Introduction

In the book, Summoned at Midnight: A Story of Race and the Last Military Executions at Fort Leavenworth (Beacon Press, 2019), Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, Richard A. Serrano revealed the racial injustices of the US military justice system. Between 1955 and 1961, a number of black and white prisoners were incarcerated on death row at Fort Leavenworth military prison, Kansas, but ultimately all the white prisoners were paroled and only African-Americans were hanged.

Summoned at Midnight: A Story of Race and the Last Military Executions at Fort Leavenworth by Richard A. Serrano, Beacon Press, 2019.

Summoned at Midnight contained groundbreaking research – Publishers Weekly, for example, called it, “An important contribution to the historiography of race and justice” – but the book also included one important revelation which was largely overlooked at the time of its release. Serrano had uncovered the final fate of one of the most infamous criminals in post-war Okinawan history: Sergeant Isaac J. Hurt. In September 1955, Hurt had raped and murdered a six-year old girl, then abandoned her body on a garbage dump in a crime which became known as the Yumiko-chan Incident. The killing triggered outrage and Hurt’s court-martial on Okinawa received widespread media coverage, but despite this public attention, one key point remained hidden for more than six decades: what had actually happened to Hurt following his trial?

Serrano investigated Hurt’s case by interviewing the men who had guarded him at the Fort Leavenworth prison, and tracking down courts-martial records and letters at the National Archives and Presidential Libraries. What he unearthed paralleled his other discoveries in Summoned at Midnight; on Okinawa, too, racial politics strongly impacted the military justice system and shaped how perpetrators were eventually treated.

It is with great appreciation that we acknowledge the permission of Beacon Press and Richard A. Serrano allowing The Asia-Pacific Journal to publish the following excerpt from Summoned at Midnight. It is hoped that many more people will be made aware of this important investigation. After the excerpt, there is a brief epilogue which includes reactions from residents of Okinawa Prefecture and why the murder remains so raw in the minds of those on the island sixty-six years later today. (Jon Mitchell)

* * *

Isaac Jackson Hurt and the Yumiko-chan Incident

Sergeant Isaac Jackson Hurt died not at the end of an army rope in Kansas but in a comfortable VA hospital in Ohio. On death row, most everyone thought him aloof and cold-hearted. He was tall, thin, and quiet. Later, as a free man, he worked as a night watchman. His new bride cherished him as a “law-abiding, good and moral citizen.” One president commuted his death sentence, and another president set him free.

Isaac J Hurt at Fort Leavenworth military prison, Kansas. (Courtesy Richard A. Serrano)

He was arrested in September 1955, accused of the rape and murder of five-year-old Yumiko Nagayama in Okinawa. Her assailant had sliced open her abdomen with a knife and abandoned her body in a beach quarry garbage dump near the China Sea. Her slaying drew uproars over what is still known today as the “Yumiko-chan Incident.” Crowds marched down city streets in protest. Several other females had been raped by American GIs, and after Yumiko died, another soldier attacked another child. “Every Okinawan is burning with indignation!” cried the Okinawa Shimbun newspaper.

Until then, Okinawans had been counseled not to resist their occupiers. “Do not be anti-American,” they were warned. “Do not be angry or criticize, do not talk too much, never lie, always be truthful…. Never put your hands above your ears, do not shout, speak calmly.” But Yumiko’s murder lifted their voices in anger.

A student activist named Irei believed fears of repression would never end until the Americans left their homeland. “In tears,” he said, “my university friends and I discussed that these incidents were evidence of racial insult. I was convinced that these crimes would never disappear unless we recover our human rights.”

Many demanded that the United States “punish offenders of this kind of case with the death penalty,” singling out Hurt. It marked the first meaningful anti-American protests in a decade. Ten years earlier, the island had been ravaged by Japanese and American troops fighting over the string of beaches and coral reefs. The battle for Okinawa cost more than two hundred thousand lives, soldiers and civilians alike, including a third of the island population. Up to ten thousand Okinawan women had been raped.

Two weeks after the girl’s murder, Major General James E. Moore spoke in a packed community hall and offered his “deep sympathy” to a community relations advisory council. He promised change, suggesting restricting or ending altogether his soldiers’ leave time. But Okinawans knew their economy would suffer if GIs were banned from shops and restaurants. The general also admonished the more strident activists. To suggest that Americans condoned violence, he cautioned, “is an insult to the American people.” And he strongly defended the army’s judicial system. “There never has been an attempt at whitewashing or covering up any case,” General Moore declared.

Mitsuko Takeno, president of the Okinawa Women’s Association, argued that the army should immediately turn Hurt over to Okinawan justice. “If this act was committed by an Okinawan, the people would probably surround his house and stone it and indignation will reach its peak and they will probably lynch this person,” she warned. “But because of the fact that it was committed by an American, nothing has taken place so far.”

Homer Davis, the Leavenworth lawyer who later represented Hurt on appeal, said Hurt should have been either tried in the Okinawa courts or moved to a military courtroom in the States. “The natives raised so much hell because it was one of many rapes our soldiers perpetrated over there,” Davis recalled. “People were holding rallies, 5,000 at a time.”

Before the court-martial began, Hurt’s army lawyer, Captain Julian B. Carrick, asked that the soldier from Kentucky be returned stateside for trial. He cited “the hostile attitude of the Okinawans” and insisted their anger “prevented a fair trial” there.

Before his arrest, Hurt had swilled some twenty beers and partied with prostitutes. When army police caught him, he asked for a cigarette (his brand was Lucky Strikes), and he teased the investigators. “I read the newspaper about the girl’s killing,” he quipped. “I feel I might have been the one. It could have been me.”

At his court-martial, the prosecution’s best witness was a scared nine-year-old boy. He had seen a GI who looked like Hurt near the quarry but could not identify Hurt in a lineup. Yoshiko Kamimura, a waitress, testified about bloodstains on Hurt’s pants. Hair samples were lifted from the door handle and seat cover in the sergeant’s rusted-out green-and-white Ford, but none matched the girl or tied Hurt to the slaying. The best a Japanese professor could say was that the hairs “could be” hers. Even on death row, Hurt still fixated about the hair residue. “He swore they never really proved it on him,” recalled social worker Thompson. “He was always talking about hair samples.”

The trial wore on for two weeks. In December 1955, Sergeant Hurt was convicted and sentenced to die. He barely blinked. But his lawyer, Captain Carrick, immediately asked for a reconsideration and leniency. He presented letters and petitions from Hurt’s hometown of Lothair in the coal-mining country of southeast Kentucky. They described him as “honest” and “law abiding.” Prosecutors countered with an affidavit showing the thirty-one-year-old officer earlier had served eleven months in prison for assault and attempted rape in Detroit.

In a private session with the staff judge advocate, Hurt insisted he was innocent. He charged that witnesses had lied or based their testimony on press accounts. He leaned into the judge and claimed, “I didn’t do it.”

He said little on death row. “He was very intoxicated over there and couldn’t remember much about his crime,” recalled Sergeant Peterson. He never received mail from home. “Once they had a flood in Kentucky and he said maybe the damned place washed away, remembered Sergeant Ray. “He said that was why he never heard anything from his people.”

His military appeals failed, but Hurt and his relatives in Kentucky managed to gain the ear of Kentucky politicians. Representative Carl D. Perkins, a Kentucky Democrat and World War II army veteran, wrote the White House. He described the growing concerns from his district where Hurt “comes from” that “something could be done about” commuting the sentence.

In the Senate, Thruston B. Morton, a Kentucky Republican, personally forwarded a Kentucky VFW resolution to the Eisenhower administration, urging a commutation. “The conviction rests upon circumstantial evidence and there exists some doubt concerning the guilt or innocence of the accused,” the VFW warned.

Senator John Sherman Cooper, another Kentucky Republican, pressed the White House on the hair samples. “Give this matter your deepest consideration,” he urged the president. “The death sentence is one that should be very carefully meted out; it is so irrevocable.”

Senate Majority Leader Lyndon Johnson and Senator Ralph Yarborough, Texas Democrats, asked a law firm to pursue Hurt’s appeals. Texas lawyer Robert J. Hearon Jr. warned White House assistant counselor Phillip Areeda that executing Hurt “might very well constitute a manifest miscarriage of justice.”

A brace of political muscle from powerful office holders from two Southern states united to support this otherwise nondescript Kentucky native. He was a local boy, one of theirs, and once protests over the Okinawan slaying erupted into international anti-American outcries, they rushed to defend this white American sergeant.

But in May 1959, Army Secretary Wilber Brucker recommended death. “I have studied this case carefully,” Brucker said. “And I am convinced of the guilt of the accused.” He also was disgusted that Hurt had falsified his enlistment papers by not mentioning the earlier assault case in Detroit.

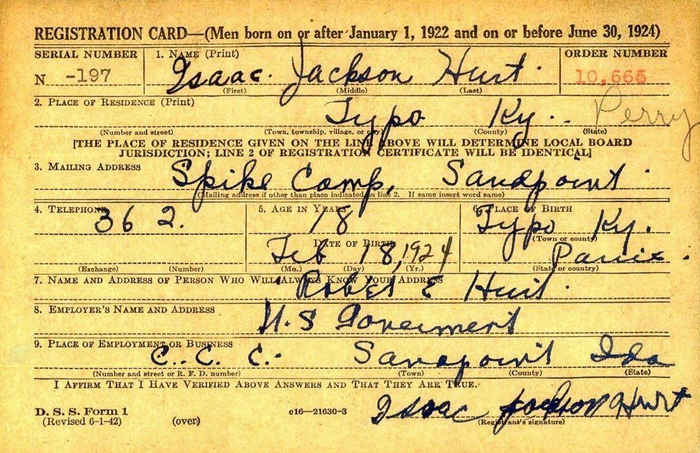

The WW2 draft card of Isaac J Hurt. (US National Archives)

Hurt’s supporters kept pushing, though. Judge S. M. Ward of Hazard, Kentucky, worked with Hurt’s parents for a commutation. “The father of this serviceman is eighty-eight years of age and his mother is seventy-seven,” Kentucky Republican representative Eugene Siler told Eisenhower. “They have not seen their son for more than six years.”

Homer Davis tried to win a new trial. At a federal court hearing in Kansas, he brought up the outrage in Okinawa and the failed defense attempts to move the court-martial off the island. “This was a sham, a pretense of a fair trial.” Davis argued. But the judge was unimpressed and rejected the appeal. Prison guards who brought Hurt to the Kansas City, Kansas, courthouse in a six-jeep convoy returned him to death row at Fort Leavenworth on what now seemed the end of the road.

The Eisenhower White House was beginning to buckle under the weight of Hurt’s influential supporters. Hurt had never truly confessed. No eyewitness placed him with the girl. His whereabouts that night was unexplained; even the drunken Hurt could not remember. And the hair samples did not match. The attorney general began to feel the death penalty was “inappropriate” and called instead for a long prison sentence. Such a circumstantial case, he suggested, would seem to “justify” executive clemency. Areeda in the White House gnawed at his own doubts. “One can hold Hurt guilty only with reservations,” he reasoned.

On June 1, 1960, Eisenhower struck down the death sentence and gave Hurt forty-five years in prison, with no parole. Hurt was moved upstairs and, in the years ahead, served as an administrative trustee at the Fort Leavenworth prison. Later transferred to the federal penitentiary next door, he suffered a stroke in 1969 while playing handball. Hurt lost the use of his right arm and leg and hobbled with a cane around the prison yard, but still kept challenging his forty-five-year sentence.

“The way things are there is nothing to hope for me,” he wrote the warden. He wrote to the pardon attorney, the Senate, and President Ford’s attorney general, pleading for dismissal of his case or at least parole. “I can only believe that I was sacrificed to appease the dissident political elements who were demanding an end to American mil. Occupation,” he wrote, still haunted by the anger of the Okinawa protests surrounding the murder.

In January 1977, President Ford made Hurt parole eligible. Hurt limped out of prison, and by November, he began vocational training at the Goodwill center in Cincinnati. He worked as a night watchman, and in 1981, he married. A year later, his bride, Lura, a kitchen helper, mailed papers to Washington trying to win him a full presidential pardon. He was still waiting for word when he died in August 1984 at the VA hospital.

From Summoned at Midnight: A Story of Race and the Last Military Executions at Fort Leavenworth by Richard A. Serrano. Copyright 2019 by Herbert Marcuse. Reprinted with permission from Beacon Press, Boston Massachusetts.

* * *

Epilogue

On 23 September 2021, The Okinawa Times published an article featuring details of Serrano’s investigation into the parole and release of Hurt; many readers in Okinawa and Japan learned for the first time that Yumiko-chan’s murderer had been set free.

Among those reacting with anger to the news was Takazato Suzuyo, co-chair of the group Okinawa Women Act Against Military Violence, who said she was particularly aggrieved by Hurt’s claim that he had been sacrificed for political reasons: “I think that kind of consciousness still exists in the US military. The predisposition of the US military to look down on the citizens of the prefecture is really unforgivable.”

Takazato also stated, “The US military is still protected by the US-Japan Status of Forces Agreement. On the other hand, the human rights of Okinawans aren’t protected. Is it okay for such an abnormal situation to exist?”

Miyagi Harumi, a researcher on the history of Okinawan women, said she had been angered by the Japanese government’s emphasis that the crime was the personal responsibility of Hurt, suggesting it overlooked the larger, structural problem of the vast US military presence in the prefecture. Miyagi, who was born in the same year as the six-year old victim, said, “It could have been me – I think it was a crime that could happen to anyone at any time. US military-related incidents have occurred repeatedly and have been left unchecked.”

Accompanying the Okinawa Times article, a commentary discussed why the Yumiko-chan Incident is still relevant in the Prefecture, which continues to host 70% of the US military presence in Japan. Female Okinawans bear the brunt of military violence; Takazato and her colleagues have recorded hundreds of incidents of sexual violence committed by military personnel since WW2, a problem highlighted by the rape and murder of a 20-year old Okinawan woman by a former Marine in 2016. In the prefecture, as elsewhere in the world, the US military justice system remains opaque and little information is made public regarding courts-martial or punishment of service members.

Hurt’s case also points to how US elected officials prioritize the rights of military personnel over the lives of Okinawans. Despite Hurt having been found guilty of the rape and murder of a six-year old girl, he received the support of Senators, two sitting presidents and a future president. Today, similar priorities are visible in the Japan-US Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) which often shields Americans who commit crimes against Okinawans from punishment under Japanese laws. According to SOFA, the US military is granted jurisdiction over service members suspected of committing offenses while on duty, only requiring them to be transferred to the Japanese police after charges have been filed. The system has hindered Japanese investigations into military crimes and the problem has been exacerbated by Japanese prosecutors’ reluctance to indict SOFA-protected suspects.

Emphasizing such ongoing injustices was one additional detail of Hurt’s case uncovered by Okinawa Times: today Hurt lies buried beneath an official grave marker provided by the Department of Veterans’ Affairs (VA). The marker, in Reading Cemetery, Hamilton County, Ohio State, cites his WW2 service in the US Navy prior to his subsequent enlistment with the Army on Okinawa, with no mention of the latter.

The VA-provided grave marker of Isaac J Hurt at Reading Cemetery, Hamilton County, Ohio State.

(Courtesy Hamilton County (Ohio) Genealogical Society)

According to the VA’s guidelines, such markers ought not to be provided to service members dismissed from the military under dishonorable discharges. Commenting on the matter to Okinawa Times, Les’ A. Melnyk, Chief of Public Affairs and Outreach at the VA’s National Cemetery Administration, confirmed that “discharge under certain circumstances, including discharge or dismissal due [to] the sentence of a general court-martial, precludes entitlement to VA benefits. In addition, Veterans or Servicemembers who committed a capital crime or certain sex offenses may also be barred from receiving burial and memorial benefits.” Melnyk said the VA was actively reviewing the case and would take necessary steps if it determined the marker had been provided in error. No further information about VA findings was available at the time of completion of this article on November 9, 2021.

* * *

Notes on the excerpt

Information about Isaac Hurt’s murder of a child in Okinawa, his trial and appeals, the public outcry, and the US Army’s public response are drawn from Court-Martial Reports: Holdings and Decisions of the Judge Advocates General, Boards of Review, and United States Court of Military Appeals, Volume 22, 1956-1957, 630-37, Volume 23, 1957, 573-80, and Volume 27, 1958–1959, 3-60, in the Law Library at the Library of Congress, The uproar and protests in Okinawa are also covered in Miyume Tanji, Myth, Protest and Struggle in Okinawa (London: Routledge, 2006), 70-71; Yuki Takauchi, “Rape and the Sexual Politics of Homosociality: The U.S. Military Occupation of Okinawa, 1955–56,” part of the History of Asian Sexualities Series, on NOTCHES, a collaborative and international history of sexuality blog.

Davis, author interview, 1987.

Thompson, author interview, 1987.

Peterson, author interview, 1987.

Ray, author interview, 1987.

The extraordinary pressure from Kentucky and Texas politicians on behalf of Hurt is evident in letters stored among the Eisenhower Presidential Papers. Representative Carl D. Perkins wrote the White House on January 15, 1959; Senator Thruston B. Morton forwarded the VFW letter to the White House on January 29, 1959. The VFW statement was dated January 17, 1959. Senator John Sherman Cooper pressed the White House on June 30, 1959. Texas lawyer Robert J. Hearon Jr. wrote the White House on July 24, 1959, and August 4, 1959; on August 7, 1959, he advised that Texas politicians were engaged in Hurt’s behalf as well. Representative Eugene Siler lobbied the White House on October 28, 1959.

Homer Davis’s argument at the federal court hearing in Kansas City, Kansas, was delivered on December 28, 1959, and reported by the Kansas City Star on December 28, 1959, and the Kansas City Times on December 29, 1959.

Internal White House memos, including assistant counselor Phillip Areeda’s doubts about the death sentence and Army Secretary Wilber Brucker’s approval of death, are available among the Eisenhower Presidential Papers.

Hurt’s petition for a “Commutation of Sentence” in which he claimed he was “sacrificed” to quell the Okinawa protests, was signed August 11, 1975. It is available at the National Archives.

Lura Hurt’s “Character Affidavit” to win her husband a full presidential pardon was dated July 8, 1982, and is at the National Archives.

From Summoned at Midnight: A Story of Race and the Last Military Executions at Fort Leavenworth by Richard A. Serrano. Copyright 2019 by Herbert Marcuse. Reprinted with permission from Beacon Press, Boston Massachusetts

* * *

Asia-Pacific Journal would like to thank those who assisted the publication of this article: Richard A. Serrano, Jill Dougan, Abe Takashi, Sharon Morris, Heather Bowser, Mark Steinke, and Mark Selden.

* * *

Related articles

Terese Svoboda, Race and American Military Justice: Rape, Murder, and Execution in Occupied Japan

Takazato Suzuyo, Okinawan Women Demand U.S. Forces Out After Another Rape and Murder: Suspect an ex-Marine and U.S. Military Employee

Jon Mitchell, U.S. Marine Corps Sexual Violence on Okinawa