japanese labor unions, which are company-based (and therefore structurally invested in the interests of their employers), it represents workers across multiple firms in the industry and negotiates pay and conditions aggressively.

Over the years, it has clashed, sometimes violently, with employers. The union’s official history records that two of its officials have been killed by gangsters hired by construction companies (yakuza involvement plagues the small companies that haul cement in the Kansai region). It notes previous official campaigns against the truck drivers, in around 1980 and 2005 – though the latest is the worst.

An award-winning 2008 documentary film “フツーの仕事がしたい (A Normal Life, Please)” depicts attempts by a truck driver, Kaikura Nobukazu, to join the union, after being ground down by a deeply exploitive working system (The movie says Kaikura drove his cement truck for 552 hours in a single month). At one point he is threatened and assaulted by yakuza thugs who demand he quit the union.

As Japanese trade unionism has grown more pliant, kan’nama has stuck to its militant guns: one of its regular activities is driving its trucks outside the homes of construction bosses and protesting loudly. Its rallies are reliably lively and noisy, with taiko drummers, peace slogans and bursts of “The Internationale.”

In December 2017, the union went on strike. Organized by the Osaka branch of the All Japan Dockworkers Union, the key demand was a rise in pay for drivers transporting cement and ready-mixed concrete around the city’s building sites. About 1,500 transport runs to sites around the Kinki region (centered on Kyoto, Osaka, Hyogo, Wakayama and Shiga prefectures) were halted.

The strike infuriated construction bosses and politicians around the Kansai region and surely hardened official sentiment against the union. Many see kan’nama as an anachronism, and its emphasis on collective bargaining among small contractors a nuisance because it increases their negotiating power against the big companies.

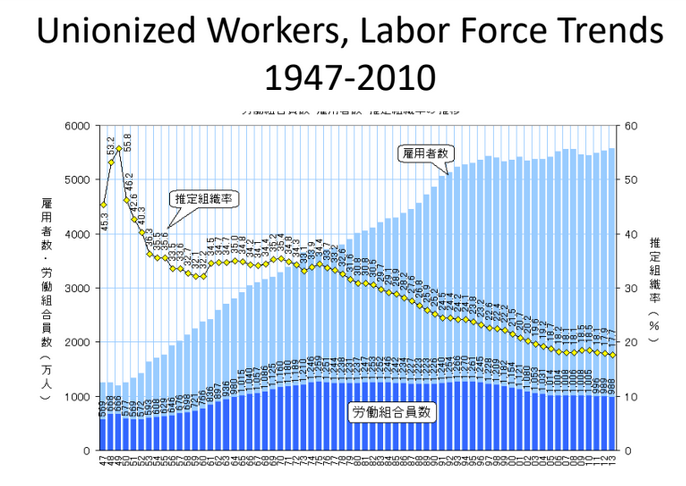

Kan’nama’s practice of old-school union tactics came against a background of mass workforce casualization and stagnant or declining pay in Japan. The percentage of non-regular Japanese employees grew by about 8% from 2002 to 37.3% by 2017. In a country where workplace disputes were once common (around 9 million workdays were lost to disputes in 1974-75), strikes have dwindled to negligible levels.

With Japan’s population falling, almost everybody who wants a job has one: unemployment fell to just 2.7% in February 2022. Demographic decline has collided with rising labour demand. This combination should be highly inflationary because scarce workers should be demanding higher wages. But pay and prices remain subdued. One reason is that in their negotiations with employers, Japan’s labour unions have rarely been aggressively confrontational.

Perhaps not coincidentally, workers’ compensation has shrunk sharply and corporate profits have risen exponentially. A recent paper in Toyo Keizai notes that during 1995-2017, productivity (GDP per work-hour) in Japan grew by 30% but hourly worker earnings fell 1%. “This performance is particularly shocking considering that, until recently, Japan’s workers got a higher share of national income than workers elsewhere,” notes author Richard Katz.

All this made Kan’nama the proverbial nail that stuck up, says Watanabe Makoto, a former Asahi journalist who now runs the online investigative news site Tansa. The hammer was Japan’s National Police Agency (NPA), which he says would have been unlikely to leap into action without direction from above. “There is no FBI in Japan so to operate across prefectural borders (Shiga, Osaka, Kyoto, and Wakayama) the NPA had to be involved,” says Watanabe.

But who ordered the hammer to fall? Speculation has fallen on someone within the government, says Watanabe, who notes that among the listed groups in parliament is the ‘wet concrete Diet members caucus (生コン議員連盟),’ which would surely have taken an interest in the 2017 strike. The head of the caucus is former president and CEO of Aso Cement, Aso Taro, also the vice-president of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party.

It is not necessary to believe in conspiracy theories – that the police, prosecutors and big contractors conspired to stitch up a troublesome union – to conclude that there was an organized crackdown, says Nakai Masahito, an Osaka-based lawyer who represents Kan’nama. “There is no way that the police across all these prefectures acted alone. It is unthinkable. They had to have been directed in some way,” he concludes.

Many observers accept that the union has a fearsome reputation but say it has always stayed on the right side of the legal line. “They’re considered radical and the media considers them difficult to cover but they’re not radical at all, they’re just trade unionists,” says Koyano Takeshi, general secretary of the All-Japan Construction and Transport Union (Rentai). “They haven’t broken any laws.”

Why haven’t newspapers taken more interest? Watanabe speculates that one reason is the elitism of the media industry. “Journalists go to the best universities and they don’t understand trade unionism,” he says. “And newspaper unions are also company-based. If one newspaper is being bashed, the other newspapers don’t help out. Lack of solidarity is a feature of the unions here.”

Matsuo was a single mother with three children when she began driving a concrete truck over 20 years ago. One of her twins was in and out of hospital a lot. “I couldn’t raise three children on a regular office job,” she recalls. “Just saying you had three children on the phone was a no-no. There are a lot of night jobs for single women, but I’m not cut out for that. And I’ve loved big cars and trucks since I was little.”

The dispute has since split her family apart. Of four members of the union – Matsuo, her husband, her brother-in-law and her father-in-law – she is the only one left. Her husband and brother were arrested and quit soon after. Her father retired. She lost her job. “Even though nobody had done anything wrong, everyone was being arrested,” she says. “Everyone began only thinking about themselves. I understand that they have a life to live. But I’m really angry at the people who left.”

One Member’s Story

Tanaka Junko has been driving a concrete truck for 25 years. As a single mother of a young son, she once drove car transporters for a living through the night. In the winter, she learned how to wrap snow chains around the wheels by the side of the road. “It was a job an ordinary woman could do and it was very well paid – 350,000 yen – 400,000 yen a month,” she recalls. But there was a catch. Drivers were encouraged to stay off the main motorways to save money on highway charges, which lengthened their journeys. “I’d drive like crazy, starting at about 10:00 p.m. the night before – and would finish at 3:00am or 4:00am,” says Tanaka. “That would save 50,000 to 60,000 yen in highway fees. I was starting to doze off at the wheel and realized I could actually lose my life. I was driving all night and taking care of the house during the day. I wrecked my body and I was worried about my child. Someone suggested driving concrete-mixers. That’s how it all started.”

Tanaka first encountered the kan’nama union when she was riding a mixer truck for a concrete firm. She protested against a pay cut during Japan’s end of year (shogatsu) and summer (o-Bon) holidays by joining the union. She has a keen awareness of the difference between industrial unions and company unions. “In company unions, you join with everyone else and there is no sense of being in a labor union at all. Industrial unions are voluntary. You learn about trade unionism and are very conscious of the fact that you are a member. I learned a lot of things. ‘Oh, I have rights, the right to negotiate as equals with employers, the right to exercise and strike in a union’. They didn’t teach me that in school. It wasn’t so much about strength as unity – we could negotiate as equals. I realized for the first time at the age of 30.

Tanaka’s husband is in the concrete business too, but for a rival company. They had fierce fights when the strike began. “He asked: ‘what will you do if you can’t afford to eat.’ But we’re doing nothing wrong. At one point, with friends being arrested and everything in a state of confusion, I almost fell apart a few times. But I knew I couldn’t back down. I want to do my best in the movement and in the disputes without losing heart, and I don’t want to lose. I don’t care if we win, but I don’t want to lose.”