As a historian of premodern Japan active on Twitter, I seldom find myself embroiled in controversies in real time. I occasionally get pushback when I discuss the legacy of female emperors or nationalistic myths of ethnic homogeneity, but by and large, there’s little trouble. So I hardly expected any powerful backlash in February of 2021 when I retweeted an article in The New Yorker by Harvard Law School professor Jeannie Suk Gersen on a contentious publication regarding comfort women. In the tweet I had simply remarked “This is a fabulous summary of how this event unfolded across media and academic circles, also placing the major issues in historical perspective.” The result, however, was a ferocious Twitter storm from historical denialists that came to absorb my life and the lives of a number of my colleagues for months thereafter.

Far from existing solely in online spaces, the vicious attacks on scholars (and their supporters) continue to endure and are indicative of broader patterns of internet-based harassment that many academics have faced in the last decade. These attacks can affect the personal lives and professional careers of any academic or institution, regardless of their level of public interaction. In what follows, I outline how this particular controversy over Japan’s wartime atrocities unfolded, traveling from the digital pages of a journal into extremist online communities and, eventually, permeating the lives of digitally-engaged academics.

As information wars rage across social media, it is imperative that researchers and their institutions take seriously the public-facing engagement and scholarship increasingly demanded of academics at all career stages, at schools large and small. We are in an era when “fake news” and the widespread distrust of higher education threaten to eclipse the rigorous work that researchers do. Recent denialist stances on comfort women history and the fallout from their propagation in virtual spaces demonstrate that it is critical for humanities and social science specialists alike to understand digital modes of engagement, appreciate their real world implications, and fight for the integrity of knowledge. These are the tools with which educators can mobilize to combat persistent untruths, effectively serve the public, and fulfill our responsibilities as researchers and educators, whether the battlefield is on or offline.

“Contracting for Sex in the Pacific War” Across Media

On December 1, 2020, the digital version of a forthcoming article by J. Mark Ramseyer, Mitsubishi Professor of Japanese Legal Studies at Harvard University, was published online in the International Review of Law and Economics (IRLE). Entitled “Contracting for Sex in the Pacific War,” this eight-page article argued that women enslaved for sex during World War II by the Japanese military—known euphemistically as “comfort women”—were highly-paid, voluntary actors who entered into prostitution through a system of contracts they could freely leave after 1-2 years. Using the idea of “credible commitments,” a logic from game theory, Ramseyer asserts that contracts were used to incentivize women to voluntarily engage in dangerous and disreputable overseas work for advantageous wages; that is, he argues that “brothels could not—and did not— trap or imprison all or even most of the women,” and “they chose prostitution over… alternative opportunities.”1

Ramseyer reiterated these claims in a January 12 op-ed in the right wing news site JAPAN Forward, an English outlet of the conservative Sankei newspaper, in which he referred to the idea that comfort women were sex slaves as “pure fiction.” On January 28, Sankei itself ran a Japanese-language article that lauded Ramseyer as a “giant” of Japanese research whose findings, “having passed through peer review by other specialist researchers,” have great significance to arguments that comfort women were never trafficked. Ramseyer’s assertions, which run counter to decades of survivor testimonies and Japanese and international scholarly research, immediately began to attract attention.

News of these publications spread rapidly, first across Korean media outlets, then Japanese. Finally, they hit English-language media. As historians expressed their shock that such a paper ever saw the light of day, a swell of media coverage followed across a wide range of outlets through February, March, and April, from university newspapers to international news sources like CNN and The New York Times as well as more popular online platforms like Vice and Jezebel. Two US Congresspeople expressed their anger on Twitter, with Young Kim (CA) calling Ramseyer’s work “untrue, misleading & disgusting” and Marilyn Strickland (WA) writing that his claims were “misleading & deplorable.” The Chinese government reaffirmed their condemnation of denying war atrocities at a February 19 press conference, where Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Hua Chunying responded to a question about Ramseyer’s paper and the comfort women issue at large, stating “China opposes all erroneous acts that whitewash the war of aggression in an attempt to deny and distort history.” Academic and professional organizations including the Reischauer Institute of Japanese Studies at Harvard University and a coalition of fifty historical societies and organizations in Korea, among others, issued statements; over 3,000 professors of economics and law signed a letter of concern about the article’s misuse of theory to make unverifiable historical claims; and, on social media, scholars of Asia began to find one another and mobilize.

When news of Ramseyer’s article appeared, the ability of information to spread swiftly on Twitter fast-tracked its circulation through academic circles. Almost immediately, researchers in Asian Studies who had seen one another tweet on the issue were in contact, emailing colleagues, and sharing a Google Doc fact-checking every citation in the original publication. One of the first scholarly refutations published was a devastating 36-page fact-check first released on February 18, “‘Contracting for Sex in the Pacific War’: The Case for Retraction on Grounds of Academic Misconduct” by Amy Stanley (Northwestern University), Hannah Shepherd (Yale University), Sayaka Chatani (National University of Singapore), David Ambaras (North Carolina State University), and Chelsea Szendi Schieder (Aoyama Gakuin University).

Exposing the paper’s lack of evidence and problematic research methods, the authors found that Ramseyer’s eight-page paper was riddled with historical inaccuracies, misrepresentations of sources, inaccurate references, missing citations, and unfounded claims. One of Ramseyer’s sources was a dubious anonymous blog active since 2016 entitled “Korea Institute of History” that contains selective and partial translations of survivor testimonies and blog posts promoting revisionist interpretations of comfort women history. Perhaps most damningly, Ramseyer cited no evidence of extant contracts to support his argument that comfort women were contracted prostitutes, a point that he himself has admitted in an interview and scholars such as Alexis Dudden of University of Connecticut and Andrew Gordon and Carter Eckert of Harvard University have pointed out violates “any reasonable standard of academic integrity.” It is unclear whether historians specializing in Japan served as peer reviewers for IRLE’s assessment of the article. Ensuing demands for accountability and for Ramseyer’s paper to be retracted from many academic corners caused as many ripples throughout the Twitterverse as had more public-facing news coverage. And so Ramseyer’s defenders came out in force.

Social Media and Japan’s Right Wing

Japan’s internet right wingers are known as netto uyoku ネット右翼, or neto uyo ネトウヨ for short. This term is treated in the media and right wing internet communities themselves as a derogatory one, evoking an indignant denial of ultranationalist identity from those who are its most conspicuous embodiments.2 Broadly speaking, neto uyo are a loosely connected network of individuals on social media (especially Twitter) with a few key instigators. They toe a familiar ultranationalist line of xenophobic and discriminatory views. On social media they fill their bios with combinations of jingoistic and discriminatory phrases, from “I love Japan! PATRIOTISM!” “Protect Japan! No communists!” and “Amend the Japanese Constitution!” to “I hate anti-Japanese countries!” (that is, China, South Korea, and North Korea) and “I despise the anti-Japanese trash mass media!” Some profile pictures and headers proudly feature the Japanese wartime flag, which they vehemently deny is a symbol of imperial oppression, or a particular photo of scowling Donald Trump, publicly performing their solidarity with his views. “Fake news” and rabid anti-leftist rhetoric, particularly on social media, has intensified across the globe; since 2017, even QAnon has found a place in Japan, integrating easily into preexisting far right communities.

| Typical Twitter bio of a neto uyo. Translation: “I’m Japanese, so it is only natural that I love Japan. Yamaguchi Prefecture is the best! I pay my respects to the many great patriots from Yamaguchi. I am from Fukuoka Prefecture. I am conservative. I hate anybody who is ‘anti-Japanese’. Pleased to meet you.” |

The neto uyo’s reaction to the “Case for Retraction,” the New Yorker article, and other critiques showcased their routine tactics. They began repeatedly dropping links to far right blogs, news sites, and Youtube channels on the tweets of their critics and in the replies of others who expressed support for them, stating that we needed to study the “correct” materials to have the full story, a story which confirmed Ramseyer’s historical claims. The neto uyo alleged that foreign scholars were attacking the Japanese while conveniently ignoring war crimes committed by their own countries. A slew of ultranationalist comfort women truthers followed, with an army of logical fallacies and racist talking points that were equal parts anti-Korean outrage and nativist assertions that only they had the facts. “Do you discriminate against Japanese people?” one wrote. “If not, take a look at this,” linking to a right wing propaganda video by a well-known comfort women denier.

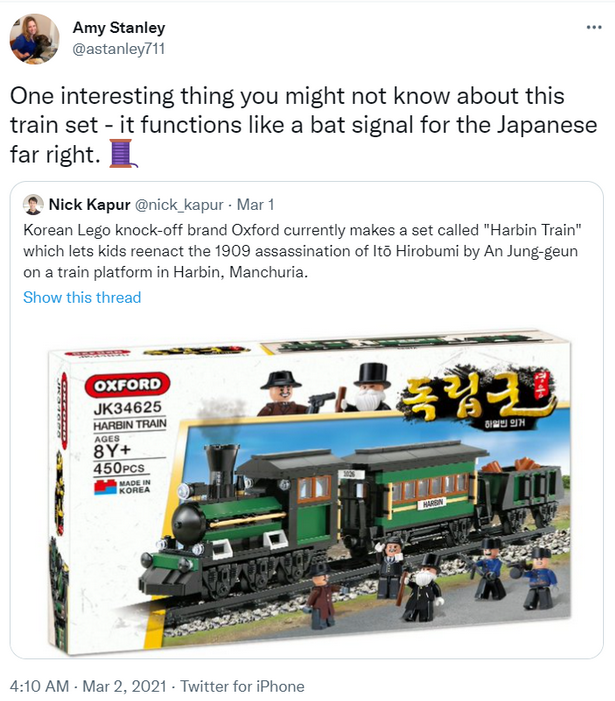

The Japanese right wing commonly use these all-or-nothing and whataboutist approaches in online harassment to paint overseas critics as anti-Japanese (hannichi 反日) and summarily dismiss their perspectives. Once several of us were on the radar of key leaders in the neto uyo Twitter community, who boast tens of thousands (and even hundreds of thousands) of followers, they took to visiting our accounts and leaving comments on any and every tweet they found, frequently revisiting old ones and retweeting them to ensure our perceived offenses stayed in circulation. One of their favorite methods to incite commentary was to leave an image of an Oxford Co. brick toy set depicting the 1909 assassination of Prime Minister Itō Hirobumi on our threads, asking “What do you think about this?” with the hope that we would respond with condemnations of Korea or affirmations of our purported anti-Japanese leanings.

In the weeks that followed, those who became targets of these right wing circles experienced a wide variety of online harassment as the neto uyo dug through our online media profiles and professional pages (screencapping and sharing them), tweeted at our employers and funders calling us racists spreading hate speech, and gleefully declared that anyone who blocked them was no scholar, as we “ran away” instead of engaging in discussion. Some of us received hate mail, some of us death threats. The worst of the harassment was reserved for female researchers, whose credentials were relentlessly questioned, as well as native Japanese scholars, who received comments questioning their ethnicity. Those residing in Japan endured particularly virulent attacks on their personal lives and places of employment.

Information about our backgrounds was quickly integrated into the conspiracy theories that motivate many neto uyo. One ringleader used past funding information—a Japan Foundation grant from 2015—to incite her followers to attack me, stating “This person is receiving a scholarship from the Japan Foundation. In other words, she’s doing Japan research using Japanese taxes and spreading hate of Japan all over the world. Let’s do something!” Some accused us of being funded by South Korea or China, saying that Korea “spent money on Amy Stanley, BTS, and anti-Japanese activities” and the authors of the refutation were “in cahoots” with South Korea. We were also “in a coterie of communist scholars,” and some of the tweets promoted by the neto uyo leaders (from accounts now suspended) even claimed that Jews were secretly running the Japan Foundation. This anti-Semitic rhetoric is a complementary thread running through various accusations, including that scholars disagreeing with Ramseyer are communist collaborators. One harasser wrote: “A.Stan is a member of the Society of Fake Historians that spread anti-Japan lies/propaganda collaborating with Richard [Painter], North Korea, and CCP because Japan saved Jews in WW2. Two kinds of Jews exist. One are the good Jews who were sacrificed in Germany by the other kind of Jews,” adding to their thread “The latter are really evil. A.Stan and her companions belong to them. She is absolutely a racist who seems proud of that her type of Jews is the No.1 race. Evil type of Jews has long been collaborating with CCP because they are most dominant in global financial capitals.” Any attempts to actually engage with the less extreme neto uyo using facts or reason were immediately met with deflections, purposeful misinterpretations, and inevitably illogical and potentially racist attacks. Many of us quickly learned the best methods to mass-block on Twitter in self-defense.

It has now been over eight-months since the initiation of this harassment, many of us are still being targeted by the neto uyo. Our tweets are being monitored from alternative and anonymous accounts, linked and screencapped on Twitter, and circulated on conspiracy blogs and web forums. Even if we do not directly engage, we may find, as in my case, that screencaps of statements from as much as five months prior are repeatedly retweeted and even turned into pinned tweets at the top of ringleaders’ feeds to ensure their followers see their cause as under constant attack. This form of relentless online provocation is so commonplace among digital extremist communities in Japan that it has even been given its own term: resuba レスバ, an abbreviated combination of the words “response” and “battle.” One who engages in a “response battle” makes empty, meaningless replies over and over again in lieu of an actual analysis.

To combat the neto uyo insistence that overseas scholars were in fact harassing them (a common complaint), I catalogued approximately eight months of tweets from one neto uyo ringleader’s account, finding that in some 249 days she had tweeted directly at or about me and the five writers of the Ramseyer refutation approximately 985 times. By now, it has surely far exceeded that. This is a staggering number for a single person. On May 6, 2021 alone she tweeted about Amy Stanley 62 times. If these numbers were applied to telephone calls or knocks on one’s door, scholars and administrators would no doubt take them far more seriously as disturbing behavior that requires dedicated attention. Yet, many still take social media quite lightly.

Academics and the Public Sphere

During these months of harassment, J. Mark Ramseyer hung over the online discourse around comfort women and the ownership of history like a specter, always there, but curiously absent in the flesh. For weeks after the criticisms and news media coverage circulated, he remained silent and made no formal or public statements on his work. Yet, the neto uyo vehemently defended every word of it. They tweeted and screencapped and churned out bilingual hashtags like #ProtectJohnMarkRamseyer / #ラムザイヤ教授を守れ and #ラムザイヤー教授の慰安婦論文は覆せない (Professor Ramseyer’s comfort women article cannot be overturned). They angrily complained that the “anti-Japanese scholars” were not providing evidence that Ramseyer was wrong, though they entirely refused to engage with the 36-page refutation, several other critiques, or any historical documentation provided. In their eyes, Ramseyer had reached the status of savior and defender, a right wing champion whose Harvard credentials and Order of the Rising Sun award were beyond reproach.

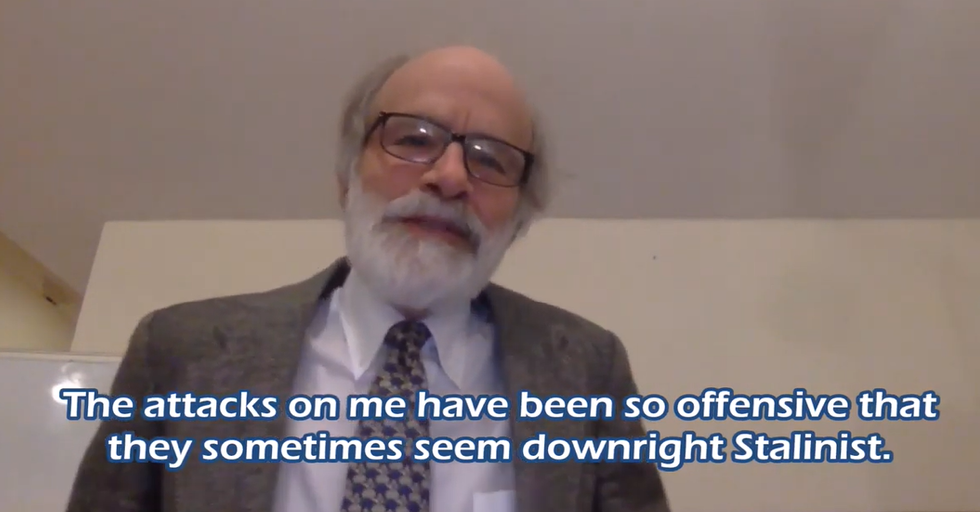

Ramseyer finally appeared during late April 2021 as part of a video conference, the “Emergency Symposium on the International Historical Controversy over Professor Ramseyer’s Article,” organized by the International Research Institute of Controversial Histories (国際歴史論戦研究所 Kokusai rekishironsen kenkyūsho). In his message delivered in Japanese to the symposium attendees he stated that they faced two challenges: “recounting the events of the past accurately, specifically, thoroughly, and in an unbiased manner to the extent possible” and “the protection of academic freedom at all costs.” At the same time, he claimed that one of his motivations for writing his article was that the majority of English-language materials on comfort women were “marred by Korean anti-Japanese bias,” which he claimed was particularly true among American academics. Framing the entire issue around a need for academic freedom (instead of “political correctness”), Ramseyer asserted that his critics wanted all scholars to think alike, and that the “attacks on [him] have been so offensive that they sometimes seem downright Stalinist.” Decrying his critics as all young assistant professors, he said they took pride in “acting like scholar-assassins” (学者として暗殺未遂みたいな行為をとって gakusha to shite ansatsu misui mitai na koi wo totte) towards him and disregarding academic freedom.

A screenshot of Ramseyer speaking in the video conference

(From a recording published on YouTube)

Ramseyer’s comments play directly into the right wing’s rejection of scholarship that does not affirm their views, painting himself as a victim of oppressive academic institutions where young upstarts push political propaganda and engage in character assassination of those they disagree with. His comments and presence serve to fill a crucial gap that has previously prevented the historical denialist community from obtaining the legitimacy they seek within and outside Japan.

Yet, as Suk Gersen has pointed out in an interview for the Harvard Asia Center, multiple individuals and groups, including the five scholars who fact-checked Ramseyer’s statements and sources and even his colleagues at Harvard, Andrew Gordon and Carter Eckhart, independently concluded that Ramseyer lacked data—in this case, actual contracts—to back up his claims. Suk Gersen clarified “I don’t conclude and I don’t think historians conclude that there couldn’t have been contracts, it’s really more [that]… if you are going to say what the contracts consist of, there should be some basis for it.” Despite Ramseyer’s declaration that events must be recounted with accuracy and specificity, his article offered no counterevidence to or engagement with the vast body of historical scholarship on comfort women while cherry picking from testimonies that in many cases, as Suk Gersen notes, “were cited in a way that was plainly contrary to what the source actually said.” These instances embody the “Ivory Tower” at its worst, the kind of academia that scholars have been struggling uphill to reform and decolonize. If anything, this incident has shown that the veneer of legitimacy afforded by privilege can have devastating effects, effects which cannot and should not be ignored.

Around the same time that Ramseyer participated in this event, I guest lectured via Zoom in a colleague’s modern Japanese history class, recounting the Ramseyer affair from its beginnings to the online furor that has continued to haunt myself and my colleagues. “But why do you do it?” the students wanted to know when I told them that many of us still engaged with the worst (and sometimes, the most absurd) of our trolls. I told them that we felt a responsibility to stand our ground and be advocates for academic integrity and the damaging effects of misinformation. Another student added, “But how could a Harvard professor do this?”

This question struck at the heart of what many online and elsewhere have been asking from the beginning: Why was this allowed to happen? Though there is no single, satisfying answer, for those with experience in academia this is not a question that needs to be asked. Time and time again we have seen that privilege, institutions, and networks of enablers allow certain people, (most often senior, white men at elite schools) to abuse their positions. In this case, the author embodied numerous intersections of privilege: a senior, white, male scholar employed at an Ivy League institution through a professorship endowed by a prominent Japanese company whose work has also been recognized by the Japanese government with one of its highest awards, the Order of the Rising Sun. Yet, if we are indeed to protect the right of academic freedom, then the tenets of academic integrity must apply to all of us.

The stakes of history may not always seem high when one thinks of the past as something distant that has no impact on today’s world—something that one learns about in textbooks, in the context of the classroom. In this sense, history does not necessarily feel “present.” But these pasts were once and are still a part of people’s lives. It is essential that historians and other academics communicate how and why academic misconduct has real world consequences. To step in, rather than stand by.

Does it matter that we hold public-facing history accountable for academic integrity? The neto uyo felt victorious and vindicated to see that a Harvard professor sided with their extremist views (however they chose to interpret them), and the validation of these beliefs can quickly translate into real world violence. Consider how plans to publicly discuss the “comfort women” triggered threats to burn down the 2019 Aichi Triennale featuring Kim Seo-kyung and Kim Eun-sung’s Statue of Peace. When some of the same works featured at the Triennale were exhibited in Osaka this summer, they were met with protests and a threatening package purporting to be the nerve agent sarin. We are beyond believing that what is written in the pages of academic journals—now more accessible than ever through online media—will not make it to a public audience, particularly when the authors are prepared to translate their studies into easily digestible pieces for news outlets.

Does it matter that we combat a false history of contracts legitimizing the sexual enslavement of women some 75 years ago? Consider the Nagoya man who was arrested this past June for forcing a 13-year old girl into signing a “slave contract” before raping her. We cannot know what motivated the perpetrator to take this step, but the rhyme of history is evident throughout this incident; all manner of atrocities have been done using a shield of legality. Here we find an undeniable resonance with the history of comfort women as sex slaves, justifying the trafficking of women and girls through the supposed validity of contracts while ignoring the question of coercion.

Does it matter that academics hold peer reviewed venues and media venues alike accountable to experts for their content? Consider that on August 29, 2021, the extreme right wing LDP Diet Member Mio Sugita suggested in her official capacity that the diplomatic budget include the promotion of “correct histories” like that of J. Mark Ramseyer, while one of her colleagues stated that there should be an official way to monitor overseas activities that “defame” Japan. This recommendation was posted to her blog and tweeted to her 232,000 followers, gaining widespread visibility among neto uyo communities and, in their eyes, further legitimizing their position that any criticism of Japan (current or historical) amounts to anti-Japanese activities that must be surveilled and quashed. Although the scholars who refuted Ramseyer’s article did so with academic rigor and extensive documentation, many ultraconservative Japanese netizens and academics alike argue that they are denying Ramseyer’s right to academic freedom—an ironic stance in light of the suggestion that anti-Japanese activities be monitored and “correct histories” promoted by the Japanese government. Although the original 36-page refutation provides a model of academic integrity, almost a year later, IRLE has not retracted the paper. Ramseyer has not responded in English to any criticisms of his work.

Beyond the Tower

Despite vigorous challenges to liberal arts education in recent decades, social media has proven that the skills taught there are more valuable than ever; critically evaluating sources of information, identifying bias, and ethically employing history are far from irrelevant. Hundreds of analog and digital pages have been written as a result of Ramseyer’s eight-page article. The professional, mental, and emotional labor spent has been enormous. The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus released two special issues of articles in response, one on comfort women and the other on Ramseyer’s recent burakumin studies. Even scholars outside the history field have been critical of Ramseyer’s approaches for years, though it is only recently that his radicalization has become more visible; he has even gone so far as to openly admit that by focusing on Koreans, Burakumin, and Okinawans in his work, he can “avoid the well-known ethnic disputes in the U.S. and elsewhere,” as “the hyper-polarization within the academy has made candid discussion of ethnic politics extraordinarily hard.”3 That is, avoid using examples that would undoubtedly invite harsh criticism. In response to these numerous problematic claims, prominent scholars such as Tessa Morris-Suzuki and even student groups such as Stand with “Comfort Women” at Yale University, have now created study aids and resource guides to put these issues in perspective in the classroom and beyond.

Among the consequences of the debates over the Ramseyer affair is the fact that the Asian Studies field is invigorated to combat historical misrepresentations and their defenders on and offline. Although social media has sometimes provided a platform where history is corrupted, twisted, and misrepresented, it has also generated new possibilities for solidarity among those who would step up to challenge the misuse of the past and refuse to let malignant untruths proliferate without accountability.

The Ivory Tower’s walls are beginning to crack–not merely because our academic institutions and freedoms have been and still are under serious threat, but because those who have abused their positions of influence by leveraging distinguished titles and elite affiliations are finding that virtual connections are beginning to erode barriers of privilege. For better or for worse, the age of social media has seen accountability arise at a speed and scale like never before. Academics have been told for decades that they must leave their towers and speak to the common person. They have been told that they must step up and be present, accessible, responsive, and relevant.

There are undoubtedly many ways that academics can fulfill that mission, but the demands that we be public, particularly on social media and in the popular press, continue to grow. And for all the benefits of closing the gap between the academic and public spheres, we must wrestle not only with the standards of academic integrity in our peer reviewed mediums but also with the dangers of how information is misused and weaponized in digital spaces. The effects of misinformation and disinformation can be far-reaching and immediate, when an eight-page article and a 1,500-word news blogpost can generate an international incident with global ramifications. Whether we like it or not, the fight for history is taking place on a digital battleground. Now, more than ever, it is imperative that we rise to meet our duty as public intellectuals, dispense with towers, and serve the public by countering outrageous narratives that do injustice to the past and to those who lived it. You asked for us. Here we are.

Notes

For an examination of the intersection of neto uyo, politics, and their relationship to formal and popular media outlets, see Ogasawara, Midori. “The Daily Us (vs. Them) from Online to Offline: Japan’s Media Manipulation and Cultural Transcoding of Collective Memories.” Journal of Contemporary Eastern Asia 18, no. 2 (December 30, 2019): 49–67. doi:10.17477/JCEA.2019.18.2.049.

J. Mark Ramseyer, “A Monitoring Theory of the Underclass: With Examples from Outcastes, Koreans, and Okinawans in Japan,” (January 24, 2019), 2.