Abstract: Yun Isang (1917-95) was one of Korea’s most prominent composers in the twentieth century. From 1957, the year he moved to West Germany, to his death in 1995, he had an internationally illustrious career, garnering critical acclaim in Europe, Japan, the United States, and North Korea. In South Korea, however, he became a controversial figure after he was embroiled in a national security scandal in 1967. As part of this incident, dubbed the East Berlin Affair at the time, Yun Isang was abducted in West Germany by the Korean Central Intelligence Agency and charged with espionage for North Korea. This experience of victimization, which also included torture, imprisonment, and an initial death sentence, turned him into a vocal critic of Park Chung Hee and an overseas unification activist in contact with North Korea. This article remembers the moral and political framings of Yun Isang in South Korea against a recurring politics of forgetting that masks the magnitude of violence that was wielded in the name of national security. It traces coverage of Yun in several mainstream newspapers from the first mention of his name in 1952 to 1995. It argues that representations of Yun were mediated by a tension between national artistic progress and national security, one of the central tensions that defined South Korea’s Cold-War cultural politics.

Keywords: Yun Isang, Cold War, South Korea, West Germany, North Korea, East Berlin Affair, European avant-garde

Yun Isang (1917-95) was one of a small number of composers from South Korea who had a prominent career in postwar Western Europe. Born near the southern city of Tongyeong (T’ongyŏng) in Japan-colonized Korea, Yun studied composition and cello at the Osaka School of Music in 1935. In post-liberation Korea, he was a promising composer in Seoul. In 1956, he left for Paris to study composition and settled in West Berlin in the following year. From 1960, as his works were selected for prestigious music festivals, Yun found himself an emerging figure in the European avant-garde. He garnered praise especially for compositions that were influenced by traditional Korean music. From the early 1970s until his death in 1995, his music was performed in big and small concerts in Germany, Japan, the United States, France, North Korea, and beyond. Reflecting his international esteem, Yun also attracted diverse students, including Toshio Hosokawa from Japan, Jolyon Brettingham Smith from Great Britain, and Conrado del Rosario from the Philippines. But there was one country where his name was under constant threat of erasure: South Korea.

Yun Isang’s strained relations with his native country began during the Park Chung Hee regime (1961-79). In summer of 1967, Yun was abducted by members of South Korea’s Korean Central Information Agency (KCIA) in West Berlin and forced onto a Seoul-bound flight. He was one of the 34 South Koreans who were arrested in Western Europe as part of the East Berlin Affair, a counter-espionage round-up that the KCIA staged with little evidence. Yun, who had visited North Korea from Europe in 1963, was charged with espionage for North Korea. He was tortured, tried, and given a death sentence.1 Meanwhile, his abduction had caused West German, Japanese, and American colleagues to form action committees in Bonn, Washington D.C., and Tokyo, in order to raise awareness of the human rights abuse involved in Yun’s extradition and indictment. One particularly powerful campaign came from Wilhelm Maler, the president of the Freie Akademie der Künste in Hamburg at the time. He drafted an appeal for Yun’s release that was signed by such luminaries as Igor Stravinsky, Karlheinz Stockhausen, György Ligeti, Herbert von Karajan, and Mauricio Raúl Kagel. Due to this and many other international campaigns, Yun was released from prison and was allowed to return to West Germany in the spring of 1969.

From this point on, Yun Isang was an inconvenient figure for the Park regime. As a reminder of state violence, he also became an icon of opposition within South Korean cultures of resistance, but any public discourse about Yun had to be shaped carefully and strategically as it was under the state’s surveilling eyes. As former dissidents have attested, in the 1970s, even mentioning Yun’s name was considered a subversive act.2 Yun became an even more delicate subject after 1973 as he transformed himself into a vocal overseas critic of Park and a unification activist in contact with North Korea. He would never again set foot in South Korea.

The victimization of Yun under the Park Chung Hee regime is no longer a sensitive subject in South Korea, where a number of famed former dissidents have entered congressional politics and the presidency since 1998. However, almost three decades of state-centered narratives and media’s self-censorship surrounding Yun have left a legacy of taboo, and to date, there are no comprehensive studies that document the ways in which Yun Isang was represented and discussed in the South Korean media during his career. Scholarship on Yun in English and Korean has tended to focus on stylistic analysis of his compositions, celebrating the ways in which Yun tested the boundaries of Western art music, rather than addressing the ways in which he contested the boundaries of political and moral legitimacy.3 While these largely musicological studies make a significant contribution to scholarship usually dominated by preoccupation with Euro-American composers, they have left under-explored Yun’s contested relationship with South Korea – as a victim of the brutality of the Park regime, as a democratization and unification activist in contact with North Korea, and as a celebrated composer.

This article remembers the political and moral framings of Yun in Cold-War South Korea against a recurring politics of forgetting that masks the magnitude of violence that was wielded in the name of national security. I examine accounts about Yun in South Korean newspapers from the first mention of his name in 1952 to his death in 1995, drawing on more than seventy articles in three papers that were vulnerable to state pressure – Tonga Ilbo, Kyŏnghyang Sinmun, and Maeil Kyŏngje (after 1988, I also bring in a number of articles from the dissident newspaper Hankyoreh). To search for Yun Isang in mainstream newspapers in the second half of the twentieth century – particularly during the Park and Chun regimes and to some extent during the Kim Young Sam administration – is to be overwhelmed by the collaborative relationship between the media and the state. Of course, the media was not an official mouthpiece of the state, and individual journalists at various times sought to negotiate the terms of what could and could not be said about Yun and other dissidents. But reports on known dissident figures tended to conform to official Cold-War narratives, attesting to a print culture where writers of any stripe, including those with activist leanings, had to use the frames of hegemonic discourse if Yun’s name was to be printed in public documents.

The state’s influence on the press, however, did not mean that the newspapers published a uniform image of Yun across the decades. Yun proved to be a challenging figure to represent as he confounded the two-part commitment of the state to “the display of ‘South Korea’… as a developmentalist space at once opposing and mirroring its northern counterpart in the global Cold War.”4 As I argue, a tension between notions of artistic progress and national security pervaded newspaper reports on Yun. On one side, Yun’s success in Western Europe strongly resonated with the developmentalist discourse that had shaped even the sphere of art and music in post-colonial, Cold-War South Korea. Yun’s success made him an exemplar of South Korea’s ascendance within artistic cultures of the Cold War’s Western bloc. On the other side, Yun’s contacts with North Korea and his activism around national unification could not be assimilated into state’s national security ideology, which required an excision of North Korea and any elements associated with it. I highlight the tension between the desire to claim exemplars of national progress and the problem of regulating their political criticisms as a persistent feature of Cold War cultural politics in South Korea, as elsewhere.

In what follows, I organize the receptions of Yun Isang into seven periods, based on perceptible shifts in the tone and message of news coverage. The first two sections examine news articles published prior to the East Berlin Affair, exploring the lesser-known stories of Yun’s breakthroughs in South Korea and West Germany. The subsequent sections consider how the press represented Yun during and after the Incident and how these representations swayed in response to changes in the domestic political climate and Yun’s international activities.

1952-55: Recognition in South Korea

The East Berlin Affair of 1967 promoted Yun’s image as an overseas South Korean dissident in the Western imagination, but references to his name in South Korean newspapers before his departure to Germany contest this association. These early references from the early-to-mid 1950s demonstrate that Yun moved in mainstream cultural organizations structured by South Korea’s anti-communist, pro-U.S. stance in the wake of the Korean War. One of the early new articles (if not the earliest) to mention Yun is from March 1952, in the midst of the Korean War. It advertised a concert of operettas and film music organized by the Wartime Composers’ Association (chŏnsijakkokka hyŏphoe) at a café.5 Yun was one of the two composers whose music was featured. Other mentions from the early 1950s link Yun to a number of establishment organizations, such as the Korean Composers Association (han’guk chakkokka hyŏphoe) and the Music Fan Club (myujik p’en k’ŭllŏp).6

At this time, what distinguished Yun from many of his contemporary composers in South Korea was not his politics but his attempt to write art music at the juncture of modernism and nativism. Chŏn Pongch’o, a music professor at Seoul National University, was one of the first critics to write about Yun’s attempt to synthesize Western musical modernism and Korean aesthetics. In his rave review of the composer’s piano trio and string quartet for Tonga Ilbo in 1955, Chŏn wrote:

In these two works, I feel the undercurrents of our ancestors’ sorrow and happiness, love for one’s hometown, and the smell of the earth. In the music dwells a kind of national religion from the three southern provinces, which Yun Isang possesses in his body. They are musical paintings…in which a sense of Eastern mystery and a people’s tradition compete seriously with a modern consciousness.7

Chŏn’s review is significant as one of the first pieces of music criticism to note Yun’s intercultural style. As such, it prefigured later Western and Japanese critics’ evaluation of Yun’s works.

In his Tonga Ilbo review, Chŏn added that Yun was a more advanced composer than his Korean peers, describing the reviewed pieces as “a revolution…produced in a country where people who harmonize children’s songs call themselves composers.” Such an evaluation, while divulging Chon’s condescending attitude toward South Korean composers in the mid-1950s, nevertheless sheds light on the historical circumstances under which Western music entered Korea in the early twentieth century. Western music was introduced as part of Japanese colonial education and U.S. religious missionary activity, rather than as concert-hall repertoire. Due to these historical beginnings, Korean composers of this music who came of age during the colonial period (1910-45) tended to write for educational or Christian initiatives, rather than for the concert hall. It is interesting to note how Yun’s trajectory both conformed to and contested the career patterns of his generation. Like many of his contemporaries, he studied Western music first with U.S. missionaries in Korea and then studied composition in Japan in the late 1930s, beginning at the Osaka School of Music and later with Ikenouchi Tomojirō.8 However, unlike many of his contemporaries, Yun aspired to write art music in the vein of Western modernism.

In 1956, the 39-year-old Yun went to Paris to further his composition studies, thanks to a Seoul City Cultural Award he received. Kyŏnghyang Sinmun and Tonga Ilbo advertised a farewell gathering organized by the Korean Composers Association and Music Fan Club, treating his forthcoming voyage as an affair of national importance.9

1956-66: Overseas Success at a Time of Domestic Transition

After a year at the Paris Conservatory, Yun moved to West Germany in 1957 and studied with Boris Blacher at the Berlin University of the Arts. Thereafter, Yun’s reputation grew in the contemporary art music scene in West Germany. A turning point was attending the Darmstadt International Summer Course for New Music in 1958. This annual event had become a key locus of support and network for male avant-garde and experimental composers from the United States and Western Europe by the mid-1950s. Composers from Latin America and Asia made up a minority. Darmstadt gave Yun the opportunity to get to know established and new composers and to become familiar with the latest trends. Among the composers he interacted with at Darmstadt in 1958 was John Cage (1912-92), who was perhaps the most influential figure in the trans-Atlantic avant-garde at this time, and Paik Nam June (1932-2006), a Korea-born artist who had lived in Hong Kong and Japan before moving to West Germany in 1956.10 Yun’s experiences at this center of new music helped him join a small number of East Asian composers who would become participants of the Euro-American avant-garde in the 1960s and 70s. Such composers included Yun, Paik, the Japanese composer Ichiyanagi Toshi, and the Chinese American composer Chou Wen-Chung.11

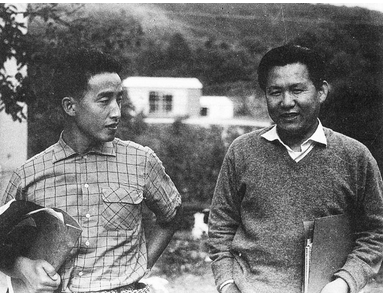

Figure 1: Paik Nam June (left) and Yun Isang in Darmstadt, 1958.

Figure 2: from left, Paik Nam June, Yun Isang, Nomura Yoshio, and John Cage. Darmstadt, 1958.

After 1958, Yun’s works were selected to premiere at prestigious festivals – Music for Seven Instruments in Darmstadt (1959), Five Pieces for Piano in Bilthoven (1959), and String Quartet No. 3 in Cologne (1960). In 1962, the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra premiered Bara, a piece that alluded to a Korean Buddhist ceremony. Each of these successes delayed his plan to return to Seoul. A Ford Foundation grant in 1964 enabled him to bring his family from South Korea, making his move to West Germany permanent.

Two South Korean news articles involving Yun Isang in the wake of his first European breakthroughs were written by Yun himself. In 1960, Yun wrote to Kyŏnghyang Sinmun twice from West Germany, and both correspondences demonstrate that he saw himself not only as a part of his adopted world in West Germany but also as an extension of South Korea’s art and music scene. The first of these, a letter addressed to the public, appeared in the newspaper’s May 21 issue.12 Yun briefly described Music for Seven Instruments and reported that it was performed or broadcast in West Germany, Italy, Belgium, Sweden, France, Japan, and Denmark. This letter also signaled that Yun was closely following South Korean politics from West Germany: the opening pays homage to “the many students who shed blood for their country,” referring to large-scale street protests of April 1960, which had ousted the then-president Syngman Rhee following a fraudulent election. Yun’s second correspondence passed on the news of a forthcoming Japanese art exhibition in a West German gallery. Kyŏnghyang Sinmun, paraphrasing Yun’s letter, reported that this gallery was hoping to include “the works of six contemporary painters in the Korean art scene, who can rank with or surpass post-impressionist painters who represent Japan’s younger generation.”13 That Yun took it as his duty to pass on this news to South Korean readers suggests that he was eager to increase Korean representation relative to Japanese representation in West Germany’s art scene.

After 1960, there is no record of Yun’s direct correspondence with South Korean newspapers. One factor, other than his busy schedule at the time, is his disappointment with political developments in South Korea. According to Der Verwundete Drache (The Wounded Dragon), a book-length interview with Yun by the writer Luise Rinser published in 1977, Yun was shocked by the news of Park Chung Hee’s rise to power through military coup (the full Korean translation of this interview was not published until 1988).14 Park’s “military revolution” fundamentally changed South Korean society: it elevated the military as the most authoritative ruling body and empowered a regime that justified its brutality by citing the need to eliminate communist and pro-North Korean elements in South Korean society. It became increasingly difficult for the press to maintain autonomy as the Park regime sought to punish or co-opt dissenting journalism through intimidation, financial retaliation and the National Security Act. It is instructive that within six months of the coup, Park’s Revolutionary Court executed Cho Yongsu, the owner of a center-left newspaper that had been opposed to the conservatives’ hardline policy against North Korea over the objection of the International Press Institute.15

Yun no longer maintained an active relationship with the mainstream South Korean press after 1960, but favorable mentions of Yun increased, reflecting the cosmopolitan aspirations of South Korea’s cultural scene. Articles from 1961 to 1962 show that South Korea’s regional and national institutions conferred awards on Yun.16 In 1964, Tonga Ilbo took note of profiles of Yun in West German newspapers The Telegraph and Der Tagesspiegel’s.17 In 1965, a contemporary music festival organized in Seoul cited Yun as inspiration for the event.18 Yun’s premieres in Hanover and Berlin in 1965 and 1966 were touted as “overseas accomplishments,” and the premiere of Reak at the 1966 Donaueschingen Festival was summarized as “our music making a mark in West Germany.”19 In February 1967, only five months before Yun’s forced return to Seoul, Hwang Byungki, then an emerging figure in Korean traditional music, praised Reak, describing it as a “fine work that reconstituted the traditional aesthetics of Korean music through modern music techniques”20 (see below). Clearly, Yun’s recognition in Europe strongly resonated with the rising desire of South Korean society for recognition in the Cold War’s western bloc, especially given the dearth of overseas figures who were seen to represent South Korea.

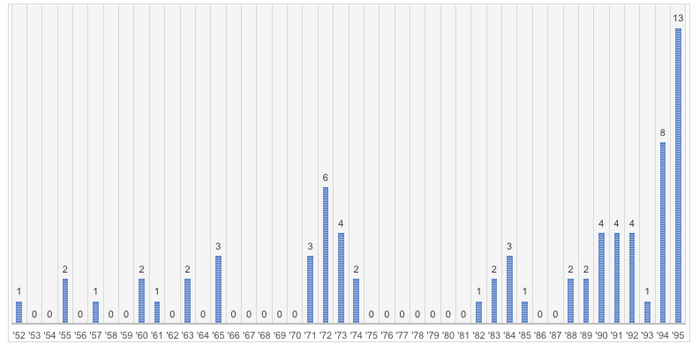

The overwhelmingly positive reception of Yun was felt in Seoul’s art music scene as well. Yun’s pieces were included in concerts more frequently than before (see Figure 3). Almost all of the performed pieces were short art songs, which were much easier to learn, stage, and appreciate, rather than challenging instrumental compositions like Reak, which Yun came to be known for in West Germany. This leaning toward art songs reflected not only the musical taste of the concert-going public, but also the dearth of performance infrastructure for contemporary Western art music in early 1960s Seoul. For example, there was no professional orchestra dedicated solely to experimental music. However, at least one news article from 1960 tells us that a music café played a recording of Yun’s instrumental pieces – Music for Seven Instruments in Darmstadt (1959), Five Pieces for Piano in Bilthoven (1959), and String Quartet No. 3 (1960).21 This café, the now-legendary Renaissance music room (Runessangsŭ ŭmaksil), was a mecca for college-educated aficionados of European classical music.

Figure 3: number of concerts during which Yun’s work(s) was performed in South Korea, annually from 1952 to 1995. Compiled by the author based on reports of concerts in Tonga Ilbo, Kyŏnghyang Sinmun, Maeil Kyŏngje, and Hankyoreh.

1967-68: Defamed and Romanticized during the East Berlin Affair

In the summer of 1967, Yun’s positive image was abruptly overturned, and performances of his music halted in South Korea (see Figure 3). On June 17, Yun was kidnapped in West Germany and forced onto a Seoul-bound flight by the Korean Central Intelligence Agency (KCIA), Park Chung Hee’s main instrument for political control. Yun’s extradition was part of a roundup that arrested approximately 34 South Koreans in Western Europe on charges of espionage for North Korea. Among the arrested were Lee Ung-no, a celebrated painter in Paris; Pak Nosu, an international law researcher at Cambridge; and Ch’ŏn Pyŏnghŭi, a German literature student at Heidelberg University. Later accounts and testimonies reveal that these arrests and the ensuing torture were based on the KCIA’s inflated and alarmist reading of a philosophy scholar’s “confession” about the possible vulnerability of South Koreans in Europe to the reach of the North Korean state.22 These accounts also tell us that Park Chung Hee had much to gain by raising the threat of North Korea in the summer of 1967 as he sought to stifle growing protests against his efforts to abolish term limits for the presidency by controlling the national assembly. In this context, the KCIA staged a national security crisis to hamper the protests and to steer public opinion in Park’s favor, a tactic that the Park regime used multiple times in the face of popular dissent.23

The arrest of overseas Koreans became the headline for major newspapers on July 8 (see Figure 4). These initial reports, replete with direct quotations from the KCIA’s statements, were little more than a retelling of the state’s official narrative. Consider, for example, the report in Kyŏnghyang Sinmun:

This operation team is the largest organization of spies engaged in international espionage in the West and domestically, and it is notable for including university professors, doctors, artists, government workers, and renowned figures, as well as young intellectuals. According to the announcement, most of them were lured into the recruitment operations of the North Korean puppet regime [pukkoe], which is based in East Berlin, while they were studying in Western Europe. They were then lured to Pyongyang via the People’s Republic of China and the Soviet Union, admitted into the Communist Party, and given funds to further their studies or obtain doctoral degrees. After their studies, some of them came back to South Korea with the mission to infiltrate politics, academia, press, administration, or legislation.24

The uncritical subscription to the KCIA’s position in this and other newspapers in the wake of the roundup exemplified the media’s docility under Park.25 This was especially true of Kyŏnghyang Sinmun. While today it leans toward progressive and centrist reporting, in 1964, it was auctioned off to an automobile corporation by the government after the paper’s owner challenged Park’s media censorship.26

Figure 4: “Arrest of North Korea’s East Berlin communist espionage operation,”

Kyŏnghyang Sinmun, July 8, 1967. Yun Isang’s photograph is top left among the ten photographed figures.

Newspaper coverage surrounding the trials turned Yun into a poster boy of what was called “North Korea’s East Berlin Communist Espionage Operation against the South” (tongbaengnim kŏjŏm pukkoedaenam kongjaktan sagŏn). This term, coined by the KCIA, marked East Berlin as the center of North Korea’s recruitment of overseas South Koreans in Europe for the purpose of deposing the South Korean state. Reports of the trials record the KCIA’s determination to inflate a trip taken by Yun to Pyongyang in 1963 from Europe, in order to establish him as a spy.27 In response, Yun maintained that his visit was motivated by his wish to search for a friend who had gone to North Korea and to see an ancient mural, which he wished to use as a source of inspiration for a composition. He also clarified that the money he received from North Korean officials were personal gifts, not operation funds for espionage, as the KCIA had alleged. The questions directed at Yun and retold in newspapers reflected the state’s determination to criminalize a range of diasporic South Korean activities that rested on the permeability of Cold-War borders in Europe – for example, socializing with North Koreans at a North Korean restaurant in East Berlin.

More sympathetic reports also began to appear in early December of 1967, a few weeks before the first trial. Such reports were a response to the increasing international attention that the case of Yun and the broader scandal were attracting.28 Nevertheless, an awareness of increased international attention among domestic journalists did not mean they could freely introduce foreign coverage surrounding Yun and the East Berlin Affair. At this time, journalists could pay dearly if their reports on world affairs did not conform to the state’s position on North Korea. For example, in 1964, the KCIA jailed the well-known reporter Rhee Yŏnghi for reporting the United Nations’ consideration of granting admission to both North Korea and South Korea – an objective of both states at the time.29 Given such restrictions, coverage of Yun had to be carefully framed within the limits of acceptable discourse. News reports tended to appeal to Park’s generosity and underscore Yun’s achievement as a composer, leaving aside criticisms of the Park regime in foreign media30. One of the first articles in this vein reported that the South Korean government approved Bonn Opera House’s request for Yun to finish writing the opera Die Witwe des Schmetterlings (known as The Butterfly Widow), which was commissioned prior to his kidnapping to Seoul. This article portrayed the Park administration as a magnanimous body that accommodated a foreign cultural organization and the artist and presented Yun as a genuine artist who was devoted to his calling even in jail.31 Another trope connected Yun’s fate in the trial to the issue of South Korea’s prestige in the international arts community. An article in Kyŏnghyang Sinmun suggests that Yun’s lawyer pushed this angle. A quote from the lawyer states: “many foreigners including the international composer Stravinsky are petitioning for a generous verdict, and it is hoped that he can continue to compose as a free person so that he can continue to enhance the nation’s prestige.”32

The number of reports citing international attention increased after Yun received a death sentence on December 13, 1967. This increase reflected more robust campaigns for Yun abroad as well as pressures from the West German and French governments. South Korean reports of such campaigns never exceeded the limits of domestically accepted discourse, but they did convey to the public that an unprecedented scale of international attention was being paid to a jailed South Korean artist. For example, a Kyŏnghyang Sinmun feature on the second trial (March 1968) drew attention to two West Germans who attended the trial as witnesses and reported that they vouched for Yun’s patriotism towards South Korea, commitment to anti-communism, and low opinion of communist music.33 Several articles in the summer of 1968 pointed to Yun’s international standing by announcing that he was granted membership in West Germany’s Hamburg Arts Academy and commissions from the West German Radio and Mills College in the United States.34 An article from November 1968 covered a recent performance of Yun’s Reak at Carnegie Hall in New York City alongside works by stellar figures of the international avant-garde, such as Charles Ives, Krzysztof Penderecki, and Milton Babbitt. The meaning of this report was clear: it advertised the performance of Yun’s signature Koreanist work at the heart of the Cold-War free world. This article also included a translation of the conductor Lukas Foss’s petition to President Park, which he had read aloud before the performance of Reak:

‘I do not know what crime Yun Isang committed and I don’t know the details, but I know that his works are beautiful and magnificent, and that they exclude any political intention,’ he stated. ‘Even if his crime were onerous, we hope that paths are open so that he can contribute to the Republic of Korea through superb composition as a free person.’35

All in all, news coverage of Yun Isang in the course of 1968 fashioned a number of narratives that would prove influential in subsequent decades. They framed the artist’s brilliance, his international reputation, and the apolitical nature of his works as indications of his integrity. These reports most likely put at least some pressure on Park, but they also meant that the issues of legal justification and political terror surrounding the East Berlin Affair could not be raised directly.

1969-74: A Korean Representative in the European Avant-Garde

Yun was released in February 1969 and returned to Berlin in March in the face of increased international criticism as well as reports by a number of South Korean journalists who covered the case extensively. In August 1970, newspapers reported that Park granted a special presidential pardon to Yun and almost all of the other public figures arrested in 1967.36 This recourse to presidential pardon, at odds with the severe penalties previously given to the indicted individuals, suggests that the Park regime wanted to extricate itself from a scandal that was attracting mounting international attention while still framing Yun and others as criminals who were forgiven by the state.37

With the pardon as a starting point, Yun became the subject of dozens of articles in the South Korean press each year until 1975. None of them mentioned the East Berlin Affair or Yun’s victimhood. Instead, they focused on the recognition of Yun’s music in Western contemporary music circles. Usually written by guest contributors or journalists for culture sections, such articles imagined Yun as a kind of South Korean representative at the international center of contemporary art music. For example, Kim Chung-gil’s review of the Donaueschingen Festival in West Germany for Tonga Ilbo illustrates how young South Korean composers like Kim understood Yun as a Korean representative in a music scene too “advanced” for Asian composers:

Because Yun Isang of Korea premiered Reak in the 1966 festival and received critical acclaim, participants were interested in South Korean composers of contemporary music. To give a general review of the festival in my own way, the pursuit for the creation of new sounds, new forms, and new performance techniques almost made me dizzy. In short, there will be many problems for Eastern composers to exceed these composers.38

Other than aspiring composers like Kim Chung-gil, established figures in South Korea’s traditional music praised Yun for using Korea’s cultural asset as a source material for Western art music. For example, Han Manyŏng, in an op-ed for Tonga Ilbo, described Yun’s music as “a rational explanation of Korean court music” and considered it a rare example of successful hybrid work in a crowded scene of “touristic” fusion music.39

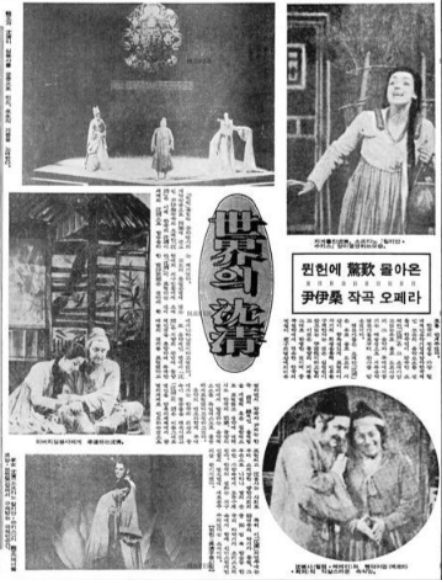

Favorable appraisals of Yun’s music peaked in 1972, when he was commissioned to write an opera for the opening ceremony of the 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich. Newspapers proudly reported that Yun’s chosen subject for the opera was Simch’ŏng (spelled Sim Tjong by Yun), a Korean folktale about a filial daughter and her blind father. News articles presented the opera Sim Tjong as a hybrid work showcasing “Taoist, Buddhist, or Confucian ideology,”40 guided by the composer’s own wording of the program.41 Overall, reports of Sim Tjong were wrapped in nationalistic fervor. They treated the performance of the opera as a sign of Korea’s ascendance in the world (see Figure 5). Im Wŏnsik, a South Korean conductor who attended the opera in Munich, voiced this sentiment in an interview with Kyŏnghyang Sinmun: “when was the last time that Korea had inspired Western society this much, in opera or otherwise, in our country’s long history?”42

Figure 5: “Simch’ŏng in the World,” Kyŏnghyang Sinmun, August 9, 1972.

From 1971 to 1974, Yun’s music appeared in at least eleven concerts in South Korea, suggesting that the state did not raise objection to public performances of his music (see Figure 3). Particularly notable were two new music festivals held in 1971. The first of these, a festival organized by the conservative Music Association of Korea, performed Yun’s Loyang, which used a type of Korean court music that drew on Tang-dynasty Chinese music as source material.43 The second of these programmed not only Yun’s music but also that of his South Korean students who had recently returned from Hanover, Paik Byung-dong and Kang Sukhi.44 Park and Kang subsequently became leading figures in South Korea’s experimental music scene. In this way, Yun shaped the course of new music in his native country from his diasporic space in West Germany.

That Yun’s music could be praised and performed in South Korea from 1971 to 1974 despite his prior charge and despite even stronger censorship in the early 1970s speaks to the pervasive nationalistic desire for “free-world” cosmopolitanism at public and official levels. Yun, as a rare case of a successful Korean artist in the Cold War’s western bloc, was a compelling story, and as long as references to inconvenient truths were muted, he could be accommodated in the media. It should be remembered that it is partly this widespread desire for cosmopolitanism that made it possible for dissenting intellectuals and journalists in South Korea to keep mentioning Yun’s name – an implicit reminder of state violence – in print media. However, opportunities for even this type of oblique resistance largely disappeared when Yun spoke out against Park at an international press conference.

1975-81: Blacklisted

In 1975, there was a sudden drop in references to Yun in South Korean newspapers. There were also no reported performances of his music from 1975 until 1982, suggesting that his works did not pass the censorship board (see Figure 3). This silence stood in stark contrast to Yun’s productivity during this period. From the perspective of Yun’s trajectory as a composer, the second half of the 1970s was a time when he explored large-scale concertos and orchestral suites. These works, which prepared him for a cycle of symphonies in the 1980s, were noted for expressing greater depths.45 Among his most acclaimed pieces from this period was his Cello Concerto, which was premiered at the International Festival in Royan, France in 1976 (see below). Critics discerned Yun’s experience of suffering in this piece, and Yun affirmed that the abstract condition of oppression portrayed in this piece was rooted in his personal experience of incarceration. He also added that the cello, his favorite instrument, conveyed his voice and spirit.46 In addition to this and other concertos, Yun continued to develop his signature Asianist style in Muak (1978) and Fanfare and Memorial (1979). Beyond breakthroughs in composition, a new teaching position at the Hochschule der Künste in Berlin gave him the opportunity to influence a growing number of students. His students in the late 1970s included Hosokawa Toshio, a Japanese composer who had admired Yun since hearing a performance of Reak and Dimensionen in Tokyo in 1971.47

Youtube video of Cello Concerto

The imposition of silence in South Korea was a response to Yun’s leadership role in the overseas South Korean democratization movement. According to historian Gavan McCormack, this movement, “stirred first by government abductions and the state terror tactics of the 1960s,” came to have the characteristics of an international movement in the 1970s, with networks of overseas Korean and foreign activists established in Tokyo, Berlin, and London, among others.48 Activists of this movement spoke against the mounting violence under Park and sought to create links between North and South Korea, against the model of competition and confrontation that gave cover to the Park regime’s human rights violation. Yun worked with two groups that played a pivotal role in this movement: Hanmintong49 (Korean Democratic Unification Alliance in Japan), a Zainichi organization, and Hanminryon50 (Korean Overseas Alliance for Democratic People’s Unification), an umbrella group comprising dissidents in Europe and North America.51 Yun’s press conference in Tokyo in 1974 symbolized coalition building between these two groups and presented him as a leader of this coalition. At this event, he spoke about his experience of torture by the KCIA and demanded the release of Kim Dae Jung, then an opposition politician who was abducted from Tokyo by the KCIA in 1973.52

In 1977, South Korean newspapers broke their silence on Yun. They brought him up in the context of a rally in Tokyo that brought together Yun and other activists from different countries. Reports of this rally called them “anti-Korean (banhan) figures” and supported the state’s position that the Japanese government should not have allowed such a rally to take place in the first place.53 An anonymous editorial that appeared in Kyŏnghyang Sinmun is notable for the extent to which it sounds like government propaganda:

It is a real pity there was an anti-Korean rally of approximately one hundred overseas anti-Korean figures in Tokyo around Independence Day… It is a widely known fact that Hanmintong is a Viet Cong organization that engages in espionage at the command of North Korean puppet regime… Most of its frontline leaders were people who fled or were expelled for committing corruption and all kinds of wicked deeds while they served in public office in the Republic of Korea… Yun Isang is someone who actually received prison sentence during the East Berlin Affair for visiting Pyongyang, and the former U.N. officer Im Ch’angyŏng had also committed considerable offence. It is truly absurd that they go around deceiving good overseas Koreans as they present themselves as democratic figures or nationalist fighters.54

The pro-establishment nature of this editorial exemplifies the self-censoring media environment in the last years of the 1970s. At this time, Park Chung Hee’s Yushin Constitution (1972-79), which gave sweeping executive power to the president and suspended constitutional freedoms, posed additional barriers to autonomous journalism.

The blacklisting of Yun Isang in the media was also reproduced in South Korea’s Western art music scene. This took the form of an exposé of Im Wŏnsik’s guest-conducting of Yun Isang’s Muak with the Berlin Symphony Orchestra in Germany, in a 1979 issue of Wŏlgan ŭmak (music monthly). Im, a prominent figure in South Korea’s orchestras and elite music education, was a longtime colleague of Yun who had testified on behalf of Yun’s innocence during the East Berlin Affair. He had also attended Simch’ŏng in Munich in 1972. The exposé, titled “Shocking News: The Performance of Yun Isang’s Music Ignites a Debate about Anti-communism within the Music Scene,” reprinted the concert program and published commentaries by nine classical music professionals in South Korea. The majority of the commentators disapproved of Im for collaborating with Yun abroad. A music critic stated: “Yun Isang has committed considerable offense to Korea. We have avoided performing his music, and we have been cautious in establishing relations with him. Therefore, Im, who already knows this well, should not have gone to Germany.”55 A composition professor argued that anticommunist nationalism should be a priority over questions of artistic value: “Before evaluating Yun’s works as art, [it should be noted that] it is improper to take interest in it or to like it. This is common sense known to every South Korean citizen, so to sympathize with a communist even outside Korea is to deviate from Koreans’ position.”56 A composer branded Yun as a threat to freedom: “It is possible to create music freely and perform freely because this country is a free country. Anyone who harms this free country is the enemy of this freedom and our enemy.”57 Overall, this published forum displayed the extent to which key players in South Korea’s art music community had assimilated the tenets of establishment discourse in the late 1970s.

1982-87: Chun Doo Hwan’s Bid for Yun

The Manichean dynamics that had characterized the reception of Yun in the 1970s were repeated during Chun Doo Hwan’s presidency (1980-87), Park Chung Hee’s successor regime that also began with a military coup. Under Chun, the press’s political conformity was arguably even stronger. This is because Chun imposed thorough pre-publication censorship of newspapers during the martial law period (1980) as he sought to normalize his power in the face of enormous opposition. During this uncertain time, censors backed by the Defense Security Command were dispatched to newspaper headquarters to mute reports of opposition and other inconvenient news, particularly the brutal killing of demonstrating citizens in Kwangju in 1980.58 This iron-fisted beginning galvanized opposition (which would eventually cause Chun’s downfall), but it also led to an early co-optation of key media executives.

After Chun formally became the president through a rigged election in August 1980, his media strategy became one of diversion. Sometimes called “cultural policy” (munhwa chŏngch’aek), this tactic presented Chun as a generous steward of cultural liberalization. It promoted cultural hallmarks of middle-class lifestyle to divert public attention away from politics, especially the regime’s illegitimate beginning and its brutal response to the Kwangju demonstration. Indeed, as media historians such as Kang Chunman have pointed out, it was during Chun’s rule that the state-enforced curfew was lifted, professional baseball was inaugurated, entertainment shows were broadcast in color TV, and massive popular music festivals were offered to the public.59 Classical music was only a minor component of the cultural policy, but like other spheres of cultural life, it was reshaped to fit the framework of leisure consumerism in the early 1980s. The founding of magazines such as Kaeksŏk (the Auditorium) and Ŭmaktonga (Music East Asia), as well as an increase in classical music education, concerts, and recordings expanded the audience for a music that had previously been tethered to an elite base.

A number of reporters under the Chun administration appealed to the cultural policy when they suddenly brought up Yun Isang’s name in 1982. In August 1982, they introduced an upcoming two-day concert dedicated to Yun in a celebratory tone, seemingly forgetful of the condemnations four years prior. Their reports showed every indication of the regime’s sponsorship as well as collaboration between the media and the government: they promised the South Korean premieres of Yun’s orchestral and chamber works at two state-sponsored theatres and praised the government’s intention of “allowing the performance of works of artistic value regardless of the artist.”60 Coverage leading up to the concert drew attention to the event’s international and liberal characteristics, in line with the official cultural policy as well as the cultural refinement discourse that had marked class aspirations in 1980s South Korea. It advertised that “classical music aficionados” will have the chance to purchase scores of over sixty pieces by Yun and publicized a roster of European musicians who were coming to Seoul to perform during the event.61 The performance scene in Seoul also accommodated this sudden shift: performers could play Yun’s pieces in public concerts (see Figure 3), and even the Tonga Music Concours, an elite competition for aspiring student performers, included Yun’s art song Talmuri in its contest repertoire.62

Upon closer reading, it becomes clear that the sudden embrace of Yun in 1982 was motivated by the regime’s desire to coopt him for the 1988 Seoul Olympic Games. Cultural policy par excellence, the Olympics became a buzzword in South Korean media following the successful bid in 1981. In the early 1980s, the government, in collaboration with media elites, began to set the agenda to meet international standards during the Olympics, and it was in this context that the authorities organized “Yun Isang Night” and made subtle bids for Yun’s participation. In a 1982 issue of Maeil Kyŏngje, we can find a suggestive appeal by Cho Sanghyŏn, then the president of the Music Association of Korea and a member of the Olympic preparation committee. Previously, he had branded Yun a communist in the 1979 exposé in Wŏlgan ŭmak. Cho highlighted the importance of “leaving a positive image of Korea” during the Olympic Games and ended his piece with the following: “We remember that Yun Isang’s piece Simch’ŏng was premiered during the opening ceremony of the Munich Olympics.”63 Around the same time, a journalist at Tonga Ilbo also recommended opening the Olympics preparation committee to Yun Isang and “other artists of international stature who cannot engage in domestic activities for various reasons.”64 Yun himself confirmed in a later interview (1993) that the Chun administration made a private request for his participation in the Seoul Olympics.65

In the end, Chun’s bid for Yun foundered as inconvenient news surrounding the composer’s activities reached South Korea. These included the performance of Exemplum in memoriam Kwangju in Cologne in 1981 and in other European cities thereafter. Exemplum in memoriam Kwangju commemorated the victims of the Kwangju Massacre – the very brutality that Chun sought to conceal from the beginning to the end of his rule. More broadly, this piece belonged to a series of explicitly political pieces that Yun composed beginning in the late 1970s. Such a new direction was a departure from the generally non-political orientation of Yun’s oeuvre up to this point, an orientation that could provide cover for the idea that Yun Isang was a safe composer who was committed to the idea of Western classical music as “absolute” music devoid of political content. Yun’s politically engaged pieces around this time alluded to dissident and resistance movements in South Korea and beyond. For example, Teile dich Nacht (O Night, Divide, 1980) set to music political verses by Albrecht Haushofer, a member of the resistance movement against the Nazi regime; the second movement of Violin Concerto No. 2 (1983) was written for an antinuclear concert of the Japan Philharmonic Orchestra; Naui Dang, Naui Minjokiyo! (My Land, My People, 1987) was an ode to the peaceful unification of the Korean peninsula and used verses by dissident South Korean poets.66 Besides this activist strand in his works, Yun’s visit to North Korea in 1984 and the establishment of the Yun Isang Research Institute in Pyongyang in 1985 were other inconvenient news. After 1984, the number of performances of Yun’s music dropped again, indicating that they did not pass censorship (see Figure 3).

In this regard, the Chun administration’s bid for Yun may also be understood within the structure of competition between South Korea and North Korea. Kim Il Sung had treated Yun with respect in the 1970s, a period when Yun justifiably saw himself as a victim of South Korean terror. In the early 1980s, Kim continued to court Yun by initiating a number of projects in the composer’s honor. For example, in the same year that the South Korean authorities staged Yun Isang Night, Kim Il Sung established an annual Yun Isang festival, complete with an orchestra devoted exclusively to the performance of Yun’s music.

1988-95: Unwelcome in a “Democratic” Security State

In 1988, Yun took the initiative to take on a more public role involving South Korea. On July 2, he held a press conference in Tokyo to propose a joint North-South concert held near the 38th parallel. This was the composer’s response to the reforms that South Korean society was undergoing as a result of the June Struggle of 1987, the culmination of the democratization movement that had begun in the 1970s. The June Struggle brought forth a popular presidential election for the first time in sixteen years although, ironically, the elected candidate was Roh Tae Woo, a former general who had played a leading role in Chun’s 1980 coup. The new administration, despite limitations, initiated significant departures. Most importantly, it allowed greater freedom of the press. The inauguration of the dissident newspaper Hankyoreh in 1988 was a notable development on this front as it meant the legalization of discourses that had been previously criminalized. Thanks to the influence of Hankyoreh, mention of Yun Isang’s name in news outlets jumped at least tenfold in 1988 compared to 1987. Greater freedom also led to the translation and publication of Luise Rinser’s Der Verwundete Drache in Korean, adding to a rising body of literature that testified to the use of torture during the Park regime.67 Secondly, Roh promised a departure from the confrontational politics of the Cold War. His July 7, 1988 Statement envisioned mutual exchanges between South and North Korea and the end of exhaustive competition, although by 1989 all signs suggested that Roh had no intention of changing the status quo in the state’s dealings with North Korea.

At Yun’s press conference in Tokyo in July 1988, he proposed a Joint National Music Festival involving representative symphonies and choirs of North and South Korea and stated that if the authorities in both countries accepted, he would lead the planning of such an event with civilian organizations from both sides.68 Throughout July 1988, several dozen articles addressed the question of whether the Roh administration would accept Yun’s proposal.69 Initially, the administration did not issue any response, prompting Hankyoreh and a number of musicologists and musicians to urge government action.70 When it finally responded, it became clear that the government had propped up the same fear-mongering ideology of national security of its predecessors (in addition to bureaucratic red tape), in spite of Roh’s July 7 statement and North Korea’s acceptance of Yun’s proposal.71 And establishment newspapers soon reverted to the practice of endorsing the state’s position.

We can trace this process of blocking to a late-July issue of Tonga Ilbo, which published the government’s stance on Yun’s proposal. It stated that the appropriate offices such as the Ministry of Culture, the National Unification Board, and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs would meet to discuss and decide on the question of a joint festival if Yech’ong, a conservative cultural organization, were to accept Yun’s proposal and submit an application.72 By September 1988, it was reported that the festival proposal was withdrawn. A number of reports from October showed that national security bureaucrats had blocked Yun. This meddling, brought up during a congressional hearing in October, was underreported or selectively reported in the press, but when synthesizing different accounts, it appears that the Minister of Foreign Affairs ordered a top National Security Agency (an’gibu) official to pressure the South Korean embassy in Germany to block Yun’s application to contact the Minister.73

Conversations between Yech’ong and Yun resumed in December 1988, but the festival was again suspended by March 1989. This time, the Roh administration and Yech’ong could not tolerate the center-left’s enthusiasm for Yun’s planned visit to South Korea for the festival. The president of Yech’ong, Chŏn Pongch’o, wrote in the March 4 issue of Kyŏnghyang Sinmun that the festival was suspended and blamed Yun for having communicated with a progressive cultural organization (Minyech’ong) and a welcome committee in Kwangju. Chŏn stated that such contacts suggest “a plan with political implications.”74 Another development that the South Korean authorities could not stomach was the performance of Yun’s music in Pyongyang in February 1989.75 Fourteen days after this performance, Kyŏnghyang Sinmun announced that the South Korean government had decided to prohibit the import of records of Yun’s music performed by the State Symphony Orchestra of DPRK, the very orchestra that had played Yun’s music in Pyongyang.76 The dynamics of disinvitation surrounding Yun’s proposed festival suggested that the Roh administration had no intention of allowing South-North exchanges outside its conservative national security channels. Indeed, this posture was reinforced in the course of the 1989, as the state penalized democratization and unification activists who visited North Korea by incarcerating them upon their return to the South.

What is even more remarkable is that the mechanisms of blocking, disinvitation, and state-media collaboration were repeated under the Kim Young Sam administration (1993-8), which touted itself as South Korea’s first civilian democracy. Under the Kim administration, the organization that sought to bring Yun to Seoul was Yeŭm, a classical music marketing firm. In July 1994, newspapers announced that Yeŭm was organizing a Yun Isang Music Festival in September and re-opened the question of the composer’s homecoming.77 Initially, journalists wrote enthusiastically about the prospect of the composer’s return, but soon they presented contradicting information, reflecting the anxieties among national security bureaucrats in the government. Illustrative in this regard was the July 19 issue of Tonga Ilbo, which published contradictory news of Yun’s visit on the same page: one article stated that Yun would come to Korea in August while the article right next to it stated that his homecoming was not confirmed.78 Within a month, Kyŏnghyang Sinmun was casting Yun in an incriminating light, putting the blame on the composer for the cancelled visit in 1989 and underscoring his ties to North Korea.79

Ultimately, Yun did not board the flight that was scheduled to arrive in Seoul on September 3. News articles around this date reveal that the question of Yun’s entry had prompted nothing less than a meeting among bureaucrats in the National Unification Board, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ministry of Culture and Sports, the Ministry of Justice, and National Security Agency, and that it was decided during this meeting that they would not allow Yun’s entry if he did not issue “an apology for his pro-North Korean activities.”80 To communicate this message to Yun, an employee of the South Korean embassy in Berlin went to Yun’s house on August 31 – only three days before the flight – and requested that Yun issue an “official position that he will never engage in political activities” as a condition for coming to South Korea.81 News articles also show that there were irreconcilable stances within the government. Tonga Ilbo reported that the government had “initially decided to disallow Yun’s visit unless he were to issue an apology for his pro-North Korea activities,” but that “the National Unification Board and high-ranking officials” had reversed the initial decision from a “humanitarian standpoint.”82 On the other hand, Kyŏnghyang Sinmun published the Department of Justice’s more aggressive stance that it had not received any entry application from Yun and that it would decide on whether or not to admit him after reviewing his purpose of visit.83 Yun, responding to these messages, indicated through an interview with Kyŏnghyang Sinmun (September 2) that he would board an upcoming flight if the South Korean government made it known that it welcomed him.84 The next day, the Department of Justice announced through Tonga Ilbo that “it absolutely cannot accept Yun’s demand that the South Korean government issue a message of welcome.”85 That was the last message Yun heard from the government via newspapers.

After the failed visit of 1994, the coverage of Yun outside Hankyoreh moved to the familiar practice of advertising recognition of his music in Europe and the United States.86 In November 1995, journalists wrote about Yun’s death in West Germany. Even these reports relied on the established trope of praising Yun’s international standing in contemporary art music while leaving untouched the history of his unjust sufferings under the Park regime.

Conclusion

This article traced the reception of Yun Isang in several mainstream South Korean newspapers from 1952 to 1995 in light of a recurring politics of forgetting that threatened to erase Yun and his sense of duty to justice and peace on the Korean peninsula. In particular, it demonstrated that the figure of Yun was mediated by a persistent tension between ideologies of national security and a desire for national progress in the arts, two defining aspirations of Cold-War South Korea. More broadly, this article explored the collaborative relationship between the media and the state as a productive site of Cold-War “truths,” drawing on scholarship that defines the media-state nexus as an object of inquiry in examining postwar histories of South Korea.

It should be noted that the South Korean reception of Yun after his death changed significantly. With more liberal administrations in power – from Kim Dae Jung (1998-2003) to Roh Moo Hyun (2003-8) – all restrictions surrounding Yun’s works were lifted, and his music was performed much more frequently. To cite one year as an example, in 1999, the opera Butterfly Widow had a South Korean premiere, and Angel in Flame, an orchestral work that memorializes the self-immolation of student activists during democratization protests in 1991, was performed in the most middle-class of classical music events in South Korea, the Seoul Arts Center Symphony Festival. Commemorative projects, such as photo exhibitions, documentaries, and biographical novels, also emerged and culminated in the founding of the Tongyeong International Music Festival (TIMF), a contemporary music festival in Yun’s hometown Tongyeong, in 2002. Nevertheless, these projects did not completely drown out time-tested anti-communist paranoia,87 and Yun’s name became the target of blacklisting again when a conservative government under Park Geun-hye’s leadership came into power in 2013. In 2016, the Park administration cut the budget that had been set aside for the Yun Isang International Music Competition, as part of the administration’s blacklisting and stigmatization of progressive cultural projects and artists.88 Moreover, a number of conservative groups have continued to keep a close watch on developments surrounding Yun, even two decades after his death. In 2018, when Yi Suja, Yun’s wife, came to Tongyeong to bury the composer’s ashes, they staged a series of rallies, demanding that his remains be buried in North Korea.89

The tension that Yun tested for almost three decades is not a closed chapter belonging to South Korea’s illiberal past. This tension continues to police the boundaries of cultural legitimacy, albeit in abated forms, and as long as the National Security Law continues to exist, it will be available as a legal basis for shaping the parameters of cultural and moral legitimacy. Nor is this tension a phenomenon unique to South Korea. It was an identifiable feature of Cold War cultures globally, as shown by the blacklisting of illustrious but dissenting composers, such as Aaron Copland, Leonard Bernstein, Dimitri Shostakovich, and Sofia Gubaidulina, among others. And today, powerful state leaders are grasping onto the seemingly outdated tactic of suppressing dissenting public figures in the name of national security (or, relatedly, “public safety” and “law and order”), whether in the United States or China. In a world that is witnessing a visible return of such oppressive tactics, the story of Yun Isang in South Korea reminds us how national governments with the aid of the media can mobilize the fear of an ideological Other in order to impose their own version of the truth on their citizens.90

Notes

Torture of Yun was not revealed to the South Korean public until a full translation of The Wounded Dragon was published in 1988. Under Park’s rule, journalists who knew about the use of torture could not report it without risking retribution.

“Cheirŭm ch’ajŭn yunisang kinyŏmgwan [Yun Isang Commemoration Hall reclaimed his name],” Hallyŏ t’udei, April 5, 2019.

For example, see Shin-Hyang Yun, Yunisang kyŏnggyesŏnsangŭi ŭmak [Yun Isang, Music at the Border Line] (Paju: Han’gilssa, 2005); Jeongmee Kim, “The Angels and the Blind: Isang Yun’s Sim Tjong,” The Opera Quarterly 17, no. 1 (2001): 70-93. Yun Isang’s musical style has also been one of the most popular dissertation topics among overseas South Korean doctoral students in music performance.

Theodore Hughes, Literature and Film in Cold War South Korea: Freedom’s Frontier (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012), 3.

“Kagŭkkwa yŏnghwaŭmak palp’yoginyŏmhoe [commemorative concert of operettas and film music],” Kyŏnghyang Sinmun, March 3, 1952.

For example, “Han’guk chakkokka hyŏphoe [Korean composers association],” Kyŏnghyang Sinmun, September 19, 1954.

See Luise Rinser and Isang Yun, Yunisang sangch’ŏ ibŭn yong [Yun Isang, the wounded dragon] (Seoul: RH Korea, 2004), 43-7. First published 1977 by S. Fisher.

For example, “Yunisang tobul hwansonghoe [farewell gathering for Yun Isang’s trip to France],” Tonga Ilbo, May 23, 1956.

Martin Iddon, New Music at Darmstadt: Nono, Stockhausen, Cage, and Boulez (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 224.

Amy Beal, New Music, New Allies: American Experimental Music in West Germany from the Zero Hour to Reunification (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2006), 123. Peter M. Chang, Chou Wen-Chung: the Life and Work of a Contemporary Chinese-born American Composer (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2006), 34.

“Sogwanhyŏnakkok sŭk’oŏ kanhaeng [publication of chamber music],” Kyŏnghyang Sinmun, May 21, 1960.

Chunman Kang, Han’guk hyŏndaesa sanch’aek 1950nyŏndaep’yŏn 1kwŏn [a stroll through Korea’s contemporary history, 1950s, no. 1] (Seoul: inmulgwa sasangsa, 2004), 327.

“Haeoeesŏ ttŏlch’in chŏngjin’gongjŏk [overseas accomplishments],” Tonga Ilbo, December 27, 1965; “Sŏdoge ttŏlch’in uriŭmak [our music making a mark in West Germany],” Tonga Ilbo, November 17, 1966.

“Aakkwa hyŏndaeŭmak [Korean court music and modern music],” Kyŏnghyang Sinmun, February 22, 1967.

“Yunisang chakkok kamsahoe 22ilbam [Yun Isang music appreciation event to be held on the evening of the 22nd],” Kyŏnghyang Sinmun, December 21, 1960.

This scholar, Im Sŏkchin, was known in South Korea mainly as a leading scholar of Hegel until his death in 2018. He completed a doctoral degree at the Goethe University Frankfurt in 1961. In 2003, Im testified that his disclosure of some overseas South Koreans’ visit to North Korea was greatly exaggerated by the KCIA. See “Minjuhwa paljach’wi [the traces of democratization],” Han’guk Ilbo, May 30, 2003.

Chunman Kang, Han’guk hyŏndaesa sanch’aek 1960nyŏndaep’yŏn 3kwŏn [a stroll through Korea’s contemporary history, 1960s, no. 3] (Seoul: Inmulgwa sasangsa, 2004), 150-165.

“Tongbaengnim kŏjŏmŭrohan pukkoegongjaktan kŏmgŏ [arrest of North Korea’s East Berlin communist espionage operation],” Kyŏnghyang Sinmun, July 8, 1967.

See, for example, “Pukkoedaenam chŏkhwagongjaktan chŏkpal chŏngbobujang palp’yo [the KCIA’s exposure of North Korea’s communist espionage operation against the south],” Maeil Kyŏngje, July 8, 1967.

For example, “P’yŏngyangdo tanyŏwatta [I even went to Pyongyang],” Kyŏnghyang Sinmun, November 15, 1967; “Kongso kŏŭi siin yunisang [Yun almost admitted the charges],” Tonga Ilbo, November 15, 1967.

From the perspective of the South Korean government, the most damning response was the West German government’s decision to discontinue its aid program toward South Korea. This was not reported in South Korea at the time of suspension. Only when the suspension was reversed did Tonga Ilbo cover the incident. The article commended Park for resolving a foreign relations crisis. “Taehan wŏnjo kŏmt’o chaegae [review of aid program for South Korea reopened],” Tonga Ilbo, March 2, 1968.

Chunman Kang, Han’guk hyŏndaesa sanch’aek 1960nyŏndaep’yŏn 2kwŏn [a stroll through Korea’s contemporary history, 1960s, no. 2] (Seoul: inmulgwa sasangsa, 2004), 329.

“Okchungesŏ yŏkkŏnaenŭn nabiŭi kkum [spinning a butterfly’s dream in jail],” Tonga Ilbo, December 4, 1967.

“Okchungjakkok nabiŭikkum [a butterfly’s dream composed in prison],” Kyŏnghyang Sinmun, December 7, 1967.

“Haoe kuhyŏng kongjaktan hangsosim [this afternoon, the appeal court rules on the espionage case],” Kyŏnghyang Sinmun, March 27, 1968.

For example, “Sŏdok hamburŭk’ŭ yesurwŏn [West Germany’s Hamburg Art Academy],” Kyŏnghyang Sinmun, July 4, 1968.

“Segyeŭi sisŏnmoŭn yunisangssiŭi chakp’um [world’s attention on Yun Isang’s work],” Kyŏnghyang Sinmun, November 13, 1968.

One known case of execution involved Pak Nosu, a researcher at Cambridge University who was visiting Seoul at the time of arrest. He was executed in 1972. In 2017, the South Korean supreme court pardoned Pak and ordered the state to pay 2.3 billion won to Pak’s family. “Sahyŏng 45nyŏnmane [45 years after execution],” JoongAng Ilbo, September 1, 2017.

“Chŏnt’ongjŏgin chubŏp pŏsŏna [going beyond traditional techniques],” Tonga Ilbo, November 20, 1970.

“70nyŏndae munhwagyeŭi cheŏn [recommendations for the cultural community in the 1970s],” Tonga Ilbo, February 17, 1970.

“Sŏul kukche hyŏndae ŭmakche [Seoul international contemporary music festival],” Tonga Ilbo, September 15, 1971.

These included Cello Concerto (premiere in Royan, 1976), Flute Concerto (Hitzacker, 1977), Violin Concerto No. 1 (Frankfurt, 1981), and Clarinet Concerto (München, 1981).

Bonnie C. Wade, Composing Japanese Musical Modernity (Chicago: University of Chicago, 2014), 75-6.

Gavan McCormack, “The Park Chung Hee Era and the Genesis of Trans-Border Civil Society in East Asia,” in Reassessing the Park Chung Hee Era, 1961-1979: Development, Political Thought, Democracy, and Cultural Influence, eds. Hyung-A Kim and Clark W. Sorensen (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2011), 189.

Both groups are still classified as anti-state organizations in South Korea under the National Security Law.

For example, “Panhanhoeŭijangsŏ ch’ungdol [confrontation in an anti-Korean meeting],” Tonga Ilbo, August 15, 1977.

“Ilbonŭn panhanhwaldong kyujehara [Japan should restrict anti-Korean activities],” Kyŏnghyang Sinmun, August 17, 1977.

Sŭnghak Yi, “Sasiriramyŏn ihaehal su ŏpta [if it’s true, I can’t understand it],” Wŏlgan ŭmak (May 1979), 56.

Hongyŏl Yi, “Kugoerago kongsanjuŭie hoŭnghal su ŏpta [even when abroad, one cannot answer to communism],” Wŏlgan ŭmak (May 1979), 57.

Tuhoe Ku, “Ttŏttŏt’i kal kirŭl salp’yŏya ketta [being vigilant in our path],” Wŏlgan ŭmak (May 1979), 57.

Chunman Kang, Han’guk hyŏndaesa sanch’aek 1980nyŏndaep’yŏn 1kwŏn [a stroll through Korea’s contemporary history, 1980s, no. 1] (Seoul: inmulgwa sasangsa, 2004), 108.

“Taehanmin’guk ŭmakche naedal 14il kaemak [Korea music festival to open on the 14th of next month],” Tonga Ilbo, August 20, 1982.

For example, “Yunisangssi akpo 60yŏjong p’anmae [scores of more than 60 works by Yun for sale],” Kyŏnghyang Sinmun, September 13, 1982.

“Han’gugŭi ki yerŭl segyee [Korea’s energy and propriety to the world],” Tonga Ilbo, September 17, 1982.

See Kyongboon Lee, “Yunisangŭi ŭmakkwa p’yŏnghwasasang [Yun Isang’s music and the ideology of peace],” T’ongilgwa p’yonghwa 9, no. 2 (2017): 91-120; Hyejin Yi, “National cultural Memory in Late-Twentieth Century East Asian Composition: Isang Yun, Hosokawa Toshio and Zhu Jian’er,” The World of Music 6, no. 1 (2017): 73-101.

“Yunisang, ruijerinjŏŭi taedam [Yun Isang and Louise Rinser’s conversation],” Kyŏnghyang Sinmun, December 3, 1988.

For example, “Nambukhan haptong ŭmak ch’ukchŏn [South-North joint music festival],” Tonga Ilbo, July 2, 1988.

“Nambuk ŭmakch’ukchŏn chŏngbu ipchang p’yomyŏng ch’okku [urging the government to respond to the South-North music festival],” Hankyoreh, August 24, 1988.

“Nambugŭmakche pukhansŏ surakt’ongbo [North Korea accepts South-North music festival],” Kyŏnghyang Sinmun, July 23, 1988.

“Kŭmmyŏng chŏngbubangch’im kyŏljŏng [the government will make a decision soon],” Tonga Ilbo, July 26, 1988.

“Isunjassi chŭnginch’ulssŏk yogu [Yi Sunja to appear as witness],” Kyŏnghyang Sinmun, October 6, 1988; “Kukchŏnggamsa imojŏmo [the various sides of the congressional hearing],” Hankyoreh, October 7, 1988.

“Nambuk ŭmakch’ukchŏn sasilssang musan [South-North music festival cancelled],” Kyŏnghyang Sinmun, March 4, 1989.

“Yunisangssi sillaeakkok p’yŏngyangsŏ yŏnjuhoeyŏllyŏ [Yun’s chamber music performed in Pyongyang],” Tonga Ilbo, February 13, 1989.

“Pukhan kyohyangaktan yŏnju 4kaeŭmban suip purhŏ [import of four records by the State Symphony Orchestra of DPRK prohibited],” Kyŏnghyang Sinmun, February 25, 1989.

For example, “Yunisang ŭmakch’ukche 9wŏre yŏnda [Yun Isang music festival in September],” Tonga Ilbo, July 12, 1994.

“Yunisangssi 8wŏl han’gugonda [Yun Isang will come to Korea in August],” Tonga Ilbo, July 19, 1994; “Yunssi ‘kwiguk kyŏljŏngandwae’” [Mr. Yun, ‘have not decided on return’],” Tonga Ilbo, July 19, 1994.

For example, “Chomunbangbuk kyop’o nugun’ga [who are the overseas condolence visitors],” Kyŏnghyang Sinmun, July 16, 1994.

“Yunisangssi kwiguk ‘p’yoryu’ [Yun Isang’s return adrift],” Hankyoreh, September 2, 1994; “Yunisangssi kwigukchwajŏl [Yun Isang’s return, frustrated],” Tonga Ilbo, September 3, 1994.

“Ipkukhŏga sinch’ŏng ajik motpadatta [entry application not submitted],” Kyŏnghyang Sinmun, September 1, 1994.

For example, “Orhaeŭi ‘koet’emedal’ chakkokka [this year’s Goethe model recipient’],” Maeil Kyŏngje, March 1, 1995.

For example, the performance of Angel in Flame led to some objections from the classical music community. “Yunisang ‘hwayŏmsogŭi ch’ŏnsa’ kungnaech’oyŏn nollan [controversy over the national premiere of Angel in Flam],” Tonga Ilbo, April 12, 1999.

See, for example, “Yesan sakkam yunisangŭmakk’ongk’urŭ ‘chwach’o’ wigi [budget cut for Yun Isang Competition, under threat of running aground],” Kyŏngnam Ilbo, December 29, 2016.

“Togirŭi yunisang yuhae, 25il t’ongyŏngŭro onda [Yun Isang’s remains to come to Tongyeong after 25 years],” Chosŏnilbo, February 24, 2018.

Research for this article was first presented at a symposium on Yun Isang that was part of the 2017 Tongyeong International Music Festival (TIMF). I thank Dr. Heekyung Lee for inviting me to present at this event.