Abstract: The Technical Intern Training Program (TITP) – a short-term labor rotation system that originated in 1993 – brings young and middle-aged workers from developing countries to Japan with a stated objective to transfer Japanese vocational skills and techniques to these workers. However, the program faced criticism for doing little more than covering the chronic labor shortage in unskilled blue-collar jobs that are regarded unfavorably by many Japanese in recent years. This paper highlights the heightened vulnerability of the technical intern trainees as cheap and disposable sources of labor, especially during the Covid-19 pandemic. Based on digital communications with 16 Vietnamese technical trainees and an analysis of the content on media platforms since the outbreak of the pandemic, the paper extends my previous work on the challenges faced by technical intern trainees, analyzing the handling of Japanese governments and the accepting companies. The article also introduces the roles of support groups in Japan devoted to protecting vulnerable technical intern trainees. At a moment when the Japanese government is reforming and promoting the TITP, this analysis of Vietnamese technical trainees during the COVID-19 crisis is particularly timely.

Keywords: COVID-19, vulnerable populations, technical intern trainees, Technical Intern Training Program, Vietnamese migrant workers

Introduction

On May 1, 2020, the Asahi Shimbun reported the case of a struggling Vietnamese technical intern trainee who had lost his job and was seeking refuge at a temple in Nagoya. In January, after dismissal from a solar-panel manufacturing company in Matsusaka City in Mie Prefecture, he could not find another job and quickly ran out of money (Ko, 2020). The situation is shared by many foreign laborers on short-term contracts since the arrival of COVID-19, but particularly for technical intern trainees, it is just the tip of the iceberg.

On July 8, 2020, the Vietnamese Consulate in Fukuoka officially announced that 47 Vietnamese trainees tested positive for Covid-19 in Nagasu, Kumamoto. The contracted individuals are among the 245 Vietnamese technical intern trainees hired to work at Ariake shipyard. The cluster of infections forced the company to close its shipyard to implement safety measures (“47 Vietnamese trainees,” 2020). So far, this has been the only public recognition of any infection among the trainees.

What remained unexplained in both articles was the very limited options afforded to the technical intern trainee by virtue of their contract status that often put them at risk. Even though he was in a governmental program, he was easily fired when the Japanese employers decided he was too expensive to keep during this time of economic stress. Much like other technical intern trainees, he had accumulated no savings while working in Japan. In addition to a meager salary, generally 900 yen per hour (156,900 yen per month pre-tax on average), which some 60% of hiring companies do not even pay (Nikkei 2019), most trainees have to remit money every month to repay the debt incurred to the recruitment broker in their home country in order to secure a spot in the Technical Intern Training Program (TITP). Trainees cannot apply for unemployment insurance due to the complicated requirements and procedures. If a trainee flees the program, like 9,052 other trainees who fled to escape unfavorable working conditions and abusive employers (Ministry of Justice, 2019), he might secure a better-paying job. But he would lose legal protections. Furthermore, for the many trainees whose passports have been confiscated illegally by hiring companies in order to keep the trainees working at these jobs, they cannot go home even if flights were available. And almost everyone would face difficulties affording plane tickets due to limited savings.

This essay focuses on how the COVID-19 pandemic is affecting the lives of Vietnamese trainees who came to Japan under the Technical Intern Training Program (hereinafter referred to as TITP), or in Japanese, 外国人技能実習制 (gaikokujin jisshusei). The Japanese government has coordinated the TITP since 1993 to bring young and middle-aged workers from developing countries to Japan. This growing segment of foreign low-skilled workers has been brought in largely to help cover the chronic labor shortage in unskilled blue-collar jobs that are unattractive to many Japanese. The present study is the first to interview technical intern trainees while they are still in Japan, rather than after return to their home country. The perspectives of current trainees in Japan are crucial for providing up-to-date accounts of the TITP, while the trainees are still in the program. This research strategy has allowed the author to capture the real-time reactions of technical intern trainees since the start of the COVID-19 outbreak.

Even before the outbreak of the epidemic, the TITP had faced criticism for being an exploitative program. As the COVID-19 epidemic continues to wreak havoc on Japanese society and economy, this research will be able to highlight how COVID-19 has amplified the struggles of foreign trainees.1 This paper presents the results of both direct digital communications with 16 Vietnamese technical trainees, and a summary of the available information found on social media platforms. The author analyzes the impact of COVID-19 while drawing attention to the vulnerable population of trainees caught by circumstances of the pandemic, policy restrictions, and negative attitudes toward foreign workers in Japan.

An overview of foreigners’ emigration to Japan

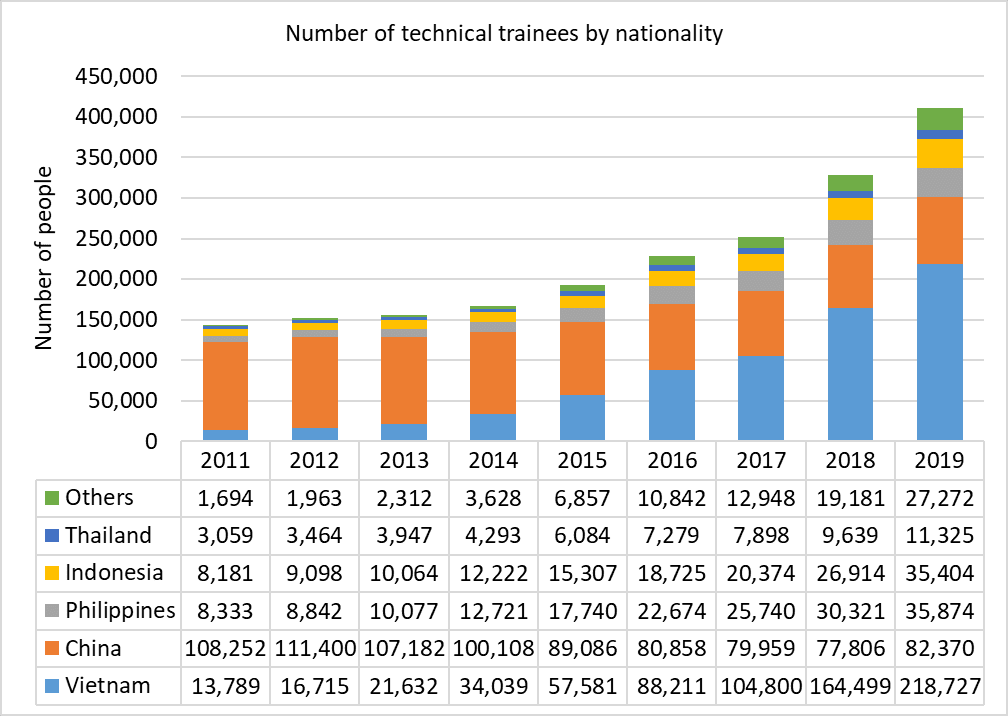

Japan has recently witnessed a significant influx of foreign citizens entering the country. According to a status report by the Ministry of Justice (MOJ), by the end of 2019, the number of “Technical Intern Trainee” visas for all countries was 410,972, an increase of 25.2% over the preceding year (MOJ, 2020). Technical intern trainees comprised 14% of the total number of foreign residents in Japan (MOJ, 2020). Figure 1 presents a breakdown of the technical intern trainees by nationality (MOJ, 2020).

|

Figure 1: Composition of technical trainees (by nationality) 2011-2020. Data from the Ministry of Justice (MOJ, 2020) |

Since 2013, Vietnam has been the fastest-growing country in terms of sending trainees to Japan. With a total of 218,727 people by the end of 2019 (MOJ, 2020), Vietnamese technical intern trainees account for more than 51% of the total number of TITP trainees. Vietnamese trainees are mainly hired in 3 industries: construction (23.3%), food-related manufacturing (20.6%), and machinery and metal (18.6%). The other industries are agricultures (7.7%), textile (6.2%), fisheries (0.5%), and others (2.1%) (OTIT, 2019).

The TITP was created in 1993 to train young and middle-aged people from developing countries as interns in Japan. The program is currently supervised by the Organization for Technical Intern Training (OTIT), which was established in January 2017 and operates under the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare (MHLW). The main objective, as stated in the “Operations Manual for Sending Organizations” by the Japan International Technical? Corporation Organization (JITCO) – the former authorizing foundation of the program – is:

… to contribute to the fostering of talented individuals who can play leading roles in the development of their countries’ industries and economies by accepting young and middle-aged workers from developing countries as interns at industries in Japan and thereby transferring technical skills, technology, and knowledge (hereinafter, the “skills”) developed and cultivated in Japan to the respective industries in the technical intern trainees’ home countries… (JITCO, 2007, p. 3)

As of April 2016, the labor market for technical trainees included 133 specific duties in 74 job categories across different industries including agriculture, fisheries, construction, food manufacturing, textiles, machinery, metal industries, and others (MOJ, 2017). For example, trainees in machinery and metal industries cover tasks related to casting, forging, machining, and metal press. The Operations Manual compiled by JITCO states that the more advanced skills that technical intern trainees acquire must not be gained just through repetitive tasks. Under the new Immigration Control Act, technical intern trainees may extend their stay for up to five years, provided they pass the National Trade Skills Test and meet the requirements of the Regional Immigration Bureau. After the intended period of training in Japan, technical intern trainees are expected to return to their home country and utilize the skills they obtained. In a 2018 survey of 19,468 trainees who had finished the program, 98.2% of respondents reported finding the skills acquired from the technical intern training to be “useful.” Among these, 75.3% of the respondents answered that they specifically found “technical skills acquired” to be useful, followed by “experience living in Japan” (68.5%) and “Japanese language skills upgraded” (68.3%) (OTIT, 2019).

However, the findings from the author’s in-depth interviews with 23 current technical intern trainees differ significantly from the survey data results, so much so as to call into question the conclusions of the OTIT report and the efficacy of the program as a whole. First, even though the interviewed trainees found the skills acquired useful, they also expressed doubt and uncertainty about both their post-TITP career plans and the likelihood of their being able to utilize the skills and knowledge they acquired in Japan upon return to their home country. In other words, the link between the job training conducted in Japan and the potential career plan afterwards is vague. Based on their own experiences and knowledge of others who had been in the program, few saw any future occupational advantage from the technical skills acquired in Japan. Second, while the survey data listed the “usefulness of the living experience in Japan,” it offered no explanation regarding what this meant. The author noted that while technical intern trainees spoke positively about the opportunity to experience Japanese culture and society, they also stated that living in Japan was not as rewarding as they had thought it would be. Many experienced minimal professional development, poor treatment at the hands of Japanese employers, and social exclusion. Third, the survey data is correct to claim that the TITP provided upgraded Japanese language knowledge. However, the author found that technical intern trainees usually only developed Japanese language skills required for the most rudimentary situations and tasks. The simple and repetitive nature of the jobs rendered it unnecessary to acquire more advanced language proficiency and precluded the sort of language development that would allow them to function effectively in a Japanese workplace. The contrasting data suggests that the TITP barely fulfills its stated objective of making international contributions of personnel training, a fact that the report obscures. In fact, as others have pointed out in the past, even after current reforms, the acceptance of foreign low-skilled workers in Japan only helps Japan to cover the chronic labor shortage in blue-collar jobs that Japanese people themselves decline to perform. While this has long been true, the current pandemic has brought this fact into more explicit focus.

Stakeholders involved in the TITP

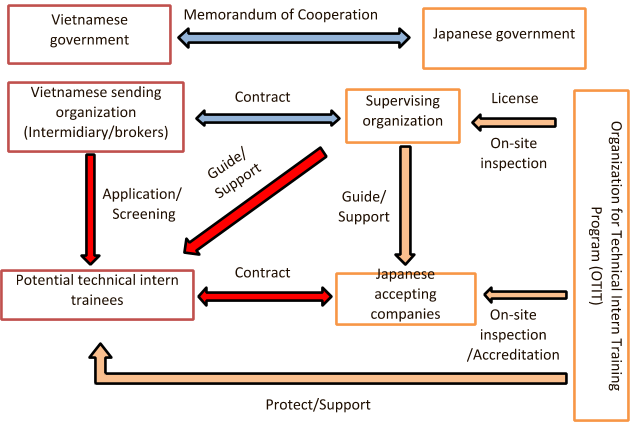

Various stakeholders inside and outside Japan are engaged in the TITP. The process started with official cooperation under the “Memorandum of Cooperation” (MOC) between the governments of Japan and the country sending participants. Apart from Vietnam, the Ministry of Japan has a MOC with 13 other Asian countries, including Cambodia, India, the Philippines, Laos, Mongolia, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Bhutan, Uzbekistan, Pakistan, Thailand, and Indonesia (MLHW, 2020).

Technical trainees are first connected to Japanese corporations through the broker system and sending organizations in Vietnam, and then a supervising organization in Japan. The sending organization first filters candidates to match the job postings. The recruited trainees then sign a contract with the Japanese company and complete a visa application. Once the trainees arrive in Japan, under the management of the supervising organization, they then start working at the host companies (accepting companies) with which they have already signed contracts. Figure 2 shows the web of connections and the roles of each stakeholder.

|

Figure 2: Roles of each stakeholder in the TITP and the relationships between them. Data adapted from the Ministry of Justice (MOJ, 2017) |

Difficulties as technical trainees in Japan

Research on technical trainees has primarily focused on the workers’ experiences in Japan, a situation plagued by a lack of rights and protections. Lee (2011, p. 122) pointed out that as “trainees” they are not “not protected by the labor laws regulating ‘workers.’” Generally, temporary labor migrant workers have limited rights and “are often construed by employers and governments of receiving countries as cheap, flexible, and disposable labor” (Belanger & Tran, 2013, p. 7). In 2018, the OTIT reported 4,707 cases of accepting companies violating technical intern trainees’ rights (OTIT, 2018). These instances of misconduct include illegal training implementation, an underprepared training system, the lack of a benefits system, the lack of books and document provisions, the submission of false documents to legal authorities, and lack of protection of technical trainees. My current research reveals that many of these problems persist.

Financial Problems

First, migrant rights can be threatened by networks of intermediaries and recruitment agencies before they even arrive in Japan. Given their roles as intermediaries between employers and job seekers, brokers can exploit candidates by overcharging them for their services when people are seeking migration opportunities (Belanger & Wang, 2011, p. 39). These excess charges often include recruitment fees, pre-departure training fees, and deposit fees as a way to prevent trainees from “running away.” For this reason, Vietnamese technical trainees going to Japan have to secure loans from various sources; in most cases, they even have to mortgage their assets. Having to pay an exorbitant pre-departure fee is common in many Asian countries. Still, migrant workers headed for Japan usually pay the highest fees compared to those headed to other Asian countries (Belanger & Tran, 2013, p. 13), with fees ranging between 5,000-9,000 US dollars. The technical trainees are still willing to spend this amount for a chance to gain a ticket to what they believe will be the “privilege” of working abroad, especially in Japan.

Second, the literature emphasizes the inadequate salaries as one serious difficulty that causes trainees to leave their companies and seek higher wages through illegal work. The lack of overtime opportunities, and sometimes low pay for overtime work, makes it harder for trainees to repay their debts. Since the trainees are not allowed to work overtime by law, they have become accustomed to working overtime for low wages for fear of violating the terms of the program (Belanger, Ueno, Hong & Ochiai, 2011, p. 46). In 2019, the Japan Times reported the results of an investigation of Japanese enterprises that hire technical intern trainees (Magdalena, 2019 March 29). Out of 759 cases of suspected abuse, 231 interns failed to receive overtime wages for overtime work, and 58 others were paid below the legal minimum.

Furthermore, the author’s research is consistent with previous research that shows Vietnamese technical intern trainees’ responsibility to send money to their home country. The amount of remittance typically ranges from 80,000-100,000 yen per month and is used to repay the debt incurred from their pre-departure fees, and to financially support their family. On average, a trainee would earn around 130,000-150,000 yen (approximately 1,300-1,500 US dollars) per month after taxes and rent. Given their high remittance payments, many technical intern trainees barely manage to pay for food and daily necessities with their salaries. G.H., a male trainee at a machinery company, recounted his struggle with balancing the monthly wage of 120,000-130,000 yen:

It is a bit different from what I imagined. When I signed the contract, the salary shown was higher than what I am getting now. The gap, of course, depends on the amount of overtime work, etc. I can only save if I set a strict budget on living expenses.

Surprisingly, the current amount of remittance has not changed much compared to previous studies. Research conducted in 2010 found that Indonesian technical intern trainees also sent around 80,000-120,000 yen home every month (Nawawi, 2010) but most of that money will usually be used to repay debts accumulated before leaving. Considering the lack of transferable skills that are attained, most technical intern trainees’ primary goal is to make money, a goal that is hardly achievable with the current situation.

Non-financial Difficulties

The research also highlights the non-financial difficulties that the trainees face. Belanger, Ueno, Hong & Ochiai (2011, p. 44) point out that the TITP system lacks opportunity for labor mobility, since trainees are legally tied to their first employer. Companies often threatens workers with deportation if they request to transfer to a different company. Second, trainees are often subject to abusive working conditions. Belanger & Tran (2013, p. 14) reported that technical trainees are most likely to endure verbal abuse, followed by physical abuse, from Japanese employers. Additionally, some trainees have reported being put under strict surveillance from their company. Belanger, Ueno, Hong & Ochiai (2011, p. 47) highlighted extreme cases of passport confiscation, or harsh punishments for minor offenses such as “forbidding trainees from having contact with the outside world,” “not allowing workers to go shopping or meet with friends,” and “sending back workers because they let friends stay over,” among others.

Unfortunately, these practices seem to be continuing. A 24-year-old Vietnamese technical trainee testified at a press conference on March 14, 2018 that he had been assigned radioactive clean-up work in Fukushima. The Japan Times reported that under the contract signed with the Iwate Construction Company, the trainee was to learn skills related to construction machinery, demolition, and civil engineering. However, the trainees ended up being assigned decontamination tasks in the residential areas around the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant, the site of a 2011 earthquake, tsunami and nuclear meltdown (Suk, 2018 Oct 19).

The author’s research on Vietnamese technical intern trainees substantiates the previous findings regarding violations, while further highlighting the trainee’s Japanese language insufficiency as a factor in non-financial hardship. Having limited or no Japanese language skills with which to communicate, technical intern trainees run a heightened risk of labor abuse. This also prevents them from seeking help from legal entities if they experience such abuse. Additionally, poor language ability often results in trainees making mistakes, which in turn creates increased tension between Japanese staff and trainees. (The trainees study Japanese language before arriving in Japan but the type of language education does not prepare them to communicate with their Japanese bosses or co-workers.)

Despite revisions to the TITP program in 2010 and 2017, these problems have persisted. In 2010, the program was revised under the new Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act to officially establish a “technical intern training” visa and recognize technical intern trainees as eligible “workers.” In recognition of the continued problems, in 2017, a reformed Technical Intern Training Act created stricter regulations regarding the licensing system of sending agencies, supervising companies, and accepting companies, the mechanism for reports and penalties against violations, and created a legal entity in the Organization for Technical Intern Training (OTIT) for management and on-site inspections of the program.

Revision of the law related to TITP in response to COVID-19

In response to increasing difficulties faced by technical intern trainees as a consequence of COVID-19, the Immigration Services Agency of Japan has temporarily revised the program with the following main changes:

- Technical trainees with expired visa status who are unable to return to their home country will be eligible to change the status of residence to “Designated Activities.” This 6-month visa permits technical trainees to continue working at the same organization as before if allowed to do so (MOJ, 2020).

- Technical trainees who have lost their jobs can change to a new employer through “a matching of the Japanese government with a recruitment agency.” The new system makes possible reassigning unemployed technical trainees to other enterprises that are currently understaffed. Jobless technical trainees may work in various industries for a period of one year (MOJ, 2020).

Apart from the legal changes, technical intern trainees who are registered in the Basic Resident Register as of April 27, 2020 are also eligible for Japan’s COVID-19 100,000-yen payment. However, strict rules regulating these payments also mean that trainees whose visas expired before April 27 are excluded from the cash relief plan (Toshiki, 2020).

Media representation of Technical Intern Trainees under Covid-19

The mainstream media has run increased numbers of stories concerning technical intern trainees since the beginning stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Major newspapers focused heavily on three specific issues that emerged due to COVID-19. First, foreign technical trainees are especially prone to being laid off. Second, limitations imposed by immigration regulations frequently make it impossible for trainees with expired visas to return home. These first two issues primarily arose within generally sympathetic treatment of the difficult situations encountered by the trainees during the shared hardship of COVID-19. The third issue is different and more common. It examines the technical intern trainees as a primary source of labor, whose absence is creating labor shortages for Japanese companies. Strict border controls have prevented accepting companies from securing the necessary workforce of potential technical intern trainees who had previously signed an employment contract and had an intended date of arrival in Japan.

The majority of articles report simply on labor shortages, lament that “…industries such as agriculture and nursing care face labor shortages as new technical intern trainees cannot travel to Japan” (“Unemployed foreign tech,” 2020). The Japan Times and The Mainichi examined the issue of labor supply while focusing on the situations of specific Japanese industries due to the expansion of COVID-19 and the late arrival of expected technical intern trainees. The Japan Times stressed the economic importance of the trainees by giving an example of local lettuce farmers in Nagano prefecture. “Manpower is needed during the lettuce harvest season starting in mid-May,” said a prefectural official in charge of farming promotion. Without sufficient workers, “farmers will end up disposing of their products.” (“Japanese businesses hit,” 2020). The portrayal of news media clearly shows that the TITP acts as a state-sponsored source of labor for small and mid-size Japanese enterprises. Both of these examples document the labor situation from the point of view of the accepting companies, substantiating the view that the acceptance of foreign low-skilled workers in Japan significantly reduces the chronic labor shortage.

On the other hand, The Nikkei Asian Review has often run stories sympathetic to the vulnerability of technical intern trainees who lost their jobs. For example, one story reports that “in a growing number of cases, employers squeezed by the COVID-19 outbreak have taken advantage of trainees’ poor Japanese-language skills and lack of legal knowledge to force them to end their contracts” (Matsui & Asakura, 2020). Similarly, Reuters also recognized that “foreign workers are particularly vulnerable, with a weaker support network and language barriers that prevent them from seeking government help.” (Murakami, 2020). The Asahi Shimbun also showed strong support for the technical trainees, stating that “they deserve to receive policy support [for switching jobs]” (Murakami, 2020).

Additionally, the Nikkei and Asahi voiced skepticism about the new policy allowing technical trainees to switch jobs. While the Nikkei expressed doubts, saying that “[as] this measure requires both the trainee and the original employer to be involved in the job search, it remains unclear whether the system will work” (Matsui & Asakura, 2020), the Asahi called for stricter regulations from the Japanese government by offering suggestions like this:

Only employers who have not committed any related violation in the past and pledge to abide by the rules should be eligible for the government’s emergency job-placement service. It should be ensured that all these procedures and principles for the service will be observed. (“Editorial: Allowing jobless foreign,” 2020)

Doubts about the feasibility of the revised policy raised in the two newspapers underlined how the TITP’s current system has allowed stakeholders (Japanese accepting companies, supervising companies, etc.) to violate the rights of technical intern trainees repeatedly and often without consequence. In general, the findings in Japanese news articles correlate those of previous academic research. Japanese employers are remarkably dependent on foreign technical intern trainees, while regarding the trainees themselves as cheap and disposable, leading to their being the first to be terminated due to this ‘COVID-19 recession’.

This study primarily drew on data from online interviews with technical intern trainees and content found on SNS such as Facebook. Due to social distancing protocols, the author was unable to conduct face-to-face interviews with technical intern trainees and organizers of support groups.2

Primary Findings

Increasing anxiety over health

Despite being alerted to the increasing number of infections in Japan, most trainees still have to continue with work as usual.

As I have to travel to different locations, I am terrified of getting affected. But I have no choice but to go to work. I started wearing masks for my own safety.

— A male trainee from a home interior installation company

Even though I worry about possible infection, I still have to finish my work. We, trainees, are not even allowed to have days-off. There’s nothing we can do about it.

— A male trainee from a water-proofing company

Because of increased risk of COVID-19 infection, the amount of support from the companies affects the trainees’ ability to work. Some employers implemented protection measures, while others did not.

My company provides alcohol-based hand sanitizers and masks for employers. We are also asked to take our temperature before going to work. As I heard that my current area is also high in terms of infection cases, I feel more protected thanks to the company’s measures.

— A female trainee from an industrial packaging company

I still have to commute to work by train every day. Even during the pandemic, the train stations are still crowded as usual. My company did not give me any protection mask, either. It’s scary.

— A male trainee from a construction company

I have to buy my own masks. This corona situation is freaking me out. I don’t know where to seek help if I get infected.

— A male trainee from a construction company

A striking finding emerging from these narratives is that even though all respondents voiced anxiety over being exposed to infection, none really expressed anger at the failure of the companies to protect them. The trainees’ resilience in the face of high-risk work, and the company’s frequent neglect of safety measures, implies the importance for trainees of keeping their job and their fatalistic attitudes toward personal risk. That the trainees had no other choice but to persevere with daily tasks connects with the next theme of financial risk.

Increased financial risk

In general, trainees in all industries suffered from reduced working hours and a lack of overtime work during the pandemic. As the majority of trainees are paid hourly, the sudden reduction in workload had a considerable impact on their wages.

My job is significantly affected by COVID-19. I had been getting a lot of days off even before Golden Week. At my place, there is no money pay if you do not work. This month I am only working several days. I guess that can only cover the house rent.

— A male trainee from a metal and machinery company

Those trainees in agriculture have been least affected. The following account is from a trainee whose visa expired in April, but was able to secure her current job after visa renewal:

My visa expired last month, and I was supposed to go home. But the company extended my visa for three months. We are still able to work as usual. It’s lucky for us to work in a food company.

— A female trainee from a seaweed processing company

However, not all trainees with expired visas can continue their employment in the same way. A male trainee from a machinery and metal company obtained a 3-month extension but was unable to secure employment due to a sharp decline in orders. He stated:

I am really frustrated. I have been spending almost my entire salary, but I’m still unable to go back to Vietnam. And people with expired visa status like me are not eligible for the 100,000-yen grant.

— A male trainee from a machinery and metal company

As reported in the Japanese press, there are also trainees with growing stress regarding financial stability due to their delayed return to Japan.

I [was] supposed to return to Japan for another 2 years starting in April, but I am still stuck in Vietnam due to flight cancellations. It’s good to be with my family a little bit longer, but I will not be able to earn a living if the current situation persists.

— A male trainee from a machinery and metal company

The above quotations illustrate the financial struggles which have been exacerbated by the outbreak of COVID-19. Intern trainees who were already pressured financially now find it even harder to make ends meet in Japan. The same applies to technical trainees who are caught in the middle of flight cancellations due to heightened border control.

Lack of information

Technical trainees also generally lack access to official information regarding COVID-19 due to the language barrier. The Japanese government has attempted to publish announcements and establish consultation hotlines that support trainees’ mother tongues, but not all technical intern trainees can reach the support systems, since they must also grapple with the lack of available operators and complicated search procedures. As a result, technical intern trainees have been using shared SNS platforms to try to gain information and express their concerns.

One common concern was that trainees were receiving no official announcements from their employers regarding the government’s 100,000 grant payment:

I am really confused about this system. Some of my friends said that the supervising company and accepting company would support us with the grant application. On the other hand, some said that we have to wait for the documents and fill them out on our own.

— A female trainee (unknown industry)

The uncertainty over whether the company would grant partial salary payment during a business shutdown is another concern for technical trainees who are temporarily out of work.

I have never heard anything about the partial salary payment system. Before, if we got a week off on the New Year holidays, the company would give us 3 paid days off. I am not sure how they will pay us. I assume that we will receive money only if we work. I am frustrated seeing my salary slip.

— A male trainee from a construction company

One trainee voiced this opinion regarding Japan’s preventive measures:

All I can see, and I guess other Vietnamese living in Japan as well, is Japan’s indifference, coldness, stagnation, and helplessness in dealing with this corona situation. We feel worried and infuriated with the current situation here. Apart from implementing social distancing, we can only count on luck.

— A male trainee from a construction company

The technical intern trainees’ attempts to request assistance on social media platforms demonstrates their vulnerability and weak support networks. The supervising companies and accepting companies, which are supposed to be responsible for the trainees, pay little or no attention to the anxieties of their employees.

Desire to go back

Many of the technical trainees currently working expressed a desire to travel back home.

I desperately want to go back to Vietnam. I cannot believe in the Japanese government and the people anymore. My company is still working as usual as if nothing has happened. They regard this severe pandemic as a harmless flu.

— A male trainee from a construction company

Nevertheless, as the COVID-19 pandemic spread, stricter regulations on immigration were imposed to slow the spread of infection. In the case of Vietnam, major airline carriers stopped their services near the end of March 2020, shattering the trainees’ hopes to return.

Our group scheduled our first return flight on March 30th. Since then, our supervising company has tried to rebook our tickets six times, but could not. People who are not in the same situation as us would never fully understand. I hope that outsiders would not give any further personal comments on Facebook regarding this situation. That only makes us feel more depressed.

— A male trainee from a metal and machinery company

As per the employment contract, trainees who finished their employment term were supposed to be eligible for return plane tickets funded by their accepting companies. However, when all airlines suspended their commercial flights, the only hope for technical intern trainees to return home was to register for special flights coordinated by the Vietnamese government. The objective was to repatriate Vietnamese citizens who were in critical condition but unable to return. Apart from technical intern trainees, the sick, pregnant women, and some students who had expired visas were prioritized. Given the considerable gap between the demand for return tickets and the limited flight schedule (only 1-2 flights per month), technical intern trainees had slim hopes of making it onto a flight, and many had to pay their own way on international flight themselves.

Reaching out to support groups

|

Vietnamese trainees asking for help in front of Vietnamese embassy in Tokyo, Japan. |

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, various support groups and organizations had advocated for foreign technical intern trainees in Japan because of the already inadequate support provided by the Japanese government. Especially due to COVID-19, global support groups such as the “Clean Cloth” labor union expressed concerns over the COVID-19 outbreak and the “severe health risks to the migrant workers” and called for revisions to the TITP (Clean Cloth, 2020). Meanwhile, individuals like Zhen Kai, who runs a shelter for technical intern trainees fleeing Japanese enterprises, continue to assist foreign trainees in battling labor violations and human-rights abuses.

Additionally, several grassroots groups within Japan realized that foreign citizens struggling financially in Japan have found themselves in need due to income loss. One response to this is the charity called “A Rice Bowl of Love” (Chén gạo tình thương /一杯の愛のお米プロジェクト). In early April, a group of Vietnamese Christian priests and sisters decided to raise funds to send out aid packages to struggling Vietnamese community in Japan. Father Nha, a priest at St Ignatius Church in Yotsuya in Tokyo, explained the goals:

On the very first days of April, after the Japanese governments announced the emergency in several cities, I started wondering, “What will happen to Vietnamese youths living in Japan that do not have enough money for food.” I worry about them because Vietnamese technical intern trainees send the majority of their monthly salary back home. They probably do not have enough savings.

Father Nha reached out to other Vietnamese priests and sisters to support his project. The details were announced on Facebook on April 9, 2020, and since then, the organizers have sent over 2,600 bundles of food items (rice, seasonings, packaged food, etc.) and masks to struggling Vietnamese. Father Nha added that “we hope to be able to send a message to the Vietnamese community that they are not alone in Japan.”

Regarding the Japanese government’s grant payment policy towards foreign people in Japan, Father Nha commented:

I have not seen any discriminatory treatment toward foreign citizens. As long as foreign citizens legally reside in Japan, they will be able to receive the same grant. Nevertheless, the amount of grants is still relatively limited compared to the general expectation. We are hoping to see more aid policies to cover rent, tuition reduction, etc.

In short, while waiting for the Japanese government to find solutions that benefit all involved stakeholders, such groups have provided support that technical intern trainees desperately need.

Conclusion

Amidst the outbreak of COVID-19, the Japanese government has made numerous attempts to provide financial, employment, and health support to foreign technical trainees. However, these measures have not reached all the trainees. There is a visible gap between the Japanese government’s ideal policy and the reality of that policy, threatening the livelihood of technical intern trainees. The reality is that the accepting and supervising companies are still the main stakeholders, and they bear the primary responsibility for the technical trainee interns since they are the primary beneficiaries of the cheap labor. Most of these companies have become reliant on foreign labor, yet in times of economic difficulties, many turn a blind eye to these short-term contract laborers, laying them off first and not addressing their increasingly desperate situation. As a result, technical intern trainees, who are already vulnerable and struggle with unstable finances and precarious jobs, are further exposed to danger during this global health crisis.

From the start of their application until their training period in Japan ends, the trainees are susceptible to deception and abuse. The COVID-19 pandemic has only exacerbated the precariousness of the technical intern trainees. As increasing numbers of aspiring trainees seek employment opportunities in Japan, the need for more vigorous enforcement of the TITP deserves closer attention from Japanese policymakers.

References

Bélanger, D., Ueno, K., Hong, K. T., & Ochiai, E. (2011). From Foreign Trainees to Unauthorized Workers: Vietnamese Migrant Workers in Japan. Asian and Pacific Migration Journal, 20(1), 31–53.

Bélanger, D., & Linh TRAN GIANG. (2013). Precarity, Gender and Work: Vietnamese Migrant Workers in Asia. Diversities, 15(1), 5–20.

Clean Clothes Campaign. (2020). Made in Japan Report. Accessed May 2020.

EDITORIAL: Allowing jobless foreign interns to switch jobs must be only a stopgap. (2020, April 30), The Asahi Shimbun.

Gaikoku hito no chingin jittai haaku 19-nen chōsa kara kōrōshō [Understanding the actual state of wages of foreigners in 2019 – a survey from Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare] (2019, May 27), The Nikkei Shimbun.

Japanese businesses hit by lack of Chinese trainees amid virus outbreak (2020, March 20), The Japan Times.

Japan International Training Cooperation Organization (JITCO). (2010). Technical Intern Training Program: Operative Manual for Sending Organizations. Accessed May 2020.

Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. (2018). Ginō jisshū ni kansuru nikuniaida kiritome (kyōryoku oboegaki) [Bilateral Agreement on Technical Internship (Memorandum of Cooperation)]. Accessed May 2020.

Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. (2020). Gaikokujin rōdōsha no chingin [Wages of foreign workers]. Accessed May 2020.

Japan’s Ministry of Ministry of Justice. (2017). New Technical Intern Training Program. Accessed May 2020.

Japan’s Ministry of Justice. (2018). Chōsa kentō kekka hōkoku-sho [A Report of Survey/Study Result]. Retrieved in May 2020 from

Japan’s Ministry of Justice. (2019). Heisei 30 nenmatsugenzai ni okeru zairyū gaikoku ninzū ni tsuite [Number of foreign residents in Japan as of the end of 2018]. Accessed May 2020.

Japan’s Ministry of Justice. (2020). Guide to Support for Continuous Employment for Foreigners Who Have Been Dismissed, etc. Accessed May 2020.

Japan’s Ministry of Justice. (2020). Reiwa gannen nenmatsugenzai ni okeru zairyū gaikoku ninzū ni tsuite [Number of foreign residents in Japan as of the end of the first year of Reiwa]. Accessed May 2020.

Japan’s Ministry of Justice. (2020). Shingata koronauirusukansenshō no kansen kakudai-tō o uketa ginō jisshū-sei no zairyū sho shinsei no toriatsukai ni tsuite [About the handling of residence permit applications for technical intern trainees who have been infected by the new coronavirus infection]. Accessed May 2020.

Jesuit Social Center Tokyo. (2020). Kifu no onegai (ippai no ai no o Amerika purojekuto) [Donation Request (A rice bowl of love)]. Accessed May 2020.

Ko, A. (2020, May 11). Vietnamese find lifeline at temple in Nagoya after losing jobs. The Asahi Shimbun.

Lee, Y. (2011). Overview of Trends and Policies on International Migration to East Asia: Comparing Japan, Taiwan and South Korea. Asian & Pacific Migration Journal (Scalabrini Migration Center), 20(2), 117–131.

Nawawi, N. (2010). Working in japan as a trainee: the reality of indonesian trainees under japan’s industrial training and technical internship program. Jurnal Kependudukan Indonesia, 5(2), 29–52.

Magdalena, O. (2019, March 29). Probe reveals 759 cases of suspected abuse and 171 deaths of foreign trainees in Japan. The Japan Times.

Matsui, M. & Asakura, Y. (2020, May 9). Foreign workers left high and dry in Japan’s coronavirus economy. Nikkei Asian Review.

Murakami, S., (2020, May 5). Foreign workers feel the pain of ‘corona job cuts’ in Japan. Reuters.

Organization for Technical Intern Training (OTIT). (2019). FY2018 Technical Intern Trainees Follow-up Survey (Summary). Accessed May 2020.

Organization for Technical Intern Training (OTIT). (2019). Heisei 29-nendo Heisei 30-nendo gaikoku hito ginō jisshū kikō gyōmu tōkei gaiyō [FY2017/2018 FY Foreign Skills Training Organization Business Statistics Summary]. Accessed May 2020.

Organization for Technical Intern Training (OTIT). (2019). Jisshū jisshi-sha ni okeru omona ihan shiteki naiyō betsu kensū [Number of major violations by accepting companies]. Accessed May 2020.

Phan, A. (2020, May 14). Vietnam to bring another 4,300 citizens home on special flights. VNExpress International.

Suk, S. (2018, October 19). Four Japan firms used foreign trainees to clean up at Fukushima plant after nuclear meltdowns: final report. The Japan Times.

Taking a Stand: Gifu Labor Union Fights to Protect Foreign Technical Trainees in Japan (2020, April 20), The Nippon.com.

Thanh niên Việt thất nghiệp tại Nhật: “Xin cho chúng cháu về nước.” [Unemployed Vietnamese youth in Japan: “Please send us home.”] (2020, July 10), Nghiep Doan Bao Chi.

Toshiki, H. (2020, May 22). Cash handout program to cover foreign trainees stuck in Japan. The Asahi Shimbun.

Unemployed foreign tech interns in Japan to be allowed to switch jobs (2020, April 17), Kyodo News.

47 Vietnamese trainees test positive for COVID-19 in Japan (2020, August 5), Voice of Vietnam.

Notes

The author has been researching the status of TITP trainees, especially Vietnamese technical intern trainees in Japan, for two years as part of the requirements for the M.A. degree in Japanese Studies at Sophia University in Tokyo.

The data presented in this paper was drawn from individual chat messages with 16 technical intern trainees (14 males, 2 females) from Tokyo, Saitama, Chiba prefecture, and Vietnam. The interviews were conducted in Vietnamese, presented here with English translations by the author. The interviewees all possess legal training on visa status and are between the ages of 20 and 30. They have been working or are expected to work in agricultural, machinery and metal, industrial packaging, or construction sectors. The study does not identify individual names to protect their identities.