Abstract: This article examines Filipino memories of the Asia-Pacific War. In particular, it investigates which survivor accounts developed into the dominant historical narrative as well as looks at how prisoner of war monuments on Camp O’Donnell have been influenced by political and economic developments after the Asia-Pacific War. This study also re-examines how these shared memories about Camp O’Donnell complemented each other and became part of the canonical wartime narrative in Philippine history. This article uses “politics of mourning” as a framework in analyzing key events that led to both the development of canonical narratives in the construction of public history as embodied in the monuments and shrines in the present-day Capas National Shrine.

Keywords: prisoners of war, the Philippines, Camp O’Donnell, Capas National Shrine, politics of mourning, shared memories, public history

Introduction

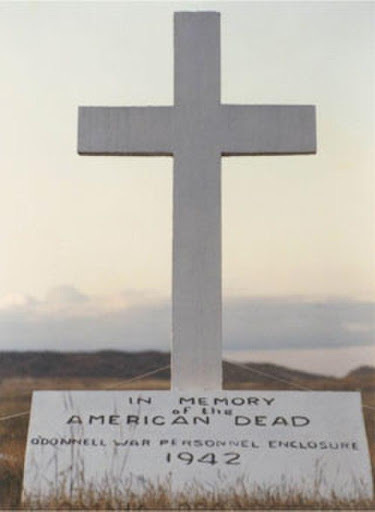

On 9 April 1942, in the face of overwhelming disadvantage caused by hunger and disease, Major Gen. Edward P. King, Jr. was forced to surrender the tens of thousands of USAFFE soldiers defending the Bataan Peninsula to the besieging Imperial Japanese Army. The Bataan Death March followed shortly as most of the Filipino and American prisoners of war (POWs) were forced to walk under tortuous conditions about 100 kilometers from Bataan to San Fernando Pampanga, and boarded tight box cars towards Capas, Tarlac. Around 10,000 American soldiers and an estimated 50,000 Filipino servicemen ended up in Capas, Tarlac in Central Luzon. Camp O’Donnell, a hastily converted Philippine Army training camp, saw the death of about 1,600 Americans and some 26,000 Filipinos. Camp O’Donnell was infamous in the Philippines during its short-lived existence as a USAFFE POW camp synonymous for suffering and death. By mid-1942, the surviving American POWs were gradually transferred to other POW camps, while the Filipinos were granted conditional pardons by the Japanese. A cement cross memorializing the American war dead was erected at the behest of the Japanese in an attempt to reach out to the American POWs. On 20 January 1943, however, Camp O’Donnell was closed by the Japanese. By the time that the Americans liberated the Philippines in 1944 and 1945, all that was left in the by-then desolate field was the cement cross.

Figure 1: “Map of the Philippines showing the location of Bataan.”

(Wikimedia Commons. Map created by Eugene Alvin Villar, 2003.)

Figure 2: “Route taken during the Bataan Death March.

Section from San Fernando to Capas was by rail.

(Wikimedia Commons. Map created by Howard the Duck, 2008.)

This article argues that in the evolution of historical memory of Camp O’Donnell, survivor accounts, consisting of shared memories, promoted a canonical narrative in the Philippines’ collective history of the Asia-Pacific War. At the same time, the development of a public history in the form of POW monuments was influenced by political and economic developments during and after the war. Survivor accounts left behind by former POWs and civilians during and after the war developed a common narrative from shared experiences in Camp O’Donnell.

These wartime narratives were necessary to prove that war crimes were in fact committed by the Japanese. During the Manila War Crimes Trial in 1946, these shared memories of the atrocities at Camp O’Donnell were used as evidence to indict Lt. Gen. Honma Masaharu of the Imperial Japanese Army for war crimes. Though individual memories are recalled in hundreds of memoirs, the actual site of Camp O’Donnell has almost disappeared. In most of the published survivor narratives, Camp O’Donnell usually comes third in the wartime narrative beginning with the three-month-long siege of Bataan from January to early April 1942, followed by the Death March. It is only in Col. John E. Olson’s O’Donnell: Andersonville of the Pacific (1985) that a detailed narration and study specific to Camp O’Donnell has been published. Olson’s “crusade” focused on the retrieval of the original cemented cross monument that lay abandoned in the former POW camp. The monument was successfully brought to the United States in early 1991. Later in 1991, the Capas National Shrine, a secular memorial, was created by the Philippine government, honoring the Filipino-American POWs who died there.

Framework of Analysis: Canonical History as Public History

The analysis and discussion for this article revolves around shared memories that lead to the development of public histories. However, that process of development is influenced by political and economic forces. In the case of the history of Camp O’Donnell, shared memories are collectively represented by the multitude of survivor accounts. These are classified in this study as (a) insiders, or from the point-of-view of the POWs themselves, and (b) outsiders, or from the reference point of the multitude of civilians directly involved. Individual accounts of wartime survivors have, over the past few decades, been produced and when compared, do corroborate and support each other. These created a shared memory of individual yet common experience.

This study also posits that this shared memory serves as the basis of public history, in the form of monuments and museums. Ludmilla Jordanova states that public history is “seen or read by large numbers of people and has mostly been designed for a mass audience” (2006, 126). Jordanova goes on to caution that public histories are influenced by politics and business given that the construction of museums and/or monuments are sanctioned by the state and possibly financed by private groups (2006, 137). Public history thus embodies certain “interest” and may be “sponsored by businesses” (2006, 137). In the case of Camp O’Donnell, public history refers to the complex of monuments and museums contained in the present-day Capas National Shrine. Its construction was ordered by the Philippine government in 1991 and it was partly financed by veterans’ groups and other organizations. However, this study goes further into addressing the very motivations that led from shared memories to the construction of public history.

The political motivations leading to the 1991 establishment of Capas National Shrine may be explained by the concept “Politics of Mourning.” This concept was outlined by Nakano Satoshi and Hayase Shinzō who wrote extensively on war memorials in relation to the historiography of the Japanese occupation of the Philippines. Nakano points out that the Philippines became the first foreign country to host an official, large-scale overseas Japanese Pacific War monument. In December 1973, President Ferdinand E. Marcos ratified the Philippine-Japan Treaty of Friendship, Commerce, and Navigation (Nakano 2003, 338). Earlier that year, on 28 March, the “Memorial for the War Dead” was inaugurated in Caliraya, Laguna (Hayase 2010, 158). Although there has been no Japanese war monument built in Capas since the end of the war, the frenzy of World War II monument construction by American, Filipino, and Japanese groups started during the Martial Law years. On 7 December 1991, Marcos’ successor, President Corazon C. Aquino, through Proclamation No. 842, transformed Camp O’Donnell into a much grander Filipino monument now encompassing present-day Capas National Shrine (Campo 2021).

Whereas the American memorial in present-day Capas is a replica, the entire shrine complex itself was a product of the Philippine government’s peace overture to the United States at the height of a growing anti-American sentiment in the Philippines during that period. The POW monuments at the Capas National Shrine were constructed in light of political and economic developments in the late 1980s and early 1990s. To explore this idea further, this study borrows from Nakano Satoshi’s framework, “Politics of Mourning,” in order to understand the various interests or agenda for which recollections were published or monuments erected (Nakano 2003, 337-376).

This study builds on Nakano and Hayase’s arguments in situating the role that reminiscences enshrined in both published accounts and public monuments play in constructing canonical memories. For Camp O’Donnell, the dominant narrative based on American and Filipino survivor accounts has been uncritically accepted as a standard story of unspeakable inhumanity and suffering brought on by Japanese brutality. At the same time, individual accounts catalogue a taxonomy of suffering for the tens of thousands of American and Filipino POWs.

Both Nakano and Hayase posit that the meanings created and evoked by monuments are politically motivated and economically driven to favor the parties that sponsored their construction. Nakano, in his “Politics of Mourning”, discusses the political and economic motivations behind the sudden construction boom for Japanese war memorials that started in the Philippines in 1973. He highlights the pressures and opinions ranging from those of Japanese families to those of the Filipinos. The latter initially displayed lukewarm support for what seemed to be an enshrinement of the perpetrators of atrocities during the wartime period. Hayase Shinzō (2010, 145-150) echoes these sentiments in addition to his narration of personal observations and experiences while visiting the Japanese war memorials in the Philippines.

Survey of POW Accounts

Many American POW accounts about their experiences at Camp O’Donnell have been published, including one from 1944. However, only a few have been produced by Filipino survivors. Nevertheless, American and Filipino POW accounts corroborate each other in regard to the common narratives of Japanese atrocities, disease, and deprivation that led to deaths of tens of thousands of POWs in 1942. In the American accounts, the common denominator is that these accounts are meant to eternalize the memory of their collective suffering as POWs. A corollary to this is the intent to justifiably indict those responsible for the war crimes inflicted on the POWs. The very few existing published Filipino POW accounts equally recall the memories of hardships, albeit from the Filipino side of the camp. The larger number of Filipino accounts, however, were written by civilians who had relatives then incarcerated in Camp O’Donnell.

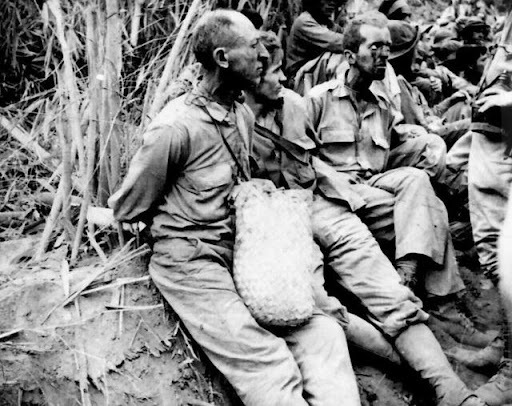

Figure 3: “Photograph of Prisoners Along the Bataan Death March.”

(US National Archives (NARA), 532548.

Department of Defense, Department of the Navy.

General Photograph File of the U.S. Marine Corps, 1927-1981.)

The earliest known account in the United States that details the horrors of the Bataan Death March and Camp O’Donnell is that of Lt. William E. Dyess, Bataan Death March: A Survivor’s Account (1944). Dyess, a US Army Air Force officer was in Camp O’Donnell before being transferred to another POW camp in Davao, Mindanao, from where he managed to successfully escape. Although Dyess was repatriated to the US, he died in late 1943 in a plane crash. His book became the very first account from which the Americans learned of the wartime atrocities committed by the Japanese on POWs in the Philippines (Legarda 2016, 82).

In the aftermath of the American Liberation of the Philippines in 1945 came the depositions of various American former POWs. The Allied Translator and Interpreter Section (ATIS) compiled these collections of sworn statements for use in the war crimes prosecution of the Japanese military leadership. From January to April 1946, two Japanese officers were indicted for war crimes in relation to the inhumane treatment and conditions in O’Donnell POW camp: Lt. Gen. Masaharu Homma and Capt. Yoshio Tsuneyoshi. The latter was the POW camp commandant assigned from the opening of the camp to the POWs, until mid-1942. The ATIS depositions are valuable for historians. The documents detail individual POW experiences of suffering and death in Camp O’Donnell, replete with handwritten notes and diagrams of the camp, among other materials.

Numerous POW accounts were also published in the immediate postwar period. In the existing literature of published POW books, the second first-hand account written by a former Camp O’Donnell inmate was that of Col. Ernest B. Miller, Bataan Uncensored (1949). It must be noted, however, that these POW accounts recount Camp O’Donnell as part of a series that begins with Bataan and ends with the American POWs being transferred from Camp O’Donnell to other POW camps in the Philippines or in Japan. Other accounts end with the American POWs successfully escaping a prison camp and joining or organizing a guerrilla outfit.

Although there are only a few published Filipino POW accounts, these narratives do corroborate and share the trauma of suffering and deprivation suffered by the Americans in their side of Camp O’Donnell. In particular, Lt. Col. Fidel L. Ongpauco’s They Refused to Die: True Stories About World War II Heroes in the Philippines, 1941–1945 (1986, 146–235) contains detailed narratives and descriptions of life in Camp O’Donnell from the Filipino POWs’ point-of-view. Ongpauco had the materials and the opportunity to draw his observations of camp life. The author managed to successfully preserve his original diagrams and sketches, and later published in 1986 as part of his wartime memoir. Ongpauco’s illustrations are significant in the historiography of the POW camp because the available photographs widely circulated in 1942 were taken by the Japanese for propaganda purposes. Although Japanese photographs show the cheerless American and Filipino POWs in Camp O’Donnell, they do not show the inhumanity suffered inside the camp. For this, Ongpauco’s crude illustrations provide a more comprehensive visual companion to the dark vivid narratives detailed by both American and Filipino accounts. For example, in one sketch, Ongpauco depicted a specific Filipino POW, Pvt. Rico Adriano, as having lost his sight due to Vitamin B deficiency. In other sketches, he memorialized other POWs by illustrating their pitiful physical conditions in the camp. Ongpauco’s artistic accounts provide a Filipino expression of the narrative of suffering and hardship at Camp O’Donnell.

From Individual Experiences to Shared Memory: POW Accounts

By bringing together the multitude of individual POW accounts, we can get a firmer grasp on the shared memory and dominant narratives of POW camps. For Camp O’Donnell, the American accounts detail the daily suffering and deprivation that the tens of thousands of POWs endured. Distilled from existing POW accounts, the following are the common elements in the narrative. The Filipino POWs were somewhere between 40,000 to 50,000, while the American POW population was around 10,000. The two lived in separate sections of the camp. US Army officers of general and full colonel ranks lived separately from the other American POWs. The POWs started arriving in batches into Camp O’Donnell on 11 April 1942. All accounts recall the “welcome speech” by the camp commandant.

You are cowards and should have committed suicide as any Japanese soldier would do when facing capture… I only regret that I cannot destroy you all, but the spirit of Bushido forbids such practice. It is only due to the generosity of the Japanese that you are alive. The slightest violation of orders will result in execution. I have already shot many Filipinos in the last week for violation of orders. You are the eternal enemies of Japan. We will fight you and fight you for one hundred years! You will pay for the way the Japanese have been treated by Americans. We will never be friends with the piggish Americans. You have no rank. You will wear no insignia, and you will salute all Japanese regardless of rank. (McManus 1965, 232–233, see also, Boyt 2004, 142; Dyess 1944, 99-100; Cross 2006, 112-113).

POWs were billeted to different huts and makeshift shanties where they were free to roam within their assigned areas in the camp. Food was rationed by the Japanese and consisted of meagre amounts of dirty rice gruel. Filipino POWs were, however, able to partly improve their diet through food brought in by an authorized relative/s. The local residents as well as the relatives of the Filipino POWs made innumerable attempts to bring in or otherwise smuggle food and medicines into the camp. The Americans’ chances for survival increased if they could afford the food and other supplies successfully smuggled and secretly sold by the Japanese into the camp (Dyess 1944, 105-106). Initially, there were only two water spigots in the entirety of the camp to supply water for the tens of thousands of POWs. Many POWs suffered from severe dehydration because of this. Afterwards, water details were organized daily to procure water from the nearby O’Donnell River.

From their campaign in Bataan and during the Death March, many of the POWs contracted malaria and/or dysentery. Combined with malnutrition, almost 1,600 Americans and about 20,000 Filipinos died in Camp O’Donnell. The daily death rate from malaria and dysentery was staggering. The only camp hospital, dubbed as the “Zero Ward,” was considered a place to die rather than a hospital (Sneddon 1999, 67). Despite the best efforts of the camp’s American and Filipino military doctors who were also POWs, they were unable to help the malaria and dysentery sufferers. Quinine for malaria and the sulfa drugs for dysentery already disappeared as early as the Bataan campaign. Instead, dysentery patients were given boiled guava leaves, but with varying results, to relieve them of symptoms.

Figure 4: “Photograph of American Prisoners Using Improvised Litters to Carry Comrades.”

(US National Archives (NARA), 535564.

Office for Emergency Management, Office of War Information.

Photographs of the Allies and Axis, 1942-1945.)

Filipino accounts, for their part, not only corroborate, but also support the American POW narratives. Both Americans and Filipinos shared individual experiences and memories of hardships inside the camp. However, unlike the grim accounts narrated by the American POWs, Filipino recollections, though recognizing the sheer inhumanity inside the camp, present an initially upbeat and optimistic view of POW camp life. Even Fidel L. Ongpauco’s account seems to be more jovial and trivial at first, presenting an initially ironic optimism in the otherwise hopeless conditions inside the camp (Ongpauco 1982, 127). However, Ongpauco’s sketch-filled account gradually descends into grimmer and somber tones as the weeks and months progressed and the death toll rose significantly. For all the POWs, Camp O’Donnell was “Camp O’Death” (Tenney 2000, 65).

American and Filipino POWs shared similar narratives of traumatic experiences. Both suffered harsh treatment from the Japanese and both shared experiences of deprivation and disease inside the camp. Yet, the main difference between the American and Filipino POWs was the latter’s access to family, relatives, and friends. The Filipino POWs’ ties and familiarity with the local community created for them a stronger sense of hope for survival. Within a few weeks inside the camp, the Filipino POWs received letters, messages, and parcels from their families and relatives. Many of their relatives managed to reach the vicinity and crowded the gates to the camp (Pestaño-Jacinto 2010, 49-50). The American POWs however had to rely on themselves and whatever they could get from the Red Cross parcels and other means to survive. By mid-1942, the Japanese gradually released all the surviving Filipino POWs. While the Filipino POWs gained their freedom by mid-1942, the American POWs were transferred to other equally harsh POW camps in the Philippines and Japan for the duration of the war.

In all the POW accounts, whether by American or Filipino survivors, narratives of hardship and deprivation are fully discussed and detailed. Condensed, these constitute the shared memory of the POW survivors. The standard canonical narrative which emerges from the existing survivor accounts details war crimes committed by the Japanese from Bataan all the way to the POW camp in 1942. This shared memory from Bataan to O’Donnell became the unspoken foundation that defined US-Philippine military defense relations in the decades following the end of the war in 1945.

Complementing Shared Memories: Civilian Accounts

Apart from POW accounts, a good number of civilian narratives also emerged after the war in the form of published memoirs and diaries, complementing the shared memory of Camp O’Donnell (Lichauco 1997, 36-39; Pestaño-Jacinto 2010, 44-51). The majority of wartime civilian accounts that mention the camp ordeal are those of relatives of Filipino POWs who happened to be incarcerated there in 1942. The significance of this genre of accounts is that it gives an alternative perspective from those of the POW or “insider” accounts. It must be taken into consideration that while the Americans were literally isolated in 1942 in a POW camp in the Philippines, thousands of kilometers away from their homeland, Filipinos were in closer proximity to their families. Although Filipino POWs hailed from various islands all over the Philippines, many were also from Manila and other parts of Luzon Island. Regardless of where the Filipino POWs were originally from, this meant that one way or another, their relatives would try to contact them no matter how difficult it seemed at that time.

Camp O’Donnell became a secular pilgrimage site akin to Catholic religious pilgrimage sites such as the Cathedral of Antipolo (Nieva 1997, 129). Instead of seeking spirituality however, Filipinos sought proof-of-life of their relatives. Filipino civilians conceived of ingenious ways and means to alleviate the hunger, thirst, and illnesses affecting the camp population. In Memoirs and Diaries of Felipe Buencamino III, 1941–1944, Lt. Felipe Buencamino III (2003, 134) narrates and describes how prominent families from Manila used their wealth and connections to save their relatives from the Death March and Camp O’Donnell. Such efforts were met with varying success. Some Filipino POWs had wealthy parents or relatives who bargained with the Japanese for their immediate release. Although it was considered shameful for them to desert their suffering compatriots, an untold number of early releases of Filipino POWs were made possible by elite families who contacted and negotiated with high-ranking Japanese officials or Filipino officials collaborating with the Japanese.

As for the less fortunate Filipino POWs, survival or release from Camp O’Donnell was made possible through various layers of negotiations with local public officials (Ongpauco 1986, 233). Filipino accounts mention hundreds of relatives flocking outside the gates of the POW camp in a futile attempt to bring in food and medicine to them. These attempts were met with varying levels of success. Anecdotes abound of people who woefully failed to contact their relatives inside the camp and ended up giving away food and supplies to any random POW inside the camp (Pestaño-Jacinto 2010, 51).

Outside the gates of the POW camp, numerous groups from Manila gathered to extend their assistance to help the POWs. “They would not rot like pigs in Capas” was the desperate cry of the Filipino POWs and their relatives (Pestaño-Jacinto 2010, 46). Civilian institutions from Manila such as the Philippine Red Cross and the Archdiocese of Manila sent trucks and representatives with supplies and physicians to try to help those in Camp O’Donnell. Prominent women such as Josefa Llanes Escoda and Lulu Reyes organized teams from Manila to try to bring in aid to Capas (Legarda 2003, 91; de Veyra 1991, 75). Unfortunately, most of the care packages sent to Camp O’Donnell by the aid agencies from Manila were never received by the POWs (de Veyra 1991, 75). According to an American POW account: “Red Cross food parcels as well as medical supplies were stashed away and never given out, delayed issue, and then gave out very small amounts at a time. Had all parcels been delivered to the POWs as intended, the extent of starvation in captivity would have been lessened appreciably” (Noell n.d., 53).

The official reason for blocking the care packages stemmed from Japanese Army propaganda which said that it was an insult to the Emperor for the Imperial Army to accept outside aid from civilians (Olson 1985, 40; Tsuneyoshi 1945). Despite these setbacks, families of the prisoners and welfare groups continued to persist in bringing medicines, canned goods, and even toiletries into the camp. The guards made them deposit the relief goods at the gate, promising that they would be delivered to the intended beneficiaries. However, accounts indicate that the Japanese took most of these for themselves and only a portion reached the POWs (Legarda 2003, 91). Through the Philippine Red Cross, many care packages were sent, some were allowed into the camp gates, and almost all were ransacked by the Japanese (Noell n.d., 55).

Even the persistence of medical volunteers was met with the brutality of the Japanese guards and their commandant at the gates of O’Donnell. One of the Red Cross physicians, Romeo Y. Atienza was badly beaten up after he failed to bow before the Japanese camp sentries (Atienza 1946). Oscar Jacinto, a surgeon and his team from Malate, Manila however, successfully gained entry into the camp by claiming that they were there to provide medicine to the ailing commandant and were eventually permitted to administer injections to POWs (Pestaño-Jacinto 2010, 42). Most of the civilians outside the camp gates persistently waited. Whenever the gates opened, civilians flocked to the POWs to give them whatever food and medicine they could provide (Ibid., 44). Americans were equally treated with generosity (Poweleit 1975, 67). Through these efforts, many of the POWs managed to survive their ordeal, despite the seemingly insurmountable odds against them.

The plight of the POWs also became part of the shared historical memory of the local population of Tarlac Province where Camp O’Donnell is located. According to accounts, the local people rendered assistance to the POWs while they were on the way to the POW camp in April 1942 by providing them food or helping them escape (Buencamino 2003, 134; Gloria 1978, 93; Ingle 1981, 12608; Olson 1985, 27–28). Accounts also point to invaluable aid provided by prominent local officials and businessmen in sending food, medicine, disinfectants, and other supplies into the camp (Castro, Salak, and Bonifacio 1953; Cojuangco 1997, 220; Olson 1985, 40; Ongpauco 1986, 157; Raventos 1981, 223–224).

With the presence of tens of thousands of POWs, Camp O’Donnell was transformed from a remote military installation to an integral part of the local community’s shared memory. Community members and public officials became active participants in the drama unfolding in their neighborhood stirred up by the tens of thousands of POWs, the Japanese, and innumerable civilians flocking the camp’s gates throughout 1942. In the shared memory of the Capas residents, Camp O’Donnell became part of the community’s local history.

Overall, the civilian accounts – the POWs’ relatives, private organizations, and the local population – do support the POWs’ canonical narratives inside Camp O’Donnell. Similar to the POW accounts, all of the civilian narratives also share in the common memory of a humanitarian crisis and indict the Japanese for what can only be understood as war crimes.

Olson’s “Crusade”: A Politics of Mourning

If survivor accounts constitute shared memory among the the former POWs, war monuments represent public histories of the Asia-Pacific War. Monument construction to honor the Camp O’Donnell POW war dead began as early as 1942. The development of a public history, however, was not devoid of political influences, even in 1942. Col. John E. Olson’s O’Donnell: Andersonville of the Pacific (1985, 236–238) specifically recounts the existence of an American monument and reprints a previously published article, “A Sack of Cement”. According to Olson’s narrative, which became the standard narrative for the monument, the Japanese themselves provided the cement and commanded the Americans to build a monument for their war dead.

On one particularly hot and miserable day in late June 1942, the Japanese supply sergeant, nicknamed “Banjo Eyes” by the American prisoners, unceremoniously gave the American supply officer a “presento” [sic] of one sack of cement. Without providing any other directions or instructions, the Japanese supply sergeant simply stated “Now, courtesy of Imperial Japanese Army, you make shrine for men who die.” (National Park Service 2017).

The result was a monument composed of a cross and a base, with a dedication “IN MEMORY OF THE AMERICAN DEAD/ O’DONNELL WAR PERSONNEL ENCLOSURE/ 1942,” and the words “OMNIA PRO PATRIA” (Ibid.). A famous 1945 photograph of Gen. Douglas MacArthur reverently standing before the American monument has been widely circulated. Apart from these references to the American monument, there is no other mention of it in war crimes records or other documents.

Figure 5: “The Camp O’Donnell WW II American POW Grave Memorial Cross (1942).

Located at the U.S. Naval Radio Station, Tarlac, Republic of the Philippines.”

(Wikimedia Commons. Photograph by Richard K, Cole, Jr, 1985.)

However, a short documentary video has been produced by filmmaker Richard Randolph “Randy” Olson summarizing the struggle that his father, John E. Olson, undertook to bring the monument to the United States (Olson, 2020). According to the video, “The Sack of Cement Cross: John Olson’s Last Military Campaign,” John E. Olson visited the site of Camp O’Donnell twenty years after the war. He was appalled that the site of Camp O’Donnell had become nothing more than a grassland marked only by the lone cross monument. In the following decades, Olson petitioned numerous American and Filipino politicians, as well as various interest groups in his bid to relocate the monument to the United States, but to no avail. The video mentions that Olson finally decided to organize a unit of Navy SEALs and succeeded in taking the monument out of the Philippines, just in time, as Mt. Pinatubo in nearby Zambales Province erupted and devastated the entire region in 1991.

Why did John E. Olson undertake a crusade to bring the monument into the United States, when he could have just left it there marking the historical site of Camp O’Donnell? Was it because it was an American monument? After all, the remains of the American dead at Camp O’Donnell were reburied after the war in a military cemetery near Manila. Nevertheless, the American POW monument represented official public memory, at least for the American veterans. Utilizing Nakano’s “Politics of Mourning,” it is necessary to understand the political conditions of the 1980s and early 1990s specific to US-Philippine Relations. By the mid-1980s, the Filipino view of the Americans was at an all-time low in the aftermath of the EDSA People Power Revolution that toppled the Marcos dictatorship in 1986. Many Filipinos viewed Marcos as an American puppet and after the peaceful revolution, there was a very strong nationalist sentiment under the Aquino administration that sought to remove American interests in the Philippines. On 16 September 1991, the Philippine Senate rejected the American bid to renew the lease for the US naval bases in Subic Bay and Clark Airfield (Shenon, 1991). There was popular anti-US sentiment as Filipino nationalist and leftist political groups condemned American presence in the Philippines as imperialistic. This served both as motivation, and ironically, the go-signal for Olson’s plan to succeed in 1991. The monument which was built by the American POWs in 1942 is now at the National Prisoners of War Museum in Andersonville, Georgia.

Olson’s crusade represents the Americans’ desire to preserve the then only existing public monument to the history of Camp O’Donnell. Given political developments in the late 1980s and early 1990s leading to the closure of the US Naval bases in the Philippines, Olson and the American war veterans decided to rescue their public history from abandonment and oblivion. However, an irony in the saga of the Olson crusade is that the same Philippine government started the revitalization of the Camp O’Donnell historical site when President Aquino created the Capas National Shrine in December 1991. In effect, the entire area, though affected by the Mt. Pinatubo eruption, was cordoned off as a historical site, which effectively protected both Filipino and American historical places of interest in the area.

From Politics of Mourning to Public History: Capas National Shrine

Whereas the American shrine became the only notable concrete structure that remained to mark the American war dead in Camp O’Donnell after 1942, there were legal precedents for the remembrance of the Filipino war dead as early as 1943. Despite possible Japanese retribution, local officials sought official public recognition for the Filipino soldiers who fought in Bataan and were buried in the vicinity of Camp O’Donnell. Under the sponsorship of Assemblyman Sergio L. Aquino, Act Number 10, “An Act declaring ‘Libingang Pambansa’ (National Cemetery) a portion of the concentration camp of Filipino POWs in barrio O’Donnell, municipality of Capas, province of Tarlac, and appropriating funds therefor. (B. No. 11)” was enacted into law by the National Assembly in 1943 (Agoncillo 2001, 949). Unfortunately, the only surviving evidence of an actual marker constructed in the Filipino area of Camp O’Donnell to identify its status as a national cemetery was constructed after the war. Nonetheless, the 1943 Law provided the legal precedent for the transformation of the area into a protected historical site.

The problem was that this law did not do much to officially memorialize Camp O’Donnell as it was completely abandoned by the Japanese until the end of the war. Immediately after the war, the United States Air Force took over the reservation, but the area remained abandoned and forgotten. In 1956, the then governor of Tarlac Province, Benigno Aquino, Jr., commissioned the construction of a Death March monument supposedly to commemorate its terminus at Capas. Many consider the monument to be a tourist marker rather than an historical monument. Worse, the monument, built in the shape of an inverted V-shape was placed in the town of Bamban along the MacArthur highway – nowhere near the actual site of Camp O’Donnell.

April 9 has always been an annual holiday, Araw ng Kagitingan or Day of Valor, commemorating the Fall of Bataan. Most, if not all, the state functions used to take place exclusively in Bataan and were well-attended by Filipino and American veterans. Until 1991, no official state-sanctioned commemoration took place in the vicinity of Camp O’Donnell. In 1978, however, things changed when the Japanese were finally allowed to participate in the annual Bataan Day commemoration activities (Hayase 2010, 162). Five years earlier, the Japanese were allowed to start building their monuments for their own war dead in the Philippines. A competition between the families of the Japanese war dead and the American veterans’ associations for monument construction thus began.

The Americans were well-organized long before the advent of Marcos-era Japanese interests. American veterans groups were organized almost immediately after the war. Two of the well-known associations are the Battling Bastards of Bataan (BBB) and the American Defenders of Bataan and Corregidor (ADBC). Both have been active in the development and maintenance of the Bataan memorial shrine and the Corregidor islands as historical sites. These veteran associations, along with their Filipino counterparts, organized under the Philippine Veterans Affairs Office (PVAO) have always been active in maintaining the memory of Bataan and the Death March through civic activities and Bataan Day memorials. Despite the vibrant veterans’ activities and projects, however, Camp O’Donnell continued to remain an abandoned grassland until the 1990s.

In the wake of the American withdrawal of its naval bases from the Philippines in 1991, there were frenzied attempts on the part of the Cory Aquino administration to maintain close relations with the United States. After all, President Aquino was saved by the US Navy from military coup attempts in 1989. In return, she strongly opposed the removal of the US naval bases. After having failed, she instead focused on salvaging whatever remaining ties the Philippines had with the United States. On 7 December 1991, President Aquino created the Capas National Shrine through Proclamation No. 842, s. 1991: Reserving for National Shrine Purposes to be known as “Capas National Shrine” a Certain Portion of Clark Air Base Military Reservation Located in the Municipality of Capas, Province of Tarlac, Island of Luzon (Aquino, 1991). Months earlier, Olson and his Navy SEALs succeeded in spiriting away the only monument in existence then in Camp O’Donnell, to the United States (Olson, 2020). Although the Mt. Pinatubo eruption diverted public attention, it was undeniably an embarrassment for the Philippine government to fail to preserve historical sites from abandonment and destruction. As such, the new Capas National Shrine was to be constructed and maintained by the Philippine government.

After years of lukewarm interest, the Philippine government finally turned its attention to the decaying state of the Camp O’Donnell site. This may be interpreted as the Cory Aquino administration’s desire to revive and rehabilitate US-Philippine Relations by reconstructing and developing Camp O’Donnell as a public history shared by both Filipinos and Americans.

Figure 6: Capas National Shrine.

(Wikimedia Commons. Photograph by Ramon F. Velasquez, 11 April 2013.)

On 9 April 2003 came the inauguration of the obelisk marking the center point of the Camp O’Donnell historical park site. According to the official online brochure, Capas National Shrine is comprised of 54 hectares of state-protected parkland, 35 of which were planted with 31,000 trees, each representing one of those who died there in 1942. The 70-meter obelisk is surrounded by black marble walls containing the engraved names of the Filipinos who died in Camp O’Donnell. A museum and a reconstructed 1942-era Camp O’Donnell also complement the historical complex. Several meters away is a replica of the American cross monument with a white marble wall behind it containing the names of the Americans who died there. The BBB commissioned the revitalized American monument as well as the “Bridge of Remembrance” over O’Donnell River. Recently, the Capas National Shrine has gradually been integrated into the New Clark City commercial zone which, optimistically, could bring in more tourists into the area. Despite the grandiose transformation in 2003, Capas National Shrine remained a remote location accessible only by private vehicles and organized tour groups. Prior to the 2020 Covid Pandemic, the Capas National Shrine had been one of the official venues for the annual 9 April Day of Valor commemoration activities. Various American and Filipino veterans’ organizations, historical associations, local governments, and civic groups regularly held annual events on site to commemorate the Fall of Bataan. Apart from these, chartered groups organized by and for American war veterans were shuttled into the shrine to hold private ceremonies and tours. Locally, various schools and universities held periodic educational trips for Philippine history students to visit the historical Camp O’Donnell site, which was otherwise only read about in textbooks.

Present-day Capas National Shrine is a public history monument representing shared memory of what was once a harrowing POW camp in 1942. Survivor accounts represented individual yet common experiences from both POWs and civilians. A shared memory developed as embodied in the existing canonical narrative. However, monuments represent public history, and unlike private memoirs, require state sanction and financial sponsorship to be constructed and maintained. Capas National Shrine was built to honor the shared memory of both Filipinos and Americans who suffered and died in Camp O’Donnell in 1942. However, Capas National Shrine would not have been constructed if not for the political conditions that developed in the international relations between the United States and the Philippines from the 1970s to the early 1990s.

Figure 7: “Omnia Pro Patria in Capas National Shrine, a cross dedicated to fallen American soldiers in Bataan during Japanese occupation.” (Wikimedia Commons. Photograph by Julan Shirwood Nueva, 6 November 2019.)

Shared Memory and Public History: Conclusions

This article has analyzed how the various participants remembered and memorialized their wartime experiences at Camp O’Donnell. Published American and Filipino POW accounts are numerous yet consistent in remembering Camp O’Donnell as a place where they suffered horrendously and witnessed tens of thousands of their compatriots die of diseases in the most miserable conditions. Civilian accounts share in the memory of hardships and deprivations presented by the corpus of POW accounts. Accounts from the perspectives of relatives, POWs, and representatives of private organizations corroborate the narratives of hardship and deprivation in the camp. Notwithstanding, the local community has been dragged into becoming active participants in what has become a collective shared experience and memory of Camp O’Donnell. Both POW narratives and civilian accounts have contributed to the shared memory that has developed into a standard canonical narrative of the Camp O’Donnell story.

Apart from the published accounts which constitute the individual and collective shared experiences of the participants in the Camp O’Donnell tragedy, shrines and monuments were built to immortalize official histories. Public history in the form of war monuments represents the goal of immortalizing the shared memory of the events of 1942. In the case of these monuments, they themselves constitute histories behind the public history, which may be explained using the framework of the politics of mourning. The very first monument, the white cross for the American war dead, was an awkward but failed attempt by the Japanese to reach out to the Americans. The fact that both Filipinos and Americans shared the same experience of struggle and hardship in Camp O’Donnell became part and parcel of the unbreakable bond between the Filipinos and the Americans in the postwar period. Despite an admittedly unequal relationship, the Camp O’Donnell experience became a common memory shared by both Filipinos and Americans. For most policymakers, the wartime struggle against a common enemy, Japan, defined the mutual interests of the United States and the Philippines.

Shared memories could have developed into lofty public histories. Unfortunately, this was not automatically the case as Camp O’Donnell did in fact become an almost lost and forgotten site of memory after 1945. Despite the abundance of references in the multitude of World War II accounts, Camp O’Donnell embodied a painful memory of defeat and dehumanization. The survivors were torn in their crusade to immortalize the past on the one hand, and their desire to heal and forget on the other. As a result, the standard historical memory regarding April 1942 almost always focused on Bataan and the Death March. The sufferings and deaths of the POWs in Camp O’Donnell appear as an after-thought, almost completely forgotten. It is no wonder that, while the Bataan memorial is well developed and maintained, Camp O’Donnell would have been left to decay, if not for the strange events and a volcanic eruption that occurred in 1991. “Politics of Mourning” reminds us that public histories in the form of official state-sanctioned monuments are not without politics and pressures. At the moment, the Capas National Shrine represents not only shared memory but also public history.

References

Agoncillo, Teodoro A. 2001. The Fateful Years: Japan’s Adventure in the Philippines, 1941–1945. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

Aquino, Corazon C. 1991. Proclamation No. 842 s. 1991. Reserving for National Shrine Purposes to be known as “Capas National Shrine” a Certain Portion of Clark Air Base Military Reservation Located in the Municipality of Capas, Province of Tarlac, Island of Luzon. [Accessed 21 February 2021].

Atienza, Romeo Y. 1946. (Sworn Statement). Allied Translator and Interpreter Section, “Trial Brief Homma Case Camp O’Donnell Case (File No. 10–1) Filipino Side” (Mimeographed), Bundle #6, Volume 75, National Archives [of the Republic of the Philippines].

Buencamino III, Felipe. 2003. Memoirs and Diaries of Felipe Buencamino III (1941–1944). Edited by Victor A. Buencamino, Jr. Makati City: Copy Cat Incorporated.

Boyt, Gene. 2004. Bataan: A Survivor’s Story. Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, Norman.

Campo, Darwin M. Capas National Shrine. [Accessed on 3 March 2021].

Capitly, Bonifacio E. 1953. “History of the Barrio of Aranguren,” “Historical Data of Tarlac” Bureau of Public Schools. Microfilm. The National Library [of the Philippines]. Roll Number 72.

Castro, Lilia S. Socorro M. Salak, and Liberata M. Bonifacio. 1953. “Historical Data for the Town of Capas,” “Historical Data of Tarlac.” Bureau of Public Schools. Microfilm. The National Library, Roll Number 72.

Cojuangco, Margarita R. 1997. Tarlac: Pre-history to World War II. Esmeralda Cunanan (ed.). Tarlac, Tarlac: The Tarlac Provincial Government, The Sangguniang Panlalawigan ng Tarlac, and The Tarlac Provincial School Board.

Cross, Russell G. 2015. In the Rays of the Rising Sun: The True Story of Private Glen E. Kuskie’s Survival As A Member of the US Army 31st Infantry Regiment During World War II. North Carolina: First Lulu.com.

De Veyra, Manuel E. 1991. Doctor in Bataan. Quezon City: New Day Publishers.

Dyess, William E. 1944. The Dyess Story: The Eyewitness Account of the Death March from Bataan and the Narrative of Experiences in Japanese Prison Camps and of Eventual Escape. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

Gloria, Claro C. 1978. All The Way From Bataan to O’Donnell. Quezon City, s.n.

Hayase, Shinzō. 2010. A Walk Through War Memories in Southeast Asia. Quezon City: New Day Publishers.

Ingle, Donald F. 1981. (Direct examination statement). Transcript of the Proceedings in Open Session, Pages 12,393–14,954, vol. 6, The Tokyo War Crimes Trial: The Complete Transcripts of the Proceedings of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East in Twenty-Two Volumes. John R. Pritchard and Sonia M. Zaide (eds.). New York and London: Garland Publishing.

Jordanova, Ludmilla. 2006. History in Practice. New York: Hodder Arnold.

Legarda, Jr., Benito P. 2003. Occupation ’42. Manila: De la Salle University Press.

Legarda, Jr., Benito P. 2016. Occupation 1942-1945. Quezon City: Vibal Foundation, Inc.

Lichauco, Marcial P. 2005. Dear Mother Putnam: A Diary of the Second World War in the Philippines. Quezon City: VJ Graphic Arts, Inc.

McManus, John C. 2019. Fire and Fortitude. New York: Penguin Random House.

McMurray, Marisse R. 1996. Tide of Time. Makati City: Jose Cojuangco and Sons.

Nakano Satoshi. 2003. “The Politics of Mourning.” In Ikehata Setsuho and Lydia N. Yu-Jose (eds.) Philippines-Japan Relations. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press.

National War Crimes Office. “People of the Philippines vs. Yoshio Tsuneyoshi,” Mimeographed. Bundle #69, Volumes I, II, and III (National Archives).

Nieva, Antonio A. 1997. The Fight for Freedom: Remembering Bataan and Corregidor. Quezon City: New Day Publishers.

Noell, Jr., Livingston P. No date. “Remember How They Starved Us!” Packet #10. Herman E. Molen and the National Medical Research Commission (eds.). USA: American Ex-POW Incorporated.

Olson, John E. 1985. O’Donnell: Andersonville of the Pacific. Lake Quivira, Kansas: Self-published.

Olson, Randy. 2020. The Sack of Cement Cross: John Olson’s Last Military Campaign. [Accessed 31 January 2021].

Ongpauco, Fidel L. 1986. They Refused to Die: True Stories About World War II Heroes in the Philippines, 1941–1945. Manila: Vera-Reyes.

Pestaño-Jacinto, Pacita. 2010. Living with the Enemy: A Diary of the Japanese Occupation. Pasig City: Anvil Publishing Incorporated.

Poweleit, Alvin C. 1975. USAFFE: The Loyal Americans and Faithful Filipinos: A Saga of Atrocities Perpetrated During the Fall of the Philippines, the Bataan Death March, and Japanese Imprisonment and Survival. Place of publication not identified: Self-published.

Shenon, Philip. 16 Sept 1991. “Philippine Senate Votes to Reject US Base Renewal.” The New York Times. [Accessed 5 March 2021].

Sneddon, Murray M. 2000. Zero Ward: A Survivor’s Nightmare. Bloomington, IN: iUniverse.

Tenney, Lester I. 2000. My Hitch in Hell: The Bataan Death March. Washington, DC: Potomac Books.

National Parks Service (USA). 2017. “The Sack of Cement Cross.” [Accessed 20 January 2021].

Tsuneyoshi, Yoshio. 1945. (Statement from cross examination). National War Crimes Office. “People of the Philippines vs. Yoshio Tsuneyoshi.” 3 vols. Mimeographed. Bundle #69, Volumes I, II, and III. National Archives.