Abstract: Unlike the United States and elsewhere, political comedy is rarely spotlighted in Japan. Through interviews with three comedians, Hamada Taichi, Yamamoto Tenshin (The Newspaper) and Muramoto Daisuke (Woman Rush Hour), this article seeks to understand the practice, reception and standing of political humor in Japan today. What has motivated these comedians to pursue controversial routines that may have hindered their careers? How do they account for the relative lack of political satire in Japan today? The interviews provide a complex picture of media self-censorship and indirect pressure from the government – a picture that is both pessimistic and hopeful for the future of political satire in Japan. Interviews are edited for clarity.

Keywords: Political satire, performance comedy, censorship, media, political pressure

Introduction

The 2020 season finale for the popular American comedy show Saturday Night Live opened in a decidedly different manner than past episodes. For one, the opening skit was a parody of high school graduations held via the online video conferencing application Zoom. The Covid-19 pandemic, along with lockdowns, social distancing, masks and more, had even altered the way comedy programs produce content. Because of the crisis, SNL was forced to film their final three episodes remotely at different performers’ homes, instead of their usual live studio in New York. One thing that remained the same, however, was the presence of “Donald Trump” (as portrayed by Alec Baldwin). Responding to Barack Obama’s positively received online graduation address, SNL’s version of Trump talks to high school graduates as their eighth choice for a speaker. He begins by muting all the African-American graduates who disagree with him, touting exciting new job opportunities like “grocery store bouncer, camgirl, porch pirate, amateur nurse, and coal,” and dispensing advice like “surround yourself with the worst people you can find, that way you’ll always shine” and “never wear sunscreen.” He even takes a swig of Clorox when he starts coughing (a reference to his controversial suggestion of ways to treat the virus).1

Of course, such political satire is not limited to the United States. Down under in Australia, comedians on YouTube regularly satirize the conservative administration in the form of “honest government ads.”2 In England, along with comedians who regularly address politics in their routines, television shows such as The Mash Report3 (similar in style to The Daily Show in the US) satirize politicians even while being broadcast on the government-run BBC. Similarly, Germans can tune in to Heute Show4 to see the government and other figures get their humorous comeuppance. In France, citizens until recently5 could tune in to see their leadership parodied in the form of grotesque puppets on the show Les Guignols de l’Info.6

Unlike their Western counterparts, Japanese politicians are rarely satirized on stage, television or radio, despite ample evidence of corruption, scandal, incompetence, and lagging popularity due to the ongoing pandemic.7 Even social media lacks sites specializing in telling jokes to power. Through interviews with three of the small number of Japanese comedians who focus on political and social issues, I seek to understand why political comedy is rarely attempted and even more rarely televised. Here, I talk with Hamada Taichi and Yamamoto Tenshin of the political skit group The Newspaper, and more briefly, conduct an interview with Muramoto Daisuke of the manzai duo Woman Rush Hour. What do they think of the lack of topical comedy, and why do they choose to focus on the hot button topics that few others dare to touch? What emerges is a complex environment of self-censorship, with only indirect pressure from the government. Moreover, while many predict a grim future for political satire, Muramoto hints at possible changes to this bleak assessment.

1. The Newspaper

When I began to research manzai and expressed interest in political humor, people, without fail, referred me to the skit group The Newspaper (Za nyūsupēpā). The repeated recommendations are both a testament to the group’s longevity in the world of political satire, and evidence of the limited number of comedians in the genre. I eventually made contact with two veteran members of the nine-person troupe, Yamamoto Tenshin and Hamada Taichi, when they were performing in Tokyo. The following section is from an interview that took place in August 2016.8

|

Yamamoto Tenshin and Hamada Taichi after a performance in Tokyo (October 2019) |

The Newspaper was formed in 1989, just after the death of the Showa Emperor had cast the nation into a period of mourning and self-restraint.9 At the time, entertainment events involving comedians, musicians, and other performers were cancelled, leaving many entertainers without work. Yamada and Yamamoto, along with those who would later become members of The Newspaper, found themselves with time on their hands. With the simple goal of snapping people out of their grief by making them laugh, the group decided to use the news as a source for material, but they did not initially limit themselves to politics.10 Eventually the group settled on making fun of politics and certain politicians who continuously came up in the news.11 The interview with Yamamoto and Hamada lasted for ninety minutes, touching on many issues. For clarity, I have broken the interview into the different topics addressed.

The Problem with Topical Material

Why, I asked, did so few comedians “do politics” in Japan, essentially leaving them with no rivals. Here is what Yamamoto and Hamada had to say.

Yamamoto: I thought we were lucky to come up with the idea of using the newspaper as a source for our themes. When we would run out of ideas about what to cover, we could just go to the newspaper to find a theme and start from there. It changes every day, with news about politicians, economics, sports, entertainment, etc.

De Haven: A treasure chest of themes?

Yamamoto: Yes. That’s why I thought we were lucky to think of it. With that source, we can just use whatever is in the news at the time. And six months later, the news is completely different. So, we have to make new material. We thought, “Using the newspaper as our source for topics is limitless. This is great!”

De Haven: While many American stand-up comedians won’t do the same material once they have done it on television, many Japanese comedians in places like Asakusa seem to use the same material often. That has its good and bad points.

Hamada: Actually, at our live shows, we continually work on new material, and of course, in the news, certain politicians always come up. Doing those politicians who come up in the news all the time has become a trademark of The Newspaper. Nobody else does that. We have no rivals.

De Haven: Why do you think that is?

Yamamoto: In the end, I think it is because it is a bother. Our style of work is very inefficient. As Hamada said, usually comedians (in Japan) work on their material by doing the same thing over and over again, looking for what gets laughs, sometimes taking years to get an eight-minute routine just right. In our case, by the time we do something several times, the audience has forgotten that news story. So, no matter how high the quality of the material…

De Haven: You cannot do it anymore, like someone who does a great Reagan impersonation.

Yamamoto: Yes, exactly. So this is a really inefficient and tiring job. Also, even if you are good at doing an impersonation of a certain politician, you have to keep up with the news, studying today, tomorrow, next week and beyond, understanding how the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) is, knowing their history and so on. Because you have to keep up with and understand the news, reading the newspaper and so forth, other comedians do not want to do it.

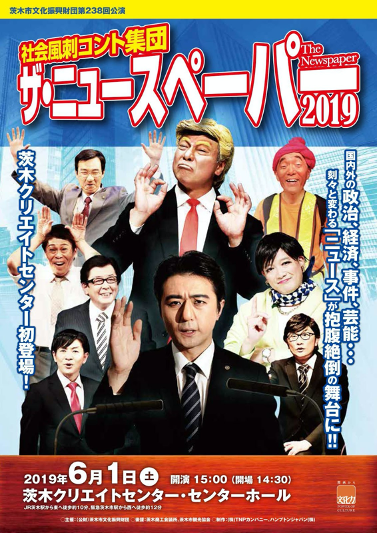

|

A flyer from a 2019 performance of The Newspaper.12 |

The Media Reception of The Newspaper and Political Material in General

Throughout the interview, the question of the lack of political humor on television and the possible reasons behind it recurred. Yamamoto was blunt in his assessment.

Yamamoto: To be honest, the media doesn’t like the kind of comedy we do. That’s why we can’t get on television. It is difficult for television directors to praise us because we deal with politics. They want middle-of-the-road comedy. Because there are right and left in politics, they are afraid of dividing Japan (or the audience) and that is why they do not use “dangerous” comedians. That is why you do not see satirical comedy or skits on TV that often.

De Haven: That seems a shame.

Hamada: But in Japan at least, that is the way it is with television.

Yamamoto: We went to one highly rated television show once and asked, “Please let us come on the show.” We made a DVD for them with political skits, easy to understand ones, and they said, “No way.” We did that two or three times, but they turned us down each time and we were not able to appear (on the show).

Hamada: If we did a normal skit that is not biting, but kind of soft with a news story that doesn’t focus on one specific politician, it would probably be okay, but we prefer to do something sharp with politicians in it.

Yamamoto: Of course, if there was a producer or director like you on a TV program, I’m sure we’d be able to get on TV. Because there isn’t anyone like that, it is very hard to get on air.

De Haven: There is the concern of sponsors as well.

Hamada: Yes, everyone is scared.

Unlikely Fans and the Stance of The Newspaper

After addressing what Yamamoto and Hamada believe are some of the reasons why The Newspaper and other political comedians are not seen on television, they revealed that they have some unlikely fans.

Yamamoto: Actually, it is not on television, but we are often called on to perform at events for everyone from the Communist Party to the Liberal Democratic Party.

De Haven: When you go, for example, to the Communist Party’s event, do you make fun of them in your comedy?

Hamada: Oh, yes, yes.

De Haven: Do they laugh at themselves?

Yamamoto: Yes, they do. That’s our stance. We make fun of left and right.

De Haven: Making fun of everyone equally?

Yamamoto: Yes. In our group, some of the nine members lean to the left, some lean to the right. That is the nature of our group. The Newspaper’s stance is that we do not lean left and we do not lean right. Our number one priority is to express the viewpoint of the common citizen. This is why we get called on to perform at LDP parties.

De Haven: So you have not felt any pressure from the government or politicians, directly or otherwise.

Hamada: Actually, politicians feel that they have not really made it if we do not impersonate them.

De Haven: I see, as proof that they have become big politicians.

Yamamoto: Yes, as to whether they had become big (and whether they had quit), those are among a select famous few.

Hamada: One Diet member said that, “Once you have been impersonated by The Newspaper, you have made it.”

Yamamoto: Ha ha, a Diet member really said that!

Hamada: So conversely, there is no pressure on us (from them).

Yamamoto: In that way (through becoming a comedic target), their name gets out there and they become well known.

Hamada: So there is no direct pressure (from politicians), just the opposite. They are supporting us.

De Haven: That is very interesting. That goes against all the assumptions I had made coming into this interview.

The Role of The Newspaper’s Comedy Plays in Society

As the interview continued, I tried to better understand the group’s motivations and how these two members saw their comedy’s role in society.

De Haven: Although I do enjoy manzai and skits, I still have the feeling that the comedians might be missing out (on more politically themed comedy). What role do you think comedy plays in society? What is its function?

Yamamoto: Well, it (comedy) has to be a gasu nuki (a release of gas).

De Haven: What do you mean?

Yamamoto: Gasu nuki means a release of stress. For example, just looking at a Japanese politician, people may think, “That’s strange/not right!” “That’s not true! “That’s not constitutional!” Or “That’s not what protecting the constitution means!” Comedians hit on that outrage (with their material) and people go, “Ah! I knew it!”

De Haven: They can identify with that or feel that their point of view is being heard.

Yamamoto: Yes, they can feel that connection and the laughter from that connection relieves stress. That is what we mean when we call comedy a gasu nuki.

De Haven: People can be brought to realize things as well through this comedy. “I knew that (something that they pointed out) was strange!”

Yamamoto: And when such laughter is released, it relieves stress and the performers have fun as well. It is kind of a feeling of “I was waiting for that!” That and the overall effect is what makes performing live so enjoyable.

De Haven: Okay, but taking it a step further, do you think that comedy like this has the power to move and change society?

Yamamoto: Maybe it does. After all, politicians, big ones including Diet members, do often secretly come to the shows. Maybe some of them see our comedy, write some things down, take it home and do something with it. I think they probably use it when they speak. There are probably some politicians like that.

De Haven: That is not exactly what I mean. It is interesting to hear that some politicians may be copying you, but what I am referring to is changing the direction of the way things are going.

Hamada: Well, there have been cases of comedians becoming politicians, being elected and moving Japan in that way.

De Haven: Like Higashikokubara?13

Hamada: Yes, exactly. Further back, Yokoyama Knock14 and other such people from the comedy world came out, got elected, and shaped society in that way. In the end, the way to move Japanese society is to become a politician. Currently, it is impossible for a comedian to change society. We can make people laugh, but that is it. To really change the world, you have to have a certain status. You cannot do that unless you become a politician.15

De Haven: In the case of the United States, the host (at the time) of The Daily Show, Jon Stewart, would make news stories into comedic material, bring issues to people’s attention. Those people would then contact their local politicians about the issue. Sometimes this resulted in laws being passed.

Yamamoto: This is not about whether politicians cause change in Japan, but a while ago, The Newspaper had this signature gag in which the top US and Japanese officials met, and the Americans were always putting pressure on Japan. I think this joke really shows the Japanese soul. The Americans were always demanding a clear “yes or no” answer, but at the most important moment, when the Japanese have to answer, “Yes or no,” they say, “Or!” I think that skit kind of sums up the Japanese soul.

De Haven: That certainly is an interesting aspect of Japanese culture, but from a foreigner’s perspective, it is frustrating to not be clear about something. That is why some would say that the Japanese can’t be trusted.

Yamamoto: Because of this, politicians would say, “The Newspaper said this!” and it was often used as an example showing the Japanese national character. So, I guess politicians pay close attention to what we do. I do not know if we could move Japan in one direction or another, but we are able to point out what seems strange from the viewpoint of the average Japanese person and get a lot of laughs from it. Look at the Abe administration…in 2015, the LDP had this study, which stretched the interpretation of the constitution, so that the right of collective self-defense was deemed constitutional. Anyone could see that it was a sham. You bring it up in the comedy routine and declare, “That’s strange!” and then someone in the audience lets out, “I knew it! You thought so too!” In moments like those, I think, “I’m so glad I’m doing this!” To educate, to bring feelings like this to the attention of politicians feels great and makes me feel that perhaps we have moved the needle a little.

De Haven: I would love for you to do such material on television.

Hamada: Impossible. Impossible. Impossible. That’s just not possible.

De Haven: Still, I would like to see material like tonight’s show.16 After all, the 300 people you performed in front of tonight seemed to enjoy it. It is nice that you were able to perform in front of so many people, but why can’t such shows be broadcast on television?

Hamada: Yes. If there was someone at the television network brave enough to do that, but there’s really no one like that there.

De Haven: How about NHK (the state-sponsored channel)? Ha ha!

Hamada: Yes! I mean, there is the BBC right? And they have programs using puppets as politicians!

De Haven: Ah, yes. You mean Spitting Image. In the past, they made some really ugly puppets depicting Reagan and Thatcher.

Hamada: I thought it was amazing that they were allowed to do that and on the (state-sponsored) BBC at that!

The Future

De Haven: So, as The Newspaper, what is your goal? What does the future hold?

Yamamoto: Well, as I said earlier, we are not trying to change Japan through The Newspaper’s comedy. Right now, we take the contradictions of politicians, the “isn’t this strange” parts and hugely deform them, changing these moments into comedy. Of course, the more people that come out to shows, the more we enjoy our work and we would like to increase these chances as much as we can.

|

Manzai duo Woman Rush Hour (Muramoto on the left; Nakagawa Paradise on the right)17 |

2. Woman Rush Hour

In December 2017, the comedic duo Woman Rush Hour took the stage on the popular annual television program, THE MANZAI, and delivered a five-minute routine that, to the surprise of everyone watching, touched on a wide range of sensitive political and social issues. The routine’s content and the subsequent widespread reaction in the mass media and on SNS led me to interview Muramoto Daisuke, who writes the duo’s routines. The specific routine and Muramoto’s further efforts to widen the boundaries of what is acceptable in manzai has added significantly to the debate surrounding political satire in Japan.18

Despite not graduating from high school, Muramoto carved out a successful career as a manzai performer. After going through a series of different partners, Muramoto formed the manzai duo Woman Rush Hour with Nakagawa Paradise in 2008. The duo went on to win several awards including THE MANZAI 2013, the most prestigious televised contest between manzai duos in the country.19

Before reviewing Muramoto’s statements on political comedy in Japan, let us summarize the comedy routine that has won him both accolades and scorn from the media, other comedians, and the public on SNS. In the routine, one member of the duo plays a person who wants to live in a certain area (Fukushima, Tokyo, Okinawa, etc.). This person (played by Nakagawa Paradise) is questioned by a resident of that area (played by Muramoto), and has to prove his love for the area so that he is deemed worthy of being allowed to live there. While interviewing the prospective resident, Muramoto covers a range of problems that the area is dealing with. The following, for example, is part of the routine where Nakagawa is trying to move to Okinawa.

Muramoto: What problems is Okinawa dealing with right now?

Nakagawa: The relocation of the US base to Futenma problem.

Muramoto: What else?

Nakagawa: The Takae heliport problem.

Muramoto: Those are problems for just Okinawa to deal with, right?

Nakagawa: No, those are problems that all of Japan has to deal with.

Muramoto: And the Olympics that will be held in Tokyo?

Nakagawa: Something that all of Japan will celebrate.

Muramoto: And the Okinawa military base problem?

Nakagawa: Something foisted off on Okinawa only.

Muramoto: And fun things are?

Nakagawa: Something for all of Japan.

Muramoto: Troublesome things are?

Nakagawa: Something we pretend not to see.

Muramoto: And how much are we paying the US military to stay here?

Nakagawa: 9,465 million yen.

Muramoto: And what is that budget called?

Nakagawa: The sympathy budget.

Muramoto: Before we show sympathy to America, we should…

Nakagawa: Show sympathy to Okinawa!

Muramoto: Welcome to Okinawa! You may live here!

Finally, after covering a wide range of topics at high speed, Muramoto shifts focus to Japan in general. Like the other places covered in the routine, Nakagawa starts out by asking for approval to live in Japan, and Muramoto, playing the part of a Japanese person who will test Nakagawa’s devotion, questions him.

Muramoto: What problems is Japan dealing with now?

Nakagawa: The revitalization of disaster areas (after the Great Fukushima earthquake, tsunami and nuclear meltdown).

Muramoto: What else?

Nakagawa: The nuclear power plants problem.

Muramoto: What else?

Nakagawa: The Okinawa military base problem.

Muramoto: What else?

Nakagawa: The North Korea missile problem.

Muramoto: But what’s actually covered by the news?

Nakagawa: Politicians’ verbal gaffes.

Muramoto: What else?

Nakagawa: Politicians’ affairs.

Muramoto: What else?

Nakagawa: Celebrities’ affairs.

Muramoto: Are those really important news stories?

Nakagawa: No, they’re just superficial problems.

Muramoto: So why do they become news?

Nakagawa: Because they get good ratings.

Muramoto: And why do they get do ratings?

Nakagawa: Because there are people who want to watch them.

Muramoto: So what we really should be worried about is?

Nakagawa: More than the disaster area recovery problem –

Muramoto: More than the nuclear power plant problem –

Nakagawa: More than the Okinawa military base problem –

Muramoto: More than the North Korea problem –

Nakagawa: Is the low level of awareness shown by the citizens!

(Audience laughs)

Muramoto: (speaking into the microphone and pointing at the audience) I’m talking about you people!

|

Muramoto directs his criticism at the audience, “I’m talking about you people!”20 |

Sitting Down with Muramoto Daisuke, Another Voice in Political Satire

By performing a routine that touched on many serious issues rarely addressed in comedy on a nationally televised program, Muramoto Daisuke emerged as a new voice of political humor. I was able to sit down with Muramoto in March 2018 to talk about his motivations and the state of political satire in Japan, along with a range of issues. Although the interview was brief, this discussion, along with other interviews that Muramoto has conducted with the media, statements from his solo shows, and his comments on social media conveys the impression of a comedian taking his material into controversial waters by Japanese standards.

|

Muramoto Daisuke speaking with the author (photo provided by author) |

The interview began with an inquiry into the future of his political comedy.

De Haven: Will you continue to do political comedy like what we saw on THE MANZAI?

Muramoto: Actually, I probably will not. At a recent show I did, I received a threat – one guy told me to “go to hell,” and this made me think about my safety and the safety of those working the shows with me. There have been cases of politicians and others in the past being stabbed by people on the right and that worries me a bit. I also might receive pressure from sponsors, so I will probably not use such material in the future.

One person at my show who paid to see me walked up to me afterwards and demanded to know why I didn’t apologize immediately on TV for saying that Okinawa was once part of China.21 I tried to explain to him that that was not how TV worked. This kind of response made me afraid for my staff.

Muramoto then went into the differences in how political humor is handled in the US and Japan.

Muramoto: It is completely different in the US. Producers protect their comedians (from pressure from sponsors, the public, etc.) and television is set up differently. There are NETFLIX and cable television, with comedians getting specials and being able to say whatever they want.

De Haven: So, what are your goals with this brand of comedy? What would you like to accomplish?

Muramoto: I want someone deep in the mountains, in some far-off place in China, to be afraid of discriminating against someone because they might be made fun of by Muramoto. If someone says something (discriminatory) like that, anywhere in the world, I want him or her to be scared that they will become the butt of my joke. I want people from around the world to take notice. I want people who might use violence or might discriminate to be scared that they will become the target of Muramoto’s humor. Also, I want to joke about things that no one ever jokes about or think they cannot possibly make humorous. I want to make jokes that are so funny that people laugh so much that they forget their anger. It does not matter if it is the Emperor, the Queen, or the Pope. I want to poke fun at them, making them laugh so much that they are no longer angry or irritated.

De Haven: And after the laughter what would you like to happen?

Muramoto: The laughter is enough.

De Haven: Do you want to change peoples’ minds?

Muramoto: Not at all.

De Haven: Not at all?

Muramoto: No, not at all. I do not want to change anyone’s mind. What is important to me is that my humor not be placed in a “special class.”22

De Haven: Special class?

Muramoto: Yes, special class. In Japan, there are special classes, for example, someone with a disability is meaninglessly sent to a separate school. With my comedy, there is no special class. It does not matter if you are rich, or the Emperor, or the Queen, or even a blind person, I want to target everyone with my humor and if I can do that, I will be happy.

De Haven: And you would like to do this in English as well? Why is that?23

Muramoto: Yes, I want to do this in English. The reason why is if I speak Japanese, there is only Japan. If I can speak English, more people speak that language, so I can make more people laugh. That is why I want to do comedy in English (as well).

Coming Back to The Newspaper: Reaction to Woman Rush Hour’s Political Material

Finally, in an effort to clarify some of their positions and get their reaction to the sudden emergence of Muramoto Daisuke and his politically charged routine, I reconnected with The Newspaper’s Yamamoto Tenshin and Hamada Taichi, a few months after Woman Rush Hour’s appearance on television.

De Haven: I’d like to talk with you about Woman Rush Hour’s routine on television recently. It really became big news. Did you watch it when it was broadcast or afterwards?

Yamamoto: I recorded it and watched it later, and when I did, it really struck a chord with me. I thought it was amazing.

De Haven: Because it touched on topics that were not addressed before?

Yamamoto: Yes, of course, because of that, but also because when I saw the routine, it seemed to be a flashback to the beginning of The Newspaper. We are now celebrating our 30th anniversary as a unit, but what I saw (with Woman Rush Hour) looked a lot like what we did in the beginning, in the way he went about it and how he served as a voice for the common man. I really felt it deeply. There were not that many places to laugh in the routine, but he really made something great and to be able to broadcast it on television, I was just like, “Wow.” In the beginning, The Newspaper was very anti-establishment, critical of the government and such, but as time went on, we became less so as a group. Hamada and I were two of the founding members and performed with them for about 20 years or so, but we took a break from them for a while and then returned. And when we came back, the make-up and stance of the group had changed. While in the past, most of the members leaned left, in tune with the times, the group shifted with members on the left and right. I think that has led The Newspaper to have a balanced show.

De Haven: But in the beginning, you were not so balanced?

Yamamoto: We were not. So, when I saw Woman Rush Hour recently, I thought, “That’s it! That’s our origin!” It was a bit shocking, so I watched it five or six more times.

De Haven: And he (Muramoto) covered so much that is not usually talked about in such a short time as well. I have never seen a manzai routine covered in the news like that.

Yamada: Actually, The Newspaper used to do routines like that. To put it simply, those are called local routines. Those are jokes that locals or people from that area would laugh at, not the whole world, but pinpoint areas like Okinawa. When we went to different areas, we would do localized material as well. Actually, I think it is amazing that such local material could be broadcast on television. In the past, because of restrictions, that would not be broadcast.

De Haven: Because it is too localized?

Hamada: Because it is too dangerous. With the nuclear issue and such, and the criticism of the locals (audience) and others, but actually, this time, Muramoto was able to make those people laugh. And with that laughter, he was able to say, “Boy, you people are stupid!” and that got an even bigger laugh. It was a pattern where they were criticized and then they laughed at themselves.

De Haven: I am not sure what local people thought, but the public laughed, and then, he pointed to the audience and said, “The biggest problem is the low level of awareness shown by everyone! I’m talking about you people!”

Hamada: Yes, yes. To be told that actually feels good too, surprisingly.

One more thing was that the audience was occupying the same space, which is strange to say, but that is why they all felt, “Yes! That’s true! That is strange!” That is why they laughed (understanding the absurdity of their own position). That is why that produced laughter. If you make a wrong step, though, you could get in big trouble (as a comedian). People might say, “What are you talking about!?” or “Don’t say such stupid things!”

Why Muramoto’s Political Material Did Not Resonate More

Yamamoto: You know that routine by Muramoto really got to us, but do you know why it did not make more of a wider impact?

De Haven: Is it because of pressure from television stations?

Yamamoto: There is probably some of that, but actually, the reason it did not resonate more is Prime Minister Abe’s approval rating. Right now, his ratings are high enough that he can do (almost) anything and get away with it. I mean, after all, even with the recent Ministry of Finance scandal, his ratings have not fallen. If those ratings fall, Muramoto’s cry of, “It’s you!” would actually lead somewhere. However, public opinion isn’t there. For Hamada and me, that routine was right down our alley. “Well said! You are amazing!” That is not where public opinion is.

De Haven: Well, there were many who praised the routine, people who were moved deeply by it, but not everyone liked it.

Hamada: You can never have 100% of the people. Never.

Yamamoto: But the interesting thing about public opinion is that it goes to the right, and then it goes to the left, right, left, in that order. After a war starts, public opinion is more motivated to stop it, but after a while, with the passage of time, people forget that pain gradually.

De Haven: And those that felt it first-hand grow old and die.

Yamamoto: Yes. And right now, that order is flowing to the right. Looking all over the world, it is shifting to the right. That is why Muramoto’s routine does not have that extra power to it. If that kind of routine were done 20 or 30 years ago, it would have had a great impact. We think it is a pity that it does not seem to match the mood right now.

De Haven: But if Abe’s approval rating was around 30%, it would have had more power?

Yamamoto: It would be huge. I mean, with the scandal in the tax office, the officials finally admitting wrongdoing, and the Ministry of Finance with the Moritomo Gakuen scandal,24 that should be enough for an administration to…

De Haven: …be finished.

Yamamoto: It should be finished, right? If it keeps going like this, the approval ratings should go down and public approval should be at its lowest. And if that happens, there will be a situation where someone has to take responsibility. The head of the party is Abe, but there does not seem to be any such movement, from the mass media or otherwise. And the mass media is not doing their part and putting out this news.

Earlier you were asking if television stations put pressure on us or not, but around the time when we (Hamada and Yamamoto) were going to quit The Newspaper, the rules for television news were very strict. Before then, we had gone on the daytime talk show Tetsuko no heya once every year or two, but during that period, we stopped appearing on the show for five years. We were finally able to get on the show recently, but the tendency has been to bar satire from television.

De Haven: Is that sontaku (a Japanese word recently used to describe self-censorship or restraining oneself in an effort to please those in power)?

Yamamoto: Yes, of course. If we do get on television, it is on cable.

De Haven: Yes, and that is a bit different (from shows broadcast on terrestrial television).

Yamamoto: And who is responsible for this environment now? Well, you can partially blame the mass media. And, as always, we (The Newspaper) turn things into laughter.

The Future of Political Satire in Japan

I asked Yamamoto and Hamada about the future of political satire in Japan.

De Haven: So, looking at the big picture, do you think that political humor will change in the long term after Woman Rush Hour’s routine?

Hamada: After the administration changes, I think it will change. If the party in power changes from the LDP to another party, it may change.

De Haven: And do you think the way people think about political humor will change?

Hamada: The material changes with the times. So, for example, there are currently not a lot of jokes with bite to them, but it is possible (with change) that that kind of humor could emerge more and more.

De Haven: If the LDP loses power?

Hamada: Abe has been in office for a long time now and without changes (in the government), The Newspaper and our material does not change. For example, if the Prime Minister changes, our members would change.

De Haven: Would your members change?

Hamada: Yes, because a different member would impersonate the new Prime Minister. When the administration changes, so do the people in the group who impersonate them.

De Haven: I see. There certainly are not many chances to impersonate Obama, are there now? (Hamada played the former President)

Hamada: Ha ha, not at all now! If (the political world) changes, so will we. If it does not, neither will we.

De Haven: And if the economy25 is going well in Japan, people are like, “Well, I guess things are fine the way they are”?

Yamamoto: That is exactly it.

De Haven: If your wallet isn’t hurting…

Yamamoto: Yes, yes. That is why public opinion is where it is now. Hamada and I do not have a chance.

De Haven: A chance for bigger exposure?

Yamamoto: Yes, just as I am always bringing up. For example, when elections come around, there are always rankings listing what is foremost in the voter’s thoughts, and in that list, the economy always comes out on top. In the end, the economy always equals your wallet. Money is the most important, after all, right? Otherwise, you wouldn’t be able to live. Ultimately, more than the US military bases, how you are going to make ends meet tomorrow is more important, right? With the primary concern on the economy, support for the Abe administration remains constant because things are pretty stable economically. Abenomics is getting better and better. So, if you are doing fine, who cares about the nuclear power plants or the US military presence? “Oh, something dropped? Oh, well.” It has nothing to do with me. The US military bases are over there. That is why the best time for The Newspaper is when things are at their worst. When the economy is bad, when people are dissatisfied, that is when The Newspaper can exert our strength the most.

De Haven: So that is why if Woman Rush Hour did their routine in more troubled times, more people might say, “Something is wrong here!”?

Yamamoto: Yes. And to go back to Woman Rush Hour’s routine, when Muramoto says, “I’m talking about you!” at the end, what he is saying is if people don’t raise their awareness, they won’t be able to understand what he is saying. And that might be a rough way of saying so, but right now, people living normal lives are eating steak and sushi, and thinking that they are basically happy, right? Economically, if you work, things will be good and that’s that. Whether it’s the US bases or the nuclear power plants, that’s not a concern for people, and these people are the “You!” that Muramoto is addressing, I think.

De Haven: So political humor and the number of those who do it will not increase?

Yamamoto: No, they won’t increase. You can’t eat (make a living) while doing it.

Hamada: The numbers won’t increase. You won’t be able to eat doing it. It is a tough time (for political satire).

Motivations and Being Careful Not to Cross that Line

As the interview wrapped up, it touched on what Yamamoto thought was “going too far,” and once again, their motivation for doing satire.

De Haven: So, other than The Newspaper, well, there is the group Owarai Beigunkichi (Laugh: American Bases) in Okinawa, but they only perform there, and there’s no one else doing political satire.

Hamada: Yes, that’s true.

De Haven: In the United States, I would be able to quickly come up with the names of five or six political comedians off the top of my head because there are so many. But in Japan…

Hamada: There isn’t anyone.

Yamamoto: That’s why I feel I have to be careful when I’m doing satire. I am, for the most part, a left-leaning person, anti-government. I really want to defeat power, defeat the government. So, my approach is to make people laugh at power.

De Haven: Yes, that kind of humor has been around for a thousand years.

Yamamoto: Yes, that is true. But, for example, if 90 to 100 percent of the audience are anti-government, I think that would be a bit scary. If that is the case, I think that goes beyond comedy and becomes a kind of activist group.

De Haven: Yes, like some sort of political movement.

Yamamoto: If the ideology becomes too strong, I think that’s dangerous. Even I, as a left-leaning person, think that is dangerous, which is why we have a stance where half the group is from the left, half the group is from the right.

What we do doesn’t have to do with right or left. We take the viewpoint of the common man and make comedy from that. It’s as simple as that.

The reason we are satirizing is really for the purpose of stress relief (gasu nuki). When we turn all the unpleasant things that people have to think about into comedy material, “That manager is an idiot, isn’t he?” “Yeah, he sure is!”, it gives the people a release and that moment brings happiness. That moment of happiness has nothing to do with left or right, and if you can reach that level where everyone regardless of politics can laugh, it is truly a great thing.

De Haven: So, you don’t want to change society, right?

Yamamoto: No, we are not thinking about that at all.

Hamada: Actually, it’s like the weak bullying the strong. We bully those in power with satire.

Conclusion

This paper features three wide-ranging interviews with two different parties from the small pool of comedians in Japan today, both seeking to satirize politicians and touch on sensitive topics that others avoid. I went into these interviews with essentially three main questions. First, why is there a lack of political satire in Japan today (especially compared to the United States)? Second, for the few who do choose to do political satire, what are their motivations? Why did they choose a path that potentially limits their appeal? Finally, what role do they think this type of comedy has in society and how do they see their part in this world?

Despite their different performance styles and years of experience in the genre, both Yamamoto and Hamada of The Newspaper and Muramoto of Woman Rush Hour shared overlapping opinions about the dearth of satire in Japan. Both cited a lack of backbone among television networks and producers, and while neither pointed to direct governmental pressure, it appears that the Abe government has contributed to an environment of self-censorship among television producers and comedians in general. This lack of opportunity to perform satirical comedy on television would no doubt dissuade comedians from even attempting such risky topics. Moreover, the need to continually update comedy routines in order to stay current, along with the general public’s apathy towards politics and society indicate that the deck is stacked against political comedians.

Furthermore, this scarcity of television appearances may also explain some politicians’ “support” for The Newspaper, despite their being targets of the group’s comedy. Without many opportunities to go on television, the chances of The Newspaper gaining a wider audience and perhaps influencing (or at least giving voice to) public opinion are minimal. Therefore, in setting a show or a private performance at a political party event, politicians can enjoy being made fun of with little fear that satire will damage their overall image. Politicians can be “in” on the joke, without having to worry too much about being the “butt” of the joke. During the recent Sakurai no kai scandal,26 Fukumoto Hide, a member of The Newspaper famous for impersonating Prime Minister Abe, found himself face to face with Abe and his supporters at the cherry blossom-viewing event itself. Abe supporters found it amusing and even Abe seemed to give permission for his impersonation, but added that it should be done “moderately.”27

So, if there were so little reward, why would a comedian in Japan choose to focus on political and other sensitive issues? Surprisingly enough, at least in The Newspaper’s case, according to the members interviewed, the initial motivation to perform satirical, political comedy arose from a need for a constant source of material, and not from a desire to precipitate social change. The Newspaper saw a market for those who could express popular frustrations in a comedic form and ran with it, choosing not to be the voice of the liberal or conservative point of view, but that of the public. Focusing on live stage performances, The Newspaper has cultivated a loyal fan base that clearly believes that political satire does have a place at the table, even if television producers do not share that point of view.

Muramoto, on the other hand, who sites rebellious comedians such as Lenny Bruce, Richard Pryor, and George Carlen as an influence, and wants to be free to target any and all groups or classes with his comedy, including politicians and sensitive societal issues. He also seems to want to target those who might discriminate against or others, such as Okinawans or victims of the Fukushima disaster. Muramoto seems to enjoy the challenge of targeting difficult subjects and turning them around so that people can laugh and forget their anger.

Finally, when the interview subjects were asked how they thought their comedy would affect society, both parties maintained a similar perspective, not believing that their comedy could change society or not wishing to change the world through their routines. Both the members of The Newspaper and Muramoto (at least partially) saw their brand of humor as a vehicle for release of public frustration or discomfort regarding a specific topic. Yamamoto and Hamada further noted that, in their opinion, only comedians who ran for political office could effect change, and that a comedy show more closely resembling a political rally is a scary prospect, one that crosses a line between comedy and activism.

Nonetheless, there are signs of change. The Newspaper recently celebrated its 30th anniversary. Since his shocking political routine two years ago, Muramoto and his two-man group, Woman Rush Hour, have performed controversial material twice on the annual, widely watched television program THE MANZAI, drawing its share of supporters and detractors. Much like The Newspaper, the Okinawa-based Owarai Beigun Kichi28 has entertained audiences annually. The latter’s humor touches on Okinawa’s unique and difficult position on the American military bases, particularly the contested Marine base under construction at Henoko. In addition, a small number of younger performers such as Takamatsu Nana29 and Seyarogai Ojisan30 have begun to make an impact with political satire or related material on stage and online.

Moreover, it may well be that the 2020 Covid-19 pandemic will, in spite of its ravages, have a positive impact on the role of political satire in Japan. In their interviews, the comedians were somewhat pessimistic about the future, especially considering the lack of access to television. Yamamoto and Hamada saw hope only if economic conditions somehow took such a downturn that Prime Minister Abe would be forced to step down. For them, popular dissatisfaction could increase the influence of political comedy. Their comments were made in 2019, when Abe was riding high. Now, with the prime minister’s popularity at an all-time low over his inept response to the pandemic and the economy’s downturn, conditions should have significantly improved for political satire. Given its dependence on live performances, however, The Newspaper has not been able to take full advantage of public dissatisfaction. All of the group’s stage shows have been cancelled for the foreseeable future. Beginning in mid-July, however, The Newspaper began to record and release several political skits on Amazon Prime for rental viewing.

Woman Rush Hour has fared somewhat better. Even before the pandemic, Muramoto noted that comedians who touch on politics and society in Japan needed to change their way of delivering creative content. Specifically, he urged a move towards the kinds of streaming platforms available in the United States. During the pandemic, Muramoto has shown himself to be adept at these newer forms of mass media. He appears regularly, for example, on AbemaTV, a 24-hour internet television station. In addition, he has moved his near-weekly solo performances, which originally took place all over the country, to the online meeting application Zoom. For a small fee, viewers can see Muramoto perform live from the comfort of their living rooms. Whether these small pockets of change will give way to a more mainstream movement remains to be seen, but the Covid-19 pandemic may well be a turning point in the long history of political satire in Japan.

When looking at the production, motivations for, and reception of political satire in Japan in comparison to the U.S. and the rest of the West, it is all too easy to fall into the trap of “why isn’t Japan like that?” when there are differences in culture, media environment and historical background. At the same time, however, the interviews show that comedians in Japan are aware of and take cues from the outside world of political humor. Looking back at the interviews, some comments deserve more scrutiny, especially when the comedians’ opinions came in conflict with each other. Indeed, how comedians present themselves and their work should not be taken strictly at face value and should be balanced out, at least, with reactions from their audiences. Nonetheless, one thing is clear from these interviews: despite its relatively lower visibility, political satire has a place in Japan, and despite (or even because of) the challenges of the Covid-19 pandemic, the place and future of political satire in Japan is brighter than ever (or at least, open to more possibilities). Thanks to the passion of these and other comedians, as well as the audiences who support them, the future of this comedic genre is one that warrants further research and discussion.

Notes

“This is what Brexit REALLY means! German political comedy “heute show” (English subtitles).” Accessed June 20, 2020.

After nearly thirty years on the air, Les Guignols de l’Info was cancelled in 2018 by the Canal+ network. For more on this see here.

Although the television show was cancelled in 2018, the show continues to have a presence on YouTube. See here.

With the poor handling of Covid-19, Prime Minister Abe has seen his popularity drop to 27% in a recent (5/23/2020) poll. See here.

Although topical humor involving the news in the West is quite common, many comedians in Japan tend to focus on more general themes.

“Shakai fuushi konto shuudan THE NEWSPAPER 2019, Ibaraki bunka shinkō zaidan,” Accessed April 14, 2020.

Before successfully running for governor of Miyazaki prefecture, Higashikokubara Hideo had a career as television personality and comedian from 1982 to 2006, serving as comedian/film director Beat Takeshi’s first apprentice. He went under the name Sonomanma Higashi.

Yokoyama Knock was a prominent comedian and television personality who successfully ran for political office, serving as a Diet member and later, as the governor of Osaka Prefecture.

Recently another comedian, Oshidori Mako, also known for her freelance journalism and activism over the nuclear disaster in Fukushima, ran for political office in 2019 as a member of the Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan but lost.

Before interviewing the members of The Newspaper, the author saw a performance by the duo at Asakusa Engei Hall.

For general recap of the media’s and public reactions, to Muramoto’s comedy routine, as well as a link to the performance, see my website. Other reactions to the political routine can be found here, here, and here.

Screenshot from the video of Woman Rush Hour’s appearance on THE MANZAI 2017. To see the full performance, see here.

On his January 1, 2018 appearance on the late-night political debate program Asa Made Nama Terebi 2018 Gantan Special, Muramoto caused some controversy when he mistakenly stated that Okinawa was once part of China. The comment drew some backlash from personalities on the right, as well as from people from Okinawa.

Muramoto here uses the term 特別学級 (tokubetsugakkyu) which can be translated as a special class or special needs class. He also uses it in an unusual way when referring to whom he targets with his humor. This usage could be interpreted as special treatment (when it comes to who are targets of his humor).

At the time of this interview, Muramoto had just returned from a trip to the United States, where he studied English with the hopes of performing abroad.

Because this interview took place well before the Covid-19 pandemic, this section on the stability of the Japanese economy may feel out of place, but I feel it sheds further light on how The Newspaper links political comedy’s popularity to dissatisfaction with the economy.

The Sakura no kai is an annual event that invites people from the public and private sectors to appreciate the cherry blossoms, and converse with the Prime Minister and other government officials. Recently, it has come under scrutiny from opposition parties as a waste of public funds and a way for Abe to reward his supporters. For more details, see here.

For more information on Owarai Beigun Kichi (in Japanese only), see: here or here.

Jon Mitchell also mentions the group in his article published in this journal.

Originally a solo comedian (pin geinin), Takamatsu Nana has recently shifted her efforts to producing political satire and workshops with a focus on educating young people about politics and solving societal problems through humor. More information can be found at her company’s website.

Seyarogai Ojisan is a comedian based in Okinawa who has recently found a following on YouTube with videos that humorously point out problems with governmental policies, societal issues, and more. Some of his more popular videos have garnered over 600,000 views. His rants are also featured on a national morning show every Friday. His videos can be found here.