Abstract: This paper traces the history of Ryōzen Kannon, a little-known religious site in Kyoto, Japan, to consider war memorials as sites of transwar continuity and change, and as ideological tools to present certain visions of past and present wars. While Ryōzen Kannon is promoted today as little more than a typical Japanese temple, it has a remarkable history beginning in the 1950s with its establishment by the business entrepreneur Ishikawa Hirosuke. Opened in 1955, it was pitched as a Buddhist alternative to commemorating the patriotic sacrifices of the war dead. Shortly thereafter, a separate monument to Allied prisoners of war that professed world peace and reconciliation was added to the site. While accompanied by historically valuable records of these former prisoners, however, this monument was largely a homage to the Cold War-era Japan-US alliance, and it obfuscated memories of violence in East Asia from the site. Since the 1960s, Ryōzen Kannon has struggled to keep up with the times. Particularly after the death of its founder and the end of the Cold War, the site has become increasingly anachronistic. Now, it occupies an ambiguous space between remembering and forgetting.

Keywords: Ryōzen Kannon, Ishikawa Hirosuke, Kyoto, war memorials, war dead, Asia-Pacific War, Cold War, Yasukuni Shrine

Introduction

Business magnate Ishikawa Hirosuke (1891–1965) built Ryōzen Kannon in Kyoto, Japan in 1955 as a Buddhist memorial to the nation’s war dead of the Asia-Pacific War (1931–1945). It is dominated by an early example of a modern, large-scale statue of Kannon, the bodhisattva of benevolence and mercy, which were instrumentalized as war memorials throughout Japan during and after the war (Kimishima 2019). Ishikawa founded the site to commemorate soldiers of the former Imperial Japanese Army and Navy as well as Japanese civilians, and later added a separate memorial dedicated to Allied Second World War prisoners of war (POWs).

Though its architecture and services are overtly Buddhist, Ryōzen Kannon was not initially an official religious site. A few months after its construction, Ishikawa formed the Ryōzen Kannon Kai (henceforth, RKK) to maintain Ryōzen Kannon and direct new projects. Two years later, maintenance was ceded to the newly established Ryōzen Kannon Church, making it a registered religious corporation (Ōru Teisan 1974). This official status helped provide further legitimacy as a religious site, as well as tax benefits and new sources of income through religious services. Ishikawa designated it as a “church” (kyōkai)—a term used more commonly for Christian or new religious than Buddhist places of worship—to make it non-denominational, thus enabling the memorialization of a wide range of people. This continues today in the running of services by monks from various sects of Buddhism. Of the five current monks, one is affiliated with each of the Tōfuku-ji and Kennin-ji branches of Rinzai, the Ōtani and Kibe branches of Jōdo Shinshū, and the Shingon sect (personal communication with temple, 20 January 2022). Additionally, the ossuary hall (nōkotsu-dō) and memorial services are provided regardless of the religion, sect, and nationality of the deceased. This non-denominational orientation may have also facilitated the expansion of Ryōzen Kannon’s memorialization scope beyond Japan’s war dead.

Ryōzen Kannon’s name combines that of the nearby Mt. Ryōzen—originating from Gádhrakúta, a mountain in northern India deeply associated with the historical Buddha, Siddhartha Gautama—and the 24-meter-tall reinforced concrete statue of Kannon, which dominates the site’s grounds. Larger than the 15-meter-tall Great Buddha of Tōdai-ji temple, when built this statue would likely have been the tallest statue in the Kansai region. Its design is based on a 13th century painting of Kannon held at Kyoto’s Daitoku-ji temple and was the last work of renowned sculptor Yamazaki Chōun (1867–1954) (Ōru Teisan 1974). As reflected in its size and central, elevated location above the main hall (figure 1), the statue is the primary focus of the site and an eye-catching attraction. It overlooks the surrounding area, has a tranquil countenance and feminine facial features accompanied by a hollow “inner womb” (tainai) into which people can enter. Ryōzen Kannon is thus designed to project an aura of solemnity and calm and symbolize motherlike compassion and guardianship over the dead. This symbolism draws on the millennia-long year history of the cult of Kannon in Japan and its continental Asian origins, including Kannon statues memorializing the war dead that were constructed during the Second Sino-Japanese War (Kimishima 2019).

Figure 1: Ryōzen Kannon (photo by David Moreton, 2017).

In addition to the Kannon statue, the grounds of Ryōzen Kannon contain several monuments and records significant to war memory in Japan and beyond. Firstly, it holds a register with the names of two million Japanese war dead. Behind the statue and main hall, which acts as a space for services and gatherings, sits the Reihaiden, a hall with 600,000 small Buddhist tablets (ihai) for Japanese and others who died in the Asia-Pacific War, including—as will be explored later—Koreans. Both the register and collection of ihai tablets are from the early years of Ryōzen Kannon. Adjacent to the Reihaiden is the Memorial Hall, which was built in 1959 to house a monument to the unknown soldier.1 This also contains vessels of soil from war cemeteries around the world and cabinets containing records of the names and fate of tens of thousands of Allied POWs who died in Japanese captivity between 1941 and 1945.

Research about Ryōzen Kannon and Ishikawa has only begun to reveal the site’s significance to Japanese transwar and international war memory. Tachibana Naohiko (2011) explored how Ryōzen Kannon incorporated a building planned, but never used, as a Buddhist ossuary hall by the local 16th Division of the Army. David Moreton (2018) examined the history of Ishikawa and the POW records housed in the Memorial Hall. Meanwhile, Kimishima Ayako (2019) placed the statue within the context of a construction boom in large-scale statues of Kannon, which in the early period between the 1930s to 1950s were primarily built as landmarks commemorating war dead, then later as symbols of postwar peace and prosperity. For Kimishima, Ryōzen Kannon combined religious commemoration of war dead with tourism. Sven Saaler (2020) examined a statue that Ishikawa constructed in 1940 of the eighth century court official Wake no Kiyomaro as a site of wartime nationalism. Previous research, however, has not fully investigated the significance of Ryōzen Kannon in war memory, critically scrutinized its geopolitics, nor explained its rise and fall in popularity.

As Ishikawa does not seem to have made many public pronouncements about his political convictions, but rather let his public monuments speak for themselves, Ishikawa’s monuments at Ryōzen Kannon and elsewhere provide insights into him as an agent of memory. Previous studies focus on Ishikawa’s monuments from either the wartime or postwar periods, and thus fail to perceive him as a unique and important actor who sought to help shape public memory both during and after the Asia-Pacific War. This paper addresses these gaps by analyzing the history of Ryōzen Kannon, from its founding by Ishikawa up to its present status, and through this highlights the importance of Ryōzen Kannon as a site of transnational memory.

Studies of memorials for the war dead in Japan have explored them as important sites of local, national, and transnational war memory and politics. Memorials distant from Tokyo and other major urban centers, such as in Chiran (Fukuma 2019), speak of the complex relationship between local and national war memories; Yasukuni Shrine and local Gokoku shrines (Shirakawa 2015) have been official and unofficial mouth-pieces for the state to glorify the war dead, and alternatively, spaces for counter-narratives (Takenaka 2015); memorials in Okinawa are intertwined with local activism while shaped by wider national and transnational forces (Figal 2018); and the memorials of Hiroshima help make it a center of local, national, and global war memory (Zwigenberg 2014). Studies of war graves in the Asia-Pacific (see papers by Alison Starr, Beatrice Trefalt, and Collin Rusneac in this special issue) have revealed that war memorials beyond Japan’s national boundaries are also important sites of Japanese and international war memory.

Through analyzing the memory politics of Kannon statues, Ishikawa, and Ryōzen Kannon from the 1930s to the late 1950s, and into recent years, this study broadens research on memorials as sites of war memory in four ways. Firstly, it reveals the role of Buddhism in the modern Japanese memorialization of the war dead, which is often considered exclusively Shintoistic, both before and after the war. Adding further complexity, it focuses on a site that was consciously founded as a Buddhist alternative to Shinto shrines such as Yasukuni. Secondly, it adds to work on the “multi-directionality” (Rothberg 2009) or “entanglements” of war memory (Zwigenberg 2014), that is, how later wars and conflicts shape the memory and memorialization materialities and practices of sites connected with the past and vice-versa. The paper does this by examining transwar continuities and connections at Ryōzen Kannon from the Asia-Pacific War, through the Occupation, and into the Cold War. Thirdly, it highlights the transnational character of war memorials—or perhaps more specifically here, bilateral ones between Japan and the US—and the influence of geopolitics on war memory (Ashplant, Dawson, and Roper 2000). In this, it builds on work into the memorialization of both Japanese and non-Japanese war dead (see papers in this special issue by Starr and Rusneac). Lastly, it explores how memorials can contribute to the active forgetting of the war dead and of past wars and conflicts (Figal 2018).

Ishikawa Hirosuke before Ryōzen Kannon

Born in Akita Prefecture in 1891, Ishikawa Hirosuke was a successful entrepreneur who skillfully adapted his business and ideological leanings to transwar politics. Starting in 1934 with Teisan Gold Mining Industries in Shizuoka Prefecture, Ishikawa established a diverse range of companies under the Teikokusan or Teisan umbrella. Literally meaning “imperial made,” this name is emblematic of Ishikawa’s attempts to tie his businesses to imperial or national causes.

In 1940, Ishikawa procured materials from the US and Canada for a bronze statue of the politically influential eighth century Japanese official, Wake no Kiyomaro (733–799) (Saaler 2020). The statue was planned by the Great Japan Association to Protect the Imperial Line (Dai-Nihon Go’ō-kai), an organization of influential political, military, intellectual, and business leaders run from a Teisan office in Ginza, who commissioned Satō Seizō (1888–1963) to sculpture it (Ōru Teisan 1974; Saaler 2020, 211). Kiyomaro was celebrated at the time for having risked his life to preserve the imperial line against being usurped by the Buddhist monk and influential political figure Dōkyō. The statue was positioned to “protect” the Tokyo Imperial Palace along with a horseback statue of another figure of fealty to the emperor, Kusunoki Masashige (1294–1336). At the height of the war, ceremonies celebrating Kiyomaro’s loyalty and self-sacrifice were held at the statue (Asahi Shimbun 19 October 1944, “Wake no Kiyomarokō no dōzōsai”). Teisan materials state that the statue had an important educational purpose (Ōru Teisan 1974). Despite the requisitioning of most bronze statues for the war effort (Saaler 2020, chapter 7), the statue of Kiyomaro still stands outside the Imperial Palace today, making Ishikawa one of few whose public monuments built during and after the war still exist. As will be explored later, its survival demonstrates the postwar endurance of the ideology of self-sacrifice for the emperor and nation, and transwar continuity in Ishikawa’s construction of public monuments.

Ishikawa was able to transition well to the economic and political transformations following Japan’s defeat. During the Occupation, Ishikawa started a car repair business in Tokyo, which morphed into Teisan Auto Co. Ltd. This company primarily repaired cars of the Occupation force (Ōru Teisan 1974). Relationships built here led to Teisan Auto providing school, work, and other bus and car services to Occupation personnel and families in Tokyo and other regions between 1946 and 1951 (Moreton 2018).

Ishikawa started several transportation companies for domestic customers, including one of the first postwar tourist bus lines (Chūbuginkō 1989). These buses eventually helped ferry hundreds of attendees to Ryōzen Kannon’s ceremonies. Teisan diversified into a wide range of other industries domestically, such as banking, driving schools, real estate, and farming. Demonstrating Teisan’s continued connection to the US and its international ambitions, under the directorship of Ishikawa’s son the company also set up a Japanese restaurant and an insurance company in Denver, Colorado in the 1970s (Ōru Teisan 1974). While most of the company’s ventures folded in the 1980s and 1990s, many of the taxi and bus companies established by Ishikawa continue as independent businesses today.

Connections with Buddhism and Kiyomaro

While Ishikawa built Ryōzen Kannon in the postwar period, the practices, ideologies, and material structures it assimilated, and Ishikawa’s monument-building ambitions that it embodied, show that in many ways it was a continuation of prewar developments. Indicating that Ishikawa carefully researched about an appropriate location, it took two years (1951 to 1953) for a site to be chosen. It then took another two years to be built before being opened on 9 June 1955. The location selected was a flat area on the edge of Kyoto’s eastern mountain range adjacent to the seventeenth century Buddhist temple Kōdai-ji (see figure 2). Among other things, this district is famous for the Buddhist Kiyomizu Temple. Known primarily today as one of Japan’s most popular tourist destinations, Kiyomizu is a renowned stop on the ancient Saigoku Kannon route connecting 33 temples in the region in which statues of Kannon are the main objects of worship. Ishikawa, it can be assumed, sought to make Ryōzen Kannon a modern addition to this pre-modern network of Kannon Buddhist temples.

Figure 2: Ryōzen Kannon and surroundings on 29 September 1956 (Yomiuri Shashinkan). The statue is in the middle, surrounded by buildings of Kōdai-ji on the left and Gokoku Shrine directly behind.

Ishikawa wished to integrate Ryōzen Kannon not only into ancient but also into contemporary beliefs in Kannon that had emerged during the Asia-Pacific War. As Kimishima has explored (2019), in the 1930s and 1940s Kannon initially became tied to the protection of soldiers, and subsequently to the memorialization of one’s own and enemy war dead as part of Buddhist onshin-byōdō rituals. In the 1930s, the potter Shibayama Seifū made and gave away many miniature “bullet-dodging Kannon” (tama-yoke Kannon) statues to soldiers and military leaders, including Matsui Iwane, the commander of the Japanese army forces that invaded China in 1937 and then committed the infamous Nanjing Massacre. In 1940, Matsui commissioned Shibayama to use clay from the battlefields of these campaigns to create a three-meter statue of Kannon in Shizuoka Prefecture that he named Kōa Kannon (Kannon for the advancement of Asia) to memorialize both Japanese and Chinese war dead (Yamada 2009).2 This statue inspired the wartime creation of other Kōa Kannon across Japan, which contributed to efforts to justify the war in China through ideas of pan-Asian affinity and Sino-Japanese friendship (Kimishima 2019; Lee 2012).

Ryōzen Kannon was also influenced by the giant forty-meter-tall Takasaki Kannon built by a construction magnate in 1936 in Gunma Prefecture to memorialize a visit by the emperor and deceased soldiers from the Takasaki army base (Kimishima 2019). Though large statues of Kannon and other bodhisattva had been built in the pre-modern period, the use of modern construction techniques and materials to construct statues that were many times larger than earlier ones, often to the extent of becoming geographical landmarks, heralded a new age in statue building.

After the war, Kannon statues were built across Japan. Following wartime models, these were initially built to commemorate war dead, as with Ryōzen Kannon and Kamakura’s Ōfuna Kannon temple and the smaller Kannon statue in Chiran for tokkō (“kamikaze”) (Fukuma 2019; Kimishima 2019). Later, they tended to be framed as symbols of peace and prosperity. These became increasingly taller, even reaching over 100 meters in the 1990s. As one of the first to be built after the war, Ishikawa’s Kannon statue is an important and influential link between wartime and postwar Kannon statue building and beliefs.

In addition to connections to Buddhism through the modern ideology and architectures of Kannon, Ryōzen Kannon physically assimilated pre-existing Buddhist sites of war memorialization. From 1908, a Chūkon-dō Buddhist pagoda for consoling the “loyal souls” of Kyoto war dead beginning with the Russo-Japanese War (1904–5) stood on the periphery of Ryōzen Kannon’s grounds (Tachibana 2011). Until the Kyoto Shōkonsha became the neighboring Gokoku Shrine in 1939 (more on this below), the Chūkon-dō was Kyoto’s only public memorial for local war dead. It existed alongside Ryōzen Kannon before being relocated to the grounds of a temple in the west of the city in 2010 (Kyoto City 2014). Given its vicinity and overlapping function as a site of memorialization, visitors to the Chūkon-dō were likely to have also visited Ryōzen Kannon. Secondly, the Reihaiden Hall containing mortuary tablets for the dead of the Japanese Empire was built on the foundations of an unfinished Buddhist ossuary constructed by soldiers of the Kyoto-based 16th Division of the Imperial Japanese Army (Tachibana 2011). Even before it was built, therefore, Ryōzen Kannon’s location was the center for local Buddhist memorials dedicated to soldiers, enabling it to inherit memorializing functions and ideologies, and likely visitors, from these earlier sites.

There are also significant links between Ryōzen Kannon and Ishikawa’s 1940 statue of Kiyomaro that suggest that not only Kyoto’s Buddhist sites but its history as the seat of Japan’s imperial dynasty, too, was central to Ishikawa’s choice of location. Elevated on a mountainside, the Kannon statue is positioned—like the Kiyomaro statue in Tokyo—as if to protect the former imperial capital. The statue can therefore be read as an extension into the postwar of Ishikawa’s wartime ambitions to construct major public monuments lionizing national self-sacrifice and symbolically guarding the emperor and the imperial dynasty. Connections to the wartime statues of Wake no Kiyomaro, Kōa Kannon, and Takasaki Kannon, and to pre-existing sites of memorialization, therefore, illustrate that surrender did not halt wartime ideology and memorialization practices in Japan but prompted them to evolve to the changing political climate.

Intertwining with Shinto: Gokoku Shrines and Yasukuni

Ishikawa actively sought to integrate Ryōzen Kannon not only with the beliefs and architectures of Buddhist memorialization and Kiyomaro worship, but also with prefectural and national Shinto war memorials. Ishikawa and, after his death, leaders of the RKK attempted to sustain, augment, and at times appropriate Shinto rituals, practices, and ideologies of memorialization of the war dead that had become dominant across Japan through Yasukuni Shrine and the Gokoku Shrines, which were prefectural “branches” of Yasukuni.

Less than fifty meters behind Ryōzen Kannon stands Kyoto Gokoku Shrine (figure 2), perhaps the prefecture’s most important modern site of memorialization of the war dead. Gokoku Shrine is the site of the former Kyoto Shōkonsha, which was built to enshrine those buried nearby who died fighting for the imperial loyalists against the forces of the Tokugawa shogunate, mostly in the 1868–69 Boshin War (Takenaka 2015). In 1869, soon after the capital was relocated from Kyoto to Tokyo, a Tokyo Shōkonsha was built based on the Kyoto version, and this later evolved into Yasukuni Shrine. Eventually, Yasukuni came to house not only the spirits of those who died in the civil wars leading to the Meiji Restoration, but also all Japanese soldiers who died in Japan’s successive modern wars, and it has been a potent symbol of soldiers’ self-sacrifice for the emperor and nation ever since. The shōkon ritual, which transforms individual war dead into Yasukuni’s collective deity, is central to this enshrinement process. In the 1930s, Kyoto Shōkonsha was transformed into Kyoto Gokoku Shrine and took its current form as a Shinto site enshrining soldiers from Kyoto Prefecture (Shirakawa 2015).

The Allied Occupation of Japan considered banning Yasukuni and the Gokoku shrines as central pillars of State Shinto and wartime militarism but, assessing that they had an important religious role, decided against this. Allied forces did, however, detach them from the state; as Mark Mullins explains, they “were essentially on probation and their future survival remained uncertain until the last year of the Occupation” (2017, 236). As the shōkon ritual necessitated written records of the multitude of dead—most of whom had not been repatriated—and a time lag after death, by the end of the war Yasukuni had enshrined only about 10% of the military war dead (Takenaka 2015). Further, it was not until the mid to late 1950s—after the end of the Occupation and the construction of Ryōzen Kannon—that Yasukuni Shrine started to again enshrine soldiers in large numbers. This offered a window of opportunity for those like Ishikawa who could offer similar services to the war bereaved.

Official publications by Teisan companies demonstrate that Yasukuni Shrine’s predicament inspired Ishikawa to build a memorial to the war dead but in a Buddhist form. An official Teisan book published after Ishikawa’s death quotes Ishikawa as having said, “Partly because of the Occupation forces’ order to withdraw state support from Yasukuni Shrine, I wished for the sorrow and pain of war victims to be wrapped in the great mercy of Kannon” (Ōru Teisan 1974, 141). Another publication quotes a senior company member saying that Ishikawa built Ryōzen Kannon because he “felt sorry” for the war dead memorialized at Yasukuni who “no one visited following separation from the state.” Furthermore, it states that Ishikawa consciously built a Buddhist site, rather than a Shinto shrine like “Yasukuni Shrine or Gokoku Shrine,” in order to avoid “American opposition and interference” (Chūbuginkō 1989, 236). Ishikawa, this indicates, envisioned his Buddhist Ryōzen Kannon to be a more acceptable version of the controversial Yasukuni Shrine. It is unclear whether Ishikawa wanted to inspire renewed militarism by building another Yasukuni. More likely, he wished to sustain the ideology of which Yasukuni and the Gokoku shrines were central institutions: revering soldiers for having sacrificed themselves for their nation.

The language and rituals of Ryōzen Kannon have similarities and differences from those of Yasukuni. A sutra book published by Ryōzen Kannon in the early 1960s (Ryōzen Kannon 1962) for bereaved families visiting the Kannon refers to the war as the “Daitōa Sensō” (Greater East Asia War), a term used by nationalists to frame the Asia-Pacific War as a battle to free Asia from Western imperialism. Ihai application forms from approximately the late 1960s (RKK n.d.), however, use “Shōwa no Taisen” (Great War of Shōwa), a term with a less nationalistic nuance that RKK perhaps judged would be more effective in engaging new customers. Both sources refer to deceased soldiers as “eirei” (heroic war dead) (RKK n.d.; Ryōzen Kannon 1962), a term primarily used to reference those enshrined as part of the collective deity at Yasukuni Shrine. While Ryōzen Kannon does not seem to have had an analogous ceremony to the shōkon ritual, Ryōzen’s collation of names and information about each person memorialized—an essential step also in shōkon rituals—along with collective ceremonies and housing of the ihai tablets in a religious institution, is clearly analogous with the collective enshrinement of Yasukuni and Gokoku shrines. Like Yasukuni Shrine (Takenaka 2015), therefore, Ryōzen Kannon’s rituals presented the death of soldiers in the context of a heroic struggle on the behalf of Asia; and, furthermore, it collectivized them, glorifying soldiers equally regardless of their wartime deeds, thereby absolving individuals of wrongdoing. This is symbolized in the “daijihi kanzeon,” the “Kannon of great mercy/compassion” that Ryōzen Kannon’s statue manifests (Ryōzen Kannon 1962).

Ryōzen Kannon did not simply substitute modern Shinto memorialization with Buddhist equivalents, but also drew on beliefs in Kannon developed during the Second Sino-Japanese War. Reflecting this, Ishikawa did not promote Ryōzen Kannon as a Yasukuni in Buddhist clothing. In a newspaper interview one month after its opening, Ishikawa described his motivation to build Ryōzen Kannon in terms of the tragic death of a fellow antique collector in an airplane accident (Yomiuri Shimbun 6 July 1955, “Hotoke to no kaikō,” 8). According to this story, Ishikawa had considered whether to buy one of two rare historical pieces: an eighth century statue of Kannon and the war helmet (kabuto) of Prince Ōtōnomiya (Moriyoshi Shinnō) (1308–1335), a contemporary of Kusunoki Masashige who, like Kusunoki and Kiyomaro, had become a symbol of fealty and sacrifice for the emperor.3 Just weeks before the accident, Ishikawa had chosen the statue while this man had purchased the helmet. For Ishikawa, this coincidence was an “encounter with Buddha” (hotoke no kaikō) that prompted him to follow “Buddha’s guidance” (hotoke no michibiki) to build Ryōzen Kannon.4 While Ishikawa may have been genuine about his new-found faith, the foregrounding and dramatization of this story here can also be read as an attempt to persuade the war bereaved that Ryōzen Kannon was not a business venture or a simple tourist attraction, but intended as a legitimate Buddhist memorial based in faith. Furthermore, the choice of Kannon over the war helmet of a martyr implies an important transformation within Ishikawa, from a man of war to one of peace.

After Ishikawa’s death in 1965, the RKK published ihai tablet application forms that were even critical of Shinto memorialization of the war dead: “For those accustomed to Buddhist memorial services passed down through the generations (sosen denrai) […] there is something unsatisfactory (mono taranai [tarinai]) about the rituals of enshrinement (hōshi) and memorialization (irei) of heroic war dead (eirei) at Tokyo’s Yasukuni and regional Gokoku shrines” (RKK n.d.). Framing the history of Buddhist rituals for the war dead as long and ancestral, and thereby those of Shinto as shallow, inauthentic, and “unsatisfying,” the RKK sought to undermine the authority of the Yasukuni and Gokoku shrines and thus convince the bereaved families of the need to use Ryōzen Kannon’s memorial services. This may have simply been a new strategy developed by the RKK after Ishikawa’s death, but the founder’s proclaimed faith in Buddhism and other factors indicate that it was an extension of earlier tendencies rather than a complete transformation of the site’s relationship with Shinto. For example, the location of Ryōzen Kannon, which physically blocks and obscures the main hall of Kyoto’s Gokoku Shrine (figure 2), can be read as an effort to eclipse the shrine and its Shinto memorialization practices.

While Ryōzen Kannon drew on the practices, ideologies, and materialities of the Gokoku and Yasukuni shrines, these links—along with those to wartime Kannon and other Buddhist memorials—do not appear to have been explicitly conveyed to the bereaved or the wider public in published materials. On-site signage does not, at least today, reference connections to Yasukuni or the neighboring Gokoku Shrine either. Silence here again points to underlying tensions at Ryōzen Kannon between endorsing and undermining the modern Shinto institutions of memorialization. Ishikawa and the RKK, therefore, sought to appropriate the collective memorialization, veneration, and—to a certain extent—enshrinement functions of the Yasukuni and Gokoku shrines while utilizing Buddhist styles of symbolism, architecture, and ritual that they likely had faith in but also out of pragmaticism. Ishikawa and the RKK were wary of US criticism, as well as alienating domestic and international visitors concerned about connections with militarism and the glorification of Japan’s war dead with which Yasukuni in particular is associated. On the other hand, they understood that dovetailing with established Shinto forms of war memorialization could also help them attract more Japanese visitors.

Ryōzen Kannon’s “International” Memorials

Stone to the Unknown Soldier and the Memorial Hall

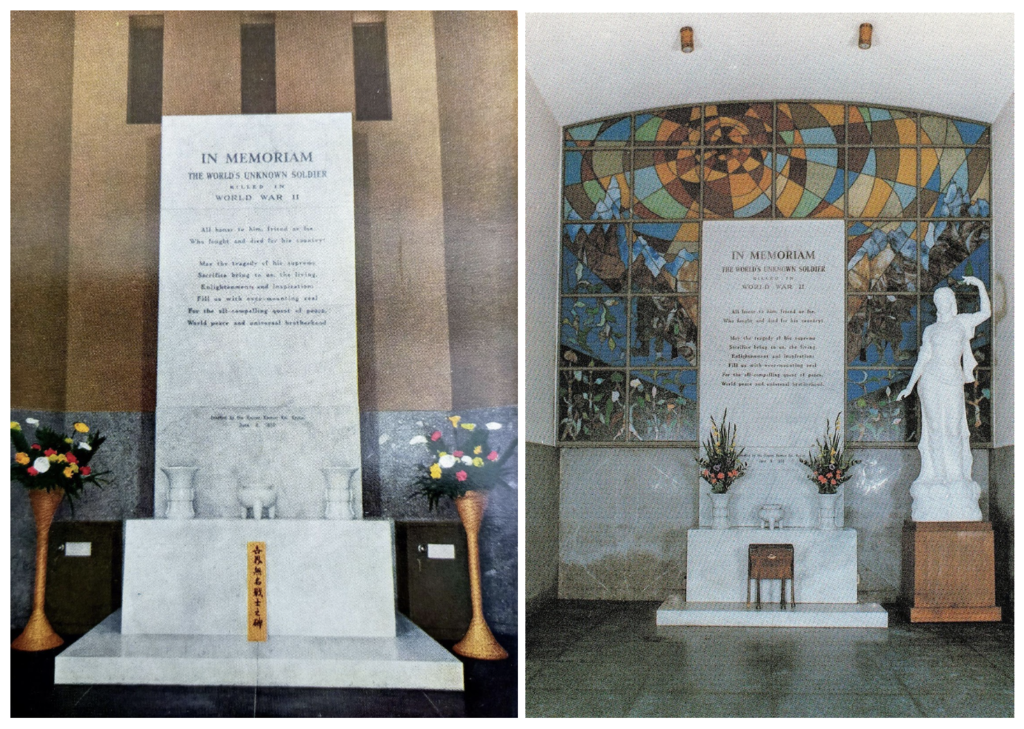

In the late 1950s, Ishikawa added a major new set of commemorative memorials and materials that significantly shifted the memory of the Asia-Pacific War presented at Ryōzen Kannon. Framed as memorials to world peace, these can be better understood as products of Cold War geopolitics and the merging of ideologies from the wartime and the US-Japan alliance. On 8 June 1958, three years after Ryōzen Kannon’s opening, Ishikawa and members of the RKK unveiled a stone monument dedicated to “the world’s unknown soldier” (figures 3 and 4). It carried the following engraving:

IN MEMORIAM

THE WORLD’S UNKNOWN SOLDIER

KILLED IN

WORLD WAR II

All honour to him, friend or foe,

Who fought and died for his country!

May the tragedy of his supreme

Sacrifice bring to us, the living,

Enlightenment and Inspiration,

Fill us with ever-mounting zeal

For the all-compelling quest of peace,

World peace and universal brotherhood.

The inscription suggests that it is a monument to all unknown soldiers of the Second World War regardless of nationality, but it was actually built to memorialize Allied POWs who died in Japanese imprisonment. This is clear in reports from the unveiling, including an American newspaper that quotes Ishikawa as saying, “the inscription on the marble dedicates the monument to ‘the world’s unknown soldier’ because the names of all those who died as Japanese prisoners cannot be inscribed on the slab” (Racine Sunday Bulletin [Wisconsin] 8 June 1958, 18). Presenting it as a memorial to all dead soldiers would likely also have helped Ishikawa justify its construction to Japanese war bereaved. The stone monument was initially located in a room attached to the main hall, beneath the statue of Kannon (figure 3), but in 1959 a separate building named the Memorial Hall was built to house it (Kyoto Shimbun 11 November 1959, 11). The Memorial Hall is a church-like, light-filled space with its name written in English across the entrance (figure 5), and large stained-glass windows depicting such scenes as flying doves and the sun over soldiers kneeling in prayer (figures 4 and 6). Today, a Western-style female sculpture (signed “Amenomiya K,” it is likely the work of sculptor Amenomiya Keiko (1931–2019)), a photo of visiting veterans from Hawai’i, and other commemorative and memorial objects surround the 2.5-meter-high stone tablet.

Figure 3 (left): The memorial tablet in its original location in a room under the Kannon statue (postcard likely from 1958–9. David Moreton collection).

Figure 4 (right): The memorial tablet soon after its relocation to the Memorial Hall (postcard likely from 1959–1960. David Moreton collection).

Figure 5 (left): Memorial Hall entrance (photo by David Moreton, 2017).

Figure 6 (right): Stained-glass window in the annex to the Memorial Hall (photo by Daniel Milne, 2020).

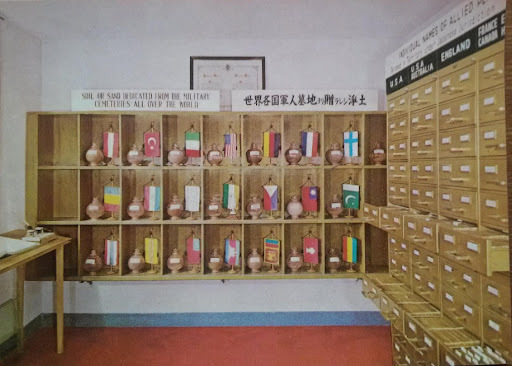

There is a small annex attached to the north side of the Memorial Hall with a collection of objects that help illustrate the meaning of the stone memorial. Along the back wall of the annex, vessels of earth from 24 war cemeteries across the world sit in a display cabinet accompanied with national flags (figures 7 and 8).5 Apart from Hawai’i, each vessel is labelled by country, both in English and Japanese. According to the flags and labels, these are (in alphabetical order): Australia, Austria, Belgium, Burma, Cambodia, Canada, Ceylon (Sri Lanka), China (referring to the Republic of China, i.e. Taiwan), Ethiopia, Finland, Germany, Hawai’i, India, Iran, Israel, Italy, Laos (Kingdom of Laos), Netherlands, Pakistan, Philippines, Thailand, Turkey, USA (Arlington), and (South) Vietnam. The Belgian soil was received from the government in 1959 and the Hawaiian from a visiting veteran group in 1962 (Moreton 2018), while comparison with a photo estimated as being from the early 1960s (figure 7) indicates that the Australian and Canadian urns were also added later. As will be discussed, only soil from the “Western Bloc” of Cold War era nations or neutral nations, including two centrally positioned urns from the USA, make up this display. Communist nations—the “Eastern Bloc”—are entirely absent, while (South) Vietnam and Laos are represented as Western Bloc nations long beyond their transformation to Communist states in 1975.

Figure 7: Memorial Hall annex with vessels of soil and cabinets holding POW cards (undated postcard, approximately from the 1960s. David Moreton collection).

Figure 8: Memorial Hall annex today (photo by David Moreton, 2019).

Along the wall to the right of the vessels are large filing cabinets containing cards with information on 48,146 POWs who died or went missing under Japanese custody during the Second World War (figures 7 and 8). These provide information identifying and explaining the fate of each individual, and are divided into countries with—according to contemporary news reports (Asahi Shimbun [evening edition] 5 June 1958)—the corresponding number of people: Australia (7,630), Belgium (1), Britain (18,117), Canada (282), China (204), Denmark (1), France (152), Holland (8,558), India and Pakistan (1,619), Italy (6), New Zealand (14), Norway (7), and the United States (11,555). The information on these cards was based on a register requested by the United Nations and compiled by the POW Information Bureau of the Japanese Army, which is now stored, but not openly accessible, at the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (Asahi Shimbun [evening edition] 31 July 2010).

Two Intertwined Memorials

The Memorial Hall is not typical of memorials (or tombs) of the unknown soldier, which first emerged in Britain and France following the First World War (see Mahon Murphy’s contribution to this special issue). Unlike most other examples, no remains nor records of unknown soldiers are held here. Instead, it was built to complement records of identified POWs. Furthermore, as Ishikawa intended it to specifically honor enemy POWs from multiple nations, it does not fit the standard pattern of such memorials as symbols of all soldiers of a specific nation and their sacrifice for that nation (Hettling and Schölz 2019). POWs and their brutal treatment by the Japanese military is a central part of war memory in Australia, Britain, and—though to a lesser extent—the USA (Frost, Vickers, and Schumacher 2019). Ishikawa’s memorial is remarkable in recognizing and providing access to rare records on them in Japan. However, the memorial’s focus on POWs indicate that Ishikawa repurposed the transcultural discourses, architectures, and memorializing practices of tombs to the unknown soldier in order to pay tribute to Teisan’s postwar patron (the company was resurrected through servicing the Allied Occupation force) and, as we explore below, honor former enemies that had become Japan’s Cold War allies. In other words, despite the engraving that indicates otherwise, Ishikawa did not intend the Memorial Hall to be a symbol of the sacrifice of all soldiers for their nation, or even of universal peace, but a homage to these specific POWs, and through them, to the Cold War alliance between Japan and the US.

The relocation of the stone to the unknown soldier from beneath the Kannon statue created a memorial space clearly marked as Western in architecture, language, and contents, which was separated from the main building and Reihaiden Hall built for those who died for the Japanese empire. Ishikawa decided to create separate memorial spaces, it would seem, in order to maintain the unity of the eirei, and perhaps thus sustain the function of the older buildings as a substitute for Yasukuni. Dividing the Allied POW and Imperial Japanese memorial spaces also helped avoid possible confrontations or criticism, including of the Japanese military by visitors familiar with their infamous treatment of POWs. Though spatially divided, however, the memorials complement each other as monuments to a reconciled past and allied present. This echoes the function and symbolism of wartime Kōa Kannon statues, such as that built by Matsui explained earlier, which through memorializing enemy and own war dead under Kannon sought to celebrate Sino-Japanese “amity” and thus obscured ongoing war and violence. Further, the size difference between the statue-capped memorial for the Japanese war dead and the Memorial Hall symbolically portrayed Japan as holding a superior—not subordinate—position relative to the USA in its Cold War alliance. Likewise, a shining sun that features prominently both in the stained-glass window behind the stone memorial for the unknown soldier (figure 4) and in the main window of the annex (figure 6) can be read as signifying Japan’s virtue and its pivotal role in promoting the peace and reconciliation represented by the Memorial Hall.

Conspicuous Absences – China and Korea

The creation of two separate memorials to the war dead created a fissure into which Japan’s Asian neighbors were concealed or vanished completely. Firstly, the display of soil conflates the Asia-Pacific War with the Cold War, making it unclear who Japan’s victims were and who bore responsibility for the earlier war. Without acknowledgment of violent or aggressive acts, the stone memorial frees everyone—primarily Japan, but also the US—from wartime responsibility. Additionally, without further information about casualties or context, the stone memorial and POW records turn a war that engulfed the Asia-Pacific into one primarily where the Japanese empire fought against the US and its Western allies. Soil from some Asian countries implies their involvement but leaves questions of whether they were enemies, allies, or were “liberated” from Western imperialism by Japan during the Asia-Pacific War, up to the visitor. Further, the absence of certain countries and the Cold-War division of others facilitates obfuscation and forgetting.

The first example of such amnesia is China. The Memorial Hall’s vessel of soil is not from mainland China but from Taiwan (the Republic of China, ROC), while its POW records include only three Chinese dead and 201 missing. Apart from underreporting (war dead in China during the Asia-Pacific War are estimated at 14 to 20 million (Mitter 2013)), one reason for this incredibly low number is that these records only cover the period from the US declaration of war at the end of 1941 to Japan’s surrender in 1945—something also stated in the stone monument. The POW records, while significant for the US and its Anglophone allies, decenter the vast majority of war casualties: soldiers who died in battle and civilians from China and other theatres of war in Asia and the Pacific islands. Set adjacent to Ryōzen Kannon’s main halls, the records of around 50,000 POWs seem equivalent to the two million Japanese and others memorialized next door, many of whom died in conflict with China both before and after 1941.

Korea is entirely absent from the Memorial Hall. For Korea, as well as China, this cannot simply be excused as stemming from a lack of diplomatic relations with Japan at the time (formal relations between Japan and South Korea were established in 1965), as urns from Hawai’i, Australia, and Canada were added in the 1960s and—for the latter two—perhaps even later. That Korea was considered a wartime “ally” (in fact, it was a part of the Japanese Empire) does not explain its absence either, as soil from countries such as Thailand, Burma, and—as discussed above—Taiwan are displayed. Rather, Koreans were excluded from the Memorial Hall as Ishikawa and the RKK saw Korea through post-annexation eyes: as indivisible from the Japanese Empire, as “Japanese” nationals at their time of death and thus not needing to be reconciled with. This is congruent with the position of Yasukuni (Barclay 2021). Indicating that Ishikawa and the RKK needed to affirm their dedication to this vision, a flurry of Korea-related services were conducted around the time of the opening of the Memorial Hall. Firstly, a Korean executed for war crimes, likely Hong Sa-ik (1889–1946), former lieutenant general in the Imperial Japanese Army, was memorialized in the main hall in 1957, and secondly a ceremony was held for executed war criminals from North and South Korea and Taiwan in 1960 (Tachibana 2011).6 Thus, despite its “international” exterior, the Memorial Hall concealed resistance to Japanese rule in Korea (1910–1945), excluded the Second Sino-Japanese War, including the Nanjing Massacre and other incidents that could put the valor of Japanese soldiers into question, and overlooked the vast majority of casualties from the Asia-Pacific War. In addition, it disregarded the Korean War, as well as the Vietnam War and the successes of Communism in the region, obfuscating entanglements with prewar Japanese imperialism and the Cold War Japan-US alliance.

Combined Ideologies – Entangled and Erased Memories

The selective “internationalization” of Ryōzen Kannon represented by the Memorial Hall was a combination of ideologies from the Asia-Pacific and Cold wars. Firstly, according to imperialist and wartime dogma, Japan’s annexation of Korea (1910), takeover of Manchuria (1931), full-fledged war with China (1937–45), and occupation of other parts of Asia as well as the war against the Allies (1941–45), were part of a mission to free the region from Western imperialism (Saaler 2007). Japan’s former enemies, therefore, were not Asian but Allied soldiers, especially Americans. The presentation of the war as a battle between Japan and the US was also encouraged by the United Nations, which focused on the 1941–1945 Pacific War period when instructing Japan to compile the POW register that Ryōzen Kannon’s cards are based on.

Secondly, the Memorial Hall demonstrated support by Ishikawa and the RKK for the concept of Japan as the leader of a “free” Asia under a US-centered world order. Specifically, the symbolic reconciliation and alliance with the Western Bloc and neutral nations represented by the urns and POW register endorsed the Cold War vision set forth by the US, and reframed and enacted by the governments of Yoshida Shigeru (1946–1947 and 1948–1954) and Kishi Nobusuke (1957–1960), while spurning those efforts made to reconcile with the USSR, such as by Hatoyama Ichirō’s government (1954–1956). In this vision, Japan is under the military protection of the US but, at least ostensibly, is equal with it. The inclusion of soil from US-aligned and neutral countries in South and Southeast Asia is reminiscent of Kishi’s Asia strategy of the late 1950s, which, mirroring his wartime ideologies of Japan as the commander of Asia, sought to establish Japan as the regional leader of a global US order (Mimura 2011). Kishi and other figures in Japan’s wartime leadership welcomed the Cold War alliance with the US as it averted attention from the Asia-Pacific War, including issues of reparations and atrocities in Asia (Igarashi 2000), and believed it was vital to reviving Japan’s economy and trade. Further, such postwar Japanese nationalists embraced the US alliance because they believed America had saved the emperor during the Occupation and had understood the imperial institution’s significance to the Japanese nation (Shirai 2018).7

Such Cold War geopolitics reveal the ideological background to Ishikawa’s transwar monuments. While his construction of the Memorial Hall may at first seem to indicate that Ishikawa turned away from nationalist monuments such as the Kiyomaro statue, it is probable that—like many leaders from his generation—Ishikawa’s patriotism simply adjusted focus from faith in Japan’s imperial mission in Asia to belief in the US alliance and Japan’s regional role. A further possible reason behind Ishikawa’s support of the alliance was that, as the head of a business conglomerate, Ishikawa had an interest in the maintenance of the very liberal-capitalist world order promoted and reaffirmed by the postwar US-Japan alliance. As explained earlier, even Ishikawa’s immediate postwar business successes were thanks to the US-led Occupation.

The Memorial Hall was not only a reflection of Cold War geopolitics. As an attractive site for US soldiers, which embodied Japan’s postwar commitment to reconciliation, it played its own part in publicizing the alliance with the US. The hall’s opening ceremony, which attracted fifty foreign diplomatic representatives and was covered in American military newspapers, was planned to gain the attention of an international audience, including US military personnel (Stars and Stripes 22 May 1958, 7). American soldiers stationed in Japan and the region were central to the revival of tourism in Kyoto (Milne 2019) and seem to have been common early visitors to Ryōzen Kannon, especially after the opening of the Memorial Hall. This is demonstrated in a 1961–1962 edition of a US Navy Cruise book, which features photos of Ryōzen Kannon along with Kinkakuji—the Golden Pavilion, perhaps Kyoto’s most recognizable tourist icon—with the caption: “Two of Kyoto’s truly beautiful sights are Kinkakuji, and the statue of Kannon, the Goddess of Mercy” (“US Navy Cruise Books” 1961–1962, 202). The Hawaiian-based Club 100, an association of Japanese-American veterans from the 100th Infantry Battalion, visited Ryōzen Kannon on their tour of Japan in 1962 (Moreton 2018). Newspaper and guidebooks often used photos of the Kannon statue to symbolize Japan’s peaceful relations with the US or provided practical information for potential visitors. An edition of the Times-Advocate, a Californian newspaper, explained that “Among the many shrines there is the Ryōzen Kannon Memorial … Mortuary Rolls and sands from each country are enshrined” (5 August 1961, 12). In 1963, another American newspaper featured a photograph of Ryōzen Kannon with the caption, “Ryōzen Kannon Memorial to Unknown Soldier of World War II in Kyoto, Japan” next to an article glowingly describing the relationship between the US and Japan (Daily Press 3 February 1963, 65).

Decline in Popularity of Ryōzen Kannon

The forty-year commemoration of the founding of Teisan in 1974—nine years after Ishikawa’s death—seems to have been a turning point for Ryōzen Kannon. Commemorative events held there drew employees from throughout Teisan’s many companies. According to the Memorial Hall’s visitor guestbook, approximately 225 people visited the hall every month during the anniversary year. However, it also shows that the number of visitors decreased across the 1970s, and people stopped signing the book in the early 1980s. Indicating declining interest among foreign tourists, the first edition of Lonely Planet’s popular series of guidebooks to Japan describes Ryōzen Kannon’s statue as, “of no historic importance, but [is]… peaceful and reassuring” (McQueen 1982, 322), while it disappears completely from the third and later editions. Visitor numbers to Ryōzen Kannon, both foreign and Japanese, have remained low in the last ten years that the authors have been visiting. What brought about the decline in popularity of Ryōzen Kannon, and what does this say about it as a site of war memory?

One cause of Ryōzen Kannon’s decline has been generational. The temple’s raison d’être, the commemoration of Japanese war dead, helped fund the temple in the 1950s and 1960s through memorial tablets and services. Close friends and direct relatives of Japanese war dead are decreasing each year, and few members of the “transitional” second and subsequent generations (Hirsch 2012) visit and memorialize war dead. Approximately 20,000 bereaved relatives from across Japan reportedly visited Ryōzen Kannon when it opened on 9 June 1955 (Kyoto Shimbun 9 June 1955, “Hanatsu higan no hato”). In contrast, recent yearly fall services are attended by fewer than fifty people (Tachibana 2011). Fewer visitors have resulted in less income, forcing administrators to make some drastic decisions, including selling or developing land into car parks.

A further reason for its decline is that, as a war memorial, Ryōzen Kannon has been left behind by the times. It increasingly lost touch with left-wing and mainstream sections of Japanese society around 1960, when mass protests against the revised US-Japan Security Treaty brought down the Kishi government. For many people, the US-Japan alliance was further tainted by American nuclear arms testing, the Vietnam War, and the occupation of and military bases on Okinawa. Additionally, the postwar generation’s desire to put the war behind them and enjoy peace (Igarashi 2000) also reduced the domestic appeal of Ryōzen Kannon and its glorification of the war dead. After the Cold War, the Memorial Hall—especially its collection of urns—would have been irrelevant or anachronistic to many contemporary visitors. Ryōzen Kannon’s memorial halls have changed little from the late 1950s, with scant effort or funds to repair, update, or add to the memorials in order to fit current politics, tourism trends, or discourses of peace. While the language on its website and on-site signage shows effort to cater to Chinese and Korean visitors, these changes are essentially cosmetic. The fundamental ideological overhaul required to appeal to such visitors, such as a list of Chinese victims of the Asia-Pacific War, seems unlikely. It would take a bold director and skillful planning to add such a memorial without negating pre-existing ones or upsetting visiting bereaved. Ishikawa, who transformed Ryōzen Kannon into a memorial to the Cold War alliance, has not been succeeded by people with his financial and social capital, nor his drive as an agent of war memory.

Changes over recent decades have actually obscured, rather than reoriented or maintained, Ryōzen Kannon’s foundations as a war memorial. Most current paid services, such as the enshrinement of ashes, mizuko kuyō services for deceased children, meditation, and shichi-go-san festive visits, are typical of temples in Kyoto. Many of these, such as mizuko kuyō, which became widespread in Buddhist temples from the late 1970s (Harrison 1998), were likely added over recent decades. Today, street-side signage (figure 10)—and to a great extent also the official website—promotes Ryōzen Kannon in Japanese and English as having the “Number one giant buddha in Kyoto” and “Guardian deity of love,” but mentions nothing of either the enshrined war dead or the Memorial Hall. This suggests that its promoters see the statue’s size, luck, and love as having wider appeal, and thus a greater chance of attracting visitors and revenue than memories of war and messages of peace. While responding to tourism demand is fundamental to the framing of perhaps all war-related sites (Elliott and Milne 2019), and is likely to have inspired the construction of the Memorial Hall, this promotional strategy turns away from the very motivation for establishing Ryōzen Kannon in the first place, transforming it into little more than a generic Buddhist temple with a massive statue. Is this a case of erasure, an effort to forget the war?

Figure 10: Street signage for Ryōzen Kannon at the road to Gokoku Shrine on Higashiōji street (photo by Daniel Milne, 2020).

Akiko Hashimoto has argued that the problem of war memory in contemporary Japan, “is not about national amnesia but about a stalemate in a fierce, multivocal struggle over national legacy and the meaning of being Japanese” (2015, 9). Over the last several decades, Ryōzen Kannon has been caught up in this deadlock between competing perspectives of Japan’s past; a fork in the road marked by the memorial’s conservative, nationalistic foundations and outdated Cold War “internationalist” addition. The Memorial Hall’s veneration of the alliance with America, which appealed to the patriotism of some during the early Cold War, is today dated and too conspicuously pro-American for contemporary nationalists and their goals of “ending the long defeat” (Hashimoto 2015, 126). On the other hand, Ryōzen Kannon does not offer a simple narrative for school group “peace-education” tourism and its visions of Japan as a wartime victim and/or aggressor (Yamaguchi 2012) as its halls are redolent of Yasukuni and its romanticization of death in war, and beautify the US-Japan military alliance. Rather than pivot to a prevalent narrative of Japan’s wartime past as hero, victim, or perpetrator (Hashimoto 2015), Ryōzen Kannon has eschewed the tricky waters of postwar Japanese memory politics. In contrast to places of active war memorialization such as Okinawa, therefore, Ryōzen Kannon has been “[de-]activated” as a site of war memory, a memorial through which the living “liberated” themselves from actively remembering past wars, conflicts, and the war dead (Figal 2018, 144) in the 1950s and 1960s, and thus a site implicated in their forgetting.

Conclusion

This paper focused on the history of Kyoto’s Ryōzen Kannon, a major yet often overlooked war memorial built by the business entrepreneur Ishikawa Hirosuke. The paper expanded on important work by Tachibana (2011), Kimishima (2019), and others to reveal Ryōzen Kannon as a complex site of entangled war memory entrenched in local and national practices and materialities of war memorialization, and shaped by the geopolitics of the Allied Occupation and the Cold War. Much like his statue of Kiyomaro, Ryōzen Kannon was a symbol of Ishikawa’s patriotism, though one that glorified Japanese war dead and venerated the postwar US-Japan alliance together with the emperor. Ishikawa adapted skillfully to the political realities of the 1950s, both to the watchful eye of the Occupation and to the opportunities that the problematic position of Yasukuni presented. The geographical, ideological, and mnemonic links between Ryōzen Kannon and the Yasukuni and Gokoku shrines shaped his decision to choose this site. While drawing on these linkages and memorial practices, however, Ishikawa and the RKK severed Ryōzen Kannon from these sites by subsuming pre-existing Buddhist memorial structures and ideologies and framing it as a peaceful Buddhist alternative that equaled Yasukuni’s collective veneration of soldiers but surpassed it in its claims to historical and cultural authenticity.

The paper significantly deepened work begun by Tachibana (2011) and Moreton (2018) into the transnationalism of Ryōzen Kannon. Though seemingly a site of world peace, the Memorial Hall was an extension of wartime ideology into the geopolitical realities of the Cold War. Through the stone tablet, materials on POWs, and the urns of cemetery soil, Ishikawa implicitly defined the enemy to be reconciled with as America and maintained the wartime ideology of Japan as the benefactor of Asia. It thus became an agent for what Yoshikuni Igarashi (2000) has explained as the repression of memories of Japan’s violence against other countries—especially China and Korea, as well as of the violence of Cold War brinkmanship. Further, by becoming a notable attraction for American soldiers, it conveyed Japan’s commitment to the US alliance and a view of Japan as a rightful and trustworthy regional leader. It thus contributed to the role of tourism in postwar US-Japan relations (Milne 2019).

Lastly, the paper contributes to understanding shifts in ways of commemorating, remembering, and dis-remembering the Asia-Pacific War in Japan (Aukema 2019; Elliott and Milne 2019; Figal 2018) by tracing the rise and decline in popularity of Ryōzen Kannon, and how it has become a site for the forgetting of past wars and the war dead. It was concluded that this decline was a consequence of its leadership’s unwillingness to engage in the torrid struggle over remembering the war by reinvigorating Ryōzen Kannon as a site of contemporary war memory, and to instead frame it as a regular Buddhist temple and tourist attraction. Rather than being a space to reflect over the violence and destruction of the Asia-Pacific War, therefore, it has become a place to leave such issues in the past. As the history of this and other war-related memorials teach us, however, there is always the possibility that Ryōzen Kannon will once again transform itself. It may even endeavor to fulfill the pledge carved into stone at its Memorial Hall to be filled “with ever-mounting zeal” for “world peace and universal brotherhood” and become a site that recognizes Japan’s past wrongs and war responsibilities and condemns the violence of current and past international conflicts.

References

Ashplant, T. G., Dawson, Graham, and Roper, Michael. 2000. “The Politics of War Memory and Commemoration: Contexts, Structures, and Dynamics”. In T.G. Ashplant, Graham Dawson, Michael Roper (eds.) The Politics of War Memory and Commemoration. London: Routledge, 3–86.

Aukema, Justin. 2019. “Cultures of (Dis)remembrance and the Effects of Discourse at the Hiyoshidai Tunnels.” Japan Review 32: 127–150.

Barclay, Paul D. 2021. “Imperial Japan’s Forever War, 1895–1945.” Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus Vol. 19, Issue 18, No 4: 1-30.

Chūbuginkō. 1989. Chūbuginkō-shi. Tokyo: Toppan Publishing.

Elliott, Andrew, and Milne, Daniel (eds.). 2019. War, Tourism, and Modern Japan, special issue of Japan Review 33.

Figal, Gerald. 2018. “The Treachery of Memorials: Beyond War Remembrance in Contemporary Okinawa.” In Patrick Finney (ed.) Remembering the Second World War. London: Routledge, 143–157.

Frost, Mark R., Vickers, Edward, and Schumacher, Daniel. 2019. “Introduction: Locating Asia’s Memory Boom.” In Mark R. Frost, Daniel Schumacher, and Edward Vickers (eds.) Remembering Asia’s World War Two. London: Routledge, 1–24.

Fukuma Yoshiaki. 2019. “The Construction of Tokkō Memorial Sites in Chiran and the Politics of ‘Risk-Free’ Memories.” Japan Review 33: 247–270.

Harrison, Elizabeth G. 1998. “‘I can only move my feet towards mizuko kuyō’ Memorial Services for Dead Children in Japan.” In Damien Keown (ed.) Buddhism and Abortion. London: Palgrave, 93–120.

Hashimoto, Akiko. 2015. The Long Defeat: Cultural Trauma, Memory, and Identity in Japan. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hettling, Manfred and Schölz, Tino. 2019. Translated by Nicholas Potter. “Bereavement and Mourning.” In Ute Daniel and Peter Gatrell et al. (eds.) 1914–1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War. Berlin: Berlin Freie Universität.

Hirsch, Marianne. 2012. The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture After the Holocaust. New York: Columbia University Press.

Igarashi, Yoshikuni. 2000. Bodies of Memory: Narratives of War in Postwar Japanese Culture, 1945–1970. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Kimishima Ayako. 2019. “Heiwa kinen shinkō ni okeru kannonzō no kenkyū.” Doctoral thesis. The Graduate University for Advanced Studies, Hayama, Japan.

Kyoto City. 2014. Shinshitei, tōroku bunkazai. [Accessed 17 April 2021].

Lee, Seyun. 2012. “Onshin-byodo in the Sino-Japanese War and the Russo-Japanese War” (Japanese). Interdisciplinary Studies of Japanese Buddhism 10: 69–87.

McQueen, Ian. 1982. Japan: A Travel Survival Kit. Melbourne: Lonely Planet.

Milne, Daniel. 2019. “From Decoy to Cultural Mediator: Changing Uses of Tourism in Allied Troop Education about Japan, 1945–1949.” Japan Review 33: 143–172.

Mimura, Janis. 2011. “Japan’s New Order and Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere: Planning for Empire.” Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus Vol 9, Issue 49 No 3.

Mitter, Rana. 2013. China’s War with Japan, 1937–1945: The Struggle for Survival. London: Allen Lane.

Moreton, David. 2018. “Ryōzen Kannon: A Temple Built for World Peace.” POW Kenkyūkai Kaihō 20: 28–35.

Mullins, Mark R. 2017. “Religion in Occupied Japan: The Impact of SCAP’s Policies on Shino.” In Emily Anderson (ed.) Belief and Practice in Imperial Japan and Colonial Korea. Singapore: Palgrave, 229–248.

Ōru Teisan yonjyūnenshi henshu iinkai (ed.). 1974. Ōru Teisan yonjyūnenshi. Tokyo.

RKK (Ryōzen Kannon Kai). No date. “Ihai: Ryōzen Kannon ni omatsuri suru ihaikuyō ni tsuite.” Leaflet produced by Ryōzen Kannon.

Rothberg, Michael. 2019. Multidirectional Memory: Remembering the Holocaust in the Age of Decolonization. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Ryōzen Kannon. 1962. Ryōzen Kannon sanbutsu kashū. Kyoto: Ryōzen Kannon.

Saaler, Sven. 2006. Politics, Memory and Public Opinion: The History Textbook Controversy and Japanese Society. 2nd ed. Munich: Iudicium.

Saaler, Sven. 2007. “Pan-Asianism in Modern Japanese History: Overcoming the Nation, Creating a Region, Forging an Empire.” In Sven Saaler and J. Victor Koschmann (eds.) Pan-Asianism in Modern Japanese History. Oxon: Routledge, 1–18.

Saaler, Sven. 2020. Men in Metal: A Topography of Public Bronze Statuary in Modern Japan. Leiden: Brill.

Seaton, Philip A. 2007. Japan’s Contested War Memories: The “Memory Rifts” in Historical Consciousness of World War II. London: Routledge.

Shirai Satoshi. 2018. Kokutairon: Kiku to seijyōki. Tokyo: Shūeisha.

Shirakawa Tetsuo. 2015. “Senbotsusha irei” to kindai Nihon: Jun’nansha to Gokoku Jinja no seiritsu shi. Tokyo: Bensei Shuppan.

Tachibana Naohiko. 2011. “Kyōto chūreitō to Ryōzen Kannon.” Bulletin of the Folklore Society of Kyoto 28: 149–171.

Takenaka, Akiko. 2015. Yasukuni Shrine: History, Memory, and Japan’s Unending Postwar. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

“US Navy Cruise Books.” 1961–1962 edition. Fold 3. [Accessed 30 December 2020].

Yamada Yūji. 2009. “Matsui Iwane to Kōa Kannon.” The Journal of History and Archaeology, Mie University 9: 8–21.

Yamaguchi Makoto. 2012. “Hiroshima shūgaku ryokō ni miru sensō taiken no henyō.” In Fukuma Yoshiaki, Yamaguchi Makoto, and Yoshimura Kazuma (eds.) Fukusū no “Hiroshima.” Tokyo: Seikyūsha, 256–310.

Zwigenberg, Ran. 2014. Hiroshima: The Origins of Global Memory Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Notes

Interestingly, this is the same year that the Chidorigafuchi National Cemetery, which was also planned as a Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, was established in Tokyo.

Matsui’s statue reemerged as a site of conflicting war memory after the war. The ashes of Matsui and six other Class A war criminals sentenced to death at the Tokyo Trials were reportedly taken to the temple overseeing the statue in 1949 and interred in a memorial for “The Seven Warriors” (shichi-shi no hi) in 1959. In 1971, an extremist group blew up the new monument and unsuccessfully attempted to do likewise to Matsui’s statue (Kimishima 2019; Saaler 2006).

The person directly involved in this acquisition largely recounted this story after Ishikawa’s death (Chūbuginkō 1989, 235) but with less drama and no mention of Ishikawa’s religious enlightenment.

The cabinets were built by the Japanese office furniture company Kurogane in about 1959 (Moreton 2018, 33).

Whether individual Taiwanese were also memorialized, whether families and communities were consulted and other issues merit further study. On related issues at Yasukuni, see Takenaka (2015).

Thanks to Justin Aukema for this insight. Aukema’s article in this special issue further explores the transformation of postwar ideology in Japan through concepts of modernization in veterans’ interpretations of their wartime experiences.