Abstract: Japan’s scrappy weekly magazines, led by Shukan Bunshun, are filling the void in investigative journalism left by the mainstream media. The editor of Shukan Bunshun, Shintani Manabu, says the magazine’s combative reporting is driven by commercial not ideological concerns – and its bigger rivals must learn this lesson, or risk irrelevance.

Keywords: Media, Shintani Manabu, Olympics, Suga Yoshihide.

Among the more mortifying titbits to emerge from a rich banquet of Tokyo Olympic scandals in 2021 was the proposal that a plus-sized Japanese actress descend from the sky during the opening ceremony dressed as a pig. Sasaki Hiroshi, creative director of the ceremony, thought this would be a gas, dubbing his idea “Olympig.”

It’s unlikely that story from March – with its jaw-dropping blend of tin-eared sexism and creative constipation – would have seen daylight were it not for Shukan Bunshun. The weekly magazine culled its scoop from leaked Olympic documents, then coolly shrugged off a legal demand by the Olympic authorities that it pulp the story and delete all online versions.

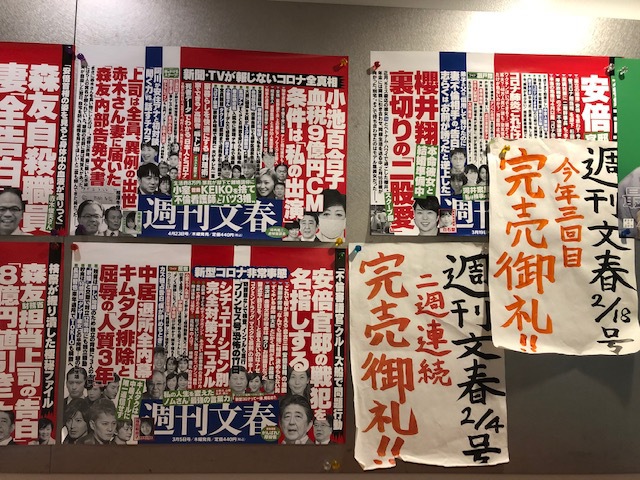

Under former chief editor (now executive director) Shintani Manabu, Bunshun is the closest Japan has to the confrontational tabloid reporting that mercilessly hounds British politicians and celebrities. The magazine’s journalistic firsts have made it a must-read every Wednesday, when it fires the latest online salvo from what has become known as the 文春砲 – the Bunshun howitzer.

Bunshun spent “months” chasing the scoop, recalls Shintani. “This work is expensive, and risky,” he noted during an interview at his office.

That makes Bunshun’s hit-rate all the more striking. It is a relative publishing minnow, with a weekly print-run of 500,000 copies (of which about 300,000 typically sell), and a staff of just 30-40 journalists. By contrast, The Asahi Shimbun, Japan’s liberal flagship newspaper, has over 2,000 journalists and daily sales of over six million. The conservative Yomiuri Shimbun has even greater resources.

The engine beneath the hood of this scoop-machine is Bunshun leaks, a service that brings in dozens of story tips a day from the public. As the magazine’s reputation has grown, many sources opt to tip off its editors rather than mainstream media outlets, politicians or even the police, out of fear that they will suppress or water down the story.

Bunshun’s political scalps last year included Kurokawa Hiromu, the head of the Tokyo High Public Prosecutors Office. The magazine revealed that Kurokawa had played mahjong for cash with two reporters from The Sankei Shimbun and an ex-reporter from The Asahi Shimbun – while the rest of the city’s population endured an emergency lockdown. The revelation ended Kurokawa’s career.

It also shed uncomfortable light on the access journalism practiced by Bunshun’s bigger rivals: the Asahi employee had once been in charge of covering the prosecutor beat. Neither the Asahi nor the Sankei, from opposite ends of the political spectrum, saw fit to tell their readers that Kurokawa, a powerful and controversial government figure, was breaking the curfew. Shintani says the result is declining trust in the media.

“That’s a good reporter, from my point of view…he played mahjong for about five hours with Mr. Kurokawa. The problem is not publishing an article afterwards. If he was my reporter, of course I would allow him to go – but the following week Bunshun would carry the story: “Exclusive confession of Attorney General Kurokawa over five hours of mahjong.”

“I would have asked him questions such as ‘Do you really want to be prosecutor general?’ ‘Isn’t it inappropriate to extend your retirement age?’ That’s how you do it.”

Kurokawa was politically connected and was widely seen as the government’s choice for Japan’s top prosecutor. He had been in the news for months since January when he was controversially allowed to remain in his post despite exceeding the mandatory retirement age.

Of course, Kurokawa may never speak to the reporter again, Shintani accepts. “But our job is not to maintain relationships, it’s to convey the facts to as many people as possible. It is important for everyone to be prepared to reveal what they have to reveal, even if it means wrecking human relationships…You can’t stop because you’re on good terms (with a politician). You can eat sushi with Prime Minister Abe, or eat pancakes with Prime Minister Suga. If you get along well, listen, and find out the truth even if it is inconvenient, and then write it up without mercy.”

Pancake Breakfasts

The pancakes are a reference to Suga’s breakfasts with reporters, including one last year where he briefed off-the-record on the government’s decision to reject six nominees to the Science Council of Japan, reportedly as payback for their criticism of his predecessor, Abe Shinzo. Off-the-record briefings, when they result in the withholding of key information (as watchdog Poynter notes) corrode trust in the media at a time when such trust is already low.

Suga and his handlers are not above more sharp-elbowed tactics. Bunshun speculated in 2020 on the removal of Arima Yoshio from his role as anchor of News Watch 9, the flagship evening news program on NHK, Japan’s powerful public broadcaster. During a live interview in October, Arima had asked Suga to elaborate on why he had blocked the appointment of six scholars as advisors on government policy.

“I think there are people who want an explanation about what it going on,” prodded Arima. Observers noted that the atmosphere in the studio cooled as Suga treated Arima to his trademark hooded glare. “There are things that can be explained and things that cannot,” he said, cutting him off. Afterwards, Suga’s handlers allegedly bore down on NHK for asking an unscripted question.

The interview, and its denouement, may sound familiar. In 2014 Kuniya Hiroko, who had anchored NHK’s investigative program, “Close-up Gendai” for two decades, was also removed following an uncomfortable encounter with Suga. The weekly press then, too, blamed Kuniya’s downfall on an interview during which she asked the then chief cabinet secretary an impromptu question on the possibility that new security legislation might mean Japan becoming embroiled in other countries’ wars.

In both cases, critics responded by explaining that NHK anchors are routinely rotated to other bureaus – and Kuniya, who had powerful sponsorship inside NHK – was well overdue for a move. Of course, the rotation system is in itself designed to make sure nobody becomes too big for their journalistic boots. Arima’s predecessor on News Watch 9, Okoshi Kensuke, was also allegedly ousted after a clash with a member of the Abe government.

The near simultaneous departure in 2016 of Kuniya and two other liberal TV anchors from the commercial airwaves, Ichiro Furutachi of TV Asahi’s “Hodo Station” and Shigetada Kishii of TBS (all comparatively robust critics of the government) sparked a major political row and drew global attention on the Abe government’s attempts to cajole and coerce the media. Expectations that Suga might improve relations with the press corps were low, therefore, when he succeeded Abe in 2020. If anything, he was worse than predicted, laments Hayashi Kaori, a media scholar at the University of Tokyo. “I think the situation has exacerbated under Suga,” she says. “Abe was talkative but Suga just tries to avoid questions and manage what is said. He has no opinions at all.”

These qualities were laid bare during Suga’s press conferences on the coronavirus pandemic, which often seem closer to stenography than journalism. His non-answers and repeated use of the phrase “I would like to refrain from responding” became a mocking internet meme. Observers note his apparent nervousness at the lectern, and how be clams up or lashes out (‘Your point is irrelevant’) when pressed to explain what the government is up to.

“The prime minister seems to believe that the role of press conferences is to unilaterally convey the government’s oven-ready thoughts,” says Hibino Toshiaki, a reporter with the Kyoto Shimbun newspaper and member of the Kantei (Prime Minister’s Office) press club. “So new facts are rarely unearthed at these press conferences.” To insulate himself from the growing flak about his pandemic response, Suga sticks to prepared texts and carefully stage-manages his meetings with journalists.

Trusted reporters from the elite media are assigned by Kantei bureaucrats. In most cases, says Teddy Jimbo, founder and CEO of Internet broadcaster Video News Network, Suga is literally reading his replies from a script. Jimbo was one of the few reporters to ask a free question, at a live televised press conference in January 2021. “I said, ‘All night you have you been asking us what we are prepared to sacrifice. My question is, what has the government been doing while asking for sacrifices. Japan has the largest number of hospital beds in the world, so why is our medical situation in an emergency?’”

The query, and the suggestion that the government was not doing enough to push the Japan Medical Association to convert more hospital beds to emergency use, seemed to throw Suga, recalls Jimbo. “He was looking at me very nervously and simply said, ‘I’ll look into it.’ I don’t think he understood the issue.”

Press-club management is hardly a new topic in Japan. But the clubs’ role in stage-managing news has become starker as the ranks of freelancers and Internet journalists grow. The only reason Jimbo got to ask the question at all, he speculates, is because the new Kantei press manager may not have known who he was: Jimbo reckons he got to ask just two questions in the seven-and-a-half years of Abe’s tenure. “It’s not a free press if it is all pre-arranged. But that’s how it works: the bureaucrats are in control of 99 percent of what happens in Japanese politics.”

Suga earned his political spurs as Prime Minister Abe’s loyal enforcer during his record stint as the government’s top spokesman. His tenure was marked by terse encounters with reporters, and a renewed government focus on bastions of perceived liberal journalism, particularly in The Asahi Shimbun and NHK. One of the prime minister’s first moves was to appoint four conservative allies to NHK’s board. Momii Katsuto, the corporation’s new president, had no broadcasting experience and quickly asserted that NHK’s role was to reflect government policy in a now notorious formulation ‘when the government is saying right, we cannot say left’.

The governing Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) wrote to television bosses in 2014 demanding political impartiality. In 2016, the communications minister, Sanae Takaichi, threatened to close television stations that flouted rules on impartiality. There were skirmishes with reporters deemed “anti-government” and access granted to favored scribes.

Those who stepped out of line, such as Mochizuki Isoko, the spry Tokyo Shimbun reporter who became Suga’s nemesis during daily government briefings, were slapped down. In December 2018, for example, Mochizuki repeatedly questioned Suga on land-reclamation work in Henoko, Okinawa, where the government is building an offshore American airbase, mostly in defiance (as Mochizuki pointed out) of local wishes.

Mochizuki was harried throughout by the press-club moderator to wind up her question. Suga grew increasingly irritated before shutting his briefing book and snapping back: “this is not the place for responding to your assumption” and stalked out of the room. The encounter between a dogged journalist determined to probe authority and a government accused of authoritarianism had a mythic quality that has appeals to some. Mochizuki was the subject of a 2019 documentary by acclaimed filmmaker Mori Tatsuya.

The LDP’s distrust of the media has deep roots. In 1993, amid economic stagnation and corruption scandals, the party was drummed out of office for the first time since 1955. Party strategists concluded that they had underestimated television and the influence of a new breed of unconventional anchors, particularly Kume Hiroshi of TV Asahi’s News Station. TV Asahi’s director of news Tsubaki Sadayoshi seemed to confirm this when he rashly boasted of his network’s power to swing public opinion against the government. For those who argued that the Japanese media was guilty of liberal bias, the Tsubaki incident was something of a smoking gun. Tsubaki told a meeting responding to a summons for testimony before the Diet that TV Asahi had enough clout to swing the election against the LDP. “Shouldn’t we cover it in such a way as to prevent the continuation of the LDP government, and to help establish a non-LDP coalition administration?” he said. “I organized the coverage with that thought in mind, without discussing it with the political news desk or with the programming directors.”

The consequences of the Tsubaki Incident rippled far into the future and demonstrated the ability of LDP elders to learn political lessons—and nourish a grudge against the liberal media, Asahi in particular.

Bunshun’s attempts to circumvent the government’s media management are driven partly by commercial demands – unlike newspapers, it does not have a captive subscription-based readership. The mass-circulation weekly press has no access (except via tips) to the press clubs. While the clubs are regular targets of criticism, the weeklies and online media “have challenged the daily papers’ dominance of political news in recent years”, noted Freedom House, a watchdog, in 2017.

During the Fukushima crisis of 2011, for example, while the big media endured taunts of happyo hodo (press-release journalism) because of its perceived collusion with the nuclear establishment, Shukan Shincho, Bunshun’s key weekly rival, angrily dubbed the management of Tokyo Electric Power Co (Tepco), the plant operator, senpan (war criminals). Shukan Gendai, another weekly, outed the most culpable of Japan’s elite pro-nuclear scientists, calling them goyo gakusha, (government lackeys).

In 2017, Shukan Shincho published rape allegations against Shinzo Abe’s biographer, Noriyuki Yamaguchi by journalist Shiori Ito. The story included the eleventh-hour suspension of Yamaguchi’s arrest warrant at Narita International Airport allegedly by Itaru Nakamura, a former political secretary to Suga. Arguably, Bunshun’s successes have egged on its rival Shukan Shincho, which has also revealed multiple political scandals.

In 2021, the weeklies revealed that an NHK Special on the Olympic Games, due to be aired on January 24, was abruptly cancelled. Insiders at the corporation said senior producers grew nervous about the content, which would have asked experts why the Games were going ahead in the middle of a pandemic – and who benefitted.

Bunshun leads the weekly pack. In January 2016, it speared economy minister Amari Akira over bribery claims, forcing him to quit. Shintani says his source went first to The Yomiuri Shimbun – Japan’s largest-circulation newspaper. “He told the story to a reporter from the paper’s social affairs division but the reporter didn’t seem interested and left without paying for his coffee. I don’t know how long it took but he finally came to us.”

Shintani says Bunshun’s “guerrilla journalism” has clear advantages in such cases. “We’re small but people trust us and feed us stories,” he says. Bunshun has far fewer organizational hurdles to clear than NHK or The Yomiuri, where editors can spike a potentially risky story at any point up the chain of command. “We are not in the press clubs but we have access to all kinds of information gathered from our Bunshun leaks source.”

“Reporters for the big media are salarymen,” he continues. “If they knew it was a scoop they’d go after it but they don’t get it. It’s like having muscles you don’t use – when they atrophy, they’re useless. I’m asked all the time why we get scoops. The simplest way to answer that is that we seriously go looking for them. We have to.”

Ideology over Journalism

Last year, Bunshun disinterred one of the most notorious scandals of Abe’s tenure when it published a suicide letter by Akagi Toshio, an official who had been ordered to falsify Finance Ministry documents, apparently to protect Abe and his wife. The so-called Moritomo scandal erupted in 2017 when the firm that ran Moritomo Gakuen, an ultra-nationalist kindergarten, bought a plot of public land in Osaka City for about 14 percent of its value and began building a primary school to propagate rightwing ideas.

Opposition politicians suspected a sweetheart deal backed by nationalist politicians sympathetic to the school’s curriculum. The school invoked the name of Prime Minister Abe when soliciting donations. Abe’s wife, Akie, gave a speech at the kindergarten and was named honorary head teacher. The prime minister had previously praised the school’s owner, saying that they shared a “similar ideology”. Abe Akie’s name was later scrubbed from the kindergarten’s website.

Under fire in the Diet in February 2017, Abe denied any knowledge of the land sale and said he would quit if anyone proved he or his wife were involved. At that point Akagi Toshio was called in by Sagawa Nobuhisa, the local bureau chief of the finance ministry, to alter the documents and hide the involvement of Abe Akie and other senior officials and politicians. An internal investigation by the Finance Ministry later concluded that Sagawa alone had ordered the cover-up. He and a handful of others were punished with paycuts and suspensions but nobody was held criminally responsible. Finance Minister Aso Taro has refused to order a third-party probe. Among the questions that linger was whether the decision of the regional bureau to remove descriptions in documents referring to Abe Akie was made by an official there, or did he receive instructions from the prime minister’s office? Bunshun also reported, in December 2018, that prosecutor Kurokawa had helped to halt an investigation into the affair.

Shintani has been praised by liberal commentators for keeping the story alive and “taking the fight to the Abe and Suga administrations” – (Suga announced he was stepping down in September 2021) but says that misses the point. “If you’re really serious about journalism right now, and if you’re thinking about keeping it alive, you’re talking about how you can make money because investigative journalism is extremely expensive. It’s not sustainable unless the article makes money.”

The American media during the Trump era made the same mistake, he says – ideology over journalism (which explains collapsing viewership at CNN). “If you report accurately and well, and people support and trust you they’ll buy your stories.” This point has become all the more acute, he says, as the circulation of the print media collapses: The number of daily newspapers sold every day in Japan has fallen by more than 16 million since peaking at nearly 54 million in 1997. Circulation of the mass weeklies is down to a quarter of its peak in 1995.

Bunshun has helped monetize the Internet by releasing its scoops on Wednesday, the day before the print edition goes on sale. Its biggest stories sell up to 40,000 copies at 300 yen each – plus income from advertising. “Getting money on the Internet means producing something you can only read there,” says Shintani. “It has got to be your own investigative journalism and your own scoop. Grasping that is the most important thing right now.”

As for the risks, that’s part of the job too. “I’ve been sued countless times. I’ve been subpoenaed to testify four or five times. It doesn’t make me happy but if you do this work it cannot be helped. We’re not being sued for telling lies.” In many cases, he says, politicians, their supporters, or political colleagues, will scream that a story is fake, threaten to sue, then quietly drop it a bit later. “Then we all go back to work.”

Thanks to Reika Shiratori and Chie Matsumoto who helped with the research and transcription for this article.