This transnational collaborative special issue is an effort to assess the impact and implications of the COVID-19 outbreak in Asia. This is a two-part special issue with Part I focusing mostly on East Asia, while Part II includes case studies from South and Southeast Asia in addition to transnational geo-political assessments. Most of the essays feature probing analyses of public policies and pandemic politics, but some provide more personal reflections on life in a time of outbreak (see Chen, Cleveland, Horiguchi, and Wake in Part I).

As Michael Bartos discusses in his lead-off essay, Asia is no stranger to pandemics. In these case studies spanning the region, we find that not all governments learned the lessons of those prior pandemics while a few, notably Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan, have acted resolutely to contain transmission precisely because of lessons learned. Leadership, and these governments’ willingness to rely on science as a basis for public health countermeasures, clearly matters. On the whole, Asia has not yet faced the same coronavirus whirlwind that swept through Europe and continues to wreak havoc in the US, but there are significant variations within the region and uncertainty about the reliability of official data.

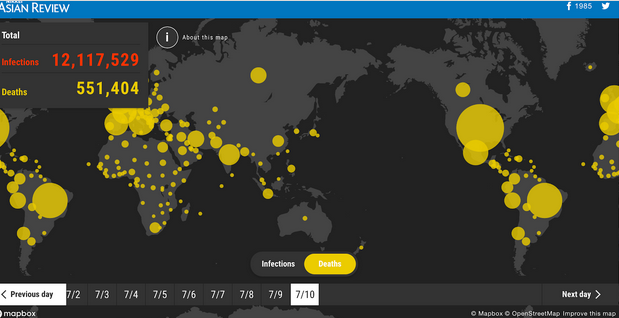

Source: Nikkei Asian Review

Pandemic Politics

Our authors examine the political ramifications of COVID-19 and how governments have exploited the crisis to advance existing agendas using the pandemic as cover, or to distract public attention from other controversial policies. For example, Samrat Chowdhury in Part II of this special issue notes that India PM Narendra Modi was, prior to the pandemic, facing large scale demonstrations against his recent initiatives to strip Muslims of their citizenship. His Islamophobia resonates among Hindu zealots, often stoking violent intolerance of diversity in an incredibly diverse society, but with his abrupt announcement of a lockdown, the demonstrations were contained, far better in fact than the COVID-19 outbreak. Modi’s shambolic mismanagement of the pandemic in India, resulting in the mass exodus of migrant workers to their home villages, demonstrates how much leadership matters. Like Indians, Americans know too well the catastrophic consequences that an inept leader can inflict. The escalating numbers of cases and deaths in India highlight the folly of the lack of preparation on the foreseeable consequences of an abrupt lockdown in a nation with creaky healthcare infrastructure, limited safety net, and large informal economy of migrant workers. Here in Part I, Michiel Baas examines the precarity of such migrant workers in India and Singapore, and how the pandemic challenges their marginalization in uplifting narratives and from public attention. In the Philippines, Quijano, Fernando, and Pangilinan argue in Part II that President Rodrigo Duterte boosted transmission with an ill-advised program (since cancelled) to incentivize people to leave crowded urban centers and return to their home villages.

The pandemic has generated opportunities for leaders, bureaucrats, security forces, and the well-connected, while reinforcing the pathologies of inequality, the force multiplier for transmission. Along the lines of the adage “never waste a crisis”, various institutions and actors have managed to turn the pandemic to their advantage by securing budgets and expanding turf while engaging in cronyism and repression and fending off reforms. The COVID-19 outbreak has also raised awareness of public health shortcomings, and the urgent need for better preparations, but in the meantime healthcare capacity will be stretched as the pandemic wanes, surges, and lingers. It is clear that wishful thinking is not a sound basis for managing pandemic risks and hopefully authorities will act accordingly. Clearly, there are powerful financial reasons for wishing risk away, but the impact of COVID-19 on public health and economic and social well-being has been catastrophic, highlighting the urgency of prudent investment in upgrading countermeasure capacities. Nations with good public health infrastructure have fared better in coping with the pandemic in terms of testing, tracing, isolating, and treating. For the destitute, vulnerable, and marginalized communities across Asia, the pandemic has highlighted their limited access to healthcare and how they are at highest risk precisely due to their lack of access to resources and networks of influence. Inequality should thus also be prioritized in the crisis response policy agenda.

There is a temptation to ascribe democratic backsliding in Asia to the pandemic, but some of Asia’s democracies (including Bangladesh, India, Myanmar, Nepal, the Philippines and Sri Lanka) had pre-existing conditions that left them vulnerable to the politics of pandemic. As Croissant argues, “The global erosion of democracy preceded the COVID-19 pandemic, but its outbreak is accelerating the dynamics of democratic regression. As governments around the world fight the spread of the coronavirus, the number of countries in which democratic leaders acquire emergency powers and autocrats step up repression is rapidly increasing. The uneven performance of many democracies in containing the pandemic and mitigating its public health effects rekindles debates about the effectiveness of democratic rule compared to authoritarian regimes” (Croissant 2020).

Indeed, there is vibrant debate about whether authoritarian governance is better suited to swiftly enacting effective countermeasures such as lockdowns and quarantines, but the relative success of Australia, Japan, New Zealand, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan demonstrate that democracies, thus far, have a reasonably good track record on containing COVID-19. Yet, as is becoming ever more apparent, the pandemic has not petered out – new outbreaks and second or third waves counsel caution against making any grand claims about the virtues of different political systems. What does seem clear is that populist governments such as in India and the Philippines have been struggling to enact coherent and consistent countermeasures. Croissant (2020) suggests that these failures might provoke a popular backlash and reinvigorate democratic institutions and practices. Perhaps, but the legitimacy of democratic despots like Modi and Duterte hinges more on their grandstanding political performances that divert attention away from their failures and failings, rather than effective policymaking beneficial to the public.

Beyond invoking emergency powers, some Asian democracies have militarized pandemic countermeasures, but as our authors contend in Part II, a security first approach doesn’t appear to be effective in containing the outbreak in nations ranging from Bangladesh and Sri Lanka to Indonesia and the Philippines. For security forces, the pandemic has been a golden opportunity to assert power, or as Jun Honna argues in the case of Indonesia (in Part 2), claw back lost turf and undo reforms and constraints imposed since the downfall of President Suharto in 1998. Similarly, Udan Fernando suggests (in Part 2) that Sri Lanka’s newly elected President Gotobhaya Rajapaksa (2019-) has managed to navigate the lockdown to sidestep constitutional checks-and-balances and reaffirm the military’s central role in the polity. Politicians hope that securitization of the pandemic response will boost discipline and stifle dissent, but to the extent that the pandemic worsens, state security may be held responsible, possibly causing a backlash.

Models of Success: Taiwan and South Korea

|

|

The essays on East Asia highlight that, in addition to robust public health systems, a successful response depends on competent leadership, capable bureaucracies, pandemic preparations, access to reliable information, and coherent crisis communications to keep the public informed and nurture trust in the government’s emergency countermeasures. Much depended on learning the lessons from previous pandemics, as well as aggressive public health policies supported by strong public health systems and consistent political leadership and messaging. This is not an affirmation of the discredited Asian values thesis, or ammunition for the democratic versus authoritarian debate, but rather highlights the importance of sound preparations, effective implementation, and civic engagement in containment efforts.

Taiwan and South Korea score high on these criteria (see essays in Part I by Rowen, Hioe, and Park). In contrast, according to Azby Brown, Japan has fared reasonably well thus far despite deeply flawed communication and mediocre leadership. He argues that public trust in government is not very high in Japan and as a result, speculates that people took the initiative to protect their health of their own volition, rather than waiting for the government to take action. Park points out that two transmission clusters in South Korea occurred among groups with little trust in government due to a history of antagonism and harassment. Members of a religious cult in Daegu and the LGBT community in Seoul were wary of cooperating with authorities, and this has hampered containment efforts because such efforts rely on cooperation and trust. In his essay on Australia, Bartos, while crediting authorities with effective countermeasures, suggests that more active public engagement is necessary for ongoing efforts towards virtual elimination of the virus. Here too, gaining community trust and cooperation by local empowerment is essential.

Pandemic Tensions and Diversions

The escalating war of words between Beijing and Washington over the COVID-19 outbreak is symptomatic of the burgeoning geo-political rivalry between the US and China. David Moser and Anonymous both write in Part I about the mutual recriminations, and how President Donald Trump’s egregious mismanagement of COVID-19 countermeasures has been exploited by China’s state media and on social media to discredit not only the president, but also democracy. Initial domestic frustrations among Chinese citizens with how the state handled the outbreak in Wuhan have shifted to outrage over US blame-mongering against China. Deflecting attention to US shortcomings and the president’s erratic performance has facilitated a triumphalist Chinese narrative and represents an own goal by Trump, handing Xi a propaganda victory. David Moser explains, “how the COVID-19 epidemic of 2020 exacerbated existing tensions between the US and China, and how these escalations in state-to-state conflict were in large part due to America’s information deficit with the PRC.” It seems clear that media representations of the other in both countries has fueled escalating mutual misunderstandings. The information deficit has also politicized the pandemic and partially explains President Trump’s decision to withdraw from the World Health Organization. As Naoko Wake explains, his race-baiting with his insistence on describing COVID-19 as the “China virus” and willful Othering has endangered Asian Americans and subjected them to prejudice and indignities that reflects something far worse than an information deficit.

In Hong Kong, following the city-state’s smart handling of the outbreak that drew on lessons learned from the 2003 SARS pandemic, Beijing has enacted national security legislation to stifle anti-government dissent. As Simon Cartledge argues, although the economic fallout will probably be severe, 2020 will be remembered mostly for the political consequences.

The implications of political developments in Hong Kong for Taiwan remain uncertain, but the essays by Ian Rowen and Brian Hioe do highlight the rapid and successful response by President Tsai Ing-wen’s government. Like Hong Kong, lessons were learned from the 2003 SARS outbreak and preparations made. Despite no lockdown, Taiwan managed border controls and quickly rolled out effective countermeasures that relied on testing, tracking, and quarantine to limit transmissions. This was a science driven approach that paid dividends but would not have been possible without the island’s excellent public health infrastructure and residents’ faith in authorities.

Japanese Exceptionalism?

Japan is something of an outlier in Asia in terms of its dilatory response by a complacent leadership that prioritized public relations over public health. The botched quarantine of passengers and crew on the Diamond Princess cruise ship in Yokohama Bay was an alarming crisis response to the first outbreak in Asia outside China (Kingston 2020a). This was compounded by the poorly monitored disembarkation of Japanese passengers, many of whom returned home on public transport. In traditional media and on social media, Prime Minister Abe Shinzo was severely criticized in February for being disengaged, and there was considerable speculation that his government was not ramping up testing in order to suppress the number of cases. His abrupt decision at the end of February to order the closure of schools nationwide without consulting relevant experts or educational authorities smacked of politics, trying to appear decisive, but the public backlash was harsh, especially from working parents who suddenly had to sort out child-care.

Abe’s abrupt school closure and layoffs of non-regular workers derail Womenomics |

The Japanese government maintains that its approach to testing was driven by a cluster-based approach that devoted limited resources to tracking clusters of transmissions and tracing contacts for infections, but by mid-March this strategy was no longer working because more than half of transmissions could not be traced. It appears that until then, the government held out hopes for staging the 2020 Olympics, worrying that travel bans, and a declaration of national emergency would eliminate such prospects. Moreover, PM Abe hoped that a planned summit with President Xi in April might still be possible. By the end of March, the Olympics were postponed to 2021 and the summit was shelved. This set the stage for Abe’s declaration of a limited state of emergency covering just 7 prefectures, extended nationwide a week later. As infections surged, it appeared Japan’s luck was running out.

The “Japan model” and the government’s erratic response have drawn harsh domestic criticism (Yano 2020). In his essay here, submitted in June before Abe disbanded his Expert Group, Ambassador Togo Kazuhiko gives Abe the benefit of doubt on his crisis response. Abe, however, has sunk in Japanese public opinion polls, partly due to negative perceptions of his crisis management (Takeuchi 2020). As Takeuchi reports, in May 55% of the public disapproved of his pandemic response while just 36% approved, but as of June positive perceptions rose to 46%. A subsequent Kyodo poll showed his approval rating slipping to a near record low of 36.7 percent while disapproval surged to 49.7 percent, owing in part to suspicions of cronyism involving government outsourcing of pandemic countermeasure services, but mostly due to a political scandal in his party related to election rigging by a close associate and his wife (Mainichi 2020a).

As of mid-2020, Japan has recorded less than 1,000 deaths from COVID-19; the number of cases has increased as restrictions were eased in June, but that is mostly a function of increased testing. In early May, under intense criticism by health experts and the public, the government suddenly eased eligibility criteria for getting tested and approved the use of antigen tests to supplement the limited capacity for PCR tests (Reuters 2020). Prior to that, only people with a fever of at least 37.5 C (99.5 F) for four consecutive days qualified for testing, which raised concerns over the possibility that such a rule would fuel community transmission by sending infected people home. As Azby Brown notes here, the government has belatedly tried to make the case for limited testing in terms of not overwhelming hospitals and testing centers with the “worried well”. Some health professionals defend the cluster-based approach, arguing that it was pragmatic and effective by focusing on super-spreaders (Sakamoto 2020), but as Brown notes, some prominent epidemiologists remain quite critical of this limited testing approach.

In a nation of 126 million, with 28% of the population over age 65, Japan seems to have dodged the bullet for the time being. Interestingly, this relative success has not helped Abe as his public support ratings have sunk and his negative ratings have spiked. Basically, the public has not credited Abe with containing the outbreak as he is blamed for waiting too long to declare a state of emergency and not showing leadership in the crisis (Kingston 2020b). So, if Abe doesn’t get any credit for the limited toll of the outbreak, how is this relative success explained? Early on the public adopted sensible precautions and stuck with the program, wearing masks to impede transmission, staying home and observing social distancing guidelines. Moreover, levels of personal hygiene are high and relatively few people have the habit of handshaking, hugging and kissing. Some speculate that mandatory TB vaccinations are a factor while others even argue that Japanese language itself is a barrier to transmission because the way it is spoken doesn’t project droplets. This linguistic explanation, however, overlooks the high death toll a century ago during the Spanish flu when over 400,000 Japanese died.

Clearly, Tokyo Governor Koike Yuriko has done a better job at communicating with the public. She holds frequent press conferences and has consistently urged people to stay home and businesses to shut down. There is no penalty for non-compliance, but by engaging the public she has earned their trust and won their support, recently winning reelection by a huge landslide. Her prominent position as head of a megapolis of 13 million residents, together with national media attention, have spread her message across the archipelago at a crucial time when cases and anxieties were rising. Abe’s few press conferences were carefully stage managed and he could not match her media presence. She once worked as a newscaster on television and understands traditional media and social media in ways that Abe clearly doesn’t. Abe was relentlessly mocked over his pricey but inadequate policy of distributing two masks to every household, called “Abenomask”, that drew on public dissatisfaction with the sputtering range of policies called Abenomics.

PM Abe and Deputy PM Aso in masks during Diet deliberations |

Moreover, netizens blasted a video Abe tweeted of him coping with lockdown at his well-appointed residence where he cuddled his dog, sipped tea and channel surfed, suggesting he was totally out of touch with public concerns. It also did not help that his inner circle of advisors on managing the pandemic were all elderly politicians who viewed the crisis through the prism of political implications rather than the science of epidemiology, a major contrast to President Tsai Ing-wen’s crisis team in Taiwan (Kasuya and Tung, 2020). At the end of June, Abe abruptly disbanded his Experts Group of scientific advisors in favor of a panel of celebrity scientists and others lacking a background in epidemiology. Apparently, the original Expert Group made awkward policy suggestions at odds with the prime ministers’ political agenda, recommending, for example, against easing constraints on business operations. With the economy tanking, Abe prefers to boost business activity while the Experts Group was warning of the risks of doing so. Yet again, it seems Abe remains complacent about mitigating public health risks. He is also in trouble over his strong arming of the bureaucracy to approve the domestically produced drug Avigan for treating COVID-19 (Sakaguchi 2020), especially now that the results of initial clinical trials have been disappointing (Mainichi 2020b).

In contrast to Abe’s poor leadership, Nathan Park argues here that South Korean President Moon Jae-in won public trust and admiration for his deft crisis response countermeasures, including large scale testing and tracking, scoring an unprecedented landslide election victory in the April legislative elections. He provided resolute political leadership, rallied public compliance, and relied on a science driven response while avoiding a hard lockdown. Like Taiwan, South Korea is a model for how to manage a pandemic with extensive testing, tracing, tracking, and treatment, quite in contrast to Japan’s very limited testing and tracking. A second wave of cases in June that erupted in Seoul’s gay district highlights the challenges that remain in containing the outbreak as communities that have little reason to trust the government are less inclined to comply with guidelines and more concerned with protecting their own privacy.

Conclusion

Trust, as we see in this special issue, is hard to earn and just as easily lost. In situations where the public has learned to be skeptical of their government, this can leave people to their own devices. In Japan, they responded well (mask wearing, handwashing, social distancing), but this is not a model for nations without high levels of social cohesion and social capital. Moreover, shifting responsibility from the state to the people prevents a coordinated response and heightens the risk of amplifying the negative consequences where social distancing is not an option and access to healthcare is limited. Based on the cases of Taiwan and South Korea, consistent messaging and conveying reliable information are crucial to gaining public cooperation and coping with the coronavirus. Alas, Modi and Trump have demonstrated the folly of not doing so.

Sources:

Croissant, Aurel. (2020) “Democracies with Preexisting Conditions and the Coronavirus in the Indo-Pacific”, The Asia Forum, June 6.

Kasuya, Yuko and Hans. H. Tung, 2020. “Taiwan has a lot to teach Japan about coronavirus response” Nikkei Asia Review, April 20.

Kingston, Jeff, 2020a. “Japan’s response to the coronavirus is a slow motion train wreck”, Washington Post, Feb. 21.

Kingston, Jeff, 2020b.”COVID-19 is a Test for World Leaders. So Far Abe is Failing”, The Diplomat, April 23.

Mainichi, 2020a. “Ex-minister’s arrest pushes support for Abe’s Cabinet lower: Kyodo poll”, June 21.

Mainichi, 2020b. “Avigan study fails to demonstrate benefit in COVID-19 study”, July 10.

Sakaguchi, Yukihiro, 2020. “Abe’s arm-twisting of bureaucrats paved way for Avigan blunder”, Nikkei Asian Review, June 14.

Sakamoto, Haruka, 2020. “Japan’s Pragmatic Approach to COVID-19 testing”, The Diplomat, June 26.

Takeuchi, Yusuke, 2020. “Abe’s Approval plunges 11 points after missteps on coronavirus aid”, Nikkei Asian Review, June 8.

Yano, Hisahiko, 2020. “Japan’s Coronavirus response offers little clarity and few lessons”, Nikkei Asian Review, May 26.