Yuki Miyamoto’s Japanese translation of the prologue is available below.

Abstract1

The fear of being forgotten that haunts the victims of the Fukushima nuclear disaster set in quickly in the months following March 11, 2011. The Tokyo Olympics, touted as the “Recovery Olympics,” has served as a powerful vehicle for accelerating amnesia, on the one hand justifying the rushed reopening of restricted zones and other decisions of convenience, on the other, programming moments highlighting Fukushima in the Games. As preparations for the latter, especially the torch relay, reached fever pitch, the novel coronavirus intervened to force an abrupt postponement. It also disrupted ongoing and special events planned for the ninth 3.11 anniversary. The essay below elaborates on that context as an introduction to two texts by Muto Ruiko, head of the citizens’ group whose efforts led to the only criminal trial to emerge from the Fukushima disaster. The first, a speech anticipating the torch relay, outlines what the Olympics asks us to forget about Fukushima; the second is a reflection on living under two emergency declarations, the first nuclear, the second, COVID-19.

Key words: Olympics; Fukushima; torch relay; COVID-19; coronavirus; Dentsu; activism; Muto Ruiko

Prologue from an Ever-Shifting Present

Everybody has experienced, from childhood on, time crawling and time galloping, or time simply standing still, against the indifferent tic-toc of the clock. For much of the world, there is now a recent remote past—before the pandemic—and a present of bottomless uncertainty. But time continues to move unevenly in the new present, marked by unpredictable drama, as in the case of a tweetstorm that forced Abe Shinzo’s government to shelve a bill extending the retirement age of prosecutors, or by unexpected power, as in the global fury unleashed by the murder of George Floyd at the hands of the Minneapolis police. The former, exploiting the attractive anonymity afforded by Twitter, punctuated years of quiescence following the demonstrations provoked by the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster, when tens of thousands of Japanese were willing to show their faces in protest. The latter seems the logical culmination of only the most recent instances of police brutality hurled before our eyes by the unabated racism and structural inequality prevailing in the U.S. Although the Japanese instance has been related to the coronavirus, the U.S. case is indisputably magnified by the overwhelming disparity in COVID-19 suffering, whether in numbers of death, the preponderance of minorities in the under-compensated, risk-burdened ranks of essential workers, and the economic nightmare, owing to job insecurity and paucity of savings, produced by the pandemic, such that “logical” now has the force of “inevitable.” And yet, is so remarkable as to also seem unpredictable.

As one recent remote past is replaced by another, we cannot forget that the issues thrust upon us by each of these recent pasts have hardly been resolved. Even as they momentarily recede from the foreground, they constitute a cumulative, living—and therefore, shifting—seismic force upon our present. This is the spirit motivating the following examination of the Tokyo Olympics and the Fukushima nuclear disaster, meant to serve as an introduction to two reflections by Muto Ruiko, head of the Complainants for the Criminal Prosecution of the Fukushima Nuclear Disaster. The first was delivered in anticipation of the 2020 Olympic torch relay to be kicked off in Fukushima; the second, written in the midst of the COVID-19 emergency declaration.

No time for Olympics: Azuma Sports Park, Fukushima City March 1, 2020. Source |

A Dream Vehicle for Amnesia

In the early spring months of 2020 in the northern hemisphere, the grim march of infection numbers was punctuated by reports of miraculous sightings, some true, others false: swans (false) and fish (true) in the lagoons of Venice; or blue sky in New Delhi. It felt as if decades of devoted action, joined in recent years by youth from the world over demanding that the earth be habitable for them, were being mocked. As if only a pandemic could bring about conditions seemingly more hospitable to life forms even as livelihood for many threatened to imperil health or simply vanish.2

In Japan, as if to scoff at the concerted efforts to protest that fabulous exercise in deceit called the “Recovery Olympics,” postponement of the games was abruptly announced on March 23, 2020, a scant four months in advance of the opening, when the torch—dubbed the “Flame of Recovery”—had already begun its triumphal progress3 in northern Japan. Does this mean that the effort expended in opposing the Olympics was wasted? The question is rhetorical, of course. In the coming months and years, we will need to reflect on the political, socioeconomic, and experiential impact of the assaults brought on by two kinds of invisible agents, radionuclides and a pandemic-causing virus. But for now, let us pause over the actions of antinuclear activists confronting the convergence of Covid-19 and the 2020 Summer Olympics and Paralympics.

There is nothing bold about claiming that a major design of the games was to put paid to the 2011 triple disaster, most especially, the nuclear disaster. That objective is trumpeted in the official moniker, the “Recovery Olympics” (or in the even less merchandise-friendly translation of fukko, “Reconstruction”). It is still worth remarking how quickly those wheels were set in motion—the goal announced and declared achieved in virtually the same breath, as in Prime Minister Abe’s “under control” statement before the International Olympics Committee in Buenos Aires, a claim at which even TEPCO would demur shortly after it was made. That was September 2013. But the domestic selection of Tokyo as Japan’s candidate city had taken place on July 16, 2011, an indecent four months after the terrifying explosions. Only one month earlier, the Japanese government had admitted to the International Atomic Energy Agency that the molten fuel in reactors 1-3 had suffered a “melt-through” and not a mere “meltdown.” The daunting physical trials posed by the Fukushima Daiichi plant generated correspondingly difficult administrative challenges for Kan Naoto’s Democratic Party government. In late April, University of Tokyo professor Kosako Toshiso, hitherto a reliable government expert testifying against A-bomb survivors pressing for recognition, resigned as special cabinet adviser in a tearful press conference: as a scholar and from the standpoint of his “own humanism,” he could not condone raising the annual exposure rate for workers from 100 millisieverts (mSv)/yr to 250, or from 1 mSv/yr to 20 for primary school playgrounds in Fukushima.4 How could anyone in a position of responsibility have had the spare time to be plotting an Olympic bid during that period?

“And in any case, I absolutely cannot inflict such a fate on my own children” Special cabinet adviser Kosako Toshiso announcing his resignation at press conference April 29, 2011. Source |

A quick review suggests it was more a case of who was sufficiently determined to press on with pre-existing ambitions in the face of a catastrophe. Right-wing, nationalist politician Ishihara Shintaro, then Governor of Tokyo, had felt thwarted by the loss of the 2016 games to Rio de Janeiro.5 With strong encouragement from former prime minister Mori Yoshio (who would become head of the 2020 organizing committee), Ishihara declared that Tokyo would bid again once he was reelected on April 11. On that same day, Matsui Kazumi, a Hiroshima mayoral candidate opposed to that city’s Olympic bid, was elected, and in short order, withdrew the city from the running, leaving Tokyo as the de facto candidate from Japan.6 Ishihara, speaking in Tokyo on July 16, 2011, “passionately” proclaimed the purpose of the “Recovery Olympics” (fukko gorin) to be the demonstration of Japan’s recovery from the 2011 disaster. By the end of 2011, a pet scheme opportunistically harnessed to the disaster by conservative politicians had won support across party lines. Noda Yoshihiko, who succeeded Kan as prime minister even or especially as the latter showed himself susceptible to public sentiment favoring de-nuclearization, declared that the Fukushima plant had successfully entered a “cold shutdown” on December 6. (See timeline here.)

Preparing for official 2020 Tokyo bid: Governor Ishihara Shintaro with Jacques Rogge, IOC chair July 2, 2011. Source |

With hindsight—and not much of that—it is easy to grasp that the disaster and the 2020 Games were a match made in Olympic heaven. Without this bit of serendipity, the 2020 bid might have floundered in search of a convincing brand. (The mission of the failed 2016 bid was “Uniting Our Worlds.”) In the coming months and years, one worthy goal or another was accentuated for Tokyo 2020, but Recovery has been the mainstay.7 The serendipity has proven to be priceless because the promotion-proclamation of recovery, regardless of cost to people, the environment, and even government credibility, was the guiding principle behind managing the disaster from the start, as reflected in the watchwords of “ties that bind” (kizuna), “recovery/reconstruction/revitalization” (fukko), and “reputational harm” (fuhyo higai). This triplet of key words—two carrots of hope, one stick of warning—has managed to police Fukushima discourse to the present day: who would resist the call for solidarity in the hope of recovery? Or impede recovery by expressing worries about food safety? The expression of anxiety, whether on the part of mothers who stayed on or Tokyo consumers, is susceptible to the charge of causing “reputational harm,” which can further be seen as participating in discrimination against Fukushima.8 Redefining evacuation zones, ever so narrowly defined from the start, along with assistance cutoff, began as early as September 30, 2011, well before the Olympics were secured, but convenient markers of recovery gained tacit and explicit reinforcement as soon as the Olympics appeared on the horizon.9

True to the adage that a good offense is the best defense, Fukushima itself was assigned a prominent role: to host the opening matches in baseball and softball, and perhaps even more significantly, to serve as the starting point of the torch relay.10 In other words, the intractable nuclear disaster, which had often taken a back seat to the earthquake and especially, the dramatic tsunami in invocations of the “triple” disaster, was to be featured front and center, albeit momentarily, in the form of its erasure: Fukushima would be displayed to the world as having recovered. And to further drive home the point, J-Village, the former national soccer training center that served as the frontline base for operations for Fukushima Daiichi (workers lodged, vehicles washed, protective gear donned and disposed of) from March 15, 2011, was selected for the start of the torch relay. Not surprisingly, despite extensive efforts to clean up and beautify—including having local elementary students planting grass seedlings—radioactive hot spots continue to turn up.11

Getting ready for the Olympics in Fukushima Children at work on turf seedlings at J-Village May 8, 2018. Source |

The Astonishing Journey of the Torch

By February, the crescendo of 2020 Olympics preparation in Fukushima took on a manic quality before descending into a surreal sublime and finally, sputtering into silence. Day one of the torch relay was to take runners through areas close to the plant. Futaba, one of two adjacent towns hosting the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station, its entire population still under mandatory evacuation, was not on the original route. With a partial lifting scheduled for March 4, the organizing committee decided on February 13 to respond to the wishes of the prefecture and rearranged the schedule to include Futaba. This would, said the grateful mayor, “light the flame of hope in our hearts and become a boost for recovery.” On March 14, the severed sections of the Joban train line that connected this portion of Fukushima with Tokyo were reconnected for the first time in nine years. Some gathered to cheer on the platforms, despite the fact that not much of the land beyond the station was accessible, for most of the town was still designated as “difficult-to-return-to” in the tactful—that is to say, strategically obfuscating—parlance of Fukushima disaster management.12 The plan was to have the flame, carried in a lantern and accompanied by runners, transported by train to newly reconstructed Futaba Station as part of the relay on March 26.

Back in the metropolitan region, in the meanwhile, the number of people aboard the Diamond Princess cruise ship docked in Yokohama testing positive for the novel coronavirus shot up from 10 to 700 between February 4 and 28. With the Abe regime clearly hell-bent on holding the Olympics as scheduled, local organizers scrambled to stay one step ahead of the virus. They could not bring themselves to relinquish plans for displaying the torch in the three disaster-hit prefectures prior to the relay, not to say the relay itself. Whatever the precautionary advice, nothing like social distancing was on display as people flocked to see the “Flame of Recovery” at its various resting places. Most provocative, though, was the flame’s journey on the local Sanriku Railway in Iwate Prefecture. Secured in a lantern, it was placed between facing seats before a window, through which the “coastal townscape of recovery proceeding apace spread before the eye.”13 Passengers had been excluded, but the lantern could be viewed at key stops, where people gathered to welcome and then send off the flame.

|

Lantern transported on Sanriku Railway from Miyako to Kamaishi, Iwate Prefecture March 22, 2020—two days before postponement announced. Source |

|

Lantern transported from Kamaishi to Hanamaki, Iwate Prefecture on SL Ginga [Milky Way], inspired by the work of Iwate-born writer Miyazawa Kenji March 22, 2020. Source |

|

Even as this frenzied prelude unfolded, anxiety mounted as to whether the torch relay itself could in fact take place. On March 17, it was announced that the relay would be held, but without the ceremonies planned at stopping points. Spectators would be permitted as long as they “avoided” overcrowding, though one resident expressed disappointment: she had thought “the sight of overflowing crowds would symbolize recovery.” In less than a week, on March 23, this plan was replaced by a new proposal: a torch relay with no spectators—and no runners. The flame would be driven around Fukushima Prefecture, stripped even of the romance of rail travel. The following day, however, the other shoe dropped: the Games were to be postponed until 2021, and the 2020 torch relay canceled altogether. Ever resilient, organizers put the flame on display at J-Village for a month beginning April 2, with the hope that it could tour other parts of the country in the interest of “revitalization.” This, too, came to naught within the space of one week, with the Prime Minister’s declaration of a state of emergency.14

It could be taken for parody, this frenzy over the torch relay. The Olympics were meant to be a magic wand waving a spanking new post-disaster world into existence. As those prospects began to dim, the flame burned ever more brightly. The fuel? Greed. Pride. A yearning for fantasy in the midst of a dubious recovery, and an appetite for exploiting it. And the apparent means to do so. Or deciding that the means existed, despite mounting cost overruns.15

Recently, it was reported that the Foreign Ministry was directing $22 million to AI monitoring of overseas coverage of Japan’s pandemic response—as if this were more a “PR challenge than a profound public health crisis” (Kingston 2020). Perhaps this mode is even more far-reaching than we cynically, or more neutrally, abstractly, imagine. About one year ago, Taakurataa, a remarkable little magazine published in Nagano Prefecture, managed, through tenacious use of Japan’s version of freedom-of-information requests, to discover that in the seven years between 2011 and 2018, the central government and Fukushima Prefecture had paid $224 million to the PR firm Dentsu. The Environment Ministry was by far the greatest customer, using approximately half that budget for Dentsu’s services in the campaign to inform the public about its decontamination and debris cleanup efforts. The guidelines were to make people feel “safe and secure” (anshin anzen) again, “bring people back to their home towns,” and “have citizens recover pride in their hometowns.” A study group was created, consisting of staff from the prefectural forestry and fishery division as well as newspaper and TV marketing divisions, not to purvey a message, but in order to monitor twitter users and identify those who could be classified as “sources of reputation harm,” “supporters of the right-to-evacuate trial,” or simply “noise,” if they said anything that would dampen enthusiasm for Fukushima agricultural products.16 It is hard to avoid the conclusion that a marketing firm had been appointed a principal actor, with potential censorship power, in deciding Fukushima policy. And of course, that same firm is a major player in Tokyo 2020: Dentsu Inc. is the Games’s official marketing agency.

A briefly revealed, quickly forgotten detail about the Olympics-Dentsu chain of operations makes Fukushima seem a minor, though useful, link in that chain: a former Dentsu executive and member of the organizing committee disclosed, a few days after postponement was announced, that he had played a key role in securing the support of an African Olympics power-broker now under investigation by French prosecutors. He, Takahashi Haruyuki—still on the organizing committee—had been paid $8.2 million by the Japanese bidding committee, which presumably had some relation to the $46,500 the bidding committee paid to Seiko Watch. Seiko watches and digital cameras, said Takahashi, were “cheap,” and common sense dictated that “You don’t go empty-handed.” Dentsu’s contracts for Fukushima recovery—as known to date—come to seem almost reasonable, at $224 million over seven years, or $32 million per year. Takahashi singly was paid one-quarter of that to procure the Recovery Olympics.

Perhaps this is all unsurprising—a version of normal operating procedure most of the time for certain strata of the world. If so, then here, as in countless other instances, we need to make the modest yet seemingly immense effort to refresh our capacity for surprise. And anger. That there is so much profit to be made in doing anything but genuinely contribute to Fukushima remediation, to in fact, profit by diverting attention and burying the disaster, as if “nothing had happened,”17 should rouse us all, in solidarity both with the few who sustain the struggle and with those who gave up long ago, too exhausted from maintaining daily life to keep insisting not only that something had happened, but that it was still happening. Some of the struggle-weary were likely in the throngs greeting the arrival of the flame from Greece, or taking selfies with the lantern-encased flame. And as astonishing as it seems, there is already a new generation of children who were infants or unborn in 2011 now grown old enough to enjoy a spectacle touting the recovery of their region, their pleasure untainted by responsible education about the long-term impact of a nuclear disaster.18 Their parents may have welcomed the chance to banish recurring reminders of the disaster: reports of the re-dispersal of radionuclides and especially conspicuous, images of decontamination waste bags unmoored in the flooding brought on by Typhoon Hagibis; or the agonizingly protracted, risky dismantling of a highly contaminated vent stack at the Fukushima Daiichi plant itself; or the Olympic plans themselves putting hot spots back in the news.19 Bread and circuses is the bright side of the coin whose other face is expert exhortation to accept living amid decontamination waste for the foreseeable future: “Why would other prefectures want to accept waste that you yourselves don’t want?”—exhortation sweetened by the assurance that Fukushima contamination is not, for the most part, harmful. Anxiety, after all, is a matter of the mind/spirit (fuan wa kokoro no mondai).20

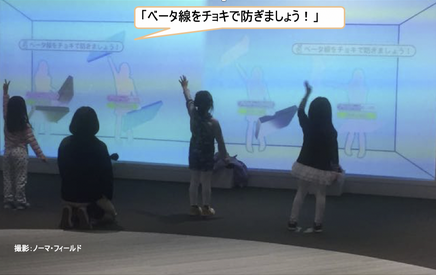

Radiation instruction for the very young: Radiation instruction for the very young: “Let’s block beta particles with ‘scissors’!” Fukushima Prefectural Centre for Environmental Creation, Community Relations Wing – July, 2018 |

It was back in June of 2019, an eternity before Covid-19 would appear on anybody’s horizon, that the torch relay route was announced, omitting Futaba. Was that omission owing to the last, frayed shred of realist perception, in view of the fact that the town was still off limits to the entire population? As Kowata Masumi, councilor of Okuma, the other town hosting the Fukushima Daiichi plant, and one of the painfully few elected officials in Fukushima willing to address radioactive contamination, observed, “National Route 6 still has high radiation levels. There are places where hardly any residents have returned, and conditions are not suitable for people running or cheering from the roadside.” Voicing the common complaint that the Olympics were deflecting workers and materials from Fukushima, she told Our Planet-TV, “They seem to have turned the idea of recovery on its head.” Any legitimacy accruing to the commonsensical had long ago been extinguished in the fever dream of the Olympics.

Protest and Pandemic

“It’s all Olympics all the time,” said emails from Fukushima. But as February wore on, with the drumbeat of news from the Diamond Princess cruise ship, the novel coronavirus became an ominous competitor for attention. Emails began to say, “It’s exactly the same. Deny it’s happening. Don’t test. Find experts who’ll support that policy.” And rather sooner than later, “Is anyone taking responsibility?”21 If COVID-19 cast a shadow on Olympic plans, it also was a challenge for groups long opposed to the games. This was the run-up period for the 9th anniversary of March 11, a difficult time for survivors and a crucial occasion for them and antinuclear activists to remind the rest of the country of what had happened and how much remained unresolved, with some hardships predictably aggravated, rather than alleviated, through the passage of time. Anguished discussions took place about canceling or proceeding with activities that had already consumed months of painstaking preparation. Sharing with other progressives a deep-seated antagonism to the Abe administration, activists were reluctant to relinquish the platform of the anniversary occasion, given already fading public interest exacerbated by the Olympics. Wouldn’t cancellation have a ripple effect on other organizations? Wouldn’t the government exploit this to apply pressure for “voluntary restraint” (jishuku)22 across a range of activities? At the same time, wasn’t the desire to safeguard health at the heart of the antinuclear movement? Was it appropriate for those who had made the agonizing choice to leave, not just Fukushima and immediately adjacent areas but the Tokyo region as well, to put themselves along with others at risk of exposure? If a valued keynote speaker were willing to appear remotely, were the organizers obliged to follow through? What were the ethics of putting one’s body on the line in these circumstances?23

Anniversary events, large and small, were postponed or canceled outright. One of the largest had been planned by FoE Japan (Friends of the Earth). Although not exclusively dedicated to the nuclear issue, it has been a leader in the field since 2011, remarkable for the depth of on-the-ground work underlying its educational and watchdog activities. Besides issuing its own carefully researched public comments, FoE has taken initiative to hold public-comment writing workshops, so that citizens unaccustomed to expressing themselves in this medium—never mind on such topics as evaluation of the Rokkasho reprocessing facility or the release of contaminated water into the Pacific—could be empowered to participate. In 2019, it launched an ambitious “Make Seeable” (mieruka) project to contest the Olympics-accelerated obliteration of traces of the disaster, whether the number and circumstances of evacuees, the disposition of contaminated soil issuing from “decontamination,” or health effects. The March 2020 symposium would have brought together workers from Fukushima, a liquidator from Chernobyl, evacuees, physicians and scholars, a physician and energy specialists from Germany, for presentations in Tokyo followed by two venues in Fukushima.24 In April, as part of the “Make Seeable” project, FoE Japan planned to send young people to a workshop in Germany where they could network with youth from France and Belarus as well as Germany. This, too, was not to be. Here, as elsewhere in the world, the novel coronavirus, itself as invisible as radionuclides, asserted its power in unmistakably visible fashion—revealing what had been obscured and providing opportunities for new concealment in the process.

The days of “voluntary restraint” from activity, without economic support to speak of, have imposed hardships, predictably severe for the most vulnerable. They have also intensified antinuclear activists’ sense of urgency: not only have they witnessed the power of the coronavirus to swiftly and therefore visibly impact all sectors of society, but they soon came to realize that it provided cover to proceed with activities they strenuously opposed, such as paving the way for dumping “treated” water from the damaged reactors into the Pacific.25 On another front, court dates for the approximately thirty Fukushima-related cases winding their way through jurisdictions around the country have been postponed or even cancelled, eliminating a precious occasion for plaintiffs, lawyers, and citizen supporters to rally at the courthouse and hold press conferences—for themselves, for all of us who should care, and for the judges, who need to know that there is still a caring public. One of the most active and inclusive groups of plaintiffs (both mandatory and “voluntary” evacuees, from within and without Fukushima) seeking compensation, their attorneys, and supporters centered in the Osaka area put together a composite video message to fill the lacuna, reminding us of their goals—securing normal lives, the right to evacuate, and a safe future—and giving us a glimpse of how nuclear evacuees are experiencing the coronavirus. The video format also reveals the still differing degrees of visibility participants feel able to tolerate—from full face, full name to full face but first/assumed name only to voice only.

With the pressure of the Olympics removed for the moment,26 these groups are having to grapple with the coronavirus as they continue to address the consequences of the nuclear disaster.

From Olympics to Pandemic: Two texts by Muto Ruiko

Muto Ruiko, who was propelled to antinuclear activism by the Chernobyl disaster of 1986, captured the nation’s attention with a breathtaking speech at the first “Sayonara Nukes” rally in Tokyo in September of 2011.27 She became head of the Complainants for Criminal Prosecution of the Fukushima Nuclear Disaster, which, against all odds, led to the only criminal proceeding—against three former TEPCO executives—to result from the disaster.28 She is a respected leader, vital to many of the activities referred to above and more. The first text below, “Fukushima ain’t got the time for Olympic Games” is a speech delivered at Azuma Sports Park in Fukushima City on March 1, 2020, just as storm clouds were gathering for the Olympics-pandemic collision. It was an action jointly organized by Hidanren—Fukushima Gempatsu Jiko Higaisha Dantai Renrakukai (Liaison of Fukushima Nuclear Accident Victims’ Groups) and Datsugempatsu Fukushima Nettowaku (Fukushima Denuclearization Network). It is translated here with permission from Muto Ruiko; the original may be found here. The second is a reflection from May on the two overlapping emergency declarations: the nuclear emergency, issued March 11, 2011, at 19:03 and as yet unrescinded;29 and the novel coronavirus emergency, declared on April 7, 2020, and rescinded in stages, by locale and region, between May 14 and May 25, 2020. The second piece was written before the coronavirus emergency declaration was lifted, for the newsletter of Tomeyo! Tokai Daini Gempatsu Shutoken Renrakukai (Shut it down! Liaison of Citizens from the Metropolitan Prefectures Seeking to Close Unit 2 of the Tokai Nuclear Power Plant).30 The piece, from Nyusu No. 4 (June 2020) is translated here with their permission.

|

|

Fukushima Ain’t Got the Time for Olympic Games

With the risks of the coronavirus in mind, we went back-and-forth about whether to proceed with this action, but considering that it would take place outdoors, that it wouldn’t involve large numbers, and that we would be equipped with face masks and alcohol, we managed to arrive at the decision to go through with our plans.

Nine years since the nuclear accident, the Olympics and the torch relay now dominate the news and the whole atmosphere of Fukushima Prefecture.

Night and day, athletes are giving their all to prepare for the Olympics.

Middle-schoolers have hitched their dreams to the torch relay and are eager to run.

And probably, there are people looking forward to watching the relay and the ball games.

Then why must we take this kind of action?

Because we think this is no time to be hosting an Olympics in Fukushima.

Have on-site conditions been stabilized since the accident?

Is the contaminated water under control?

How many workers have had to climb the vent stack to dismantle it?

Have victims been properly compensated?

Have their lives been restored?

Has industry returned to pre-accident levels?

Will these Olympics truly contribute to recovery?

Is it certain that neither athletes nor residents will be subject to radiation exposure?

With problems piling up one after the other, the people of Fukushima, both the ones living here and the ones who’ve left, are desperately trying to live their lives.

There isn’t a single person who doesn’t wish for a true recovery from the disaster.

In Fukushima today, what is it that we should be prioritizing first and foremost?

Stupendous sums of money are being poured into the Olympics and the torch relay. Multiple problems, hidden by the Olympics, are receding from view. We are worried about what will be left once the Olympics are finished.

It’s not the Fukushima that looks recovered on the surface that we want to make known. It’s the true conditions we want the world to know, about the cumulative problems that can’t be solved in nine short years—the suffering and the struggle caused by the harms of the nuclear disaster.

Then let us today, all together, proclaim heartily, “Fukushima ain’t got the time for Olympic Games!”

Life Under Two Emergency Declarations

In Fukushima, the “declaration of a state of emergency” issued with the spread of the novel coronavirus was superimposed on a “declaration of a nuclear emergency situation” that has never been rescinded. For victims of the nuclear accident, this occasion calls up many memories of that experience: staying indoors; wearing a mask; searching frantically for information; fighting the mounting tide of anxiety. In the early days of the contagion, we felt terribly oppressed, psychologically.

But gradually, it became possible to see that there were commonalities and differences between the nuclear accident and the spread of the coronavirus. Fearing that people would panic, the government concealed the truth. It limited testing as much as possible, and without disclosing accurate case numbers, made them seem trivial. Ad hoc measures led to the sacrifice of the most vulnerable. Expert opinion was distorted to suit political power. Taking advantage of the disaster, opportunistic capitalist ventures rose to press their interests. These are some of the commonalities.

Some of the differences are the speed with which the infection has spread, making it more readily graspable; the dispersal of the afflicted in large numbers throughout Japan; and large-scale citizen protest prompted by the government’s coercive actions with little regard for laws and statutory authority, such as the sudden request for school closures or the proposal for revision of the Public Prosecutor’s Office Act.

After the nuclear accident, we anticipated a transformation in values, in worldview. It turns out that such a wish is not readily granted. Maybe this time—we can’t help hoping. But, in a world where more chemical substances are added to the environment by the day, where climate change is intensifying, it is possible that the next emergency is already waiting in the wings. Rather than tossing and turning between hope and despair, we need to work hard, together, to gain clarity on what we should prioritize for protection in the event of such an emergency. Otherwise, we run the risk of letting our fear and sense of oppression invite the heavy hand of authority.

Eventually, the state of emergency occasioned by the coronavirus threat is likely be lifted, although questions about appropriateness of timing and extent will remain. But how long will the “declaration of a nuclear emergency situation” remain in effect, imposing on people annual exposure levels up to 20 millisieverts per year, or leaving behind waste with levels of radioactivity 80 times pre-disaster levels? In the shadow of the coronavirus, problems that demand resolution are accumulating, while opportunistic measures are advanced, such as the use of the torch relay to trumpet Fukushima recovery, or the release of contaminated-ALPS-treated water into the environment.

Living under a double state of emergency, I have come to hold, more than ever, that we must commit ourselves in earnest to the following simple task: “to learn the truth and to help each other.” Failing that, it will be difficult for us humans, along with other living things, to survive on this planet.

March 1, 2020. Source

***

あすになっても変わらぬ事実:『福島はオリンピックどこでねぇ』

原発災害と新型コロナ

ノーマ・フィールド

宮本ゆき訳

はじめに

概要:自分たちは忘れられてしまったのではないか、という思いは2011年3月11日以降、間髪おかず福島の原発災害を被った人たちの間に湧き上がった感情である。「復興オリンピック」と銘打たれた東京オリンピックは、被災に関する忘却を担う強力な装置の一環ともなっている。つまりオリンピックは、一方で避難指示の解除やそれに伴う「都合の良い」政策の決定を急がせ、他方、福島の「復興」を目立たせる計画を織り込めるのだ。得にその準備としての聖火リレーは熱狂的に迎えられたものの、新型コロナにより突然延期となった。同時に3.11の9周年を祈念する様々な行事も変更を余儀なくされた。以下のエッセイは、こうした背景を説明する傍ら、唯一東電の責任者を刑事告訴まで持ち込んだ市民グループを率いる武藤類子氏による「挨拶」として発表された二作品を紹介するためのものである。一作目は、聖火リレーが予定されるなか、いかにして人々が福島の原発事故を忘れるように仕向けられているかについて。そして二作目は二回に亘る緊急宣言―一度目は放射能により、二度目は新型コロナウィルスにより―の下での生活を振り返るものとなっている。

キーワード:オリンピック、福島、聖火リレー、新型コロナ、ウィルス、電通、アクティビズム、武藤類子

絶え間なく移ろう現在からのプロローグ

時計はいつも一定のリズムで時を刻んでいる。しかし、時間というものが、ときには

駆け足で迫り寄ったかと思うと、ときに止まってしまったかのように感じることは、子どものころから誰しも体験していることだろう。今や、世界中の多くの場所で、コロナ禍以前の生活が遠い過去のように思え、現在の不確かさは底なしのように思える。そして今、「時」というものが不均衡に進むなか、新しい現象が予想もしなかったような劇的な出来事として刻まれてもいる。例えば、安倍晋三率いる政府が提出した、とある検事の定年退職を延期する法案を世論が抑え込んだこと。 あるいは、ミネアポリスの警察により殺されたジョージ・フロイドに端を発する世界的な人種差別への怒り。前者は2011年の福島原発災害後、何万人もの日本人が顔を出したデモがあったものの、その後抗議活動が沈静化してしまったように見受けられたが、ツイッターの匿名性を利用することで再び盛り上がった事例であり、後者はアメリカに蔓延し、衰えることのない人種差別と制度的不平等の当然の帰結といえる。前者は新型コロナでの外出自粛に起因するともいわれているが、アメリカの場合は間違いなく感染拡大により、更に可視化された圧倒的な格差も要因である。アメリカの運動は、つまるところ感染による死者数であったり、エッセンシャル・ワーカーと呼ばれるリスクの大きい仕事に従事せざるを得なかったり、不安定な仕事で貯金もままならないことなどで経済的に窮地に追い込まれるといった様々な「原因」がいまや「当然の帰結」として現れた、ということだ。しかし、「当然」とは起きてから言えることで、当時はこの怒りのうねりはあまりにも大きく、予測できなかったのが真実だ。

一つの出来事が、新たな出来事で次々と塗り替えられていく昨今だが、こうした私たちを揺り動かした諸々の出来事の根底にある問題は解決されていない、ということを忘れるわけにはいかない。一瞬、表舞台から遠ざかって見える課題も、実際には、積み重なり、生きていて変化し続けている、地表からは見えない、いつか地震として現れ得るエネルギーのように、私たちの現在に働きかけているからだ。この文章は、福島原発告訴団を率いる武藤類子氏による二作の挨拶文を紹介するものだが、2020年に予定されていた東京オリンピックと福島の核災害との関連を検証することを旨としている。武藤氏の最初の文章はオリンピック聖火が福島を出発地とすることに対して書かれたもので、2作目は新型コロナによる緊急宣言を受けて書かれたものである。

忘却へのいざない

2020年春の初旬、北半球で新型コロナの感染者数が話題になると同時に、真偽の入り交じったニュースがSNS上で交錯し始めた。ベニスの運河に白鳥が戻ってきたという虚像のニュースから、浅瀬に魚の姿がはっきり見える画像や、ニューデリーの澄んだ空の画像(後者はともに真実)などだ。これは、地球は自分たちの住処だから、と環境汚染に警鐘を鳴らしてきた世界中の若者たちの努力をあざ笑っているかのようにも見えた。多くの人が生活を維持するため自らを感染の危険にさらし、あるいは仕事を失う危機に直面している時に、あたかも感染症のみが地球上の生命に優しい環境をもたらせ得るかのように。

一方、日本では「復興オリンピック」などというまやかしのネーミングに対する抗議活動を一蹴するかのように、突然、開催4ヶ月前の2020年3月23日になって大会の延期が発表された。その時「復興の炎」と名付けられた聖火は、すでに勝ち誇ったようにその歩を東北地方に進めていた。ここでオリンピックに反対する運動は無駄だったと解すべきだろうか?もちろん、これは反語だ。これから来たるべき将来に向けて、私たちは二種の可視化できないもの―放射性物質と世界的に感染を引き起こしているウィルスと—が私たちの政治的、社会的、経済的、そして経験にもたらすであろう影響をしっかり考えていかなければならない。ここではひとまず、反核の活動家が新型コロナウィルスと今年予定されていたオリンピック、パラリンピックで直面したことについて考えを馳せよう。

オリンピックは2011年の地震・津波・原発のメルトダウンの三重の被害―得に原発災害―のイメージを払拭するために使われている、という考えに大方異論はないだろう。オリンピックは「復興オリンピック」(英語ではリカバリー・オリンピック、あるいはさらに冴えない売り物になりにくいリコンストラクション・オリンピックと呼ばれる)と公式に名付けられ、その目的となる「復興」が高々と謳われてきた。安倍首相がブエノス・アイレスの国際オリンピック委員会で、福島は「アンダーコントロール」と宣言したこと(これは東電でさえ宣言後に難色を示したが)などを通して「復興」とオリンピックとの結びつきが素早く軌道に乗ったことは強調しておかねばならない。そして、東京でオリンピックを、という決断はすでに2011年の7月16日、つまりメルトダウンのほんの4ヶ月後になされていた。このタイミングは、日本政府が「福島第一原発の原子炉1号機から3号機は単なる燃料溶解(メルトダウン)ではなく、燃料が溶け落ちた(メルト・スルー)」とする見解を国際原子力委員会に対し認めたわずか一ヶ月後だった。

当時、福島第一原子力発電所はその惨状を露呈しており、これは民主党を率いる菅直人(当時)首相にとって深刻な課題だったことは言うまでもない。その年の4月、原子力を専門とする東京大学大学院の小佐古敏荘教授から記者会見で衝撃的な発言があった。その時点まで広島・長崎の被ばく者裁判で、被ばく者の主張に否定的で、政府にとって信頼のおける専門家の一人だった彼が、記者会見で涙を浮かべながら、政府の特別顧問を退任することを発表した。彼の退任は、科学者として、そして彼自身の「ヒューマニズム」の観点から、作業員の年間被ばく許容量を100ミリシーベルトから250に引き上げること、また福島の学校の運動場でさえ1ミリシーベルトから20ミリシーベルトに引き上げることは受け入れがたいことからだった。こうした議論の最中、責任ある立場の人間がオリンピック誘致について考えを巡らせる余裕があったことを、どう考えたらよいのだろうか?

少し調べてみると分かることだが、未曾有の災害に面しつつも、以前からあったオリンピック開催という野望を推進しようとした人物がいた。それは、右派ナショナリスト、当時の東京都知事・石原慎太郎だ。彼は2016年のオリンピック開催地の選出でリオ・デ・ジャネイロに敗れたことに未練があり、2011年4月11日に都知事として再選されるやいなや、前首相の森喜朗の強い薦めで(森は2020年オリンピック・パラリンピック協議大会組織委員会の会長の座に就任)もう一度オリンピック開催地として東京都が立候補することを公言した。同日、広島でオリンピックを、という公約に反対表明していた候補者の松井一実が広島市長に当選し、即刻広島の候補地辞退に着手。これにより、東京が日本における唯一の候補地となった。2011年7月16日、石原は「復興五輪」は日本が2011年の災害から回復したことを示すことになる、と力を込めて宣言した。

こうした保守政治家による災害に便乗したプロジェクトは、2011年の年末までに、党派を超えて支持を集めたのだった。脱原発の世論に耳を傾けるようになっていた菅首相の後を継いだ野田佳彦首相はなんと12月6日、福島第一原発は「冷温停止」の状態に入ったと宣言した。

今から省みると、災害と2020年のオリンピックは「五輪の神の采配」で結び付けられたかのようにさえ思える。というのも、こうした偶然がなければ2020年の開催地を決めるプロセスで東京(日本)を魅力的な候補地として紹介する要因を探すのに苦戦していたはずだ。(2016年に落選した際のスローガンは「世界を一つに」)。落選後、再度東京オリンピックの目標を示す幾つかの標語が提示されたが、言うまでもなく「復興」はその中心だった。「復興」がオリンピックとセットになったとき、人がそこに暮らし続け、海外からの訪問客を迎えるのに安全な地となることが目標として掲げられ、同時に、それがすでに達成された状態であるかのように機能した。暮らし、環境、そして政府に対する国民の信頼までも容赦なく犠牲にし、目標であるはずの「復興」がその達成と巧妙に重ねられ、災害対策の中心に当初から据えられてきた。例えば、それは「絆」、「復興」、あるいは「風評被害」といった言葉に表されている。この三つのキーワードはアメとムチとなり(二つの希望的アメと一つの警告的ムチ)今日に至るまで、福島に関する都合の悪い世論を押さえ込んできた。「復興を願って団結しよう!」という呼びかけに対し、誰が反対できるだろうか?食の安全に関する不安を吐露することが復興を妨げたると言われれば、誰がその不安を口にできるだろうか?不安を表明することは、それが福島に残った母親であれ、東京の消費者であれ、風評被害を呼び込むことだという非難を覚悟しなければならず、またそれは福島の人たちへの差別を助長することだと見られてしまうのだ。もともと過小に設定されていた避難区域はさらに縮小され、補助金の打ち切りは、東京がオリンピック開催地として選ばれるはるか以前の2011年の9月には始まっていた。様々な復興指標は、オリンピック開催国の可能性が見えてくるやいなや、表舞台に登場することとなった。

「攻撃は最大の防御なり」のことわざが示す通り、オリンピックにより福島は特別の使命を与えられた。野球とソフトボールの開催試合が彼の地で開かれることとなった。さらに重要なことは聖火リレーの出発地となったことだろう。「震災」や「津波」の影に追いやられがちな制御不能な原発事故が、その痕跡の消去という形で一瞬とはいえ表舞台に踊り出た。これは「福島は復活した」ということを可視化することでもあった。更に言えば、2011年3月15日以降、事故後の福島第一原発における最前線基地と(作業員の宿泊施設でもあり、作業車の洗浄、防護服の装着所や使用後の廃棄処分場として活用)されていた元国立サッカー・トレーニング・センターだったJヴィレッジが聖火リレーの出発地として選出されたのだ。集中的に行われた除染と美化―そこでは地元の小学生が芝生を植えることさえあった―にもかかわらず、放射能のホットスポットが相変わらず見つかっていることは、驚くべきことではないだろう。

聖火の驚くべき行程

福島におけるオリンピック準備は、熱狂的なお祭り騒ぎとして始まり今年の2月まで加速し続けたが、最終的には線香花火のようにパチパチとはぜて消えてしまった。聖火リレーの初日は福島第一原発所近辺を走ることになっていたが、施設の一部が立地する双葉町(全町が帰還困難区域)は当初リレールートには入っていなかった。双葉町の一部が3月4日に非難解除になることを受けて、オリンピック組織委員会は2月13日、県の要望を受けた形で双葉町をリレールートに入れるよう変更した。これに関し伊沢史郎双葉町町長は、感謝の念を表しつつ「心に希望の光をともし、町の復興を後押しする機会」と発言。そして3月14日には、震災以来断絶していた常磐線が復旧し、東京とこの地域が9年ぶりに再び線路で繋がれた。この機会を歓喜した人々がプラットフォームに集まったが、実際には駅以外の場所は「帰還困難区域」に指定されており、まだ立入禁止状態なのだ。(「帰還困難区域」といったような歯切れの悪いお役所言葉も災害に対する認識を管理する戦略と解すべきだろう。)計画によれば、3月26日にランタンで運ばれた聖火が電車に乗せられ、新しく建設された双葉駅に到着することになっていた。

その頃、東京近郊の横浜港に停泊していたクルーズ船ダイアモンド・プリンセス号の乗船客の多くがコロナウィルスの陽性反応を示していた。その数は2月4日から28日の間に10名から700名にまで登った。安倍政権がなんとしてもオリンピックを予定通り開催しようとしていることから、地元当局は何とかウィルスの先手を打っていた。オリンピック推進派にとって、被災地に聖火を運ぶ計画を中止にするわけにはいかず、ましてやリレーそのものを中止にするわけにはいかなかったからだ。どんな指導があったかは不明だが、「復興の炎」を一目見ようと、各地に集った見物客が感染を抑え込むために提唱されるソーシャル・ディスタンスを守ろうとする様子は見受けられなかった。最も驚かされたのは、岩手県の地元を走る三陸鉄道が聖火を運んだ際、ランタンで守られた炎は向かいあった席の間の窓際に置かれ、車窓には復興が進む沿岸部の町並みが広がった、とあたかも聖火の視点で復興を確認するような報道だった。乗客が一人もいない車内に、ランタンだけが主要な停車地点から見えるよう配置され、人々は駅舎からランタンの炎を迎え入れ、また送るために集った。天皇の行幸さながらの場面を繰り広げていた。

こうした熱狂の前奏曲が奏でられる一方で、聖火リレーが実際に行われるのかどうかといった不安も次第に高まっていた。3月17日、リレーは実施されるものの、休息地点でのセレモニーは取りやめ、という発表があり、沿道の観客は密集しなければよし、とされた。ある住人は「聖火のルートに大勢の町民があふれる光景が、復興を象徴すると思っていたが、この状況では仕方ない」と残念がった。それから一週間も経たない3月23日、この計画は、聖火リレーに観客は参加しない、そして走者さえも参加しない、とする新しいものに差し替えられた。聖火は福島県内を車で運ばれることとなり、鉄道の旅というロマンすら剥ぎ取られることとなった。そして翌日、恐れていたことが起こる。それはオリンピックそのものが2021年へ延期されるという発表だった。これにより2020年の聖火リレーはすべて中止が決定。それでも屈しない委員会のメンバーは4月2日から一月間、聖火をJヴィレッジに展示することを決め、更に他の地域へも聖火を巡回することで地方の再生につながることを期待した。しかし、一週間も経たないうちに、安倍首相が非常事態宣言を出し、この願いも潰えた。

こうした聖火に対する熱量はパロディーではないか、と疑うほどだ。オリンピックは魔法の杖、その一振りで、新しい震災後の世界が立ち現れる、といった風に。現実には、こうした願いが徐々にしぼんでいく一方で、聖火は今までになく明るく輝くようにみえた。その燃料は?「欲」と「プライド」。復興の名のもとで疑惑が満載ななか、ファンタジーの世界を求める欲求と、それをとことん利用しようとする欲望。それを可能にする財力。あるいは、とうに予算を超過しているオリンピックであるにもかかわらず、資金はまだ調達可能、という判断。

最近、外務省が日本の新型コロナに対する海外での反応を監視する人工知能に24億円を計上した、というニュースが報道された。それはまるでコロナ禍が「深刻な公衆衛生上の危機というよりも、PR作戦にとっての課題」として理解されているようだ。恐らく、こうした取り組みは、私たちが皮肉を込めて、あるいは常日頃漠然と想像するよりもずっと広く現実に浸透しているのかも知れない。長野県で出版されている「たぁくらたぁ」という素晴らしい月刊誌が、根気よく情報開示請求を繰り返したことで、2011年から2018年の7年間の間に、国と福島県が広告会社「電通」に248億円も支払っていたことが突き止められた。なかでも環境省は一番のお得意さまで、電通に支払われた総額のほぼ半分にあたる額を負担し、除染や瓦礫除去よりも、その努力を「伝えること」に費やしていることがわかる。そこでの方針は、人々の暮らしの「安心・安全を取り戻す」こと、人々が「地域の住民としての誇りを取り戻」し、「ふるさとから離れて暮らしている住民の帰還を促すこと」だった。福島県では、県の農林水産課の職員、新聞やテレビのマーケティング課の社員からなる勉強会が開かれているが、この会は有益な情報を提供する性質のものではなく、ツイッターなどの使用者を「風評被害元」「集団疎開裁判応援」あるいは単に「ノイズ」などに分類し、探り当て、それらの人々が福島の農産物の印象を貶めるようなことを言っていないか監視するためのものだった。こうして見ていくと、福島に関する政策決定で、広告会社が重要な役を担っていること、しかも恐らく検閲さえも任されていることは否定し難い。そして、もちろん同じ会社である電通が2020年の東京オリンピック招致にも公式の広告会社として陰に陽に大活躍していることも明記しておこう。

一部しか把握できていないながら福島関連の電通への膨大な支出額は、オリンピック招致のための出費と比べると、ほとんどささやかに見えてくるのも皮肉なことだ。それを物語るあるエピソードをあげよう。オリンピック延期発表の数日後、フランス当局の調べを受けているセネガル人で世界陸連前会長のラミン・ディアクがオリンピック委員会会員からの支持を取り付けるために金品を受け取ったことが明らかにされた。それを明かしたのは元電通専務(当時は顧問)東京オリンピック・パラリンピック組織委員会の会員・高橋治之(現在も組織委員会の会員)で、招致委員会から約9億円支払らわれており、そのうち5千万円以上、セイコーに費やされた可能性がある。高橋は、セイコーの時計やデジタルカメラは「安い買い物」で、「取引先に、手ぶらでは行けない。それは常識だ」と言っている。福島復興に関する電通との契約は、分かっている限り7年間で248億円、年間約35億となる。これは復興オリンピックを実現させるため、費用の四分の一の額が高橋一人に支払われた計算だ。

私たちはこうした話題に驚かなくなっているかも知れない。一定の階層にとっては常識であり、これこそが世間というもの。しかし、仮にそうだとしても、私たちは、簡単に見えて実際には相当の努力を要する「驚く」という感覚を大切にしなければならない。そしてそれに伴う怒りも。福島の状況改善に対して実際に貢献することのないまま巨額の利益が生まれ、その利益は本来注がれるべきところへの注意をそらし、災害を意識の底に埋もれさせていく。まるで「何事もなかった」かのように事態を取り仕切ることで利益を生み出す、という事実に私たちは奮い立たたなければならない。それは、まだ闘いを諦めていない少数派と連帯することであり、同時に、日々の暮らしが精一杯で、「何かが起き」、実際、「いまも起きている」という意識を持ち続けるには疲れ果ててしまった人たちに心を寄せることでもある。こうした戦いに疲れた人たちがギリシャから来た聖火のお迎えに出向き、ランタンに入った聖火と一緒に自撮りをしているのかもしれない。そして、2011年時点ではまだ生まれていなかったり、幼児であったりした世代が、地域の復興の一貫でこうしたイベントが浴びる脚光を享受し楽しんでいるとすれば、その理由は核災害の長期に亘る影響についてきちんとした教育が施されていないからに他ならない。一方、大人たちにしてみれば、災害を思い出させるもの―2019年の台風19号で放射性物質を含む除染土が詰められたフレコンバックが流されてしまった光景光景、福島第一原発で汚染のひどい排気筒のはらはらさせる解体作業、あるいはオリンピック企画自体によって発覚するホットスポット―を一瞬たりとも意識から遠ざけることができるものとして、このようなイベントは歓迎されるのかも知れない。

しかし、こうした「パンとサーカス」の仕組みは、一つのコインの明るい一面に過ぎず、同じコインの裏面には「見渡す限りの除染で出た廃棄物と共に暮らすことを覚悟せよ」という専門家による薦めが刻まれている。自分たちが嫌なものを他県で処分してもらうという考えは他県には到底受け入れられないという諦めと、根本には福島の汚染はほぼ健康に影響はない、という甘言に支えられ、「不安はこころの問題」として片付けられる。

去年(2019年)の6月、新型コロナが皆の意識にのぼるずっと以前に、双葉町を除いた聖火の行程が発表された。当時双葉町の除外は、この町が未だ立ち入り禁止区域であるという現実を見据えた最後の常識的見解だったのだろうか?双葉町とともに福島原発の立地である大熊町の木幡ますみ町議員は、福島で放射能汚染の話題に触れる数少ない議員の一人だ。木幡町議は「国道6号線の放射線量はまだ高い。住民がほとんど帰還していない地域もあり、人が走り住民が応援できる環境ではない」と話す。彼女はオリンピックが復興に必要な作業員や資材を福島から奪うことになり、それは「復興の意味を履きちがえている」とOur Planet-TVで発言している。しかしながら、こうした常識に基づく判断というものはオリンピック熱に浮かされ消えてしまったようだ。

抗議活動とパンデミック

福島から来るEメールには「オリンピックのことばかり」とあったものだが、2月になるとダイアモンド・プリンセス号からのニュースがどんどん入って来て、新型コロナウィルスが皆の注意を奪う不吉な競争相手となった。メールに書かれているのは「これは(福島事故の時と)全く同じ。起きていることを否定する。検査をしない。国の政策を支持する専門家を探し出す。」そして、かなり早い時期に、「誰か責任を取るのだろうか?」(原発と同じように取らないだろう)と。新型コロナがオリンピックの計画に影を落としているならば、この感染症は同時にオリンピックに反対し続けてきた人たちにとっても試練となった。ちょうど9年目の3月11日を迎える時期は、例年のことだが、被災者の人たちにとっては苦しい時期でもある。被災者と脱原発を支持する者にとって、原発事故を想起させるだけでなく、どれほどのことが未解決のままか、時の経過により苦難は軽くなるどころか予期されていたけれど実際より厳しくなっていることを再確認する重要なときでもあった。何ヶ月もかけて苦労して用意してきたイベントを中止にするべきか、続けるべきか、苦悩に満ちた話合いが行われた。多くの進歩的な人々同様、安倍政権への根強い反対を共有している脱原発の人びとは、オリンピックによってすでに人々の関心が福島から奪われてしまっていることから、3月11日の記念日に際してのイベントを中止することには消極的だった。催しを諦めることは他のグループにも波及効果をもたらすことになるのではないだろうか、政府はこの機会を悪用して(脱原発などの集会を)「自粛」するよう圧力をかけてくるのではないだろうか、といった懸念と同時に、そもそも命を守る願いありきの脱原発運動ではないか、という疑問。あるいは、福島やその近隣に限らず、東京エリアからも避難という苦渋の決断をした人たちが集会を開催することによって、自分だけでなく、他人を感染のリスクに晒すことは妥当だろうか。もし、基調講演を依頼された人が遠隔なら講演を行う、としたら、主催者は実施する義務があるのだろうか。こうした状況下で我が身をどこに置くべきか、倫理的な疑問がいくつも浮上した。

結局、9周年目に向けたイベントは、規模の大小を問わず延期、あるいは完全に中止となった。なかでもFriends of the Earth Japan(フレンズ・オブ・ザ・アース、 これよりFoE Japan)は、際だって大規模なイベントを企画していたが、それも取りやめとなった。FoE Japanは、核の問題に特化したグループではないが、2011年以降、教育の分野、あるいは放射線の監視など、地に足のついた活動で福島の問題でも群を抜いている存在だ。独自の丹念な調査に基づく声明を発表するだけでなく、FoE Japanは政治参加の方法に馴染みがない市民向けにパブリック・コメントの書き方のワークショップを開き、六ケ所村の再処理工場の問題や、太平洋への汚染水放出の問題などについて、自らの考えを表現できるようになる機会を提供している。2019年、オリンピックでますます災害の痕跡(それは避難者の数であったり、除染から生じた汚染土の処理であったり、健康問題であったり)の消去に拍車がかかっている現状に対抗するため、FoE Japanは、「ふくしまミエルカ」プロジェクトを立ち上げた。2020年3月のシンポジウムでは福島からの作業員、チェルノブイリで「清算人(リクビダートル)」と呼ばれた事故処理に送り込まれた作業員、避難者、医者、学者、ドイツの医者やエネルギー研究者などを迎え、東京と福島の2ヶ所での発表を計画していた。さらに、4月には「ミエルカ」の一端として、FoE Japanは若者をドイツのワークショップに送り出し、ドイツのみならず、フランスやベラルーシといった国の若者とつながる機会を計画していた。しかし、一連の企画も残念ながら実現しなかった。放射能と同じく目に見えない新型コロナウィルスは、間違いなく目に見える形でその力を地球の隅々まで発揮した。その力は、何がうやむやにされてきたかを暴くと同時に、情報などを秘匿する機会をも与えてしまった。

経済的支援もないままに「自粛」の日々が続いたことでもたらされた影響は、言うまでもなく社会的に最も弱い立場の人たちに大きくのしかかることとなった。これは、脱原発を支持する人たちの「火急」の意識を強固なものにした。というのも、コロナウィルスが社会全体にその力を可及的に発揮するのを目の当たりにしただけでなく、コロナにより、例えば原発の「処理水」という名の汚染水を太平洋に流すといった、自分たちが頑張って反対してきた案件が容易に通ることになりかねない事実に気づいたからだ。また、およそ30件近い福島に関する訴訟が国中で起きているなか、裁判の期日が延期、あるいは中止となり、原告、弁護士、そして支援者による裁判所での集会や記者会見を開く機会が奪われてしまった。こうした集会は原告の為のみならず、注意を払うべき我々一人一人にとっても重要であり、裁判官に対し世間がこの問題に関心を持っていることを知らしめる機会もある。なかでも、際だって活発で幅広い層の原告を含む(福島の強制避難者と福島と福島以外の「自主避難者」)原発賠償関西訴訟団はこうした条件下では対面で集えないことから、ビデオ・メッセージ作成という手段を取った。このビデオでは、自分たちの目標が「ふつうの暮らし、避難の権利、安全な未来」であることを視聴者に喚起し、原発事故避難者が新型コロナ下でどのような暮らしを強いられているのかを垣間見せた。ビデオは参加者がどこまで姿を見せるかについて、様々な立場があることを示してくれる。ある参加者は顔と本名を全て出し、ある者は顔は出しても名前は下の名前だけ、あるいは仮名で出演、そして声のみでの出演も見受けられた。こうした選択も避難者の状況について示唆的だ。

延期により、オリンピックの圧力が一時的に遠のいたものの、原発災害がもたらした様々な影響について、これら活動家集団はコロナウィルスと闘いながら語り続けている。

以下、2020年3月26日、ひだんれん武藤類子共同代表の挨拶と「二つの緊急事態宣言の中で 私達が生き延びるのは「真実を知り、助け合うこと」(とめよう!東海第二原発首都圏連絡会 ニュースNo. 4 (2020年6月)の英訳が続く。

Notes

The original wording, “Fukushima wa orimpikku dogo de nee,” which quoted a senior citizen from a township hard hit by the nuclear disaster, has been adopted by many activists. My translation used in this article, “Fukushima ain’t got the time for Olympic Games” is an attempt to suggest the flavor in English.

Although the extent to which air quality has improved is debatable. See, for instance, NPR (May 19, 2020).

20 Millisieverts for Children and Kosako Toshiso’s Resignation (APJ-Japan Focus, December 31, 2012). It has been standard for most countries to follow the recommendations of the International Commission for Radiological Protection (ICRP): 20 mSv/yr for occupational exposure (averaged over a 5-year period, not to exceed 50 mSv in any given year), 1 mSv/yr for the general public. See Japanese government site providing a Comparison between ICRP Recommendations and Domestic Laws and Regulations. These standards are subject to fierce contention worldwide, from both those who find them too protective and those who find them inadequate. The Japanese government has made 20 mSv/yr the de facto threshold for reopening restricted areas. See discussion in Jobin, The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster and Civil Actions as a Social Movement (APJ-Japan Focus, May 1, 2020).

On Ishihara and the Olympics, especially with respect to overlapping aspects of 1964 and 2020, see Tagsold (APJ Japan Focus, March 1, 2020).

In 2009 Hiroshima City and Nagasaki City submitted a single bid for summer 2020, appealing to the principle of promoting peace that, after all, constituted a cornerstone of “Olympism.” The mayors of the two cities linked the bid to the goal of nuclear abolition by 2020 (Asahi Shimbun, October 10, 2009), but the plan failed to make headway against the one-city rule. The Hiroshima-Nagasaki bid was not necessarily supported by hibakusha, as exemplified by the trenchant criticism, utterly applicable to Fukushima, of Yamada Hirotami (age 78), then Secretary-General of the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Survivors Council (Nagasaki Gembaku Hisaisha Kyogikai): “If the Games were to be held in Nagasaki, it would be an enormous technical and financial burden. […]They say that holding the Olympics in the cities where the atomic bombs were dropped means lots of people coming from all over the world, and that would raise awareness about nuclear abolition, but I think it would just detract. During the 1964 Olympics, even here in Nagasaki, everybody was swept up. How many gold medals did we get—that sort of thing was all that anyone could talk about. In that kind of frenzy, any interest in nuclear abolition goes out the window. [As with previous Olympics] there’s the risk of getting distracted by commercial priorities. […] There’s an atmosphere that makes it hard to voice opposition when they say that the Olympics are for the cause of spreading peace, but we need to discuss this rationally. […]The activism of Japanese hibakusha has gained the respect of NGOs around the world. We’re not about performance” (Nagasaki Shimbun, October 24, 2009). The Olympic-nuclear connection is worthy of examination in its own right, beginning with the striking use of Hiroshima in the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. There, the runner of the last leg of the torch relay, the one to light the cauldron, was Sakai Yoshinori, born on August 6, 1945 to be sure, but in Hiroshima Prefecture, not City. That fact was conveniently overlooked, and he was quickly dubbed “Atomic Boy.” Perhaps this was an initial source of ambivalence (Tokyo Shimbun, June 3, 2020), but he became a lifelong believer in spreading the message of peace through the Olympics (Withnews, September 10, 2014).

On the challenges of branding Tokyo 2020, see Kingston (APJ Japan Focus, February 15, 2020). Kingston has edited two special collections on the Olympics, here and here.

A position elaborated in a collection with the title, Shiawase ni naru tame no “Fukushima sabetsu” ron (2018) (Discourse on “anti-Fukushima discrimination”: For our happiness). “Real harm” (jitsugai) is sometimes used to contest the widespread use of “reputational harm.”

The addition of baseball and softball was finalized in August of 2016 though both sports have been dropped from the roster for Paris 2024. Azuma Stadium in Fukushima City was approved in January of 2017. The decision to start the torch relay in Fukushima came more than a year later, in August of 2018. Only one baseball game, in contrast to six softball matches, have been scheduled for Azuma Stadium. Olympic softball is a women’s sport, cautioning us to keep in mind research showing radiation exposure resulting in disproportionately greater harm to women and girls than to men and boys. See Gender and Radiation Impact Project.

On March 23, 3030—the day before postponement of the Games was announced—TEPCO held a press conference at which it disclosed that, in accordance with its own standards, it had returned J-Village to its owner foundation without first decontaminating it (Okada, Toyo Keizai, March 27, 2020). Subsequent disclosures, both through TEPCO’s press conferences and responses to Toyo Keizai magazine’s freedom-of-information filings, have revealed additional egregious transgressions, such as TEPCO’s storing radioactive waste exceeding 8000 Bq/kg on J-Village grounds and the prefecture’s demanding that TEPCO not disclose the location of such storage (Okada, Toyo Keizai, June 25, 2020). See Shaun Burnie’s “Radiation Disinformation and Human Rights Violations at the Heart of Fukushima and the Olympic Games” (APJ-Japan Focus, March 1, 2020).

See celebratory account in Hirai and Watabe, The Mainichi, March 14, 2020, and a more guarded one by McCurry, The Guardian, March 4, 2020.

The positioning of the lantern makes it seem as if this passage were written from the viewpoint of the flame (Yomiuri Shimbun, March 22, 2020). The extraordinary treatment accorded the flame, the rhapsodic attribution of hope made real, invokes the journeys—progresses—of Emperor Hirohito through the war-devasted country.

See Kingston, PM Abe’s Floundering Pandemic Leadership (APJ-Japan Focus, May 1, 2020) on the consequences of action delayed for the sake of the Olympics.

Reports of cost overruns have been predictably common, with the postponement now adding a hefty $2.7 billion according to the organizing committee.

See report on the first disclosures by Taakurataa by Our Planet-TV 2019. As for bringing “people back to their home towns,” the meagerness of such assistance as was provided beleaguered evacuees, both “mandatory” and “voluntary,” has also served as a powerful inducement to return. Late in 2019, Fukushima Prefecture doubled rents and threatened legal action (Our Planet-TV, August 29, 2019 and Taminokoe Shimbun, November 30, 2019). The Prefecture has taken four households to court even as their conditions have become further straightened because of the pandemic and associated loss of income (Hidanren, March 27, 2020).

A phrase often repeated in Fukushima. See Ogawa, “As If Nothing Had Occurred: Anti-Tokyo Olympics Protests and Concern Over Radiation Exposure” (APJ-Japan Focus, March 1, 2020).

In March of 2018, the Reconstruction Agency issued a 30-page pamphlet titled “Hoshasen no honto” [The truth about radiation] for widespread circulation through other government agencies, events within Fukushima and elsewhere, PTA gatherings, etc. True to the mission of the authoring agency, it argues in multiple ways that harmful health effects have not been shown to have resulted from the nuclear disaster. The text may be found here. In October of 2018, the Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology Ministry issued revised editions of supplementary readers, “Hoshasen fukudokuhon,” for elementary and middle/high school levels. These may be found with the 2014 versions here. The Citizens’ Nuclear Information Center (CNIC) critically reviews both sets of documents here (2019).

On the redispersal of radionuclides following weather events, see Burnie, Radioactivity on the move 2020: Recontamination and weather-related effects in Fukushima (Greenpeace International, March 9, 2020). Specifically with respect to the Olymics, see Burnie, Fukushima and the 2020 Olympics (Greenpeace International, February 5, 2020). Arnie Gundersen writes of the sampling trip he and Marco Kaltofen (Worcester Polytechnic Institute) took in 2017: “When the Olympic torch route and Olympic stadium samples were tested, we found samples of dirt in Fukushima’s Olympic Baseball Stadium that were highly radioactive, registering 6,000 Bq/kg of Cesium, which is 3,000 times more radioactive than dirt in the US. We also found that simple parking lot radiation levels were 50-times higher there than here in the US” [emphasis in original]. Atomic Balm Part 1: Prime Minister Abe Uses the Tokyo Olympics as Snake Oil Cure for the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Meltdowns (Fairewinds Energy Education, March 1, 2019).

Tanaka Shunichi, former head of the Nuclear Regulation Authority and now reconstruction adviser to Iitate Village in lecture at Fukushima City on September 18, 2019. Quotations taken from Fukushima Minpo’s lavish report, “Fukko arata na kyokumen e” (November 1, 2020). Much like a school teacher chastening and encouraging his pupils, Tanaka—himself only recently in a position of responsibility for government nuclear policy—directs the people of Fukushima to forget the promise by the central government to remove decontamination waste from the prefecture in thirty years’ time. This was, after all, their “own” waste. The article reports that 85% of the overflow audience of 2800 responded they were satisfied by the contents of the lecture. Only one critical respondent is quoted by the paper, to the effect that a promise by the government is a promise. The photo of the audience in rapt attention as they are being “given courage,” as one respondent puts it, to, in effect, embrace their victimization is haunting.

Personal emails. An immediate example of the “don’t test” approach is the prefectural survey of pediatric thyroid cancer. See Aihara, Follow Up on Thyroid Cancer! Patient Group Voices Opposition to Scaling Down the Fukushima Prefectural Health Survey (APJ-Japan Focus, January 15, 2017).

Government measures to contain the spread of the novel coronavirus have taken the form of “requests” (yosei) for “voluntary restraint,” or jishuku. See, for example, Japan Declared a Coronavirus Emergency. Is It Too Late? (New York Times, April 7, 2020.) The extent to which jishuku can lead to mutual policing and censorship will be familiar to those remembering the long final illness of Emperor Hirohito from late 1988-early 89.

For the original program, see here. For written and video messages from presenters, see here. The video messages of those who have stayed and those who have left are short, but informative and moving. Two are now available in multiple languages: former dairy farmer Hasegawa Kenichi here and evacuee Kanno Mizue here. See FoE’s informative statement in English released for the 9th anniversary here.

Contaminated water leaks have been a persistent issue for TEPCO, whether contaminated groundwater escaping from the basements of the reactor buildings and underground tunnels containing cables and pipes (Radioactive Water Leaks from Fukushima: What We Know (Scientific American, August 13, 2013) or from storage tanks (Fukushima daiichi gempatsu: Konodo osensui ga tanku kara moreru (NHK News Web, October 7, 2016). The difference now is that TEPCO is attempting to make contaminated water release the explicit solution to ever-accumulating storage tanks. “Treated water” (shorisui), the compliant media now call it, having cast aside the earlier designation of “contaminated water” (osensui). In 2018, TEPCO itself admitted that the ALPS filtration system had failed to remove, not just tritium, but other radionuclides at levels exceeding allowable limits in 80% of the contaminated water store in the forest of tanks. FoE Japan uses the term “ALPS-treated contaminated water” (ALPS shori osensui) and has taken a leadership role in public-comment workshops. See its summary of remaining radionuclides and the circumstances of TEPCO’s admission here.

See, for example, The Tokyo Olympics Are 14 Months Away. Is That Enough Time (New York Times, May 20, 2020). Just recently, Takahashi Haruyuki—he of the Seiko cameras as bargain bribes—became the first official to suggest that further postponement was possible, but that cancellation had absolutely to be avoided (Nikkan Sports, June 16, 2020).

See, for example, Yamaguchi and Muto, Muto Ruiko and the Movement of Fukushima Residents to Pursue Criminal Charges against Tepco Executives and Government (APJ-Japan Focus, July 1, 2012); Field, From Fukushima: To Despair Properly, To Find the Next Step (APJ-Japan Focus, September 1, 2016); Hirano and Muto, “We need to recognize this hopeless sight…. To recognize that this horrible crime is what our country is doing to us”: Interview with Muto Ruiko (APJ-Japan Focus, September 1, 2016).

For an authoritative account of the criminal trial and district court ruling, see Johnson, Fukurai, and Hirayama, Reflections on the TEPCO Trial: Prosecution and Acquittal after Japan’s Nuclear Meltdown (APJ-Japan Focus, January 15, 2020). On the significance of Fukushima-related trials, Jobin, The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster and Civil Actions as a Social Movement (APJ-Japan Focus, May 1, 2020). For statements by 50 complainants, Field and Mizenko, Fukushima Radiation: Will You Still Say No Crime Was Committed? (Kinyobi, 2015).

See also former Kyoto University nuclear engineer Koide Hiroaki’s views on the Olympics and the nuclear emergency declaration in The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster and the Tokyo Olympics (APJ-Japan Focus, March 1, 2019).

For a general account of the Tokai Nuclear Power Plant, see here. Tatsuya Murakami, who was mayor of Tokai Village at the time of the JCO criticality accident and took personal initiative to evacuate the residents, has been a leading voice in opposing nuclear restarts. TEPCO, on life-support with taxpayer money after the Fukushima disaster, has committed to supporting the aging Tokai No. 2 plant to the tune of $2 billion (The Asahi Shimbun, October 29, 2019).