Abstract: Drawing from the author’s The Opium Business: A History of Crime and Capitalism in Maritime China (Stanford University Press, 2022), this essay explores China’s history as an opium-exporting nation in the early twentieth century. For several decades, southeast coastal China served markets from San Francisco to Manila to Rangoon with illicit opium, morphine, heroin, and cocaine. The essay explains the multiple causes of these developments and argues that this history has been so poorly understood because of its uneasy place within broadly accepted metanarratives about opium, empire, and national victimization.

Keywords: Opium, China, Southeast Asia, Capitalism, Empire

Figure 1: Cover of the author’s The Opium Business: A History of Crime and Capitalism in Maritime China, published in 2022 by Stanford University Press.

The summer heat in the island city of Xiamen can be stifling. Clouds are never above when you want them to be and the stone alleyways work like a labyrinthine kiln to bake overburdened pedestrians. The small islet of Gulangyu across the harbor has offered some reprieve from the hot city over the years: a cool breeze, on the right day. It was neither cool nor breezy, however, for the man hiding from the police in an airless public lavatory on an August afternoon in 1929.

Huang Qing’an had seen them coming and ducked off down an alley, leaving the Shenzhou Pharmacy door swinging open for the Xiamen police, who were out of their jurisdiction in the Gulangyu International Settlement. Huang was a Spanish subject, dating back to that empire’s control over the Philippines, and he was entitled to the protection of a foreign consul. The Xiamen police dragged him from the outhouse, unconcerned with the diplomatic consequences, and ransacked the pharmacy.

The raid produced an interesting haul, but local newspaper reporters and the police department were not sure how to publicize it. Confiscated was about 200,000 yuan worth of opium: 2,280 pounds (1,034 kg) of raw drug from Iran, imported and repacked into oil barrels. There were also several chests filled with paper packets of morphine (on this case, see Nanyang Siang Pau 1929b; IOR 1932; USDS 1929).

This was an impressive seizure, but one that did not fit the narrative. Opium was the scourge of modern China and these police officers had intercepted a substantial shipment of opium—and morphine. The problem was that these drugs were not meant for consumers in China. Huang and his associates were export specialists—people who used their pharmaceutical credentials and connections to supply consumers in Southeast Asia with opium and other drugs. Normally, these schemes were disrupted only in piecemeal seizures on the receiving end, in Singapore, Batavia (now Jakarta), Rangoon, or Manila.

In Xiamen, Huang’s arrest was unprecedented. Opium exporters were never targeted or caught in these decades: state archives and newspapers contain almost no other cases, despite hundreds upon hundreds of seizures in foreign places of opium traced back to Xiamen, many of which are documented in Chapter 5 of The Opium Business.

Also unprecedented: the Chinese police never ferried over to the International Settlement to arrest foreign subjects, no matter which warlord or naval commander was in charge of the city. But Huang’s citizenship offered the Xiamen authorities a loophole: he claimed Spanish protection—a rarity three decades after the Philippines changed hands. The Spanish had long ceased to support a full-time consul in Xiamen, delegating the responsibility instead to a French diplomat, who declined to protest when the Xiamen police charged Huang as a Chinese citizen. The Spanish Consul in Shanghai, when notified, was also uninterested in intervening.

And thus, the Xiamen authorities were free to create the situation they desired. They politely ignored the implications of the evidence that Huang was involved in the export of opium from China, and the details of the case were smoothed over. The police burned the drugs in Sun Yat-sen Park with the standard pomp and ceremony about saving the Chinese nation from the scourge of opium. Misty-eyed onlookers averted their eyes from the wasted high and the lost profits.

Narratives and Evidence

When I set out to research The Opium Business, I understood the basic supply-chain metanarratives about opium in China. In the nineteenth century, British and other merchants brought the drug to China from India. By the 1880s or so, domestic Chinese opium eclipsed British imports, which finally ceased around World War I. In the 1920s to 1940s, opium was still everywhere in China, supplied domestically and through some continued imports, mostly from Iran.

In retrospect, it should have been obvious to me from the outset that the story of opium in China’s Fujian Province would also involve the export of the drug, especially into Southeast Asia. People who make their living studying Southeast Asian history have long understood the significance of China as an illicit opium supplier in the early twentieth century. But in the realm of Chinese history, the export of opium from China has not been a noisy part of the conversation. This is true in part because of a lack of evidence (successful smugglers avoid leaving evidence), but also for the same reason that the Xiamen newspapers and police held back from explaining the full details of the Shenzhou Pharmacy case: the evidence did not fit the narrative.

Figure 2: Southeast Asian Markets for Smuggled Opium from Fujian, 1920s-1930s. Source: Thilly 2022: 152.

As governments across the globe tightened restrictions on opiates in the early twentieth century, the former territories of the Qing Empire came to serve as a crucial source of production and transhipment for opiate consumers across the world, from Southeast Asia to the United States. Whole regions of warlord and Republican China came to be ruled like narco-states, where political and military elites partnered with drug traffickers to monopolize opium’s production and distribution. Local governments repeatedly extended policing and military powers to private opium merchants in exchange for the contribution of crucial finances.

Drug money was imminently attainable: opium was sold through state channels to Chinese consumers, and investors took advantage of a range of smuggling opportunities created by the confluence of jurisdictions and steamer lines. People brought in high-volume cargo that could not make it past the customs in neighboring states, such as Persian opium or Japanese cocaine, and they broke it down and sent it back out in piecemeal quantities. Japanese cocaine destined for Burma and India was packaged, labelled, and transhipped in southeast China. The Persian opium confiscated in the Huang Qing’an case—before it was repacked for export in oil drums—had once been the property of a southern Fujianese ‘Opium Prohibition Bureau’.

The Origins of Opium’s Reverse Course

The opium export business reached its heyday in China during the 1920s and 1930s, but the industry began nearly a century earlier, almost immediately after the drug was legalized in the late 1850s. Opium had been unambiguously illegal in China before the first ‘Opium War’ in the late 1830s, and the treaty that followed that war did not mention the drug or provide any guidance on its regulation. It took about 15 years for a regulatory regime to emerge and, in the late 1850s, the Qing state authorized collection of a range of opium taxes, including a standardized import tax set by British negotiators and a shifting collection of internal transport and distribution taxes.

The import tax was collected by a new foreign-staffed maritime customs service, but to collect taxes on the drug after its import the state leadership opted to try to harness the success of wealthy opium investors. The Qing state pursued the same plan that rulers across maritime Southeast Asia were following: provincial governors would farm out an annual (or multiyear) revenue monopoly to the prominent Cantonese or southern Fujianese (Hokkien) opium merchants who already dominated the trade. It was a plan that had worked for local Southeast Asian rulers, the British, and the Dutch, and it would work in China.

An unintended consequence of this confluence of policies across neighboring regimes was the empowerment of a wealthy and savvy transnational opium investment network. Over the 1860s, 1870s, and 1880s, intense competition raged across southern China and Southeast Asia between the same groups of opium investors, as they either took over state tax farms or slipped into smuggling when the contracts were awarded elsewhere. These were also the decades during which opium cultivation expanded most rapidly across the Qing Empire, producing by the 1880s tens of millions of chests of the drug each year.

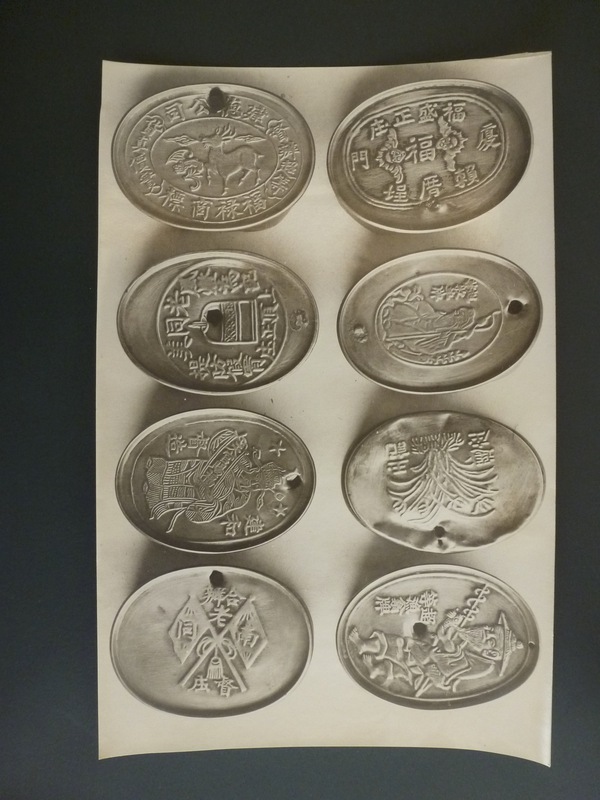

Figure 3: Opium Tins from China Confiscated in the Netherlands Indies, 1930. Source: United Nations Archives at Geneva.

More than enough opium continued to surge into China from India, even as domestic production came to outpace imports. A great many people were doing their honest best to smoke up the drug, but the surplus had to go somewhere. The opium tax farms in places like Singapore and the Netherlands East Indies (now Indonesia) provided the answer: in selling limited brands of the drug at inflated prices, they created openings for migrants from China with access to a greater variety of preparations, at cheaper prices.

By the late 1880s, Singapore newspapers regularly advertised rewards for information about opium smuggling from southern China. It was a constant threat, from the 1880s all the way into the 1930s. As one newspaper article from 1889 argued, the smuggling trend was a product of ‘the extensive coolie immigration and the close commercial connection between Chinese firms and agents in Singapore and the coolie and general trade agencies at these Chinese ports [that is, Xiamen and Shantou]’ (The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser 1889).

It was true: the opium business was expanding through diasporic networks. Most space on the ships arriving in Southeast Asia from China each month was reserved for people, making their way to employment in the colonies. Ports like Xiamen had for centuries served as a point of departure for ships packed with sojourning merchants and laborers bound for Singapore, Batavia, Rangoon, Penang, and Manila. Passenger steamship connections between China and Southeast Asia first launched in the 1870s and, by the first decades of the twentieth century, there were millions of migrants and travelers moving back and forth each year. These were not ignorant people, and a great many came to master the fundamentals of jurisdictional arbitrage. Opium’s export was becoming a major industry, a way for migrants to invest their capital—a capital and logistical connection between diaspora and homeland, and something specifically designed to evade detection.

About the turn of the century, there was a global shift in governance that only served to enhance the profitability of exporting opium from China: prohibition. By the end of the first decade of the new century, nearly every governing body across Asia had restructured its opium regulation and taxation institutions, transitioning from tax farming to a centralized monopoly dedicated to long-term prohibition of the drug. It started in French Indochina and spread from there to the Netherlands East Indies, the British Straits Settlements (now Malaysia and Singapore), Japanese Taiwan, the American Philippine Islands, and through the Qing imperial court in Beijing. There was a fundamental reconstitution of the regulatory landscape and a consequential reconfiguring of the opportunities for profit.

Supply, Demand, and the Networks Between

Tanjung Priok was colonial Batavia’s gateway to the outside world. For the managers of the Dutch Opium Regie, it was one of the most important sites of surveillance and prevention. If they were going to collect revenue on the sale of state opium, they needed to stop the import of illicit opium in places like Tanjung Priok. For opium investors in Xiamen, this was one of a host of locations where a bit of business would be decided. A gambit would either pay off—or not. Drugs would be confiscated or make it through. The courier would be nabbed and do time or collect their reward.

Two poor souls, on 16 March 1925, did not make it through the customs examination of the SS Tjisondari, arriving in Java from Japan via the ports of southern China. The smugglers had used time-honored techniques—probably not for the first time: a couple of reed baskets with false bottoms. They had also hollowed out the sides of a small cupboard. Inside, they had concealed about 10 kilograms worth of small tins of prepared opium, along with some larger, unspecified quantities of raw opium.

The captured smugglers were itinerant merchants from Java: a fish-seller and a fried noodle (bami) chef—both categorized as ethnically Chinese by the Dutch State. They testified on their arrest that they had paid $100 (in silver) down to merchants in Xiamen for the opium, and they were to remit the balance after selling the drug at its destination in Surabaya. The opium was so cheap in China, they would still have been able to sell it under monopoly prices in the Netherlands East Indies after smuggling it across the ocean and down the length of Java (LON 1925).

When the two luckless peddlers from Java visited in 1925, the city of Xiamen was a buyer’s market for opium investors interested in testing the Southeast Asian smuggling waters. The drug was fully commodified and commercialized and the port city hosted a more sophisticated marketplace than when opium had been fully legal. There were dozens of brands of tinned opium paste available for export (USDS 1921). Many of these companies sourced their opium locally, like the Stork, Deer, and Fig Tree & Deer brands. These brands marketed small, 1-tael (38 g) tins of opium that could be purchased in Xiamen for between three and four silver dollars. They were routinely confiscated by customs in ports from Singapore to San Francisco. The Unicorn and Two Peach brands also sold local Fujianese opium and were clandestinely exported to the Straits Settlements, the Philippines, French Indochina, and parts of northern China. The luxury Cock brand of opium paste—the ‘most famous on the market’—was boiled down from the port’s last remaining stocks of Benares opium imported from Calcutta. It had also inspired local knockoffs—one using Yunnan opium and another drawn from opium cultivated locally in southern Fujian. These, too, were unearthed by customs and police officers wherever the Fujianese diaspora had achieved a foothold, from Rangoon to California.

The two smugglers from Java visited Xiamen when the city was under the control of a naval commander named Yang Shuzhuang. Opium was not technically ‘legal’ under Yang’s regime, but he collected $20,000 a month from an ‘Opium Prohibition Bureau’ that was operated by opium investors in the city’s chamber of commerce. Licensed state opium dens lined the city streets. Meanwhile, other powerful officials including the military governor in Fuzhou collected millions of dollars’ worth of ‘poppy taxes’ in several of the counties neighboring Xiamen. This, too, was a branch of revenue farmed out to investors. The people who purchased contracts to collect the poppy taxes were usually businessmen from the port city who would send armed officers out to collect the opium at harvest time, taking the allotted ‘poppy tax’ out of each family’s remuneration for growing the drug. There were some truly massive harvests in those years.

Prohibition and Recrudescence

When the Qing court announced its prohibition plan in 1906, there was not an enormous amount of optimism involved. Still, few would have had the cynicism to predict just how much the opium trade would expand and entrench itself at the nexus of state power over the subsequent two decades.

The explanation for this is necessarily multi-causal. British recalcitrance in helping the Qing prohibitionists stands in stark contrast to the ready cooperation afforded to the US Philippine Islands when that government requested the British cease imports of Indian opium. The fall of the Qing regime and the fragmented nature of governance during the Republican era (1911–49) created opportunities for regional variation and fostered the emergence of key narco-regions like Yunnan (production), Hankou (transhipment), Shanghai (transhipment and export), and Fujian (production, transhipment, and export).

One of the only constants during these tumultuous years was that opium money was fast and ready. Rural officials could do a lot more with a poppy tax than a standard land tax, and farmers in many locations preferred the cash crop. Urban officials were asked to sacrifice their opium retail and distribution taxes just as the concept of a ‘prohibition bureau’ was introduced: a state monopoly on opium—a potential cash cow. Decisions were made, over and again, to farm out the operation of prohibition bureaus to the people with a demonstrated capacity to buy and sell large quantities of opium. Jaw-dropping cash payments litter the records: millions upon millions each year in prohibition bureau contracts and poppy tax collections.

The minor warlord Ye Dingguo of Tong’an County, to name just one bit-player of the era, was reported in the Singapore press to have amassed $45 million in 1932 through a combination of poppy taxes and distribution monopolies. Chen Guohui, who controlled large areas of Quanzhou and Yongchun prefectures between 1929 and 1932, imported huge shipments of poppy seeds from Burma to better facilitate a lucrative harvest when he took over the region. On the eve of his eviction by the Nineteenth Route Army in late 1932, Chen’s personal wealth had grown to an estimated $66 million (Nanyang Siang Pau 1932). How many tins of opium packed under the oversight of these two men passed secretly into Singapore, Java, or Manila?

The Modern Chinese Narco-State

All this shows that the history of the Chinese opium export industry is fundamentally transnational: it was a branch of international trade that evolved in response to political developments across a host of nations and jurisdictions. The market persisted in colonial Southeast Asia in no small part because of the very slow path that opium monopolies took towards long-term reduction in opium use. In some locations, opium monopolies accounted for as much as 50–60 per cent of state budgets in the late 1910s and continued to cash in well into the 1930s even as the other state representatives were reaching a global consensus on prohibition (Kim 2020: 234). States were still encouraging people to smoke opium and the people travelling between jurisdictions noticed and took advantage.

In China, opium supplies skyrocketed over the first three decades of the twentieth century. Nearly every regional and national government in those years operated an opium monopoly to supplement military and administrative budgets. In Fujian, the earliest ‘prohibition bureaus’ took over existing institutions and systems of opium den registration, classification, and taxation. Like the nineteenth-century tax farms in Fujian and Southeast Asia, these agencies were contracted out to coalitions of wealthy opium investors seeking an edge over their competitors. Together with their business partners, the Nationalist Party (Guomindang) and warlord rulers of Fujian after 1911 embedded opium tax farming within the modern Chinese State. In so doing, they ensured an unceasing supply of the drug would continue to be produced and sold.

And so, just as a new global consensus was beginning to awaken to the notion that China had been victimized by the opium trade, the fragmented former Qing Empire began to assume a new role as an illicit exporter of opium, morphine, and cocaine into the British, Dutch, and US colonies of Southeast Asia. Opium’s reverse course: when British and other colonial administrators were moved to clutch their pearls about the unlawful introduction of Chinese opium into their jurisdictions. The irony would be more satisfying if the historical power dynamics were not so ugly.

References

IOR/R/20/A/3495, File 963, ‘Report on the Investigation of the Problem of Smuggling Cocaine into India from the Far East’, 1932.

Kim, Diana. 2020. Empires of Vice: The Rise of Opium Prohibition Across Southeast Asia. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

LON 1919–1927: Box R766, Sec 12A, Doc 45811, Dossier 24287: Seizure of Raw Opium at Tanjoengpriok, 16 March 1925.

Nanyang Siang Pau. 1929a. ‘駭人聽聞之閩省匪軍官長之資產 [Frightful News about the Personal Wealth of the Bandit Warlords in Fujian].’ Nanyang Siang Pau [Nanyang Business Daily], 28 June: 14.

Nanyang Siang Pau. 1929b. ‘鼓浪破獲大宗煙土 [Authorities Confiscate Large Amount of Opium on Gulangyu].’ Nanyang Siang Pau [Nanyang Business Daily], 6 September: 10.

Nanyang Siang Pau. 1932. ‘駭人聽聞之閩省匪軍官長之資產 [Frightful news about the personal wealth of the bandit warlords in Fujian].’ Nanyang Siang Pau [Nanyang Business Daily], 28 June: 14.

The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser. 1889. ‘Saturday, October 5, 1889.’ The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 7 October: 426.

Thilly, Peter. 2022. The Opium Business: A History of Crime and Capitalism in Maritime China. Redwood, CA: Stanford University Press.

USDS 1910–29, 893.114/293, Reel 114, Xiamen to Secretary of State, 30 April 1921.

USDS 1910–29, 893.114 Narcotics/68, Reel 116, Xiamen to Secretary of State, 4 September 1929.