Abstract: The COVID-19 situation in Thailand may be less worrisome in comparison with other countries, but it would be a mistake to celebrate this as the outcome of effective state policy. On the contrary, the Thai case debunks an assertion that an authoritarian approach manages COVID-19 better. Instead, it demonstrates the failure of the government in tackling the pandemic as a result of its short-sighted top-down approach, incapable state agencies, and the lack of investment in healthcare and medical science. Furthermore, COVID-19 has drawn Thailand even closer to China for assistance in this time of pandemic crisis, carrying the potential to shift the balance of power further against the United States.

In March 2020, the World Health Organisation announced that the coronavirus, known as COVID-19, was classified as a global pandemic. As of June 2020, the virus has affected more than 6.8 million people worldwide and about 400,000 have died. In Thailand, there are fewer COVID-19 cases than in some other Asian countries, with 3,100 confirmed cases and 58 deaths. State agencies quickly took credit for containing the pandemic, but it appears that there is significant underreporting. Thais have voiced discontent about government policies designed to consolidate authoritarian governance rather than genuinely tackle the virus. Currently, Thailand is ruled by the government of General Prayuth Chan-ocha. Prayuth was the leader of the 2014 coup that overthrew the elected government of Yingluck Shinawatra. He remained in power for the next five years, and in 2019, called for an election through which his reappointment as prime minister was legitimised. His cabinet is replete with ex-generals and their cronies, entrenching the military’s position in Thai politics. This illustrates the reality that Thailand’s government, albeit democratic on the surface, is deeply rooted in authoritarianism. Its policy on COVID-19 has thus reflected its predominantly dictatorial nature.

This essay debunks arguments that have claimed authoritarian regimes perform better in times of crisis, an assumption based on their ability to rapidly mobilise national resources for emergencies (Chen 2016, Ch.9). An example in support of this claim might be the Chinese government’s swift response to the 2008 Sichuan earthquake, where it gathered massive medical teams within one day. However, it is unwise to treat every crisis as alike: in reality, each requires specific solutions. Despite China’s ability to swiftly respond to the Sichuan earthquake in 2008, it is evident that China struggled to control the spread of COVID-19, and its initial blocking of important information on the pandemic and rewriting of the virus narrative to conceal its mismanagement has outraged the global community. By addressing Thailand within this framework, the implications and public response to COVID-19 policy under the Prayuth administration paint a picture of failure rooted in authoritarianism. Much like other dictatorial regimes, the Thai government is most concerned with maintaining regime stability and ensuring their own survival by means of surveillance and suppression at a time when public health should be paramount. The Prayuth administration’s approach to grappling with the advancing global pandemic proved to be ineffective.

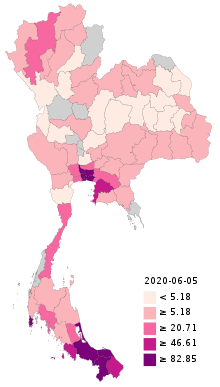

Map of provinces with confirmed or suspected coronavirus cases (as of 30 May). Source. |

Failure to Launch

Its incompetence in managing the COVID-19 crisis reveals the failure of the government to prove itself a credible and trustworthy regime. From the beginning, the government failed to pay attention to the outbreak, instead caught in contentious politics marked by nationwide protests against previous injustices. Students from universities across the country participated in demonstrations against the government, initially for its dissolution of the young Future Forward Party in February 2020, simply because that party was perceived to be a threat to the regime. Furthermore, the students were unhappy with the military’s enduring influence in politics as well as the continued political intervention of the newly crowned king, Vajiralongkorn. This political upheaval in the early days of the COVID-19 crisis dulled what should have been a sense of emergency. The first COVID-19 case was reported in Thailand on 13 January 2020. The response from the state agencies was lacklustre, even ignorant, illustrated best by the comments of Minister of Public Health Anutin Charnvirakul that it was just another simple flu (Teeranai 2020). On 31 January, the first local transmission was reported. Yet, even this failed to alert state authorities or stimulate them to develop preventive measures against the virus.

From January to February, the number of cases remained low although the government had neither sealed the borders nor enforced a lockdown. Both visitors from China and Thais returning from affected countries were allowed entry without health checks at Bangkok airports. In March, there was a surge of COVID-19 cases. Several transmission clusters erupted, one of which was a Muay Thai match at the Lumpini Boxing Stadium on 6 March. Confirmed cases rose to over a hundred per day over the following weeks. By then, public venues and businesses in Bangkok and nearby provinces had been instructed to shut down. The government slowly began to understand the seriousness of COVID-19, but failed to stop the spread. It was not until the end of March that the Prayuth government come up with comprehensive anti-virus measures, as follows:

- Focusing on surveillance and contact tracing

- Setting up temperature and symptom screening booths at all airports and hospitals

- Investigating outbreak clusters

- Promoting public education focused on self-monitoring for at-risk groups, practicing hygiene (such as mask wearing and hand washing), and avoiding crowds

- Closing down schools and non-essential businesses

- Enforcing self-quarantine for those returning from overseas

- Imposing travel restrictions

- Requiring medical certification for international arrivals and health insurance for foreigners

- Launching Thai Chana [Thai Winning] Project to educate the public on the prevention of COVID-19

But these measures were inconsistent, confusing, and at times even in conflict with one another. For example, while the government seriously enforced strict quarantine and self-isolation for Thai workers coming home from South Korea, it continued to permit entry to tourists from South Korea without subjecting them to quarantine. Government officials played a blame game with both the opposition and medical experts. Health Minister Anutin caused uproar when he denounced doctors and nurses who had become infected by COVID-19 during off-duty hours as irresponsible and bad role models for the public. The level of Thai people’s mistrust of the authorities reached an all-time high.

|

Thai Chana Project Source: Chainwit/CC BY-SA |

Prime Minister Prayuth declared a state of emergency, in effect on 26 March. A week later, on 3 April, a curfew was announced: Thais were not allowed outside their home from 22:00 until 04:00. Alcohol was not sold during this period. Immediately, the added authoritarian regulations were met with public discontent. The curfew was bound to fail in preventing the spread of COVID-19 because Thais were still free to do as they pleased without practicing social distancing during the daytime. Incidentally, the announcement of the state of emergency and curfew, as well as the sudden closure of Bangkok businesses, caused thousands of workers to travel back to their hometowns, jeopardising public health across the country. This underlines the failure of state authorities to coordinate a unified response against the virus. The curfew is supposed to remain until the end of June, but many in Thailand believe it is mostly an effort by the government to thwart political protest than to prevent the spread of COVID-19.

Poster informing those returning from China. Source: Chainwit, CC BY-SA 4.0 |

Regime Attacked

Thailand has succumbed in the past to a number of trans-national diseases, including SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) in 2002 and the Avian influenza (Bird flu) in 2013. During those periods of health crisis, Thailand was under the democratic governments of Thaksin and Yingluck, respectively. Thailand even played host to the SARS Summit in April 2003, bringing together leaders from ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations), China, and Hong Kong to find a breakthrough to the crisis. However, in 2020, the authoritarian rule under Prayuth has meant policy and response to COVID-19 are also intended to strengthen the power of the government in the face of growing public frustration. Evidently, the measures taken have both failed to contain the virus and further eroded public trust. There are three major areas in which the government’s incapability has been exposed. First, the authoritative nature of COVID-19 policy was inadequate in dealing with a non-traditional threat to national security, and instead took a counterproductive role. Second, the character of the regime, namely in prioritizing political control over the health and safety of the public, played a major part in thwarting what could have been chances to curb the virus spread. Research and development in medical and health sciences that would have equipped those industries and related state agencies to respond promptly to the virus lacked investment. The presumptuous and indifferent attitudes exhibited by the state agencies caused them to treat it like a typical seasonal illness that would soon disappear. Consequently, it was not, and the Thai government’s incapacity to face the transnational pandemic became frighteningly clear. Third and finally, COVID-19 has exacerbated tensions between the United States and China, putting Thailand in the awkward position of having to choose sides. COVID-19 has, in many ways, attacked the regime, exposing the weaknesses inherent in its authoritarian strategies which failed to handle the health crisis and protect Thai people.

An Authoritarian Design

The assertion that an authoritarian regime is especially capable in mobilising resources in times of crisis is debatable. Transparency and the free flow of information are essential but not a hallmark of authoritarian regimes. As Victor Pu argues, “To correct information about the infectious patients’ location and their TOCC (travel, occupation, contact, and cluster) requires rapid reports from individuals, hospitals, and local governments to the central command centre” (Pu 2020). He also adds that this rapid sharing of crucial information assisted not only in controlling the pandemic, but also in the ability to implement responsive policies as quickly as possible. Thus, controlling the spread of a virus requires the free flow of information and ability for the public to share information, an approach which challenges authoritarian regimes’ tight controls on information. In the Thai case, the information on the number of COVID-19 tests has been vague. The government’s COVID-19 Information Center claimed that, from the beginning of the year until 8 May, it had tested 286,008 people, of which 3,017 were found to be infected. However, the total number of test cases has never been verified by independent organisations.

Owing to the nature of the Thai regime, it is apparent that Thailand followed an authoritarian model in dealing with COVID-19. The curfew in particular harked back to the coups of the past, when it was used as a tactic for dominating society and undermining opposition. The government’s anti-COVID-19 policy can be characterised as top-down, officious, and even patronising towards doctors and nurses. As the pandemic reached its peak in March and April, the government imposed an extreme quarantine for those arriving at the Suvarnabhumi Airport – all were transported to an empty naval base in Satthahip for a two-week isolation. On top of this, the Prayuth government also attempted to apply quarantine tactics to public discussion surrounding the pandemic. Any blame directed towards the government was taken as fake news. Thais did not and do not have full access to information about the pandemic; there are no real-time updates on affected cases, numbers of deaths, or those recovering from COVID-19. Nobody knows how many cases are tested a day. When a famous Facebook page, Mam Pho Dam [Queen of Spades], revealed evidence of possible corruption by government associates regarding a missing stockpile of masks, the woman running the page was interrogated by the government. Tilting towards authoritarianism, the Prayuth regime strove to silence the public in order to guarantee its own stability.

The palace also partook in Thailand’s pandemic diplomacy. In January 2020, the king sent a telegram of sympathy to Chinese President Xi Jinping on the epidemic caused by coronavirus (Chinese Embassy, Bangkok 2020a). A month later, King Vajiralongkorn dispatched medical products and equipment to China as a gesture of goodwill, all while Thais had no access to such products (Matichon 2020a). Vajiralongkorn, ascending to the throne in 2016, has since been criticised for spending most of his time residing in Germany’s Bavaria, rather than staying home in Thailand. Furthermore, while many countries had closed their borders, Vajiralongkorn booked the entire Grand Hotel Sonnenbichl with special permission, breaking the lockdown in the alpine resort town of Garmisch-Partenkirchen. But he was not alone: he isolated alongside a harem of 20 women (Brown 2020). The controversy was not kept within the confines of the alpine hotel. On 5-6 April 2020, Vajiralongkorn flew back to Thailand amidst the no-fly policy, prompting the Thai government to close the airport in order to accommodate his visit. He was tasked, in Bangkok, with the commemoration of Chakri Day, the day the Rattanakosin dynasty was founded. His decision to disregard what virus safeguards were in place for a short event that lasts less than one day, compounded with his other eccentric lifestyle choices, have stirred resentment against Vajiralongkorn, particularly among the younger generation. They took to Twitter to voice their disapproval of the king, causing the hashtag #มีกษัตริย์ไว้ทำไม or #WhyDoWeNeedKing to trend in Thailand for days, with more than 1 million tweets (Berthelson 2020). The actions of the king flaunted the ugly reality that the privileged in Thailand are exempt from the government’s rules.

A further shortcoming was found in the government’s coronavirus policy. Its authoritarian approach failed to take into account the economic consequences of closing businesses. These closures, plus the banning of public gatherings and forcefully imposed curfews, directly hurt the people at the lowest rungs of society. These people were struggling to make ends meet and blamed the government for their inability to protect the poor not just from COVID-19, but also from economic hardship caused by the virus and its poor management. To calm the situation, the government adopted a policy of distributing 5,000 baht ($162) per person, initially saying the handouts would continue over a period of six months. As it turned out, the cash handout only lasted for one month. Causing further trouble, the online payment process was clumsy and complicated, resulting in some people waiting several days before their registration could be accepted. Also, not everyone was eligible to claim their share of the handout. The unreliable and irregular distribution of funds greatly infuriated some of the poor who were deemed ineligible, and they responded by protesting at the Ministry of Finance to demand immediate cash relief. To make matters worse, a 59 year-old woman, distraught over her situation, attempted to commit suicide by swallowing rat poison. (Bangkok Post 2020). This was not the only tragedy. A few days after complaining about economic difficulties on her Facebook page, another woman hung herself; her note was found alongside her drawing of Prayuth’s face, as if she wanted to blame him (Thai Rath 2020). A group of Thai academics conducted research on the suicide rate of Thais as a result of COVID-19 and found that, over the period from 1 to 21 April, there were 38 suicide attempts. Of these, 28 died and 10 survived. Astonishingly, within the same period, the number of Thais killed by COVID-19 also stood at 38, suggesting that the government’s policy which by and large ignored its economic impacts was seriously flawed, putting many poor Thais at risk and further tarnishing the government’s image (Poor City in Crisis, 2020).

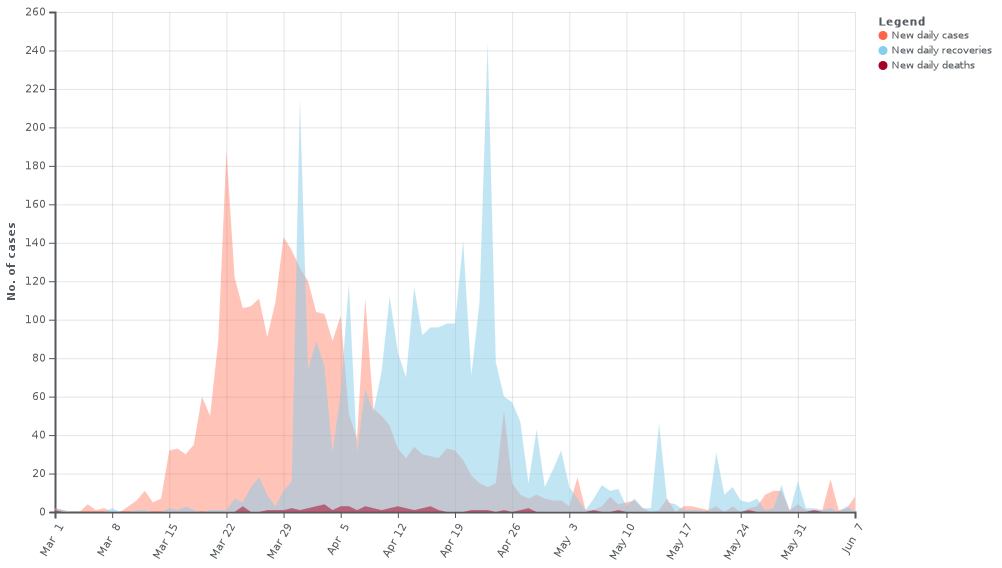

Number of cases: Orange colour represents new daily cases, which has decreased drastically overtime. Blue represents new daily recoveries. Red represents new daily deaths. Source. |

Unfamiliar Territory

The composition of the Prayuth cabinet is representative of the root cause of the government’s failure in coping with COVID-19. Authoritarian regimes of the past had survived several crises because they relied on capable individuals and experts in different fields, as well as able technocrats to help direct policy. In today’s Thailand however, many cabinet members are either retired generals or cronies of the regime. Of the individuals and agencies that would be seen as commanders in the fight against COVID-19, including the prime minister and other ministries, none had experience facing a non-traditional threat to security. They lacked knowledge and understanding of the pandemic, a price that would be paid by Thai people.

As prime minister, Prayuth displayed a sorry lack of leadership and an inability to address or even see the bigger picture. Instead, he continued to conceptualise the crisis as a military threat, personifying COVID-19 as if it were a visible enemy, as seen when he reassured Thais, “We must win the fight.” This statement reflects a kind of military propaganda rather than real tangible policy vis-à-vis COVID-19 (The Nation 2020). Feeling cornered, Prayuth called upon the top 20 richest men and women in Thailand to help support the government financially (CNA 2020). In the end, none committed anything to the government. Health Minister Anutin continued to embarrass both himself and the government by disparaging medical employees and oversimplifying the virus situation. He announced, “Thailand is a superpower of healthcare,” which was then ridiculed by the public as an exaggeration (Bhumjaithai 2020). Minister of Commerce Churin Laksanavisit clearly failed to stabilize the price of necessary commodities during the lockdown, and neither could he mitigate the shortage of products, such as face masks, anti-bacterial creams and gels, and gloves. Minister of Finance Uttana Savanayon, who leads the ruling Palang Pracharath party, made headlines in Bangkok as the amount of suicides reached an unprecedented number. In June, there were rumours he would step down as the party’s leader in order to pave the way for General Pravit Wongsuwan, the deputy prime minister, to take the helm.

While all of these cases are notable, the most notorious scandal involved 200 million missing medical masks, a much sought-after product and healthcare necessity. The likely truth behind the missing masks was uncovered by popular Facebook page Mam Pho Dam, which held Duty Agricultural and Cooperatives Minister Thamanat Prompow responsible. His only response was to deny that his assistant Pittinant Rak-iad had anything to do with a hoarding of masks for resale to China (Apinya 2020). However, his words are difficult to take as truth considering Thamanat himself was once convicted in Australia for drug trafficking, resulting in a four-year imprisonment. Interrogated by the opposition in the parliament about his past, he replied, “It was not heroin, it was flour” (Ruffles and Evans 2020). Instead of investigating the hidden hoard of face masks, the police went after the owner of the Facebook page for uncovering the scandal, accusing her of damaging the reputation of the government.

With mounting complaints about the lack of access to practical information on COVID-19, the government set up the Centre for COVID-19 Situation Administration (CCSA) and appointed psychiatrist Thaweesin Wissanuyothin as its spokesperson. At the beginning, the CCSA was praised by the public for its part in providing essential information about the pandemic. But the praise soon evaporated because the CCSA, too, turned authoritarian. Thaweesin became perceived as a politicised figure who served mainly the interests of the government rather than prioritising the COVID-19 crisis. The list of complaints against Thaweesin’s controversial statements is substantial. In one instance, he asserted that the 5,000 baht cash subsidy was adequate, supplementing Thai lives that are already made convenient by the abundant natural vegetation. “People can pick vegetables grown on their fence and live comfortably”, he said (Matichon 2020b). Subsequently, when a bus driver died of COVID-19, Thaweesin made the disparaging remark, “I did not know a woman can drive a bus.” His sexist attitude provoked the ire of The Student Union of Thailand, who protested against him (Student Union of Thailand, 2020). To make matters worse, as the number of Thais committing suicide increased, Thaweesin defended the government by stating that the number of suicide cases due to COVID-19 was still much lower than it was during the financial crisis in 1997, prompting public condemnation for his lack of empathy (Khaosod 2020). He has certainly become a divisive figure, and those supporting the government responded to criticisms against him by launching campaign #SaveThaweesin on Twitter.

A transnational pandemic is an unfamiliar enemy for those in power in Thailand. As noted above, the political leaders’ backgrounds created a narrow worldview within the government, where national threats could only be defined in “traditional” terms, such as war, armed conflict, territorial dispute, or defence of sovereignty. In fact, for decades, Thailand has paid little heed to the more significant non-traditional threats to security like natural disasters, pandemics, and environmental degradation. The budget for the promotion of public health has remained low. The country lags behind others in the region, for example Singapore, in terms of investment in the medical and health sectors. Instead, since the advent of Prayuth as prime minister in 2014, the defence budget has continued to grow at a rapid pace. It is true public health spending has grown steadily too, but the increase has been smaller compared with the defence budget, as seen in the table below (Ministry of Public Health 2020):

|

Year |

Defence Ministry (billion baht) |

Public Health Ministry (billion baht) |

|

2014 |

184 |

99 |

|

2015 |

192 |

108 |

|

2016 |

207 |

120 |

|

2017 |

214 |

125 |

|

2018 |

220 |

130 |

Thailand has long been a regional hub for drug trading. The country has one of the highest rates of HIV in the Asia Pacific, accounting for 9 percent of the region’s total population of people living with HIV. The Boxing Day Tsunami in 2004 served as a wake-up call for Thailand’s security establishment in its need for preparedness to cope with natural disasters as the latest kind of non-traditional threats (Pavin 2011, 58-60). Despite all of this, the current regime has failed to recognise the seriousness of the transnational pandemic. The crux of the problem lies in the mindset of the military, which remains fixed in the Cold War era.

Infecting the US-Sino Rivalry

Southeast Asia, particularly Thailand, has been a crucial front in the struggle for influence between two major world powers: China and the United States. Thailand is a military ally of the United States – a relationship forged during the Cold War when both nations identified a common enemy in communism. As a result, Thailand has for years implemented a pro-US, anti-communist, pro-military policy, serving as a client state of the United States. But US departure from the region in the aftermath of the Vietnam War paved the way for a new friendship between Thailand and China, solidified when the two countries established diplomatic relations in 1975. What followed was a rapid development of Thai-Sino ties, alongside an established alliance between Thailand and the United States. The rise of China in the recent decades has intensified the competition between Beijing and Washington, the result of which has forced Thailand to proceed with caution and adjust its policies to accommodate the two powers as much as to reap the benefits from them.

The pandemic has, in some ways, reconfigured the Sino-US competition into one where China has an edge over the United States. It is true that China was ground zero of the virus outbreak but it has also been busy rewriting the virus narrative to obscure this fact. Meanwhile, the United States has had to concentrate entirely on defending itself from the virus, which has ravaged the country with almost 2 million confirmed cases as of June 2020. The pandemic has exposed an inconvenient truth: both the United States and China, like Thailand, were not well prepared for this type of non-traditional security threat. It has also challenged the competency of their leadership in crisis. Ian Storey and Malcolm Cook argue that COVID-19 is likely to aggravate the concerns of Southeast Asia regarding the Sino-US rivalry. The lack of cooperation between the two powers in handling the pandemic has not only deepened the region’s distrust in them, but also exacerbated their negative images (Cook and Storey 2020, 2-7). For the United States, the scale of devastation has been too overwhelming, preventing it from initiating solutions beyond its borders. This lack of international presence by the US has played directly into China’s hands. As the country first attacked and first to recover from the virus, China has been able to reach out to its neighbours in an attempt to repair the negative image it developed as the source of the pandemic, particularly via the use of soft power. China dispatched medical supplies to Thailand in April, as confirmed by its embassy in Bangkok (Chinese Embassy, Bangkok 2020b). The hand extended by the Chinese in this critical time harks back to China’s assistance to Thailand in the aftermath of the financial crisis in 1997, when it offered a financial bailout to help stabilise the Thai economy. The message these actions send is powerful: in times of crisis, Thailand can always rely on its Chinese friend. Yet for Thailand, the growing level of reliance on China means little room for foreign policy manoeuvres, particularly at the time when the United States seems disengaged from Southeast Asia. Although the Thai leaders know they cannot fully trust Beijing, they have little choice but to maintain friendship considering that the power and dependability of the United States has declined.

Conclusion

The argument which favours authoritarian regimes in times of crisis for its centralized management and ability to swiftly mobilise national resources is deconstructed in looking at the failures of Thailand’s own authoritarian regime. Instead, the shortcomings of the Thai government bring to light how responses built on democracy have done a much better job in containing the virus, such as in Taiwan. In the context of COVID-19, a free flow of information is crucial in safeguarding public health, but the Thai case unfortunately follows in the footsteps of other authoritarian regimes in its utilisation of a top-down approach aimed at controlling the public as a means to controlling the pandemic, which backfired. The Prayuth government is seen clearly to have initiated a series of policies primarily aimed at its own selfish goals of maintaining regime stability and dominance. The target of Prayuth’s government’s policy was not COVID-19, but control and suppression of Thai people. When Thais responded with rightful complaints about the mismanagement by the government, they were silenced. Some who were left out of the subsidy scheme protested by committing suicide, which served to further tarnish the reputation of the government.

The failure of the Thai government takes many forms. The government’s policy is intrinsically dictatorial, from its implementation of a curfew, to uneven segregation of the poor from the rest of the country. Furthermore, there are few capable individuals in the government who could understand the seriousness of the pandemic. Ex-generals occupying top political positions whose frame of thought is confined within their military expertise were not the right people to lead the country against this non-traditional threat. As a consequence, Thais had to live with a government which condoned lies, corruption, and the politicisation of the COVID-19 situation, and which refused to acknowledge its neglect of public health. Meanwhile, on an international level, COVID-19 has further fuelled an already intense competition between the United States and China, which has drawn Bangkok closer to Beijing through the latter’s soft power, all while Washington is preoccupied with fighting on its own soil.

References

Apinya Wipatayothin. 2020. “Thamanat Denies Aide Involved in Massive Mask-Hoarding”, Bangkok Post, 9 March.

Bangkok Post. 2020. “Woman Downs Rat Poison Outside Finance Ministry”, 28 April.

Berthelsen, John. 2020. “Thailand’s Controversial King Outrages Subjects”, Asia Sentinel, 6 April.

Bhumjaithai. 2020. Anuthin Longphuenthi Cho Samutprakarn Porchai Robobkadkrong Rok COVID Pluemprathetthai Penmaha Amnaj Dankarn Satharanasuk [Anuthin Visiting Samutprakarn Province, Satisfied with COVID Management, Happy for Thailand Achieving the Status of Superpower in Healthcare], 27 April.

Brown, Lee. 2020. “King of Thailand ‘Isolates’ from Coronavirus with 20 Women”, New York Post, 30 March.

Channel News Asia. 2020. “Thailand PM Asks Rich for Help with Coronavirus Fall-out”, 17 April.

Chen, Gang. 2016. The Politics of Disaster Management in China: Institutions, Interest Groups, and Social Participation, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, Chapter 9.

Cook, Malcolm., and Storey, Ian. 2020. “Images Reinforced: COVID-19, US-China Rivalry and Southeast Asia,” Perspective, No.34, Issue (24 April), pp.2-7.

Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the Kingdom of Thailand. 2020a. “King Maha Vajiralongkorn of Thailand Sent a Telegram of Sympathy to President Xi Jinping of China”, 1 February.

__________. 2020b. “The Chinese Embassy in Thailand Donates Medical Supplies to Various Thai Institutions”, 5 April.

Matichon. 2020a. “Nailuang Phrarachatan Wechaphan Hai Chine Namsongprom Kruangbin Rap 149 Khon thai Krabbaan” [“The King Offered Medical Equipment to China, Together with Send a Plane to Bring Home 134 Thais”], 3 February.

__________. 2020 b. “Kosok Sor Bor Tor Manchai Ngern 5 Pan-u Tor Chor Wor Dai Sabai Meepaksuankrua Kindai” [Spokesman of COVID Taskforce is Confident 5,000 Baht Handout Cash Makes Comfortable Life for People], 9 April.

Khaosod. 2020. “Kosok Sor Bor Tor Tobpom Khon Katuadab Chung COVID Chee Mainua Khwamkadmai”, [Spokesman of COVID Taskforce Answered to the Case of People Committing Suicide, Not Surprising”], 30 April.

Ministry of Public Health. 2020. (Accessed 1 May 2020)

Pavin Chachavalpongpun. 2011. “Years of Loving Dangerously: Thailand’s Current Security Challenges”, Security Outlook of the Asia-Pacific Countries and its Implication for the Defense Sector, NID Joint Research Series No.6, pp.58-60

Poor City in Crisis, COVID-19. 2020). 24 April. (Accessed 30 April 2020)

Pu, Victor. 2020. “How Democratic Taiwan Outperformed Authoritarian China”, Japan Times, 2 March.

Ruffles, Michael, and Evans, Michael. 2020. “Thai Minister Who Pleaded Guilty in Sydney Heroin Case now Says ‘It was Flour’”, The Sydney Morning Herald, 3 March.

Student Union of Thailand. 2020. 14 April. (Accessed 1 May 2020)

Teeranai Charuvastra. 2020. “It’s Just a Flu: Health Minister Insists Coronavirus under Control”, Khaosod English, 27 January.

Thai Rath. 2020. “Arai Saowai 19 Vadphab Nayok Odratthaban Chairai Kriad Maimeengern Suenom Hailookkin” [“Commemorating a 19 Year-Old Woman who Drew a Portrait of the Prime Minister Complaining her Hardship not Being Able to Buy Milk for her Baby”], 29 April.

The Nation. 2020. “Thailand Must Win the Fight against COVID-19, Says Prayuth”, 16 March.

Thai Post. 2020. “Pued Tualek Ngob Kalahome Yonlang 16 Pee Prachan Nakkanmuang Pliplon Hasiang”, [“Unravelling Defence Budget in the past 16 Years, Condemning Politicians for Lying to the People”], 1 May.