Abstract: Counterinsurgency tactics for winning hearts and minds are key weapons in state efforts to suppress rebellion and the possibility of rebellion. Always predicated on the threat of state violence, hearts and minds counterinsurgency is usually thought to originate in British or French strategies for managing insurgency in their colonies in Asia, especially in suppression of the 1948-1960 communist insurgency in Malaya. However, work with archival data, a genealogical approach to clear, hold and protect population management, which is a key principle of hearts and minds strategy, and careful review of scholarship on Japan’s colonial military and governance (especially but not only in Japanese language) indicates that hearts and minds/hold and protect counterinsurgency principles have origins in imperial management of insurgency in Japan’s colonies. It is also possible that elements of imperial Japanese “soft” counterinsurgency strategy undergird American and British hearts and minds counterinsurgency strategies in Malaya and South Vietnam in the 1950s and 1960s.

Keywords: Japanese imperialism; Japanese counterinsurgency; legacies of Japanese colonialism; history of Japanese counterinsurgency; hearts and minds counterinsurgency; strategic hamlets; Manchuria; South Vietnam; Malaya

“Soft” Counterinsurgency

Persuading rather than terrifying people to support the state instead of insurgents remains a key weapon of counterinsurgency theory and practice: “soft” strategy. In a 2010 Meet the Press interview, Gen. David Petraeus, one of the lead authors of United States counterinsurgency strategy and at the time of interview, commander of the International Security Assistance Force in Afghanistan, set out a typical hearts and minds counterinsurgency strategy beginning with violent clearance of rebels from a defined space, hold of that space, protection of the population in that space, and culminating in successful persuasion of their loyalties. Petraeus concluded: “At the end of the day, it’s not about their embrace of us, it’s not about us winning hearts and minds, it’s about the Afghan government winning hearts and minds. This isn’t to say that there is any kind of objective of turning Afghanistan into Switzerland in three to five years or less. Afghan good enough is good enough.”1 For managers of hearts and minds counterinsurgency operations, “soft” tactics depend on state violence for their success, and success is always measured in terms of what is “good enough”.

In popular consciousness (and in the thinking of Gen. Petraeus), hearts and minds counterinsurgency descends from United States and South Vietnamese government counterinsurgency tactics in Vietnam in the 1960s and early 1970s. Many professional historians push the lineage a little further back to British suppression of communist insurgency in Malaya in the 1950s.2 Others have tried to follow it to the British imperial response to insurgency in the Baluchistan region of Afghanistan in the late 19th century3 or to French counterinsurgency tactics in Tonkin (North Vietnam) and Madagascar, also at the end of the 19th century.4 What is missing from most of these accounts of the lineage of hearts and minds counterinsurgency, however, is Japan. In a footnote to a seminal study of Chinese politics and Chinese communist governance of the Shaan-Gan-Ning region before 1945, Mark Selden remarks, “The Japanese have not received sufficient recognition for the design and implementation of counterinsurgency.”5 I think Selden refers here primarily to the brilliant savagery of Japanese state violence in the Japanese colonies, but “insufficient recognition” also characterizes the state of our knowledge of Japanese “soft” counterinsurgency about which there is scant discussion in any language. Yet, Japan’s public commitments to Pan-Asian programming and benevolent patronage of Asian modernization in its imperial ideology, along with the need to conserve production of resources for the imperial effort, meant that managers of the imperial state understood the benefits accruing from forms of counterinsurgency that created safe, productive, and compliant populations. Always operating in concert with state violence, Japan used vestigial and fully realized, formal and informal hearts and minds counterinsurgency throughout its colonies from the very beginning of its modern imperial project in 1869. What is more, in the postwar period, Japanese hearts and minds methods seem to have persisted and recurred in British and United States’ counterinsurgency theory and practice in Malaya and Vietnam.

Seized Hearts

Modernity and theories of modernity produce hearts and minds counterinsurgency. If James Scott is correct that modernity has been a project making the illegible legible,6 then hearts and minds counterinsurgency seeks to transform the radical illegibility posed to state power by rebellion into an extreme and miniaturized legibility. In hearts and minds counterinsurgency the state administers the core goods of modernity — security, rationality, regulation, education, capitalization — to a small and highly concentrated population contained in a space purpose-built as antithesis to the illegibility of insurgency. The bet is that the rewards of modernity are more likely to secure loyalty than any goods offered by insurgents.7 Imperial Japan was almost missionary in its determination to be modern and to impose modernity wherever the Japanese state alighted. No 19th or 20th century empire went at its colonies with more talk and more application of modern forms such as centralized government, industrialization, double entry accounting, effective banking systems, state-controlled education, communications and transport infrastructure, cadastral surveys and the rule of private property, and formally encoded juridical procedures enforced by rational, armed security forces, than the Empire of Japan. The Japanese state and its governments portrayed the realm as beset by threats – illegibilities – best countered by modernization backed up by military and economic power. At home and in the colonies, otherness, disagreement, criticism, heterogeneity and rebellion were met with implicit and explicit threats of state violence and strategic applications of modern goods. Resistance could seem like abjuration of the goods of modernity; submission, a modernizing act.

This began early. In colonial Hokkaidō, the army and colonial authorities sought to contain and abolish the disorder posed by Ainu with forced relocation into new communities. It may have been that relocations in Hokkaidō were inspired by what Japanese colonial authorities had learned or heard from American advisors. Men with both direct and indirect experience in management of Native Americans in the western United States played significant roles in the early colonization of Hokkaidō. In 1870, Kaitakushi (Hokkaidō Colonization Commission) hired Horace Capron to advise on commercialization and eventual mechanization of agriculture in Hokkaidō. His resumé included dispossession and relocation of Native Americans from their lands in Texas after it was wrested from Mexico in the Mexican American War of 1846-1848 and opened up to large-scale settlement. To work with him in Hokkaidō, Capron hired men with similar credentials: surveyors, geologists, and agronomists with experience in management of lands taken from indigenous Americans and in removal of native peoples to make way for railroads, mines, and farms.8 Though the Ainu posed little real threat of insurgency in Hokkaidō, they did not surrender to Japanese rule passively: Ainu did not rebel but they were often reluctant.9 The Japanese state set about using modernity to vitiate Ainu difference and the threat it posed to modern order. By the end of the 1880s, many Ainu had been forced into new communities on lands often far from ancestral territories. Here, they were subject to the suasions of the modern state while their lands were released for exploitation and profit taking. What had been gleaned from American advisors about managing reluctance and avoidance and the potential threat of conquered populations now intersected in Hokkaidō with Japanese ideas about a modern national subject and Japanese anxieties about the security of the state. The key imperial Japanese counterinsurgency principles of clearance, hold, protect, and formation of loyal or at least submissive hearts and minds first emerged here.

The techniques sketched out in management of Ainu in Hokkaidō went into an active conflict zone in colonial Taiwan between 1902 and 1920. The army, in collaboration with colonial administrators, Japanese anthropologists at Taihoku Imperial University in what is now Taipei, and local pro-Japanese leaders, developed and refined Japanese hearts and minds counterinsurgency to put down a fierce armed rebellion by Formosa First Peoples. In Hokkaidō, clearance had comprised forced relocation of Ainu into communities where they could be held, protected, and persuaded. In Taiwan, clearance, hold, and protection began with a modern adaptation of an old Chinese military strategy for defense against barbarians. The Japanese military and civilian authorities built a guard line of mines, sentries, forts, deforestation, and electrified fencing which bisected the eastern highlands of Taiwan where most surviving Formosan First Peoples lived. On one side of the guard line lived First Peoples opposed to Japanese rule or not submitted to it: “raw barbarians [seiban]”. On the other were First Peoples who had submitted to the imperial Japanese state: “cooked barbarians [jukuban]”. This was a savage space. Traversing it required a convincing demonstration of submission to Japan and its modernizing project. The raw could become cooked and cross the guard line only after convincing Japanese authorities and pro-Japanese Formosan First Peoples’ community leaders of submission to the Empire and its government on Taiwan. Crossing also entailed agreement to removal into villages purpose-designed and built at new sites by the state.

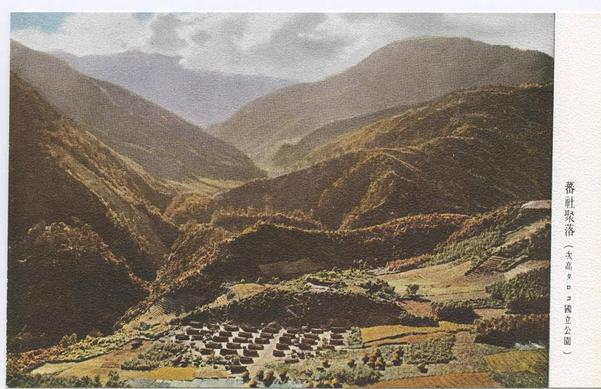

Japanese postcard showing a modern village for Taiwan First People in Taroko, circa 1933.

Source: East Asia Image Collection, Lafayette College.

As in Hokkaidō, relocation in Taiwan freed up resources for exploitation, in this case, the camphor forests of upland Formosa. Relocation into new villages also isolated “cooked” First People from contacts with “raw” insurgents and grouped them together for efficient delivery of a range of transformative Japanization and modernization programs. Japanese and local state managers viewed clear, hold, protect, and persuade hearts and minds counterinsurgency upon Taiwan First Peoples as a considerable success. Armed insurgency petered out until it exploded again in the 1930s. Bunun, Atayal, Seediq and other First Peoples gained reputation for fluent Japanese language skills, meticulous performance of Shinto ritual, and great valor as volunteer combat troops in the Imperial Japanese Army.10 This is not to say that Japanese hearts and minds counterinsurgency methods utterly transformed Taiwan First People into local versions of metropolitan Japanese subjects; indigenous languages and names, traditions were treasured and kept; identities endured. Bunun and Atayal spaces in colonial Taiwan did not become blebs of Chiba Prefecture, but the Japanese-ness of First Peoples was “good enough”; hearts and minds counterinsurgency in First People’s Taiwan achieved its goals.

It may be that the perceived success of hearts and minds tactics in ameliorating difference in Hokkaidō and quelling armed insurgency in Taiwan encouraged managers of the imperial Japanese state to take hearts and minds up again when confronted with rebellion in Manchukuo after 1931. Even before the Japanese conquest of Manchuria and establishment of the Manchukuo client state in 1931-1932, armed Chinese and Korean nationalist groups, armed militias loyal to local warlords, and bandit units formed primarily in response to deep poverty in the region threatened Japanese interests in northeast China. Anti-Japanese groups repeatedly attacked Japanese railroads in Manchuria. Mantetsu sought to protect its lines and facilities by building fortified villages at strategic points along the lines and moving local Han and Manchu populations into them. Residents received preferential treatment in regard to food, health and education. In return, they accepted ideological suasion and responsibility for surveillance of each other’s loyalty to Japan, of the railroad and its adjacent territories, as well as armed defense if required.11

The real insurgency problem for Japan in northeast China emerged, however, in areas close to the border with colonial Korea and somewhat beyond, as far North as Jilin, where a sizeable Korean population resided. In 1930, around 400,000 Koreans had their homes in the Jiandao region of Manchuria; another 200,000 Koreans lived in other parts of Manchuria.12 The Jiandao Korean communities existed in a state of precarious resentment. Many had felt compelled to leave Korea for settlement in Manchuria where they sought land to farm after the great Japanese cadastral survey of land in colonial Korea between 1912 and 1918 destroyed the traditional rights of peasants to cultivate land owned by the pre-Japanese Yi state and/or the pre-Japanese elite.13 But in Manchuria, Koreans faced both formal and informal discrimination from Chinese authorities and Chinese neighbors. As well, the Japanese consular police in Manchuria and the Japanese Government-General of Korea across the border viewed Koreans in Manchuria as potential insurgents against Japanese rule in Korea and Japanese interests in Manchuria. Korean nationalist organizations operated in the area, notably, the Northeast Anti-Japanese United Army, which included Kim Il Sung and others who would eventually found the post-1945 North Korean state.14 There had been a Korean armed uprising in Jiandao in 193015 followed by increased anti-Japanese sentiments and insurgent activity in the Korean districts of Manchuria and elsewhere concomitant with the Japanese conquest of all of Manchuria and establishment of the Manchukuo client state in 1931-1932.16

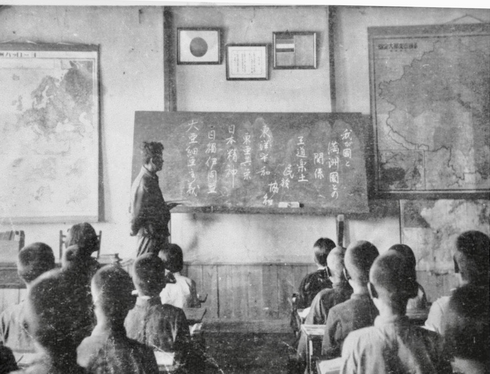

Military training for children living at a Japanese protection village in Manchukuo.

Source: Piao Renzhe, ‘Manshū’ ni okeru Chōsenjin ‘Anzen nōson’ ni kansuru ikkōsatsu [A study of Korean protection villages in Manchuria], Hokkaidō University Graduate School of Education Research Bulletin, Vol. 106, pp. 103-117.

Japan’s Kwantung Army went about the business of clearing Manchuria of resistance with considerable violence, but once the Guomindang and warlord armies had been destroyed and Manchukuo established, it worked with Manchukuo security forces and the Government General of Korea to find ways to head off insurgency in Manchuria using hearts and minds methods. After a mostly unsuccessful effort to overlay a hybrid local community civil law and order system comprising a version of Japanese tonarigumi (neighborhood association responsible for small scale defense and safety) and a version of Chinese baojia (neighborhood self-defense and contribution system),17 the counterinsurgency turned to hearts and minds strategy based upon clearance of threat, hold of cleared space, protection of the space and its population, and ideological persuasion.18 The new settlements contrived for Ainu in Hokkaidō, the new villages built for loyal Taiwan First People, and the protection villages built for the South Manchuria Railroad Company now recurred in Manchukuo as protection villages and collective villages.19 At first, eight protection villages were built and populated in 1933 by order of the Government General of Korea for locals of Korean ancestry in Jiandao.20 These seemed good enough. Residents of the protection villages may not have converted to the Japanese cause, but the Japanese hearts and minds program gave them cause to submit. Cutting insurgents off from the support and succor of local Korean communities slowed rebellion down but also created a sense of safety and order among residents whose livelihoods had been much disrupted by anti-Japanese activities. The Government General of Korea thus went on to build more protection and collective villages in Manchuria until 1934 when the Manchukuo government in the form of elements of the Kwangtung Army embedded in the Manchukuo security forces took over. By the end of 1937, 10,629 fortified protection and collective villages with a total population of more than 5.5 million Koreans, Chinese, and Manchus dotted the remoter regions of Manchukuo. More than 2,500 new villages were slated for construction in 1938.21

Japanese education in a Manchukuo protection village for Koreans, 1942

Source: Piao Renzhe, ‘Manshū’ ni okeru Chōsenjin ‘Anzen nōson’ ni kansuru ikkōsatsu [A study of Korean protection villages in Manchuria], Hokkaidō University Graduate School of Education Research Bulletin, Vol. 106, pp. 103-117.

Protection and collective villages in Manchukuo had fortifications and their own militias sponsored by regional police. Basic roads and telephone networks were built between protection villages so that they could communicate with each other and with local police garrisons in the event of attack by insurgents. All residents carried identity cards and resident passes to control access to their own villages and to adjacent arable land. Each village had a community association charged with preserving order, keeping residents in line and loyal to the Empire.22 In the beginning, living conditions in the new villages could be dangerous and rough. Japanese and Manchukuo reports from the time describe privation and starvation and note cruel absurdities: one fortified village was built far from where its residents grew their crops but the system of identification cards and passes barred them from going to their fields;many starved. After a series of damning Japanese reports on conditions in the villages, authorities did what they could to address resource issues, viability of defense village economies, and village facilities, including schools and community spaces. And, most importantly, from the standpoint of state managers, the tactic of linking population control with state violence and the fear of state violence, systems of reward, and ideological education in Manchukuo reduced the power of insurgents and stabilized rural society: by 1939, insurgency in Manchukuo had been fairly effectively suppressed.23 Antipathy to Manchukuo and Japan and sympathy for insurgents endured despite the Japanese hearts and minds counterinsurgency system, but the relative stability and security brought into existence by Japanese/Manchukuo strategy, along with the ever-present threat of state violence, kept people in line24 and that was good enough.

Over time, systematization emerged from unsystematic experiences with “soft” tactics in Hokkaidō, Taiwan, and Manchuria. By 1941, Japanese command in Manchukuo, North China, and headquarters in Tokyo had devised a strategic sequence for administration of effective hearts and minds counterinsurgency. Now there were labels for what was done: jinshin antei (stabilizing human feelings); jinshin shūran (capturing the public heart); jinshin hāku (grasping the human heart); minshin kakutoku (possessing the people’s sentiment); minshin kakuho (ensuring the people’s feelings); (minshin hāku) seizing the people’s hearts); minsei antei (stabilizing civilians) and minsei iji (maintaining civilian life). The army set out a sequence for all seized and stabilized hearts programs. First, a thorough assessment of security and risk was to be made. Second, there was to be development of economic resources and parallel restoration and/or development of communications and transport. According to Japanese counterinsurgency theorists, stabilizing local security, economics, and communications opened the hearts of subjugated peoples, making it possible to seize them for the Empire.25 Methods varied, but the general sequence was clearing local spaces, holding them, protecting their populations, and administering the suasions of modernity through securing the supplies farmers needed to farm and live, making investments in rural community improvements, working through local leaders, and training and education in the basic principles of Japanese imperial theory.26 Other seized hearts tactics included protection of local religious beliefs and practices, respect for local customs, enforcing price stability, creating employment, developing roads, ports, and airports, and recalibrating both justice and education systems so that they worked for the Empire rather than against it.27 The threat of state violence hung over it all; fear was the precursor of effective hearts and minds counterinsurgency then, as it is now.

By 1938, possibly earlier, seized hearts tactics constituted a core principle of Imperial Japanese Army operations in conquered territory, although inconsistently and unevenly applied. As Iwatani Nobu notes, even in the protracted, grim war over control of North China between 1937 and 1945, the military were well aware of the virtues of moving from Three All scorched earth strategy to seized hearts hold and protect, hearts and minds work on local communities.28 When the Guomindang command deliberately breached the levees and dykes of the Yellow River in north central China in 1938, setting off a catastrophe to impede the Japanese advance on Wuhan, Japanese military command in Japanese-controlled areas flooded by the now-unfettered river recognized immediately that the misery of the millions of peasants flooded off their lands would exacerbate anti-Japanese feelings. Accordingly, the regional Imperial Japanese Army administration harnessed Chinese officials to set up programs to recruit labor and supply materials for urgent reconstruction of levees and for flood abatement.29 There were also efforts to reproduce a specialized version of the village protection system so widely applied in Manchukuo in North China. Hoping to counter attacks on the railroads running between coastal and hinterland centers to Beijing, Japanese military command had a number of fortified villages built and populated along the lines. Chinese from adjacent districts were forced into these places, supplied with some light arms, some training, then charged with defense and repair of the railroad. The project was unsuccessful. Attacks did not decline; repairs were not done more expeditiously. Eighth Route Army guerrilla units continued to operate with relative impunity and with the support of most Chinese.30 In the end, seized hearts programs in North China were partial and unsuccessful. Much of rural north China was never cleared of armed resistance organized by both Communist and Guomindang forces. Without clearance, seized hearts was not possible and, what is more, seized hearts counterinsurgency programs required time and resources not available to Japan in the middle of a grueling war fought in Chinese territory with dwindling materiel and supplies.

In Malaya between 1942 and 1945, however, seized hearts counterinsurgency was more successful. The Southern Army which invaded and conquered Southeast Asia included many veterans of conquest and colonization in Manchuria and North China. Some of these men came to the management of Burma, the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaya and Singapore with previous experience in delivery of seized hearts counterinsurgency as well as commitment to the approach. After Japan’s 1945 defeat, Iida Shōjirō, who had been Chief of Staff of the 4th Division of the Imperial Japanese Army in Manchukuo from 1935 to 1937, and commander of the 15th Army during its invasion of British Burma in 1942 remarked, “I believe that grasping the people’s hearts and minds is the greatest source of force . . . if the people’s hearts are detached, the goals of military policy cannot be realized.”31 Seized hearts counterinsurgency in Iida’s own Southeast Asia bailiwick of Burma was, however, almost unnecessary beyond the regions where Burma and India ran together and the British and Japanese militaries faced each other. In the rest of Burma, the Burman majority was mostly pro-Japanese, the Shan minority swore an oath of fealty to the Empire of Japan in exchange for being left to manage its own affairs, and other minorities tended to seek Japanese protection against the Burman majority. Any real insurgency in Burma was directed against British rule; Iida later used these anti-British insurgents in the military campaigns against the British at Imphal and Kohima in 1944.32 In the Philippines, the military government made a start at seized hearts counterinsurgency, clearing some zones and setting up neighborhood associations to police the “peace”, but the program appears to have gone no further than this even though the Japanese imperial state in the Philippines faced a powerful insurgency.33

In some contrast, the Japanese military governments, Japanese civil administrations, and local elites in peninsular Malaya delivered an almost complete seized hearts sequence. Just a couple of weeks after the Japanese invasion force landed on the beaches at Kota Bharu on December 8, 1941, the Southern Army set up an initial command station at Alor Setar in the northwest of the Malay Peninsula. According to the military historian, Tachikawa Kyōichi, it was here that the military government began planning for seized hearts counterinsurgency in Malay and Singapore.34 Military intelligence for the invasion and government of the two new colonies had identified the large Chinese communities in Malaya and Singapore as the most important threat to Japanese rule. Almost as soon as conquest was completed with the British surrender at the Ford Factory in Bukit Timah on February 15, 1942, the Japanese military turned to clearance of the identified threat. Japanese military governments in Singapore and the Malayan states issued directives ordering all Chinese males between the ages of 18 and 50 to report to designated screening centers for inspection: sook ching. Those who failed the inspection were taken out and killed. In Singapore alone, somewhere between 5 and 50 thousand died.35 Many more thousands were killed in the towns and cities of peninsular Malaya and in North Borneo.36 The sook ching roundups and killings were a form of seized hearts clearance, ridding designated zones of threat and potential threat while making the consequences of refusal to submit to Japanese rule clear. Expropriation of Chinese businesses and a punishing financial extortion were then deployed to force the local Chinese elite into cooperation with the new imperial regime.

That cooperation included planning, funding and organization of protection villages and removal of Chinese into them as a tactic to prevent support of an armed anti-Japanese insurgency mounted by the mostly Chinese Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army. In less than three years between 1942 and 1945, the imperial Japanese state had at least 30 protection villages built in Malaya and forced hundreds of thousands of Chinese to move into them.37 Relocation to protection villages was sometimes promoted to local Chinese as voluntary, but in application, it was usually compulsory. At times, the Japanese military and Malay paramilitary used savage methods to stamp out resistance to moving: when Chinese residents of the town of Kuala Kubu Baru declined to move to a new protection village several kilometers from the town itself, the Japanese military, assisted by Malay police, burned down an entire neighborhood in the town and threatened violence until the Kuala Kubu Baru Chinese moved.38 Most protection villages in Malaya were fenced; some were fortified. Residents needed passes to get in or out. Moral and ideological retraining went on within the villages. At the New Syonan protection village north of Mersing, Shinozaki Mamoru, a civilian administrator from Singapore, visited regularly to preach the doctrine of Pan-Asianism to the 12,000 Singapore Chinese residents. Lands around the villages were methodically cleared of insurgents and proclaimed as model peace zones.39 Cut off from the Chinese community and its tangible and political succor, insurgents in Malaya and Singapore had to resort to banditry for food. Their already sketchy military resources went into to survival rather than guerrilla campaigns against Japanese forces. The Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army did not disappear because of Japan’s seized hearts strategy, but its inability to harry Japanese garrisons and obstruct Japanese rule must be understood in part as a product of seized hearts counterinsurgency. There is no evidence to suggest that Chinese in Japan’s Malayan protection villages felt any loyalty to Japan and its reign in Malaya. They did, however, submit to the programs that kept them from supporting insurgency. For the managers of the Japanese state that was good enough.

Hearts and Minds

In 1948, the British Empire faced an armed Communist insurgency in Malaya: Darurat Malaya or Malayan Emergency. Both the rebellion and the British strategy for countering it bore some similarities to the wartime Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army insurgency of 1942-1945 and imperial Japanese seized hearts counterinsurgency. Remnants of the Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army regrouped and reorganized as the Malayan National Liberation Army with a mission to attack British colonialism in Malaya and to prevent eventual independence from total domination by the Malaya majority. After approximately two years of violent but ineffective attempts to put down the insurgency, the British adopted clear, hold, protect, and persuade strategy aimed directly at the Chinese population who were removed to fortified “New Villages” where British managers of the British Empire in Malaya and their Malay cohort subjected them to political proselytization, self-policing, and reward for compliance with some of the social and economic goods of modernity, especially schools, health care, safety, and support for small business.40 By 1958, more than 763,000 Chinese-Malayans (12 percent of the total Malaya population) lived in 582 fortified and heavily controlled protection villages.41 The program was devised by General Sir Harold Briggs and implemented by General Gerald Templer.

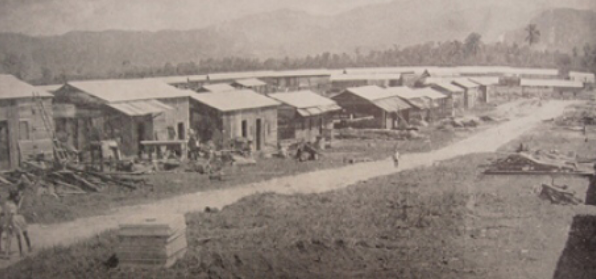

Jinjang New Village, Malaya, 1950s. Source: Aliran.com

The similarities between the population control elements of imperial Japanese seized hearts counterinsurgency in Manchukuo and Malaya before 1945 and British counterinsurgency tactics in Malaya between 1948 and 1960 are so striking, and the absence of such tactics in western counterinsurgency before 1948 and Malaya is so remarkable, it is hard not to posit some recurrence of the Empire of Japan in them, some British awareness of Japanese seized hearts tactics taken up and applied in Malaya in the 1950s. Yet, even though the Guomindang Chinese legation in Malaya complained to the British authorities that security forces were using Japanese tactics to control Chinese civilians,42 the lineage is hard to substantiate. We have no archival insight into the origins of General Briggs’s thinking since his papers appear to have disappeared in Cyprus where he retired after designing the hearts and minds counterinsurgency plan for Malaya. Additionally, when the historian of counterinsurgency, Thomas Mockaitis, conducted several in-depth interviews with Gerard Templer, Japan’s counterinsurgency tactics in northeast China and Southeast Asia never came up.43 Even so, it is almost inconceivable that Briggs and his advisors in Singapore and Kuala Lumpur went into counterinsurgency planning ignorant of the “soft” tactics used by Japan in Manchukuo and Malaya; they were certainly aware of the “hard” Three-Alls tactic the Imperial Japanese Army used to suppress resistance prior to holding, protecting, and persuading. English language reportage and scholarship described and analyzed Japanese counterinsurgency in Manchukuo in the late 1930s, notably in Far Eastern Survey, the research and reportage organ of the Institute of Pacific Relations, a non-government organization in the Wilsonian internationalist mode based in Honolulu and New York.44 During the years when Japan controlled Singapore and Malaya, the protection villages were frequent topics of reports in the English language newspapers published in Singapore (Syonan Shimbun), in Ipoh (Perak Times), and Georgetown (Penang Shimbun). The people of Singapore and the Malayan towns and cities were also very much aware of Japan’s seized hearts counterinsurgency methods. British intelligence collected information about all Japanese operations in the area. For example, in 1943, agents of the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) infiltrated Malaya and over the course of several secret meetings with representatives of the Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army in 1943 and 1944, collected comprehensive intelligence about imperial Japanese counterinsurgency strategies, including evidence that seized hearts tactics were effective in countering the activities of the Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army. SOE intelligence on Japanese operations in Malaya then went to British South East Asia Command, to London and New Delhi, and was available to the British after they re-occupied Singapore and Malaya.45

Security gates at a New Village, 1950s, Malaya. Source: Aliran.com

British awareness of Japanese colonial operations did not end after Japan’s defeat in 1945. Indeed, the success of Britain’s recolonization of Singapore and Malaya relied heavily on advice from, and consultation with, Japanese military and civilian administrators awaiting repatriation to Japan, Korea and Taiwan in Singapore and Malaya between late 1945 and the middle of 1947, by which time most had gone home.46 Shinozaki Mamoru, who had helped set up at least three protection villages and had preached the virtues of Pan-Asianism to the residents of the New Syonan protection village near Mersing, was a senior advisor to the British authorities after their return to Singapore. British military lawyers and intelligence officials also debriefed more than 12,000 Japanese officers, NCOs, enlisted men, kempeitai military police, and Japanese, Korean and Taiwanese gunzoku auxiliary military personnel stationed in Singapore and Malaya at the time of the surrender. Conducted by British personnel hastily trained to speak Japanese at the School for Oriental and Asian Studies in London and by Japanese-Britons and Japanese-Australians, interrogations ranged widely across Japan’s conduct, methods, and policies in Malaya and Singapore.47 It should not be surprising then, to happen upon elements of Japanese seized hearts counterinsurgency in the subsoil of British counterinsurgency in Malaya. An early 1950s Xinhua news feed reported that Chinese-Malayans deported to Beijing by the British as another counterinsurgency measure remarked in interviews that the British modeled the New Village program on the Japanese protection village program.48 A 1958 document from the British colonial forestry department in Malaya mentions that Japanese protection villages in Malaya served as models for the British New Villages, and later scholarship reworking the department of forestry mention calls the imperial Japanese protection villages “prototypes” of the British counterinsurgency program.49 A number of Japanese protection villages were “repurposed” as British New Villages. For example, the previously mentioned Japanese protection village outside Kuala Kubu Baru became a New Village after 1950. The British also turned Kampong Hubong, which had been the large New Syonan protection village for Singapore Chinese before 1945, into a New Village with a population of many thousands.50

The British considered their clear, hold, protect, and persuade hearts and minds counterinsurgency program in Malaya a success: the Malayan National Liberation Army was cut off from its core constituency and, although the Chinese in New Villages still worried about their future in an independent state run by Malays, the goods of modernity supplied to them in exchange for their cooperation turned them against the Communist rebellion: good enough.

After merdeka in 1957 and final creation of Malaysia (without Singapore) in 1959, the Malay managers of the new state also thought so highly of the New Village program that they recreated elements of it as a way of regulating Malaysia and making it more legible as a modern state. Until its conversion into a state manager of agribusiness in 1991, the Federal Land Development Authority (FELDA) created, administered and managed a vast relocation and resettlement scheme in peninsular Malaysia.

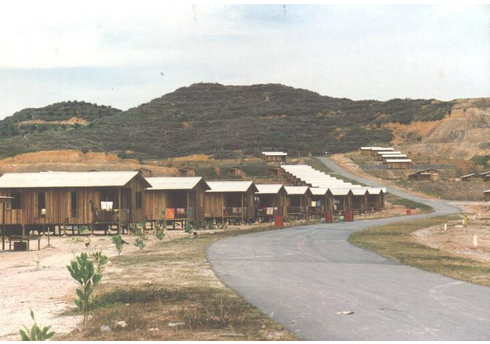

A FELDA resettlement village, Pahang, Malaysia 1970s

Source: Dato Faizoull Ahmad, LiDAR Remote Sensing: FELDA’s Experiences in Developing Plantation and Community. Presentation. Asia Geospatial Forum, Jakarta, 2014.

The lineage of the FELDA program reaches back to British New Villages counterinsurgency, to imperial Japanese protection villages in Malaya and Manchukuo, to the Japanese resettlements of First Peoples in Taiwan and Hokkaido, and beyond there, to the relocations and resettlements of Native Americans in the United States after the Indian Removal Act of 1830, for Orang Asli, Malaysia First People, were among the initial communities to be moved and resettled by FELDA.51 The other people relocated and resettled in modern villages were landless Malays.52 FELDA relocations aimed to isolate Orang Asli from the conditions of their indigeneity, which the state found difficult to read as anything other than a challenge to its existence, and once resettled, to transform them into modern Malaysian citizens. The radical mobility and provisional terms of life prevailing in the large landless Malay community was at odds with the modernizing mission of the Malaysian state, and this necessitated FELDA relocation in and of it itself, but it was the perceived susceptibility of landless Malays to anti-state messages that really troubled state managers in Kuala Lumpur and the provincial capitals. The FELDA relocation and resettlement program was always couched in terms of the benefits and goods of modernization for people – health, hygiene, housing, education, infrastructure, safety – but the insurgencies of local Chinese against Japanese rule and against British rule along with the tactics used to counter them were still fresh in the thinking of the managers of the Malaysian state and FELDA. James Scott has noted that FELDA settlements thus had some of the characteristics of New Villages.53 This means that they also resembled Japanese protection villages. They were set out in a basic grid pattern, houses and lots were numbered consecutively. Residents were carefully chosen. Estimates were made of their likely loyalty to the state. They were registered, carried identity cards, lived beneath constant surveillance, and ingress and egress from the villages were monitored. FELDA resettlement existed to produce submission to the Malaysian state.54

Elements of Japanese seized hearts methods also recurred in South Vietnamese counterinsurgency in the 1950s and 1960s. In 1961, British managers of the counterinsurgency system in Malaya went to Saigon to consult with President Ngô Đình Diệm on hearts and minds tactics against insurgency in the Republic of Vietnam. From this visit and the subsequent British advisory mission to Sai Gon, several historians have concluded that South Vietnamese hearts and minds counterinsurgency, which included clearance, hold, protection, and persuasion of population relocated into new fortified villages, known now as strategic hamlets, was a direct descendant of British hearts and minds counterinsurgency in Malaya. However, President Diệm and his senior advisors had their own ideas about hearts and minds counterinsurgency well before the British mission arrived in Sai Gon.55 There is reason to think that Diệm was probably aware of Japanese seized hearts counterinsurgency well before he became prime minister of the State of Vietnam in 1954 and then president of the Republic of Vietnam in 1955. As a nationalist and anti-Communist, Diệm felt a sense of alliance with some of the political elements of the Imperial Japanese Army and Japanese diplomatic mission in French Indochina in the early 1940s, men who were vigorously opposed to Communism, committed to some form of independence for Vietnam, and under orders to persuade Vietnamese to cooperate with the Empire of Japan.56

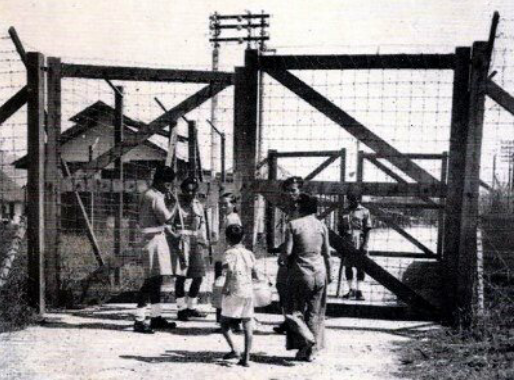

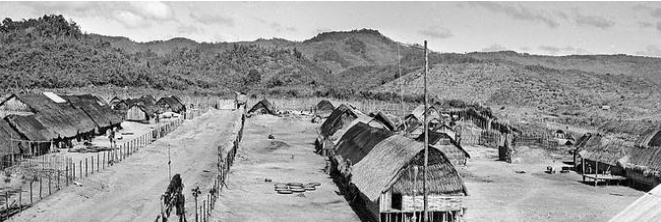

Strategic Hamlet, Vung Tau District, Republic of Vietnam, 1961

Source: Wolfgang Wiggers

Diệm was also connected to yasu butai (Yasutai), a Japanese counterinsurgency and secret operations unit in French Indochina. The senior officers of Yasutai possessed considerable applied or theoretical experience in counterinsurgency operations; the junior officers came to Vietnam fresh from intensive training in seized hearts and guerilla warfare methods at the new Futamata branch of the Military Army Nakano School in Tokyo.57 The highly experienced operative and chief of the southern arm of Yasutai, Ishida Shōichi, was close to Diệm, and saved him from certain arrest by the French security forces in 1944, then transported him to Sai Gon where he lived under the protection of local Yasutai and Japanese diplomats.58 Although Yasutai was broken up after the Japanese defeat by the Vichy French regime in Indochina in early 1945, some members remained in Vietnam where they explored ways of administering seized hearts methods to the population in preparation for independence in the face of impending invasion by the British.59 By the time he became President, Diệm was also certainly aware of futile French attempts to fight Viet Minh rebellion in Tonkin through relocation and resettlement of peasants and the British hearts and minds counterinsurgency in nearby Malaya, which he discussed with Malay nationalist, Tunku Abdul Rahman, in the mid-1950s.60

As head of state, one of Diệm’s first assessments of the South Vietnam security situation evoked both Japanese seized hearts counterinsurgency and the British approach in Malaya. He identified rural communities as disaffected and vulnerable to the persuasions of the Viet Minh insurgents. He saw the solution as military clearance of identified zones and hold and protection of the cleared zones through resettlement into fortified villages where administration of the goods of modernity along with ideological persuasion were to be administered to residents. Diệm began with clearance, relocation, and resettlement of the hill peoples of Vietnam: Hmong; Tay; Red Dao; Giay. Next he began forcing existing communities in the rural areas of the Mekong Delta to police their own loyalty to the South Vietnam state through surveillance and denunciation.61 Finally, in 1959 the government of the Republic of Vietnam began relocating and resettling peasants into newly-built, purpose-designed, fortified villages of up to 10,000 residents: strategic hamlets. Small groups of peasants living in remote and isolated conditions were agglomerated with similar small groups into fortified villages of about 1,500 residents.62 Diệm then approached the British official, Gerald Templer, about details of the Malayan New Village program, though it is not clear that he followed Templer’s suggestions.63 By 1963, around 4.3 million people had been moved into thousands of strategic hamlets, all of which had their own armed security forces, fortifications, strict ingress and egress procedures, heavy surveillance, elements of modern infrastructure and services, and regular education in the virtues of the South Vietnam state.64 The outcomes, however, were not good enough. The Viet Minh outwitted Sai Gon and its hearts and minds counterinsurgency again and again; the Communist message and what it promised appealed to more people.65

The failure of hearts and minds counterinsurgency in Diệm’s South Vietnam using the clear, hold, protect, and persuade sequence did not mean that the strategy disappeared, however. Rather, it went on in revised forms in Vietnam and beyond. This persistence of the strategy beyond South Vietnam and beyond the Vietnam War indicates that something of the imperial Japanese seized hearts strategy persisted . Clear, hold, protect, and persuade counterinsurgency tactics are now key weapons in the global counterinsurgency arsenal. In 1954, the CIA sponsored a military coup in Guatemala to reverse land reforms put in place by a democratically elected government. For more than 30 years, the Guatemalan military, funded and tutored by the United States in clear, hold, protect, control and persuade counterinsurgency tactics, waged a vicious war against insurgents. Seized hearts style population relocation, control, and modernization destroyed and remade village life.66 The Guatemalan military incinerated more than 600 Mayan villages and small towns and murdered or incarcerated any villagers suspected of sympathies with the insurgents.67 Then funds and technology supplied by CIA and the United States Agency for International Development were turned to construction of new secured villages, population relocation, and delivery of modern infrastructure and services to residents. By 1984 there were 24 “protection” villages in Mayan Guatemala with another 55 planned.68 Colonel Mario Enrique Paiz Bolanos told the Washington Post that population relocation, concentration and control were meant only to supply what Mayans lacked: security and development, but he also read from the Guatemalan Manual for Counterinsurgency: “Counter-subversive war is total, permanent and universal, and it requires the massive participation of the population like the subversive war it confronts … our objective is the population.”69 Bolanos could have been speaking from Kwantung Army guides to seized hearts counterinsurgency in Manchukuo; he could have been echoing a British speech upon the opening of another New Village in Malaya, recycling Diem’s speeches and media releases upon the need for strategic hamlets in South Vietnam. Bolanos could have been paraphrasing operational materials for counterinsurgency in El Salvador during the regime of Anastasio Somoza,70 parsing almost any United States military manual for counterinsurgency operations in Iraq after the big surge war strategy of 2003,71 in Afghanistan in 2018 where the United States’ military was enjoined to separate the population from Taliban and other insurgent organizations by relocation and concentration behind walls, fences and “other means”.72

Concluding remarks

Late 20th and early 21st century administrations of hearts and minds counterinsurgency descended from the clearance, hold, protect, and persuade principles of imperial Japanese seized hearts strategy constitute a type of perdurance. The temporal parts of Japanese hearts and minds counterinsurgency have persisted into a future beyond destruction and disappearance of the spatial parts; they perdure. The Japanese protection villages of Manchukuo and colonized Malaya may be gone now, but the ideas about power, modernity, and defense of the state that formed these spaces in the past persist (or recur) across other temporalities in which they contour other spaces in both new and old ways. Because they persist intact, perduring legacies of colonialism have unique properties unavailable in other types of colonial legacy: they act in the present as they acted in the past. As Joyce Lebra showed many years ago, the temporal remains of imperial Japanese militarism in the Republic of Indonesia recurred as a form of militarism there that bore uncanny resemblance to imperial Japanese militarism before 1945.73 Several other imperial Japanese formations also perdure, not least cadastral surveys and private ownership of land in the island states of Micronesia and the accumulation of Japanese wealth and status based on trade in and display of Korean, Chinese, and Mongolian heritage looted between the 1890s and 1940s. What distinguishes the persistence of imperial Japanese seized hearts counterinsurgency methods in the postwar and beyond is geographical passage of the perduring formation beyond Japan and its former colonies into the strategies of the world’s greatest military power, its allies and client states. That is a testament to the tactical brilliance of Japanese counterinsurgency and to the ubiquity of small wars which, according to Max Boot, have been the most common form of warfare since the Great Revolt of Jews against Roman rule beginning in the 7th century.74

Notes

Meet the Press transcript for August 15, 2010. Transcripts on Meet the Press. NBCNews.com. http://www.nbcnews.com/id/38686033/ns/meet_the_press-transcripts/t/meet-press-transcript-august/#.Xhj-zy2B3oc Viewed January 11, 2020.

See for example, Robert Egnell, “Winning ‘Hearts and Minds’? A Critical Analysis of Counter-Insurgency Operations in Afghanistan.” Civil Wars, 2010, Vol. 12, No. 3, pp. 282-303.

Christian Tripodi, “’Good for One but Not the Other’: the ‘Sandeman System’ of pacification as applied to Baluchistan and the North-West Frontier, 1877-1947.” The Journal of Military History, Vol. 73, No. 3, 2009, pp. 767-802.

Moshe Gershovich, French Military Rule in Morocco: Colonialism and its Consequences. (London and New York: Routledge, 1999); Michael P. M. Finch, A Progressive Occupation? The Gallieni-Lyautey Method and colonial pacification in Tonkin and Madagascar, 1885-1900. (Oxford and London: Oxford University Press, 2013). Kim Munholland, “’Collaboration Strategy’ and the French Pacification of Tonkin, 1885-1897.” The Historical Journal, Vol. 24, No. 3, 1981, pp. 629-650.

Mark Selden, China in Revolution: The Yenan Way Revisited. (London and New York: Routledge, 1995), ff. 1, p. 166. The 1995 volume is a revised, critical edition of a 1971 publication in which the same footnote occurs.

James C. Scott, Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998).

See: David Galula, Counterinsurgency Warfare: Theory and Practice. (New York: Praeger 1964); Robert G. K. Thompson, Defeating Communist Insurgency: The Lessons of Malaya and Vietnam (New York: Praeger 1966); Anthony James Jones, Resisting Rebellion: The History and Politics of Counterinsurgency. (Lexington: Univ. Press of Kentucky 2004), Bard O’Neill, Insurgency and Terrorism: From Revolution to Apocalypse, 2nd ed. (Washington DC: Potomac Books 2005). Michael Fitzsimmons, “Hard Hearts and Open Minds? Governance, Identity and the Intellectual Foundations of Counterinsurgency Strategy.” The Journal of Strategic Studies. Vol. 31, No. 3, June 2008, pp. 337 – 365.

Fujita Fumiko, American Pioneers and the Japanese Frontier: American Experts in Nineteenth-Century Japan. (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1994).

Michele M. Mason, Dominant Narratives of Colonial Hokkaido and Imperial Japan: Envisioning the Periphery and the Modern Nation-State. (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012).

Paul Barclay, Outcasts of Empire: Japan’s rule on Taiwan’s “Savage Border,” 1874-1945. (Oakland: University of California Press, 2017). Alliance of Taiwan Aborigines, Report of the Alliance of Taiwan Aborigines to the United Nations Working Group on Indigenous Populations, August 1993. www.taiwandocuments.org/ata.htm Retrieved August 21, 2017.

Tetsudō aigoson gaisetsu [General explanation of railway protection villages], National Institute for Defense Studies, Army General Records, China Incident, Reference Code C11110457900, Japan Center for Asian Historical Records.

Robert A. Scalapino and Chong-Sik Lee, Communism in Korea: Part I: The Movement, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1972).

Shin Gi-Wook, “Defensive Struggles or Forward-looking Efforts? Tenancy Disputes in Colonial Korea, 1920- 1932.” The Journal of Korean Studies, Vol. 7, 1990, pp. 3-33.

Charles K. Armstrong, “Centering the Periphery: Manchurian exile(s) and the North Korean state.” Korean Studies, Vol.19, 1995, pp. 1-16.

Erik W. Esselstrom, “Japanese police and Korean resistance in prewar China: The problem of Legal Legitimacy and Local Collaboration.” Intelligence and National Security, Vol. 21, No. 3, 2006, pp. 342-363.

Mo Tian, “Japanese Rule Over Rural Manchukuo: Strategies and Policies.” Doctoral thesis, Australian National University, September 2015.

Masataka Endō, “Manshūkoku tōchi ni okeru hokō seido no rinen to jittai ‘minzoku kyōwa’ to hōchi kokka to iu futatsu no kokuze wo megutte,” Ajia Taiheiyō Kenkyū, No. 20, February 2013, pp. 37-51.

Chong-Sik Lee, Counterinsurgency in Manchuria: The Japanese Experience, 1931-1940, Memorandum RM-5012-ARPA January 1967, Rand Corporation. Is it not the case that all his books list the author as Chong-Sik Lee.

Erik W. Esselstrom, “Rethinking the Colonial Conquest of Manchuria: The Japanese Consular Police in Jiandao, 1990-1937.” Modern Asian Studies, Vol. 39, No. 1, 2005, pp. 39-75.

Piao Renzhe, ‘Manshū’ ni okeru Chōsenjin ‘Anzen nōson’ ni kansuru ikkōsatsu [A study of Korean protection villages in Manchuria], Hokkaidō University Graduate School of Education Research Bulletin, Vol. 106, pp. 103-117, and Chong-Sik Lee, op. cit.

Tachikawa Kyōichi, Nanpō gunsei ni okeru minshin anteisaku [Stability of the people’s hearts policy in the Southern Army], NIDS Military History Studies Annual, National Institute of Defense Studies (Japan), No. 19, March 2016, pp. 17-44.

Asada Kyōji, Nippon teikokushugi ni yoru Chūgoku nōgyō shigen no shūdatsu katei (1937-1941nen) [Exploitation of Chinese farming resources under Japanese imperialism, 1937 to 1941], Journal of the Faculty of Economics of Komazawa University, Vol. 36, March 1978, pp. 1-74.

Iwatani Nobu, “Japanese Counterinsurgency Operations in North China.” NIDS Military History Studies Annual, Vol. 19, March 2016, pp. 1-16.

Micah S. Muscolino, The Ecology of War in China: Henan Province, the Yellow River, and Beyond, 1938–1950. (Studies in Environment and History), (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015).

George E. Taylor, The Struggle for North China. (New York: Institute of Pacific Relations, 1940). Dagfinn Gatu. Village China at War: The Impact of Resistance to Japan, 1937-1945. (Copenhagen: Nordic Institute of Asian Studies, 2007).

Iida Shōjirō, Biruma gunsei to dokuritsu mondai wo kaikoshite (shuki) [Recollecting the Japanese military administration of Burma and the problem of independence (Note)], February 1962, National Institute of Defense Studies, War History Research Center Depository. Quoted in Tachikawa Kyōichi, op. cit., p. 21.

Andrew Selth, “Race and Resistance in Burma, 1942-1945.” Modern Asian Studies, Vol. 20, No. 3, 1986, pp. 483-507.

Teodoro A. Agoncillo, The Fateful Years: Japan’s Adventure in the Philippines, 1941-1945. Volume 1. (Manila: The University of the Philippines Press, 1965, 2010).

Hayashi Hirofumi, “The Battle of Singapore, the Massacre of Chinese and Understanding of the Issue in Postwar Japan.” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 28-5-09, July 13, 2009. https://apjjf.org/-Hayashi-Hirofumi/3187/article.html Viewed January 12, 2020.

Geoffrey C. Gunn, “Remembering the Southeast Asian Chinese Massacres of 1941-1945.” Journal of Contemporary Asia, Vol. 3, No. 8, 2007, pp. 273-291.

Hara Fujio, “The Japanese Occupation of Malaya and the Chinese Community.” Paul Kratoska, editor, Malaya and Singapore During the Japanese Occupation. (Singapore: Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 1995).

Leon Comber, Malaya’s Secret Police 1945-60: The Role of the Special Branch in the Malayan Emergency. Monash Papers on Southeast Asia, (Melbourne: Monash Asia Institute, 2008).

Benjamin Grob-Fitzgibbon, “Counterinsurgency, the Interagency Process, and Malaya: The British experience.” Kendall D. Gott and Michael G. Brooks, editors, The US Army and the Interagency Process: Historical Perspectives. The Proceedings of the Combat Studies Institute 2008 Military History Symposium. (Fort Leavenworth, Kansas: Combat Studies Institute Press, 2008), pp. 93-104.

Karl Hack, “Detention, Deportation and Resettlement: British Counterinsurgency and Malaya’s Rural Chinese, 1948–60.” The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, Vol. 43, No. 4, 2015, pp. 611-640.

See for example, John R. Stewart, “Protected and Railway Villages in Manchuria.” Far Eastern Survey, Vol. 8, No. 5, Mar. 1, 1939.

Rebecca Kenneison, “The Special Operations Executive in Malaya: Impact and Repercussions, 1941-48.” Ph.D. thesis, University of Essex, 2017.

See for example, Akashi Yōji. Nihon no Eiryō Maraya Shingapōru senryō 1941-45 nen: Intabyū kiroku (Nanpō gunsei kankei shiryō), (Tokyo: Ryukei shōsha, 1998).

Masuda Hiroshi, Nipponkōfukugo ni okeru nanpōgun no fukuin katei, 1945-1948 [Demobilizing the Southern Army after Japan’s Surrender, 1945-1948], Gendaishi kenkyū, No. 9, March 2013, pp. 1-159.

A. B. Walton, “Malayan forests during and after the Japanese occupation.” Director of Forestry, National Archives of Malaysia, DF -58-45. The ‘prototype’ paraphrase of Walton’s report is in T. N. Harper, The End of Empire and the Making of Malaya., (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001,) p. 37.

“Mersing Kechil emphasises close ties.”, MYsinchew.com, September 27, 2014. Originally at Sin Chew Daily www.sinchew.com.my Translation of online version by Soong Phui Jee. www.mysinchew.com/node/101829 Viewed November 28, 2016. Ong Sze Teng, Tan Shou Ping, and Tan Wan Ting. UTAR Xincun shequ xiangmu baogao: haowangcun roufu [UTAR New Village Community Project Report: Kampong Hubong, Johor], Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman, November 2013.

Aliyu Salisu Barau and Ismail Said, “From Goodwill to Good Deals: FELDA Land Resettlement Scheme and the Ascendancy of the Landless Poor in Malaysia.” Land Use Policy, Vol. 54, (July 2016), pp. 423-431.

Wolf Mendel, editor. Japan and South East Asia: From the Meiji Restoration to 1945, Volume 1. (London and New York: Routledge, 2002).

Kiyoko Kurusu Nitz, “Independence without Nationalists? The Japanese and Vietnamese Nationalism during the Japanese period, 1940-45.” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 15, No.1, (1984), pp. 108-133.

Tachikawa Kyōichi, “Yasu-Butai: The Covert Special Unit of the Japanese Army behind the Coup de Force of March 9, 1945.” Masaya Shiraishi, Nguyễn Văn Khánh, and Bruce M. Lockhart, editors. Vietnam-Indochina-Japan Relations during the Second World War: Documents and Interpretations. (Tokyo: Waseda University Institute of Asia-Pacific Studies [WIAPS]), February 2017.

Tachikawa Kyōichi, “Independence Movement in Vietnam and Japan during WWII.” NIDS Security Reports. No. 5, (2000). www.nids.mod.go.jp/english/publication/kiyo/pdf/bulletin_e2000_5.pdf Accessed January 20, 2020. Also, Seigō Kaneko, “Annam Himitsu butai: Annam dokuritsu ni karamaru yasutai no anryaku” [The Annam Secret Unit: The Secret Maneuvers of the Yasutai in the Independence of Annam], Shukan Yomiuri, special edition: “Nippon himitsu sen” [Japan’s Secret Wars], 8 Dec. 1957.

Paul Cheeseright, “Involvement Without Engagement: The British Advisory Mission in South Vietnam, 16 September 1961–31 March 1965.” Asian Affairs, Vol. 42, No. 2, (2011), pp. 261-275.

Geoffrey C. Stewart, “Hearts, Minds and Công Dân Vụ: The Special Commissariat for Civic Action and Nation-Building in Ngô Đình Diệm’s Vietnam, 1955–1957.” Journal of Vietnamese Studies Vol. 6, No. 3 (2011), pp. 44-100.

Dispatch 426: Durbrow to State Department, 6 June 1960. National Archive of the United States, College Park: Central Files, 751k.00/6-660).

Peter Busch, “Killing the ‘Vietcong’: The British Advisory Mission and the Strategic Hamlet Programme.” Journal of Strategic Studies, Vol. 25, No. 1, (2002), pp. 135-162.

Philip E. Catton. “Counter-Insurgency and Nation Building: The Strategic Hamlet Programme in South Vietnam, 1961–1963.” The International History Review, Vol. 21, No. 4, (1999), pp. 918-940

Douglas Farah, “Papers Show U.S. Role in Guatemalan Abuses.” Washington Post,

Thursday, March 11, 1999, p. A26.

Megan Ybarra, “Taming the Jungle, Saving the Maya Forest: Sedimented counterinsurgency practices in contemporary Guatemalan conservation.” The Journal of Peasant Studies, Vol. 39: No. 2, 2012, pp. 479-502.

David H. Ucko, “Counterinsurgency in El Salvador: The lessons and limits of the indirect approach.” Small Wars & Insurgencies, 2013, Vol. 24, no. 4, pp. 669-695

United States Government, Department of the Army, Field Manual No.3-24, Marine Corps Warfighting Publication No. 3-33.5, Insurgencies and Countering Insurgencies. Washington, D.C., 2014, 10-6.

Joyce C. Lebra, Japanese-trained Armies in Southeast Asia. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1977).

Max Boot. Invisible Armies: An Epic History of Guerrilla Warfare from Ancient Times to the Present. (New York: Liveright Publishing. 2013).