Abstract: There is a longstanding and fundamental asymmetry in level of mutual understanding between the US and China. Chinese citizens are avid consumers of American media and cultural products, whereas most Americans are woefully unfamiliar with even the basics of Chinese history and culture. This asymmetry has resulted in a situation where the US is in danger of misinterpreting or misunderstanding Chinese motivations in bilateral relations, particularly in times of crisis. This paper recounts how the Covid-19 epidemic of 2020 exacerbated existing tensions between the US and China, and how these escalations in state-to-state conflict were in large part due to America’s information deficit with the PRC.

Introduction

There is a longstanding and fundamental asymmetry in the level of mutual understanding between the US and China. John Holden, a seasoned China hand formerly with the National Committee on US-China Relations (NCUSCR), has characterized this difference in the following way: The problem Americans have in understanding China is a lack of information; the usual channels of information are tightly controlled, and much about the country and its governance seems opaque and mysterious. Chinese analysts of the US are faced with the opposite problem; there is such an overabundance of information about US society, politics and government that they have difficulty sorting it out and making sense of the cacophony (J. Holden, personal communication, 1998).

Holden made these observations before the expansion of Internet access in China, but despite the information explosion brought by the digital revolution, this fundamental asymmetry between the two countries remains. And this is true not only of the academies and think tanks of China and the US, it is also common among average citizens of both countries. Across most classes and demographics groups, the Chinese know more about us than we know about them. This is a problem, because the US-China relationship, as vital as it is to the global economy and security, is spiraling into increasingly heated episodes of misunderstanding and conflict. The international Covid-19 crisis has exacerbated existing bilateral tensions, many of which are the result of longstanding and unresolved historical and cultural schisms. It seems clear that many of the recent diplomatic and cross-cultural missteps on the part of the US are due to a lack of knowledge of Chinese culture and history on the part of not only the political leadership, but of the American media and public at large. A stable and productive bilateral relationship requires contact and compromise at all levels, and a deeper understanding of – though not necessarily agreement with – the other side’s position. Very often the sticking points in the relationship are due to the basic asymmetry of information flow: We lack an adequate understanding of them, whereas often they know us all too well.

Possible sources of the asymmetry

There are several overlapping reasons for this asymmetry, some structural, some cultural, and some historical. Because of its preeminence in the world economy and its soft power influence, the US has been an outsized presence in world discourse. China, as with other countries, has had to acclimate itself to the American style of global engagement, and absorb American cultural norms in order to fit in with the US-dominated world order. Since China’s reform period in the 1980s, Chinese people have been avid consumers of American popular media and students of the American way of life. The digital explosion of the late 1990s saw a massive influx of bootleg DVDs and CD-ROMs into the country, exposing generations of young Chinese people to Hollywood films and US TV programs. The rapid growth of the Chinese Internet in the 2000s resulted in an even greater influx of news, entertainment and information from US sources, and as the price of computers and digital devices fell, the average Chinese consumer had easy access to a great deal of the mainstream media output American produced.

It is well known that China’s Internet blocks many foreign websites, and much American media is inaccessible within the PRC. Yet, despite massive Internet censorship, China’s Great Firewall is actually somewhat porous. Censorship circumvention programs such as Virtual Private Networks (VPNs), while technically illegal, are still obtained by young Internet-savvy Chinese, affording many millions of people access to the blocked sites from the US and elsewhere. For example, the media platform Twitter, which is blocked in China, is said by the company to have 10 million active users within China (Ng 2016). In addition, the Chinese Internet has many “leaks” that allow restricted information to flow within the system, such as cutting and pasting blocked material, attaching files in email attachments, converting webpages to digital photo documents, and the informal sharing of digital files via USB drives.

Another source of informational asymmetry is the sheer number of Chinese nationals and students residing in the US for work or study. 2019 statistics put the number of Chinese students in the US studying for undergraduate and graduate degrees at about 370,000, and this number increases yearly (Statista 2019). Chinese students in the US are the source of a tremendous amount of information and insight about America that is informally communicated to parents and friends via email, telephone and social media, particularly the ubiquitous Chinese communications app, WeChat. The sheer amount of this quotidian messaging is incalculable, and it means that many average Chinese have a steady stream of first-hand accounts of American society and culture. Meanwhile the number of American students in China pales by comparison. After a jump in the number of China-bound US students around the 2008 Olympics, the total has declined to 11,000 in the 2017-18 school year, an insignificant fraction of the number of Chinese students in US schools (Feng 2020).

English education in China, as with most other countries, is a required part of basic education. Since Deng Xiaoping’s Reform and Opening period, China has made English an integral part of the college entrance exams, and the number of people studying English is estimated to be over 300 million, nearly the population of the United States (Tan 2015). The result is an enormous number of educated people who are able to directly surf English websites, read English books, and view English-language film and video media in the original language, without the aid of translation. Many young people with good English skills actually enjoy adding Chinese subtitles to American films and TV shows and distributing these translations online, thus increasing the number of their fellow citizens who are able to understand and appreciate such English-language media.

By contrast, a relatively small number of Americans are learning Chinese at either the secondary or tertiary level, and due to the relative late start such students have, they seldom reach the levels of listening comprehension and fluency in Mandarin that their counterparts in China attain in English. Thus, while hundreds of millions of Chinese can access English language information directly, far fewer Americans, even those with some Chinese ability, are able to view and absorb Chinese media, surf Chinese websites, or read Chinese news feeds.

There are also differences in the media control systems of China and the US that impact the extent of the informational asymmetry. Chinese film and television are as varied and rich as any other world media in terms of entertainment products, but news and political programming is tightly controlled. There is actually a wide spectrum of political orientation in China, but the full scope of public opinion is not fully represented due to censorship. There is no Chinese equivalent to the heated left-right political dialogues and town halls on American television. Chinese politicians and public figures do not argue policy in public, and politics is in general excluded from non-news programming; there is, in fact, a strict separation between entertainment and news. To the interested American netizen, this state of affairs effectively masks the true state of ideological diversity within the PRC and obscures a full picture of the pluralism that exists in the country.

US media, in contrast, is fully corporatized, profit driven, and ratings focused, resulting in a media environment where infotainment is the norm. News shows are produced as entertainment, and entertainment shows regularly showcase politics. (Note how the main staple of late-night TV comedians’ monologues is usually satirical attacks on the president.) Whereas politics and public policy in Chinese media is treated in a didactic and sober manner, in the US politics is played out as blood sport. Again, the challenge for interested Chinese observers of the American scene is to make some coherent sense of the rowdy and chaotic oversupply of information.

The result of the digital and Internet revolution in China is that Chinese citizens are afforded a front row seat to our domestic debates and culture wars. Information-savvy Chinese have not only studied our history, our politics and our language, they have also, in a virtual sense, spent time in our lecture halls and living rooms, overhearing our conversations, listening in on our arguments, and observing how we think about the rest of the world. But most of all, this means that Chinese have spent much time listening to Americans talk to other Americans about China. After countless hours of hearing presidents, politicians, academics, talk show hosts, news commentators and other public figures talking about their country, the average culturally aware Chinese person has a reasonably good grasp of the range of opinions in the US. By contrast, most Americans in general know little about China’s history and culture, and have spent virtually no time exploring China’s media world. The inevitable result is that Americans tend to know scarcely anything about China, and even less about what the Chinese think about America.

The asymmetry in the Covid-19 crisis

In late December when news of Covid-19 began to emerge in China, China-US relations were already strained to the breaking point. President Trump was in the midst of waging a protracted trade war and had surrounded himself with China ‘dragon slayers’ such as Peter Navarro, Michael Pillsbury and John Bolton. The US State Department had issued a string of criticisms of China for human rights abuses, such as the internment of up to a million Uighurs in ‘reeducation camps’ in Xinjiang province. There was much talk of the US and China being locked in a ‘Thucydides Trap,’ and the term ‘decoupling’ was already a buzzword in the mainstream press.

The animosity between the two countries was only exacerbated by the anti-China rhetoric streaming freely into Chinese cyberspace. In the first months of 2020, as China’s Covid-19 epidemic was gradually subdued and the US began to see its infection rates peak, China’s information environment was awash in videos and media clips from other countries, particularly the United States. In addition to official news from China’s highly centralized network of official state TV and Internet news outlets, China’s social media was also flooded with a tsunami of video and text information. Video clips from foreign news sources about China’s handling of the epidemic were reposted hundreds of millions of times a day, due to the enormous reach of combined social media platforms such as Sina’s Weibo (497 million users), Tencent’s WeChat (1.15 billion users) and Bytedance’s AI-powered news and entertainment aggregator Toutiao (200 million users) (IH Digital 2020).

Sampling the enormous amount of information on these sites provided Chinese netizens a panoramic overview of the foreign discourse concerning the virus. The constantly updated stream of clips and videos taken directly from American media outlets (with Chinese subtitles and often accompanied by blogger commentary) allowed Chinese social media users to listen in on America’s fractious domestic political commentary and talk show debates. As I scrolled through Toutiao’s infinite ribbon of media clips, I found that I could follow Trump’s daily Covid-19 task force press briefings, then watch comedians Stephen Colbert and Trevor Noah skewer the president for his rambling statements and constant gaffes. The wide spectrum of opinion, speculation, information and misinformation was all at the user’s fingertips. In quick succession, Chinese netizens could sample sane and sober comments from Kevin Rudd, former Australian Prime Minister, China hand and fluent Mandarin speaker, and then scroll downwards to hear wild coronavirus conspiracy theories from conservative talk show host Rush Limbaugh.

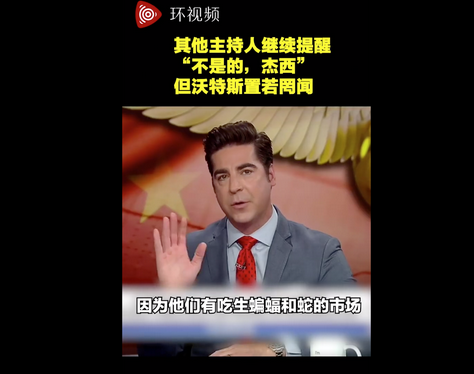

Given this mix of reasoned analysis and vociferous China bashing, it was usually the latter that garnered the most attention online. On March 2, 2020 Fox News aired a segment on “The Five” show, wherein the following exchange took place:

Jesse Watters (co-host of The Five): I ask the Chinese for a formal apology. This coronavirus originated in China, and I have not heard one word from the Chinese, a simple ‘I’m sorry’ would do. So [I’m] demanding a formal apology from the Chinese people.

Dana Perino (co-host of The Five): What if the outbreak had started here?

Watters: It didn’t start here, Dana, and I’ll tell you why it started in China. ‘Cause they have these markets where they’re eating raw bats and snakes…They are very hungry people. The Chinese communist government cannot feed the people. And they are desperate, this food is uncooked, it is unsafe. And that is why scientists believe that’s where it originated from.

The very next day this video clip, with captions in Chinese, was already going viral on China’s social media (Shao 2020). The following day Zhao Lijian, a spokesperson from China’s Foreign Ministry, called Watter’s remarks “ridiculous” and “laughable,” (You 2020). Outraged social media comments speculated whether the remarks represented the opinions of the US government or were only rogue opinions from an irresponsible talking head. This sort of media event, common during those weeks, is a reflection of the information asymmetry in question. An offhand crass remark in an American infotainment show was capable of triggering a diplomatic squabble that attracted the attention of the Chinese Foreign Ministry. While some potentially inflammatory anti-American remarks are also heard on Chinese media, such offending comments are seldom picked up by American news outlets and never find their way into the social media environment. The Chinese were highly attuned to American invective directed at them; the American media were largely oblivious to any Chinese vitriol spewed in their direction.

But it was not only the inflammatory language on American television shows that was amplified in the Chinese media space. On February 3, the Wall Street Journal published an editorial critical of China’s handling of the coronavirus outbreak, with the title ‘China is the Real Sick Man of Asia,’ (Stevenson 2020). The sobriquet ‘sick man of Asia’ (Yazhou bingfu) is a derogatory coinage from the turn-of-the-century Qing Dynasty, intended to denigrate China’s perceived weakness and passivity in the face of foreign aggression and territorial encroachment. The term came into wider awareness among the American public when Bruce Lee, in his 1972 film Fist of Fury, shouts at a group of Japanese martial arts attackers ‘We Chinese are not the sick man of East Asia!’ (Yau 2020). The term has long been perceived by Chinese and Chinese-Americans as a racist trope evoking China’s colonial history, and its use by the Wall Street Journal at a such a moment of geopolitical raw nerves was bafflingly tone deaf.

The use of the offending phrase quickly spread throughout Chinese state media and social media, triggering popular outrage. Reaction on the part of the Chinese diplomatic corps was immediate; the Chinese demanded an apology for the editorial and a full retraction. When the Wall Street Journal repeatedly refused to accede to the government’s demands, China’s Foreign Ministry expelled three of the top journalists from the newspaper’s Beijing bureau on February 18. Ironically, the three expelled journalists, deputy bureau chief Josh Chin and reporters Philip Wen and Chao Deng, were all seasoned China hands who were in no way responsible for the editorial itself, and no doubt would have been the first to advise against the use of the sensitive term if they had been consulted.

These three journalists were only 2020’s first victims of the retributive tit-for-tat. On March 2, the US State Department announced a punitive move to reduce the number of Chinese working in the US for China state media to 100 workers, thus resulting in the expulsion of 60 employees of five state media outlets. This ill-advised US move gave the Chinese government the perfect excuse to expel several top American journalists who had had been most active in reporting the Chinese handling of the coronavirus outbreak. On March 17, China kicked out some of the most experienced China reporters for The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal and New York Times, and forced the firing of Chinese nationals working for Voice of America and CNN (Smith 2020). Given the need for more, not less, information coming from China, these reflexive retaliatory moves by the two governments were counterproductive and regrettable.

Indeed, American reporting at this time lacked accounts from inside China, especially coverage of what was going on inside the city of Wuhan during the lockdown. Foreign reporters were not allowed into the city, and it was difficult to garner information through interviews with average citizens. An award-winning Chinese novelist named Wang Fang, who writes under the pen name of Fang Fang, was living in the city of Wuhan when the lockdown occurred. On January 25, she began to keep a diary about daily life in the city during the quarantine, publishing the entries on her Weibo account, which had 3.8 million followers. Fang Fang wrote about the facts of daily life, such as food supplies, mental health, sleep problems, and staying in touch with friends. But she was also frankly critical of many of the official policies and procedures, and her diary entries were often censored after she posted them. Her diary provided a daily catharsis for many, and began to gain some notoriety in China. Her Weibo account was suspended in February but later reinstated (Davidson 2020).

In what promised to be a welcome breakthrough in mutual understanding between China and the US during the coronavirus crisis, Fang Fang’s diary was quickly translated and published in May with the English title Wuhan Diary: Dispatches from a Quarantined City. A striking aspect of the book is that the quotidian events, public reactions, and emotional problems in Wuhan so vividly described by Fang Fang resonated with the struggles that average Americans were experiencing at the time. Appearing as it did, during the height of the Covid-19 epidemic in the US, the diary could have been an instructive first-hand account, as the events paralleled the hardships facing the American population during those months. Yet the book received scant press coverage, and the reception overall by the media was lukewarm. Conditions had already improved in Wuhan, and the dramatic news narrative of China’s struggle against the disease had begun to fade from the mainstream news feeds.

Asymmetry in the quality of popular media discourse

Another aspect of the asymmetry in the political media discourse in the two countries is the quality of the commentary. Much of the political commentary that appears in US media is carried out between highly opinionated and articulate media celebrities, who nevertheless have no academic or professional qualifications. Squeezed by the exigencies of the 24/7 news cycle, US broadcast news programming tends to give high-profile politicians and pundits a disproportionate amount of airtime when discussing US-China issues, rather than prominent China experts from academia or major think tanks. By contrast, Chinese state media, relatively indifferent to ratings and profits, tends to populate commentary shows with dry university professors and experts rather than charismatic talking heads and polemical public figures. While these carefully controlled programs invariably present carefully vetted state propaganda, they at least tend to be authoritative and historically grounded. And in dealing with issues that don’t directly pertain to Chinese politics, they are often more substantive and comprehensive than their US equivalents.

One such outlet is Guancha News (Guanchazhe wang) (Guancha News 2020a), which hosts an ongoing series of commentaries by political science professors from prestigious universities on various geopolitical and historical topics. One of the most popular and widely distributed of these programs is China Now (Chinese title: “Zhe jiu shi Zhongguo,” “This is China”), which prominently features Zhang Weiwei, an International Relations professor at Fudan University and author of numerous ultra-nationalist books on China’s rise (Guancha News 2020b). In the months after China’s epidemic situation began to stabilize, Zhang put out a series of videos documenting and contrasting the approaches of China and the US in dealing with the Covid-19 crisis. His commentaries dealt with differences in political structures, health care systems, media influences, and even cultural differences, such as China’s supposed collectivist mentality vs. the individualism of US society. The upshot of his presentations: The American system is experiencing a failure in governance, due to corruption and economic inequality, whereas the Chinese model is showing an increasing resilience and adaptability due to its centralized, scientific governance, and a focus on the material well-being of the average citizen.

The mass media system Xi Jinping has created is truly commanding, and programs such as these can be very effective in shaping and cementing the CCPs narratives. (For more on how Xi Jinping has centralized and consolidated the China media system, see Moser, 2019.) There are TV and radio outlets at all national, provincial and municipal levels throughout the country, and each week the state disseminates hundreds of hours of political news and analysis. The cumulative effect of all this programming, however biased it may be, is that average viewers are not only absorbing state propaganda, but in the process also receiving what amounts to informal minicourses in comparative history, political theory, and governance systems. As a result, it is safe to say that the educated populace in China has a much better understanding of the American political system than the average American has of the Chinese system. I was living in Beijing after the election of Trump in 2016, and I was struck by how ordinary Chinese people, even Beijing taxi drivers, would ask me cogent questions about aspects of the American system, such as the US electoral college and the importance of swing states. I daresay most average Americans could not even provide a basic description of the Chinese political structure, much less pose intelligent questions about leadership succession.

Insights for Americans from Chinese social media

If American society were to somehow be directly exposed to Chinese popular media and social media, what kinds of insights or increased cultural awareness might result? The following are just a few points of view Americans might find enlightening.

The Chinese view the American response to Covid-19 as a vindication of the China governance model.

The disastrous Covid-19 response in the US has reinforced the notion, pushed by the Chinese Communist Party, that the China model is proving to be not only viable, but in many ways superior to the American model. From the very beginning of the coronavirus outbreak, China Global Television Network (CGTN) was promoting the notion that China’s governance model, with its focus on centralization and collectivism, was better suited than Western democratic systems to address public crises such as a pandemic. When the Trump administration failed at flattening the curve of the epidemic resulting in a drastic resurgence of cases in June 2020, China state media reported the events with an air of self-congratulation, if not outright schadenfreude.

The Chinese were shocked at the Americans’ seemingly cavalier attitude toward the death rate.

Time and time again on Chinese social media the narrative that sprung up was ‘China did everything to keep the death count low. The US did everything to keep GDP high.’ Indeed, this has been one of the most common reactions among netizens in the PRC. There were expressions of genuine shock and dismay that the United States, a bastion of ‘human rights,’ could be so callous about the high death rates. Especially inconceivable to Chinese netizens were the offhand comments in US video clips to the effect that ‘The coronavirus mainly kills older people anyway.’ To those steeped in China’s Confucianist social tradition for which respect for the elderly is paramount, such sentiments were quite jolting.

The Chinese chided American resistance to medical science and the advice of experts.

From the very beginning, Chinese netizens and experts expressed surprise at the large number of Americans who simply did not take the advice of health experts seriously, particularly with regard to the wearing of face masks. The wearing of masks has been common in China and elsewhere in Asia in recent decades as a response to high pollution levels in major cities and other pandemics. Thus, the switch to facemasks was obvious and intuitively acceptable to average citizens. For the first half the year the Chinese citizenry had been inundated with information and mandates about health and safety. To them it was inconceivable that Americans would be so indifferent, or ignorant, about the scientific facts of the epidemic.

The “Security Dilemma” of US-China Relations

A longstanding analytical framework popular with international relations theorists is the “security dilemma” first formulated by John Herz (Herz 1950). Security dilemma theory regards conflicts between states as essentially arising from failures of communication, wherein one side fails to consider how their actions might be viewed from the vantage point of the other side. The task is one of ‘imaginative empathy’ – to attempt to see the effects of your actions through the eyes of the other party. Conflict avoidance between states involves recognition and understanding of the other state’s motivations and intentions, without necessarily agreeing with them. In the trajectory of Sino-US relations over recent decades, Americans have suffered from an informational deficit in this regard. The Chinese side is increasingly cognizant of how Americans view their global role and the rise of China, whereas the American side has failed to understand China’s complicated perceptions of US behavior. This American blindness to the complex and changing realities of China’s advancement in the world order will increasingly put the US at a disadvantage in negotiations and cooperation. Just as a poker player can gain advantage if they can see the cards in the opposing player’s hands, so China will be able to second-guess and outmaneuver the US, equipped with greater awareness of the other side’s default assumptions, misapprehensions and prejudices.

The degree of understanding necessary to deescalate the current crisis and create a more stable relationship requires not only more informed leadership, but greater mutual understanding at the grass-roots level, as well. This is particularly true in the US, where the quality of the leadership is directly correlated with the enlightenment of the voters. Raising our level of awareness would entail greater people-to-people contact, cooperation and constructive discourse. As long as the Chinese remain cognizant of America’s media, its memes, and its mindsets, while the US continues to see China through a set of outmoded tropes, tensions will continue to escalate. Perhaps the lesson for Americans as they move forward into the century is to start talking less and listening more.

References

Davidson, H. (2020) ‘Chinese writer faces online backlash over Wuhan lockdown diary’, The Guardian. (accessed 29 June 2019).

Feng, E. (2020) ‘As Coronavirus Spreads, U.S. Students In China Scramble To Leave’, NPR. (accessed 29 June 2019).

Guancha News (观察者网) (2020a) (accessed 29 June 2019). (Also available on YouTube (accessed 29 June 2019).

Guancha News (观察者网) (2020b) Zhe jiushi Zhongguo 《这就是中国》(China Now)’, (accessed 29 June 2019

Herz, J. (1950) ‘Idealist internationalism and the security dilemma’, World Politics 2(9). p157-180. DOI: 10.2307/2009187

IH Digital (2020) ‘Top 5 Most Popular China Social Media Apps 2020’. (accessed 29 June 2019).

Moser, D. (2019) ‘Press Freedom in China under Xi Jinping’, in Burrett, T. and Kingston, J. (eds.) Press Freedom in Contemporary Asia. London: Routledge, pp. 68-82.

Ng, K. (2016) ‘Despite being blocked, Twitter estimates it has about 10 million users in China’, Techwire. (accessed 29 June 2019).

Shao, Y. (邵一佳) (2020) “Meiguo yi zhuchiren yaoqiu Zhongguo wei yiqing daoqian, bei dadangchang daduan zhiyi’ (美国一主持人要求中国为疫情道歉,被搭档当场打断质疑… ‘American host calls for China to apologize for the epidemic, is interrupted and doubted by his colleagues…’ Huanqiu shibao 《环球时报》 (Global Times). (accessed 29 June 2019).

Smith, B. (2020) ‘The U.S. Tried to Teach China a Lesson About the Media. It Backfired’, New York Times. (accessed 29 June 2019).

Statista (2019) ‘Number of college and university students from China in the United States from academic year 2008/09 to 2018/19’. (accessed 29 June 2019).

Stevenson, A. (2020) ‘China Expels 3 Wall Street Journal Reporters as Media Relations Sour’, New York Times. (accessed 29 June 2019).

Tan, H. (2015) ‘China is losing interest in learning English’, CNBC Business News, Wealth in Asia. (accessed 29 June 2019).

Yau, E. (2020) ‘China enraged by ‘Sick Man of Asia’ headline, but its origin may surprise many’, South China Morning Post. (accessed 29 June 2019).

You, T. (2020) ‘China blasts Fox News host Jesse Watters’ ‘arrogance’, ‘prejudice’ and ‘ignorance’ after he demanded Beijing apologise over coronavirus outbreak’, Daily Mail. (accessed 29 June 2019).