Abstract: Prime Minister Abe Shinzo has been widely criticized for ineptitude in response to the coronavirus pandemic. Keen to host the Olympics in 2020, he put public health at risk. Strong international criticism finally forced the IOC and Abe to accept the inevitable and defer the Olympics until 2021. Now both parties are now trying to claim credit for making this decision. The Japanese policy of limiting testing kept policymakers and citizens in the dark and handicapped responses to the outbreak. As the number of infections surges, the government is playing catch up. The combination of an accelerating COVID-19 outbreak in Japan and imminent global economic recession will hit Japan hard and could lead to Abe’s ouster. For now, there are growing concerns that he may exploit this crisis to advance his political agenda of constitutional revision.

Prime Minister Abe has been widely criticized for his poor crisis management skills during the coronavirus pandemic. He was so keen to host the Olympics this summer that he put public health at risk in order to keep that scenario on track. But the global pandemic made this untenable as lockdown after lockdown, border by border, movement and transport has been curtailed to contain the outbreak. These extensive travel restrictions meant that no matter what Abe wanted, many athletes would not be able to compete.

After a chorus of calls from Olympic athletes, sports federations and from leading participant countries in favor of postponing the Olympics due to the pandemic, the IOC and Abe finally accepted the inevitable and agreed to defer the Olympics until 2021.

This is a stunning climbdown by Abe who was adamant to the end that the games would proceed as scheduled. Yet again rather than leading, Abe was overwhelmed by events and tardy in making a hard choice. Despite a cascade of scandals ranging from cronyism to document tampering on top of policy miscues and flipflopping, Abe hasn’t yet paid a political price for his lackluster performance. This may change as the number of infections rises and the global economic recession batters the Japanese economy.

As of mid-March, Kyodo reports that almost half of Japanese support Abe, up a remarkable 9 points since February, while at the same time the Mainichi found that 49% support his handling of the crisis as opposed to 45% who don’t. This appears to reflect the rally-around-the-leader phenomenon. Moreover, the Japanese media’s extensive coverage of Trump’s cringeworthy press conferences makes everyone here realize that things could be so much worse.

But the mood may be shifting as the Kyodo poll at the end of March found Abe’s support rate dropped to 45%. He has sunk in the polls before and bounced back, so it’s too soon to predict how this will play out.

Spin Doctors Ahoy

Team Abe has cultivated media boosters who are portraying him as responsible and resolute in postponing the Olympics to protect the nation from the pandemic. NHK has played a key role in this campaign aimed at burnishing Abe’s reputation. For example, on March 24, NHK political analyst Iwata Akiko, who is reliably obsequious towards Abe, responded to his Olympics postponement announcement by presenting a fanciful narrative of his behind the scenes proactive leadership and resolute decision-making that earns high points for chutzpah if not veracity. This version is inconsistent with other reports concerning Abe’s feckless flipflopping and erratic decision-making on school closures in the face of the coronavirus.

IOC Chairman Thomas Bach and PM Abe Shinzo

According to the Washington Post’s Tokyo bureau chief Simon Denyer, ”It’s clearly the spin the government is pushing. The IOC wouldn’t make up its mind, so Abe did. It all came to a head in the week of March 8, which is when the JOC’s Takahashi Haruyuki broke ranks with the Tokyo 2020 board and said we needed to talk about postponement. The same week WHO called it a pandemic and senior figures within the LDP started pushing Abe to postpone.”

He added, “I think what Abe feared was the scenario Dick Pound had laid out. The IOC waits until May and then decides to cancel completely. Nightmare on two counts because no Olympics, but also Japan looks like it was kept out of the loop and didn’t care about the athletes (exactly what happened with the decision to move the marathon to Sapporo).”

Moreover, “Trump also woke Abe up by calling for a postponement, but also backed the idea that it shouldn’t be cancelled. Shiro Tazaki (NTV commentator and Abe ally) told us this was a “lifeboat” for Abe because he could then start to float the idea of postponement without worrying he’d lose the Games entirely. So within days Abe proposed this idea of the Games taking place in a ‘complete manner’ and took that idea to the G7 and got them behind it.”

Denyer concludes, “The IOC will give you a different version of events of course, where they will take all the credit for wise decision making and had to push Japan. If you ask me: neither side really wanted to make the decision and had started to look irresponsible for not doing so. Now it’s been made, and everyone knows it was the correct decision, both want to take credit.”

Another veteran reporter who has covered a few Olympics explains, “What I have heard from a couple of people is that Abe did not want to postpone. So Bach went along with it for a bit. Abe had to be pushed. Some speculate that John Coates, who is the IOC member from Australia who is very close to Bach, intentionally made it known that Australia WOULD NOT go to the Olympics this year. Canada said the same. Athletes also jumped in. I am told basically that Abe was then told to make a postponement suggestion to Bach, who accepted – making it look like Abe was in charge.” (Personal communication March 2020)

Reuters concludes, “In the days leading up to the decision, organizers of the Games were under pressure from major players in global sports: sponsors wanting updates, powerful sports federations worried about athlete safety, and Japanese officials seeking to maintain a united front to support the 2020 Games. But ultimately, it was the growing chorus of concerns from famous athletes and nations under lockdown that sunk Tokyo’s hopes to hold the Olympics in July, according to senior officials at the IOC and on Tokyo’s organizing committee.”

In this version, the IOC and Abe are reactive, initially misjudging the situation badly and only belatedly coming to terms with what had to be done when there really was no other choice.

The Washington Post provides the most nuanced and detailed dissection of this drama, suggesting that IOC chairman Thomas Bach orchestrated the postponement and presented Abe with a fait accompli.

According to the Post, “On March 22, a Sunday morning, Bach’s outlook shifted. He awoke to news of a coronavirus outbreak starting in Africa and read reports of accelerating growth of cases in the United States and South America. He called an emergency meeting of the IOC’s executive board.Bach then called Yoshiro Mori, the president of Tokyo 2020’s organizing committee. Bach said he told Mori to be prepared not only to discuss potential scenarios, but to talk with Abe and come up with specific plans for a postponement.”

However, “Bach couldn’t postpone the Olympics without Abe’s blessing and Japan’s ability to manage the web of on-the-ground headaches postponement would cause — ticket refunds, venue upkeep, rescheduling local events, etc. Having felt overstepped once before by the IOC, Abe couldn’t postpone them without showing his nation he held control of the decision.”

But the IOC took the initiative, “Bach wanted to drive this through,” said Michael Payne, a former IOC marketing head who maintains close ties to the Olympics. “But not causing the Japanese to lose face.”

To ensure this outcome, “Bach contacted the Tokyo 2020 organizing committee and made his plans clear. He wanted to talk with Abe the next day, and in that call, Bach said, he wanted Abe to outline a proposal for postponement, which Bach then could take back to the IOC’s powerful 15-member executive board.” Such are the international dynamics of face-saving and glory grabbing.

On March 28, NHK’s Iwata struck again in commenting on Abe’s nationally televised address in which he warned that the situation is dire and requires unified long-term efforts and sacrifice to contain the outbreak along with bold economic countermeasures. His tone was markedly different from his previous two speeches about the coronavirus, suggesting that “the rate of infection could explode.”

Iwata merely reiterated his main points without pointing to the ten weeks of inaction and dithering that preceded this belated nod to grim realities. Nor did she mention Abe’s lack of specific measures to limit the outbreak. Instead Abe sought to project the image of a leader on top of the situation and rebuffed a question concerning how the government had been hiding the true number of cases. This question relates to assertions that Abe sacrificed public health to save the Olympics by not acting sooner.

Since NHK news has the largest viewership and enjoys considerable credibility, Iwata’s reticence about the discrepancies between Abe’s speech and actual slow-motion response must have been welcome in the kantei (Prime Minister’s office).

An Asahi editorial on March 27 provides a sobering reality check, warning that Japan’s healthcare system is ill-prepared to tackle a surge in cases, as nationwide there is an inadequate number of facilities for infected people and a lack of ventilators for those who become seriously ill.

Viable?

Is 2021 viable? Richard Lloyd Parry of The Times wonders, “if there is any sound epidemiological reason for believing that the world will be fit for an Olympics in 16 months time, given the time it will take to create, manufacture and administer a vaccine internationally. The summer 2021 deadline may have as much to do with Abe’s scheduled retirement in September 2021 as with science.” (Personal communication March 2020)

Another journalist asks, “what happens if the virus goes into remission for six months or a year, and then reappears? That happened with Spanish Flu. It arrived in several waves. In Japan, the first cases in October 1918 and I think the last outbreak reported was reported in late 1921 or thereabouts –after killing at least 470,000 people. I know historical comparisons like this are faulty, but I don’t hear much talk in political circles about the possibility of further outbreaks next year or 2022, although one doctor on NHK warned that we still don’t know if the virus will mutate, which might make it ineffective against any vaccine now being developed.” (Personal communication March 2020)

Political Ramifications?

Whatever the spin, it doesn’t appear that many Japanese are all that concerned about postponement. Before Abe’s announcement, some 70 percent of Japanese already doubted the Games would proceed on schedule, and nearly two-thirds believed they should be postponed. After the announcement, 79 % of Japanese approved the delay while 6% prefer cancellation of the Games.

In contrast, Koichi Nakano, a political scientist at Sophia University, doubts, “whether postponing it by a year is such a great idea because it’s a lot like letting Trump put off the election by a year. Imagine what he might do.” He adds, ”Sure, Abe is not exactly Trump, but Japan doesn’t have the political opposition, civic activism, and press freedom the US has. Wiping out the coronavirus in one year is a very hard task and this will be used as an excuse for Abe to rally the entire nation behind him for this war-like national purpose.” (Personal communication March 2020)

He warns that, “The fight against the coronavirus has already been compared to war, but only sparingly in Japan so far because Abe wanted to host the Olympics as planned. If it’s a war, it’s as much an information war as an epidemiological one, and once given a pass for a quasi-war posture, his enemy will be internal dissent as much as the virus itself. It’s a very scary scenario. Total mobilization of the nation for the persecution of war in the name of the Olympics. One-year dictatorship condoned by the international community. If Abe has good advisors, he will take the offer.”

Relatedly, the Asahi slammed national emergency legislation Abe rammed through the Diet in early March, raising questions whether he has the judgment and can be trusted. In this editorial the Asahi asserted that “Abe and other senior administration officials have taken a raft of actions that indicate a serious lack of understanding about the real meaning of ‘the rule of law.’ This is all the more worrisome because a series of political reforms have significantly increased the power of the administrative branch.” Additionally, “In responding to the coronavirus epidemic, Abe has made some abrupt decisions to take drastic measures without seeking advice from experts, including calling for voluntary restrictions on events and nationwide school closures.”

It is also troubling that Abe is capitalizing on this crisis to advance his political agenda. The pandemic may help Abe make the case for a constitutional amendment granting the prime minister the power to declare a state of emergency and suspend civil liberties. Crisis and postponement thus may generate momentum for Abe to realize his longstanding dream of constitutional revision.

Reacting to this possibility, musician Sakamoto Ryuichi weighed in against government efforts to boost patriotism and exploit the crisis for political gain, warning that national emergency powers could be abused as in wartime Japan.

Wishing Risk Away

There has been considerable speculation about why Japan’s rate of infections has been so low, focusing on cultural norms. Some attribute this to a combination of good personal hygiene, the lack of handshaking or kissing, widespread wearing of masks, elderly isolation, cleanliness and good luck.

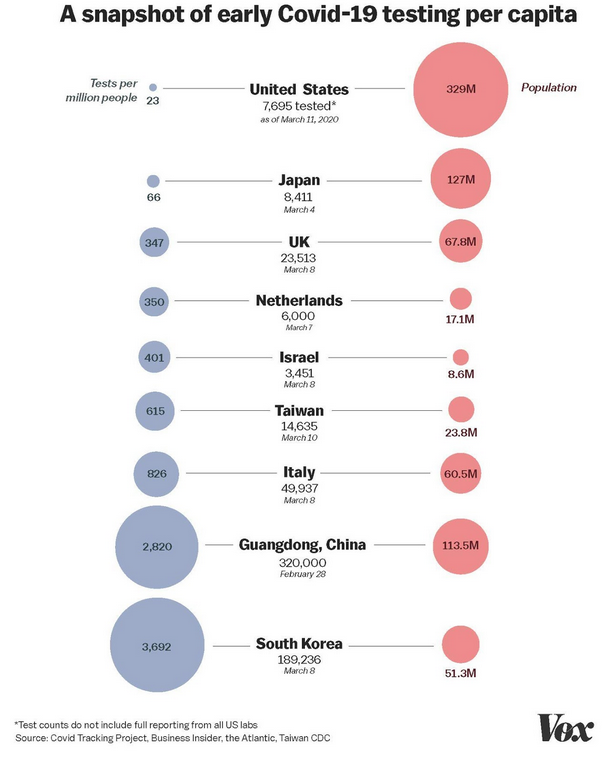

But skeptics point out that the official numbers are not reliable because, compared to many other countries, there has been relatively little testing in Japan. It has been very difficult to get tested, explaining why per capita testing in Japan lags way behind South Korea, 66 per million population versus 3,692 as of mid-March. As a result, policymakers are shooting in the dark because they don’t know the scale of the problem. As testing ramps up, so too will the official number of infections.

The following chart of testing as of early March 2020 provides a graphic and sobering comparison.

Basic COVID-19 testing numbers for Japan as of March 16, 2020:

- Tested: 13,026*

- Detected: 1,496 (both symptomatic and asymptomatic cases)

- Deaths: 24

Sources: Toyokeizai, MHLW, Japan Times, Vox,

*Note added March 18, 2020: MHLW data gives two sets of testing figures; daily report for Mar 18 now gives 33,212, which is noted as “total number of responses received from local governments and other organizations.” But the table on the same page gives 15,354, categorized as “tested by PCR.” It is not clear what the difference is. Regularly updated information is avaialble at these links.1

Tokyo Governor Koike Yuriko has urged Tokyoites to work from home and stay inside on weekends, suggesting she will impose a lockdown if there is a surge in cases. For much of March Japan seemed an outlier with no drastic containment measures and few infections, but that rosy scenario appears to be ending as cases across Japan are rising and may force Koike to impose a strickter lockdown.

Legacy

PM Abe Shinzo Hamming it up as Super Mario at Rio 2016 Olympics Closing Ceremony

There has been a devastating impact on the economy as the Nikkei stock average has plunged, the economy is contracting, and the once booming tourism sector is moribund. Everyone anticipates that the pandemic will inflict more damage to the economy and generate job losses that will hit households hard, and further dampen consumption, already reeling from Abe’s ill-judged 2019 sales tax increase. COVID-19 defies easy predictions but does promise awful consequences that result from a profound crisis in global healthcare stemming in part from neo-liberal reforms and stark inequalities.

Postponing the Olympics adds to already gloomy economic prospects for Japan but does offer a glimmer of hope for a rebound in tourism in 2021 and may have implications for Japan’s political leadership. Abe’s third term as LDP president will expire in September 2021. The dates for the Games are still up in the air but if the pandemic is contained, they will probably be held before that, meaning that Abe can exit with at least some positive legacy or hang on for a fourth term if his colleagues agree to another change in the party’s rules. With Abenomics and ‘womenomics’ in shambles, and assuming no constitutional revision by then, will Abe be content with the mixed legacy of whitewashing secondary school textbooks, rolling back transparency (2013 Special State Secrets Legislation), the pacifist-renouncing Abe Doctrine ( 2015 Collective Self Defense Legislation and 2015 US-Japan Defense Guidelines) and promoting a nuclear energy revival despite strong public opposition and a more than $600 billion bill for the Fukushima cleanup and decommissioning of reactors? The Olympics may indeed prove a lifeline, but the coming economic storm combined with lingering scandals and a crippling pandemic could escalate Abe fatigue and hasten his exit.

Notes

More updated testing data in Japan are available at Our World in Data and Toyo Keizai Online.

Also, LINE has announced it is collaborating with MHLW to conduct a massive COVID-19 symptom survey of its users in Japan. Initially limited to Tokyo, Kanagawa, Chiba, Saitama, 160,000 people have responded in the initial survey.

(Links ccessed on March 29, 2020).