Abstract: This essay revisits the 1946-7 “Politics and Literature Debate” (Seiji to bungaku ronsō), a pivotal controversy among leftist Japanese writers and intellectuals that is conventionally cited as the starting point of postwar literary history. Situating the debate in tandem with three influential texts published at roughly the same time in the West—Lionel Trilling’s The Liberal Imagination (1951), Ruth Benedict’s The Chrysanthemum and the Sword (1946), and The God That Failed (1950), edited by Richard Crossman—the essay argues that the debate should be considered an early instance of the Cold War culture that would emerge globally in the decades that followed.

Introduction: The 1946-7 “Politics and Literature Debate” (Seiji to bungaku ronsō) among leftist Japanese writers and intellectuals is conventionally cited as the starting point for Japan’s postwar literary history. Reflecting on the disaster of the war and Japan’s imperialist aggression against its neighbors, as well as on the failure of the prewar proletarian culture movement to prevent that disaster, participants on both sides of the debate shared a strong commitment to the idea of Literature as a cornerstone to modern culture, as well as to the democratization of Japan and the rooting out of fascist and “feudal” elements from its political life. The source of their disagreement arose from sharply differing views of the correct relationship between those two goals: was literature properly autonomous from the political, or was it part and parcel of the political?

In some ways, the debate represented a resumption of disputes that had dogged the proletarian literature movement of the 1920s and 30s and that had been forced into silence by the fascist state’s censorship and repression of the left. But the debate also reflected something of a generational divide within the Japanese left, as a rising generation of critics such as Hirano Ken and Ara Masahito—many of them associated with the new cultural journal Kindai Bungaku (Modern Literature)—challenged the authority of more-established writers and critics such as Nakano Shigeharu and Kurahara Korehito, many of them veterans of the prewar proletarian literature, who were affiliated with the newly legalized Japan Communist Party and the journal Shin Nihon Bungaku (New Japanese Literature). As it unfolded across the pages of multiple journals and newspapers, the debate eventually involved dozens of writers. The debate ultimately died out without ever reaching a clear resolution, as other issues took center stage in intellectual life, notably the American Occupation’s Reverse Course and the resumption of intensified censorship against the JCP and other leftists under intensified Cold War conditions. But the after-currents of the debate would continue to shape Japanese literary criticism and intellectual life for decades to come.

Like much of Japan’s leftist and Marxist literary history, the Politics and Literature Debate was long ignored or glossed over in English-language studies of Japanese literary history. A research project organized in recent years by faculty and graduate students from Princeton University, Waseda University, and the University of Chicago aimed to rectify this situation by providing the first extensive English-language investigation into the debate. The project resulted in the publication of two volumes: The Politics and Literature Debate in Postwar Japanese Criticism, 1945-1952 (edited by Atsuko Ueda, Michael K. Bourdaghs, Richi Sakakibara, and Hirokazu Toeda; Lexington Books, 2017), an anthology of annotated translations of twenty-four key essays that constituted the original “Politics and Literature Debate,” and Literature among the Ruins, 1945-1955: Postwar Japanese Literary Criticism (same editors; Lexington Books, 2018), a collection of new scholarly essays on the debate by scholars from across North America and Japan. The following essay is taken from the latter volume and reprinted here (with some revisions) by kind permission of Lexington Books.

Early Freeze Warning: The Politics and Literature Debate as Cold War Culture

The Politics and Literature Debate of 1946–47 has long been taken as the starting point for postwar Japanese literary history. My purpose here, however, is to rethink it as an early skirmish in Cold War cultural politics. Instead of positioning the complicated disputes involving Hirano Ken, Nakano Shigeharu, and others in reference to the just-ended war of 1931–45, what happens when we map them in relation to the global Cold War that was just getting under way?

This is not an entirely new gesture. In rethinking Japan’s postwar culture through the lens of the Cold War, I follow in the wake of many others.1 Taking up the 1946–47 debates as early Cold War culture helps reveal connections with subsequent developments in hihyō (criticism) in the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s—that is, during the latter stages of the Cold War. More important, this rethinking productively shifts the ground from which an American scholar approaches Japan. Whereas the postwar Japan studies approach has often proceeded from the implicit (and sometimes explicit) assumption of America as the benefactor that rescued Japan from fascism, a Cold War framework situates the United States in a less-comfortable position, one in which its own stance as a perpetrator of geopolitical violence has to be raised alongside the study of Japanese cultural production. I conclude my essay with a consideration of American Japan studies as yet another instance of Cold War culture.

The rethinking I want to pursue requires transcending the boundaries of Japan to place the 1946–47 debates in a more global context. In the wake of the horrors of World War II, intellectuals around the world engaged in lively debates over the meanings and interrelationships of such concepts as “literature,” “politics,” “subjectivity,” “culture,” “nation,” “Marxism,” and “humanism.” We need only to think of such classic works as Auerbach’s Mimesis (1946), Wellek and Warren’s Theory of Literature (1946), Adorno and Horkheimer’s Dialectic of Enlightenment (1947), or Sartre’s What Is Literature? (1947) to sense this context.2 We might add Orwell’s Animal Farm (1945) to this list—and note that Occupation authorities arranged the 1949 publication of a Japanese translation of the novel and sponsored performances of a kamishibai storyteller adaptation aimed at factory workers, government officials, and labor unions.3 Of course, the Politics and Literature Debate unfolded within its own specific historical situation, yet its participants were aware that their activities as critics paralleled similar developments around the world.

The Politics and Literature Debate began with the April 1946 publication in the journal Ningen (Humanity) of a roundtable discussion on “The War Responsibility of Writers” (Bungakusha no sekimu). Skimming the table of contents of that journal from 1946 to 1947, we come across the following article titles:

Fukuro Ippei, “Saikin no soveto bungaku o megutte” (On recent Soviet literature) (January 1946)

Satō Saku, “Furansu bundan no shinchōryū” (Recent currents in French literary circles) (May 1946)

Honda Kiyoji, “Amerikateki shii” (American-style thought) (June 1946)

Takeda Taijun, “Chūgoku no sakkatachi” (China’s writers) (June 1946)

Ramon Fernandez, “Thought and Revolution” (July 1946)

Thomas Mann, Voyage with Don Quixote (serialized October–December 1946)

André Gide, “André Malraux (The Human Adventure)” (November 1946)

André Gide, “French-Style Dialogue” (January 1947)

Takahashi Yoshitaka, “Hesse mondai” (The Hesse problem) (February 1947)

André Malraux, Man’s Hope (March 1947)

In February 1946, Ningen also published a special issue devoted to “American Thought,” while in 1947 it ran a two-part special issue (July and September) on contemporary French literary trends. In April 1949 it carried Nakahashi Kazuo’s piece on “The Problem of Literature and Politics in Contemporary English Literature” (Gendai Eibungaku ni okeru bungaku to seiji no mondai), while in January 1952 it published Katō Shūichi’s translation of Sartre’s What Is Literature? Clearly, readers of the Politics and Literature Debate as it unfolded across the pages of Ningen and kindred journals in late-1940s Japan had access to timely information about similar debates underway around the globe.

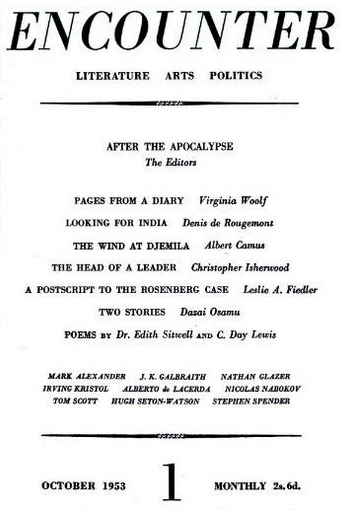

Moreover, intellectuals outside Japan, particularly after the Chinese Revolution (1949) and the outbreak of the Korean War (1950), showed keen interest in how Japanese intellectuals understood the relationship between politics and literature.4 As I discuss in the following, the monthly Encounter regularly included translations from modern Japanese literature as well as reportage on the intellectual milieu of 1950s Japan. Moreover, if we browse such American intellectual journals as Partisan Review or Commentary from this period, we find a striking resemblance to Ningen and its peers in Japan. During the early Cold War, in both Japan and the West a shared canon was emerging—centered on such figures as Sartre, Dostoyevsky, Mann, and Gide—as the ground for ongoing debates over the proper relationship between literature and politics. Rereading the 1946–47 Japanese debate in tandem with its counterparts abroad should open up a more global, dialogic understanding, as we come to see both what it shared with similar debates elsewhere and what was unique to it.

My initial tactic here for tackling this enormous problem is to reread the Japanese debate alongside three intertexts. These three works were published in the United States at roughly the time of the debate and played important roles in Cold War culture. Each remains in print today, and each was translated and debated within Japan. Directly or indirectly, the Japanese critics who engaged in the Politics and Literature Debate did so in dialogue with these texts, and through this dialogue concepts that would become fixtures of Cold War culture began to take shape. As Ann Sherif has reminded us, “culture during the Cold War reveals itself as the primary front or battlefield, the desired site of transformation and conviction.”5 Whether or not they were aware of it at the time, Japanese intellectuals in 1946–47 debating the proper meanings of “politics” and “literature” stood on the front lines of a battle for hearts and minds that would unfold across the globe in the coming decades.

I must note, though, that at the time of the Politics and Literature Debate, the term “Cold War” was not yet in wide circulation. George Orwell had used it or its cognates in several essays published in 1945–47,6 but the term did not win wide usage in English until around 1947; many point to the publication of Walter Lippman’s The Cold War that year as a turning point. The Japanese counterpart (reisen) seems to have entered the popular vocabulary around 1949. A keyword search through the online archive of the Asahi newspaper, for example, turns up an article of March 27, 1949, on East-West tensions (“Takaku kyōtei ni shippai: Uzumaku ‘tsumetai tatakai’ ” [Failure to reach multilateral accord: A spiraling “cold war”]) as the earliest usage of the kindred phrase tsumetai tatakai. Searches of other online databases of magazine articles also show the phrase reisen beginning to appear in 1949.

In other words, the writers who engaged in the 1946–47 debate could not have known at the time that they were early Cold Warriors. Nonetheless, I argue here that the positions and concepts they advanced contributed to the formation of what would become a global Cold War culture.

*

The first of the three intertexts is Lionel Trilling’s The Liberal Imagination. Trilling, a professor of English literature and comparative literature at Columbia University, was a leading figure among the group known popularly as the New York Intellectuals, centered on the anti-Stalinist Partisan Review. The Liberal Imagination first appeared in 1950, but Trilling had published many of its essays previously in literary journals, precisely during the period of the Japanese Politics and Literature Debate. The book became a best seller and a popular sensation.7 It would have a decisive impact on 1950s American literary criticism: one critic described it as being akin to “Holy Writ.”8

Lionel Trilling (Source: Wikipedia)

Trilling’s impact on Japan seems less dramatic. His work was not widely introduced into Japan until after the end of the US Occupation (1952)—in other words, well after the Politics and Literature Debate had reached its inconclusive conclusion. As part of a campaign by the Congress for Cultural Freedom and other Cold War cultural institutions to present his work to readers outside the United States, a partial Japanese translation of Liberal Imagination appeared in 1959 under a revised title: Literature and Psychoanalysis.9 The previous year saw the publication of a translation of The Middle of the Journey, Trilling’s 1947 autobiographical novel depicting his own break with communism (what would be termed in Japanese literary history a tenkō shōsetsu, a conversion novel).10 Prior to this, Trilling’s thought was introduced to Japanese readers through various journal articles.11 But as of 1946–47, Trilling does not seem to have much of a presence in the minds of Japanese literary critics. For example, an article in the October 1950 issue of Ningen surveys the ongoing reevaluation of Henry James in American literary history without mentioning Trilling, despite the important role he played in that reevaluation.12

The Liberal Imagination represents a bold rewriting of American literary history (and, to a lesser extent, world literary history) from an anti-Communist perspective. As such, it became a classic text of 1950s American “Cold War liberalism.”13 The “liberalism” that Trilling analyzes remains somewhat amorphous, but this does not prevent him from vowing in the work’s preface that “in the United States at this time liberalism is not only the dominant but even the sole intellectual tradition.”14 As Trilling openly acknowledges, his literary criticism is driven by a political agenda: he wants to define the proper relationship between politics and literature. Whereas what Trilling calls the liberal imagination in American cultural life holds that mankind is perfectible, literature’s duty is to resist this optimistic belief. While Trilling does not use the same language as Ara Masahito employed in such Politics and Literature Debate essays as “Dai-ni no seishun” (Second youth, 1946), it is clear he has something similar in mind: for Trilling, literature is properly a kind of negativity.

Lionel Trilling, The Liberal Imagination (1950)

Trilling in defining his mission presumes what he calls “the inevitable intimate, if not always obvious, connection between literature and politics” (xviii). Echoing Hirano Ken’s assertion that the defining keyword of Japanese literature in the Shōwa era has been “politics,” Trilling writes that “the literature of the modern period, of the last century and a half, has been characteristically political” (xviii), with Trilling defining that last term in “the wide sense of the word” (xvii) to include “the politics of culture, the organization of human life toward some end or other, toward the modification of sentiments, which is to say the quality of human life” (xvii). Literature in particular served as a source of persistent resistance to liberalism’s rationalizing ideologies, as an insistence on the necessity of imagination and sentiment to any concept of human freedom. In the face of liberalism’s tendency to simplify problems in order to organize solutions to them, literature acquired a force of political resistance by being “the human activity that takes the fullest and most precise account of variousness, possibility, complexity, and difficulty” (xxi).

Trilling is in particular fascinated by the relationship between literature and power. As in the Japanese Politics and Literature Debate, for Trilling this relationship could be understood in particular through an examination of the impact of the Communist Party on American letters. This thematic is developed in a chapter that was originally published in 1946 to commemorate the tenth anniversary of the Partisan Review—and one of the chapters omitted from the 1959 Japanese translation. This little magazine, Trilling notes, was at its inauguration in the early 1930s associated with the American Communist Party but quickly moved away from that position to become a new intellectual and literary voice for the non-Communist Party left.

The essay begins with a meditation on the waning power of literature. “It is now more than twenty years since a literary movement in this country has had what I have called power” (96). Trilling goes on to describe favorably the liberal worldview he believes is common to the educated classes in 1946 America, but he insists that it does not produce great literature. “Our liberal ideology has produced a large literature of social and political protest, but not, for several decades, a single writer who commands our real literary admiration” (98). It produces literature that is “earnest, sincere, solemn,” “a literature of piety” that “has neither imagination nor mind.” Trilling then lists what he takes to be the great writers of the twentieth century—Proust, Joyce, Lawrence, Eliot, Yeats—and argues that none respected the tenets of the liberal ideology. He concludes “that there is no connection between the political ideas of our educated class and the deep places of the imagination” (99).

In this environment, Trilling insists, the most necessary task is “to organize a new union between our political ideas and our imagination.” This explicitly involves rejecting the sway of the Communist Party:

The cultural program of the Communist Party in this country has, more than any other single intellectual factor, given the license to that divorce between politics and the imagination of which I have spoken. Basing itself on a great act of mind and on a great faith in mind, it has succeeded in rationalizing intellectual limitation and has, in twenty years, produced not a single work of distinction or even of high respectability. (100)

It is the fate of those who care about literature to remain political, he concludes, a hard fate of which “the only possibility of enduring it is to force into our definition of politics every human activity and every subtlety of every human activity” (100). The struggle to reunite the political with the imagination is ultimately, Trilling argues, a question of power. “The question of power has not always preoccupied literature. And ideally it is not the question which should first come to mind in thinking about literature. Quality is the first, and perhaps should be the only, consideration.” But because the very survival of “a particular quality” is at stake, “the question of power is forced upon us” (101). In such a moment, literature’s quality must be defended, and even if the writer of literature serves only his own muse, “the democracy that does not know that the daemon and the subject must be served is not, in any ideal sense of the word, a democracy at all” (102).

I’ve already suggested points of similarity between Trilling’s arguments and those offered by participants in the Politics and Literature Debate in Japan. In particular, Trilling shares many positions with Hirano Ken. Both share a seemingly unlimited faith in “literature” and its possibilities. Both likewise reject the notion that the “political” should enjoy primacy over the “literary,” and for that reason both men cast a suspicious gaze at literature written under the influence of communism. Trilling shares Hirano’s insistence on distinguishing literature from the political, yet he also openly acknowledges that his own literary criticism is operating (reluctantly, but necessarily) in the domain of politics. By contrast, as Victor Koschmann has noted, “Hirano’s extremely political essays about literary works contradicted his professed belief in the insularity of ‘literature’ from ‘politics.’”15 For Hirano, “politics” meant primarily the hegemony of the Japan Communist Party (JCP). As a result of this narrow definition, Hirano remains blind to the politicality of his own writings.

The two critics also position themselves differently in relation to the prewar proletarian literature movement. Trilling essentially quarantines proletarian literature from the canon of liberal imagination: his book is very much concerned with explaining why, for example, Henry James belongs but Theodore Dreiser (who, Trilling notes, joined the Communist Party late in his life) does not. Upton Sinclair, Jack London, John Steinbeck, and other radical writers largely disappear from Trilling’s version of American literary history. As Christina Klein has argued, Trilling and the other New York Intellectuals were motivated above all by the perceived need “to protect the realm of culture from corruption by insisting on a clear separation between art and politics. They tended to view forms of culture that retained any explicit social or political content as veering dangerously toward Stalinism.” This led to a tendency to celebrate modernist, difficult art that tended toward abstraction and formal experimentation over populist works that relied on sentiment and realism.16

|

Hirano Ken in 1943 (Source: Hathi Trust Library online version of Hirano Ken Zenshū, Vol. 1) |

Hirano employs a different strategy. Rather than isolate works of Japanese proletarian literature, Hirano embraces them. But his mode of embrace is revisionist: he rewrites the historical narrative of the proletarian literature movement, providing it with new beginning and ending points, a switch that has the effect of redefining the whole character of the movement. In “‘Seiji no yūisei’ to wa nani ka” (What is “the primacy of politics?,” September 1946), Hirano tries to justify his controversial equation of Kobayashi Takiji with Hino Ashihei by composing a revisionist history of the Japanese proletarian literature movement.17 This new version situates Hirano rather than the JCP as the proper heir to the prewar proletarian literature movement.

Hirano’s new narrative of that movement begins with Arishima Takeo’s “Sengen hitotsu” (One declaration, 1922).18 Arishima, a bourgeois novelist, wrote in response to Marxist critic Hirabayashi Hatsunosuke’s claim that literature was ultimately class based and that writers were unable to transcend their class origins. Arishima accepts Hirabayashi’s assertion, acknowledging that any attempt he as a bourgeois novelist made to speak for the proletariat would amount to arrogant self-deception. According to Hirano, Arishima was the first to broach “subjectively….the intelligentsia’s defeat” (116). In Hirano’s view, Arishima posed a fundamental challenge to proletarian literature, one that subsequent critics in the movement failed to confront. As a result of this original sin, the movement was characterized by an inability to define the proper relationship between the proletariat and literature, itself a product of bourgeoisie culture. Arishima’s fundamental challenge was forgotten, and what emerged ironically was a proletarian literature movement dominated by petit bourgeois intellectuals.

The new endpoint Hirano assigns to his revisionist history of proletarian literature is located in the works of yet another bourgeois author, Shiga Naoya. Shiga’s three letters to Kobayashi Takiji, published after the latter’s death from a brutal police beating, resurrect the contradiction that the proletarian literature movement was unable to resolve: that literature was originally a bourgeois cultural form, one that required a measure of autonomy to exist. In particular, Hirano focuses on a phrase that Shiga used to criticize Kobayashi’s writings: those works were “master-serving literature” (shujin-mochi no bungaku) (116). Hirano concludes that the proletarian literature movement’s inability to address the criticisms of Arishima and Shiga spelled its inevitable doom, that it would have failed even absent the external state pressures that were conventionally narrated as causing its downfall.

With his new beginning and conclusion in place, Hirano turns his attention to the meaning of the prewar proletarian literature movement for 1946 Japan. Here, it becomes clear that the direct target of Hirano’s revisionist history is Nakano Shigeharu. He notes that when Nakano discusses the relationship between the “democratic literary movement” of 1946 and earlier leftist culture, Nakano writes of the “so-called [iwayuru] proletarian literature movement” (119). Nakano does this, according to Hirano, because that earlier movement actually consisted of an alliance between working-class and petit bourgeois writers, with the latter being numerically dominant. Hence Nakano says it should properly have been called the revolutionary literature movement or the revolutionary petit bourgeois literature movement, but state repression prevented the use of the word “revolutionary.” Both the prewar and postwar movements aimed at a bourgeois democratic revolution, and as a result, according to Nakano, the 1946 democratic literature movement is the true heir to the proletarian literature movement.

Hirano rejects this historical narrative as dishonest. He notes that the prewar proletarian literature movement defined itself in large measure by its fierce opposition to bourgeois literature. He quotes from Nakano’s response to Nakamura Mitsuo’s 1935 critique of Nakano’s tenkō story “Dai-isshō” (Chapter 1, 1935), in which Nakano clearly identified bourgeois literature as the enemy of proletarian literature and attacked Nakamura as a mouthpiece for capitalist ideology. Hirano chides Nakano for adopting in 1946 the very position he had a decade earlier denounced as being the voice of capitalism. He accuses Nakano of distorting the history of the proletarian literature movement, of effacing the way it was in essence a movement that aimed to overthrow bourgeois culture, including bourgeois literature:

It is a plain fact that proletarian literature aspired above all to the liberation of the proletariat and wished to achieve a proletarian dictatorship. That is why proletarian literature from the beginning tried to align itself with the ‘directed consciousness’ called ‘world reform.’ While crying out for the overthrow of bourgeois literature, it could not but call itself proletarian literature. (121)

To claim now, as Nakano does, that this was merely a “so-called” proletarian literature movement or that it was from the start a democratic revolutionary movement that welcomed bourgeois writers is, Hirano insists, to distort historical reality. So long as Nakano refuses to fundamentally question the reasons for the rise of the mistaken doctrine of the “primacy of the political,” Hirano maintains, he will be unable to achieve an effective self-criticism that would establish the proper relationship between politics and literature. He will only lead postwar literature into a repetition of the failure of the proletarian literature movement.

What is needed in 1946, Hirano argues, is a clear understanding of the history of the proletarian literature movement. The insistence on the primacy of the political has to be reexamined as a misguided form of idealism, and the reasons for its appearance have to be understood. Hirano positions himself and his cohort as the ones who must undertake this rethinking of history. He proposes revisiting the works of largely forgotten proletarian movement writers such as Ikue Kenji and Tezuka Hidetaka to retrace the past of idealism that ultimately led to the notion of the primacy of the political. Clearly, Hirano places himself and like-minded writers as the true heirs to the proletarian literature movement, and a major purpose of the Politics and Literature Debate was to challenge the authority that Nakano and others in the JCP were claiming as the present-day heirs to that movement. To borrow from Satō Izumi’s reading of the debate, Hirano charges Nakano and the JCP with misrepresenting the past; he does so in order to undermine their claims to represent the subject of the democratic revolution in 1946.19

In sum, both Trilling and Hirano attempt to formulate an anti-Communist, left-of-center position for literature. For each, this involves defining an autonomous space for literature, a holy ground from which it could comment on the political without being absorbed into it. Trilling’s strategy for achieving this was to expel proletarian literature from the canon of American literature. Hirano, by contrast, penned a revisionist history of the movement that allowed him to lay claim to its legacy, positioning himself as its legitimate heir in 1946. As I show in the following, this reflects the very different statuses of Marxism and its political advocates in early Cold War Japan and the United States.

*

My second intertext is Ruth Benedict’s The Chrysanthemum and the Sword: Patterns of Japanese Culture (1946). Like Trilling, Benedict was a faculty member at Columbia University, and her reputation as a leading anthropologist was already well established before the war.20 Benedict launched her study of Japan in 1944 at the behest of the Office of War Information as a wartime intelligence project, but by the time she published the book in 1946, it served as a kind of guide for how to occupy Japan. The book was widely and positively reviewed in American scholarly journals, though some commentators quibbled with Benedict’s methodology and her interpretation of Japanese culture.

Ruth Benedict, The Chrysanthemum and the Sword (1946)

The book also attracted wide interest among intellectuals in Occupied Japan. A Japanese translation by Hasegawa Matsuji, a professor of linguistics at Tōhoku University, appeared in 1948 and became a hot topic, with such media as the front-page “Tensei jingo” (Vox populi, vox Dei) column in the Asahi newspaper introducing it to a wide readership.21 It also set off a debate among Japanese intellectuals, generating rebuttals by such prominent figures as sociologist Tsurumi Kazuko, philosopher Watsuji Tetsurō, and folklorist Yanagita Kunio.22 These Japanese debates were in turn reported back in the United States.23

When Benedict was writing Chrysanthemum and the Sword, the term “Cold War” did not exist. Nonetheless, she clearly grasped the idea. Near the book’s conclusion, Benedict speculates on possible outcomes for Japan’s postwar future, expressing concerns about the effect the global environment would have on the prospects for remaking Japan into a peaceful nation: The Japanese “hope to buy back their passage to a respected place among peaceful nations. It will have to be a peaceful world. If Russia and the United States spend the coming years in arming for attack, Japan will use her know-how to fight in that war.”24 In other words, Benedict saw Japan’s future as contingent on geopolitical relations between the United States and the Soviet Union. At least one early American reviewer of Benedict’s books explicitly shared this outlook.25

Keeping this in mind, it seems hardly coincidental that Benedict would labor to situate postwar Japan on the side of the capitalist liberal democracies. She repeatedly asserts that Japanese culture lacks the capacity to generate a “revolution.” Echoing E. H. Norman and Japanese Marxist historians, she denies that the Meiji Restoration constituted a bourgeois revolution. “There was no French Revolution” (72–73), or again, “But Japan is not the Occident. She did not use that last strength of Occidental nations: revolution” (132). Because of their social system, Japanese “can stage revolts against exploitation and injustice without even becoming revolutionists” (302). Those in the West who, looking to postwar Japan, “prophesied the triumph of radical policies at the polls have gravely misunderstood the situation” (302). She predicts Japan will follow a democratic course, albeit one distinct from the way the term “democracy” is understood in the United States. According to Benedict, postwar Japan may reform itself in a democratic direction, but it could not be the site of revolution.

To consider Benedict’s work in relation to Cold War thought, we must first explore the concept of “culture” that is central to her work. The Japanese culture she depicts is characterized by a complex “pattern”: it includes two contradictory tendencies, expressed by the keywords that form her title. Benedict begins her account by describing the contradictions that she believes mark Japanese culture. She declares that “the Japanese are, to the highest degree, both aggressive and unaggressive, both militaristic and aesthetic, both insolent and polite.” (2). Eventually, she pins this duality to child-rearing practices (286), and although she does not use this terminology, she describes a cultural identity that is suspended between a narcissistic imaginary stage (one she sees as grounded in the mirror stage, albeit in terms of Shinto religious practice [288–89]) and a more mature symbolic stage grounded in shame and fear of social ostracism. This split accounts for the contradictory impulses that she believes characterize Japanese culture. Benedict never cites Freud, but as with Trilling we see the influence of psychoanalytic thought in her work.

Japan’s fundamental tendencies may be contradictory, but in Benedict’s view they nonetheless form a coherent, “singular” cultural system (18). As critics have noted, Benedict’s version of Japanese culture is ahistorical and essentialist: it seems to have no connection to, for example, class conflict, capitalism, or Japan’s recent imperial past.26 Moreover, it is a culture utterly foreign to America, so that to understand it Americans have “to keep ourselves as far as possible from leaping to the easy conclusion that what we would do in a given situation was what they would do” (5). Benedict stresses the cultural difference of Japan. On (恩) and other Japanese keywords that can be translated as “obligation,” for example, escape an American’s grasp; “their specific meanings have no literal translation into English because the ideas they express are alien to us” (99). Yet such radical “difference” is to the social scientist “an asset rather than a liability” (10). She dismisses calls for a single, homogeneous global culture as a kind of “neurosis” (a keyword she shares with Trilling) and calls instead for “a world made safe for differences” (15).

Ruth Benedict in 1937 (Source: Wikipedia)

Benedict maintains that such difference is acceptable and desirable precisely because it is cultural—which is to say not biological. She stresses “the anthropologist’s premise that human behavior in any primitive tribe or in any nation in the forefront of civilizations is learned in daily living” (11). In such assertions, Benedict’s characteristically liberal stance emerges. The Chrysanthemum and the Sword is a continuation of Benedict’s lifelong project (shared with her mentor, Franz Boas) seen in such earlier works as Race: Science and Politics (1940) and her pamphlet The Races of Mankind (1943) aimed at denying race as a meaningful scholarly category. Benedict labors to replace anthropology’s earlier stress on race with a view that insists instead on the importance of culture, a project that took on added urgency in the wake of wartime genocide. Benedict’s efforts to deny scientific validity to a biological conception of race was noted by at least one early Japanese reader.27 In asserting the importance of cultural difference and rejecting racial prejudice, Benedict intends to provoke critical reflection not only among the Japanese but also among her American readers.28

In this, Benedict lays down the prototype for a key ideological tenet of what would become Cold War liberalism. In the ideological competition with the Soviet Union, the persistence of violent racism in the United States was an obvious Achilles’ heel. As a result, as Christina Klein has noted, the “Cold War consensus” that governed American culture after 1945 was defined not only by “containment”—that is, by what it was against (Communism)—but also by what it was for: “integration” and multiculturalism.

In contrast to nineteenth-century imperial powers, the captains of America’s postwar expansion explicitly denounced the idea of essential racial differences and hierarchies. They generated instead a wide-ranging discourse of racial tolerance and inclusion that served as the official ideology undergirding postwar expansion.29

In narrating a noncoercive mode for explicating American hegemony in Asia, cultural difference was now to be embraced, with cultural boundaries drawn only so that they could be crossed in the process of building the ties of a universal “family of man” based on sentiment, tolerance, and mutual respect.

As a result of this stress on integration, domestic American racism became a crisis for Cold War foreign relations. It was a troubling legacy of the sort of imperialism from which the United States was at pains to distinguish itself. Benedict was a pioneering champion of this line: she identifies the Asian Exclusion Act of 1924, for example, and “our racial attitudes toward the non-white peoples of the world” as one of the causal factors behind World War II (308–9).30 As Naoko Shibusawa has argued, however, Benedict’s reifying of Japanese cultural difference often “ended up reconstructing racism through other categories,” primarily culture.31 Replacing “race” with “culture” in this way draws a distinction that makes no real difference. In this, Benedict embodied one of the paradigmatic ambiguities of Cold War liberalism.

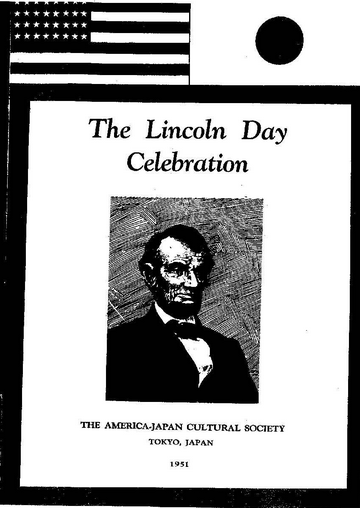

American Cold War ideologues struggled with the propaganda nightmare of domestic racism. In Occupied Japan, this resulted in, among other things, a deliberate foregrounding of the Great Emancipator, Abraham Lincoln, as a symbol of American democracy. Annual Lincoln Day celebrations were sponsored by the America-Japan Cultural Society with the backing of Occupation authorities.32 In a celebratory message read at the 1951 ceremony, Illinois governor Adlai Stevenson declared Lincoln a “world statesman” whose “concept of freedom and brotherhood recognized no barriers of geography, race or nationality” and concluded that “in these days of anxiety concerning the peace of the world we do well to look at his example of firmness and faith that liberty and justice will prevail over tyranny.” Another congratulatory message, from David Sarnoff, chairman of the board of RCA, likewise stressed Lincoln’s ideals as a tool to “dissolve prejudiced opinion.”33 The organizer of the event, Jiuji Kasai, repeated this emphasis on Lincoln as a symbol of integration and drew the connection to the contemporary politics of containment.

Since the Allied Occupation, the new Constitution was drafted and the democratic form of government was established in Japan. But, the bulk of our people do not yet understand the true meaning of democracy, as the Communists have been making sinister propaganda to confuse liberty with license. While the party politicians have been fighting for their own gain, the Soviet-directed Communists have organized their nation-wide cell systems with enormous funds. They are doing their utmost to destroy our old heritage as reactionary, and are attacking American democracy as capitalistic imperialism in order to create anti-American feeling among the Japanese people . . . Against their relentless attack, the abstract theories of democracy had no positive and concrete force. At this moment, the life and character of Abraham Lincoln came to me in bold relief to illustrate to the Japanese people America’s true spirit of democracy in contrast with Soviet Communism. (11–12)

Program, 1951 Lincoln Day Celebration in Tokyo

Returning to Benedict, in addition to her linkage of antiracism to anti-Communism, I’d like to zero in on another site of overlap with the Politics and Literature Debate: her use of two keywords, “culture” and “literature.” Benedict is seeking, as her subtitle tells us, “patterns in Japanese culture.” “Culture” here refers not to elite aesthetic products, such as novels or poems, but rather “the commonplace” (11) or what has become unconscious “habit” through repetition in childhood (281). Yet as an anthropologist studying an enemy culture during wartime, Benedict lacked direct access to daily life in Japan. In place of conventional fieldwork, she relied on interviews with Japanese-Americans, previously published secondary sources on Japan, and—of most interest for our purposes—Japanese literary works. (Benedict, in fact, began her scholarly career as a specialist not in anthropology but in literature.)34 For example, her explication of the untranslatable on from Japanese culture is grounded in a reading of Natsume Sōseki’s 1906 novel Botchan (107–9). Likewise, she cites literary texts as sources to demonstrate that romantic love is widespread in Japan (183), that the flesh and spirit are not at war in Japanese culture (189–90), and that Japanese moral expectations for justice differ from those of Westerners (198–207). Benedict even alludes to Kobayashi Takiji and Japan’s proletarian literature movement.35

For Benedict, literature does not function as an exceptional product grounded in the talent of individual genius but rather represents Japanese culture as a whole in its everyday habits and practices. Literature for her is inherently national literature. Here, she adopts a position contrary to that of Hirano Ken or Ara Masahito (or, for that matter, Lionel Trilling), for whom literature is a rarified product of unique authors and their existential encounters with radical negativity; it is national only in the sense that Japan in their view had failed to produce a figure on a par with Romain Rolland or Thomas Mann. The crisis Hirano and Ara confront is Japan’s failure, due to its critical inability to distinguish politics from literature, to produce a true literature. Such a literature would not be representative of the Japanese nation but rather exceptional to it.

Ironically, the liberal Benedict’s position here is closer to that of Communist Nakano Shigeharu. In “Bungakusha no kokumin toshite no tachiba” (The role of the writer as national citizen, February 1946), Nakano vows, “Japanese literature is the literature of the Japanese people. It is born in Japan; it finds its life first among the Japanese people. In the absence of Japan and the Japanese people, Japanese literature itself would not exist. The fate of Japan, and that of the Japanese people, is itself the soil in which Japanese literature is rooted.”36 Nakano would subsequently condemn Hirano and Asa for mounting what he called the literary reaction, bemoaning their advocacy of what he sees as an elitist notion of freedom.37 According to Nakano, in the democratic revolution of postwar Japan, reactionary forces mobilize literature and other forms of culture as their primary tools, because contemporary literature manifests the spiritual weakness of the people (minzoku) that is a result of the recent war.38 He stresses that the postwar democratic revolution must be grounded not in exceptional individuals but rather in communal effort.

This means the participation of the investigators, the investigated, and the readers, all together, in the task of establishing the civic self-consciousness of the Japanese literati. The purpose of this is not to have a rare, fortuitous, and absolutely flawless conscience; rather, it is for ordinary writers in general to work together in paving a new road toward the achievement of civic self-consciousness. Here, too, artistic and theoretical literary creations form a broad foundation.39

Writers can at best serve as “teachers,” pointing out the proper course that the national people should follow in their daily lives.40

A few years later Takeuchi Yoshimi would develop a similar line of thought. In the national literature debate of the early 1950s, in many ways a continuation of the Politics and Literature Debate, Takeuchi explicitly rejected the widespread view of “the writer as an isolated individual, alone with his thoughts, which require unique artistic expression” and who must “pursue his craft alone, where he can all the more easily be true to himself and his individual genius.”41 For Takeuchi, the crucial question to explore about Japanese literature as national literature was, “Why didn’t Japan produce anyone like Lu Xun?”42 For Takeuchi, Lu Xun represented a genuinely national writer whose works embodied the collective revolutionary national project of China. By contrast, Japan’s proletarian literature movement represented the failure of Japanese cultural modernity as a whole: it was a characteristic instance of an external authority being reproduced slavishly by a slave that refused to recognize its own status as slave. Moreover, he insisted, postwar critics on both sides of the Politics and Literature Debate continued to miss the point.

From the perspective of Chinese literature, it is self-evident that writers act as the agents or spokesmen of national feeling. And it is on the basis of such national feeling that writers are judged, i.e., how and to what extent this feeling is represented. With Japanese literature, however, things are entirely different. The question of whether a writer represents national feeling is completely separated from the question of how this feeling is actually expressed, such that an additional operation is required in order to link the two together. Here lies the ground upon which the typical Japanese question of “politics and literature” is posed. Japanese critics see this separation as of a piece with the radical split in consciousness inherent in modern literature as such, but I would disagree. Rather I would concur with [Chinese poet] Li Shou that it must be seen as symptomatic of the feudal nature of Japanese literature. In this respect, the journal New Japanese Literature [Shin Nihon bungaku] hardly represents an exception.43

Both Japan’s proletarian literature movement and the postwar critics fighting over its legacies ultimately became instances of the decadence and factionalism that Takeuchi saw as representative of Japanese culture in its incomplete modernity.

Takeuchi Yoshimi in 1953 (Source: Wikipedia)

Nakano and Takeuchi parallel Benedict in the way they take literature as representative of Japanese national culture in its everyday habits and practices. But there is an obvious difference between them as well. For Benedict, literature is national but not political: Japanese literature reflects a national culture that is impervious to revolution, even in the turbulent postwar era. Labor activism in postwar Japan was like premodern peasant revolts, she argues, explaining that they were “not class warfare in the Western sense, and they were not an attempt to change the system itself” (310). In contrast, for both Nakano and Takeuchi, because Japanese literature is inherently a national literature, it must also be political: it must become a crucial tool in a national awakening that will complete the revolution to realize modernity in Asia. This difference in positions would continue to reverberate throughout the Cold War as both a political and literary question.

*

The third American intertext is the collection The God That Failed, published in 1950. Edited by the British Labour MP Richard Crossman, it consists of six autobiographical essays by prominent writers, each depicting his own youthful involvement and subsequent disillusionment with the Communist Party. In other words, it is an anthology of what Japanese literary scholars would call tenkō literature. Its roster of contributors constitutes a stellar collection of midcentury Western literati: novelists Arthur Koestler, Ignazio Silone, Richard Wright, and André Gide (recipient in 1947 of the Nobel Prize in Literature); journalist Louis Fischer; and poet Stephen Spender. The book created a sensation upon publication, with the English-language version selling more than 160,000 copies within four years.

Not specifically an American product—among the authors only Wright and Fischer were US citizens—nonetheless the work became a cultural Bible of the American-centered anti-Communist bloc that emerged during the Cold War. The book’s wide promulgation abroad was due in large measure to direct and indirect CIA sponsorship, the CIA having bankrolled the Congress for Cultural Freedom (CCF), the organization responsible for the book’s publication. With this support, The God That Failed was quickly translated into sixteen languages.44

A Japanese edition translated by Murakami Yoshio and Yarita Ken’ichi appeared under the title Kami wa tsumazuku in 1950. The book attracted considerable attention in Japan. It was reviewed in the Asahi newspaper, and Takeuchi Yoshimi published a positive review in Ningen. He raises questions about the contributors’ level of understanding of East Asia but finds in The God That Failed an opportunity to again criticize the Japanese literary world by negative comparison:

On reflection, I wonder who among Japanese literati can be said to have written this sort of confession. They know how to drown themselves in emotions and how to make sharp comebacks, but they never narrate their own experiences of failure for the sake of those around them, those who would come after (excepting only some fragments from Tanaka Hidemitsu and the unfinished confession of Takami Jun). They were simply playing at politics and were never authentic literati. Japan never had even a real tenkō literature.45

After publication of the Japanese translation of The God That Failed, its authors continued to appear before Japanese readers. Translations of essays on the problems of politics and literature by Spender, Silone, and Gide appeared in a number of Japanese intellectual journals around 1950. The CCF was particularly active in Japan, hosting international conferences in Tokyo in 1955 and 1960. Stephen Spender, the editor of its house organ, Encounter, would travel to Japan in 1957 and meet with a number of Japanese writers and critics.46 Arthur Koestler would follow in 1959.47

Kami wa Tsumazaku (1950) the Japanese edition of The God That Failed, trans. Murakami Yoshio and Yarita Ken’ichi |

The God That Failed includes numerous references to Asia and Japan—in particular to the attempts by Western Communist parties to develop policies toward fascist Japan during the war years. Moreover, it also provides much evidence of the antiracist position characteristic of Cold War liberalism. Containment cannot be achieved without integration and respect for cultural difference, the various writers realize. As Crossman notes in his introduction, Richard Wright’s flirtation with Communism “is a reminder that, whatever its failures in the West, Communism still comes as a liberating force among the Colored peoples who make up the great majority of mankind.”48 Wright himself acknowledges that it was Stalin’s advocacy of respect for minority cultures that attracted him to the Communist Party: “I had read with awe how the Communists had sent phonetic experts into the vast regions of Russia to listen to the stammering dialects of peoples oppressed for centuries by the czars . . . And I had exclaimed to myself how different this was from the way in which Negroes were sneered at in America” (130).

In particular, when we read The God That Failed as an intertext of the Politics and Literature Debate, one feature is highlighted: Japanese literary critics in 1946 were already relying on keywords and concepts that in coming years would become central to the thought of anti-Communist intellectuals around the globe. The Italian novelist Silone’s description of the act of writing literature, for example, echoes the existentialist language of struggle and individuality that had a few years earlier appeared in Hirano’s and Ara’s essays in Japan: “For me writing has not been, and never could be, except in a few favored moments of grace, a serene aesthetic enjoyment, but rather the painful and lonely continuation of a struggle” (81). Silone also relates the appeal of Communism to youth in language remarkably similar to that used by Ara in his essay “Dai-ni no seishun.”

Hirano’s explication of the problematic relationship of the bourgeois writer to proletarian literature likewise foreshadows language used by several God That Failed authors. Koestler writes sarcastically of the position of middle-class literati within the proletarian culture movement:

A member of the intelligentsia could never become a real proletarian, but his duty was to become as nearly one as he could. Some tried to achieve this by forsaking neckties, by wearing polo sweaters and black fingernails. This, however, was discouraged: it was imposture and snobbery. The correct way was never to write, say, and above all never to think, anything which could not be understood by the dustman. (49)

Wright comments on the tension he felt among supposed comrades who looked down on him for being a bourgeois intellectual, a label that shocked him given that he had only a primary education and was sweeping streets for a living at the time. Spender writes of the “creative artist” whose “sensibility, which is decided for him in his childhood, is bourgeois. He can scarcely hope to acquire by an act of political will a working-class mentality” (236).

The language that Hirano uses to define the difference between “politics” and “literature” would also be replicated in The God That Failed. According to Hirano, “the definitive characteristic of politics is that the end justifies the means.” By contrast, “In matters of literature and art, in particular, the very process of edging ever closer step-by-step toward the end is in itself the end. In their domain, not even the slightest separation of ‘means and end’ is permitted. In other words, it is from the means themselves that the end to be realized must be worked out.”49 Hirano condemns the JCP and proletarian activists for the ethical failing of believing the end (revolution) justifies whatever means are taken to achieve it. Literature for Hirano defines a humanistic ethical practice in which the means must be an end in itself. Nearly all The God That Failed authors similarly invoke the language of a Kantian categorical imperative: it clearly became a kind of cliché of anti-Communist writing. Koestler insists that “the end justifies the means only within very narrow limits” (68), while Fischer writes,

My pro-Sovietism led me into the further error of thinking that a system founded on the principle of “the end justifies the means” could ever create a better world or a better human being.

Immoral means produce immoral ends—and immoral persons—under Bolshevism and under capitalism. (225).

Likewise, Spender writes that to accept the Communist view meant that “one did not have to consider, except from the point of view of their effectiveness, the means which were used” (235).

In sum, bringing in The God That Failed as an intertext allows us to see how the Politics and Literature Debate participated in the creation of a vocabulary of clichés that would be shared by anti-Communist intellectuals around the globe. Reading the two sets of texts side by side also allows us to see differences in the contemporary situations of the United States and Japan. In the Anglophone world, The God That Failed provided a rare public platform for former Communists, normally the target of silencing under Red Scare censorship. Reading its various autobiographical narratives, we find—especially when compared with the more one-dimensional writings of other contemporary anti-Communist thinkers—that the representation of Communism presented by The God That Failed writers is diverse and complex. Moreover, their accounts of the injustices generated by contemporary Western racism, imperialism, and capitalism are often sharply critical.50 In other words, The God That Failed provided an opportunity for a leftist social critique that found few other mainstream outlets under prevailing political conditions in the United States. It seems that leftist writers who foregrounded their anti-Communist credentials were permitted a wide degree of latitude in criticizing liberal capitalist society. On the other hand, as the informal censorship imposed on novelist Pearl S. Buck and journalist Helen Mears in the late 1940s and 1950s indicates, intellectuals who criticized American foreign policy—that is, openly opposed US Cold War policies toward the Communist bloc—risked losing access to public forums for commenting on America’s domestic social problems.51

This suggests one important difference between the Politics and Literature Debate and The God That Failed. The authors who published in The God That Failed and similar venues in the United States did not have to engage in direct debates with actual Communists. Their opponents were largely excluded from mainstream literary and political publications and were thus denied effective public venues from which to answer the criticisms launched at them. This situation was decisively different from that in 1946–47 Japan. Hirano, Ara, and others who criticized the JCP from the standpoint of liberalism or humanism did so in a situation that required them to respond directly, and sometimes with obvious discomfit, to counterarguments launched against them by Nakano and other JCP intellectuals.

This difference was a by-product of what Marukawa Tetsushi and Ann Sherif have called the air-pocket situation that characterized Cold War Japan, buffered from the most drastic and violent manifestations of the global struggle that characterized the era. Unlike Germany, China, Korea, or Vietnam, postwar Japan was not partitioned into rigidly Communist and anti-Communist zones. And while Japan saw its share of Red purges, unlike the United States its Communist Party remained throughout the Cold War a viable political party. This air-pocket condition (perhaps most similar to that of France, Italy, and other undivided Western European countries) was one of the distinguishing conditions that shaped Japanese literary criticism in the period, and we see its impact on the Politics and Literature Debate as well. It does not mean, however, that Japan was somehow immune from the Cold War: this air-pocket situation was itself a product of the global Cold War.

*

In conclusion, as an extension of the preceding discussion, I’d like to touch on the history of Japanese studies, especially Japanese literary studies, in North America. Like postwar Japanese literary criticism, Japan studies in the American academy was a product of Cold War ideological struggle, specifically the promotion of area studies as a new academic field that could contribute to the projects of containment and integration. The founding figures of Japanese literary studies in the United States were by and large trained within the world of the three intertexts discussed in the preceding. Benedict’s The Chrysanthemum and the Sword was itself, of course, a foundational text of postwar Japan studies. Trilling influenced a number of early scholars of modern Japanese literature, including Donald Keene, who studied with him at Columbia.52 Edwin McClellan, another seminal scholar of Japanese literature, trained in the 1950s at the University of Chicago under the direction of Friedrich Hayek, a key figure in Cold War conservative anti-Communism.53 Edward Seidensticker, future translator of The Tale of Genji, was in the late 1950s and early 1960s employed as Japan liaison by the CCF, the organization behind The God That Failed. Seidensticker was based in Tokyo and reported to, among others, undercover CIA agent Scott Charles at the organization’s headquarters in Paris. During the course of his employment Seidensticker traveled on CCF business around the world, including visits to London, Paris, Basel, Cairo, Karachi, Bombay, New Delhi, Seoul, and Manila. In his autobiography, he indicates that he was aware at the time of the CCF’s CIA connections.54

I began this essay by listing articles from Ningen as a way of capturing a snapshot of Japanese literary critical discourse circa 1946–47. Let me conclude with a list of articles on Japan from another literary journal, Encounter, during the first five years of its existence:

Dazai Osamu, “Two Stories,” trans. Edward Seidensticker (no. 1, October 1953)

Melvin J. Lasky, “A Sentimental Traveller in Japan (I)” (no. 2, November 1953)

Melvin J. Lasky, “A Sentimental Traveller in Japan (II)” (no. 3, December 1953)

François Bondy, “ ‘Asia’: Does It Exist?” (no. 4, January 1954)

Edmund Blunden, “Eight Japanese Poems” (no. 5, February 1954) (translations of haiku by Bashō, Buson, and others)

William Barrett, “The Great Bow” (book review of Eugen Herrigel, Zen and the Art of Archery) (no. 7, April 1954)

J. Enright, “Notes from a Japanese University” (no. 8, May 1954)

Raymond Aron, “Asia: Between Malthus and Marx” (no. 11, August 1954)

Ken’ichi Yoshida, “The Literary Situation in Japan” (no. 18, March 1955)

John Morris, “Reflections in a Japanese Mirror” (film reviews of Seven Samurai and Children of Hiroshima) (no. 21, June 1955)

Christopher Sykes, “Hitler Leads to Hiroshima” (book review of Michihiko Hachiya, Hiroshima Diary) (no. 25, October 1955)

Hilary Corke, “Opening Up” (book review of Jun’ichirō Tanizaki, Some Prefer Nettles) (no. 31, April 1956)

Ibuse Masuji, “Crazy Iris,” trans. Ivan Morris (no. 32, May 1956)

Herbert Passin, “Letter from Tokyo: Headhunters, Watersprites, and Heroes” (no. 36, September 1956)

Mishima Yukio, “Hanjo,” trans. Donald Keene (no. 40, January 1957)

Herbert Passin, “A Nation of Readers” (no. 42, March 1957)

Angus Wilson, “A Century of Japanese Writing” (book review of Donald Keene, ed., Modern Japanese Literature) (no. 42, April 1957)

Herbert Passin, “The Mountain Hermitage: Pages from a Japanese Notebook” (no. 47, August 1957)

Dwight MacDonald, “Fictioneers” (book review of Yasunari Kawabata, Snow Country) (no. 48, September 1957)

Bertrand de Jouvenel, “Asia Is Not Russia: Or America Either” (no. 49, October 1957)

Edward Seidensticker, “The World’s Cities: Tokyo” (no. 50, November 1957)

Stephen Spender and Angus Wilson, “Some Japanese Observations” (no. 51, December 1957)

Nakashima Ton [Nakajima Atsushi], “The Expert,” trans. Ivan Morris (no. 56, May 1958)

Edward Seidensticker, “On Trying to Translate Japanese” (no. 59, August 1958)

J. Enright, “Empire of the English Tongue” (no. 63, December 1958)

The editorial staff of Encounter largely overlapped with the team that produced The God That Failed. A CCF publication secretly bankrolled by the CIA and British intelligence services, Encounter was aimed at a wide readership in Europe, Asia, South America, and Africa. Its propaganda targets were not Marxists or proponents of anti-Americanism but rather centrist or left-of-center intellectuals prone to advocate a stance of geopolitical neutralism—in Japan, those who would ally with the Japan Socialist Party and who might read, for example, Shiseidō’s monthly journal Jiyū, also bankrolled by the CCF.55

The journal’s editors knew that to be effective, they had to keep the journal free of the smell of obvious propaganda. When we page through issues of Encounter from the 1950s, we encounter the names of Trilling and several God That Failed authors. As the preceding list shows, we also encounter the names of the scholars who built the field of Japanese literary studies in North America: Keene, Seidensticker, and Ivan Morris. Some of the earliest translations of giants of modern Japanese literature first appeared in the journal, and it regularly reported on the current state of literary criticism and intellectual discourse in Japan.

|

The inaugural issue of Encounter (1953), featuring Edward Seidensticker’s translations of stories by Dazai Osamu |

For the first generation of scholars of Japanese literature in the United States during the 1950s, Encounter seems to have been an important venue. Through it, their early translations and criticism reached a broad audience of general readers. It is unclear how many of them (besides Seidensticker) knew of the journal’s ties to the CIA, or how they would have responded to such knowledge. But it does seem clear that the Cold War propaganda vehicle Encounter played an important role in establishing Japanese literary studies as a discipline and in presenting its scholarship to a global audience.

I conclude with this detour to remind us that not only postwar Japanese literary criticism but also the framework through which we in the English-speaking world study Japanese literature are rooted in the global Cold War. The Cold War is generally said to have ended around 1990 with the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the Soviet empire in Eastern Europe, although continuing tensions in East Asia (Korea, Taiwan, Okinawa, China) make the Cold War seem more like, to paraphrase William Faulkner (whose 1955 goodwill visit to Japan was another US Cold War propaganda effort), a past that isn’t even past yet. The Politics and Literature Debate can help us understand the position of Japanese literature in the Cold War—if we keep in mind that the lens through which we examine it is also a legacy of that ideological struggle.

Notes

See, for example, Marukawa Tetsushi, Reisen bunkaron: Wasurerareta aimai na sensō no genzaisei (On Cold War culture: The contemporariness of the forgotten enigmatic war) (Tokyo: Sōfūsha, 2005), and Ann Sherif, Japan’s Cold War: Media, Literature, and the Law (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009).

On Adorno, Horkheimer, and Auerbach as figures of Cold War culture, see Andrew Rubin, Archives of Authority: Empire, Culture, and the Cold War (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2012), 74–86, 90–108. On René Wellek and Austin Warren, see Mark Walhout, “The New Criticism and the Crisis of American Liberalism: The Poetics of the Cold War,” College English, 49, no. 8 (December 1987): 861–71.

Rubin, Archives of Authority, 39–43. On US Cold War cultural policy in Japan and Okinawa, see Chizuru Saeki, U.S. Cultural Propaganda in Cold War Japan: Promoting Democracy 1948–1960 (Lewiston, N.Y.: Mellen Press, 2007), and Michael Schaller, The American Occupation of Japan: The Origins of the Cold War in Asia (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985).

See, for example, Nora Waln, “Is Japanese Youth Going Communist?” Saturday Evening Post, August 6, 1949, 36–37, 76–78; Joseph Yamagiwa, “Fiction in Post-War Japan,” Far Eastern Quarterly 13, no. 1 (November 1953): 3–22; Harry Emerson Wildes, “The War for the Mind of Japan,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 294 (July 1954): 1–7; and Anthony West, “Letter from Tokyo,” New Yorker, June 22, 1957, 33–73.

See, for example, George Orwell, “The Future of Socialism IV: Toward European Unity,” Partisan Review, July–August 1947, 346–51.

Louis Menand, introduction” to The Liberal Imagination, by Lionel Trilling (New York: New York Review of Books, 2008), vii.

George Watson, “The Empire of Lionel Trilling,” Sewanee Review 115, no. 3 (2007): 484–90. The “Holy Writ” passage appears on 484.

Lionel Trilling, Bungaku to seishin bunseki, trans. Ōtake Masaru (Tokyo: Hyōronsha, 1959). On the efforts to transmit Trilling’s writings around the globe, see Rubin, Archives of Authority, 68–69.

Lionel Trilling, The Middle of the Journey, trans. Saitō Kazue and Ōtake Masaru as Tabiji no naka ni, in Gendai Amerika bungaku zenshū (Complete works of contemporary American literature), (Tokyo: Arechi shuppansha, 1958).

See, for example, Nishikawa Masami, “Lionel Trilling-cho, ‘The Liberal Imagination,’ Morton Dauwen Zabel-cho, ‘Literary Opinion in America’ ” (Lionel Trilling’s The Liberal Imagination, Morton Dauwen Zabel’s Literary Opinion in America), Eibungaku kenkyū 28, no. 2 (1952): 254–57; Ōtake Masaru, “Futatabi Toriringu ni tsuite” (Another consideration of Trilling), Tōkyō keidaigaku gakkai 12 (1954): 67–95; and Ōnuki Saburō, “Lionel Trilling no shōsetsuron” (On Lionel Trilling’s novels), Kenkyū ronshū: Shinshū daigaku kyōikugakubu jinbun shakai 3 (1953): 64–73. The last appears to be a Japanese translation of an essay by Trilling on fiction, but I have been unable to identify the original source.

Taniguchi Rikuo, “Amerika bunmei kara no tōsō: Henrī Jeimuzu ni kansuru oboegaki” (Struggle from American civilization: A note on Henry James), Ningen 5, no. 10 (October 1950): 16–29.

Russell J. Reising, “Lionel Trilling, The Liberal Imagination, and the Emergence of the Cultural Discourse of Anti-Stalinism,” boundary 2 20, no. 1 (1993): 94–124.

Trilling, The Liberal Imagination, xv. Subsequent references to this work are given parenthetically.

J. Victor Koschmann, Revolution and Subjectivity in Postwar Japan (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), 75.

Christina Klein, Cold War Orientalism: Asia in the Middlebrow Imagination, 1945–1961 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003), 66.

Kobayashi Takiji was the leading figure of the prewar proletarian movement and became a martyr-figure on the Japanese left after his murder by Japanese police in 1933. Hino Ashihei came to prominence in the 1930s as the author of pro-military propagandistic novels. See Hirano Ken, “What is the ‘Primacy of the Politics,” trans. Miyabi Goto and Ron Wilson, in The Politics and Literature Debate in Postwar Japanese Criticism 1945-52, ed. Atsuko Ueda, Michael K. Bourdaghs, Richi Sakakibara, and Hirokazu Toeda (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2017), 115-125. Subsequent references to this essay are given parenthetically. For the original Japanese, see Hirano Ken, “‘Seiji no yūisei’ to wa nani ka,” reprinted in Hirano Ken zenshū (Collected Works of Hirano Ken) (Tokyo: Shinchōsha, 1974-1975), 1:216–25.

On Arishima’s notion of “representation” in politics and literature and its reappropriation in the postwar debate, see Satō Izumi, Sengo hihyō no metahisutorī: Kindai o kioku suru ba (The metahistory of postwar criticism: Modern sites of memory) (Tokyo: Iwanami shoten, 2005), 165–87.

See, for example, Margaret Mead, “Ruth Fulton Benedict 1887–1948,” American Anthropologist, n.s., 51, no. 3 (July–September 1949): 457–68.

For “Tensei jingo” columns that touch on The Chrysanthemum and the Sword, see the Asahi newspapers of February 8, 1949, and May 4, 1950.

On the Japanese reception of Benedict’s work, see Sonia Ryang, “Chrysanthemum’s Strange Life: Ruth Benedict in Postwar Japan,” Occasional Paper 32 (July 2004), Japan Policy Research Institute, University of San Francisco Center for the Pacific Rim. See also Minzokugaku kenkyū 14, no. 4 (May 1950), for a special issue devoted to Benedict, including essays by Yanagita and Watsuji; Tsurumi Kazuko, “Kiku to katana: Amerikajin no mita Nihonteki dōtoku-kan” (The Chrysanthemum and the Sword: An American view on the Japanese sense of morality) Shisō 276 (March 1947): 221–24; and Tsuda Sōkichi, “Kiku to katana no kuni: Gaikokujin no Nihon kenkyū ni tsuite” (The land of the chrysanthemum and the sword: Regarding research on Japan by foreigners) Tenbō 65 (May 1951): 6–25.

John W. Bennett and Michio Nagai, “The Japanese Critique of the Methodology in Benedict’s ‘Chrysanthemum and the Sword,’ ” American Anthropologist, n.s., 55, no. 3 (August 1953), 404–11.

Ruth Benedict, The Chrysanthemum and the Sword: Patterns of Japanese Culture (1946; repr., New York: Meridian, 1974), 315. Subsequent references to this work are given parenthetically.

“What Mrs. Benedict has done by way of interpreting Japanese culture needs to be done by the same investigator, or by someone else equally competent, for the culture and life of the Russian people. In such interpretations lies the road to that world understanding which is needed in order that the United Nations may develop and become effective” (Emory S. Bogardus, review of The Chrysanthemum and the Sword, by Ruth Benedict, Social Forces 25, no. 4 [May 1947]: 454–55).

“The author situates the cultural anthropologist on the front lines of the race problem as a scientist who resolves the anxieties and discord that are entangled in this problem” (Hayashi Sanpei, “Kokuminsei hihan no ichi shiten: Rūsu Benedikuto-cho Kiku to katana” [From the perspective of critique of nationality: Ruth Benedict’s The Chrysanthemum and the Sword], Amerika kenkyū 5, no. 5 [May 1950]: 69–74).

See Richard Handler, “Boasian Anthropology and the Critique of American Culture,” American Quarterly 42, no. 2 (June 1990): 252–73, and Clifford Geertz, Works and Lives: The Anthropologist as Author (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1988), 102–28.

See Lisa Yoneyama, “Habits of Knowing Cultural Differences: Chrysanthemum and the Sword in the U.S. Liberal Multiculturalism,” Topoi 18, no. 1 (1999): 71–80.

Naoko Shibusawa, America’s Geisha Ally: Reimagining the Japanese Enemy (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2006), 296.

On the Lincoln Day celebration, see Saeki, U.S. Cultural Propaganda, 118–24. See also the commemorative pamphlet The Lincoln Day Celebration (Tokyo: America-Japan Cultural Society, 1951).

Stevenson’s and Sarnoff’s messages are reproduced in Lincoln Day Celebration, 5, 8. Subsequent quotations from this work will be cited parenthetically.

On Benedict’s literary past, see C. Douglas Lummis, “Ruth Benedict’s Obituary for Japanese Culture,” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus Volume 5, Issue 7 (July 19, 2007), accessed August 31, 2020.

“Japan also has her proletarian novels protesting desperate economic conditions in the cities and terrible happenings on commercial fishing boats,” but Benedict identifies these as being outside the mainstream of what she calls character novels, presumably referring to the I-novel genre (166).

Nakano Shigeharu, “The Role of the Writer as National Citizen,” trans. Scott W. Aalgaard and annotated by Richi Sakakibara and Mariko Takano, Politics and Literature Debate in Postwar Japanese Criticism, ed. Ueda et al., 159-69; this passage appears on 159. For the original Japanese, see Nakano Shigeharu, “Bungakusha no kokumin toshite no tachiba,” in Nakano Shigeharu zenshū (Complete Works of Nakano Shigeharu) (Tokyo: Chikuma shobō, 1979), 12:25.

Nakano Shigeharu, “The Humanity of Criticism I: Concerning Hirano Ken and Ara Masahito,” trans. Joshua Solomon and Kaori Shiono, Politics and Literature Debate in Postwar Japanese Criticism, ed. Ueda et al., 105-14. For the original Japanese, see Nakano Shigeharu, “Hihyō no ningensei I: Hirano Ken Ara Masahito ni tsuite,” in Nakano Shigeharu zenshū, 12:84.

Nakano Shigeharu, “The Humanity of Criticism II: On the Literary Reactions, et Cetera,” trans. Joshua Solomon and Kaori Shiono, Politics and Literature Debate in Postwar Japanese Criticism, ed. Ueda et al., 137-49. For the original Japanese, see Nakano Shigeharu, “Hihyō no ningensei II: Bungaku handō no mondai nado,” in Nakano Shigeharu zenshū, 12:96.

Nakano, “The Role of the Writer as National Citizen,” 166. For the original Japanese, see Nakano, “Bungakusha no kokumin toshite,” 32.

Richard F. Calichman, ed. and trans., Introduction to What Is Modernity? Writings of Takeuchi Yoshimi, by Takeuchi Yoshimi (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005), 3.

Takeuchi Yoshimi, “Ways of Introducing Culture (Japanese Literature and Chinese Literature II)—Focusing Upon Lu Xun,” trans. Richard F. Calichman, in Takeuchi, What Is Modernity?, 46.

Takeuchi Yoshimi, “The Question of Politics and Literature (Japanese Literature and Chinese Literature I),” trans. Richard F. Calichman, in Takeuchi, What Is Modernity?, 86–87.

David C. Engerman, foreword to The God That Failed, by Richard H. Crossman (New York: Columbia University Press, 2001), vii–xxxiv. See also Frances Stonor Saunders, The Cultural Cold War: The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters (New York: New Press, 2000).

Takeuchi Yoshimi, “Kurossuman hen Kami wa tsumazuku” (Crossman, editor, The God That Failed), Ningen 5, no. 12 (December 1950): 148–49.

On Koestler’s visit, see Edward Seidensticker, Tokyo Central: A Memoir (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002), 87–91.

Hirano Ken, “An Antithesis,” trans. Junko Yamazaki et al, Politics and Literature Debate in Postwar Japanese Criticism, ed. Ueda et al., 87-92; this passage appears on 88-9. For the original Japanese, see Hirano Ken, “Hitotsu no hansotei,” Shinseikatsu, May 1, 1946, 183.

On Buck, see Klein, Cold War Orientalism, 123–35. On Mears, see Shibusawa, America’s Geisha Ally, 61–63.

When Keene traveled to London in 1940, Trilling provided a letter of introduction to E. M. Forster. See Donald Keene, Chronicles of My Life: An American in the Heart of Japan (New York: Columbia University Press, 2008), 70.

See the expression of gratitude to McClellan for editorial assistance in Friedrich Hayek, The Constitution of Liberty (1960; repr., Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011), 42. McClellan’s pathbreaking translation of Natsume Sōseki’s Kokoro, published in 1957 by the conservative Henry Regnery Company, was produced to allow Hayek to read one of the works taken up in McClellan’s dissertation, “An Introduction to Natsume Soseki: A Japanese Novelist” (Committee on Social Thought, University of Chicago, 1957). Prior to his encounter with Hayek, McClellan had studied with another seminal figure of American conservatism, Russell Kirk, author of The Conservative Mind (1953). See Hirotsugu Aida, “The Soseki Connection: Edwin McClellan, Friedrich Hayek, and Jun Eto,” 2008.

On Seidensticker’s work with the CCF, see his Tokyo Central, esp. 87–95. Seidensticker’s correspondence and receipts for salary and travel expenses with the CCF are archived in the papers of the International Association for Cultural Freedom, series IV, box 11, Special Collections Research Center, Regenstein Library, University of Chicago. Scott Charles, one of Seidensticker’s main correspondents at CCF, is identified as a CIA agent in Saunders, The Cultural Cold War, 243.