Abstract: As COVID-19 spread across the United States, so did incidents of racial harassment and violence against Asian Americans which exposed uncomfortable truths about race relations in the United States. President Trump’s racist rhetoric and the spread of viral social media videos and posts created a heightened sense of danger, blame, and fear – making all Asians “Chinese” in the United States and potential targets for racial abuse.

In discussions and debates about race and racism in the United States, Asians and Asian Americans often have been left out or simply been uncounted (Smith, 2013). For example, until recently, many opinion polls would exclude us and only count whites, African Americans, and Latinx (Sanders, 2020; Agiesta, 2020; NBC/WSJ/Marist Poll, 2016) . If we were included, it was in the category “Asian” which included Northeast Asian, Southeast Asian, and South Asian members of our community, and did not differentiate us from each other or amongst newly arrived immigrants and Pacific Islanders. The argument was that we were too few in number (Smith, 2013; Holland and Palaniappan, 2012), and our marginality was reinforced in the media, government, business, public health studies, and other social spaces. Recently, political scientists have created resources to share disaggregated data of our communities so that scholars and policymakers alike can have a more accurate picture of our diversity, and the variations in our health, educational, and economic outcomes (AAPI Data).

Perhaps more importantly, in the last couple of years, Asian Americans and Asians of northeast Asian ancestry in particular began to break through in various industries and reach peak visibility. Examples include: Korean filmmaker Bong Joon-ho’s multiple Oscars for Parasite; Canadian-Korean Sandra Oh’s Golden Globe for Best Actress in a Drama TV Series for Killing Eve; Andrew Yang’s presidential bid; Awkwafina’s role in the star-studded Ocean’s 8 film, starring role in The Farewell, and her subsequent high-profile hosting of SNL and her later television series; Ali Wong’s spotlighted comedy specials and film on Netflix; the film Crazy Rich Asians breaking box office records; and the explosion of K-pop bands like BTS all over American television, computer, and cell-phone screens. All of these individual moments of visibility made it seem as if Asian Americans and Asians (of northeast Asian ancestry) had finally “arrived,” at least in the American entertainment industry and political arena. Just as we began to get caught up in this misleading sense of acceptance by America, the pandemic put us right “back in our place” and reminded us that America was and is not ready to acknowledge our full humanity and complexity, and would once again flatten us into one image: the perpetual foreigner, the COVID-19 carrier: a source of the anxieties, fears, and economic distress of multiple ethnic groups. All of us–Asians and Asian Americans–became “Chinese.”

We all became Chinese in the minds of some Americans who kept seeing and sharing COVID-linked sensational images and stories of Chinese people’s “strange” and “exotic” culinary preferences and their wet markets; some of these viral images and videos of foodies who ate bat soup in Indonesia, for example, were unrelated to COVID-19, but they made a lasting impression and gave Americans what they wanted to see to confirm their biases and stereotypes through memes and personal social media posts (General, 2020). These posts drowned out recent images that made Asians feel more seen and accepted by mainstream America. Soon, there was clickbait of racial baiting by everyone from the American President to professors and celebrities making it more acceptable to talk about “the Chinese” and Asians as filthy, disgusting, backwards, and diseased. There was no differentiating us, nor was there any reason to treat actual Chinese or Chinese Americans this way.

Comments and posts on various websites indicated that no one was going to protect or stand by us, and so we had to stand up for ourselves. Asian supporters of Trump and the GOP spoke out and asked their party leadership to address the racist rhetoric because of the danger posed to Asian Americans (Rogers, Jakes, and Swanson, 2020; Friedman, 2020). On the other hand, one candidate for Congress, Kathaleen Wall, framed her campaign around blaming China for “poisoning” the US. Senators John Cornyn and Ted Cruz, both representing Texas, also blamed China and Chinese culture for the pandemic (Wallace 2020). Volleyball coaches, PhD Candidates, and business owners were posting hateful content or perpetuating racist ideas linking China, COVID-19, and bats (General, 2020; Ke, 2020; and Samson, 2020). Memes and fake stories took on a life of their own and China was blamed for the pandemic.

Facebook groups, such as Crimes Against Asians and news outlets such as NBC Asian America, and Next Shark became an archive of racist posts and videos. The Asian Pacific Policy and Planning Council began the website page “Stop AAPI Hate” for the purpose of documenting these cases and offered an incident report in multiple languages (A3PCON, 2020). As these videos went viral, my news feed also became more populated with Asians throughout the US and the world sharing stories of harassment and verbal abuse, and then violence (Randall, 2020; Samson, 2020; Ke, 2020; General, 2020). Social media fueled a sense of fear, danger, and even hate among those who wanted to blame China and Asian Americans.

The pandemic reminded Asians that we could remain invisible in America as “model minorities,” but then become hyper-visible targets of racism by multiple ethnic groups overnight. This being said, as an Asian woman, I navigate life in the US with many privileges. I do not fear for my life when I drive, sit in a parked car, go jogging, or sleep in my own bed. I am probably more aware of my gender in calculating when and where I navigate public spaces. For the first time, however, I felt that all people saw was my race. People stopped sitting next to me on the train; white men and women would walk past my empty seat on my commutes even though the train car was packed. People would give me dirty looks and glare at me with anger and disgust. The stares became longer, harder, and more hostile, especially at the grocery store. White women seemed afraid and angry at me and did not even try to conceal it. One older white woman rushed to the end of the train when she realized I was standing behind her on my morning commute from Lancaster to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and dramatically pumped the hand sanitizer dispenser attached to the wall of the train car, pumping it furiously to wipe away any disease I might be carrying. She acted as if I was a contagion. I felt like other people were acting as if I was something to be feared and disgusted by. I think COVID-19 for many Asians, like myself, was the first time they understood what it was like to be reviled and profiled. That a random stranger felt justified in cursing at you, spitting at you, or attacking you because you look “Chinese”.

It got to a point, where I felt afraid to run simple errands or to even go out for a walk, and I felt anxiety about wearing a mask outside because at that time in March and April of 2020, masks were not mandated by the state and Americans did not understand this practice of wearing masks to protect others as they do in Asia. Asians wearing masks were targets for racist harassment and violence while grocery shopping. I wore sunglasses on my walks around the neighborhood with my (white) husband and avoided making eye contact. I began to literally walk with my head down and did not want to go out alone anymore.

I was afraid that people would blame me for the deaths in their families, loss of jobs, and the general malaise of having to shut down businesses because of COVID-19. Unemployment was rising, people were being laid off, and small business owners were panicking. By then, the Chinatowns were already deserted, and Asian restaurants were empty and often vandalized, even if they did not have any cases of COVID-19 (Chang 2020; Peavey, 2020). People didn’t seem to really notice or care that so many Asians, especially immigrants, would be losing their jobs. I did not see communities rallying to support these Asian owned restaurants and their Asian servers as I have seen since the state ordered closures and white owned local businesses would also be impacted. Many family businesses closed. The data shows that Asians unemployment rates increased significantly from last year, but in places like NYC, claims for unemployment by Asians increased by 6900% (Liao, 2020). Compared to other groups, Asians had a lower rate of overall unemployment at 2.5% in February but by May, it went up to 20.3% which is comparable to the rate for Latinos at 20.4% (Kochhar, 2020).

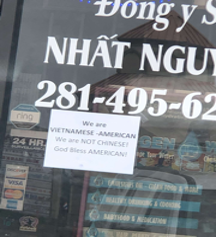

The President of our country and his party’s leadership blamed it all on China rather than our own government’s failure to respond in a timely and effective manner (Isenstadt, 2020). By blaming the Chinese, they were also making it so that those who appeared to be Chinese could be blamed in the US. Most Americans can’t tell Asians and Asian Americans apart or differentiate us by our languages and histories. Because of COVID-19, anti-Chinese sentiments and racism became more common and casual. We were not Asians or Asian Americans, but Chinese. By calling COVID-19 the “China flu,” the “China virus,” and “Kung-flu,” casual racism against us became more acceptable. Some Asians even began selling shirts proclaiming, “Not Chinese,” which is problematic in other ways, or posting signs that they were Vietnamese and not Chinese. We were told to our faces to go home or had our property vandalized (Peng, 2020). We were targets of hatemongering and racist abuse in the United States and world-wide (Human Rights Watch, 2020).

|

Sign announcing that the owners of this store are Vietnamese-Americans and not Chinese. (The image is from a screenshot of a post that was shared to Crimes Against Asians on facebook on April 9, 2020.) |

|

A family-owned Chinese restaurant had “coronavirus” and “COVID-19” with an arrow pointing at the front door and “Go home to China” spray-painted on their building and the sidewalk. ABC7 News, New Jersey. |

All of this made me consider how privileged we are, because our friends who are Muslims, Sikhs, Latinx and African Americans must make these calculations daily, hourly, and constantly. I remembered the day after the 2016 election, when my Muslim women students sobbed in my office and were afraid to go out and to take the train home for Thanksgiving break. They were afraid to walk to the train station in Lancaster, Pennsylvania because of their head coverings. We offered to walk with those students or drive them so they could reach their destinations safely. You would imagine this would heighten our understanding of privilege and compel us to think more about racism in our country. Now more than ever we have reason to probe into our own privileges and unconscious biases and begin to do some difficult but necessary work on these issues. Where were we as our Black, Muslim, and Latinx friends expressed their concerns and rage over the racism they encounter daily, especially under the Trump administration? Did we stand with them as we have now hoped they would stand with us?

We need to do this work despite the disheartening appearance of Latinx and African Americans in stories of assaults against Asian/Americans – often younger men physically assaulting older more vulnerable people like the elderly and women. The media was also profiting from our fear and I realized that even the social media groups forming to show us these videos and create awareness also risked simply amplifying our fear. These images of African Americans and Latinx attacking Asians unleashed bigotry from all sides. People of East Asian heritage then posted responses in kind, justifying why Asians can’t trust anyone and need to protect themselves—by arming themselves (ABC 7, 2020).

In all these ways, Asian Americans are being swept up into the signature pandemic of Trump’s America – the sowing of division. Trump and his party are using COVID-19 the way they use most issues: to further divide Americans from each other and the rest of the world. It feels like a particularly American tragedy that the event to help bring many Americans together was the viral video of a police officer killing an unarmed African American man. The murder of George Floyd, as well as the murders of Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbury, and incidents of “Karens” calling the police on African Americans just going about their lives now placed the anti-Asian racism in a more complicated context: no longer about Asian victims, but also Asians as perpetrators and accomplices, because one of the police officers who did nothing while his colleague killed Floyd is Hmong American. The ensuing protests for civil and human rights in the streets and the clashes with police have shown us that as much as Asians were inconvenienced, harassed, or attacked, few of us are murdered by the police for walking with a mask on or for minor traffic or driving offenses.

It reminded us of our position in American race relations once again, and how we must also fight anti-Black racism and examine the roles we play in perpetuating it. Asians have benefited from having businesses in minority communities. Latasha Harlins and the LA Riots are seared in our collective memories. The work of examining our own complicity in anti-Black racism is ongoing and feels even more urgent now. It is not enough to talk about our own struggles as Asians during COVID-19 when many African American and Latinx people have experienced racism perpetrated by Asians, including our own family and community members. I saw posts by African American and Latinx friends and colleagues saying that they did not owe Asians anything at this moment. There was no solidarity – only the painful truth that Asians are perceived to be in proximity to Whites and that Asians are complicit in these systems.

However, I also saw I had friends and colleagues on the ground, actively working to mobilize within their own ethnic groups and communities, as well as across groups to respond to the pandemic. Feminist resistance and mobilization countered the images of Asians as victims of hate and showed how young women were taking control of the narrative (Bhaman et al., 2020). I saw ethnic groups working together to help victims of COVID-19, Asian American activists and educators linking our fates to the Black Lives Matter movement and efforts to dismantle white supremacy and address anti-Black racism. I saw how multicultural coalitions of activists and educators created their own initiatives and resources to document, archive, and remember both the unique individual and shared experiences of this pandemic in the Asian and Asian American communities (A/P/A Institute, 2020; The AAPI COVID-19 Project).

The pandemic has brought America’s race relations to the fore, and Asians and Blacks feel racist incidents against them have increased (Ruiz, Horowitz, & Tamir, 2020). In the span of two weeks, there were 1,100 cases of anti-Asian racism reported, with more reports made by women than men (Chan, 2020). COVID-19 has exposed the vulnerabilities of different populations in the US. African American communities have very high mortality rates, and have suffered the greatest economic losses, while Asians and Whites had lower mortality rates. The disease replicated and followed the outlines of American economic and social stratifications, but also showed how Asians, once proximate to whiteness as model minorities, could easily find themselves the target of multiple groups’ expressions of ignorance, fear, and bigotry.

COVID-19 is a reckoning with America’s long history of racism, its exclusion of Asian immigrants, their persecution during the internment and restrictions on migration, but also a reckoning for Asian Americans who must confront their place in this society and continue the work of interrogating their own biases, privileges, and complicity in upholding a white supremacist society. If anything, COVID-19 has reawakened us to both the need for interethnic coalition building and solidarity and the need to fight even harder for racial justice, especially for Black Americans. The Asian American community remains divided, however, and not all Asian Americans have emerged from this experience sharing this outlook. We are not a monolithic group, and so the outcomes and impacts of this anti-Asian racism will reflect that, but the pandemic and anti-Asian racism remind us that our position in this country is tenuous, even after all these generations and hundreds of years in the US, and that America’s relationships with Asian countries, especially its tensions with China, will continue to link Asian Americans to Asians in Asia and the governments of Asia. The pandemic shows just how hard it is for many Americans to accept us as Americans.

This reflective essay does not represent the views of the Center for the Advancement of Teaching and is the author’s own personal opinion.

References

ABC 7. 2020. “Coronavirus News: NJ Chinese restaurant vandalized with racist COVID-19 graffiti,” ABC7 New Jersey, June 17. Accessed 20 July, 2020.

Agiesta, J. 2020. “CNN Poll: Trump losing ground to Biden amid chaotic week,” CNN. June 8. Accessed 20 July, 2020.

Bhaman, Salonee, et al. 2020. “Asian American Feminist Antibodies: Care in the Time of Coronavirus,” Asian American Feminist Collective collab. with Bluestockings NYC, Zine online. Accessed on 1 June, 2020.

The AAPI COVID-19 Project. Accessed 20 July, 2020.

AAPI Data: Demographic Data & Policy Research on Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders. Accessed May 1, 2020.

A/P/A Institute. 2020. “A/P/A Voices: A COVID-19 Public Memory Project,” Asian/Pacific/American Institute at New York University, collab. with Tomie Arai, Lena Sze, Vivian Truong, & Diane Wong, and NYU Tamiment Library & Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives. Accessed on 1 July 2020.

A3PCON. 2020. “Stop AAPI Hate,” Stop AAPI Hate Reporting Center, Asian Pacific Policy and Planning Council. Accessed 1 July, 2020.

Chan, L. 2020. “Reports of coronavirus related hate crimes against Asian Americans hit 11-hundred in two weeks,” Asian American News, April 2. Accessed on 10 May, 2020.

Chang, 2020. “San Francisco Chinatown Affected By Coronavirus Fears, Despite No Confirmed Cases,” All Things Considered on NPR, February 26. Podcast. Accessed on March 1, 2020.

France 24. 2020. “Is bat soup a delicacy in China? We debunk a rumour on the origin of the virus,” (2020). The Observers, France 24, February 3. Accessed on 1 July, 2020.

Friedman, D. 2020. “Not Even the Head of a National Asian American GOP Group Is Okay With Trump Saying ‘Chinese Virus,’” Mother Jones, March 30. Accessed on 10 May, 2020.

General, R. 2020. “North Carolina Volleyball Club Director Sparks Outrage With ‘Don’t Eat the Bat’ Instagram Post,” NextShark, April 10. Accessed on 10 April, 2020.

General, R. 2020. “UCSC PhD Student Goes on Racist Rant Against Chinese People on Facebook,” NextShark, April 2. Accessed on 1 July, 2020.

General, R. 2020. “Racist and Xenophobic Flyers Target Asian Students at the University of Delaware”. NextShark, June 19. Accessed on 1 July, 2020.

Holland, A. T., & Palaniappan, L. P. 2012. “Problems with the collection and interpretation of Asian-American health data: omission, aggregation, and extrapolation.” Annals of Epidemiology, 22(6), 397–405. June 22. Accessed on 20 July, 2020.

Human Rights Watch. 2020. “COVID-19 Fueling Anti-Asian Racism and Xenophobia Worldwide.” May 12. Accessed on 15 May 2020.

Isenstadt, A. 2020. “GOP memo urges anti-China assault over coronavirus: The Senate Republican campaign arm distributed the 57-page strategy document to candidates,” Politico, April 24. Accessed on 1 July, 2020.

Ke, B. 2020. “Nebraska Company Allegedly Blames ‘Slanty Eyed C*nts’ for Shutdown Due to COVID-19,” NextShark, March 30. Accessed on 30 March, 2020.

Ke, B. 2020. “Drunk Man Has a Racist Meltdown Over Asian Family at California Restaurant,” NextShark, July 7. Accessed 20 July, 2020.

Kochhar, R. 2020. “Unemployment rate is higher than officially recorded, more so for women and certain other groups,” Pew Research Center: FactTank, June 30. Accessed on 30 June, 2020.

Liao, S. 2020. “Unemployment claims from Asian Americans have spiked 6,900% in New York. Here’s Why,” CNN, May 1. Accessed on 1 May, 2020.

Lin, K. 2020. Interview with Vivian G. Shaw on the AAPI COVID-19 Project, “Research at the intersections of COVID-19 crisis response,” The Harvard Crimson, April 30. Accessed 1, July, 2020.

Lu, W. 2020. “This is what it’s like to be an Asian Woman in the age of the Coronavirus,” Huffington Post, March 31. Accessed on 31 March, 2020.

Marist Poll. 2016. NBC/WSJ/Marist Poll Pennsylvania, July. Accessed 20 July, 2020.

Next Shark Incident Report form.

Peavey, A. 2020. “Documenting the Toll of the Coronavirus on New York City’s Chinatown,” PRI, The World, April 16. Accessed 20 July, 2020.

Peng, S. 2020. “Smashed windows and racist graffiti: vandals target Asian Americans amid coronavirus,” NBC News, April 10. Accessed on 10 April, 2020.

Randall. 2020. “Knife attack on father and sons labeled a hate crime,” AsAm News, March 31. Accessed on 31 March, 2020.

Ruiz, G., Horowitz, J.M., and Tamir, C. 2020. “Many Black and Asian Americans say they have experienced discrimination amid the COVID-19 outbreak,” Pew Research Center: Social & Demographic Trends, July 1. Accessed 1 July, 2020.

Samson, C. 2020. “Homeless Asian grandma in tears after getting spit on, cursed at asking for help in NYC,” Next Shark, March 26. Accessed on 26 March, 2020.

Samson, C. 2020. “‘You’re the virus’: couple allegedly threaten to kick fashion designer and her dogs in NYC,” Next Shark, March 30. Accessed on 31 March, 2020.

Sanders, L. 2020. “Biden leads Trump by 9 points in latest Economist/YouGov trial heat,” YouGov, July 16. Accessed 20 July 2020.

Smith, A. 2013. “Why Pew internet does not regularly report statistics for Asian Americans and their technology use,” Pew Research Center: Internet and Technology, March 29. Accessed 1 April, 2020.

Wallace, J. 2020. “‘China poisoned our people,’ says campaign ad,” Houston Chronicle, April 2. Accessed on 1 July, 2020.

Winfrey, K. 2020. “Central Indiana man says worker kicked him out of gas station because he’s Asian,” Wishtv, March 31. Accessed on 31 March, 2020.