The Japanese version of this letter follows this English translation. 日本語版が英語版の後に掲載されています。

Introductory Note by Akuzawa Mariko

This letter is more than our expression of dissent to the article, “On the invention of Identity Politics: The Buraku Outcastes in Japan” by J. Mark Ramseyer; it is meant to call for the participation of Japanese scholars in fact-checking. It is a matter of academic integrity for all scholars who are engaged in research on Buraku issues to have their voices included. We need sociologists, historians, and scholars from other disciplines to fully examine this highly problematic article. By writing this, we want to get the ball rolling.

Therefore, the letter, sent to the editors-in-chief of the Review of Law and Economics, was also published in full on the website of IMADR, an international human rights NGO. For publication in The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, we have made minor modifications by adding some endnotes.

In addition, our letter does not just address those in the academic community. The general public has no access to such an academic paper, let alone the people from Buraku communities. We believe it is the responsibility of academics to provide evidence of the author’s academic fallacies to the broader society, as part of our shared challenges against a dangerous form of historical revisionism.

A key point is that Ramseyer, writing almost two decades after the termination of the last Dōwa Special Measures Law, asserts that Burakumin identity is “fictive” and seeks to nullify it. When the law was still in effect, empowerment and “coming-out” by Buraku communities and individuals with Buraku origins were preconditions for designation as recipients of Dōwa Special Measures Projects. However, since the termination of the law, many schools stopped teaching anything that might lead to identifying Buraku (communities or personal origin) on the assumption that it was wrong to identify them without legal foundation.

At the same time, over the course of the implementation of the Dōwa Special Measures Projects, significant demographic changes took place in Buraku communities (many migrated away for educational and career options, as well as for marriage with non-Buraku partners etc.). These are some of the changes that were brought about as a result of narrowing gaps between Buraku and non-Buraku communities, both physically and psychologically.

On the other hand, these changes resulted in a diversification of identity among those with Buraku origins, and in the weakening of Burakumin identity among the younger generation who do not know nor are taught about their family backgrounds in many cases. In addition, with generational change, there are fewer elderly people who have memories of past discrimination or commitment to the liberation movement and in this situation communities become more susceptible to the attempts of historical revisionists who distort and overturn the facts and historical consensus.

Finally, in our letter, we noted the author’s unethical use of the National Survey of Buraku (1936). The data has been repeatedly abused for background checks to identify Burakumin. The data, deliberately posted on the website by an individual sometime in 2015, was ordered to be removed by a Japanese court injunction in April 2016, and the order was affirmed by the higher courts. However, RLE published Ramseyer’s article that uses this survey data in 2019. Did the editorial board have any experts on the Buraku issue review the article? Was the editorial board aware that the data source that the author used was prohibited by Japanese courts? Did the author make the editorial board aware of this? The editors of RLE carry great responsibility for the publication of the article.1

To the Editors-in-Chief of the Review of Law and Economics

Akuzawa Mariko and Saito Naoko

We are sending this letter to express our grave concern as scholars about the publication of the article by J. Mark Ramseyer, entitled “On the invention of Identity Politics: The Buraku Outcastes in Japan” in your journal (Volume 16 issue 2, 2019). Both of us are researchers and educators at the Research Center for Human Rights at Osaka City University, known as the first university in Japan that in 1970 deployed full-time faculty for research and education on Buraku discrimination. Since then, research and education on behalf of human rights have been our Center’s mission, not to mention that studies on Buraku discrimination constitute an integral part of our work.

From our perspective as researchers on Buraku discrimination for many years, the article is based on a fallacious interpretation of the history of social movements that arose within Buraku communities. Neglecting the fact that the postwar Dōwa Special Measures projects for the improvement of Buraku communities were based on national laws, he describes them as the outcome of “shakedown” strategies of the specific Buraku organization. The article then misuses statistical data to draw a conclusion that complies with the author’s preconceived ideas on Burakumin and Buraku communities. The problematic use of national census data of 1936 (Zenkoku buraku chōsa [National Survey of Buraku]) should be also noted.

We lay out some of the critical issues below. As sociologists, we center our concerns within that realm and leave numerous historical concerns to historians. The following is not an exhaustive list, however, rather the concerns we raise here are those we consider the most egregious. We believe they are significant enough for the editorial board to re-examine the article.

While our concerns with Ramseyer’s scholarship outlined here centers on Buraku issues, it is not the first time that Ramseyer has been criticized for highly problematic scholarship. An article on “comfort women” that Ramseyer published in International Review of Law and Economics has been criticized heavily by scholars across the globe from a variety of disciplines. Numerous scholars have raised questions and concerns over Ramseyer’s misrepresentation of facts, problems with methodology, citation issues, and what seems to be a willful ignoring of data that would counter his preconceived notions, and indeed, the journal has appended an “Expression of Concern” to the on-line article.

As scholars, we uphold professional standards and procedures. Ramseyer’s article on the Buraku issue does not meet even a minimum level of academic integrity. It discredits the work of social scientists who try to work in ways that inspire trust and confidence in society.

Our discussion below is divided into five sections. Sections 1-4 are written by Akuzawa Mariko, while Section 5 is written by Saito Naoko.

1. Negligence of the legal basis of Dōwa Special Measures

First, the author, neglecting the political and legal process of Dōwa Special Measures projects, misleads readers by suggesting that the projects were the outcome of a “shakedown” strategy of a specific Buraku organization. In fact, it was the Dōwa Policy Council, an advisory body of the prime minister that in 1965 recommended the policies and the legislation of the Dōwa Special Measures Law to provide a legal basis for national subsidies for policy implementation. The first law came into force in 1969. In other words, from the start, this was a policy program that had its foundation within the government.

2. Misinterpretation of demographic changes in Buraku communities

Secondly, considering the author’s apparent fluency in Japanese, the lack of engagement with recent scholarship in Japanese is nothing short of inexcusable. There are myriad examples of research that highlights demographic changes in Buraku communities, as well as examples of community changes through “first-hand accounts”, such as public data from national and local governments.

Instead, ignoring this body of research, the author links the demographic changes of Buraku communities with “criminal incentives” created by the subsidies for Dōwa Special Measures projects, and draws a far-fetched conclusion: that the national subsidies increased incentives for “burakumin with the lowest opportunity costs” to stay in the communities and “invest in criminal careers”, whereas those “with higher legitimate career options abandoned the community” (in the abstract, 1). The author also states that the end of the subsidies stopped such incentives, and “young buraku teenagers increasingly stayed in school. They finished high school, left the buraku for university, and never returned” (85).

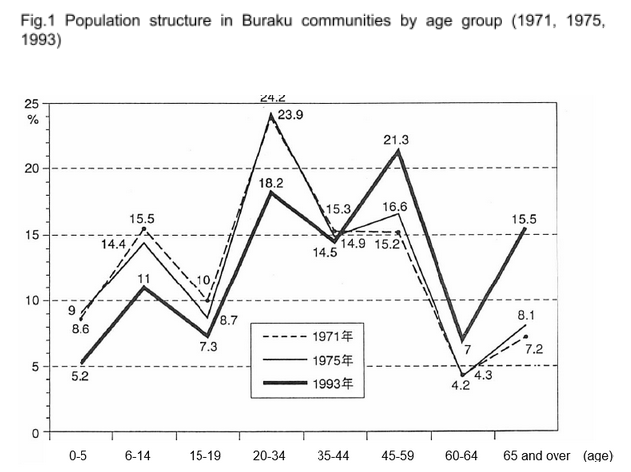

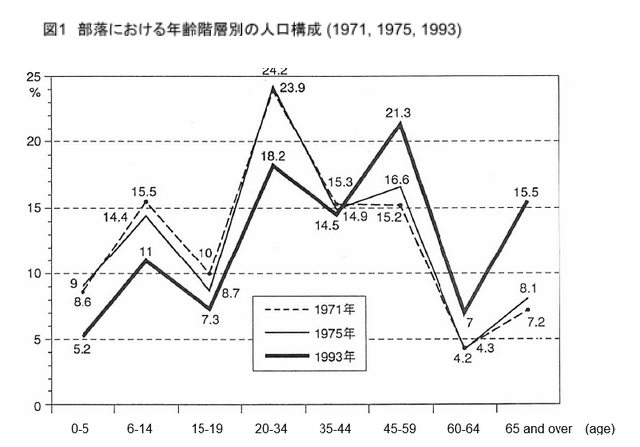

Contrary to the author’s claim, publicly available data demonstrates the following facts: Fig.1 shows the population structure in Buraku communities by age group in 1971, 1975, and 1993, showing the demographic changes of Buraku Communities under Dōwa Special Measures Laws.2 The percentage of those under fifteen years of age constituted 24.1% of total population in 1971, whereas it went down to 16.2 % in 1993. The percentage of the elderly (above 65) increased from 7.2% in 1971 to 15.5% in 1993.

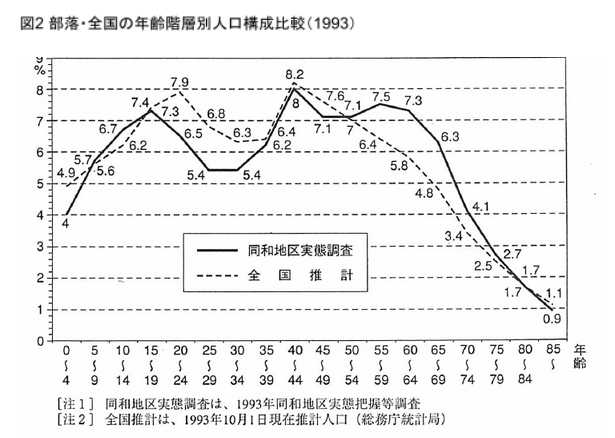

Fig.2 shows a comparison of population structure by age group between Buraku communities and the total national population in 1993. In Buraku communities, the percentage of the young generation between 20 and 34 years old was comparatively lower, while the percentage of those above 55 was higher.

Those figures imply that during the period of the Dōwa Special Measures, the younger generation left Buraku communities after finishing their education, thus leaving the remaining population disproportionately elderly compared with total national population.3 Ramseyer describes those Burakumin who stay in their communities as those who “faced ever-larger incentives to stay in the buraku and invest in criminal careers” (in the abstract, 1) and enhances violent images of Burakumin. This is pure speculation. Is Ramseyer attempting to say that the elderly who stay in Buraku communities are violent and dangerous?

Another public data source, the surveys conducted by Osaka prefecture in 1990 (大阪府同和対策業対象地域住民生活実態調査, Survey of the Living Conditions of Residents of Target Districts of the Dōwa Policy Project, Osaka Prefecture, 1990, hereafter the 1990 Survey) and in 2000 (同和問題の解決に向けた実態調査, Survey of the Conditions which Point Towards the Resolution of the Dōwa Problem, 2000, the 2000 Survey) give “first-hand accounts” of the background to the demographic changes of the forty-eight Dōwa districts (an administrative term that refers to Buraku communities) in Osaka, mostly urban communities, just before the end of Dōwa Special Measures projects.

Prior to the expiration of the Dōwa Special Measures Law in 2002, changes of policies and laws took place during the transitional period from the late 1990’s. One such example was the amendment of the Public Housing Law in 1996 which had a large impact on population movement particularly from urban Buraku communities.

The total population living in Buraku communities in Osaka prefecture had fallen from 111,435 in 1993 to 95,468 in 2000 (a decrease of 15,967). In the 2000 Survey, questionnaires were randomly distributed among 10,000 residents over 15 years of age in Buraku communities, and it found that 9.4% of the total respondents (n=7676) were “born outside of the Buraku communities where they then resided”, and had “moved into these areas within the last ten years”. If we apply that percentage to the whole population including those under fifteen, the total estimated number of those who were born outside and came into these communities within the last ten years was 8,974 (Okuda 2002).4

Building on this, Okuda estimated the number of people moving out from Buraku communities of the same period. If we ignore the natural increase and decline in population, the minimum estimated number of those who moved out was 24,941 (15,976[decrease]+8,974[those came in and replaced those who moved out]), comprising 26.1 % of the total population in 2000.

The large movement out of urban Buraku communities took place to a great extent due to the amendment of the Public Housing Law in 1996 with the end of housing rent subsidies under Dōwa Special Measures. The rent in public housing thereafter was determined by household income and the rent simply became too high for households with higher incomes to continue living in public housing. As a result, many had to leave.5 The vacancies were filled with new residents with economic difficulties (Okuda ibid.; Uchida et.al 2005).6 Applications for occupancy in public housing after 1996 were open to the general public and so a large percentage of relatively new residents who moved into Buraku communities were presumably from non-Buraku, households.

It is wrong to attribute the mobility of Buraku residents to their “criminal incentives”, since ample public data accounts for demographic changes in Buraku communities that the author completely neglected.

Some local governments have continued to gather data on the conditions of Buraku communities after the expiration of the Dōwa Special Measures law. One example is Tatsuno-city in Hyōgo prefecture, which conducted a survey in Buraku communities in 2020 whose results were released to the news media. Other prefectures, such as Osaka, Wakayama and Fukuoka have used data from the national population census (Kokusei-chōsa 国勢調査) to assess the condition of the areas formerly connected with the Dōwa Special Measures projects. There is then some data in the public domain that the author could have used.

3. Misuse of statistics

To draw a conclusion that fits the author’s preconceived bias, Ramseyer creates a highly problematic index, “Burakumin PC” (explained as the number of burakumin, divided by total population), and uses it as a crucial variable. However, is it reasonable to compare the fraction of Burakumin in 1993 and other indices that represent social phenomena at prefectural level nearly 20 years later, as the author tries to do (27)? The author finds positive correlations between the fraction of Burakumin and some variables including Crimes per capita (2010) and Methamphetamines crimes per capita (2011), Welfare dependency (2010) etc., concluding that several indices reveal dysfunctional behavior of Burakumin (27). Considering the percentage of Burakumin in the prefectural population in 1993 was between 0% and 4.289% (Table 3, 23) the article has to face the criticism that it is creating an abusive image of Buraku using data with “the risk of ecological fallacy” (22) , which is seriously high.7 The author again uses the index (Burakumin PC) later in the article (such as at 52). After finding that Burakumin PC of 1907 correlates with his “Total crimes PC” (total crimes divided by total population) and “Murders PC” (total murders divided by total population), the author stated “the higher the fraction of burakumin in a prefecture, the higher the rates both of total crimes generally and of murders specifically” (52). Again, as the author confesses, the risk of “ecological fallacy” (51) is too high, especially the numbers of Buraku and non-Buraku crimes and murders are not distinguished when calculating “Total crimes PC” and “Murders PC”.

Clearly the author recognized this was an ecological fallacy yet continued to make these unsubstantiated claims.

4. False explanation about the career paths of Buraku youth

The author explains that the Dōwa Special Measures (the national subsidy) “encouraged young burakumin men to drop out of school, stay in the buraku, and join the criminal syndicates” (77), misleading readers to think that national subsidies promoted diversion of the future paths of Buraku youth into criminal careers.

Again, it is shocking that the author neglected the previous studies of education for Buraku youth. Under the Dōwa Special Measures Laws, enhancement of education was one of the goals of the Dōwa projects.8 Educational projects, such as improving educational facilities, assigning additional teachers to provide complementary teaching and providing financial aid to Buraku students were implemented in order to ensure the academic progress of Buraku students as well as to narrow the achievement gap between Buraku and non-Buraku students.

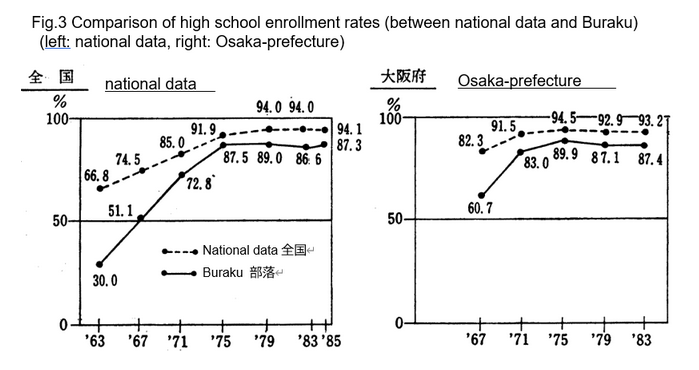

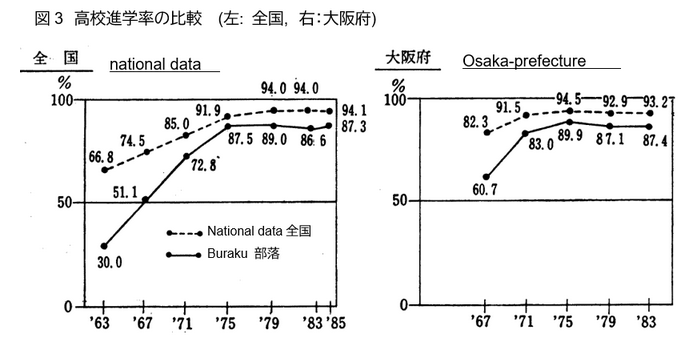

As a result of these efforts, together with the impact of rapid economic growth from the 1950’s through the 1970’s, high school enrollment rates of students from Buraku communities rose rapidly. Fig.3, based on data from the Ministry of Education and from a local board of education, shows the narrowing gap in high school enrollment rates between national rates and the rates in Buraku communities (Ikeda1987).9 The disparity was reduced, nonetheless leaving a small gap between Buraku and non-Buraku children. The author should engage with such public data before drawing far-fetched conclusions.

5. Use of the data in an ethically questionable way

The author uses ethically problematic data in this article, namely Zenkoku Buraku Chōsa (The national survey of Buraku communities, 1936). Ramseyer claims to have found the data on the internet posted by an “activist” individual. The author states in the text: “The data briefly surfaced in late 2015 (and were used in Ramseyer and Rasmusen, 2018)” (13).

The national survey of Buraku communities (1936) was originally conducted to obtain basic data for community improvement; however, the names and locations of Buraku communities appeared in the report and this data was later abused for conducting background checks. The Tokugawa outcasts formed their own communities according to their assigned official duties and occupations and many of these communities overlap with modern Buraku communities. Therefore, there is a possibility that the information on the location of the Buraku community can be used as a clue to identify the Buraku people. For this reason, people who try to exclude Buraku people from relationships with them such as marriage have sought this data.

This list of Buraku communities can also be used to track Buraku people who have moved out of the Buraku communities by comparing the names of communities in the list to the koseki (the Japanese family registration system). Ramseyer mentions: “Whether in the U.S. or Japan, virtually no professional lives within ten blocks of his natal home. If a burakumin moves more than those ten blocks, however, he ceases to be a burakumin” (21). However, this statement is contrary to the facts. By examining records of the koseki system, it is possible to identify Burakumin who live outside the Buraku communities.

The Buraku list posted by the “activist” on the internet is a copy of the research report prepared by the government-affiliated organization in 1936. In the 1970’s, detective agencies used this government report as a source to produce a directory of Buraku communities which the agencies sold underground at a high price to companies and individuals who wished to avoid Buraku people such as in time of marriage or of employment. It became a social problem at that time and the Ministry of Justice collected them and urged companies not to acquire said lists. The Zenkoku Buraku Chōsa which Ramseyer used as crucial data for the article was the original source for detective agencies to produce the directory of Buraku communities for background checks.

The census data posted by the “activist” was removed by a temporary court injunction in April of 2016, and a civil lawsuit was filed against the “activist”. The case is now pending. As Ramseyer states “the data briefly surfaced in late 2015” (13), but it is no longer available.

There are multiple problems when using these lists published on the Internet for academic treatises. The first is the problem of research ethics. This list can be used to identify Buraku people by comparing it to the koseki’s data and addresses. At Japanese research institutes, studies using this list are not likely to pass an ethical review.10

Second there is the question of the reproducibility of the data. As mentioned above, this Buraku list is currently restricted by the courts for viewing, and the data may not be reproduced by any third party.

Last but not least, the author cites a number of references to journalists and researchers to reinforce his theory in a way that is convenient for him while deliberately ignoring the substantial academic research published in different journals and monographs. He states that “Work on the modern buraku by serious Japanese scholars barely exists” (5). Instead, he seems to have ignored this body of work, leading to his many misinterpretations.11

Letter of Concern to the editors of the Review of Law and Economics

Akuzawa Mariko

Saito Naoko

はじめに

阿久澤 麻理子

このレターは、Ramseyer氏の論文に対し、異議を唱えるためだけではなく、日本の研究者たちに、ファクトチェックを呼びかけるために書かれた。部落問題に関わって来たすべての研究者にとって、声をあげることは、学問上の誠実さの問題である。問題の多い本論文のファクトチェックには、歴史学者、社会学者、その他の領域を専門とする研究者も必要である。最初のレターを書くことで、ボールを転がし始める役割を果たしたい、と考えた。

なお、このletter of concern は、Review of Law and Economicsの編集長宛に送付した後に、国際人権NGOであるIMADRのウェブにおいても全文を公開した。本稿は、The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus 掲載にあたって、レターの最後の部分に加筆修正を行った(末尾の注に明記している)。

また、このレターは単にアカデミックなコミュニティだけに向けて書かれたものではない。一般市民、そして部落コミュニティが、このような研究論文にアクセスする機会はない。だからこそ、著者の誤り・虚偽の証拠をより広い社会に知らせることは研究者の責任であり、危険な歴史修正主義に対する挑戦の一端を担うことでもある。

注目すべきは、同和対策事業の実施を裏付けて来た最後の特別法が失効してから、ほぼ20年近くが経過したこの時期に、著者が、部落民アイデンティティを「架空(fictive)」だと主張し、それを無意味化しようとしている点である。

特別法の下で、同和対策事業の対象となるためには、部落コミュニティ・部落出身者のエンパワメントとカミングアウトが前提であった。しかしながら法の失効後、多くの学校では、部落(コミュニティ、人)を特定することにつながる可能性のあることは、一切触れないようになった。法の裏付けがないのに、地域・人が特定されてしまうのは、誤りだと考えるようになったからである。

また、部落コミュニティでは、同和対策事業の実施が進むにつれ、教育や就職などにおいて人生の選択肢の幅が広がり、あるいは地区外出身者との結婚などにより、多くの人びとが地区から転出し、人口上の大きな変化が起こった。こうした変化は、物的にも、また心理的にも、部落と部落外のギャップが狭まってきたことの結果でもある。

一方、こうした変化によって、部落にルーツのある人びとのアイデンティティは多様化し、また若者世代では、家族のルーツを知らなかったり、教えられた経験のない者も多くなり、そのアイデンティティは弱くなっている。世代交代が進み、過去の差別の記憶や、解放運動にコミットしてきた経験を持つ年配者が少なくなることは、歴史的事実や合意を捻じ曲げ、転覆を企てる修正主義者からの攻撃を受けやすい、ということでもある。

最後に、このレターでは、著者が『全国部落調査』(1936)を使用していることの倫理的問題も指摘している。これは身元調査に利用された問題のあるデータである。2015年、ある人物が、そのデータを意図的にネット上にアップしたのだが、裁判所は2016年4月にこのデータの削除を求める仮処分決定を行い、その決定は上級審でも保持された。しかしながら、RLEはこの論文を2019年に公表している。編集委員会には、論文を審査するにあたって、部落問題の専門家はいなかったのだろうか。編集委員会は著者が使用したデータが、日本の裁判所によって削除命令を受けたものだと知っていたのだろうか。著者はそのことを編集委員会に知らせていたのだろうか。RLEの編集者は、この論文を出版したことについて大きな責任を負っている12。

学会誌編集者に向けたレター

2021年3月8日

Review of Law and Economics 編集長殿

私たちは、2019年の貴学会誌において、J. Mark Ramseyer氏による論文「でっちあげられたアイデンティティ・ポリティクス:日本の部落アウトカースト」(原題:“On the invention of Identity Politics: The Buraku Outcastes in Japan”が公表されたことに重大な懸念を表明するためこのレターを送っている。私たちは大阪市立大学人権問題研究センターで教育・研究に携わる者であり、大阪市立大学は、日本で初めて、部落差別問題の研究・教育に取り組むための専任教員を1970年に採用した大学として知られている。以来、人権のための研究と教育はこのセンターの使命であり、部落差別についての研究・教育は我々の仕事のなくてはならない部分である。

長年、部落差別についての研究に取り組んできた者の視点から見ると、この論文は、部落コミュニティの中から立ち上がった、社会運動の歴史についての誤った解釈に基づいて書かれている。著者は、戦後の同和対策事業が、国の法に基づいて実施されたことを無視し、部落における特定の運動団体の「ゆすりの戦略」によって、事業が行われたかのように記している。また、統計的データを誤用し、部落や部落コミュニティに対する著者の先入観に合致するような結論を導き出している。さらに『全国部落調査』(1936)のデータを利用していることの問題も、指摘されなければならない。

私たちは以下に、論文中の重大な問題のいくつかを指摘している。私たちは社会学者として、社会学の領域に焦点を当て、歴史的なことがらについての数多くの懸念は、歴史研究者に委ねることにした。以下は、問題点をすべて網羅していないが、あまりにもひどいものをあげている。これだけでも、編集委員会がこの論文を再審査するのに十分足りると信ずる。

ところで、ここでは、Ramseyer氏の部落問題についての研究への懸念を示したが、非常に問題のある研究によって、氏が批判を受けるのは初めてのことではない。The International Review of Law and Economicsに公表された氏の論文は、世界中の多様な学問領域の研究者から厳しい批判を受けている。Ramseyer氏による事実の誤った解釈、方法論における問題、引用に関わる問題、そして氏の先入観とは相いれないデータを意図的に無視しているような点にについて、数多くの研究者が疑問と懸念を表明し、当該の学会誌は、オンライン論文に「懸念の表明」を追記した。

研究者である私たちは、専門家としての基準と手続きを支持している。Ramseyer氏の部落問題についての論文は、最低限の学問上の誠意も示していない。それは、社会における信用・信頼を得られるように研究してきた社会科学者の、研究の信頼性を傷つけるものである。

阿久澤 麻理子

大阪市立大学 人権問題研究センター/都市経営研究科 教授

齋藤 直子

大阪市立大学 人権問題研究センター 特任准教授

以下のレターには5点の論点があるが、そのうち1−4の文責は阿久澤麻理子、5の文責は齋藤直子にある。

1. 同和対策に法的根拠があることを無視している

まず、著者は、同和対策事業の法・政策的プロセスを無視し、それが、あたかも部落の特定組織の「ゆすり」の戦略によってもたらされたかのように、誤った情報を読者に伝えている。実際には、総理大臣の諮問機関である同和対策審議会が、1965年に同和対策事業特別措置法の立法と政策を答申し、その法が政策を実施するための予算の根拠となった。最初の法は1969年に施行されている。すなわち、同和対策事業は最初から政府にその基盤をもつ政策的事業なのである。

2. 部落コミュニティにおける人口の変動についての誤った解釈

第二に、著者は明らかに日本語が堪能であるのに、日本語による最近の研究成果を無視しており、それは許されないことである。部落コミュニティにおける人口統計の変化に焦点をあてた研究例は数えきれないほどあり、また、コミュニティの変化を示した政府や自治体による公的データという「一次資料」もある。

それにもかかわらず、著者は部落の人口統計の変化を、同和対策事業によって生まれた「犯罪的な動機」に結び付け、信じがたい結論を引き出している。それは「国の補助金が、最も機会に恵まれない『部落民』に、部落に留まって『犯罪的なキャリアに身を投じる』というインセンティブを与え」、その一方で、「より良い合法的なキャリア選択が可能であった者たちは、部落コミュニティを見捨てて行った」というものである(p.1要約)。そして補助金が終わってこのようなインセンティブがなくなると、「部落のティーンエージャーは学業を継続するようになり、彼らは高校を卒業し、大学へ行くために部落を去り、二度と戻らなかった」と述べている(p.85)。

しかし、著者が何と言おうと公的データが事実を示している。図1は13、同和対策事業のための特別法の下にあった、1971年、 1975年、1993年の部落の人口構成を年齢階層別に示している。15歳未満の人口は、1971年には全体の24.1% であったが、1993年には16.2 %に落ちた。一方、65歳以上の高齢者の人口に占める割合は、1971年の7.2% から、1993年には15.5% に上昇している。

図2は、1993年時点での年齢階層別の人口構成を、部落と全国とで比較して示したものである。20~34歳の若者世代の割合は、部落においては相対的に低く、一方で55歳以上の人口の割合が高くなっていることがわかる。

これらの図は、同和対策が実施されていた期間に、若手世代が教育を終えた後に部落を後にし、その結果、地域に残った人口に占める高齢者の割合が高くなっていったことを示唆している14。ラムゼイヤー氏は、コミュニティに留まる部落民とは、「部落に留まって犯罪的キャリアに身を投じるという、かつてないほどの大きなインセンティブに直面した」人びとであったと書き(p.1 アブストラクト)、部落民の暴力的なイメージを強化している。あまりにも滑稽である。ラムゼイヤー氏は、部落コミュニティに住み続けている高齢者を暴力的で危険な人びとだと言わんとしているのだろうか?

また、大阪府が1990年に実施した「大阪府同和対策事業対象地域住民生活実態調査」(以下1990 年調査と記す)と、 2000年に実施した「同和問題の解決に向けた実態調査部落問題調査」(以下2000年調査) も、大阪府内における48の同和地区(行政機関による部落の呼称)地区の人口統計の変化の背景を示す、公的な「一次資料」である。大阪の部落は、大半を都市部落が占めているが、同和対策事業が終了する前の状況がわかる。

2002年に同和対策事業を裏付けて来た特別法が期限を迎える前の、1990年代後半からの移行期間には、すでに法や政策の変化が見られるようになっていたが、その一つが、1996年の、公営住宅法の改正である。これは、部落コミュニティからの人口の流出に大きな影響を与えた。

大阪府における部落コミュニティの人口は、1993年には111,435人であったが、2000年には95,468人まで減少した(15,967人の減少)。一方、2000年調査では、無作為抽出された15歳以上1万人の部落コミュニティの住民に対するアンケート調査を行っており、現住の部落以外の場所で生まれ、現住の部落に10年以内に来住した人びとが9.4%(n=7676)あった。もしこの割合を15歳未満も含めた人口にあてはめると、2000年の部落人口のうち、現住の部落の出身者でなく、かつ、10年の間に現住の部落に越してきた者が8,974人と推計できる(奥田2002).15

その上で奥田は、この同じ時期(1991~2000)に部落から転出した者の数も推計している。人口の自然増・減を無視すれば、その数は少なくとも24,941人である(10年間に減少した15,976人と、10年間に転入してきた8,974人を足す。転入者の数は転出者を埋めあわせたと考えられるから)。これは2000年人口の26.1%にあたる。

このような多数の転出は、1996年の公営住宅法改正によって、同和対策の一環として行われていた家賃補助が廃止されたことが、かなりの程度要因である。その後の家賃は世帯の収入の基準によってきまるようになったので、所得の高い世帯にとっては、居住し続けるには家賃が高くなり、転出を余儀なくされた16。空室は経済的に、より困難な状況にある人びとによって埋められることになった (奥田 前書; 内田他 2005).17 また、入居者募集が一般公募となったことからも、比較的新しい住民の多くが、一般世帯であると考えられる。

部落コミュニティの人口の変化を説明する多数の公的データがあるのだから、著者がこれらを完全に無視し、部落の人口移動を「犯罪的インセンティブ」に帰すことは、誤りである。

なお、いくつかの地方自治体では、同和対策事業の実施を裏付けてきた特別法が期限を迎えた後も、部落コミュニティの状況を把握するためのデータ収集を継続していることも情報として付記しておきたい。例えば兵庫県たつの市では2020年に調査を実施し、その結果はニュースメディアでも取り上げられたから、広く知られている。また、大阪府、和歌山県、福岡県でも国勢調査のデータを使い、かつての同和対策事業の対象地域の状況の把握を行っている。これらの公的データの中には、著者が参照することができたものもある。

3. 統計の誤用

著者は自分の先入観に合った結論を引き出すため、非常に問題のある指標である「部落民PC」(部落民の数を全人口で割ったものと説明されている)を作り、これを重要な変数として使っている。しかしながら、1993年の部落民の割合と、その他の社会現象を示す指標(それも20年近く後のデータ)との相関を都道府県のレベルで見るというのは(p. 27)、合理的なことであろうか? 部落民PCと、その他の変数、例えば、一人当たりの犯罪件数(2010)、一人当たりの覚せい剤関連犯罪件数(2011)、生活保護率(2010)等々が相関することから、部落民の割合は、機能不全の行動と関係がある、と著者は述べている(P.27)。だが、1993年の部落民の、都道府県人口に占める割合は、ゼロから0.289 %であるから(p.23 表3)、この論文は、著者も自ら認めているように「生態学的誤謬を犯すリスク」(p.22)のきわめて高いデータを使って、部落に対する非常にひどいイメージを作り出しているとの批判に直面しなければならない。

また著者は再び、「部落民PC」という指標を論文の後のほうでも使用している(例えばp.52)。1907年の部落民PCが、犯罪PC(全犯罪数を全人口で割る)、殺人PC(全殺人件数を全人口で割る)と関係しているから、著者は「都道府県単位で部落民の割合が高くなれば、一般的な犯罪の割合も、とくに殺人の割合も高くなる」(p.52)と述べている。しかし、部落と部落外の犯罪や殺人の件数を区分もせずに、このように記すことは、著者が告白しているように「生態学的誤謬」(p.51)のリスクがあまりに高い。明らかに著者自身も生態学的誤謬を認識しているにも関わらず、実証のない主張を続けているのである。

4. 部落の若者の進路に関する誤った説明

著者は、同和対策(国の補助金)が「若い部落民の男性に、学校を中退し、部落に留まり、犯罪シンジケートに加わるよう仕向けた」と記しているが(p.77)、これも、同和対策が部落の若者の進路を犯罪に向かうよう促したかのように、読者を誤った方向に導いてしまう。

再び、著者が日本語に堪能であることを考慮するなら、部落の若者の教育に関わる膨大な先行研究の蓄積を著者が無視したことはたショッキングである。同和対策事業特別措置法の下では、教育の充実は目的の1つに位置づけられ18、教育施設の充実、教員の加配と補習、部落の生徒への経済的支援など、部落の子どもたちの学力の向上、部落内外の学力格差の縮小のための取組みが行われた。

こうした取組みの結果、また1950年代から70年代の日本における高度経済成長もあいまって、部落の若者の高校進学率は急速に上昇した。文部省の統計と、地方教育委員会(注:大阪府)のデータをもとにした図3からは、全国と部落の高校進学率の格差が縮まっていったことがわかる(池田 1987)19。但し、格差は縮まったが、部落内外にわずかな差が残された。著者は、極端な結論を出す前に、公的データを参照すべきである。

4. 倫理的に疑わしい方法でのデータの使用

本論文において、著者は倫理的に問題のあるデータ、すなわち「中央融和事業協会 全国部落調査」(1936)を使用している。Ramseyer氏は、ある「活動家」によって投稿されたインターネット上のデータを見つけたと述べている。著者は、本文において以下のように述べている。「データは2015年末に、一時的に明るみに出た(そして、2018年のRamseyer and Rasmusen論文にて使用した)」(13ページ)。

「全国部落調査」(1936)は、本来は部落改善のための基本的な情報を得るために行われたのであるが、その報告書には部落の地名と所在地が記載されており、後にこの情報は身元調べに悪用された。徳川時代の賎民は、役負担と職業にしたがってそれぞれのコミュニティを形成していたが、それらの多くは現代の被差別部落と重なっている。したがって、部落の所在地情報は、部落出身者を特定する手がかりとして使用される可能性がある。そのような理由から、結婚などの人間関係から部落出身者を排除しようとする人は、「活動家」が投稿したような情報を求めた。

この部落のリストは、記載されている地名と、日本の家族登録制度である戸籍とを対照させることによって、部落から転出した部落出身者を追跡することにも利用される可能性がある。「米国であっても日本であっても、生家から10ブロック以内に暮らす職業人は、事実上いない。しかし、もし部落出身者がその10ブロックを超えて移動したなら、彼は部落出身者ではなくなるだろう」(21ページ)とRamseyer氏は述べる。しかしこの意見は、事実と異なる。戸籍制度を悪用すれば、部落の外で暮らす部落出身者を追跡することは可能である。

「活動家」によってインターネットに投稿された部落リストは、1936年に政府の関連組織が作成した調査報告書のコピーである。1970年代、探偵業者は、この政府報告書をもとに「部落地名総鑑」を作成し、結婚や雇用の機会に部落出身者を避けようとする企業や個人に向けて、秘密裏に高額で販売した。

当時、そのことは社会問題となり、法務省は上述のリストを回収し、また企業に向けてこれらのリストを入手しないよう要請した。Ramseyer氏が論文の重要な情報源として使用した『全国部落調査』は、探偵業者が身元調査のために作成した部落の地名リストの元となったものである。

「活動家」によって投稿された部落調査は、2016年に裁判所の仮処分によって削除され、「活動家」に対し民事訴訟が提起された。現在、裁判で係争中である。Ramseyer氏が「データは2015年末に、一時的に明るみに出た」(13ページ)と述べているように、現在は閲覧できない。

インターネット上で公開されたこのようなリストを学術論文において使用することには、さまざまな問題がある。第一は、研究倫理の問題である。このリストは、戸籍の情報や住所と照合することによって、部落出身者を特定することに利用される可能性がある。日本の研究機関においては、このリストを使った研究は倫理審査を通過しない可能性が高い20。

二点目に、データの再現性の問題がある。上述のように、この部落リストは現在、裁判所によって閲覧が制限されており、第三者によってデータを再現することはできないだろう。

最後に、著者は自説を補強をするために、ジャーナリストや研究者のいくつかの文献を非常に都合のよい形で引用する一方、「日本の真面目な研究者による現代の部落に関する研究は、ほとんど存在しない」(5ページ)として、さまざまな雑誌や単行本に掲載されている相当数の学術研究を意図的に無視している。これらの一連の研究を無視しているために、ラムザイヤ氏は数多くの解釈の誤りを犯しているように思われる21。

Notes

Yokohama District Court stated on July 17th, 2017, “Under current conditions, disclosure of such information will inform the wider public of the location of districts formerly designated as Dōwa areas and will facilitate background checks to determine whether a particular individual has a Buraku origin or not”.

Both fig.1 and fig.2 are in Noguchi, et. al. (1997) Konnichi no Buraku Sabetsu『今日の部落差別』 p. 33. Buraku Kaihō Shuppansha. Both figures are based on the national census of Buraku communities, and on the national population census, both conducted by Management and Coordination Agency(総務庁)of the Japanese Government.

According to the National Census of Buraku communities in 1993, the last government survey to assess the conditions of the communities, the percentages of high school graduates went up among the younger generation: 7.5% (age 70-74), 14.0% (60-64), 23.0% (50-54), 52.4% (40-44), 80.2% (30-34), and 81.1% (20-24). Those below 34 years of age, born after 1959 and above 10 years old when the national Special Measures Project started in 1969, could benefit from the national Special Measures assistance when they were in elementary education. In addition, national scholarships for high school students in Buraku communities started in 1966 (before the Special Measures Law) and some local governments even had their own scholarships prior to the government project. Those scholarships supported the education of those who were in their 40s at the time of the survey.

At the time of the 1993 National Census, 13.2% of households had one or more family member(s) under 30 years old who moved out and lived outside of their Buraku community. The most popular reason for the move of the younger generation was marriage (47.6%), followed by “employment” (31.9%) and education (11.4%, including 7.8% for enrollment in higher education).

According to Okuda(ibid), in the case of Osaka prefecture in 2000 the middle income households in Buraku communities (annual income between 4,000,000 and 6,000,000 JPY) had to pay rent for public housing equivalent to the market rate, as a result of the amendment of Public Housing Law. Okuda concluded that this amendment would accelerate the outmigration of those financially stable households.

Uchida, Y., and Otani E. (2001) Tenkanki niaru Dōwa Chiku no Machizukuri ga Kongo no Nihon no Machizukuri ni Shisa Surukoto「転換期にある同和地区のまちづくりが今後の日本のまちづくりに示唆すること」in the Journal of City Planning Institute of Japan. Vol.30.『第36回日本都市計画学会学術論文集』pp.109-114

An ecological fallacy is a formal fallacy in the interpretation of statistical data that occurs when inferences about the nature of individuals are deduced from inferences about the group to which those individuals belong.

The goals of the Dōwa Special Measures Projects were listed in the article 5 of Dōwa Special Measures Law of 1969: improvements in living conditions, promotion of social welfare, promotion of industry, stabilization of employment, enhancement of education, and strengthening of activities for human rights protection.

Ikeda, H. (1987) Nihon Shakai no Mainoriti to Kyōiku no Fubyōdō 「日本社会のマイノリティと教育の不平等」in the Journal of Educational Sociology. Vol.42.『教育社会学研究』第42集 pp. 51-69

Universities and research institutes in Japan have established codes of ethics regarding “research on human subjects,” and have set up ethics committees. As already mentioned, the list of the locations of Buraku areas is currently not available for inspection due to a provisional disposition by the court. The use of such a list for research purposes would not be permitted by the ethics committees of Japanese universities and research institutes, as it would be judged to have significant ethical and social implications, and to be highly detrimental to the Buraku people.

The following, a supplementary explanation to the above final paragraph, was added when the letter was posted on the IMADR website. The final paragraph of this letter was modified in line with the following supplementary explanation: “While Ramseyer ignores academic articles on contemporary Buraku issues claiming that there are no ‘serious researchers,’ he constructs his article by conveniently “citing” only those books read by general readers for the purpose of reinforcing his ideas. The final paragraph explains how Ramseyer tactically ignores those academic articles and is not meant to assess the value of the introductory books and reportage cited.

横浜地方裁判所相模原支部(2017.7.11)は異議審決定(本訴民事訴訟の被告の不動産仮差し押に関わる異議審決定)において「かかる情報が広く一般に知られることは、現状において、かつての同和地区の所在地が広く知られることを意味するのであって、それによって、特定の個人が同和地区出身者もしくは居住者であるか否かを調査することを著しく容易にするものである」と述べている。

1993年の同和地区実態把握等調査によると、若い年代層ほど中等教育以上の最終学歴を持つ割合は多い(70-74歳で7.5%、60-64歳で14.0%、50-54歳23.0%、40-44歳52.4% 、30-34歳80.2%、20-24歳81.1%)。調査当時の34歳は1959年生まれで、同和対策事業特別措置法施行年(1969)には10歳となるから、初等教育の間に特別施策が始まっている。なお奨学金は1966年に始まり、自治体によってはそれより早くに制度を設けたところもあり、40歳代の教育を支えたといえよう。ところで、1993年の調査当時、13.2%の世帯が「世帯に30歳未満の転出者がいる」とk耐えており、その理由は結婚(47.6%)が最も多く、就労(31.9%)、就学(11.3%)が続く。就学の11.3%には、短大・大学(7.8%)が含まれる。

奥田(同書)によると、大阪府2000年の段階で、年間所得400~600万円の中堅所得世帯は、応能応益家賃制度の導入によって市場並みの家賃を払うことになる。奥田は「中堅所得層の転出に拍車がかかる」と述べている。

日本の大学や研究機関においては「人を対象とする研究」に関する倫理規定を設け、倫理委員会を設置している。すでに述べたように、部落の所在地に関するリストは、現在、裁判所の仮処分によって閲覧ができない。このようなリストを研究に用いることは、倫理的及び社会的な影響が大きく、また部落の人々の不利益が高いと判断され、日本の大学や研究所の倫理委員会は許可しないだろう。

なお、レターがIMADRのウェブサイトに掲載された際、上記の最終段落の補足説明として以下を追記した。本稿では、この補足説明に沿って、最終パラグラフを修正している。

【注記】最終パラグラフについて補足説明する。Ramseyer氏は、「真面目な研究者」が存在しないとして 現代の部落問題に関する学術論文を無視する一方、自身の考えを補強するための素材として、 一般読者を想定した書籍だけを非常に都合のよいかたちで「引用」して論文を構成している。このパラグラフは、Ramseyer氏が学術論文を巧妙に無視していることについて指摘しているのであり、引用された入門書やルポルタージュの価値について評価をするものではない。