Abstract:This article examines the often-noted “cuteness” in early post-war Japanese animation, and explains how this style has led in more recent years to grittier works depicting war’s devastation through fantasy and cinematic technology. Anime provides insight into the social attitudes of each post-war era; and, into how collective memory has processed “unimaginable” horror. The author argues that what is concealed within “unrealistic” animation often reveals more than what is shown about people grappling with an apocalyptic legacy in search of a national identity.

Keywords: Anime, Manga, Hiroshima, Nagasaki, Nuclear, War, Tezuka, America, Women, Technology, Miyazaki, Apocalypse.

Introduction

In early August, 1945, “Little Boy” and “Fat Man” destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Fire-bombings had already devastated 64 major Japanese cities in the final months of the Pacific War. Two weeks later Japan entered a new era facing the dual challenges of massive destruction and foreign occupation. In the years that followed, the A-bomb came to be depicted in the arts. This trend emerged in such films as Shindo Kaneto’s Children of Hiroshima (1952), Imamura Shohei’s Black Rain (1989), and with the unnatural blooming of flowers in Alan Resnais’ Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959). Manga and anime began depicting the A-bomb in the 1950’s.

In this article, I will explore three recurring elements in A-bomb anime: (1) “cuteness,” (2) the role of female and child characters, and (3) apocalypse, fantasy and technology in more recent anime. I will explain how A-bomb anime reflected public opinion towards the Japanese government and the Allied Forces, and played a part in reinventing Japan’s global image post-war.

‘MADE IN JAPAN’ – Cuteness in Post-War Anime

A few years after The Bomb was dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, a seemingly incongruous trend began in Japanese animation – that of the increased popularisation of the “cute” in its productions. Paul Gravett suggests that animation became an integral medium through which Japan could express and explore its grief, guilt and confusion indirectly. He argues that this in turn allowed the people of a defeated nation a “transitory moment of dignity.1 The rise of cute characters in anime post-war allowed the country to process difficult realisations through a medium that “lives out – animates – questions and problems that are difficult, if not impossible to explore directly.”2

By contrast, Pauline Moore argues that the rise of cute figures during this period meant that they became intimately linked to images of apocalypse and suffering. In fact, she states that: “In the wake of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the comforting qualities of the cute figure are inextricably linked to the discomforting qualities of horror and grief associated with The Bomb”. These cute figures “offer comfort, and yet they continually deny such a possibility. Their eyes, moist and welcoming, are pools that mirror the nuclear explosion just as clearly as the camera flash.”3 In a way, this repeated use of cute characters in scenes of tragedy and disaster meant that the figures themselves became synonymous with apocalypse – a trait which became characteristic of this era of anime.

It is important to note that manga had a strong influence on anime and its depiction of cute characters.” During what Professor Masashi Ichiki calls the “golden years of the A-bomb manga” (1954-1973), one genre became especially prevalent in popular culture, the shōjo – or “little girl “ – manga, which comprised 39% of A-bomb manga. Shōjo manga on atomic and firebombing themes generally followed the same plotline: a romance unfolds between two young protagonists, who are ripped apart by some consequence of the bombing. For example, in Chieko Hosokawa’s Ai no Hitomi (Gaze of Love), a young couple fall in love and plan to wed only to find out that the young and beautiful female protagonist Yoko has contracted an unspecified disease related to radiation exposure. Such story lines on the direct effects of the bombings dominated shōjo manga of the 1950s-70s, which did not address the historical context of the attacks.

It is important to note that manga had a strong influence on anime and its depiction of cute characters.” During what Professor Masashi Ichiki calls the “golden years of the A-bomb manga”4 (1954-1973), one genre became especially prevalent in popular culture, the shōjo – or “little girl “ – manga, which comprised 39% of A-bomb manga.5 Shōjo manga on atomic and firebombing themes generally followed the same plotline: a romance unfolds between two young protagonists, who are ripped apart by some consequence of the bombing. For example, in Chieko Hosokawa’s Ai no Hitomi (Gaze of Love), a young couple fall in love and plan to wed only to find out that the young and beautiful female protagonist Yoko has contracted an unspecified disease related to radiation exposure. Such story lines on the direct effects of the bombings dominated shōjo manga of the 1950s-70s, which did not address the historical context of the attacks.

Such romanticized depictions began to appear in anime through the development of a brand of animation that Pauline Moore characterises as “hypercute”.6 Moore identifies three distinct generations of cuteness in post-war anime: “cute”, “hypercute” and “acute”.7

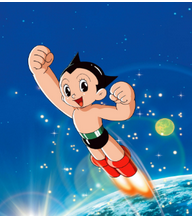

Here, I will focus on the two latter categories of animation, as they most accurately reflect the post-war climate in Japan. Perhaps the most prominent example of hypercute animation is the “God of Manga” Osamu Tezuka’s Astro Boy (originally Mighty Atom in Japan). This character is a particularly apt example of cute animation with his large round eyes and childishly innocence expression (see fig. 1).Originally a manga series beginning in 1952, Astro Boy became a televised anime series running from 1963 until 1966. It told the story of a young atomic-powered robot in a futuristic world where robots and humans co-exist.

Astro Boy is notable for forging a symbiotic relationship between American and Japanese animation – particularly Disney’s productions. The influence Disney is clearly seen in the work of Tezuka, who adapted Disney’s Bambi (1942) and The Jungle Book (1967) for Japanese anime and manga. Tezuka expressed his admiration for Disney, famously saying that he had “seen Snow White 50 times and Bambi 80 times”8 . . .

“Around 1945, daily life might have been hard, but the reputation of Disney was at its highest. […] It really was like the brightness of a rising sun”.9 Tezuka acknowledged the influence of American animation on his creation of Astro Boy, citing The Fleisher Brother’s Superman and Paul Terry’s Mighty Mouse. He stated in an interview translated by Schodt that “Atom’s father was in effect Mighty Mouse, whose father was Superman”.10

According to Moore, anime left the “hypercute” era of Tezuka, and entered the more contemporary “acute” generation with such works as Akira, Neon Genesis Evangelion, Ghost in the Shell (1995) and Appleseed. She describes these works as products of the “technological landscapes of death, destruction and danger”11 like their predecessors, but as choosing to “fight back” becoming much more malign in nature. It is in this generation that we truly start to see the emergence of apocalyptic themes in the stereotypically “innocent” medium of animation. Moore writes that these works are far more self-aware, and more directly address the topic of The Bomb. She suggests that, as opposed to the “utopian innocence” of the earlier “cute” anime, “the acute figure of contemporary anime shows itself as at once utopian and dystopian; and it fights back in the name of’ a lost utopianism and innocence.”12 Perhaps at its most basic level, what separates the characters of acute anime from those of the earlier hypercute anime is that they are no longer children, but have instead progressed into adolescence.

Although these characters have progressed beyond childhood, they are perpetually suspended in a teenage state between childhood and adulthood. The characters of acute anime have not yet lost their roundness and cuteness completely, but have become more adult and more realistic. As they have grown up, mistrust of their elders and authority figures becomes prevalent. This can be seen to represent the publicly expressed anti-militaristic sentiment which spread after their government’s willingness to sign the U.S-Japan Security Treaty permitting U.S forces and bases in Japan. As Matake Kamiya argues: ‘After witnessing nearly two decades of the follies of their own military leaders, the Japanese people developed a deep distrust of the military after the war, as well as a strong aversion to anything related to the military as a tool of national policy, including even Japan’s national security policy’13.

Another important development in acute anime was its representation of science and technology as a power to be simultaneously feared and revered in contemporary Japan. While the earlier hypercute animation, such as Astro Boy, served to popularise science, films such as Akira showed the dangers posed by its recent advances. Traditional Japanese anime emphasizes the sacrosanct force of nature with its inherent dangers. Contemporary anime elevates science to the status of the super-natural. This is most noticeable in Hayao Miyazaki’s immensely popular works, such as Princess Mononoke (1997) and My Neighbour Totoro (1988), which have led to his characterization as “The Disney of Japanese Animation” and “the Kurosawa of animation”.14 Acute anime presents technology as something beyond the force of nature, as awesome with a terrifying potential. In such films as Princess Mononoke technology posed against the “resilient powers of nature in the face of human lunacy and destructiveness.”15 As Moore puts it, contemporary animators have abandoned the “velvet glove” of Tezuka and other animators from the cute era and replaced it with the “iron fist” of technology, which is more in tune with contemporary consumer culture.

The phenomenon of cuteness in Japanese animation is complex in that it expresses both an escape from, and a reminder of, the devastation caused by The Bomb. It can be viewed chronologically as representing a timeline for Japanese attitudes toward the military and nuclear weaponry.

Moore writes that “Japan’s cute figure has lived through, and risen from, the ashes of The Bomb. Through this figure, there has been an attempt to speak the unspeakable, bridge the abyssal and defuse the fatal.”16 Acute anime functions to remind a nation of past devastation through dystopian imagery, and to emphasise the dangers of ignoring it while offering a form of comfort and escapism.

With the escapist aspect of anime, “scenes that even with contemporary special effects and contemporary values would be difficult to present and watch in live-action film became, in the non-realistic space of animation, enduring evocations of a genuine hell on earth.”17 This psychological buffer was then reinforced further by the unrealistic imagery of cute characters, which helped post-war anime become the perfect medium through which representations of nuclear weapons could be expressed.

“Pathetic Symbols” – Women and Children in anime

Along with cuteness in post-war anime, the role of women and children was a prominent feature. As noted above, anime protagonists rarely progress beyond adolescence, and generally adult characters generally function in the roles of parents and authority figures. However, a strong bond is consistently portrayed between mother and child. The importance of this role can be viewed in the context of “amae”, a term referring to the almost sacred bond between a mother and child in Japan. According to psychoanalyst Takeo Doi: “The psychological prototype of ‘amae’ lies in the psychology of the infant in its relationship to its mother; not a new-born infant, but an infant who has already realised that its mother exists independently of itself … [A]s its mind develops it gradually realises that itself and its mother are independent existences, and comes to feel the mother as something indispensable to itself, it is the craving for close contact thus developed that constitutes, one might say, amae.”18 In an oft-cited example of the mother’s importance, even Japanese soldiers during WWII, “trained to go to their deaths with the phrase ‘Long Live the Emperor’ on their lips, instead called out “Mother!”’19

I will focus here on two anime works: Isao Takahata’s Grave of the Fireflies and Mori Masaki’s Barefoot Gen. In both of them weak female characters become the dependents of their respective male protagonists. In Grave of the Fireflies the male protagonist, Seita, is put in charge of his younger sister Setsuko due to the death of their parents. In Barefoot Gen the male protagonist, Gen, is forced to take charge of his traumatised mother after the rest of his family perish in a fire. In the words of Susan Napier, “Both films privilege the masculine as the dominant force in the family structures by showing two young boys taking care of their respective female relatives.”20 Marie Thorsten Morimoto argues that Japanese culture has entered a demasculinized state due to the overwhelming saturation of feminine cuteness in Japanese society, but is “still haunted by the images of a dead, absent, or inadequate father and a problematic masculinity”.21 This absent father figure pervades both Barefoot Gen and Grave of the Fireflies in which sons assume the fathers’ roles. Of course, many countries experience absent fathers during and following wars with the loss of male family members. However, the effect is especially conspicuous in “highly gendered”22 Japan where men are assumed to be “pillars” of the household” in a patriarchal society.23

In these films women are generally shown to be weak and fragile in contrast to the heroic strength of their male counterparts. According to Napier, while the female characters “remain an oasis of security, comfort, and strength in most pre-war film and literature” the female characters in both of these films “appear notably weak and tenuous.”24 Largely, female characters are dependent on their male counterparts, but more specifically, on young boys. This further emphasises their fragility and vulnerability.

In the immediate post-war period, American media gave wide coverage to a group of female victims of the nuclear fallout known as the Genbaku Otome. The Genbaku Otome, which translates as “A-bomb Maidens”, were a group of female victims of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings who travelled to America in order to receive treatment for their keloid burns and scars. In 1952, twenty-five of these women arrived in the United States, and became symbolic of the destruction caused by the A-Bomb. The media “focus[ed] on the women’s tainted beauty; their chances for marriage had been ruined by looking up at the sky at the wrong moment on that sunny morning in August 1945”25. Todeschini writes that “they exemplify a larger tendency in Japanese fictional representations on The Bomb to focus on young, female victims and single them out as especially pathetic symbols of the horrors of the bomb and exposure”.26 In post-war Japan the association of women with vulnerability meant that anime could evoke emotion simply by including helpless female characters.

Such scholars as Carol Gluck and John Treat identify characterizations of women and children in post-war Japanese anime as important elements in creating a “Victim’s History” focusing particularly on The Bomb. Gluck and Treat argue that these female characters are used to represent a fragile and wronged nation and evoke sympathy for Japan that distracts attention from the nation’s aggression and atrocities during WWII. They note, in particular, the international condemnation of biological warfare Japan waged in China and the disease experiments conducted on its own citizens.27 In the “pathetic symbols” of the Genbaku Otome, “the Japanese found an image of themselves, an image that they desired to embrace in the socio-political circumstances of post-war East Asia”.28 Susan Napier adds that the development of a Victim’s History was partly a result of collaborative American-Japanese efforts under the Allied Occupation to create an image of a post-war democratic Japan that would free the Japanese from an “inescapable fascist and militarist past”.29

Unlike much of the anime and manga at the time, these two films dealt directly with the attacks themselves, not just with their after-effects. Barefoot Gen unabashedly addresses them, particularly when Gen’s mother hears the news of Japan’s surrender and exclaims: “Tell me, why now? Why not before?!” Her questions reflect the view of Keiji Nakazawa, author of the original manga. In an interview he recalled a visit to his school by the Shōwa Emperor: “Dad had told me all about the emperor system, so I thought, ‘This is the guy who destroyed Dad and the whole family.’ […] I was hot as fire inside. ‘That guy caused us all this, killed Dad,’ and I wanted to fly at him.”30

This resentment toward the emperor was shared by many in Japan for his role in launching and prolonging the Pacific War. He was seen as obstinate and lacking in empathy for his comments on the bombing of Hiroshima: “I believe it was regrettable, but a war was going on, and although it was a great pity for the people of Hiroshima, I believe it was unavoidable.”31 His words are said to reflect his and the government’s total disregard for civilian lives. The mother’s questions in Barefoot Gen do not support Napier’s argument that this work ignores Japanese responsibility for the war. Barefoot Gen, more than any other A-bomb anime, expresses the resentment felt by many Japanese citizens towards their military and civilian leaders for, in the words of Robert J. Lifton, “having deceived the people and brought them to ruin, for not having prevented the bomb or even prepared the population for it, and particularly for failing to provide adequate help”.32

Dan Cavallaro proposes an alternate interpretation. Grave of the Fireflies “could be seen as a metaphor for the entire country of Japan during the war: fighting a losing battle, yet too stubbornly proud to admit defeat or accept help”.33 All throughout the film we see the elder male sibling, Seita, in a state of denial about the situation in which he and his sister find themselves. At first he appears to be maintaining this denial and simulating a state of constant positivity for the sake of his female sibling, but as the film progresses we begin to see his mental state deteriorate as he seems to start believing his own fabrications. His denial manifests itself in his constant belief that his father, a naval officer, is alive and that his return is imminent. Whenever Seita speaks of his father it is to say hopeful things, such as: “Dad will take revenge for us” and “If you don’t eat, I’ll be scolded by Dad!” This attitude could illustrate how state censorship concealed Japan’s military defeats. Yet, it could also show the resilience and sense of hope shown by Japanese people even amidst the devastating firebombing of Japanese cities.

This theme of hope and resilience in Barefoot Gen is reflected in its symbolism of rebirth and rebuilding of Japan. Nakazawa Keiji, author of the original manga version, explains that he chose the name Gen for its meaning of “source” or “origin.” “I named my main character Gen in the hope that he would become a root or source of strength for a new generation, one that can tread the charred soil of Hiroshima barefoot […] have the strength to say NO to nuclear weapons”.34

The children in both these films pose an odd paradox in that they can simultaneously represent the reality of Japan as a nation forced to re-invent itself as a result of catastrophe, while also conveying a more positive message of courage, resolve, and even hope. The children In Grave of the Fireflies are living in denial about the disastrous situation in Japan until Setsuko falls fatally ill. This contrasts sharply with the many scenes of mutilation and devastation in Barefoot Gen, a far more graphic depiction of war’s effects. Gen views much that is horrifying throughout the course of the film. He sees victims of The Bomb’s immediate effects who resemble the “jikininki” or “walking ghosts” of Japanese Buddhist mythology; the soldier and other victims of radiation poisoning; and, finally, the rotting man he and his adopted brother Ryūta care for in the weeks after The Bomb. Yet, despite the horror he encounters, Gen’s resilience and childlike optimism allows him to continue caring for his family.

Some might criticize the makers of Grave of the Fireflies for substituting appeals to emotion for a strong anti-war message. Gillies argues, on the other hand, that ‘the anti-war message is not overstated; Takahata has created an anti-war epic without resorting to finger-pointing. He shows the too-often forgotten victims of the war, the innocents who are caught in the crossfire of destruction.”35 The tragic consequences of a government’s empty promises of glory and false boasts of victory are conveyed in these works by their portrayals of child and female protagonists.

Depictions of these protagonists in later anime conveyed emotions in more human, rounded ways, exploring the complex feelings of guilt, frustration and sadness in Japan more fully than the earlier “hypercute” anime could. Some might view these innocent and vulnerable protagonists as evoking a “victim’s history” for the Japanese, an attempt to ignore Japan’s own war crimes. However, they can also be seen as an expression of the helplessness and resentment felt by Japanese civilians. The figure of the child protagonist is particularly significant in A-bomb anime. Napier notes that these works contain “many powerful scenes of human-scale interaction while at the same time [conveying] an innocent and childlike tone.”36 They are critical to maintaining the balance between emotional depth and escapism typical of the kawaii genre. These characters express the vulnerability felt by the Japanese in the wake of air attacks while conveying a certain amount of pride in their resilience and strength.

The Apocalypse Allegory – technology and characterization in later A-bomb anime

Contemporary A-bomb anime developed and matured in many ways beyond earlier works. Such anime as Akira and Neon Genesis Evangelion show how many Japanese dealt with their unresolved and repressed feelings towards the nation’s troubled past by representing The Bomb as some alien force or as an uncontrollable futuristic power. Writing on A-bomb literature, John Treat theorises that “when seeking the words to express what they wish to say, it is nearly rote for atomic bomb writers to tell us they despair of ever finding the words […] to convey the un-conveyable”.37 Contemporary writers of A-bomb anime encounter the same problem. Filmmakers of the “acute” generation deal with it by adding a strong fantasy element to their works. As Qi Wang argues in the essay ‘Troubled Identities at Borderland’ ,“[t]he fact that anime and manga reached the height of flourishing in post-war, high-pressure Japanese society offers the best explanation for the escapist nature of fantasy that characterizes these two media”.38

There is a far more reflective quality to these darker contemporary works produced after 2011. “It is currently estimated that more than three-quarters of Japanese citizens do not have first-hand experience of the Asia-Pacific War”.39 It is notable that these works never refer to The Bomb by name, but instead through euphemisms: “N2 Bombs” in Neon Genesis; “Vegatron Bombs” in UFO Robo Grendizer (1975-76); “Reaction Weaponry” in Super Dimension Fortress Macross (1982-83); and “Meteor Bombs” in Space Battleship Yamato (1974-75), to name a few. This apparent taboo distinguishes the “acute” generation from the “hypercute,” and represents complex contemporary Japanese attitudes toward The Bomb.

Arguably the most consistent theme in modern anime is the fear of technology expressed in the majority of films and television shows. These works convey a nightmarish vision of a future Japan as Frankenstein facing his monster, a world run by machines which humans created and have become inferior to. This fear of technology and its potential manifests itself in the form of energy fields, which can be manipulated by the post-apocalyptic and often mutated creatures that inhabit the barren lands of post-war anime. Brophy makes the argument in his essay ‘Sonic – Atomic – Pneumonic: Apocalyptic Echoes in Anime’ that post 1980s anime is far more preoccupied with energy and the effects of energy than its predecessors. It would make sense that these post-apocalyptic stories would develop a preoccupation with the effects of nuclear warfare in the ‘80s, given the number of second-generation survivors of nuclear fallout reaching maturity, as well as the ever-present fear during the Cold War. For a nation still dealing with the fallout of a nuclear attack, the possibility of another was understandably terrifying. Typically, post-1980s anime characters are identified by the type and power of their energy. Perhaps the best example of this is the 1988 anime Akira, written and directed by Katsuhiro Otomo.

Akira’s anti-hero protagonist, Tetsuo, is the “quintessential post-nuclear being – one born of conditions which both redefine our physical reality and allow for the re-invention of the human form”.40 This post-nuclear being is clearly representative of the second generation of nuclear fallout victims, and the simultaneously terrifying and exciting potential that Japan was reaching through its technological advances. When one speaks about the idea of energy as a visible and tangible force in modern anime, it is difficult not to think of such shows as Yu Yu Hakusho (1990-1994) or the earlier and far more popular Dragon Ball Z (1989-96), which earned cult-like followings and popularized energy as a weapon. This same premise of tangible energy used as a source of power is clearly seen in Akira. In this film believers of the return of the great God Akira abduct Tetsuo after his encounter with a mutant victim of the nuclear fallout of WW III who has gained psychic abilities as a result of his mutation. After his abduction Tetsuo finds he has acquired immense psychokinetic abilities and soon discovers that he can manipulate and control energy fields in order to utilise them as a weapon. As in most post-nuclear apocalyptic anime, “lines, rays, and beams of intense energy fall randomly across a metropolis, causing chaos and destruction, not unlike the infamous black rain of Hiroshima and Nagasaki”.41 In simple terms, he has become a human A-bomb.

The characters of the young psychic children in Akira echo the roles played by child protagonists in earlier anime and manga. These characters are frozen in a state of childhood due to the effects of scientific experimentation – with their deformed bodies serving as a warning of the dangers of technology. Tetsuo, however, is the ultimate symbol for the dangers of science in Akira. In the film’s dramatic denouement, we see Tetsuo undergo a multitude of horrifying physical mutations culminating in his final transformation into a grisly fusion of man and machine. (see fig. 2). Moore speculates that: “These themes of reanimation, rebirth and mutation predominate in Japanese manga and anime and are regularly linked to both the threat and promise of the science and technology in the wake of The Bomb”.42

The images of bodily mutilation become more extreme in the last fifteen minutes of the film, and this grotesque spectacle grows more and more graphic as the fight scene continues, serving to exaggerate the hideous potential which excessive technology could lead to. This display of mutation is not unlike the painfully detailed images shown during the long, slow-motion scene of The Bomb dropping in Barefoot Gen (see Fig. 3). Though “Body Horror” has become a trend in contemporary horror cinema,43 it is used here to remind a nation that they are still suffering from the physical and psychological effects of the fallout.

Another notable difference in contemporary anime is how gender roles are portrayed in Japanese society. In the opening scene, Deunan is seen in a soldier’s uniform, expertly battling a force of cyborg troops alongside her male comrades. As the film progresses we see her in more and more suggestive outfits, and sometimes even just in underwear. Deunan is a perfect example of how the qualities which have become representative of masculine and feminine in earlier anime, such as masculine strength and feminine fragility, are now bleeding into each other. The change in the role of women in anime from their portrayal in the immediate post-war period could be seen as Japanese finally coming to terms with their “victim’s history.” However, it is more likely representative of Japan’s ever-growing fetishization of young women. This is evidenced in the recent renaissance of Hentai – or manga and anime pornography – in popular Japanese culture. The popular manga Appleseed caters to the well-documented fascination with sexuality associated with young girls in Japanese culture. Just as with the vulnerable damsels in distress of shōjo manga in the immediate post-war period, the increasingly explicit content of more contemporary anime and manga with their fetishized female characters could be seen as yet another distraction from the history of Japanese imperialism and war atrocities of the recent past.

Much like live-action apocalyptic American thrillers of the 1970s, such as Logan’s Run (1976), Genesis II (1973), and Deathsport (1978), these modern anime films are set not only in the future, but often also in a world where the devastation is decades if not centuries old. The simultaneous fascination with and fear of technology as a source of power and weaponry in these films suggests that Japan remains confused as a nation about the meaning of its nuclear legacy. Like its characters, the genre of A-bomb anime seems not yet fully developed and remains “suspended in the teenage realm between childhood and maturity”.44

I would argue that the progression from kawaii to acute animation does not, as Moore suggests, represent the development of a straight-forward and self-aware attitude toward The Bomb. While contemporary acute anime deals more directly than earlier cute anime with the ever-present danger posed by the increasingly rapid development of technology and science in Japan, the futuristic and fantastic settings of these films and TV shows become barriers to fully developed psychological portrayals of their characters.

Conclusion – A memory-shaping medium

Though in this essay I have questioned some interpretations of A-bomb anime, its value as an innovative art form cannot be denied.

“Adaptation into another medium becomes a means of prolonging the pleasure of the original presentation, and repeating the production of a memory”.45

Adaptation into any medium is an effective way of preserving and reliving a memory, whether pleasurable or not, and animation is no exception. Cavallaro argues that it is more effective to depict the horrors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in an animated form as it would have been ‘”bogged down in realism”’ of a live-action film “and the final product would not, therefore, have been as “pure’” and “abstract.”46 She also notes that “In many cases, the fact that it is animated gives simple actions and scenes a beauty and innocence that would not have existed otherwise, creating all the more contrast with the harsh and painful realities experienced by the characters”.47 This contrast between the beauty of animation as a medium and the ugliness of the horrors it is depicting serves to support the validity of animation as a “memory shaping medium”.

This contrast applies especially to the more gruesome aspects of such films as Barefoot Gen and Grave of the Fireflies as we are used to animation depicting princesses, far-off lands and happy endings. When presented with something so horrific as nuclear war through childhood characters in what used to be called “cartoons” it is natural for the viewer to feel uncomfortable. Yet, by using an ordinarily apolitical medium to explore serious political and social issues, these works serve to remind us that the history they address permeates all forms of art portraying modern life, even manga and anime.

Notes

Aviad E. Raz, Riding the Black Ship: Japan and Tokyo Disneyland (Harvard: University Press, 1999) p. 163

Ryan Holmberg, “Tezuka Osamu and American Comics”, The Comics Journal, (accessed October 3rd, 2020)

Frederik L Schodt, The Astro Boy Essays: Osamu Tezuka, Mighty Atom, Manga/Anime Revolution (Stone Bridge Press, 2007) p.45

Yoichiro Sato, Norms, Interest and Power in Japanese Foreign Policy (Palgrave Macmillan, 2008) p.25

Helen McCarthhy, Hayao Miyazaki: Master of Japanese Animation (Berkeley: Stone Bridge Press, 1999) p. 10

Dani Cavallaro, Anime and the Art of Adaptation: Eight Famous Works from Page to Screen (North Carolina: McFarland Publishing Ltd., 2010) p. 30

Takeo Doi, The Anatomy of Dependence: The Key Analysis of Japanese Behavior. English trans. John Bester (2nd ed.). (Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1981) p. 197

Robert Jay Lifton, Death in Life: Survivors of Hiroshima (North Carolina: University Press, 1991) p. 22

Robin M. LeBlanc, ‘Thepolitics of gender in Japan’ in Routeledge Handbook of Japanese Culture and Society, Victoria Bestor and Theodore C Bestor with Akiko Yamagata (eds.) (Oxford: Routledge, 2011) pp. 116-129, p. 117

Naoko Shibusawa, America’s Geisha Ally: Reimagining the Japanese enemy, (Harvard University Press, 2006) p. 227

Tsuneishi Keiichi, ‘Unit 731 and the Japanese Imperial Army’s Biological Warfare Program’, Asia-Pacific Journal Volume 3, Issue 11, (November 24, 2005)

‘Barefoot Gen, the Atomic Bomb and I: The Hiroshima Legacy’ in The Asian-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, interview by Asai Motofumi, online source [Accessed 25/10/12]

Kawaguchi Takayuki, ‘Barefoot Gen and ‘A-bomb Literature: Re-recollecting the Nuclear Experience’, Comics Worlds and the World of Comics Conference, Kyoto Seika University, December 2009, Transcript available , [Accessed, 22nd November 2012] (p. 242)

Tony Yao, ‘Nuclear Weapons: Deadly Psychological Weapon (Barefoot Gen)’ on Manga Therapy, (First Appeared 17/02/11), online source [Accessed 17/10/12]

John Treat, Writing Ground Zero: Japanese Literature and the Atomic Bomb (Chicago: University Press, 1995) p. 21-30

Qi Wang, ‘Troubled Identities at Borderland — Fantasy about the Past and the Future in Anime’, International Journal of Comic Art, Vol 7, p. 406, 2005.

Kelly Hurley, ‘Reading Like an Alien: Posthuman Identity in Ridley Scott’s Alien and David Cronenberg’s Rabid’ in Posthuman Bodies, Judith Halberstram and Ira Livingston (eds.) (Indiana: University Press, 1995) p. 203