Abstract: Taiwan was the first country to anticipate the threat of COVID-19, to send a medical team to investigate the initial outbreak in China, and to implement a comprehensive and successful public health response that avoided repeated infections or catastrophic lockdowns. Counter-intuitively, Taiwan’s success was achieved in part due to its exclusion from international bodies such as the World Health Organization, which led it to adopt a highly vigilant approach to health threats, especially those that emerge in China, whose irredentist claims impinge on Taiwan’s participation in the international community and constitute an existential military threat. Taiwan’s response to COVID-19 was recast by its diplomatic representatives into “The Taiwan Model”, a formulation used to pursue increased international recognition and participation.

Introduction

An “unexplained viral pneumonia” was first reported in Wuhan, China on December 31, 2019. Taiwan’s authorities, accustomed to paying close attention to threats from China, anticipated the possibility of infection and implemented a plan to contain it. After the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 epidemic spiraled out of control in Wuhan, China’s central government locked down the country after the disease had already begun to spread abroad. With most of the world locking down or suffering catastrophic losses due to the contagion that was later named COVID-19, Taiwan stood alone as an economically developed and democratically governed country that anticipated a health crisis and calmly contained the virus—with only 55 confirmed cases of local transmission and seven deaths as of July 2020, according to its Central Epidemic Command Center (CECC). Astonishingly, the contested state of Taiwan—recognized (formally as the Republic of China) by only 15 other countries and marginalized in international organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO)—emerged in many ways as the most normal country in the world

Taiwan’s success owed to past experience with SARS, extreme wariness of China (Leonard, 2020; Schubert, 2020), and a highly responsive public health administration coupled with universal health coverage, designed in part based on the counter-example of the US’s uneven and expensive system (Scott, 2020). An additional counter-intuitive factor, acknowledged even by Taiwanese medical authorities, may have been Taiwan’s exclusion from direct participation in the WHO, which led leaders to take a highly precautionary approach (Lin et al., 2020; Watt, 2020).

Yet, even before the outbreak of COVID-19, Taiwan had already been caught within a new round of tension and uncertainty between China, which claims its territory, and the US, with which it has a complicated relationship as guarantor of security and constrainer of sovereignty. At a different conjuncture, such an event might have engendered greater efforts towards regional if not national collaboration. It unfolded instead in a time and region rattled by talk of a new “Cold War”, with Hong Kong activist Joshua Wong figuring his city as a 21st century Berlin. Its liberation, argued Taiwanese sociologist Wu Jieh-min, required a US guarantee of Taiwan’s defense as the front line of democracy (Wu, 2020).

As the disease invoked a global state of exception, the exceptional state of Taiwan crafted a diplomatic campaign to expand its international space. Taiwan’s officials used its successful public health management to enhance the national image, expand space for international participation, and assert Taiwan’s sovereignty and distinction from China. The country’s public health approach, which included inbound travel bans, wide mask coverage, and contact tracing, was also presented, perhaps improbably, as a replicable approach for other countries to follow. This diplomatic campaign included designing and promoting the so-called “Taiwan Model” of health governance, and coining and circulating two slogans: #TaiwanCanHelp, and #HealthForAll.

To understand Taiwan’s public health governance and the diplomatic campaign it precipitated, it is necessary first to take a brief trip back in time to consider how the response to SARS (Sudden Acute Respiratory Syndrome), a disease caused by an earlier novel human coronavirus, set the stage for “The Taiwan Model”.

Taiwan and the World Health Organization: From SARS to SARS-CoV-2

SARS, caused by deadlier but less infectious coronavirus, hopped from an animal to a human in China in 2002 and then travelled to a Taiwan that was poorly prepared to receive it. Initial suppression of reports about the disease in China exacerbated the severity of the outbreak there and abroad. Taiwan’s crisis was worsened by the slow and politically-constrained response of the WHO, which did not send support until 50 days after Taiwan’s call for help, and only after the PRC gave permission. This episode marked the first time that representatives of a UN-affiliated agency officially visited the island since the 1971 UN General Assembly decision to expel the “representatives of Chiang Kai-shek”, which inaugurated Taiwan’s isolation from the international diplomatic community (Chen, 2018).

After 8096 reported cases and 774 casualties, SARS was contained globally in less than one year through aggressive quarantining and contact tracing of infected patients. Despite the tragedy of individual deaths, and the severe damage to affected economies, the rapid containment was hailed by many as a triumph of global health governance. Still, SARS accelerated an already-ongoing reorganization of global health governance designed to address the risk of emerging infectious disease. In particular, the WHA sped up its revisions to its International Health Regulations (IHR), which are the only legally-binding international treaty on global health governance. However, the IHR, as an international treaty structured through UN mechanisms, can only be ratified by UN member states, which made Taiwan ineligible to sign (Fidler, 2004).

For Taiwan, which suffered 73 deaths, the third highest number after China and Canada, SARS was a tragedy, but also a lesson to better prepare for future health threats, knowing they may be multiplied by diplomatic isolation (Lin et al., 2020). To address this, Taiwan continued its campaign to join the World Health Association (WHA), the UN representative body that governs the WHO.

During negotiations over the IHR revision, Taiwan’s diplomatic allies supported the inclusion of a clause for “universal application”, which could potentially include Taiwan. At the next session, PRC representatives responded by declaring that the new IHR applied to all of “Chinese territory”, including Taiwan, and signed a confidential Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the WHO Secretariat to enforce its claim. The MOU, which was later leaked, stipulated that Taiwan should not be allowed to participate under the name of “Taiwan” or “ROC”, that its invitee list must be approved in advance by the PRC, and that all communications between the WHO and Taiwan must be conducted through contacts in China. For the next several years, Taiwanese health authorities chose instead to conduct most communications with the WHO through their longtime contacts at the US Centers for Disease Control.

In 2008, Taiwan received a limited welcome into the WHO following the election of President Ma Ying-Jeou, who had pursued closer economic and political ties with China. In January 2009, with the assent of the PRC, WHO invited Taiwan to establish a direct point of contact through IHR mechanisms to exchange information on health emergencies. It also allowed Taiwanese officials to log in to the WHO’s Event Information Site, where it could examine advisories shared between member states. Furthermore, WHO promised that it would send experts to Taiwan in the event of a health emergency. A few months later, with only a few weeks’ notice, the WHO Director-General invited Taiwan, as “Chinese Taipei”, to join the meeting of the WHA as a non-voting observer, which did allow its representatives to make personal contacts share information. After Ma’s Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), which advocates for the “unification” of Taiwan and China, lost the presidency to Tsai Ing-wen of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in 2016, Taiwan was no longer invited to the meetings of the WHA. No explanation was provided by the WHA or WHO (Chen, 2018).

The WHO’s changing posture towards Taiwan was shaped not only by its the MOU with the PRC, but also by China’s increasingly sophisticated coordination of WHA member-state votes. Such coordination included cultivating relationships with candidates whom the PRC supported for Director-General, including Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus of Ethiopia, confirmed in 2017 (Buryani, 2020). Dr. Tedros went on to sign an MOU in support of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, and traveled to Beijing to praise Xi’s proposal to pave a “medical silk road” that same year (Murphy, 2018).

“Wuhan Pneumonia”

On 31 December 2019, the same day Wuhan police announced that they were investigating doctors for spreading unsubstantiated rumors and “disturbing social order”, municipal health officials released information about a viral pneumonia that had infected visitors to a seafood market. The statement said that there was no clear evidence of human-to-human transmission, and claimed that, “The disease is preventable and controllable”. Wuhan police detained more doctors for sharing warnings in private Wechat groups, as scientists in Wuhan, Shanghai and Beijing identified the pathogen and sequenced its genome. Early reports suggested that, like SARS, the disease may have originated in horseshoe bats, before jumping to humans through an intermediate species, possibly pangolins.

Chinese officials did promptly report the disease through its WHO IHR point of contact but claimed for weeks that the disease was not contagious between humans, a claim that was repeated by WHO officials through mid-January. Although Xi Jinping later announced that he initiated an inquiry and response team in the Politburo as early as January 7, the city’s health commission reported zero new cases and continued to maintain that there was no evidence of human-to-human transmission or infected medical personnel between January 12 and 18. This period coincided with the annual People’s Congress of the municipal branch of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and a massive, 40,000-family public banquet to celebrate the Lunar New Year. These events went ahead as scheduled despite official knowledge that the pneumonia may be contagious (Buckley and Myers, 2020).

Official denial ended when China’s most-famous epidemiologist, Zhong Nanshan, who helped lead the response to SARS, visited Wuhan and on January 20 announced during an interview on state television that there was no doubt of human-to-human transmission. Wuhan officials banned the entrance of tour groups and locked the entire city down on the morning of January 23, undoubtedly with the assent of Beijing (Buckley and Myers, 2020). Travelers who had already left Wuhan and Hubei province continued moving across China as other provinces began implementing lockdowns and the central government formulated a more comprehensive response. International travel continued to depart from elsewhere in the country, until outbound tour groups were banned, and various countries shut their land or air borders to arrivals from China.

Although WHO officials consistently denounced border closures, tourists and travelers were among the first targets for preventive measures against the spread of the virus, first in China and then internationally. Hotels across China refused to house travelers from Hubei, until the central government coordinated a list of venues that would take them in and even offered to repatriate ones who had already left the country. As for other countries, many simply banned arrivals from China and a growing list of other sending regions, sometimes including Taiwan, before formulating other public health responses.

Taiwan’s Public Health Response

The morning of December 31, the deputy Director of Taiwan’s Center for Disease Control (CDC), awoke to a text message from his colleagues in the media monitoring unit. The message contained laboratory reports and warnings from Wuhan doctors about an unusual viral pneumonia that had been circulating for days. The reports had been deleted within China but preserved on PPT, a freewheeling Taiwanese internet site. The same day, Taiwan officials emailed their IHR point of contact to ask for more information about the new disease. The email noted that patients were being isolated for treatment, which implied concern about the possibility of human-to-human transmission. The email was never answered. “We were not able to get satisfactory answers either from the WHO or from the CDC, so and we got nervous as and we started doing our own preparation,” said Foreign Minister Joseph Wu (Watt, 2020). Taiwanese medical staff began performing health checks on inbound flights from Wuhan the same night. Still concerned about what they were hearing through their contacts within China, Taiwanese officials sent a medical team to the city to investigate between 13 and 15 January (Watt, 2020). Based on the team’s collection of confused and alarming responses about infection clusters reported by interviewed doctors, Taiwan’s CDC listed the virus as a highly communicable disease on 15 January.

Before Chinese authorities or the WHO publicly confirmed that the virus could spread from human to human, Taiwan had already set up a Central Epidemics Command Center, headed by the minister of health and welfare, to coordinate response efforts by various agencies, including the ministries of transportation, economics, labor, and education and the Environmental Protection Administration. The legal basis for this had been established through post-SARS legislation.

Anticipating a possible shortage of protective gear, authorities also banned mask exports, ramped up domestic mask production, and implemented a rationed mask distribution system with the help of computer scientist Audrey Tang, a social movement veteran who had earlier been tapped by the Tsai administration as “Digital Minister” to spearhead e-governance and civic technology initiatives (Chang, 2020). To identify suspected cases and facilitate isolation and contact tracing, national health insurance and immigration databases were integrated. Mobile phone network monitoring systems were incorporated to help enforce home quarantine (Wang et al., 2020). Taiwan was praised by medical scholars for its “astounding” success in conducting robust contact tracing, testing, and reporting of the results of its first 100 cases to the international medical community (Steinbrook, 2020).

Technocratic decision-making and a high level of public compliance primed by past experiences with SARS maintained Taiwanese life at a nearly normal pace. Apart from a precautionary two-week extension of the New Year holiday, schools, cinemas, and bars remained open. Although this was done without invoking emergency decrees, and in accordance with constitutional court interpretations of post-SARS legislation, legal scholars and some critics raised concerns about the extent of expanded government powers. These at least were set to expire with the end of the epidemic and were likely tempered by reluctance to invoke extreme measures that might evoke grim memories of the past authoritarian KMT regime (Lin et al., 2020).

As the domestic public health response was implemented, national sentiment grew inflamed by a fraught evacuation process for Taiwanese people trapped in a locked-down Wuhan. While several other countries smoothly evacuated their nationals from the city, Taiwan’s efforts to transport roughly 500 citizens were stymied by their unusual diplomatic position. As with many arrangements between Taiwan and China, much of the negotiation took place not between formal government bodies, but through informal business and political party channels that included KMT officials with CCP ties.

For the first charter flight in February, operated by Taiwan’s flag carrier—the confusingly-named China Airlines—Taiwan’s Mainland Affairs Council prepared a passenger list that prioritized short-term visitors to Wuhan and other people who lacked nearby support. The agency also insisted on preventative measures, including pre-boarding health checks and provision of protective gear for passengers. While pre-approved passengers readied to board, Chinese authorities did not issue the protective gear, saying it was unnecessary, and attempted to include an additional 30 people who had not been cleared for arrival in Taiwan. Furor erupted when Taiwan media reported that three of the passengers that arrived at Taoyuan Airport were not included on the pre-approved list. This included a passenger who was detected with a fever upon arrival and later diagnosed with COVID-19 (Lee et al., 2020; Yang and Hetherington, 2020). It also turned out that many of the passengers were PRC nationals married to Taiwanese businessmen, renewing older controversies about the entry and residence rights of such spouses and their children (Friedman, 2015). It turned out that a Taiwanese businessman, Hsu Cheng-wen, who led a “Parents Association” for Taiwanese families based in China, coordinated some of the communication with Chinese officials. Hsu, a member of both the KMT Central Committee and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, a CCP body, went on local media to criticize DPP officials for “playing politics” over the evacuation. He was later suspended from his KMT position after a public backlash (S Lin, 2020).

While China scrambled to ramp up its own mask production, and party-state agents and concerned citizens alike purchased large supplies overseas to ship home, Taiwan’s early decision to ban mask exports was criticized as “heartless” both by PRC media outlets and KMT officials. Taiwan’s later agreement to donate masks to the US in exchange for other protective gear, which came after the PRC reported it had turned the corner with disease containment, received a further round of blistering criticism. “The DPP authority’s hatred of China and flattery of the US is more poisonous than the virus itself” declared a headline on 19 March in the PRC outlet, Xinhua (Minjindang dangju ‘chou Zhong mei Mei’ bi bingdu hai du民进党当局“仇中媚美” 比病毒更毒). Despite its expression of concern about cross-Strait sentiment, the article did not consider how the many People’s Liberation Army air force and naval exercises that took place during the same period, including warship cruises and fighter jet fly-bys directed towards Taiwan’s territory, might be perceived in Taiwan. These were likely intended to demonstrate that the PRC could still pose a credible military threat even while it was under lockdown (Brown and Churchman, 2020).

In the meantime, Taiwanese health officials collaborated with Stanford University researchers to develop a new protocol for international travel, saying they hoped it might be adopted elsewhere. By testing ways to safely shorten quarantine for pre-tested travelers, “We hope to develop a safe travel protocol which we could use to gradually restart some travel links with like-minded countries,” said Chen Chi-mai, Taiwan’s deputy premier. A similar collaboration with China, however, was off the table. As Vice President Chen Chien-jen, the celebrated epidemiologist who had led the SARS response, told the Financial Times, “Until today, we don’t even have data on how many people have been tested in China. So we have to be more cautious” (Hille, 2020). Needless to say, these officials did not view China as a “like-minded country”.

Steady leadership and clear messaging earned Taiwan’s president an astonishingly high and consistent approval rating of over 70%, likely the most sustained level of public support ever polled in Taiwan (Batto, 2020). Health officials held daily briefings which were used to share not only information about the epidemic, but also other messages about national values, as well as to promote places of pride. In April, following news reports of a boy who complained that only pink masks were available, which made him fear that he might be bullied, all of the officials at that day’s briefing, including male ministers, wore pink masks to show that color needn’t be gendered. As daily cases diminished, popular fruit including guavas and watermelons were artfully arrayed on stage to count the number of days without new cases, while also promoting Taiwanese agricultural products. The tourism industry was hit hard, although some compensation for the sector was included in a large subsidy package (Chang, 2020). At the Sun Moon Lake Ita Thao pier, the frog sculpture used to measure the water level wore a Hakka-style floral print face mask and stood behind placards that announced the growing number of days without infections. No Chinese tourists were there to see it.

“Taipei and Environs” vs “The Taiwan Model”

Taiwan made an early decision to block inbound flights from Hubei and later all inbound travel from China, a move followed later by many other countries, including the US. Such decisions flew in the face of WHO officials’ discouragement of travel blocks and praise for China’s response (Associated Press, 2020). Several other countries that reported serious outbreaks, including Italy, South Korea, and Iran, were later added to Taiwan’s ban list. By late March, as global caseloads rose, all inbound arrivals were barred except for residents, citizens, and exceptional cases.

Although the WHO advocated against flight bans and border closures, a number of countries began to implement them anyway, and seemed to choose sites based on WHO regional designations, rather than a risk calculus. Italy banned all flights from China and Taiwan, evidently following the representation of Taiwan as a part of China within the International Civil Aviation Organization, another UN-affiliate agency. Vietnam and the Philippines also initially blocked flights from Taiwan, in at least one case temporarily stranding already-boarded passengers on the tarmac, until officials reversed their positions and resumed flights following complaints from Taiwan’s foreign ministry (Lema and Blanchard, 2020).

The WHO’s seemingly slow response to a growing global crisis, and its consistent praise for PRC leaders, called the political allegiances of the organization into question. WHO officials publicly acknowledged human-to-human transmission of the virus only on January 21, well after Taiwan’s CECC had made its own determination. The WHO went on to classify the disease as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern on 30 January. During a media briefing on 11 March, the WHO Director-General said it “can be characterized as a pandemic”, itself a term which is ambiguously defined by WHO’s own regulations. In the meantime, a number of countries less vigilant than Taiwan had already failed to craft a comprehensive response.

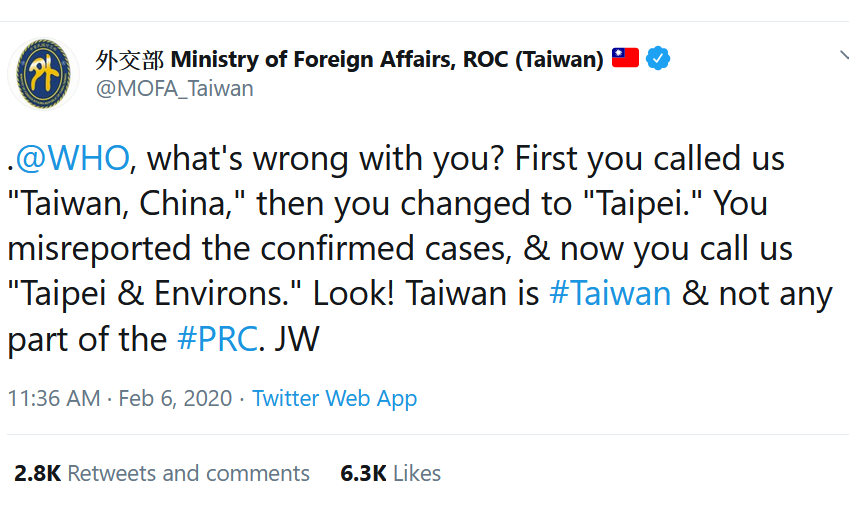

The contrast between the WHO’s slow response and Taiwan’s pro-active measures earned Taiwan the most positive international press it had received in years. At the same time, Taiwan found its own figures grouped further with those of China under a confusing set of changing designations in the WHO Daily Situation Report, which was posted on the organization’s website and narrated in its briefings. The Situation Report tabulated cases by “Countries, territories, or areas”, and listed Taiwan’s reported case figures under PRC provinces, designating it, variously, as “Taiwan, China” (starting with the 2nd report on 21 January), “Taipei Municipality” (from 23 January), “Taipei” (from 25 January), and finally, the never-before-seen “Taipei and Environs” (from 5 February). In response, Foreign Minister Joseph Wu lambasted the WHO on Twitter. “What’s wrong with you? First you called us ‘Taiwan, China,’ then you changed to ‘Taipei.’ You misreported the confirmed cases, & now you call us ‘Taipei & Environs.’ Look! Taiwan is #Taiwan & not any part of the #PRC.”

|

Figure 1. Taiwan Minister of Foreign Affairs Joseph Wu response to WHO. 6 February 2020. |

Taiwan’s bizarre diplomatic plight was demonstrated during an awkward video interview with a senior WHO official, Dr. Bruce Aylward, conducted by a journalist from Hong Kong public broadcaster RTHK (Chan, 2020). After the journalist asked him if Taiwan might be allowed to join the WHO, Aylward blinked several times and claimed that he could not hear the question. After the journalist offered to repeat the question, he said “No, that’s OK, let’s move on to another question then,” before dropping the call without explanation. After the journalist called back and said she would like to talk more about Taiwan’s epidemic response, Aylward answered, “Well, we’ve already talked about China. And when you look across all the different areas of China, they’ve actually all done quite a good job.” He then thanked the interviewer and promptly ended the call. After the video went viral, Aylward’s profile vanished from the WHO website. WHO spokespeople later clarified in a press release that Taiwan’s membership is up to member states and not staff, and asserted that the organization is working closely with Taiwanese health experts, a claim refuted by Taiwan officials (Blanchard, 2020; Davidson, 2020).

The apparent suppression of Taiwan’s international participation heightened media attention and amplified a pushback from prominent figures in technology, public health, and entertainment, many of whom characterized it as a country. Bill Gates said in an interview, “I don’t think any country has a perfect record. Taiwan comes close. They really were talking about it, and it’s unfortunate they weren’t part of the WHO to really get those warnings paid attention to” (Financial Times, 2020). This was a striking position to take for someone who heads a foundation that is one of the WHO’s largest financial donors. In an ironic twist, singer Barbra Streisand, for whom the Streisand Effect was named—for making information more widely known by trying to suppress it—joined the fray. She noted in a tweet: “Taiwan, despite being just 100 miles from mainland China with regular flights to and from Wuhan, has successfully staved off the worst of the coronavirus pandemic. The country has so far seen five deaths and just under 350 confirmed cases, and most schools and businesses remain open” (Shattuck, 2020).

Building on such earned press, the so-called “Taiwan Model” was coined by diplomats not merely to denote an epidemic response, but deployed as part of a wide-ranging strategy for increasing Taiwan’s international space. MOFA added an English-language section to its website, “The Taiwan Model for Combatting COVID-19”, which featured a large banner with the slogans, “Taiwan Can Help” and “Health for All,” and the following account:

|

When a SARS-like virus, later named as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), first appeared in China in late 2019, it was predicted that, other than China, Taiwan would be one of the most affected countries, given its geographic proximity to and close people-to-people exchanges with China. Yet even as the disease continues to spread around the globe, Taiwan has been able to contain the pandemic and minimize its impact on people’s daily lives. The transparency and honesty with which Taiwan has implemented prevention measures is a democratic model of excellence in fighting disease…The materials found here also help explain the different aspects of Taiwan’s epidemic prevention work, and how Taiwan is helping the international community. |

As of May 2020, the site specified the “measures” and “results” of the model: “Taiwan’s comprehensive national health insurance system and our experience of fighting the SARS epidemic; A whole-of-government system coordinating interagency resources and manpower—battling against COVID-19 through unified, decisive efforts; Advance preparations and early response to COVID-19 pandemic; Public-private partnerships to contain COVID-19; Tackling COVID-19 with the help of big data and AI; [and] Open and transparent information promoting social stability”. Each element linked to an explanatory document watermarked by the “Taiwan Can Help” and “Health for All” slogans.

The same slogans were circulated by Taiwan’s formal and informal diplomatic allies in a series of ads, social media posts, and even a skywriting message spotted over the Chinese embassy in Canberra, some of which were state-supported, and some of which were crowdfunded by Taiwanese citizens. The US State Department officials promoted a Twitter campaign with the hashtags #TweetforTaiwan and #TaiwanModel. The #TaiwanCanHelp campaign included donations of masks to a variety of countries, including the US, where White House officials donned “Made in Taiwan” masks during press conferences (McLaughlin, 2020).

|

Figure 2. MOFA Instagram announces a donation of 300,000 masks to Indonesia. 15 May 2020. |

Even as US federal and state governments clashed over crisis coordination, and congressional Democrats and Republicans fought over financial bailout packages, Taiwan represented a rare bipartisan cause for agreement. The US Congress and Senate unanimously passed the Taiwan Allies International Protection and Enhancement Initiative (TAIPEI) Act, which was signed into law on March 26 and called for the US to support Taiwan’s increased participation in international institutions (J Lin, 2020). Beyond the US, the campaign included unprecedented expressions of support from leaders in Canada, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, and much of Europe. Literally mobilizing their “model”, MOFA officials also allowed nationals of several other countries to board an evacuation flight from locked-down Lima to Miami in late March, “out of humanitarian concern, and to show that ‘Taiwan can help’” (Lu, 2020). A long-running effort to rebrand the anachronistically-named national flag-carrier, China Airlines, whose airplanes were busy moving the “Made in Taiwan” model around, also got a renewed push, even as global news outlets continued to misuse images of China Airlines’ airplanes in stories about China’s air carriers.

The campaign was directed towards lobbying to expand the scope of participation in the WHA. Taiwan’s formal diplomatic allies were expected to submit proposals for Taiwan’s admission at the annual meeting on May 19. Several days before, when asked at a press conference about a PRC foreign affairs official’s demand that Taiwan accept a “One China” premise in order to participate in the WHA, Taiwan’s Minister of Health and Welfare, Chen Shih-chung, flatly stated, “We have no way to accept something that does not exist” (Wintour, 2020). With a successful vote looking unlikely, and Taiwan’s allies expressing concern for their own public health crises, diplomats withdrew the motion.

Even as Taiwan’s policy makers looked towards eventual WHO membership as a stepping-stone to international normalization, their way forward looked even more uncertain when US President Trump announced that he would withdraw the US from the international body. Apparently seeking to deflect from his administration’s catastrophic response to COVID-19, Trump complained that China’s crisis response was unfairly praised by WHO leaders. He implied that the WHO was under undue Chinese political influence, even if the US remained by far the WHO’s largest funder (Associated Press, 2020).

In the very same speech, Trump indicated that the US would no longer recognize Hong Kong’s separate customs status, as a response to the PRC’s announcement of a new national security law for Hong Kong. The bill was denounced in the US and in Taiwan—even by KMT leaders—as the effective end of Hong Kong’s promised autonomy under the “One Country, Two Systems” framework. While some in Taiwan celebrated the strong stance taken by the US against the PRC, Taiwan’s geopolitical position looked all the more tenuous, especially given that the Tsai administration had just promised to help resettle Hong Kongers who might face political persecution under the new national security law.

Conclusion: The Absurdity of Taiwan’s Exceptionality

The WHO’s treatment of Taiwan would likely have shocked its first Director-General, Brock Chisholm, who, like Bruce Aylward, hailed from Canada. A pioneering globalist, Chisholm advocated the replacement of national citizenship with world citizenship and denounced the ROC international representation of China as “an absurdity which is outstanding even in this era of absurdities” (Farley 2008, 90). China’s contemporary claims to represent Taiwan are no less absurd, but by now, Chisholm’s calls to “sacrifice much of our own national sovereignties” for the sake of world health sound quaint, urgent, and unthinkable all at once.

Cast against the pandemic, the geopolitical absurdity of Taiwan’s exclusion could be posed as another pathological condition plaguing a world in which, as put by Hannah Arendt, “the right to have rights, or the right of every individual to belong to humanity, should be guaranteed by humanity itself”. However, given the limited efficacy of international law, the practice of human rights effectively “operates in terms of reciprocal agreements and treaties between sovereign states”, as Arendt presciently argued after the 1948 international adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1958: 298). As such, the rejection of Taiwan’s participation signifies a persistent disavowal of the United Nations’ constitutive promise of universal application.

Many commentators argue that the implications of Taiwan’s exclusion from international bodies extend beyond the human rights of its 24 million citizens. Refusing Taiwan direct access to the WHO constitutes a clear and present danger to global public health, suggested The Economist, among other prominent outlets that acknowledged its world-leading response and bemoaned the fact that its vigilance was unfollowed (Banyan, 2020; Leonard, 2020). Taiwan, of course, may have come out all the healthier for being on its own. However, in this otherwise unmitigated moment of triumph, its polity still navigating through a brewing conflict between the US and China, the archipelago appeared as precarious and vital as ever.

References

Arendt H., (1958). The Origins of Totalitarianism. 2nd ed. Meridian Books.

Associated Press, (2020). China delayed releasing coronavirus info , frustrating WHO. Associated Press, 2nd June.

Banyan, (2020). Let Taiwan into the World Health Organisation. The Economist.

Batto, N., (2020). Public opinion in May 2020. Frozen Garlic. (accessed 24 June 2020).

Blanchard, B., (2020). WHO says following Taiwan virus response closely, after complaints. Reuters, 29th March.

Brown, D.G. and Churchman, K., (2020). China-Taiwan Relations: Coronavirus Embitters Cross-Strait Relations. Comparative Connections: A Triannual E-Journal of Bilateral Relationsin the Indo-Pacific 22(1): 73–82.

Buckley, C. and Myers, S.L., (2020). As New Coronavirus Spread , Chinaʼs Old Habits Delayed Fight. New York Times, 1st February.

Buryani, S., (2020). The WHO v coronavirus: why it can’t handle the pandemic. The Guardian, 10th April.

Chan, W (2020). The WHO Ignores Taiwan: The World Pays the Price. The Nation.

Chang, W. (2020). Taiwan’s fight against COVID-19: Constitutionalism, laws, and the global pandemic. Verfassungsblog. (accessed 27 March 2020).

Chen, P.K., (2018) Universal participation without Taiwan? A study of Taiwan’s participation in the global health governance sponsored by the world health organization. Asia-Pacific Security Challenges: 263–281.

Davidson, H., (2020). Senior WHO adviser appears to dodge question on Taiwan’s Covid-19 response. The Guardian, 30th March.

Fidler, D.P., (2004). SARS, Governance and the Globalization of Disease. Palgrave Macmillan.

Financial Times, (2020). Bill Gates speaks to the FT about the global fight against coronavirus. Financial Times, 9th April.

Friedman, S.L., (2015). Exceptional States: Chinese immigrants and Taiwanese sovereignty. University of California Press.

Hille, K., (2020). Taiwan trial offers hope for restoring international travel. Financial Times, 18th May.

Lee, I., Wu, L. and Chung, L., (2020). Wuhan flight passenger list rumors ignite furor. Taipei Times, 6th February.

Lema, K. and Blanchard, B., (2020) Taiwan urges Philippines to lift ban on its citizens over coronavirus fears. Reuters, 11th February.

Leonard, A., (2020). Taiwan Is Beating the Coronavirus. Can the US Do the Same? Wired.

Lin C-F, Wu C-H and Wu C-F, (2020). Reimagining the Administrative State in Times of Global Health Crisis: An Anatomy of Taiwan’s Regulatory Actions in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic. European Journal of Risk Regulation: 1–17.

Lin, J., (2020). Does the TAIPEI Act help a marginalised Taiwan? Taiwan Insight.

Lin, S., (2020). Virus Outbreak: Evacuation flights to be set by Taipei and Beijing. Taipei Times, 7th February.

Lu, Y., (2020). Virus Outbreak: Taiwan shares evacuation. Taipei Times, 30th March.

McLaughlin, T., (2020). Is This Taiwan’s Moment? The Atlantic.

Murphy, F., (2018) Rise of a new superpower: Health and China’s global trade ambitions. BMJ 360(February): 1–4.

Schubert, G., (2020). Taiwan has done exceptionally well in fighting COVID-19 – but needs an ‘exit strategy’ as well. CommonWealth.

Scott, D. (2020), Taiwan’s single-payer success story — and its lessons for America. Vox, 13th January.

Shattuck, T.J., (2020). The Streisand Effect gets geopolitical: China’s (unintended) amplification of Taiwan. Foreign Policy Research Institute.

Steinbrook, R., (2020). Contact Tracing, Testing, and Control of COVID-19—Learning From Taiwan. JAMA Internal Medicine.

Wang CJ, Ng CY and Brook RH, (2020). Response to COVID-19 in Taiwan: Big Data Analytics, New Technology, and Proactive Testing. JAMA Internal Medicine 323(14): 1341–1342.

Watt, L., (2020). Taiwan Says It Tried to Warn the World About Coronavirus. Here’s What It Really Knew and When. Time, 19th May.

Wintour, P., (2020). Taiwan must accept Chinese status to attend WHO, says Beijing. The Guardian, 15th May.

Wu, J., (2020). Taiwan’s response to Hong Kong’s Berlin Crisis 香港「柏林危機」下的台灣對策. The Reporter.

Yang, C. and Hetherington, W., (2020). Virus Outbreak: China meddles with evacuation flights. Taipei Times, 12th March.