Abstract: In Japan, sensō koji (war orphans) are often identified as furōji (juvenile vagrants). The dominant image of sensō koji is therefore a street child engaging in a variety of adult survival activities in such cities as Tokyo after the war’s end. This essay aims to problematize this myth. In the first part, I reconsider the meaning of koji, sensō koji and furōji as socially “constructed” terms after the onset of the Meiji Era (1868-1912). In the second part, I focus on the voices and experiences of the majority of sensō koji, who were taken into their relatives’ homes immediately after the loss of their parents. The war took the lives of many children. Sensō koji survived. However, it was only since the 1970s that they began to speak about their wartime and postwar experiences to fulfill their obligation. Did the wartime state truly “protect” the nation’s children? Their ultimate goal seems to be to answer this question.

Keywords: orphans, postwar Japan, origin and representations of sensō-koji (war orphans), the U.S. bombing of Japan, protection of children

***

Many [war orphans] lived in railroad stations, under trestles and railway overpasses, in abandoned ruins. They survived by their wits—shining shoes, selling newspapers, stealing, recycling cigarette butts, illegally selling food coupons, begging (Dower 1991: 63).

|

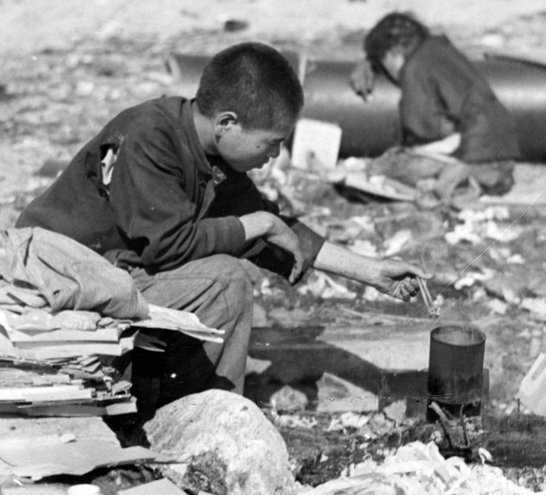

Sensō koji in Kita-ku, Osaka, using an empty can to cook. |

Sensō (war) koji (orphan) is the Japanese term for “war orphan.”1 In contemporary Japan and in the Anglophone world, people associate sensō koji with the images that John Dower provided in the context of the postwar era, that is, after Japan’s defeat by the Allied Powers on August 15, 1945. Hence, the documentary film on sensō koji made in 2015, for example, bears the title of Sensō koji tachi no yuigon: Jigoku o ikita 70 nen [The Testament of War Orphans: Having Lived in Hell for 70 Years], that is, 70 years since Japan’s defeat. Yet, many of these children became orphans, days, months, or even years before Japan’s capitulation. If so, why did they suddenly appear, as if someone placed them on the stage of postwar Japan, that is, a product of the defeat? Did they all experience the lives of street children as described by Dower? Who are sensō koji after all? Have they ever achieved liberation from that name? This essay presents my pursuit of answers to these questions.

War Orphans Who Were Not Named Sensō Koji

The word koji (孤児) originates in ko (孤), one of the six categories of mukoku no tami (無告の民), meaning “those people (tami) who are alone in the world and have no one to turn to (mukoku).2 Ko was defined as “a child younger than age 16 without a father.” Koji, however, seems to have been used as a standard word for “orphan” since the beginning of the Meiji Era (1868-1912), when the state began to incorporate all school-age children into the system of national education.3 A dictionary definition of koji is a “a child who is deprived by death of parent(s).” Yet, the meaning of koji also includes cases involving the disappearance of the parents, as well as of the child having become lost or otherwise separated from parents, who have not come forward to claim it. In this case, war, natural disaster, such as earthquake, famine or epidemics, or the poverty of the parents is often seen as the root cause of the child’s status as koji. Regardless of its cause, the image of koji is always negative: alone, unhappy and poor.

Since the late nineteenth century, elite social reformers in Japan (bureaucrats, social workers, scholars, and education specialists) struggled to redeem the honor of orphans as “the nation’s children,” while trying to suppress the term koji. In 1898, an anonymous author in the journal Rikugō Zasshi (六合雑誌)4 wrote that he felt sick at the sight of the numerous prisons in Tokyo, and lamented the state’s total lack of interest in building public orphanages.5 The state, he wrote, could transform orphans into “courageous patriots willing to sacrifice their lives for our country” far more easily than rehabilitating adult prisoners (Editorial 1898: 64). In 1904, another article appeared in the journal Chūō Kōron (中央公論), in which the author passionately argued that the state should ban the use of the word koji, which defames the orphaned children (Ōta 1904). Indeed, many existing orphanages at that time followed his advice and dropped the word koji from the names of their institutions.6

The first Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895) and the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905) deprived an unknown number of children of their fathers. Most soldiers in these wars were “professional soldiers” (shokugyō gunjin), and sons of “professional soldiers” were expected to follow their fathers’ careers. Bereaved military officers’ families were well protected by the state. Hence, these soldiers’ children rarely ended up in orphanages. Still, the bereaved families of low-ranking soldiers had to send their children to orphanages due to the inadequate pensions they received. Tokyo Koji-in (Tokyo Orphanage), for example, accepted the first two “war orphans” in 1904, nine months into the Russo-Japanese War (2003: 151). Another arrived in the same year (ibid: 163). Nonetheless, these children were not named sensō koji. Having accepted these “war orphans,” the Tokyo Orphanage created a new category named gunjin iji or “honorable child left by a soldier father.”

The Pacific War (1941-1945) took the lives of unknown numbers of children and orphaned more than 120,000 children in Japan. The majority of these orphans were the children of civilian parents, the victims of the strategic bombing and fire- bombing raids by the U.S. Army. In March 1944, the state “recommended” enko sokai, evacuation of the family to relatives living away from major cities. In June of the same year, the state “implemented” shūdan sokai or “group evacuation,” under which school children from age 8 to 12 living in seventeen Japanese cities were separated and evacuated as a group with their classes to the countryside. In January 1945, first- and second-graders from age 6 to 8 were added, although many parents were reluctant to let such small children participate in the group evacuation and either kept them at home or chose enko sokai (Kaneda Mari, personal communication).

During the summer of 1944, the first group of school children in Tokyo participated in the group evacuation, and other major cities followed. On March 10, 1945, the ferocious fire bombing of Tokyo killed approximately 100,000 people in a single night and created hundreds of thousands of refugees (Selden 2009: 84-85). The bombing continued in Tokyo and sixty-four other cities in the final months of the war. During this final phase of the war the term koji again became the target of harsh criticism. This time, a group of young schoolteachers demanded that the term koji be replaced by kokuji (国児) [the nation’s children]. The wartime state welcomed this name change and issued the following document on June 28, 1945.

For those infants, children and youth, who lost their protectors due to the war, the state will make every effort to protect and nurture them. The state will make sure that these children never forget their mission to remember that they are the offspring of martyrs, and to cultivate their fighting spirit to revenge the deaths of their parents. With this state policy, the parents will be able to fight to the end of the decisive battle on the mainland, without worrying about their children in the event of their own unfortunate deaths. … How should our society, or ordinary citizens, view these children? It is not enough to pity them. With abundant gratitude toward their deceased parents, our society must offer pity and compassion to these children. Thus, we propose to end the use of koji and call them kokuji.

The above was an “outline of policies” concerning the protection of war orphans: it was not an official edict. However, the teachers’ group, having been assured that it would be issued, published the following statement in the Asahi Newspaper on June 15, 1945.7

The [civilian] parents of war orphans immolated themselves for the state. … These war orphans lost their biological parents, and yet they met their new parents whose name is “the state” (kuni). [War orphans] will entrust their future to the state and offer their lives to the state. Their tragic fates have turned to happiness and excitement, now that they have met their new parent. They are no longer koji but kokuji, the nation’s children (Asahi Newspaper, June 15, 1945).

Despite all these efforts to vanquish koji, lasting more than half a century, the word made a remarkable return after Japan’s defeat.

Numbering, Categorizing and Defining Sensō Koji

“The statistics of sensō koji taken just before the war’s end has not been found anywhere,” so writes Henmi Masaaki (1994: 103). The statistics of sensō koji taken after Japan’s capitulation does exist, but depending on who counted them and when, the number fluctuates greatly. Today, most historians rely on the document issued by the Ministry of Health and Welfare in 1948. This document, however, is not about sensō koji but about koji. The document records the nationwide total number of koji (from age 0 to 18) as 123,511 and divides them into four groups: “war orphans” (28,248), “repatriated orphans” from Japan’s overseas empire (11,351), “general orphans” (81,266), and “abandoned or lost children” (2,647). “War orphans” is defined as: “those children who lost [both] parents, who were either directly engaged in armed combat or were killed by the enemy’s bombing. This category also includes those children who lost one parent in combat or bombing while another parent died of a different cause” (Kitagawa 2006: 28). “General orphans” as well as “abandoned and lost children” included a significant number of children whose parents were missing, which could include parents killed during the war. Hence, there is a consensus among contemporary scholars that, in the immediate postwar era, all 123,511 children should be considered “war orphans” (sensō koji).

|

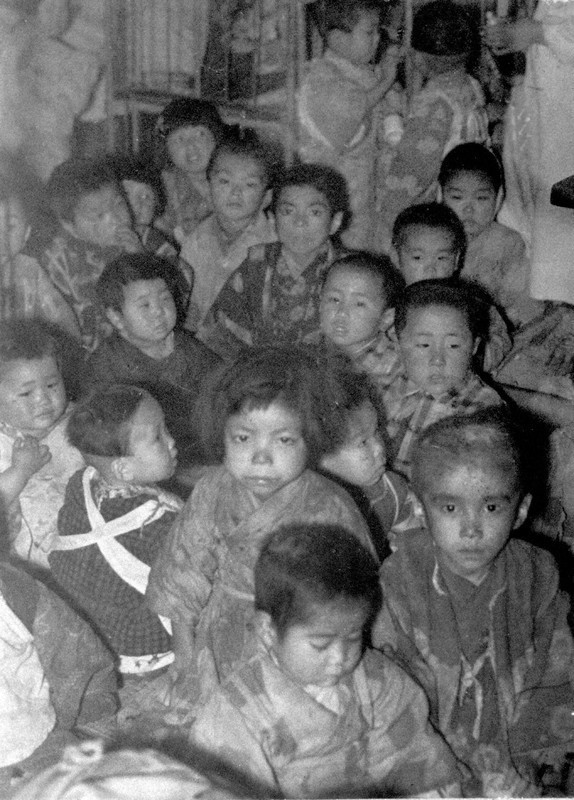

Sensō koji at the Yōiku-in in Itabashi, Tokyo. |

The postwar Japanese government, however, counted them too late (February 1948), so that many “war orphans” existing in the immediate postwar era were excluded from the official count. More than 1,000 war orphans in Okinawa were excluded.8 It remains unclear whether the war orphans of Korean, Taiwanese and Chinese immigrants to metropolitan Japan were counted. Moreover, Kaneda Mari, who is the principal informant for my research, firmly believes that many more were excluded, including herself, despite the fact that she perfectly fits one of the official definitions of sensō koji: her mother and two sisters were killed in the March bombing of Tokyo, and her father died of illness several years earlier.9

Kaneda, who was born in 1935 in Tokyo, was one of about two hundred students of Asakusa Fuji Elementary School, who were evacuated to Miyagi prefecture in June 1944. She was a third-grade student and 9 years old. Had she stayed in Miyagi until the war’s end, she said, she would not have been notified of the deaths of her mother and two sisters until after the war’s end.10 However, on March 9, 1945, Kaneda boarded the night train and returned to Tokyo, together with all the sixth-graders who were to take an entrance examination for middle school. Kaneda was with them, because her mother had already asked the school to return her daughter home in Tokyo, for she had decided to switch to enko sokai, which allowed her to stay with her three daughters.

In the morning of March 10th, when Kaneda arrived at Ueno station in Tokyo, seventeen square miles of the city had already been burnt to the ground, with fires continuing to rage in numerous spots. The bombing killed the parents of one hundred children of her school. Those students who were still at the evacuation site in Miyagi were not notified of the loss of their parents, brothers, sisters, and/or grandparents until several months later. Kaneda, however, was left alone in burned out Tokyo on March 10, without being able to return to Miyagi. Thereafter, she was circulated among the families of one relative after another. Six years later, at around age 15, an izakaya (Japanese pub) offered her room and board in exchange for her labor as a maid. She was finally “independent.”

Kaneda insists plausibly that the number 123,511 excludes numerous such war orphans as herself, who were cared for by relatives or acquaintances prior to 1948: the state classified them simply as having been “adopted” into the extended family. Kaneda also believes that, immediately after Japan’s surrender, the newly formed government imposed a gag order on the principal of each school that participated in group evacuation of its students. Consequently, the number of evacuee children, who lost their parents and therefore continued to stay in evacuation sites even after the war’s end, was permanently concealed.

There was another “problem” with this figure of 123, 511: children of broken and/or impoverished families, whose parents were alive, may have been included in the number “by mistake,” largely because they were on the street just like sensō koji. They were called furōji [juvenile vagrants]. For the postwar government, it was essential to separate furōji from sensō koji, because the former were suspected of disturbing public peace and social order. The editorial of the journal Shakai Jigyō [Social Work] published in 1946 insisted that most furōji (浮浪児) had already become furyōji (不良児), that is, “juvenile delinquents.” In the same journal published in 1948, Takeda Toshio, a social worker, wrote, “Even though we call them sensō koji, more than 40 percent of them have already become furōji (1948: 1). These reports created what I call sensō koji-cum-furōji. They were “hunted, rounded up and captured” (karikomi) by the police, and sent to shelters, prisons or relatives (if any were willing to accept the child).11 However, many quickly ran away from those facilities, and returned to what Yoshioka Genji later called “the land of freedom,” the places they inhabited before being captured (1987). The reports indicated that sensō koji-cum-furōji committed such crimes as theft, pilferage, embezzlement, arson, black-market trading, gambling, prostitution and consuming and selling illegal drugs.12

|

Children caught and detained through karikomi. |

Sensō koji-cum-furōji were expected to go through “moral rehabilitation” to become part of the new nation. Sensō koji no kiroku [Records of the Voices of War Orphans] (1947), a rare report on the voices of sensō koji-cum-furōji published immediately after Japan’s capitulation, sheds light on this process.13 Hagiyama Gakuen (hereafter Hagiyama) was originally a reformatory for young delinquents, established as part of the Tokyo Metropolitan Orphanage in 1897. As the number of its inmates increased, it was moved to the eastern edge of Tokyo in 1936. After Japan’s defeat, Hagiyama received more than two hundred sensō koji-cum-furōji.14 In 1947, Shimada Shōzō, the then principal of Hagiyama, and Tamiya Torahiko, collected the stories of the children of Hagiyama and published them as a book. The collection is divided into two parts: “reminiscences” (recalling the past before arriving at Hagiyama) and “life at Hagiyama” (about the period after arriving at Hagiyama). What follows is the voice of Shōichi, a sixth-grade boy, who reminisced about his days as a war orphan before he arrived at Hagiyama.

A truck came and picked me up with other kids. I tried to search for my friend, but in vain, and we soon arrived at the shelter. … The following morning, a kid named Itabashi approached me and told me to run away together and I agreed. After dinner, we sneaked under the shelter’s veranda. But the shelter’s supervisor came with a flashlight and directly hit my face with the light. We were found and beaten on our butts with a bamboo stick. We were then stripped, thrown into a cell, and kept there overnight. Though they gave our clothes back to us in the morning, we were angry and ran away before breakfast. We were chased but hid in the wheat field. Soon, we saw a train approaching the station and its smoke shrouded us. We got on the train, and returned to Ueno.15 From there, we went to Tamachi, and then to Shibaura where we stayed for about half a year (Tamiya 1971: 70-72).

|

Sensō koji smoking at Ueno. |

In Shibaura, Shōichi faced police capture twice. The first time, he ran away, but the second time he was caught and taken to a shelter. There, he met his friend by chance, and together they were taken to Hagiyama with twenty-eight other children.

In the section of “life at Hagiyama,” however, I could not find Shōichi’s voice. Instead, I found the voices of another sixth-grader, Toshio, who called Hagiyama “Boys Village,” apparently after “Boys Town” in America founded by Father Edward Flanagan. Father Flanagan visited Hagiyama in 1947. Toshio wrote:

[During the summer session] our teachers took us to the swimming pool of the nearby Commerce University. They also took us to see the movie about “Boys Town” in the United States. Now, the summer festival [honoring our ancestors] on July 13th is over. Since Father Flanagan’s birthday is on the same day, we also celebrated his birthday. … The motto of Boys Village is “be healthy, honest, and harmonious.” Keeping this motto in mind, I will do my best in both schoolwork and vocational training. As a Japanese boy who is ready to rebuild our country, I have been leading a happy life [at Hagiyama] (ibid: 101-102).

The contrast between the boy before “reform” and the boy after “reform” is crystal clear. Was Toshio pressured to write the way he did, to demonstrate the result of “reform” and leave Hagiyama? While I cannot answer this question, I argue that furōji were unquestionably “war orphans,” as Morita Shōzō wrote.

Among those furōji, or among those who are treated as sensō koji, there indeed are those who lost their parents to the war. However, there are also kids who pretended to be, and acted like, sensō koji. Although their parents are alive, they may have disappeared for survival reasons, leaving their children alone and with no means to contact them. They therefore believe that they too are orphans (1950: 130).

By one informed estimate, sensō koji-cum-furōji occupied only about 10 percent of the 123,511 war orphans (Kitagawa 2006: 28). Nonetheless, attracting most interest among journalists and social workers, they came to represent all war orphans.

The Voices of Former Sensō Koji from the 1970s

When did sensō koji begin to speak with their own voices? The earliest date is probably 1967, when Nosaka Akiyuki (1930-2015) published a semi-fiction titled Hotaru no haka [Grave of the Fireflies]. In 1975, Nishimura Shigeru (1925-2016) published Ame ni mo makete kaze nimo makete [Defeated by Rain and Defeated by Wind]. In 1977, Takagi Toshiko published Garasu no usagi [A Rabbit Made of Glass]. These writers later achieved fame because of the publications of their gripping autobiographies and continued to publish books of fiction and semi-fiction to let their young readers know the misery of the war. I focus, however, those sensō koji who began to speak out much later, in the 1990s. They are “amateur” speakers and writers, who participated in groups to share their experiences with the youth of present-day Japan. Most of them are sensō koji who constituted about 90 percent of the 123,511 war orphans: they were taken into their kin’s home soon after they became orphans. Among them is my informant, Kaneda Mari, who gathered these amateur speakers and formed Sensō koji no kai [Association of War Orphans] in 1997. Once I asked her, why so late? She explained it this way. First, because life as a war orphan was so traumatic, she first wanted to “investigate” what happened in the aftermath of the March 10, 1945 bombing in Tokyo, before coming out as sensō koji. Second, she was pressured to feel indebted to her relatives while they were still alive, even though they did not let her attend school. She therefore waited until those relatives had gone, before forming the Association of War Orphans. She then presented herself to me as a “former” war orphan, having established her own family.

In 2008, the Association of War Orphans held an event in downtown Tokyo, which featured Nagata Ikuko as a speaker. Nagata was a third-grade student of Kawa-minami Elementary School at the time of the March bombing. Like Kaneda, she had participated in the 1944 group evacuation to the temple in Niigata prefecture, leaving her parents, three older sisters, and one brother in Tokyo.

On March 3, 1945, twenty sixth-grade students left [the evacuation site] for Tokyo for a graduation ceremony. After March 10th, we [on the evacuation site] were unable to communicate with these twenty students. Letters that I had often received from my family also stopped. Rumors soon spread that Tokyo was heavily bombed, became a sea of fire, and our school and many houses were burned down. … In April, our head teacher returned to Tokyo to gather more information. Soon after, a couple of Buddhist monks visited us and began reading sutras. Our teacher called the names of children one by one who were orphaned. I was one of them. I learned that my parents and sisters all perished, the only exception was my brother. … We also learned that those six-graders [who returned to Tokyo on March 3] had been missing since then, except for one.16

Two months after Japan’s defeat, Nagata, together with the other twenty or so children who had lost their homes, were moved to a nearby inn. They stayed there for more than half a year. Around the end of March 1946, her maternal aunt finally came to pick her up, and brought her back to Tokyo. “My aunt and her family were kind to us when my parents were alive. Now that they were gone, she was a different person,” said Nagata. She was with this aunt for three months and ran away. Other relatives refused to take her. Luckily, her brother, demobilized from the army, returned to Tokyo and they were reunited. Yet, life without any help from their relatives was cruel until each became independent. Unlike those who wrote (or spoke out) about their wartime experiences in the 1970s, Nagata did not speak of the horror of the bombing, because she was not in Tokyo. Rather, her narratives moved calmly, from the wartime to the postwar, from the life on an evacuation site to the life in Tokyo with her relatives, and the hard life of sensō koji in postwar Japan.

In the summer of 2017, the Association of War Orphans closed its activities due to the members’ old age. Kaneda, however, continues to gather and publish the narratives of former war orphans. Her ultimate goal is to collect the narratives of those who became orphans, due to the bombing of not only Tokyo and other cities in Japan, but also all other cities of the world, including Guernica in Spain bombed by the German Army and Chongqing in China bombed by the Japanese Army.

Epilogue

On April 18, 1942, joint American Army-Navy air forces dropped a bomb in Tokyo, in reprisal for the Japanese surprise attack on the American naval base at Pearl Harbor on December 8, 1941. The very first child killed in the U.S. bombing was a middle school boy named Ishide Minosuke. Saotome Katsumoto, the founder of the Tokyo Air Raid and War Damages Resource Center, describes how Ishide Minosuke was killed and how society reacted to his death.

On April 18, 1942, sixteen B25 fighters of the U.S. Army made a surprise attack on Tokyo. In Katsushika Ward in downtown Tokyo, one B25 rained sixteen shells on the Mizumoto Middle School, killing Ishide Minosuke, a fourteen year old boy. The planes went on to China, but two of them, out of fuel, were forced to land on Japanese occupied territory. Eight American soldiers on board were arrested by the Japanese army, and three, who confessed that they mistook the school building for a military barrack, were sentenced to death as, according to the court document, “these American beasts and demons killed and injured little ones.” The tomb of Ishide Minosuke was quickly built on the compound of Hōrinji Temple near the school. From then on, until Japan surrendered to the Allied Forces, many young boys, who aspired to be fighter pilots, paid visits to Minosuke’s tomb and pledged to revenge his death (Saotome 2013: 44-47).

Ishide Minosuke was not orphaned but killed. Today, we know little of those children killed in the bombing in Japan. Henmi laments the fact that “we are unable to know the ages of those 110,000 people killed by the bombing in Tokyo.” However, he urges us to use the following formula to estimate the number of child fatalities.

The bombing of Osaka from March 1945 to the end of the war killed 2,498 people living in the wards of Naniwa, Taishō, Ten’nōji and Abeno. Among them, 308 were children age 1 to 10 (12.3 percent), and 217 were children age 11 to 20 (8.6 percent) (1988: 36).

In other words, about 20 percent of the total victims of bombing could be children under age 20. If so, about 20,000 children died in air raids in Tokyo, and about 120,000 children died in air raids throughout Japan. Henmi thus argues that the evacuation order, which was implemented but not enforced, failed to save many children (1988: 36, see also Yoneda 2015). Were they also treated as martyrs of the war, like Minosuke? Probably not. Their parents, if they survived, surely mourned their children’s deaths and remembered them. If they did not survive, these children’s voices evaporated forever. But did they?

Sensō koji survived. In both Europe and East Asia, the first half of the 20th Century became the century of war orphans. The Geneva Declaration of the Rights of the Child, which was issued by the League of Nations in 1924, stated that “men and women of all nations” must offer protection to all children who lost it “beyond and above all considerations of [children’s] race, nationality or creed.” Nevertheless, a credible international body to protect the life of war orphans was missing. Instead, the wartime state and the postwar state were required to be the main protector of war orphans.

The sudden change of the word kokuji (the nation’s child) to koji (orphan) at the divide of August 15, 1945, however, did not change the life of sensō koji. They are not the products of postwar Japan but are the products of the war. The postwar Japanese government, which since 1953 has offered hefty pensions to the bereaved families of fallen soldiers, has not yet paid so much as a penny to the war orphans of civilian parents. There is a pamphlet that Kaneda wrote some years ago. It is titled Sensō koji: katarenai kodomo tachi [War Orphans: Children Who Cannot Speak Out]. She wrote:

Most war orphans shut their mouths and won’t speak of their past. They do not want to remember, for doing so makes them feel miserable. Or, they will be kept on public display. They won’t tell their stories even to their spouses or children. They believe that none can understand their pain (n.d.: 1).

But she spoke, almost fifty years after the war’s end. Sensō koji belong to the last group of people who directly experienced Word War II. At the time of Japan’s defeat, their ages varied from 0 to 18. Accordingly, they spoke and wrote their wartime experiences at different times of the postwar era. The voices of sensō koji have accumulated over several decades, and among them, I believe, we can also hear the voices of the dead.17

References

Aochi, Shin. 1951. “Furōji: Sensō gisei-sha no jittai” [Juvenile Vagrants: The Truth about the War Victims]. Fujin Korōn 35: 70-75.

Asai, Haruo. 2016. Okinawa-sen to Koji-in [The Battle of Okinawa and Orphanages]. Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kōbunkan.

Dower, John W. 1999. Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II. New York: The New Press.

Editorial. 1898. “Seifu wa koji-in jigyō o bōkan subekarazu” [The State should not Ignore the Enterprise of Orphanage]. Rikugō Zasshi 12: 25: 62-66.

Editorial. 1946. “Shūsen-go no jidō hogo mondai” [The Problem of the Protection of Children after the War’s End]. Shakai Jigyō 29: 1: 2-9, 15.

Fish, Robert A. 2009. “‘Mixed-blood’ Japanese: A Reconsideration of Race and Purity in Japan.” In Japan’s Minorities: The Illusion of Homogeneity, edited by Michael Weiner, p. 40-58. London: Routledge.

Henmi Masaaki. 1988. “Nihon gakudō sokai-shi kenkyū josetsu” [Introduction to the Study of the History of School Children’s Evacuation in Japan]. Hokkaidō daigaku kyōiku gakubu kiyō 51: 17-36.

___________. 1994. “Dai-niji sekai taisen go no Nihon ni okeru furōji, sensō koji no rekishi” [The History of Juvenile Vagrants and War Orphans in Post World War II Japan]. Nihon no Kyōiku Shigaku 37: 99-115.

___________. 2007. “Haisen chokugo no Nihon ni okeru furōji, sensō koji no rekishi [The History of Juvenile Vagrants and War Orphans in Post-Defeat Japan]. Hokkaidō daigaku Daigaku-in kyōiku gakubu kiyō103: 11-53.

Kaneda, Mari. 2002. Tokyo dai-kūshū to sensō koji [The Great Bombing of Tokyo and War Orphans]. Tokyo: Kage Shobō.

___________. n.d. Sensō koji: katarenai kodomo tachi [War Orphans: Children Who Cannot Speak Out].

Kanō, Mikiyo. 2007. “‘Konketsu-ji’ mondai to tan’itsu minzoku shinwa no seisei” [The Problem of ‘Mixed-blood Children’ and the Formation of the Myth of a Homogenous Japan]. In Senryō to sei, edited by Okuda Akiko, et al, pp. 213-260. Tokyo: Impact Shuppan-kai.

Kawasaki, Ai. 2010. “Dai-niji sekai taisen go no Nihon e no enjo busshitsu: LARA to UNICEF o chūshin ni” [Material Aid to Japan After World War II: LARA and UNICEF]. Ryūtsū Keizai Daigaku Shakai Gakubu Ronsō 20: 2: 119-128.

Kitagawa, Kenzō. 2006. “Sengo Nihon no sensō koji to furōji” [War Orphans and Juvenile Vagrants in Postwar Japan]. Minshū-shi Kenkyū 71: 27-43.

Lee, Seungiun (李承俊). 2019. Sokai taiken no sengo bunka-shi [The Postwar Cultural History of the Experiences of Evacuation]. Tokyo: Seikyū-sha.

Morita, Sōichi. 1955. “Sensō koji no yukue” [Wandering Journeys of War Orphans]. Fujin Kōron 40: 130-133.

Narita, Ryūichi. 2010. “Sensō keiken” no sengo-shi: Katarareta taiken, shōgen, kioku [The Postwar History of the Narratives of Wartime Experiences: Experiences, Testimonies and Memories]. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten.

Nomoto, Sankichi. 1998. Shakai fukushi jigyō no rekishi [The History of the Works of Social Welfare]. Tokyo: Akashi Shoten.

Ōta, Hiroka. 1904. “Tokyo kojiin” [Tokyo Orphanage]. Chūō Kōron 19: 81-83.

Roebuck, Kristin. 2016. “Orphans by Design: ‘Mixed-blood’ Children, Child Welfare, and Racial Nationalism in Postwar Japan.” Japanese Studies 36: 2: 191-212. Online version accessed here, pp. 1-35.

Saotome, Katsumoto. 2013. Watashi no Tokyo heiwa sanpo [My Peace Walk in Tokyo]. Tokyo: Shin Nihon Shuppan-sha.

__________. 2011. “Reconciliation and Peace through Remembering History: Preserving the Memory of the Great Tokyo Air Raid.” The Asia Pacific Journal 9: 3: 1-8.

Sensō koji no kai, ed. 2009. Sensō koji tachi no hajimete no ibento kiroku-shū [Compilation of the First Narratives of War Orphans]. Tokyo: Sensō koji no kai.

Tamiya, Torahiko, ed. 1971 (orig. 1947). Sensai koji no kiroku [Records of the Voices of War Orphans]. Tokyo: Taihei Shuppan-sha.

Tokyo Koji-in. 2003 (orig. 1900-1906). Tokyo kojiin geppō [Monthly Report of Tokyo Orphanage]. Tokyo: Fuji Shuppan.

Tokyo Yōiku-in. 1953. Yōiku-in 80 nenshi [The 80 Year History of the Tokyo Metropolitan Orphanage]. Tokyo: Tokyo Yōiku-in.

Sawayama, Mikako. 2008. Edo no sute-go tachi : Sono shozō [“Thrown-Away” Children in Edo: Their Portraits]. Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kobun-kan.

Selden, Mark. 2009. “Forgotten Holocaust: U. S. Bombing Strategy, the Destruction of Japanese Cities, and the American Way of War From the Pacific War to Iraq.” In Bombing Civilians: A Twentieth-Century History, edited by Yuki Tanaka & Marilyn B. Young, pp. 77-96. NY: The New Press.

Takeda, Toshio. 1948. “Furōji no mondai” [The Problem of Juvenile Vagrants]. Shakai Jigyō 31: 1: 1-6.

Yoneda, Toshihiko. 2015. “Kūshū sokai kara mita sensō to kodomo” [The War and Children: The Impact of Fire Bombing and Evacuation]. Yōji Kyōiku-shi Kenkyū 10: 46 61.

Yoshioka, Genji. 1987. Yakeato shōnen-ki [My Childhood in the Ruins of Fire Bombing]. Tokyo: Chūō Kōron-sha.

Notes

In Japanese, sensō koji and sensai koji are used interchangeably. Yet, strictly speaking, they differ: sensō refers to the war while sensai refers to the damage caused by the war. In this text, I use sensō koji, as sensai refers to the consequences of the war.

Other categories of mukoku no tami are: kan (鰥) (widowers older than age 61), ka (寡) (widows older than age 61), doku (独) (those older than age 61 without children), rō (老) (those older than age 65) and shitsu (疾) (those who are disabled). According to Nomoto Sankichi, these categories were created in the seventh century (Nomoto 1998: 18).

During the feudal era (1600-1867), the common terms for “orphan” were minashi-go (身無子) and sute-go (捨て子). Minashi-go refers to children without parents or other caretakers. Sute-go is a compound word of the verb suteru (to throw away) and the noun ko or go (child). Sawayama Mikako argues that during the feudal era, some desperate parent(s) “threw away” their child in a place where he or she would be likely to be found, such as the temple compound on a festival day, or at the front gate of a notable family in their own neighborhood. Parents rarely discarded their newborn baby, fearing that the infant might die before being found. Those who practiced sute–go were mostly poor people, for whom illness, death, or divorce made it impossible to raise children (Sawayama 2008). The Meiji state changed the name sute-go to ki-ji, an abandoned child, and criminalized the act of “throwing away the child.”

Rikugō Zasshi (六合雑誌) is a journal published between 1880 and 1921 by a group of Protestant and Catholic writers. They aimed to propagate “the truth of Christianity” in Japan. Rikugō means “heaven and earth, and the four directions of east, west, south and north” or “the universe.”

By the end of the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895) and the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905), the number of orphanages in Japan had reached nearly 140. Nevertheless, the Tokyo Metropolitan Orphanage [Tokyo Yōiku-in], established by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government in 1872, was the sole public institution until 1945. All other orphanages were private institutions founded by Christians, Buddhists or lay people.

Tokyo Koji-in (Tokyo Orphanage), a private orphanage established in 1899, changed its name to Tokyo Ikusei-en in 1907. In 1910, only 32 out of 136 orphanages in Japan still bore the name koji-in. All others used either ikusei or ikuji, instead of koji. Both ikusei and ikuji mean “to rear a child.” By dropping koji and replacing it with a term that implies the value of orphans, orphanage founders tried to present their institutions as family, and themselves as “fathers” and “mothers” of the children.

The title of this article is: “Hitsū no unmei o hiraku: kokuji to shite yōiku” [Overcoming the Tragic Fate: We are determined to bring up our [orphaned] children as kokuji].

The battle of Okinawa, which formally ended on June 25, 1945, prior to Japan’s surrender, killed approximately one fourth of the island’s entire population, that is, about 190,000. Among them, more than 120,000 were Okinawan civilians. In his study of “war orphans” in Okinawa, Asai Haruo (2016) points out that there were no “orphanages” in Okinawa before the end of the war. Instead, the system of mutual help in each neighborhood took care of children who had lost their families. The war almost destroyed this system, as the U.S. military placed most of these children in refugee camps together with adults.

In this article, I exclude from the category of sensō koji the “mixed-blood” children, who were institutionalized in orphanages or other-state sponsored facilities in postwar Japan. Mixed-blood children were born of a Japanese mother and a foreign father stationed in Japan during occupation, between 1945 and 1952. The postwar Japanese government did not count the number of mixed-blood children, let alone the number of mixed-blood war orphans, until 1952. Hence, their number is not included in the figure of 123,511, counted in 1948. For more information about mixed-blood children, see Roebuck (2016) and Kanō (2007).

At the time of the March 10 bombing, one of Kaneda’s sisters was younger than 8 and another sister was older than 13.

The following example demonstrates the scale of karikomi. Between June 22 and July 10, 1946, 512 street children in Tokyo were “hunted,” “captured,” and brought to the Tokyo Metropolitan Orphanage. At the end of December 1946, this orphanage housed 928 such children (649 boys and 279 girls). More than 20 percent of them ran away from the orphanage within a few days of their arrival. (Tokyo Yôiku-in 1953: 272). I also note that by 1942, the number of privately-run orphanages had plummeted. The caretakers were increasingly mobilized as soldiers or laborers. Donations declined or stopped. Several orphanages were commandeered by the army, and many were eventually destroyed by U.S. bombing.

In the immediate postwar era, many street children were addicted to methamphetamine, commonly called hiropon. Hiropon, or Philopon, is the brand name of a methamphetamine manufactured by the Dai Nippon Pharmaceutical Company during the war, widely used by soldiers as a “stimulant” to fight. After the war, significant quantities of the drug ended up on the black market. The drug, having lost its original role, quickly spread among Japanese people in dire straits, including street youth (Aochi 1951).

Another example is a series of radio dramas titled Kane no naru oka [The Hill where the Sound of a Bell is Heard], which was broadcasted 615 times from July 5, 1947 to April 28, 1950. The protagonist was Kagami Shūhei, a demilitarized and repatriated soldier, who eventually succeeds in building a house for sensō koji-cum-furōji in Nagano, Aichi and Hokkaido prefectures. Other characters included a dozen or so sensō koji. Though some of them engaged in petty theft, all of them eventually understood their mission to build a new Japan (Henmi 2007).

As the largest reformatory remaining in the rubble of Tokyo, Hagiyama received much aid through Licensed Agencies for Relief in Asia (LARA). LARA was launched in June 1946, through thirteen Christian organizations based in the United States, and continued its activities until 1952. LARA’s main recipients were destitute people institutionalized in orphanages, shelters for children, hospitals for tuberculosis patients, shelters for homeless people, old people’s homes, and hospitals for leprosy patients. Children in schools in major cities, where the effects of the bombings were particularly severe, and homeless repatriates were also recipients of LARA’s aid (Kawasaki 2010: 122).

In early postwar Japan, it was quite common for sensō koji-cum-furōji to sneak onto the trains without buying tickets. While such an act was a crime, station employees seemed to have routinely allowed them to do so. Hence, many covered long distances in search of food, shelters and friends.

Nagata’s narratives were also recorded in the booklet titled Sensō koji tachi no hajimete no ibento kiroku-shū [Report of the First Event where War Orphans Spoke], edited by Sensō koji no kai (2009).

For the changing narratives of sensō koji, see “Sensō keiken” no sengo-shi: Katarareta taiken, shōgen, kioku [The Postwar History of the Narratives of Wartime Experiences: Experiences, Testimonies and Memories] by Narita Ryūichi (2010), and Sokai taiken no sengo bunka-shi [The Postwar Cultural History of the Experiences of Evacuation] by Lee Seungiun (李承俊) (2015: Chapter 2).