Abstract: Onodera Makoto (1897–1987) served as the Japanese military attaché in Stockholm 1941–45. His accomplishments during WWII made him instantly famous when they became known to the public in 1985 with a documentary about him on NHK based on a memoir by his wife, Yuriko. One of his famous deeds took place in mid-February 1945 when he allegedly sent a telegram to the Japanese General Staff shortly after the Yalta Conference in February 1945 warning that Stalin during the conference had promised that the USSR would attack Japan three months after the German surrender. After the German capitulation on 7 May, the Soviet Union joined the war against Japan on 9 August, precisely as Onodera had predicted. The problem is that no one has been able to trace this telegram. However, wartime documents, most of them traced in Swedish archives, show that the famous story of ‘the lost Yalta telegram’ is invented.

Keywords: World War II, intelligence, Yalta Conference, Onodera Makoto, Karl-Heinz Krämer

Introduction

Colonel Onodera Makoto (1897–1987) of the Imperial Japanese Army arrived in Stockholm in January 1941. He took up his post as the Japanese military attaché in early February and served throughout the war. What is known about his activities is in large part based on memoirs, recollections and interviews made decades after the war. The large-scale destruction of documents before and after the final stage of the war has resulted in that hardly any documents related to his activities in Stockholm are found in Japanese archives. Even though Onodera’s fame is based on his activities in Stockholm, no researcher or journalist has searched for documents in Sweden. An attempt to fill this glaring lacuna is my new study Master Spy on a Mission: The Untold Story of Onodera Makoto and Swedish intelligence 1941–1945 (London: Amazon, 2021). I have accessed wartime documents from Swedish archives along with documents in The National Archives (TNA) in London to reassess the consensus view in Japan and Sweden about Onodera’s work in Sweden as an intelligence officer.

During his years in Stockholm, Onodera continued his hard-working habits honed from his previous stint as the military attaché in the Baltic countries, 1936–38. Networking and cooperation were vital for obtaining information. He provided Tokyo with a steady stream of intelligence reports based on his extensive collaboration with Axis intelligence officers and networks under two of his acquaintances from his previous assignment in the Baltics, the former Estonian intelligence chief Colonel Richard Maasing and the Polish intelligence officer Major Michał Rybikowski, both refugees in Sweden. Onodera collaborated also with intelligence officers working for the enemy, because he believed he could separate the wheat from the chaff. One was Rybikowski. Even though Onodera was aware that the Pole worked for the British, he became so close a partner that Onodera described him as his chief of staff. It was a mistake. The Pole was double-dealing for years as the key operator of a successful British high-level deception operation targeting Onodera. In August 1943, this operation was jeopardized when the Pole was caught red-handed involved in spying. He had diplomatic immunity and was discreetly asked to leave Sweden. He saved the operation by talking Onodera into believing that the Pole would continue to provide intelligence from London. Thus, even though Rybikowski no longer worked at Onodera’s office or participated in the operation, British-produced bogus information continued to be handed over to Onodera until June 1945.

What about Onodera and his host country? Sweden had been able to keep out of World War I by stubbornly clinging to its policy of neutrality. In the aftermath of the war, Sweden adopted a pacifist disarmament policy in 1925. However, developments on the European continent in the 1930s increased the political and military pressure on Sweden. A new defence policy was introduced in 1936. Overall, the defence budget increased from 1.5 per cent of GNP in 1936 to six per cent in 1939 and twelve per cent in 1940. The security apparatus was beefed up. Three organs were involved in counterintelligence. The Intelligence Department (renamed the Home Section in 1942) of the Defence Staff was entrusted with internal intelligence. The C-Bureau of the Defence Staff was established in 1939 as a secret intelligence service. The Sixth Division of the Stockholm police (often called ‘the secret police’) was responsible for domestic security (surveillance, telephone and postal control, etc.) across the country. The role of the signals-intelligence unit of Defence Staff became so central that it became an independent agency in 1942.

In Tokyo, Sweden was seen as being within the German sphere of influence. Since Onodera viewed it likewise, he underestimated his host country. The three counterintelligence organs had been alerted by the foreign ministry of Onodera’s arrival and kept him under surveillance. Moreover, the organization he inherited from his predecessor was penetrated already when he arrived.

The German military traffic intercepted by Swedish signals intelligence indicated in 1942 that Onodera shared intelligence with the Germans on a considerable scale. An opportunity to get access to his information, find out his sources and keep a check on him opened when the C-Bureau learned that Richard Maasing worked for Onodera; Maasing had furnished information to Swedish military attachés when he was the head of the Estonian intelligence service in the 1930s. A top official of the C-Bureau, Captain Gunnar Grip, contacted Maasing in December 1942 and they agreed to swap information. This exchange began in January 1943. The next month Maasing introduced Grip to Onodera. Onodera must have been pleased when Grip not only began to pay visits quite frequently but also to hand over the information directly to Onodera. Too eager to secure access to the information, Onodera attempted to recruit Grip but this resulted in the Swede severing contact with Onodera. However, Grip continued until December 1944 handing over information to Maasing, who forwarded it to Onodera. The real purpose of the forthcoming stance towards Onodera taken by the Swedes is hidden behind what a US intelligence report revealed in 1945; the information Grip and Maasing had given Onodera was largely inaccurate.

I devote two chapters of my book to the mystery surrounding Onodera’s two most famous deeds related to actions in spring 1945 that are attributed to him. One story is about a telegram that he said he had sent to the Army General Staff in Tokyo shortly after the Yalta Conference in February 1945 warning of Stalin’s commitment at the conference pledging to attack Japan three months after the German surrender. A modified version of my chapter about Onodera’s famous telegram is found below.

In Japan, the debate about whether or not Onodera sent his famous telegram has been going on ever since he brought it up. A consensus seems to have evolved asserting that he did send the telegram. Still, no one has been able to locate it in any archive. It is not clear that Tokyo would have altered its policy towards the Soviet Union and the endgame of the Pacific War even if the specific warning was telegrammed because it might not have reached the right people, might not have convinced them, could have been dismissed as disinformation or was at odds with the prevailing consensus. However, combined with Moscow informing Tokyo in April 1945 that it would not renew the non-aggression pact one year before it was due to expire, the warning might have set off alarm bells among Japanese military officials and diplomats. Yet in June 1945, Japan was still banking on the Soviet Union to broker a peace deal with the United States and instructing its ambassador in Moscow Satō Naotake to arrange for this. Ambassador Satō was skeptical and queried Tokyo, but his instructions remained unchanged, suggesting that there were still hopes in Japan that the Soviet Union would help soften the terms of unconditional surrender that Washington insisted on.

Contemporary documents from the war years in Swedish archives reveal that Onodera did not send this now-famous ‘lost’ telegram. Moreover, I prove that the same can be said about his second famous deed in spring 1945. That is the story of ‘the Onodera peace feeler’ in May 1945, purportedly involving the Swedish king, Gustaf V, that evaporates when contemporary documents from the war years are taken into account.

The Lost Telegram That Was Not

‘Russia will probably not enter the war against Japan,

neither has the Soviet Union any interest

in running errands for the Allies.’

Onodera, as quoted in a Swedish agent report to the Home Section, 31 May 1945.

‘The Lost Yalta Telegram’

In February 1945, Josef Stalin, Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Churchill met at Yalta, a resort town on the Crimean Peninsula. They discussed several towering issues related to the war, how to continue the war effort against their enemies, and the post-war order. One of the topics discussed was the war effort against Japan. An agreement was reached and signed by the supreme leaders of the Allied powers on 11 February 1945. It detailed how to pursue the war against Japan which in the not too distant future would be the sole remaining enemy after the German surrender.1 The leaders agreed ‘that in two or three months after Germany has surrendered and the war in Europe has terminated the Soviet Union shall enter into the war against Japan on the side of the Allies […].’2 While Stalin had made similar promises at previous conferences, his commitment at Yalta was put on paper. This agreement was a closely guarded secret until it was made public simultaneously in London, Moscow and Washington on 11 February 1946.3

Onodera maintained that he had received information from London about the Soviet promise to enter the war against Japan not long after the conference and realizing its tremendous importance, he immediately informed the Army General Staff in Tokyo. Japan had signed a five-year non-aggression treaty with the Soviet Union in 1941 and did not worry unduly about a Soviet attack. Onodera’s information about the Soviet Union’s intentions should have caused Japan to reconsider its whole national strategy. But nothing happened. Instead, when the Japanese government tried to find a way to end the war, it pinned its hopes on Moscow.

Onodera claimed also that it was not until decades later, in 1983, that he realized his information had not reached the top echelons of the Army General Staff.4 His statement that he had cabled Tokyo about the Yalta agreement, but the telegram had gotten lost, has entered the annals as ‘the lost Yalta telegram’. This telegram is equally famous for its contents as for its purported status of having been lost. In the aftermath of Onodera’s revelation, a heated debate has occasionally flared up about why and how this allegedly crucial telegram disappeared.5 Many have found it hard to accept the facile argument that the telegram had somehow not reached its addressee or that it had by some means been spirited away. This hotly debated issue can be settled by bringing in contemporary documents from the war years traced in Swedish archives.

British intelligence intercepted Onodera’s wartime intelligence traffic. The intelligence researcher Kotani Ken has searched for Onodera’s Yalta telegram in TNA where decrypts of a large number of Onodera’s wartime reports are archived. Kotani’s searches yielded nothing. He wrote later that ‘strangely enough’, Onodera’s report on Yalta is missing from the TNA file where it should be archived (Kotani 2020, 156). Another attempt to trace Onodera’s telegram in TNA is reported in Okabe Noboru’s Kieta Yaruta mitsuyaku kinkyūden [The lost emergency telegram about the secret Yalta agreement] (2012). While Okabe was as unsuccessful as Kotani in his effort to trace the telegram in TNA, he nonetheless claims that Onodera did send this telegram. One piece of circumstantial evidence traced by Okabe is a circular sent to all German embassies and legations by the Auswärtiges Amt [German foreign ministry] on 14 February 1945. He translates this circular into Japanese as reporting, inter alia, that

a report from a reliable and important source received on the ninth from the German legation in Stockholm … at the Yalta Conference, the Soviet Union has changed its policy towards Japan, that is, it decided to join the war […]. According to diplomatic sources, from the first day of the Yalta Conference, it has been hinted that Stalin has agreed to join the war against Japan. (Okabe 2012, 48)

The translation of the circular as presented by Okabe is misleading. The decrypt of this circular is found in TNA and differs crucially from the Japanese translation provided by Okabe. The translated decrypt reads, inter alia:

Our Stockholm Legation reported on the 9th instant:

A reliable agent [Vertrauensmann] reports: – A final Lend-Lease Agreement has now been concluded between representatives of the United States, Great Britain, Canada and Soviet Russia according to which the Soviet Union has declared itself to be ready in principle to alter its policy towards Japan. […] According to information from diplomatic channels, not only in Washington but in London also, Stalin indicated his assent to the change in Russia’s Japanese policy on the first day of the Three Power Conference which is now taking place. […] London reckons first with [group missed: ? rupture of] commercial relations and finally diplomatic relations between the Soviet and Japan.6

Contrary to Okabe’s claims, nothing in the above circular states unequivocally that the Soviet Union had agreed to join the war. Instead, the circular modestly states that the Soviet Union has declared itself to be ready to change its policy towards Japan. No mention is made of the nature or form of this change. The British decoders have added their best guess that the shift implied an impending break (‘rupture’) of first commercial and then diplomatic relations between the Soviet Union and Japan.

Okabe has located another document that he argues supports his claim that Onodera sent the famous telegram. Japan’s ambassador to Germany during World War II, Ōshima Hiroshi, testified in 1959—fourteen years after the war—that he had reported to the foreign ministry sometime in March 1945: ‘The outcome of the Yalta Conference is that Russia (the Soviet Union) will join the war against Japan at an appropriate time’. Ōshima based his report on information from the German foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop. Okabe believes that Ribbentrop relied on the Stockholm information that was disseminated by the aforementioned Auswärtiges Amt circular on 14 February 1945 (Okabe 2012, 54).

A New Primary Source

While considerable efforts have been made by Kotani Ken and Okabe Noboru to search for contemporary documents that could throw light on the ‘lost’ Yalta telegram, there is one option hitherto unexplored by researchers—going over the material generated by the extensive intelligence exchange between Onodera and Karl-Heinz Krämer at the German air attaché’s office in Stockholm. Krämer, who was seen as the German intelligence ace in Stockholm, collaborated extensively with Onodera from late summer 1944. Krämer’s reports sent to Berlin by teleprinter from January to mid-April 1945 were surreptitiously copied by a mole working at this office, who handed them over to the Swedish, British and Czech intelligence services (McKay 1993, 126). These copies are found in the archive of the Swedish Military Intelligence and Security Service (MUST). Given that it was vital for both Onodera and Krämer to obtain information about the Yalta Conference, it is reasonable to surmise that any information secured would show up in their intelligence output. Their close cooperation also made it reasonable to assume that Krämer’s telegrams about the Yalta Conference would have contained information collected by Onodera. These conjectures turned out to be correct. No less than twenty of Krämer’s approximately 450 telegrams in the MUST archive touch on the Yalta Conference, and in some cases, the source for these was identified as No. 26, that is, Onodera. Drawing on the wartime documents in Swedish archives related to the Yalta Conference including Krämer’s reports provides a basis for reassessing the ‘lost’ telegram.

Contacts between Onodera and Krämer around the Time of the Yalta Conference

Krämer and Onodera were involved in an exchange that was in full swing from late summer 1944. When Superintendent Otto Danielsson of the Sixth Division cross-examined Krämer in March 1946, the German claimed that Onodera had orally conveyed 60–80 ‘messages’ to him. In a comment, Danielsson states that he was firmly convinced the number of meetings between Krämer and Onodera was equal to the number of messages because they constituted Lageberichte or ‘situation reports’.7 Onodera was interrogated at Sugamo Prison in 1946 and told his interrogators that he had met Krämer ‘once a week either in the German Embassy or in the office of Onodera, and from time to time in the apartment of one of the latter’s assistants.’8

What then is known about their contacts leading up to and during the Yalta Conference? The answer is—quite a bit. In February 1943, the Sixth Division became aware that Krämer was involved in espionage and began to monitor his activities. From 8 December 1944 until the end of his stay in Sweden, he was put under surveillance day and night, with only one exception. He left Sweden on 14 December 1944, but his return is not recorded.9 However, Onodera mentions in a telegram to Tokyo that Krämer was back the next day.10 This remark implies that Krämer was under constant surveillance while the conference was on the agenda. As for Onodera, he was watched for most of 1945.11 However, Onodera’s surveillance reports before 4 July 1945 have not survived. The lack of records is likely due to a decision in 1948 to destroy all such records if they were deemed to be unneeded in the future (Flyghed 1992, 307f).

The Krämer surveillance records indicate that he and Onodera met more frequently than usual around the time of the Yalta Conference. Incidentally, a US intelligence report from 15 February 1945 specified that Onodera ‘is a frequent visitor of the counter-espionage office of the German Intelligence’.12 Krämer was always shadowed. Police officers followed him when he visited Onodera’s office at Linnégatan 38 shortly after 4 pm on 8 February. On 13 February, they lost him for a while but saw him again on Linnégatan at 11.10 pm after probably having met with Onodera. Another meeting took place on 21 February. Those tasked with following Krämer noted that he and his assistant Heinrich Wenzlau left their car close to Linnégatan 38 shortly after 4 pm. When they returned to their car, Krämer carried a large brown envelope, which his shadowers confirmed he brought to the German legation.13

The Yalta Conference in Krämer’s Telegrams

The sheer number of Krämer’s telegrams on the Yalta Conference is an indication that the conference was of considerable interest to him and his superiors. Some telegrams are short; others are fairly long. The majority of the longer ones unsurprisingly date from February 1945. One telegram on 13 January stated that the United States needed the Soviet Union’s help in dealing with Japan and that the Soviets were not anxious to assist. It was further reported that the most drastic step would be for the Soviet Union to sever its diplomatic relations with Japan.14 Krämer sent a telegram to Berlin two days later reporting that Washington opposed General Charles de Gaulle attending the conference but the Soviet Union was in favour of his attendance. This revelation should not be a surprise as de Gaulle’s fear that France would become subjugated to the US-UK allies had resulted in discordant relations between France and the Anglo-Saxon countries. He had also just signed the French-Soviet treaty of alliance and mutual assistance (Gueldry 2001, 48ff). Krämer added that worsening Soviet-Japanese relations would be one of the topics at the meeting.15 On 17 January, Krämer sent another telegram based on source 26, namely Onodera, reporting on war fatigue in the southern United States, anti-war demonstrations in the western US states, and the fact that the Soviet embassy was spreading rumours of a Soviet declaration of war against Japan when the war in Europe was over.16

Krämer outlined the general situation surrounding the Yalta Conference in a telegram sent on 2 February, two days before the conference started, reporting it was true that rumours were spreading in London about possible US air forces in Siberia:

Behind this lies the American plan to, using all means available, come up with clarification with the SU about relations in East Asia. According to information from the Foreign Office, the US is inclined to make far-reaching concessions to the Russians, if the SU either participates effectively in the war against Japan, or at least provides air bases against Japan of considerable scope, ceases all trade, also transit, with Japan, and breaks diplomatic relations.17

On the fifth day of the conference, 8 February, the same day on which police surveillance in Stockholm observed Krämer visiting Onodera’s office, he sent a report that he claimed was based on information from Z.V.-Mann (most likely Onodera). This is the report that the Auswärtiges Amt received on 9 February and referenced in its 14 February 1945 telegram quoted by Okabe. The visit took place at 4 pm, which gave Krämer ample time later that day to furnish Berlin with the information provided by Onodera. The differing dates indicate that Krämer had sent the telegram so late on 8 February that the recipient in Berlin only attended to it the following day. The telegram reads, inter alia:

Between USA–UK–Canada and SU a Lend-Lease agreement has now finally been reached after the SU has declared itself prepared to fundamentally change its Japan policy [nachdem SU grundsätzlich zu Änderung seiner Japanpolitik bereit erklärt hat].

It had however not yet been decided

in which form the SU will participate in the war against Japan. According to diplomatic information in Washington as well as in London, Stalin has however during the first days of this presently ongoing conference already conceded to a fundamental change [grundsätzliche Änderung] of the SU-Japan policy. Supreme Commander of the American air force, General Arnold, has brought to the discussions a detailed plan for the establishment of airbases for the US air force in eastern Siberia. London counts first on a break of trade relations and finally also the diplomatic relations between SU and Japan.18

As can be noted, the circular sent by the Auswärtiges Amt on 14 February tallies closely with Krämer’s report. The critical point is that the Soviet Union had declared it was prepared to change its Japan policy fundamentally. Nothing was said about exactly what this change implied. Uncertainty reigned as to how and when the Soviet decision to change its policy would be implemented. Nothing was said about the Soviet Union entering the war, only that London (the British Foreign Office) predicted a break in Soviet-Japanese trade relations followed by a termination of diplomatic relations.

Four days later, Krämer sent another report allegedly based on information from the same source, Z.V.-Mann. It is titled ‘On the three-power conference’ and emphasizes the significantly different views held by the participants. It reads:

[…] According to information within the [British] Foreign Office, the question of the post-war and peace organization has not yet been discussed at the conference of the three. London also does not believe that final decisions will be reached since the SU and USA proposals are too far from each other. Since the whole complex of questions brings with them questions of principle for both countries, the solution will be left to later conferences.19

In an archived report lacking a date but known to have been sent sometime between 16 and 18 February, Krämer noted that Anglo-American air force cooperation with the Soviets had sped up following the decisions taken at the Yalta Conference.20

On 21 February, the day when the police surveillance observed Krämer visiting Onodera at 4 pm and returning to the German legation with a large envelope, he filed a lengthy report on the conference to Berlin. Two passages in the copy of the archived telegram are rendered as ‘—’ because of damage to the photograph underlying the typed text. The missing parts are added within brackets.

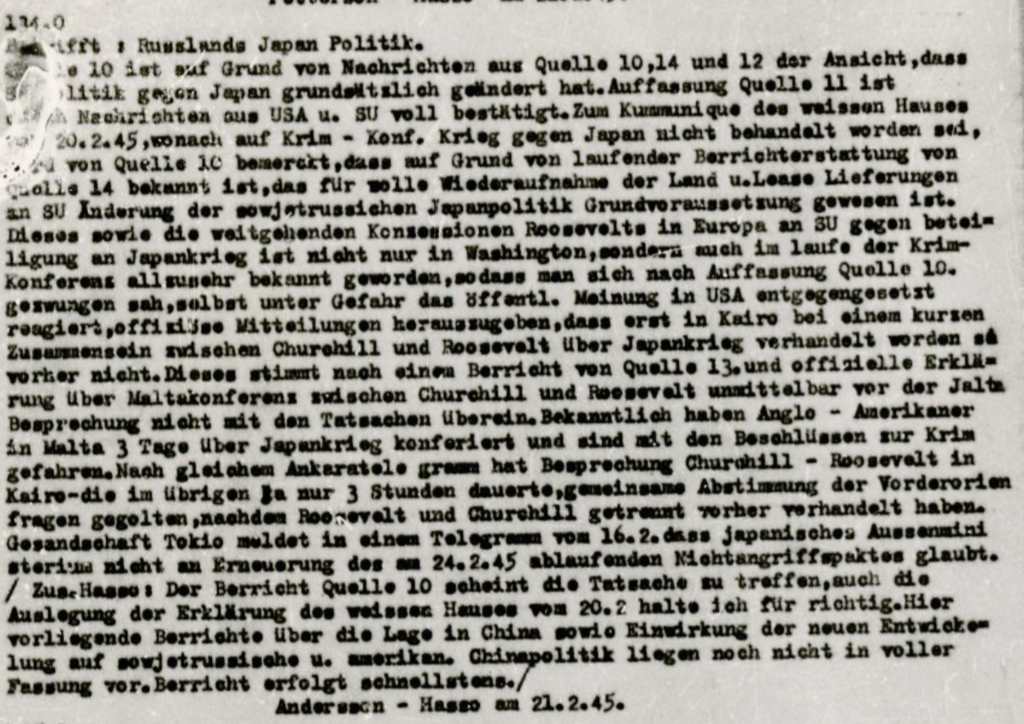

Re: Russia’s Japan policy

Source 10 based on news from sources 10 [sic!], 14, and 12 is of the view that — [SU] policy towards Japan has changed fundamentally. The view of source 11 is — [through] news from the USA and SU wholly confirmed. Regarding the communiqué on 20.2.45 from the White House that the war against Japan has not been discussed at the Crimea Conference, the view of source 10 is to remark that based on current reporting of source 14 it is known that a change of the Soviet Russian Japan policy has been a fundamental precondition for a full restart of Lend-Lease deliveries to the SU. This, as well as Roosevelt’s far-reaching concessions in Europe to the SU in order to obtain its participation in the Japan war, has become all too known not only in Washington but also during the Crimea Conference, so that according to source 10, one saw itself forced, even risking that the public opinion in the USA might react against it, to publish officious messages that negotiations over the Japan war had taken place only at a short meeting in Cairo between Churchill and Roosevelt [and] not before. This is not in agreement with a report of source 13 and the official declaration on the Malta Conference between Churchill and Roosevelt immediately before the Yalta discussions. It is known that the Anglo-Americans discussed the Japan war for three days in Malta and have gone to Crimea with their decisions. […] Embassy in Tokyo reports in a telegram of 16.2 that the Japanese foreign ministry does not believe in a renewal of the [Soviet-Japanese] non-aggression pact that ceases 24.2.45. / Added by Hasso [Krämer]: View of source 10 seems to render facts correctly, and I consider correct also the explication of the White House declaration on 20.2. […].21

Photocopy of Krämer’s telegram on the Yalta Conference, 21 February 1945. This is one of several hundred photographed telegrams that Expressen received in early 1946. Along with other similar telegrams, it formed the basis of its scoop on clandestine German activities in Sweden during the war. As seen here, the photograph underlying the typed text is damaged. (Photo: Bert Edström)

Krämer’s telegram confirmed the report he had sent on 8 February about the change of the Soviet Union’s Japan policy. However, there is a crucial difference compared to his previous report. He could now present a trustworthy evaluation of what had taken place at the conference. Source 10, representing official Swedish views, supported by sub-sources 11–14, reports from the Swedish legations in Madrid, Moscow, Paris and London, was of the view that the Japan policy of the Soviet Union had fundamentally changed. This conclusion was based on the Swedish view that such a change was a fundamental prerequisite for resuming the Lend-Lease deliveries to the Soviet Union as had been decided at the conference. Following the information he received from Swedish sources, Krämer discarded the claim by the White House that the war against Japan had not been discussed at the conference. He also reported that President Franklin D. Roosevelt was said to have made far-reaching concessions in Europe to the Soviet Union to bring it into the war against Japan. Krämer added that according to the German embassy in Tokyo, the Japanese foreign ministry did not believe that there would be a renewal of the non-aggression treaty.

Krämer’s report presents a reliable analysis concluding that a change of Soviet policy towards Japan had taken place. Exactly what it meant in practice was, however, uncertain. It was not known, in particular, whether the change meant that the Soviet-Japanese non-aggression treaty would not be renewed or that the Soviets had promised to join the war against Japan militarily.

On 23 February, two days after Swedish police officers observed Krämer carrying a large envelope from Onodera’s office to the German legation, he filed no less than five reports to Berlin. The first two were based on information provided by Onodera, who was forwarding information supplied by Haifisch, the Army General Staff in Tokyo. The first report was about US forces in the Philippines.22 The second concerned Soviet-Japanese relations:

According to information from Haifisch, the report of the embassy in Moscow about the Crimea Conference [gives] no significantly different impression than messages from Berlin also given by us, information about the change of SU policy. The foreign ministry is also of the view that SU has in principle changed its policy towards Japan, as a result of which [it] is still open in which way SU will act.23

Thus, the Japanese foreign ministry was of the view that the Soviet Union had in principle changed its Japan policy. This was probably based on a report to the ministry by Japan’s ambassador to Berlin, Ōshima Hiroshi, on 15 February. At the conference, ‘Stalin agreed to change his policy towards Japan and in particular granted the use of air bases in the Far East.’24 However, Ōshima said nothing was said about a Soviet military attack against Japan. This telegram ended essentially Krämer’s reports about the Yalta Conference. Henceforth, the conference figures only occasionally as a peripheral matter in his telegrams to Berlin.

The Kotani-Yoshimi Findings

Yoshimi Masato discusses the ‘lost’ Yalta telegram in Shūsenshi [A history of the end of the war] (2012). His examination is based on the decrypts of Onodera’s telegrams traced in TNA by the intelligence researcher Kotani Ken. While Kotani was unable to locate the telegram, Yoshimi takes into account two other telegrams discovered by Kotani in TNA. Onodera sent the first to the Army General Staff in Tokyo on 19 February:

Please send me information on the following points:

1. Changes in the dispositions of Red Army (and Red Air Force) in Eastern (and Central) Europe.

2. Russian strategic reserves.

3. Intelligence material on the three power conversations.25

The second telegram is a response from the Army General Staff dated 21 February. The response to the third point raised by Onodera is:

With reference to the Three-Power Conference, there is little change to report apart from information which is available at your post, but we are carefully watching the frequent tendency of enemy comment to suggest that Russian policy towards Japan is taking a more positive line, and you are asked to report in particularly full detail in this connection.26

The key phrase in the Staff’s telegram is ‘there is little change to report apart from information which is available at your post’. This passage implies that the Staff’s knowledge was based on information ‘available at your [Onodera’s] post’, that is, the information provided by Onodera. This strongly suggests that he had submitted a previous report about the conference. His telegram of 19 February was thus a query on what others had reported.

Based on this exchange between Onodera and the Army General Staff, Yoshimi argues that Onodera must have sent the famous Yalta telegram that somehow got lost (Yoshimi 2012, 83). However, this conclusion is speculative and unsupported by available archival evidence. From 1983 onwards, Onodera claimed that the telegram he had sent shortly after the Yalta conference contained the very specific information that the Soviet Union had agreed to attack Japan three months after the German surrender. It would be strange indeed if such upsetting information would not have merited a specific comment from the Staff. Instead, they just responded that ‘we are carefully watching the frequent tendency of enemy comment to suggest that Russian policy towards Japan is taking a more positive line’. This statement is hard to reconcile with a message that Moscow had promised to join the war against Japan.

As Yoshimi points out, the telegram indicated that the Army General Staff was dissatisfied with the lack of detail in Onodera’s report and therefore asked him ‘to report in particularly full detail’. More importantly, the existence of this telegram refutes Onodera’s claim that he had not received any response from the Staff about the Yalta telegram (Yoshimi 2012, 83). That the reaction in Tokyo was one of dissatisfaction is easy to understand: the report was uncertain and therefore of limited value to the Staff. It is clear that Onodera had informed them of the change in the Soviet Union’s Japan policy without clarifying the nature or form of this change. The lack of precise information contradicts the contention that he had sent a message with information as unambiguous as ‘the Soviet Union is going to join the war against Japan three months after the German surrender’.

One passage of Krämer’s report sent to Berlin on 23 February resembles the telegram from the Army General Staff to Onodera on 21 February 1945. Compare ‘there is little change to report apart from information which is available at your post’ (Tokyo 21 February) and ‘the report of the embassy in Moscow about the Crimea Conference [gives] no significantly different impression than messages from Berlin also given by us, information about the change of SU policy’ (Krämer 23 February). This is a strong indication that Onodera had informed Krämer of the telegram from Tokyo when they met on 21 February. With the eight-hour time difference between Tokyo and Stockholm, Onodera would have had plenty of time to study the message before he met Krämer at 4 o’clock that day.

If Onodera learned in mid-February 1945 that the Soviet Union had committed itself to join the war against Japan three months after the German capitulation, it would have been strange if he had not informed his key collaborator Krämer for whom this information would have been vital. If he had received this information, he would have immediately reported it to Berlin. No such telegram is found among his telegrams in the MUST archive.

Contemporary Statements by Onodera Confirm the Analysis

After 1983, Onodera spoke repeatedly of the Yalta telegram. His claim that he had sent this telegram warning of a coming Soviet attack is contradicted by statements of his that are recorded in wartime documents. They show that he did not believe the Soviet Union would attack Japan—thus confirming the above analysis—except on one occasion when he had good reason to have a different view.

In August 1944, Onodera told the Hungarian assistant military attaché in Stockholm Lázló Vöczköndy with whom he collaborated closely that all of Europe would be exposed to the dangers of Bolshevism after the Allied victory. Having assessed Soviet needs for rehabilitating her industrial and agricultural systems, he was firmly convinced that the Soviet Union would not attack Japan.27 In February 1945, the Home Section received a report from one of its agents that a person in Onodera’s neighbourhood (the name is deleted in the declassified document) was of the same view.28 Onodera also expressed this sentiment on 30 March 1945 to the Finnish intelligence officer Otto Kumenius whom Onodera had recruited as an agent in October 1944. What Onodera did not know was that Kumenius the same month had been recruited as an agent for the Home Section and in early 1945 had also begun to work for the Americans. Kumenius reported to the Office for Strategic Services (OSS): ‘Subject [Onodera] maintained that Russia would never fight Japan but that [a] break between Russia and her Allies was imminent.’29 In mid-April 1945, an agent reported to the Home Section that ‘Onodera’s assistant’ Inoue Yōichi had said Japan was going to continue to fight for another two years despite its knowledge that the United States was eager to attain peace. Inoue was convinced that ‘the Russians will not start a war against Japan’.30 Three weeks later, the Home Section received another agent report that a well-informed source (the identity is masked in the declassified copy) claimed Japan was now concentrating its efforts on not having to capitulate: ‘As the Soviet Union has considerable problems behind its own front, he did not believe that the Soviet Union will enter the war against Japan.’31

The most detailed presentation of Onodera’s view of the Soviet threat is found in a report to the Home Section by an agent who had a meeting with Onodera on 30 May 1945. This agent was most probably Otto Kumenius. He reported that Onodera was

dismissing Europe as completely ruined and facing its inevitable end which, in other words, meant that within two years at the latest Europe would be totally Bolshevized. He explained: England is war-weary and its war industry is unable to work any good; the German war industry is completely ruined and whatever the mighty US war industry manages to produce has to be shipped overseas, which is difficult. […] Russia is now very powerful, which has aroused tremendous nervousness mainly in England. […] France is completely Communist and did not enter the war against the Soviet Union. […] Added to this is the fact that the Soviet Union has the Red Armies from Romania, Bulgaria, Hungary, Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia as well as red Germany. […] Russia will probably not enter the war against Japan, nor has the Soviet Union any interest in running errands for the Allies. Everything the Soviet Union wants to have or achieve the Allies will concede to—His final remark was that the Soviet Union is now very powerful and dangerous. […] Tokio is wholly bombed out, and when I started to talk about it, he shifted to completely different subjects (emphasis added).32

As seen here, Onodera rejected the notion that the Soviet Union would enter the war against Japan in a statement that is strikingly similar to the view he had expressed at the end of March. Thus, Japan’s status as the sole remaining enemy of the Allied powers after Germany’s surrender had not influenced Onodera’s view of the likelihood of a Soviet attack. His general view of the situation was far from alarmist, although he predicted that all of Europe would be ‘totally Bolshevized’. This assertion resembles that which he made to Vöczköndy in August 1944. It also mirrors the message he sent in mid-July 1945 to Japan’s military attaché in Berne, Okamato Kiyotomi, who had asked for Onodera’s ‘views of recent Russian policy (especially vis-à-vis Japan)’. Onodera told Okamoto that the United States and the United Kingdom were in unfavourable positions because they were devoting their national strength to the war against Japan, while ‘Russia is going ahead whole-heartedly with the accomplishment of her plans for the domination of all Europe by means of a political offensive.’33 Nothing is said about a future Soviet attack on Japan. If such an attack was planned, it should be a vital part of the Soviet Union’s Japan policy.34

Another document throws light on how Onodera viewed the Soviet attack on Japan immediately after it had been launched. It came in the form of an interview that the UP news agency had with him. This interview was published in The New York Times on 12 August 1945 and in the Swedish daily newspaper Dagens Nyheter the following day. According to Onodera, peace negotiations sped up because of the dropping of the atom bomb, not because the Soviet Union had entered the war. Thus, in the moment of defeat, he did not place much weight on the Soviet Union’s entrance into the war.

Only on one occasion did Onodera argue differently. Since autumn 1944 two of Onodera’s acquaintances, the Swedish businessman Eric Erickson and Prince Carl Junior, a nephew of the Swedish king, and the two Japanese legation employees Homma Jirō and Satō Kichinosuke had been discussing peace options for Japan. Onodera had flatly rejected joining them. On 7 May 1945, he expressed a change of mind regarding the state of Soviet-Japan relations and his previous refusal to participate in a peace effort that the four had been discussing for months. According to Erickson, the Japanese believed ‘Russia would soon declare war’.35

There were two weighty reasons for Onodera’s shift away from what he is reported to have consistently said before and after 7 May, and they all pertain to this particular day being one of considerable disquiet for him. Firstly, Japan’s ally Nazi Germany capitulated on that day after a long-drawn-out journey towards an apocalyptic end. Secondly, he had just experienced his most devastating personal setback while in Stockholm. In the final moments of the Nazi German regime, Onodera spotted an opening for taking over the German espionage organization in all of Europe and submitted a plan for such an action to the Army General Staff in Tokyo on 1 May 1945. In its response two days later, the Staff disavowed his bold plan (Edström 2021, 205–209). In light of these circumstances, it is not surprising that Onodera should reassess some of his most dearly held convictions. This shift was only momentary, however. He had returned to his previous outlook by the end of the month when the Swedish agent visited him only to find him stating once more that a Soviet attack on Japan was unlikely.

There are no indications in wartime documents that Onodera had informed Tokyo in mid-February 1945 of the Soviet Union’s intention to join the war against Japan three months after the German capitulation. In several cases, he shared information about the Yalta Conference with Krämer, who forwarded it to Berlin, but none of his many telegrams to Berlin brings up anything even remotely similar to what Onodera claimed he had telegraphed to Tokyo. Instead, except for 7 May, Onodera maintained repeatedly during the final year of the war that the Soviet Union was unlikely to join the war against Japan.

Had Onodera perhaps misremembered when this information had reached him? His interrogators at Sugamo were given an account of what happened in the aftermath of Germany’s capitulation. He had received occasional personal letters from Michał Rybikowski in London and two messages from Rybikowski’s superior, Colonel Stanisław Gano. One of Gano’s messages announced the impending Russian declaration of war against Japan.36 However, this information reached Onodera after the German surrender in May 1945— much later than mid-February 1945 when he claimed he had sent the now famous and enduringly elusive telegram.

Concluding Remark

In my search for wartime documents in Swedish and other archives about Onodera’s activities as the Japanese military attaché in Sweden, contemporary documents surfaced that make it possible to give the final word to Onodera himself about the possibility of a coming Soviet attack on Japan. In these documents, it is not the elderly former general pondering over his wartime deeds several decades after the events, but Japan’s eminent intelligence officer who comments on the prevailing situation in the still ongoing war. Onodera is quite outspoken about the low likelihood of a Soviet attack on Japan.

References

‘Agreement Regarding Japan’. 1945. In United States Congress, House Committee on Foreign Affairs. 1953. World War II International Agreements and Understandings Entered Into During Secret Conferences Concerning Other Peoples, 83rd Congress, 1st Session. Washington: Government Printing Office: 30–49.

Dagens Nyheter. 1945. ‘Golfpartier, inga krig, i framtiden’ [Golf parties, no wars, in the future]. 13 August.

Doerries, Reinhard R. 2009. Hitler’s Intelligence Chief Walter Schellenberg: The Man Who Kept Germany’s Secrets. New York: Enigma Books.

Edström, Bert. 2021. Master Spy on a Mission: The Untold Story of Onodera Makoto and Swedish Intelligence 1941–1945. London: Amazon.

Flyghed, Janne. 1992. Rättsstat i kris: Spioneri och sabotage i Sverige under andra världskriget [The crisis of the rule of law: Espionage and sabotage in Sweden during World War II]. Stockholm: Federativ.

Gueldry, Michael R. 2001. France and European Integration: Toward a Transnational Polity? Westport, Connecticut: Praeger.

Kotani Ken. 2012. ‘Interijensu-ofisā to shite no Onodera Makoto’ [Onodera Makoto as an intelligence officer]. Jōhōshi kenkyū 4 (May): 107–117.

Kotani Ken. 2020. ‘Japanese Military Attachés during the Second World War: Major General Makoto Onodera as a Spymaster’. In Defence Engagement Since 1900: Global Lessons in Soft Power, edited by Greg Kennedy, 142–157. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas.

Krebs, Gerhard. 1997. ‘Aussichtslose Sondierung: Japanische Friedensfühler und schwedische Vermittlungsversuche 1944/45’. Viertelsjahrhefte für Zeitgeschichte 45, no. 3 (July): 426–448.

McKay, C.G. 1989. ‘The Krämer Case: A Study in Three Dimensions’. Intelligence and National Security 4, no. 2 (April): 268–294.

McKay, C.G. 1993. From Information to Intrigue: Studies in Secret Service based on the Swedish Experience, 1939–1945. London: Frank Cass.

Okabe Noboru. 2012. Kieta Yaruta mitsuyaku kinkyūden: Jōhō shikan-Onodera Makoto no kodoku na tatakai [The lost emergency telegram about the secret Yalta agreement: The lonely fight of the intelligence officer Onodera Makoto]. Tokyo: Shinchōsha.

Plokhy, S.M. 2010. Yalta: The Price of Peace. New York: Viking.

Pryser, Tore. 2010. USAs hemmelige agenter: Den amerikanske ettertrettningstjenesten OSS i Norden under andre verdenskrig [German secret agents: The US intelligence service OSS in the Nordic countries during World War II]. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

The New York Times. 1945. ‘Japanese Leader sees Sport in War: Gen. Onodera says the Allies should shake Japan’s Hand as if after Tennis Match’. 12 August.

United States Department of State. 1955. Foreign Relations of the United States, 1945, Diplomatic Papers vol. 5: The Conferences at Malta and Yalta 1945. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Yoshimi Masato. 2012. Shūsenshi: Naze ketsudan dekinakatta no ka [A history of the end of the war: Why couldn’t a firm decision be taken]. Tokyo: NHK Shuppan.

Notes

‘Agreement Regarding Japan’. For details on the way in which the agreement concerning Japan in the Yalta Conference came into being, see Plokhy (2010, 222–228).

Ibid. The agreement was released to the press by the Department of State on 8 March 1946. See United States Department of State (1955, 984).

Onodera makes this claim in the Sendai Cadet School Bulletin, Yama murasaki ni mizu kiyoki, 28 (May 1986), quoted in Okabe (2012, 19).

Some contributions to the discussion are Krebs (1997), Okabe (2012), Yoshimi (2012) and Kotani (2012, 2020).

‘German minister, Stockholm, reports impending Soviet rupture with Japan’, Auswärtiges Amt, Berlin, to All Stations, 14 February 1945, HW 12/309, TNA. British decoders sometimes failed to completely decode a telegram and then added their guesses of the non-decoded parts within square brackets. These guesses by decoders have been kept in the quotations.

Otto Danielsson, ‘Krämer-affären’. Promemoria angående förhör med tyske medborgaren Karl Heinz Krämer den 25 mars 1946’, Memo, 3 April 1946, Karl Heinz Krämer, P4478, The archive of the Swedish Security Service (henceforth SÄPO), The Swedish National Archives (henceforth RA), 23.

Strategic Services Unit, War Department, ‘Japanese Wartime Intelligence Activities in Northern Europe’, 30 September 1946, RG 228 Entry 212 Box 5–6, NARA, 28.

‘Uppgift från Utlänningskommissionen betr. Krämers resor’, Karl Heinz Krämer, P4478, SÄPO, RA.

‘Japanese M.A. Stockholm reports on the German Western offensive’, Japanese Military Attaché, Stockholm, to (Summer) Tokyo, Serial No. 244, 21 December 1944, HW 35/75, TNA.

E. Sahlin, ‘Sammanställning av ärendet Hd. 3825/41’, 21 February 1946, Makoto Onodera, P4867, SÄPO, RA.

Note on an index card on Onodera declassified by the CIA, Onodera, Makoto 201-0000047, vol. 1_0007.pdf, CIA, 5; available online at the CIA’s Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Electronic Reading Room (henceforth CIA), accessed 10 June 2020.

‘Löp nr 1, sid 1-100’, and ‘Löp nr 2, sid 101-’, Karl Heinz Krämer, P4478, SÄPO, RA, 53, 97, 114.

‘Three power conference: Japanese minister, Stockholm, forwards agent’s report on the agenda’, Japanese minister, Stockholm, to Foreign Minister, Tokyo, 13 January 1945, HW 12/309, TNA.

‘Betrifft: Dreier Konferenz’, 15 January 1945, Underrättelsetjänst och sabotage. Telegram och meddelanden, FVIIIe, vol. 58, The archive of the Swedish Military Intelligence and Security Service (MUST) (henceforth vol. 58), 169.

‘Betrifft: Sowjetpolitik gegen Japan’ (8 February 1945), vol. 58, 423. The same telegram in Enskilda personer: Krämer, FXf, vol. 86, MUST, 505 lacks the source and the wording and title differ slightly.

‘Betrifft: Drei-Mächtekonferens’, 12 February 1945 vol. 58, 63. The same message, worded slightly differently, is found in Underrättelsetjänst och sabotage. Telegram och meddelanden, FVIIIe, vol. 57, MUST (henceforth vol. 57), 196.

‘Betrifft: Anglo-Amerikanische Luftzusammanarbeit mit Sowjet’ (undated, but sent between 16 and 18 February 1945), vol. 58, 58. This telegram is found also in Karl Heinz Kraemer, KV 2/157:3, TNA, 9. The telegrams before and after are dated 16 February 1945 and 18 February 1945, respectively.

‘Japanese Ambassador, Berlin, reports (1) Interview with Steengracht, (2) Crimea Conference’, Japanese Ambassador, Berlin, to Foreign Minister, Tokyo, Telegram, 15 January 1945, HW 12/309, TNA.

‘Japanese M.A. Stockholm asks for information about Russia’, Japanese Military Attaché, Stockholm to Summer Tokyo, Serial No. 351, 19 February 1945, HW 35/83, TNA.

‘Tokyo replies to questions about Russian strength in the Far East’, Tokyo (NERNS) to Japanese Military Attaché, Stockholm, Serial No. 947, 21 February 1945, HW 35/84, TNA.

Paul Kubala, ‘Brig Gen Makato Onodera, Imperial Japanese Military Attaché, Stockholm’. Seventh Army Interrogation Center, US Army APO 758, 28 May 1945, Ref No SAIC/29, Cornell University Law Library, Donovan Nuremberg Trials Collection, vol. 099, 4. Available online, accessed 18 December 2014.

Agent report, 22 February 1945, Uppgifter om flertal länder, FVIIIe, vol. 53, MUST (henceforth vol. 53), 258. Although the date is not found on the declassified copy, it has been specified by an archive official.

Navy Department Intelligence Report, Serial 12-S-45, Stockh., 7 April 1945, Index Guide, No.101-700, note on an index card on Onodera declassified by the CIA, Onodera, Makoto 201-0000047, vol. 1_0007.pdf, CIA, 8.

Agent report, 17 April 1945, vol. 53, 266. The agent gives only the family name of the assistant, Inoue. He must be the legation official Inoue Yōichi, as he was the only Inoue working at the Japanese legation, see ‘Japanese Intelligence Activities in Scandinavia’, 30 January 1945, RG 263 Entry A1-87 Box 4, NARA, 20. Moreover, no other Inoue left Sweden in January 1946 when the Japanese living in Europe were repatriated, see ‘Passeport Collectif, Collective Passport for a group of Japanese citizens, travelling from Sweden directly to Naples, Italy’, Utlandsrelationer, legationer, personal, JWK 180:0004, Japan, SÄPO, vol. 1994, RA.

Agent report, 10 May 1945, vol. 53, 270. Although the date of the report is not found on the declassified copy, it has been specified by an archive official.

Agent report, 31 May 1945, vol. 53, 277f. It is noted on the document that it deals with ‘General Onodera’. An archive official has confirmed that the speaker is Onodera.

‘Views of Japanese M.A. Stockholm on Russian foreign policy’, Japanese Military Attaché, Berne to Japanese Military Attaché Stockholm, Serial No. 102, 14 July 1945; and Japanese Military Attaché Stockholm to Japanese Military Attaché, Berne, Serial No. 958, 18 July 1945, HW 35/99, TNA.

Eric Erickson, ‘Memorandum–dictated at the American Legation on may 7th 1945’, as reproduced in Eric S. Erickson, ‘Work with OSS Washington 1939–1945’, [n.d., n.p.], Eric S Ericksons arkiv, vol. 4, RA.

‘Interrogation report of General Makoto Onodera (Chapter 6, Polish I.S.; 20 July 1946)’, 10 September 1946, Onodera, Makoto 201-0000047, vol. 2_0016.pdf, CIA, 14.