Abstract: At the turn of the twentieth century, Euro-American colonialism remade the lives of thousands of Samoan, Melanesian, and Chinese workers on coconut plantations in Samoa. Since plantation discipline was strict, workers resisted the heavy demands on their bodies through a broad arsenal of behaviors, ranging from keeping crops for themselves to making appeals to the state to waging violent attacks on overseers. Resistance against colonial subjection turned workers in Samoa into subjects of their own lives and allowed them to forge bonds of solidarity beyond the spatial, social, and racial boundaries maintained by colonial administrations. In doing so, Samoa’s workers shaped their own version of Oceanian globality.

Keywords: China, Samoa, Capitalism, Labor, Colonialism

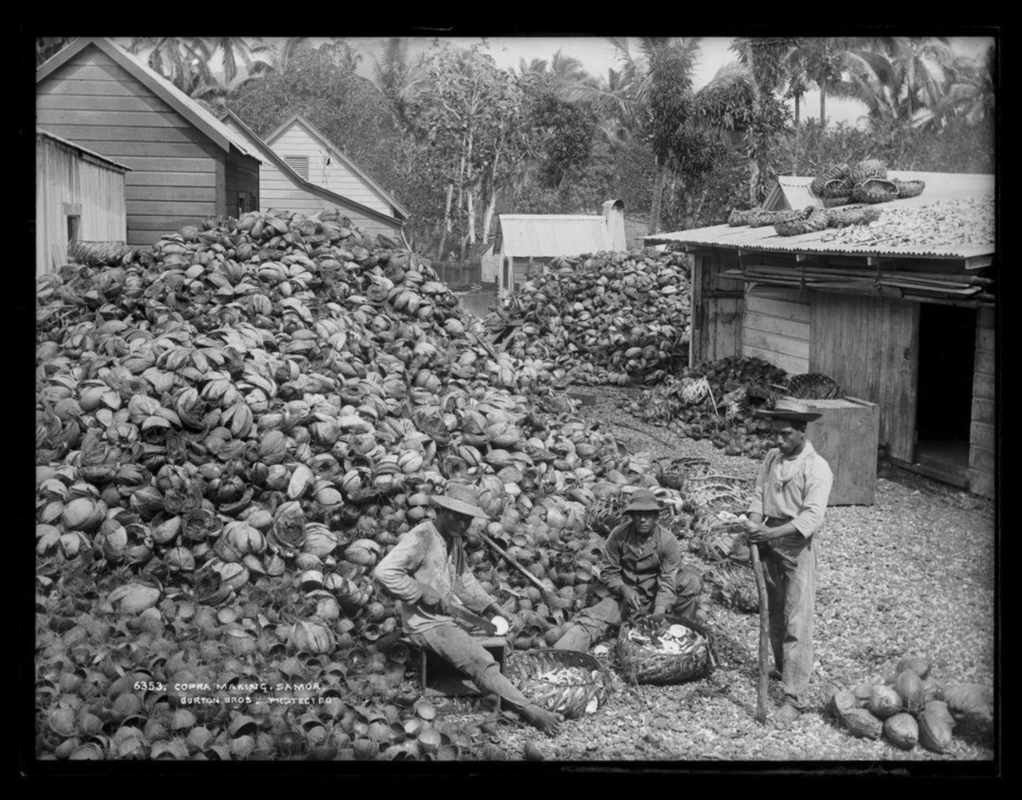

Figure 1: Copra making, Samoa. Source: Museum of New Zealand / Te Papa Tongarewa.

In April 1904, Ko Tuk Shung was confronted by a group of angry plantation workers from China. As personal servant of the Governor of German Samoa and interpreter at the Imperial Court, Ko Tuk Shung was one of the most influential Chinese living in the colony. The workers wanted his advice in a delicate matter. Their boss, the German plantation owner Richard Deeken, had complained that cash money and vegetables had been stolen on his two-thousand-acre cacao plantation in Tapatapao, a few miles south of Apia. When the thefts remained unresolved, Deeken had decided to punish his Chinese workers by cutting their wages. The outraged workers demanded to know from Ko Tuk Shung if Deeken had the right to do so. Unsure himself, Ko Tuk Shung in turn asked his employer, Governor Solf, who replied that the laborers could make a complaint in the German Imperial Court. But before Ko Tuk Shung could pass on Solf’s suggestion, the workers decided to take matters into their own hands and composed a letter of complaint against Deeken, accusing him not only of withholding their wages but also of repeatedly humiliating and beating them. In a gesture of social deference, they then asked their Chinese overseer, Ah Tsung, to forward their letter to the court.

In the letter, the workers defended themselves against Deeken’s accusations by pointing out that “after a good hard day’s work we feel more inclined to lay down and have a good rest instead of roaming about at night to steal things from our own master’s house.”1 When Deeken found out that his overseer had assisted the workers’ protest, he set out to punish Ah Tsung, probably because he could not imagine his own workers to be savvy and courageous enough to file a complaint on their own. Past midnight on April 28, four Chinese laborers carried Ah Tsung on a stretcher to the colonial administration building in Apia. There, Imperial Doctor Dr. Julius Schwesinger confirmed that Ah Tsung had been severely whipped and had suffered heavy injuries on his face and arms. As court investigations revealed, Deeken had hit Ah Tsung with a “dangerous tool”—a leather whip—and “in blind anger” had tried to hit him “wherever he could”. Ah Tsung eventually recovered from his life-threatening wounds. In June 1904, the Imperial Court sentenced Deeken to four months in jail for physically abusing his overseer.2

Deeken’s trial revealed the realities of plantation life in German Samoa—a world of broken contracts, physical violence, and organized resistance by Chinese workers. Relying on their close personal links, Chinese workers in German Samoa used an underground communication line that stretched from Deeken’s plantation all the way to the Governor’s kitchen. Chinese workers shared information and organized collective action across workscapes. By making public what should have remained secret, Ah Tsung and his fellow Chinese workers had challenged the colonial order of things. And in the end, the workers succeeded in bringing Deeken’s abuses to light, paving the way for future resistance against violent plantation owners.

As plantations remade the lives of thousands of Samoans, Melanesians, and Chinese, this diverse group of workers carved out precarious livelihoods in the new world of copra. Since work discipline on plantations was strict, workers resisted the heavy demands on their bodies through a broad arsenal of behaviors, ranging from keeping crops for themselves to making appeals to the state to waging violent attacks on overseers. Resistance against colonial subjection turned workers in Samoa into subjects of their own lives and allowed them to forge bonds of solidarity beyond the spatial, social, and racial boundaries maintained by colonial administrations. In doing so, Samoa’s workers shaped their own version of Oceanian globality.

The People Trade to Samoa

Throughout the nineteenth century, Samoans continued their sustainable farming practices in the face of increasing outlander pressure on their land and labor. Under its paternalist veneer, Governor Solf’s salvage colonialism was an acknowledgment that the economic, political, and military strength of Samoans made forced labor impossible. As a consequence, plantation owners had to turn elsewhere for their labor supply. In the 1860s, Godeffroy had built its trading empire in the South Pacific by recruiting laborers mostly from the Gilbert Islands (part of Kiribati). Beginning in the late 1870s, contract workers also came from Bougainville and the Bismarck Archipelago in New Guinea, from the New Hebrides (Vanuatu), and from Malaita in the Solomon Islands.3 Located between Samoa and the Godeffroy trading stations in the Marshall Islands, the Gilbert Islands offered an ideal recruiting pool for company ships on their way back to Apia. More importantly, regular and severe droughts on these low-lying coral atolls forced their inhabitants to seek alternative means for survival, including contract labor in Samoa, Fiji, and Tahiti.4 Unlike other Pacific Islander contract laborers at the time, most Gilbert Islanders went to Samoa in family groups, which made them even more attractive to Godeffroy because women and children were better at picking and weeding and could be paid less.5 By 1885, a total of nearly 5,000 Pacific Islanders—almost half from the Gilbert Islands—had been recruited to Samoa, most of them by the powerful German trading firm, the Deutsche Handels- und Plantagengesellschaft der Südseeinseln (DHPG).6

The DHPG maintained exclusive access to laborers from Melanesia into the years of formal German rule (1900–14)—a crucial basis for its business success.7 Other plantation owners, especially newcomers with little seed capital, took offense at this competitive advantage for the biggest economic player in German Samoa. To circumvent the labor monopoly of the DHPG, smallholders, led by Deeken, pushed the colonial government to recruit contract laborers from China.8 Earlier regulations passed by Samoan leaders and Euro-American diplomats in the 1880s had explicitly prohibited the recruitment of Chinese workers, as the powerful DHPG, with its labor monopoly in Melanesia, opposed the import of Chinese workers by its smaller competitors. In the end, however, the new settlers prevailed. After months of difficult negotiations between a German agent and local authorities in Shantou, the first transport of 300 Chinese contract workers arrived in Apia in April 1903. Since Chinese laws prohibited the emigration of contract laborers, the Chinese recruits signed their labor contracts only after they had boarded the steamer in Hong Kong.9

In German Samoa, the Chinese workers took up a number of jobs. Most worked on plantations cutting copra, overseeing fellow workers, and cooking. Others chose domestic work or helped the colonial administration build roads and docks. A handful of the new arrivals from China worked as traders, bakers, tailors, and box-makers. From the beginning, Euro-American traders feared competition by their Chinese counterparts and called on the administration to withdraw their licenses—with limited success.10 Between 1905 and 1913, six additional transports brought a total of almost 4,000 Chinese workers to Samoa.11 Contract workers had to spend most of the three-week journey from mainland China to Samoa on bunk beds in the hot and stuffy holds of the ships.12

Chinese labor migrants, most of them young men, had a long and complex history of movement and settlement throughout the Pacific world, dating back to at least the sixteenth century.13 Tens of thousands of Chinese men worked on plantations in the Dutch East Indies, Malaya, Queensland, Hawaiʻi, and as far as the Caribbean, enduring the hardships of exhausting work for little pay and even less legal protection.14 With their meager earnings, workers helped support their families back home in China.15 The Chinese workers who had filed a complaint against Deeken in 1904 had stressed family remittances as one of their main motivations to come to Samoa: “We are very poor and have come all the way from China to earn a little money for the maintenance of our aged parents and relatives in China who are exceedingly poor.”16 Beginning in the first decade of the twentieth century, Chinese labor migration to Samoa constituted a small yet consequential episode in this global story.17 Resilient and enterprising, the first generation of Chinese workers who stayed on the islands laid the foundations of a dynamic Chinese-Samoan community still present today.18

The recruitment and treatment of workers on Samoan plantations were shaped by racial hierarchies of labor. While Melanesians did most of the unskilled, hard physical labor, some Chinese recruits also performed skilled tasks, such as tapping rubber trees.19 In contrast to Samoans and other Pacific Islanders, Chinese workers were generally portrayed as obedient, experienced, and hard-working plantation workers. Plantation owners and colonial officials used racial stereotypes to divide workers and make them more productive, but their identities remained in flux. As the migrants on Samoan plantations came to see themselves more and more as New Guineans, Solomon Islanders, and Chinese, they also forged affective ties with fellow workers. And if colonialism and capitalism limited the ways in which places like Samoa related to the wider world, the islands’ diverse inhabitants found creative ways to transcend these constraints.

Resisting Plantation Discipline

While plantation owners had a vested interest in getting as much labor out of their workers as possible, workers carved out moments of freedom under this oppressive system. In early 1906, for example, 400 Chinese workers banded together and sent a letter to the Chinese Embassy in Berlin, by way of Honolulu and Washington, to complain about their working conditions. In their petition, the workers wrote about the cruel treatment they faced on German plantations and asked for an official to be sent to Samoa to protect them.20 Later that year, more than 60 Chinese workers on Deeken’s plantation in Tapatapao struck in protest against a cruel overseer, while some Chinese workers even committed suicide.21 Apparently, conditions for Chinese workers on Samoan plantations had not improved since Deeken’s conviction in the summer of 1904.

Outraged at these and other abuses, the Chinese Government sent a special commissioner to German Samoa to represent the Chinese workers. In March 1908, commissioner Lin Shu Fen arrived in Apia to investigate the work conditions on the islands.22 Touring the plantations, Lin Shu Fen caused quite a stir among German plantation owners and colonial officials. At the end of his month-long visit, Lin Shu Fen confirmed the allegations made by the workers about their cruel treatment and sent a damning report back to China.23 The following year, a second official, Lin Jun Chao, visited the plantations and reached similar conclusions. Lin recommended a series of reforms, including the abolition of flogging and identification badges, and called for better food for the workers.24

In contrast to their fellow workers from Melanesia and Micronesia, Chinese workers thus came to enjoy legal protection and political support from their home government. In May 1911, Chinese in German Samoa achieved legal status equal to Euro-American settlers.25 And by 1913, the German colonial administration had met most of the Chinese calls for legal equality and better working conditions.26 Starting in the 1890s, Chinese officials had implemented policies to protect overseas Chinese communities and attract migrants back to their homeland. These efforts by Qing officials intensified after the Republican revolution in 1911. German Samoa emerged as one of the test cases for Chinese nationalist agitation.27 On May 28, 1912, Lin Jun Chao, who had been promoted to Chinese consul, informed his U.S. colleague in Apia that China had become a republic and that the new national flag would be flown from the consulate starting June 1.28 Political change at home, however, went beyond mere symbolism for the Chinese workers in German Samoa.

While the majority of Chinese workers at the time were technically “free” migrants who signed labor contracts upon arrival in Southeast Asia and other parts of the Pacific world, German plantation owners recruiting Chinese workers to Samoa could simply not afford this legal nicety. Together with the lack of a Sino-German treaty regulating the emigration and employment of Chinese workers in German territories, this impression of “coolie labor” fueled opposition by the Chinese Government.29 Combined with a desperate need for workers among new plantation owners in Samoa, legal and political protection by their home government gave Chinese workers a powerful avenue for redress and generally made them less vulnerable to excessive punishment. As Melanesian workers later recalled, better legal protection directly translated into better living conditions for Chinese workers.30

In August 1914, New Zealand occupied German Samoa. For Chinese workers, the transfer of power from one empire to another did little to change the poor living conditions they confronted. Conflicts over withheld and reduced wages continued throughout World War I. As in other areas, the new rulers from New Zealand maintained the German labor regulations.31 Recruitment of new workers from China and Melanesia came to a halt during the war as German plantations were expropriated. The new military governor Robert Logan’s then moved to repatriate Chinese plantation workers. Influenced by widespread fears of the “yellow peril”, Logan began sending Chinese workers back home. Between 1914 and 1920, over 1,200 Chinese workers returned to China without being replaced.32

Hunger pushed Chinese workers to outright rebellion. Since the outbreak of the war, Euro-American plantation owners had put their Chinese workers on short rations for fear of a large-scale rebellion. Logan did nothing to change that.33 In late August 1914, hundreds of Chinese workers left their plantations and came to Apia to protest against the reduced rice rations.34 Following Logan’s orders, Samoan policemen set out to quell the rebellion and started clubbing the Chinese workers. According to a New Zealand soldier who witnessed the brutal suppression of the Chinese rebellion, the Samoan policemen “used their batons freely and blood flowed.”35 Several Chinese were beaten up so severely that they had to be treated in the hospital. One of them later died of his injuries.36 The following May, Logan issued an ordinance that punished the exclusively Chinese crime of “loafing” with a fine of up to 30 shillings ($7.50).37

The mass repatriation of Chinese and Melanesian workers combined with a horrific flu epidemic to create a large-scale labor shortage on Samoan plantations. Copra production peaked in 1917, but then nose-dived as workers left the islands.38 At war’s end, a copra boom intensified the labor shortage. Beginning in August 1920, the New Zealand administration reversed its policy of repatriation and started recruiting new Chinese workers. The flu epidemic that had killed over a fifth of the Samoan population had also destroyed plans to force Samoans onto plantations. Between 1920 and 1934, eight new transports brought a total of over 3,000 Chinese workers to Samoa.39

Gradually, the most severe labor regulations were dismantled, culminating in the abolition of contract labor itself in 1923.40 Labor protests, however, continued. In August 1929, 300 Chinese workers went on strike over the failure to resolve a dispute over their foremen. A dozen Chinese strikers received gunshot and baton wounds when the New Zealand police attacked them.41 Only a few months later, the police used similar methods to suppress a demonstration by the Samoan Mau movement that challenged colonial rule. In many ways, the “weapons of the weak” pioneered by plantation workers since the 1880s had helped prepare the ground for this fundamental challenge to colonial rule.42

Beyond Coconut Colonialism

In colonial Samoa, the most effective forms of resistance against coconut colonialism emerged out of attempts to transcend the division of labor. Workers who moved between workscapes were in the best position to challenge the demands of the colonizers. Chinese plantation workers knew that a handful of fellow migrants to Samoa were employed in other occupations such as cooking and interpreting. When a group of Chinese workers filed a petition protesting the cruelty of their German plantation owner, they had consulted with the Governor’s personal cook and Chinese interpreter at the Imperial Court. By making connections across workscapes, workers in Samoa exposed the interdependence of different kinds of labor and were better able to resist exploitation. From plantations to the Governor’s office, workers in Samoa used the particular dynamics of their workscapes to imagine an Oceanian future beyond coconut colonialism.

Even today, Samoa’s future remains deeply linked to East Asia and especially China. With its heavy dependence on remittances and foreign aid, Samoa is hoping to diversify its economy and attract more tourists, from China and elsewhere. The first Chinese contract laborers who arrived in Samoa over a century ago would have a difficult time recognizing today’s Pacific world. One of their descendants, Fred Wong, did not forget these early pioneers. In an interview, he said: “Who knows where Samoa would be today were it not for those thousands of ‘coolies.’ I am sure we owe them a debt of gratitude.”43

Read more in the author’s book, Coconut Colonialism: Workers and the Globalization of Samoa (Harvard University Press, 2022).

Notes

Solf to District Judge, Apr. 10, 1904, ANZ Wellington, SAMOA-BMO Series 4, Box 73, T40/1904, Vol. 1, p. 3.

The first 81 Gilbertese Islanders were forcibly recruited in 1867. Doug Munro and Stewart Firth, “Samoan Plantations: The Gilbertese Laborers’ Experience, 1867-1896,” in: Plantation Workers: Resistance and Accommodation, edited by Brij V. Lal, Doug Munro, and Edward D. Beechert (Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 1993), 102-03.

By the late 1870s, men received $2 per month, usually payable in tobacco, plus rations, while women and children made $1. Ibid., 123 n18.

Of the total 4,857 workers, 2,250 were from the Gilbert Islands (46%), 1,201 from the New Hebrides (25%), 693 from New Britain and New Ireland (14%), 618 from the Solomon Islands (13%), and 95 from the Caroline Islands (2%). Stübel to Bismarck, Jan. 27, 1886, BArch R 1001/2316.

During the years of German rule in Samoa, the DHPG paid out an average dividend of 21%. Stewart Firth, “German Recruitment and Employment of Labourers in the Western Pacific before the First World War” (PhD thesis, University of Oxford, 1973), 242.

For a succinct summary of the debates about importing Chinese workers to German Samoa, see Stewart Firth, “Governors versus Settlers: The Dispute over Chinese Labour in German Samoa,” New Zealand Journal of History 11, no. 2 (1977): 155-179.

Nancy Tom, The Chinese in Western Samoa, 1875-1985: The Dragon Came From Afar (Apia: Western Samoa Historical and Cultural Trust, 1986), 36.

Philip A. Kuhn, Chinese Among Others: Emigration in Modern Times (Lanham, MA: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2008); Ching-Hwang Yen, Coolies and Mandarins: China’s Protection of Overseas Chinese during the Late Ch’ing Period, 1851-1911 (Singapore: Singapore University Press, 1985).

Walton Look Lai, “Asian Contract and Free Migrations to the Americas,” in: Coerced and Free Migration: Global Perspectives, edited by David Eltis (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2002), 229-58.

Overall, family remittances by Chinese workers in Samoa remained relatively low. In 1912, they amounted to 7% of total wages paid. Cf. Hermann Hiery, ed., Die Deutsche Südsee 1884-1914: Ein Handbuch (Paderborn: Ferdinand Schöningh, 2001), 672.

Solf to District Judge, Apr. 10, 1904, ANZ Wellington, SAMOA-BMO Series 4, Box 73, T40/1904, Vol. 1, p. 3-4.

Adam McKeown, Chinese Migrant Networks and Cultural Change: Peru, Chicago, Hawaii, 1900-1936 (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2001), esp. chapter 2; see also, his Melancholy Order: Asian Migration and the Globalization of Borders (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2008).

Ben Featuna’i Liua’ana, “Dragons in Little Paradise: Chinese (Mis-) Fortunes in Samoa, 1900-1950,” The Journal of Pacific History 32, no. 1 (1997): 29-48; A.S. Noa Siaosi, “Catching the Dragon’s Tail: The Impact of the Chinese in Samoa” (M.A. Thesis, University of Canterbury, NZ, 2010).

Evelyn Wareham, Race and Realpolitik: The Politics of Colonisation in German Samoa (Frankfurt/M.: Peter Lang, 2002), 111.

Andreas Steen, “Germany and the Chinese Coolie: Labor, Resistance, and the Struggle for Equality, 1884-1914,” in: German Colonialism Revisited: African, Asian, and Oceanic Experiences, edited by Nina Berman, Klaus Mühlhahn, and Patrice Nganang (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2014), 152.

Lin to Mitchell, May 28, 1912, NARA-CP, RG 84, Vol. 77. As Lin did not fail to mention a year later, the United States officially recognized the new Chinese Republic on May 2, 1913.

Malama Meleisea, O Tama Uli: Melanesians in Western Samoa (Suva, Fiji: University of the South Pacific, 1980), 42.

Felix M. Keesing, Modern Samoa: Its Government and Changing Life (London: G. Allen & Unwin, 1934), 301.

Michael Field, Mau: Samoa’s Struggle Against New Zealand Oppression (Wellington, NZ: Reed, 1984), 13.

Hermann Hiery, The Neglected War: The German South Pacific and the Influence of World War I (Honolulu, HI: University of Hawai’i Press, 1995), 167.

Robert W. Franco, Samoan Perceptions of Work: Moving Up and Moving Around (New York: AMS Press, 1991), 152.

James C. Scott, Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1985).