Abstract: The dynamics of Japan’s indigenous rights struggles are not well understood, but the 2020 Tokyo games may spark serious debate on restoring and promoting the social, cultural, economic and political rights of the Ainu people. It appears that people from throughout Japan and the world curious about Ainu culture may be disappointed in the Olympic ceremonies and the new Upopoy National Ainu Museum and Park that opens in 2020. The Olympic moment offers an opportunity to embrace diversity, but probably will highlight the limits of the Japanese state’s willingness to recognise the rights of Ainu as indigenous people.

Singing Together: Visions of Olympic Harmony

In the modern era, Olympic games have always been opportunities for nations to make grand statements about identity. The games are a venue, not just for sporting prowess, but for symbolic representations of the way the nation would like to be seen (or, at least, the way its leaders would like it to be seen) by the rest of the world; and such identity statements have become ever more elaborate and spectacular with the passing of time (Tamaki 2019).

In the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, Japan presented itself to the world as a nation that had risen from the ashes of defeat in war to become an emerging economic and technological superpower. The gleaming new Shinkansen rail network and the flowing ultramodern lines of the Yoyogi Olympic stadium (designed by architect Tange Kenzō) spoke of a dynamic, forward-looking nation embarking on its ‘economic miracle’. In 2020, in the words of Olympic Organizing Committee CEO Mutō Toshiro, ‘the greatest keyword of the Olympics is kyōsei’ – a term meaning harmony, or (as it is sometimes translated in Olympic publicity) ‘unity in diversity’ (Sanyō Shimbun, 16 November 2019). This theme can be interpreted in many ways, but part of its purpose is clearly to counter criticisms, sometimes heard from domestic and international commentators, that Japanese society can be insular and slow to protect the rights of its ethnic and other minorities. As an aging Japan opens its doors to higher inflows of migrant workers, the term kyōsei has gained growing traction as a Japanese alternative to the internationally more familiar term ‘multiculturalism’.

Japan’s kyōsei will be on display throughout the year, not only in the Olympic ceremonies themselves, but also in surrounding events and venues, though the precise nature of this display has become a topic of some controversy. After early indications that traditional dances by the Ainu indigenous people would be included in the opening ceremony, the ceremony’s organizers announced that this would be impossible because of ‘time constraints’, but that Ainu would be present in some other form: ‘of course, it will be a ceremony where kyōsei with Ainu people will be brought into view’ (Hokkaidō Shimbun, 7 February 2020, evening edition). The most striking representation of this ‘kyōsei with Ainu people’ will take shape, not in the Olympic stadium itself but at the grand new Upopoy National Ainu Museum and Park, at Shiraoi in Hokkaido, which will open its doors to the public in late April 2020 – a date carefully chosen to ensure that it is ready to receive a flood of Olympic visitors to Japan (Kelly 2019). ‘Upopoy’ is an Ainu word meaning ‘singing in a large group’ – a vivid evocation of the theme of harmony – and the Museum and Park are known in Japanese as Minzoku Kyōsei Shōchō Kūkan: The Symbolic Space of Ethnic Harmony. Chief Cabinet Secretary Suga Yoshihide has expressed his hope that the site will attract one million visitors in a year: a prospect which has been strengthened by the decision to stage the Olympic marathon in the Hokkaido capital, Sapporo (Kaneko and Satō 2019).

For some, though, the creation of the new Museum and Park, at a cost of some US$220 million to date, raises problems about the underlying meaning of the harmony being celebrated at the 2020 Olympics (Kelly 2019; Nakamura 2019). Although the promotion of kyōsei, in this context, could become a milestone in greater recognition of Japan’s cultural and ethnic diversity, it also seems likely that the emphasis in the slogan ‘unity in diversity’ will fall on the word ‘unity’. In that case, recognition of diversity is likely to be limited to the ‘cosmetic multiculturalism’ of food, costume and festivals, without more substantial legal recognition of minority rights. These issues are particularly important and contentious ones for Japan’s Ainu community.

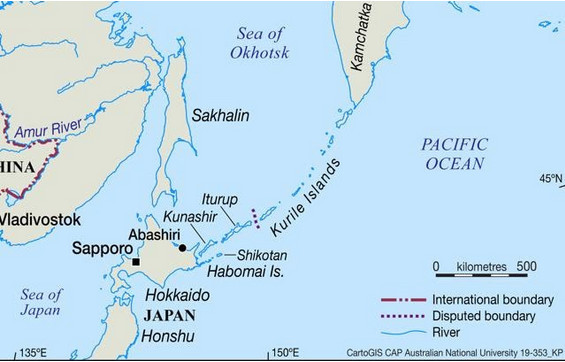

The Land of the Ainu (© CartoGIS CAP ANU)

Ainu History and the Japanese State

Until the middle of the nineteenth century, the Ainu people lived in self-governing village communities across a wide area stretching from the south of the island now known as Hokkaido to the middle of the island of Sakhalin and throughout the southern part of the Kurile Archipelago (now controlled by Russia). Some Ainu had even migrated as far as the mouth of the Amur River on the Asian mainland and the southern part of the Kamchatka Peninsula. In earlier times (until about the late eighteenth century), Ainu had also lived in the northern part of the main Japanese island of Honshu.

The various dialects of the Ainu language are completely different from Japanese, and Ainu people had their own economic, cultural and religious systems. Their economy was based largely on fishing and hunting, although in the warmer parts of Ainu territory they also grew small crops of grain and vegetables. Ainu society was connected by complex trade routes to the Japanese state in the south, China to the west and the expanding Russian empire to the north, as well as to other surrounding indigenous communities.

The production of richly appliquéd and embroidered robes is one of the hallmarks of Ainu material culture, past and present (Early 20th century photo, location and photographer unknown)

Long contact with Japan to the south meant that there was considerable intermarriage, and during the eighteenth century, the Japanese Domain of Matsumae, and later also the Japanese Shogunate, exerted growing economic control over Ainu fishing and trading activities. It was only after the Meiji Restoration of 1868, though, that most of the land of the Ainu was incorporated into Japanese territory, and that Hokkaido was given its present name and became a magnet for the migration of Japanese settlers. Ainu lands were seized by the Japanese state and turned into farmland, traditional Ainu hunting and fishing practices were prohibited, and Ainu children were subject to assimilationist education. An 1899 ‘Former Natives Protection Law’ attempted to impose assimilation throughout Ainu society, in practice resulting in the impoverishment and marginalization of many Ainu people (Kayano 1994; Siddle 1996). This law remained in place for almost a century. After Japan’s loss of its colony of Karafuto (in the southern half of Sakhalin Island) and the Kurile Islands, most surviving Ainu from these places had little option but to relocate to Hokkaido, leaving their ancestral homelands forever (Inoue 2016).

Because of intermarriage and the effects of long-lasting discrimination, it is difficult to say precisely how many Ainu people there are in Japan today. Hokkaido government surveys give a figure of around 24,000, but this is a substantial underestimate because some Ainu have migrated to other parts of Japan (including Tokyo), and some are reluctant to identify themselves as Ainu in public (Center for Ainu and Indigenous Studies 2010, 3). Against a background of rising indigenous rights movements worldwide, in 1984 the Utari Association of Hokkaido (Hokkaidō Utari Kyōkai, now known as the Ainu Association of Hokkaido) launched a campaign demanding the abolition of the antiquated ‘protection’ law and its replacement by a New Ainu Law which would recognize and promote Ainu culture, support education and economic self-reliance, restore fishing rights and create guaranteed seats for Ainu in parliament and the relevant local assemblies (see Siddle 1996, 196–200). The response of the government, though, was very limited. In 1997 the Former Natives Protection Law was repealed, but was replaced by an Ainu Cultural Promotion Law which focused only on traditional culture, without addressing any of the wider economic and political demands.

Campaigns by Ainu groups continued, and in August 2019 the Ainu Cultural Promotion law was in turn repealed and replaced with a new measure, generally referred to in the media as the ‘New Ainu Law’ (though its actual title is the much more cumbersome ‘Act on Promoting Measures to Realize a Society in Which the Pride of the Ainu People Is Respected’). But this again remains far more limited in scope than the new law proposed in 1984, and falls far short from the forms of indigenous rights recognition which have been enshrined in law in countries like Canada, Australia, New Zealand and Taiwan. The 2019 law continues to focus narrowly on culture – with the Upopoy National Ainu Museum and Park being its centrepiece – and grants Ainu permission to use traditional river, marine and forest resources only under the most restrictive conditions: for specific spiritual and cultural purposes where special license has been granted by the Japanese authorities. The result was a very mixed reaction from the Ainu community. While leaders of the Ainu Association of Hokkaido have expressed support for the law, widespread criticism has come from other community members, who have questioned both the lack of proper consultation during the drafting of the law and the new measure’s failure to recognise the rights of Ainu as indigenous people (Higashimura 2019; Shimizu, Hatakeyama, Maruyama and Ichikawa 2019; Morris-Suzuki, 2018).

The abbreviated consultation process and relatively hasty drafting of the law itself were driven by Olympic considerations. National media reports from early 2019 noted that the government was pushing to pass the law in the current session of parliament because of its ‘desire to present an appealing image of ethnic harmony [minzoku no kyōsei] to the world with an eye to next year’s Tokyo Olympics and Paralympics’ (Sankei Shimbun, 15 February 2019) As critics point out, this approach raises fundamental questions about the government’s interpretation of ethnic harmony, suggesting that the government goal is ‘a superficial inclusion, centred on tourism and void of apologies and guarantees of rights’ (Higashimura 2019). Though the content of the National Ainu Museum is yet to be unveiled to the public, there have been questions about the extent to which it will reflect the history of Ainu people’s long struggles against expropriation and discrimination, and concerns have been raised at the way in which the new Ainu policy as a whole has been framed without any reference to the rights of Sakhalin and Kurile Island Ainu descendants now living in Japan (Tazawa 2017).

The Ainu Association of the Urahoro region of Hokkaido has already responded to the introduction of the law by launching a court case against the national and prefectural governments demanding the right to fish in their traditional salmon catching grounds on the Tokachi River (Tōkyō Shimbun, 13 January 2020). Meanwhile, in January 2020, the depth of the government’s commitment to meaningful ‘harmony’ was further cast into question when Deputy Prime Minister Aso Tarō told a gathering of his constituents in January 2020 that ‘no country but this one [Japan] has lasted 2,000 years with one language, one ethnic group and one dynasty’, thus in one sentence writing the Ainu out of history altogether (Japan Times, 13 January 2020).

Bones of Contention

Ceremony commemorating almost 1000 Ainu people whose remains are held by Hokkaido University, 2013 (Photo: Tessa Morris-Suzuki)

One section of the new Ainu Museum and Park has become the focus of particularly intense dissention. An area on the outskirts of the main museum precinct has been chosen as the site for a ‘Memorial Facility’ (Irei Shisetsu), which will be the last resting place of over one thousand Ainu whose remains were excavated by anthropologists and other researchers without the consent of their communities and taken to museums and universities in Japan and worldwide for research purposes or simply as trophies. The remains of some 1,600 Ainu are still held by research institutions throughout Japan, with more in Britain, Germany, Australia and elsewhere. (It is worth noting that the presence of the Memorial Facility in the Upopoy Ainu Museum and Park complex receives no mention at all in the official publicity brochure on the park that has been prepared for foreign visitors). A number of Ainu groups have been campaigning for years for these remains to be returned to the areas from which they were excavated, and as a result of court cases brought by these groups, the remains of about one hundred people have so far been returned to their communities.

Tomb markers on the graves of Ainu people recently repatriated to Kineusu Village (Photo: Tessa Morris-Suzuki)

The question of the return of remains has become a deeply divisive one within the Ainu community itself. The Ainu Association of Hokkaido (Hokkaidō Ainu Kyōkai) has given its blessing to the government plan. But a number of other individuals and groups – among them the Kotan Association, based in the Yūfutsu district of Hokkaido, and the recently established Shizunai Ainu Association – argue that true ‘repatriation’ must mean the return of remains to the communities from which they were taken, and must involve proper ceremonies conducted by those communities themselves (Shimizu 2018; Shimizu, Kuzuno and Gayman 2018; Nakamura 2019). Although it will still be possible for individuals or groups to seek the return of remains which will be interred in the Memorial Facility, the processes are likely to be complex, and critics argue that the ultra-modernist concrete cube of the Memorial Facility, located as it will be on the fringe of a major tourist attraction, is a wholly inappropriate resting place for the Ainu dead. A number of scholars and activists have suggested that, rather than making the Memorial Facility the main resting place for ‘repatriated’ Ainu remains, the government should be actively seeking out and negotiating with the communities from which the remains came, to ensure that as many as possible can go back to lie in the earth from which they were taken (Nakamura 2019).

The Olympics and Beyond

If one purpose of the Olympics is to display the host nation’s culture and identity to the world, then the 2020 Olympics should most certainly include representations of Ainu culture, both in the opening ceremony and in the events that surround the sports extravaganza. The creation of the Upopoy National Ainu Museum and Park in the lead-up to the Olympics could play a positive role in making international visitors to the Olympics more conscious of Ainu history and contemporary Ainu society. But, given the recent history of Ainu policy in Japan, important questions remain about the relationship between the Olympic celebration of Ainu culture and the underlying issues of indigenous rights.

How will Ainu life be represented in the 2020 Olympics and the cultural events that surround them? Will visitors to the Olympics learn about the ongoing struggles of Ainu communities for recognition of their resource rights and return of their ancestral remains? Will foreign visitors have a chance to hear the voices of Ainu themselves, speaking about the complexity of their life experiences? Will Ainu people themselves determine the way in which their history, culture and aspirations for the future are presented to the world? Or will the ‘Harmony Olympics’ offer a carefully controlled image of Ainu culture as one colourful but unproblematic square in the mosaic of an already-achieved Japanese harmony?

As I have followed media reports of Ainu issues in the lead-up to the 2020 Olympics, I could not help being reminded of the debates that surrounded the presentation of Australian Aboriginal culture in the 2000 Sydney Olympics. In 2000, Aboriginal artistic designs and spiritual traditions formed a key part of the Olympic opening ceremony, and the Australian government was eager to use Aboriginal culture to promote Olympic year tourism, but at the same time, the prime minister of the day, John Howard, was energetically resisting demands for an apology to Aboriginal people for the disastrous effects of state assimilation policies. As a result, the Olympics themselves became the focus of demands for change. Two months before the start of the Sydney Olympics, some 300,000 people participated in a protest march across the Sydney Harbour Bridge, demanding an apology from the government to Australia’s Aboriginal ‘Stolen Generations’ (children forcibly taken from their families as part of state-sponsored assimilationism), and at the Olympic closing ceremony, the rock group Midnight Oil, took to the stage dressed in shirts emblazoned with the word ‘Sorry’, performing the song ‘Beds Are Burning’, with its rousing recognition of Aboriginal land rights: ‘it belongs to them, let’s give it back’. These events became part of the momentum that led to the Australian government’s national apology to the Aboriginal Stolen Generations in February 2008.

The dynamics of Japan’s indigenous rights struggles are different, but nonetheless the controversy surrounding the place of Ainu identity in the 2020 Olympics and their wider cultural setting has the potential to mark a turning point for Japan too. People from throughout Japan and the world who see Ainu culture on display in Olympic ceremonies or who visit the newly opened Upopoy National Ainu Museum and Park will have a chance to ask – how far does the Japanese state truly recognise the rights of Ainu as indigenous people? What hopes do Ainu people hold for the future, and how might these hopes be achieved. In that way, there is an opportunity for the events of this year to go beyond the promotion of cultural tourism and cosmetic kyōsei and open up a serious debate on restoring and promoting the social, cultural, economic and political rights of the Ainu people.

REFERENCES

Center for Ainu and Indigenous Studies, University of Hokkaido. 2010. Living Conditions and Consciousness of Present-Day Ainu. Sapporo: University of Hokkaido.

Higashimura, Takeshi. 2019. ‘No Rights, No Regret: New Ainu Legislation Short on Substance.’ Nippon.com. 26 April. (accessed 3 December 2019).

Japan Times, 14 January 2020, ‘Deputy Prime Minister Taro Aso again courts controversy with remarks about Japan’s ethnic identity.’

Kaneko, Shinsuke and Satō, Yōsuke. 2019. ‘Kantei “Sapporo” Maemuki – Upopoy Shūkyaku mo Kitai’. Hokkaidō Shinbun. 31 October. 3.

Kayano, Shigeru. 1994. Our Land was a Forest: An Ainu Memoir. (Trans and ed. Kyoko and Mark Selden). Westview Press.

Kelly, Tim. 2019. ‘Aiming at Olympic boom, Japan builds ‘Ethnic Harmony’ tribute to indigenous Ainu’. Reuters. 29 October. (accessed 1 November 2019).

Morris-Suzuki, Tessa. 2018. ‘Performing Ethnic Harmony: The Japanese Government’s Plans for a New Ainu Law’. The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus. 16(21) no. 2.

Nakamura, Naohiro. 2019. ‘Redressing Injustice of the Past: The Repatriation of Ainu Human Remains’. Japan Forum. 31(3). 358–377.

Sankei Shinbun, 15 February 2019, アイヌ支援法案を閣議決定 「先住民族」と明記

Shimizu, Yuji. 2018. ‘Towards a Respectful Repatriation of Stolen Ainu Ancestral Remains’. In Gerald Roche, Hiroshi Maruyama and Åsa Virdi Kroik. Indigenous Efflorescence: Beyond Revitalisation in Sapmi and Ainu Moshir. Canberra: Australian National University Press. 115–120.

Shimizu, Yūji, Kuzuno Tsuguo and Gayman, Jeffry. 2018. ‘Ainu Experience’. Presentations given at the International Symposium ‘Long Journey Home: Repatriation Symposium’. National Museum of Australia, Canberra, 7 May 2018.

Shimizu, Yūji, Hatakeyama, Satoshi, Maruyama, Hiroshi and Ichikawa, Morihiro. 2019. ‘Recognition at Last for Japan’s Ainu Community’. Presentation to the Foreign Coreespondents’ Club of Japan. 1 March.

Siddle, Richard. 1996. Race, Resistance and the Ainu of Japan. Abingdon: Routledge.

Tamaki, Taku, 2019. ‘The Olympics and Japanese National Identity: Multilayered Otherness in Tokyo 2016 and 2020’. Contemporary Japan. 31(2). 197–214.

Tazawa, Mamoru. 1997. ‘Karafuto Ainu kara Mita Ainu Seisaku no Kihon Mondai’. Presentation to the 5th forum of the Citizens’ Alliance for the Examination of Ainu Policy, 18 June (accessible on the Alliance website).