Mutō Ruiko is a long-time antinuclear activist based in Fukushima. She represents 1,324 Fukushima residents who filed a criminal complaint in June 2012 pressing charges against TEPCO executives and government officials. In July 2015, an inquest committee decided that three former executives of TEPCO merited indictment, clearing the way for a criminal trial. This marked an unprecedented development in the history of criminal justice in Japan since indictment against the nuclear industry had never been granted in the country. On August 26, 2015, I visited Mutō in Miharumachi, Fukushima to hear about her activism, understanding of the Fukushima situations, and view of ecological issues on a global scale. Norma Field, a close friend of Mutō and a scholar who has been working on Fukushima issues since 2011, contributes an accompanying essay that puts this interview into a critical perspective. For details about the content of the criminal complaint and Mutō’s background, see Yamaguchi Tomomi and Mutō Ruiko, “Muto Ruiko and the Movement of Fukushima Residents to Pursue Criminal Charges against Tepco Executives and Government Officials” in the Asia-Pacific Journal (Link). (K.H.)

|

Mutō Ruiko |

How the Complainants for the Criminal Prosecution of the Fukushima Nuclear Disaster Came into Being

Hirano: Thank you very much for agreeing to an interview today. Ms. Mutō, you represent the organization, The Complainants for the Criminal Prosecution of the Fukushima Nuclear Disaster, which has sought criminal indictment of those deemed responsible for the disaster. A few days ago, an inquest committee decided that three former executives of TEPCO should be indictment, clearing the way for a criminal trial.2 First, could you explain how the Complainants group was formed?

Mutō: Concerning The Complainants for the Criminal Prosecution of the Fukushima Nuclear Disaster… I actually knew nothing about nuclear power plants until the Chernobyl accident. After that, I realized how dangerous nuclear power could be, and became deeply involved in the anti-nuclear movement. Before, there was a small group in Fukushima called “Fukushima Network for the Abolition of Nuclear Power,” which continued its activities on a smaller scale. After the accident in Fukushima, I had the opportunity to reunite with some members of this group.

We held two workshops to discuss things we could do as a group experienced in anti-nuclear activism. Many young people with children had evacuated outside the prefecture after the accident. It was at this moment when the link between those who evacuated and those who remained was getting weaker that I felt the urgent necessity to somehow find a way to reconnect.

We had planned a major event on March 26th and 27th, 2011, but the accident occurred two weeks before the date we had originally set. Everyone had evacuated and left. On March 26th, Saeko Uno-san from Kyoto – maybe she was in Kyushu at the time – suggested we hold a simultaneous press conference from each of the places we had evacuated.3 “Let’s tell the world about our difficult circumstances from wherever we are,” she said. Through this event we gradually came to realize how the evacuees were living their lives. Eventually, after several events and study camps, in January 2012, we came up with two goals: to pursue accountability, and to set up some form of official record like the hibakusha techō, a booklet that certifies one’s radiation exposure. You know about the Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Law. That took 12 years to become effective after the bomb was dropped, but we wanted to act more swiftly to establish such legal protection, and we wanted to follow the example of the Chernobyl laws.4 We weren’t actually able to accomplish much since we were only a small group with 20 members or so, but at least we identified two goals for the future.

In January 2012, we consulted with Mr. Kawai, the lawyer with whom we work now. At first, Kawai-san seemed to find our aims rather unrealistic. Soon, a writer named Hirose Takashi and Akashi Shōjiro, along with lawyer Yasuda Yukuo, filed a criminal complaint and wrote a book about it.5 We invited those three to our study group to discuss whether we could also attempt to file for criminal prosecution. Around 100 people gathered and there was great momentum to take this action. In March 2012, the Complainants for the Criminal Prosecution was officially inaugurated.

Hirano: The Fukushima nuclear power plant (NPP) had various problems even before the accident in 2011. In 1989, for example, there was a massive accident at Plant 2 Reactor Unit 3, where the circulation pump for sending coolant water into the reactor was broken, and the reactor was off line for almost two years. Mutō-san, you had already organized the Fukushima Network for the Abolition of Nuclear Power in 1988, and for over 20 years demanded that TEPCO investigate the cause of the problem in order to prevent future accidents. How did TEPCO respond to you back in those days?

Mutō: The damage at Reactor 3 occurred at the end of the year in 1989. The alarm went off and sounded continuously for about a week through the New Year holidays. At first I had no idea what was going on, but it turned out to be a serious problem. The recirculation pump was fractured – it is called the guillotine break – and, had it gone wrong, would have led to a terrible disaster. After this incident, many people in Tokyo who participated as consumers in the anti-nuclear movement came to support us, like Higashii Rei who is in Shizuoka right now, and Oga Ayaka who ended up moving to Fukushima – I think she had just graduated from high school back then. Many people from various backgrounds came and our movement gained a lot of momentum.

TEPCO had covered up the fact that the sirens had been going off for a week. This incident already reveals their tendency to hide the truth. When they were going to resume operation, we held a referendum about whether local residents were for or against restarting the reactor. We visited residents individually and handed out flyers discussing the dangers. We went on an all-female hunger strike, and there were others who set up a tent and started something like an Occupy action. We tried many different things, but we weren’t able to stop them.

Around that time, we began negotiation meetings with TEPCO. Each month, we would go to places like the service halls in Fukushima Plants 1 or 2; the publicity people from the plants would come over and answer our questions, and we would hand them documents listing our demands. We continued this monthly negotiation for 20 years until the accident occurred. Resuming this activity after two years of hiatus following the accident, I noticed that TEPCO’s corporate culture essentially remains the same (laughter). Even now, once a month, we hold negotiations with TEPCO for about three hours and end up almost feeling sick.

Hirano: What sort of attitude do they display during those three hours?

Mutō: Well, you might say they’re obsequious, or—they act as if they’re truly sorry, but when we start pressing for details, they fly into a rage.

Hirano: They get mad at you? (laughter) Wow.

Mutō: Yes, they get angry. Basically, they have no awareness that they’re the perpetrators. They think that they’re the victims.

Hirano: Why the victims?

Mutō: Of course they realize that TEPCO is the one that caused the accident. But from their perspective, they probably feel that it was the tsunami that brought about this unfortunate situation and they were frantically doing their best, so why should they be getting such complaints?

The predisposition of the organization might be something like “We’re not doing anything wrong, we’re the ones with the highest technology and proper understanding of the situation, which ordinary citizens can’t grasp.” Of course they won’t say this directly to our face, but this is what it feels like.

Hirano: They brush you off with condescension. The gap between citizens and experts is unavoidable because ordinary people are ignorant and uneducated.

Mutō: I always sense that. Sometimes we just can’t take it anymore and feel like bursting out, “This is too much!” “We are the victims! You brought this on us, don’t you understand!?” Maybe this is too grandiose, but I think we have an opportunity to rethink what “development” means. They believe that certain sacrifices are inevitable. Using nuclear power to generate electricity requires sacrifice on a fundamental level, right? But is it really okay for us to keep thinking that certain sacrifices are necessary for the sake of development and economic outcomes? We need to revisit this question. This is a human rights issue.

Developmentalism and Sacrifice, Education and Victimhood

Hirano: So from your perspective, at the core of the nuclear power plant issue, as you just mentioned, is the idea of developmentalism (hattenshugi/発展主義). The nuclear power plant is the ultimate outcome, in the most disfigured form, of an idea that prioritizes development, that a society will and should continue to maximize wealth at the expense of certain peoples or communities. Is this how you feel?

Mutō: Yes, that is the very symbol of a nuclear power plant. Especially, the idea of “necessary sacrifice” is embedded in a structure of discrimination against those who are sacrificed. The nuclear accident revealed the structural problem in which those subjected to discrimination have been exposed to a stupendous amount of danger for the benefit of big corporations or those who live in the city. However, this danger has been concealed with the power of money and the safety myth, and even after the accident, when people have become victims, they are hindered from recognizing themselves as such. Being a victim means that you must make a conscious effort to become aware of your victimhood. Otherwise, you become numb, or are made to become numb, to the fact that you have been subjected to something very unreasonable. I think that is one of the main issues.

I often feel like shouting out, is it really okay if we end up just crying ourselves to sleep? I know everybody’s concerned about life and livelihood, and that a lot of energy is taken up there, and that there’re important things we want to protect. But the way in which people are constantly being discriminated against, exploited, and faced with outrageous situations in this social structure—if we don’t gain self-awareness of these things, it’s going to be difficult to change them from our end. So I think it’s extremely important to be conscious of our victimhood. Then, as we gain consciousness of our victimhood, I think we start seeing our own participation in victimization, which also needs to be examined.

Hirano: I could not agree more. In your book From Fukushima to You you wrote, “We have been molded into citizens who do not speak out – citizens who have had to lock up their anger.” You also mentioned this point during the “Goodbye Nuclear Power: Gathering of 50,000.” As someone who has long been part of the field of education, do you think this difficulty in recognizing one’s victimhood is somehow related to Japan’s educational system?

Mutō: Previously, I had been teaching at a school for people with disabilities. My connection with them has had a big influence on me. It is obvious that they have been socially oppressed for their disabilities. Yet, those who are mentally challenged, for example, are in a very difficult position to point this out and try to change the situation with their own hands, though of course, there are many who have bravely fought for it.

Also, facing these disabled students as a teacher, you find yourself in a position of power in the school – inside the classroom, you are the authority figure (laughter). Of course, it was fun spending time with the children, and there was a lot I learned from them. There were many things I couldn’t handle on my own. But to be a teacher in a school is to be in an awfully powerful position, and you look down from on high. I’ve always felt uneasy being in that position. I’m not very smart so I can’t express this feeling with the right words, but I’ve always wondered, what is this structure? There are certain wonderful aspects of education, but when you think about how schools came into being, you have to think one of its purposes is to produce people conveniently suited for the needs of the nation, to mold citizens convenient for society.

Hirano: Especially compulsory education.

Fear and Deception, Despair and Accuracy

Hirano: In your speech at the Gathering of 50,000, you said, “After half a year has passed [since the accident], it has gradually become clear that the truth is concealed. The State does not protect its citizens. The accident has not ended. Fukushima residents will be turned into the subjects of nuclear experimentation. A stupendous amount of nuclear waste will be left. There exists a force bent on promoting nuclear power despite the sacrifice already made. We have been abandoned.”6 Unfortunately, it seems like these words accurately foretold what would soon become reality. It has been four years since the accident, but the situation has not changed.

Mutō: No it hasn’t. I feel a sense of shock over how reality has become exactly as I depicted. Why did I write this at the time? But it is true I already had this feeling then. Sometimes I wonder if I should have written this sort of thing. But you are right. What I said has become true. It might actually be worse.

Hirano: You started this speech with an apology, an apology to the young generation. Why did you want to start your speech like that?

Mutō: That was about leaving behind the waste. Radiation will not be gone during our lifetime. We can’t clean up this thing that would last for hundreds, even thousands and tens of thousands of years. We will die, leaving the waste with them. I couldn’t bear that fact.

Even without the nuclear accident, young people were already under awful pressure. They didn’t feel good about themselves, they couldn’t feel confident. Add to that, radiation exposure. Young people who were exposed—wouldn’t they become self-destructive, wouldn’t they be bullied and hurt. How could they have any self-confidence? These thoughts burst into my mind. So of course we have to apologize, I thought. The nuclear waste is bad enough, but the psychological burden we’ve imposed seems huge. I couldn’t help wondering if this wasn’t a generation that wouldn’t be able to find the power to push back.

But I shouldn’t generalize. There’re lots of young people coming forward. The other day, I ran into Okuda-kun, you know, one of the leaders of SEALDs (Student Emergency Action for Liberal Democracy) at a park in Kamakura. I had a chance to talk with him for a bit. Watching somebody like him, I can see that there’s an imagination and footwork and a sensibility we don’t have. If I think about that, I begin to feel that even though their approach is totally different from ours, they’re going to be able to overcome this situation. That’s the feeling I get from talking with young people. Not all of them, but some. That’s why I want to be hopeful, and I want to say to them, please, you’ve got to love yourself. That’s what I want to tell them.

Radioactive contamination and exposure is a frightening, serious issue. That is a fact, so I don’t want people to look away, but at the same time, I don’t want this to be a movement purely motivated by fear. I want us to choose a different route, to bring imagination to the movement.

Hirano: You have repeatedly made the point that you do not wish it to be a movement motivated by fear. Can you elaborate?

Mutō: Well, radiation is indeed terrifying, but I think emotions like fear and anger are something we don’t really want to see in ourselves. “Legitimate anger” is a necessary part of our emotion. Yet, you suffer greatly when beset by emotions like anger and fear, right? It is hard to watch others feeling angry. I am the type of person who can’t really deal with those who are livid or speak aggressively. I myself am not very hot-tempered. I am not good at giving in to my feelings and letting my anger explode, even if harsh words come to mind. There are good and bad sides to this, but I can’t endure the pain of experiencing such anger. That’s why I want so much to be calm.

In my speech, I described the people in Fukushima as “the ogres of the Northeast quietly burning their anger.” I put a lot of thought into the word choice of “quietly.” Of course, anger is very important, and you have to be angry, but I want that anger to be calm. Now, people tell me that we can’t be so “quiet” with our anger, and I think to myself, that’s not exactly what I mean (laughter). But everyone can interpret it differently, I think (laughter). So, yes, I want to stay calm and look intently at reality. Even despair. I want to take on despair, too, and despair properly. It’s by looking at it squarely that I want to go about finding the next step.

Hirano: You want to calmly accept despair as despair. Otherwise, you cannot find the next step or discover new hope. Is this what you mean?

Mutō: I think humans can’t go on living without hope. But we need to acknowledge this hopeless sight before us. This is what our nation is doing. Our anger and sadness will deepen and mature. That can give birth to the prospect of a future. Everybody’s different, I know, but for me, I am a person who wants to know (laughter). I just want to know the truth.

Hirano: I see. You want to have a clear idea of the situation, even if it is an absolutely hopeless one.

Mutō: Yes. Of course, I do feel angry and sad. But I really hate the feeling that there are things I don’t know (laughter). That is a strong desire in me.

But there is no way I can have a full understanding of the truth about everything, and frankly, I can’t hold too many things in my mind anymore. There is just too much information, so it’s a somewhat painful task. But there’s a lot of information that I don’t need to know, so maybe it’s a question of the ability to sift through information. I want to know before I act.

Hirano: As an activist in the position of leading a movement, has your experience led you to think that it’s extremely important to stay calm, and to speak and act based on a firm grasp of the facts?

Mutō: I do understand that in some cases it is also important to let your emotions show. But if you only pick up and transmit the incorrect, most sensational parts, there are lots of people who will gladly seize on them [for their sensational effects]. But if in fact, what you’re saying is a bit inaccurate, or includes many problematic issues, you’re likely to get tripped up. But at the same time, because so much is concealed, some details, what looks like fake information, might turn out to be true. It’s crucial to be able to make those distinctions. I guess I hate the feeling of being manipulated.

So if possible, I prefer to speak only after I’ve looked into an issue carefully. I have a lot of concerns regarding health threats, and certain things are showing up that make me wonder, but I feel it’s still early to talk about them yet.

Hirano: Are there examples from here in Miharu-machi (三春町)?

Mutō: Yes. For a long time I’ve maintained the position that while I do have concerns about health issues, I can’t speak to them. Starting around this year, however, many people around me in their 20s, 30s, 40s and 50s have died. Just this year, eight or nine people whom I know died. Half of those were sudden deaths, like heart attack. According to surveys, Fukushima is now ranked at the top in all of Japan for heart disease. It was fifth in the nation until 2011 so there was quite a lot of cardiac disease to begin with. But to be at the top in the whole country after 2011. I can’t help thinking there might be some connection.

Hirano: What do you think about the responsibility of those scholars receiving government patronage who came to Fukushima right after the accident and defended the safety myth? In your first Complaint, they (Yamashita Shunichi, Kamiya Kenji, Komura Noboru) were included, right?7

Mutō: Yes.

Hirano: So they came here and claimed that it was safe even after the accident. They spread the safety myth: “100 mSv is fine. Under 10 mSv/hour, it’s safe to play outside.” When some people raised concerns about health, they would respond with irresponsible and irrational arguments like “If you worry too much, you really will get exposed.” How do you think their presence affected the residents of Fukushima?

Mutō: Oh it was massive. It certainly played a huge role in providing a strong sense of security. It was March of 2011 when these people came. They had already done a seminar in Iwaki city at the end of March. After that, they went around the cities with high radiation levels like Iitate village, Fukushima city, and Date city. On May 3rd, I went to a talk by Yamashita Shunichi (then at Nagasaki University) in Nihonmatsu city (二本松市). There were already some people who weren’t feeling just right. So there was a suggestion passed around various mailing lists that we wear something yellow if we weren’t feeling well. So I went with a yellow bandana.

During that talk on May 3rd, Sasaki Michinori – he is from the local temple in Nihonmatsu, the husband of Sasaki Ruri, who appears in Hitomi Kamanaka’s documentary film “Little voices of Fukushima” – asked a question of Yamashita-san. “Would you bring your own grandchildren here and let them play in the sand box at a daycare center in Nihonmatsu?” Then he answered, “Of course I would. I’ll bring them.” I thought, wow. I hoped he wouldn’t actually bring his grandchildren there (laughter). After that, one after another, people wearing some yellow item asked him questions. In the end, he was sent off to applause from the whole room. An acquaintance who was a schoolteacher happened to be sitting next to me. She said, “That was a great talk.” But I still remember the last words he said. When many people criticized him, he lost it. He said “I am Japanese. I follow what my country has decided.” That was his final remark. Many people thought this comment was wonderful. In March, while I was still away, having evacuated, people would call and tell me about this professor who was giving lectures in Fukushima, appearing on radio and TV many times, and that the local paper wrote up a Q&A article using his words. “Apparently this scholar is a second-generation hibakusha (被爆者—those exposed to radiation) from Nagasaki, and a doctor who went to Chernobyl.” This is how he gained trust.

I think more people have come to realize the truth now, but I think everyone trusted him a lot.

Hirano: I see. Because they are all worried, they tend to be drawn to those who say the words they want to hear.

Mutō: Yes. So I personally find it very hard to forgive them, especially these three people. Extremely unforgivable, and that is why we included them in the complaint. However, as expected, it is extremely difficult to prove the correlation between radiation and health issues.

That’s why I thought that it was necessary to collect a lot of data in order to be able to pursue their crime effectively, but I was also afraid the statute of limitations might run out in the meanwhile. It’s hard to balance these factors. I am not sure what I should do.

|

The red colored part of Route 6 was opened to the public. It is only 1.5 km away from the power plant, and cut through the areas designated in beige as uninhabitable for now. (picture provided by Mutō Ruiko) |

Hirano: So if you had the data to prove the correlation between health and radiation, you would want to pursue the responsibility of these scholars once again.8

Mutō: Yes, yes I do, of course. I really want to. However, this has become an impossible task for just us. I hope more complainant groups will form, especially involving those in the medical profession, so these three can be indicted.

Hirano: So professionals are reluctant to participate in the movement?

Mutō: I wonder. Within Fukushima, it seems it would be very difficult to defy the Prefectural Medical University. The Fukushima Medical Association might be developing a sense of crisis about radiation exposure. But, I don’t really know how things are in the medical world.

Hirano: I feel that the most prominent example of official irresponsibility can be seen in the return home policy. What do you think?

|

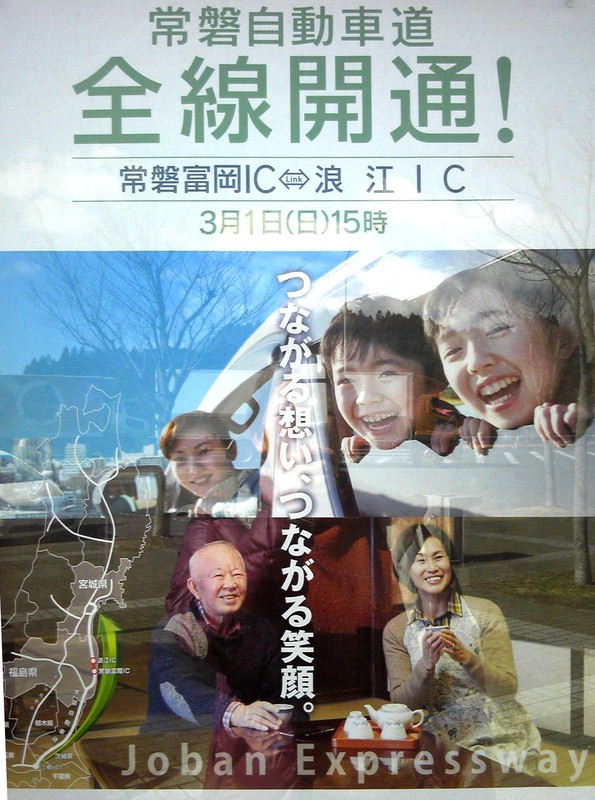

The poster that declares the road is complete and opened to traffic. It says “connecting thoughts, connecting smiles.” In some areas of Route 6 that are close to the Fukushima Daiichi, people are advised not to open the windows while driving. The poster promotes the completely opposite view. When I drove on Route 6 this summer (2016), most cars I encountered were trucks, vans, and cars used for decontamination and reconstruction works. (photo provided by Mutō Ruiko) |

Mutō: The return policy started at the end of 2011, and the elimination of the relocation zones was among the many things that occurred under this policy. For example, Route 6 opened last September. At its closest point, this national road is only 1.5 km away from the power plant. Anyone can pass by there, even children. Some data show that the radiation level measures 4-7 mSv even inside the car.

Hirano: Inside the car.

Mutō: Yes, inside. The levels get higher if you get out of the car.

Hirano: You shouldn’t get out of the car, shouldn’t even open a window.

Mutō: Right. There are barricades all along the expressway, and police are standing guard in some places. These policemen are all being exposed to radiation.

This March, the Jōban Expressway was declared complete and opened to traffic. They didn’t have this section completed before the accident. They hadn’t been making progress. It was only after the accident that they proceeded with the construction. There’s an electronic bulletin board that says “Today’s Radiation Level: 5.5 mSv.” It was about 4.9 the other day. I haven’t passed by there yet. I don’t even want to go on Route 6. Here’s a poster that a friend brought back from the service area. “Connecting thoughts, connecting smiles,” the tagline says, with children smiling with their faces outside the car window. It is horrific, like wartime promotion of using your hands to catch mere bombs.9

Hirano: Wow. Once it reaches this level of dishonesty and manipulation, it is nothing but propaganda.

Mutō: It is indeed propaganda. These things are actually happening in Fukushima and other affected regions.

|

Area where some police officers and construction workers remain active on Route 6. The radiation level is 5.5 mSv. (2015). When I drove through the Tomioka-machi area near the Fukushima Daiichi this summer (2016), a bulletin board indicated 4.8 mSy. (photo provided by Mutō Ruiko) |

Gender and Activism

Hirano: Let me switch to a slightly different topic. In your involvement with activism, you have always placed emphasis on the power of women, pursuing a shape of activism that makes use of feminine sensibilities. Could you elaborate on this point?

Mutō: Yes. This sentiment is rather intuitive. When we filed the complaint the first time, we originally named 33 people, only one of whom was a woman, someone from the Ministry of Education. I think that it’s mostly men who are responsible for shaping this nuclear society. For a long time, men were in the position of nation-building. In a way, those who were on the frontline of the postwar economic boom were all male. They were forced into such competitive positions.

Those deeply embedded in that kind of world have difficulties shifting their perspectives when social values must change. I think these men are “worn out,” so to speak.

It’s true that women took part in creating that society as well, but I think women may still have some energy left. In that sense, I think they might have a set of values different from those of the society we’ve had. It sounds simple when put into words. During my involvement with the earlier anti-nuclear movement in Fukushima, or the one at Rokkasho village, there were many moments where I found myself working with other women and feeling at ease.10

Hirano: Is it because you were able to empathize with each other and share many things in common?

Mutō: Yes. It was like, “Hey, what do you think of this, do you think we should do it?” “Oh that sounds good.” Teamwork felt so easy in such an atmosphere. Certainly, there was a lot of painstaking work to be done, like writing texts. We would do that, but generally, we didn’t have to discuss much. I really liked how we could proceed under empathic consensus.

Hirano: What kind of values and sentiments were you able to share the most? For example, was it something like “The nuclear issue is immediately relevant to our lives and livelihood,” or “What concerns our children must be our highest priority,” or “It is dangerous to live with only economic development in mind?”

Mutō: Well…I can only say how “comfy” (rakuchin/楽チン) it was. The basic line is that, first of all, what’s important are those things that immediately affect our everyday lives.

Hirano: Ah, the feelings and sensibility of the everyday. Not some grand theories about the state or unions, but the sensibility of a living being, rooted in the mundane.

Mutō: Yes, well those things might actually become more directly tied to things like life, the earth, and the universe. So instead of being caught up in petty discussions, we could rely on our instinctive senses about what we feel is important. I appreciated that kind of atmosphere.

Hirano: I see. On the contrary, when you work with, or negotiate with, other men, do you face moments where things don’t work well? Are there things you cannot seem to communicate well or feel uneasy about?

Mutō: Well, not all men are like that, and I try to work with them (laughter). But there are moments where it feels more difficult to communicate. Demonstrating power relations for example. I feel a little sad about that. If they cannot agree on something, they are not satisfied until they defeat the other side. In a situation where you could just say, no that’s it, they have to keep pressing the point. Also they always argue about who does what (laughter). To me, it feels like a waste of energy to argue about such power dynamics and different stances.

Hirano: Related to your earlier comment, perhaps men felt as if they had discovered the meaning of life when working hard as a “soldier” for corporations or government bureaucracies, especially after the post-war economic boom. Such an ethic continues to burden them, even when they are working for organizations like anti-establishment unions. As a result, it has become difficult to liberate their imaginations and social relationships. They’re unable to hold more flexible, multidimensional values or ideas that lead away from common sense.

Mutō: Right. In a way, I feel sorry for them. For us, our student years (1970s) coincided with the Women’s Liberation era. Feminism is a more recent term, but that kind of sentiment already existed. We breathed that air, although we didn’t quite know what exactly it was about. On the most basic level, a sense of equality and the idea that women are fun and strong and smart, have always been present inside me.

Hirano: Is that something you strongly felt when you were young, perhaps during your college years?

Mutō: Perhaps. During college, I shared an apartment with a girl with whom I got along. At that time, many girls came to visit us. Everyday, our place was filled with a sense of sisterhood. I had a boyfriend too, but I found it more interesting spending time with those girls. It was fun.

So everyone in general – and this remains the same today – women can do household chores, right? Some men are good at it too nowadays; my current partner can do household tasks much better than myself. It’s so easy to work with someone who has those skills. For example, even when organizing a simple get together, everyone ends up doing just the right task without having to meticulously decide each person’s role. “She did the cooking, so I’ll do the cleaning.” Things operate so naturally.

When we did an all-female camp at Rokkasho village, the men got upset about limiting the participants to women (laughter). When we told the old guys in the village that it was a women’s camp, he asked me when were we holding the “real” camp. No, this was the real one (laughter).

Hirano: (laughter). Things may have changed now, but it was such a division of labor between male and female that constructed the post-war society. Men were the breadwinners who fought outside and brought back money. Women did the mundane household tasks like laundry. Men have come a long way without having to deal with “everyday survival” so to speak, merely living as someone belonging to a company or organization, they have lost the experience and knowledge of living a life as a single individual. For this reason, their values and actions are also bound to the so-called “common sense” of the larger society and organization.

So when they burst into your activist group, things get more complicated (laughter).

Mutō: It just makes for extra work. We have to spell it all out—ok you do this, you do that (laughter). It’s like, I don’t have time for educating you (laughter). You know, these issues should already be behind us after all these years of anti-nuclear movements, from decades before the accident. Yet, there are still a lot of small things that strike us. For example, even when planning for this one meeting, they make comments like, “The MC should be a woman.” Huh? “Better have the statement read by a woman, too. Oh, but the opening remarks should come from a guy” (laughter). These are probably problems that they’re totally unaware of, that we’ve been aware of all along.

You might think that because teachers enjoy equal pay, sexism is not a very big issue, but this is not necessarily true. Take the division of labor, for example. Schoolteachers must take on administrative tasks, which are divided into different sections, such as research, administration, school lunch and health. The sections that women chair are always health and lunch. Always. All the schools were like that. Also, accounting. Even when there are two teachers in the same classroom, it is always the female one that does the accounting. I wondered why it was like that. I really thought, wow the education world isn’t any better.

Hirano: So this kind of discriminatory structure that has supported a systemic division of labor has reached the unconscious level. The most troublesome case is when a man who claims to be “progressive” ends up embodying that kind of view (laughter).

Mutō: Yes, yes, yes that is true (laughter).

Hirano: So including all those points, you can work with women more casually and communicate easily with a shared female sensibility.

Mutō: Yes. But that can also be said about the younger generation. They may be feeling something about our generation’s unconscious structure of discrimination. It is really important for people with different sensibilities to try something new in a different form. It doesn’t necessarily have to take the form of criticism. We can all learn new ways to think and act.

Tricks and Traps of Words

Hirano: Allow me to switch topics here. Terms like “Reconstruction”(fukkō/復興) “Reputational damage” (fūhyō higai/風評被害) “Hang in there” (gambare/頑張れ) and “Friendship” (kizuna/絆) – these words were everywhere, especially after the quake, and we still see them today all over the place. What do you think about the influence of these words and the meanings they have come to represent in society?

Mutō: Right. “Friendship” “Hang in there” “Reconstruction” “Reputational damage.” For example, there is one episode about reputational damage. I went to Minamata last month and learned that middle school students from Minamata came to Fukushima.11 Apparently, the students learned about radiation and found out that the food in Fukushima was safe. However, they discovered, that consumers were not buying the products at all because of the damaged reputation. “So, let’s send them to Minamata, and let’s have our school lunch at Minamata using made-in-Fukushima products,” the middle schooler proposed. Such a shocking thing could happen. I could not believe what I heard. “What?!” I said.

I met a mother who wanted to address this issue at the PTA. She told me that some adults in Minamata supported the idea, saying, “What a wonderful idea by a middle school student. Let’s all do it!” She asked me how she could argue against them. I said, yes this is a problem.

Of course, there are some Fukushima products that are safe, but there is no need to send them all the way to Minamata where they already have safe food. Nor would there be a guarantee that only safe things would be sent. “Reputational damage” is meant to refer to damage caused by false rumors stirred up about something without any basis whatsoever, but in the case of Fukushima, it’s not just some fabricated rumor. Some products actually show high levels of radiation contamination. I was so shocked about how this kind of thing could possibly happen.

I heard that this school lunch project is undergoing some difficulties right now due to the extra costs required for air shipment. I really hope the project will fall through. In other news, my friend at Minamata sent me a newspaper article about middle school students who baked a dessert using Fukushima products and won a patisserie contest. “In hopes for helping out the reconstruction of Fukushima,” they claimed.

Well, words like “Friendship” have cleverly taken advantage of people’s pure, or not-so-pure, feelings of sympathy. Their willingness to help has been exploited.

For me, the term “reconstruction” entails an environment where everyone can truly feel safe, their livelihood fully recovered. This is what reconstruction means in a true sense, not simply bouncing back to old habits like a shape-memory alloy. Reconstruction is a word that has been constantly redefined. The rhetoric of helping others was also used in the sense that, “It’s unfair to let Fukushima deal all by itself with contaminated rubble, so other places should share the burden.” With regard to the disparity between regions accepting contaminated rubble, the word “Friendship” was deliberately misused. I think it is disgusting. These words can move people’s hearts so easily, but they don’t accurately reflect the reality. These words carry a considerable burden of guilt. These things can be divisive. Many traps lie in Fukushima, so I try not to get caught in them.

Hirano: One of those traps which you mentioned is a misplaced morality and sense of righteousness: “As a true Japanese, we should do certain things in order to root for Fukushima.” You could call this the contemporary ideology of national morality. What other kinds of “traps” are there that provoke division among the people?

Mutō: Hmm, perhaps things like geographic division. They created areas called the Specific Areas Recommended for Evacuation. This produced disparities such as one side of the road being so designated while the other side wasn’t.

The issue of compensation is very big as well. Just yesterday, my friend who works at the agricultural coop visited me. She is this perfectly moral citizen. She says that people in the Restricted Areas are receiving tons of money, which they use to play pachinko and eat good food. Isn’t that a bit unfair since they are the ones who benefited from the nuclear power plant in the first place? They lost their houses too, but still. These financial matters gradually divide people from each other. For example, those of us living around this area were able to receive 80,000 yen (laughter). But people in Aizu Wakamatsu (会津若松) only received 40,000 yen. Dividing the areas incrementally based on the amount of compensation or differentiating places qualifying for compensation also becomes one of the traps that give rise to antagonism. But complaints about unfairness shouldn’t be made toward the individuals, they should be directed toward the government or TEPCO. If you have also suffered damage, you could take legal action. It’s easy to be mistaken about where to direct our accusations.

Hirano: So people feel envious towards those who receive more money. You can no longer converse with those whom you used to know as a friend or neighbor, just because they drew a line between you two.

Mutō: Yes, right right. That also happens. Another factor concerning radiation—this is partly a problem of those on the receiving end—is the safety myth, the safety propaganda that keeps flowing in. I think everyone more or less feels anxious. Those who have children especially worry about the future of their own children and damage to the health of the future generation. If they are told that it is safe, then of course they want to believe it, right? They don’t want to dwell upon this issue any longer because it is troublesome, tiring, and heartbreaking. For them, people who continue to worry become a nuisance – these irritating people who continue to say blasphemous things they would rather not hear.

Those in the primary sector, who are working hard to get their sales back to normal, feel that people who still worry about radiation are obstructing the path of reconstruction. This is another way the local population continues to be divided. If there were a legitimate form of compensation, like providing them with land to allow them to restart farming elsewhere, maybe they wouldn’t have to fall into that trap.

On the one hand, there are intentionally created divisions. On the other hand, distances deepen because of the weakness and insecurity fundamental to human nature, such as feelings of envy towards people who are doing better than you (laughter). These two are easily tied together. The government spreads the “safety myth” by exploiting this tendency. I believe that such strategically well-planned operations might have been inspired by how Chernobyl was handled.

Hirano: This is rule by division.

Mutō: Yes. I think they are good at this method.

I have a friend in Rwanda. I was teaching her Japanese when she was in Japan a bit before the civil war. She went back to Rwanda, but she evacuated to Japan again when the war broke out. When I asked her about the civil war, she told me that even though it is often understood as an ethnic war, that was not really the case. It was the status system created under Belgian rule.

Those who were originally of a single ethnicity were divided into three tribes, with those having a certain number of cows designated as one group, those with fewer another group, and those living in the forests yet a third. Only the highest group was hired under colonial rule, so when Belgium left, a dispute broke out. Hearing this story I realized how instituting divisions is tightly linked to governance. I thought, perhaps the same thing happens everywhere in the world.

Hirano: Those who benefit from the current administration are afraid of people turning against them in solidarity.

Mutō: Yes.

Hirano: Inevitably, money gets in the way.

Mutō: Yes, it is human nature to succumb to money (laughter). Alas, they get caught up in it.

Hirano: Do you feel that kind of pressure during your involvement with the anti-nuclear movement and effort to have criminal charges brought against TEPCO and government officials. As the trial unfolds, you may face realities which you don’t want to be reminded of. You may end up shedding light on truths which not only the government or TEPCO, but also the residents of Fukushima, don’t want to know. Would emotions erupt concerning why they need to face these difficult realities after all these years? Facts will come out that are disagreeable not only to the government and Tepco, but to Fukushima residents, too. Is it possible that emotions will be stirred up, about why people need to confront such painful truths at this point?

Mutō: Hmm, that might be true. For one, I want those who suffered damage to participate. Since the victims are limited, I am currently talking with the surviving families of the Futaba hospital. Fifty elderly patients died during and after evacuation. The doctors and nurses of the Hospital could not find evacuation sites equipped with appropriate facilities during the evacuation. The elderly patients died of dehydration, stress, and the lack of intravenous drip after over 14 hours of road trip. In many cases however, they tell me they would like to be left alone. “We’ve been compensated, there has been a settlement, and we don’t want to be involved any further.” For one thing, I’ve wanted the victim-participation model to be adopted. Since who counts as a victim has been delimited, we’re now in discussion with such parties as the bereaved families from Futaba Hospital. Please leave us alone, some of them say. The compensation issue is over, we’ve settled, and we don’t want to be involved any more.

There’s that, but also the fact that after the decision to indict, opening the path for a trial, the first attacks came from the mass media. They focused on the fact that of the nine cases where a Committee for the Inquest of Prosecution decided in favor of indictment, only two led to a guilty verdict. That’s the message they wanted to spread. Even articles written in the spirit of welcoming the indictment and the truths that might come out were apt to end up with such pessimistic observation. Other articles were skeptical from start to finish.

Hirano: One of the big goals of the trial is, as you mentioned, putting an end to the system of irresponsibility that is prevalent throughout this nation.

Mutō: That hope is definitely present. I don’t know if we can put an end to it completely, but it is important to call attention to this system of irresponsibility. I do believe that our action can be meaningful in leading us closer to the truth, and we sincerely think that the same tragedy should never be repeated again. In order to achieve that, the victims have our own responsibility. My political involvement with this issue is driven by a sense of obligation.

Since I don’t think that our activities can resolve every problem, we must incorporate different approaches and different movements – we need a variety of complaints and lawsuits. I would be much happier if we received messages of support, “We will take action as well, let’s fight together.”

Hirano: The first goal is to shed light on the irresponsibility of nuclear policy over time.

Mutō: Yes. Despite the numerous warnings or suggestions they had received concerning problems inherent in the Fukushima NPP, they failed to take necessary actions. They could have, but they didn’t. That caused the current situation. Even after the accident occurred, as we have seen, the irresponsibility continues, right? I doubt that anyone would take responsibility if anything happens at Sendai NPP.12

Hirano: Yes. For example, if a company causes environmental pollution, there will be a compulsory investigation in which the corporation’s legal responsibility will be investigated. Yet for some reason, it seems as if the nuclear industry functions mysteriously outside legal obligations.

Mutō: Right. That may be the power of “national policy,” but we can’t let them get away with it, can we? (laughter)

Hirano: As long as you claim to be a society under the rule of law, one who commits a crime must be tried. You are demanding what’s only commonsense, that they adhere to the law. But, both the nuclear power accident and the state of war expose the aporia wherein the law that is created by the state, can also be suspended in circumstances deemed exceptional by that state. “National policy” is a magic word that can normalize such an exceptional state. The perpetrators do not get tried and the victims are abandoned.

Mutō: Yes, that’s right. The law looks like it’s meant to apply to all people, but I’ve come to feel from my experience that it’s deliberately manipulated. But if you’re going to say that this is a country governed by the rule of law, and that this is a democratic society, then if, at the very least, people aren’t held responsible for what they’ve done, there’s no way to protect human rights. I think it’s important to hang on to the consciousness that states of exception shouldn’t be allowed.

I also think that it is not enough to merely pursue the legal responsibility of TEPCO or the government. I think each one of us was responsible. As discussed earlier, we have conveniently enjoyed our civilized society. We didn’t try to imagine what was behind the electric outlet. We are guilty of lack of imagination.

Hirano: You have insisted upon the impossibility of reconstruction in a true sense. If this is the case, then what kind of compensation do you believe to be appropriate for Fukushima residents? For example, do you think the government should have secured new land and homes for people who live in Fukushima (or other people who live in places with high radiation areas like Gunma, Tochigi, Ibaraki, Miyagi)? Should TEPCO have distributed resources in order to support people’s new lives?

Mutō: I think new land and housing should have been provided. Financial assistance for relocation should also have been provided.

The arbitrary return policy, legislated only to put an easy end to the accident while keeping the compensation price cheap, imposed a false sense of safety on people and unnecessarily exposed them to radiation. In other words, the government is telling them to give up and put up with the situation. The future is unpredictable due to their inconsistent attitude.

Hirano: The other day, when the committee for the inquest of prosecution called for indictment, you had a press conference under the banner of “citizens’ justice.”

|

Mutō holds the banner of “citizens’ justice.” |

Mutō: (laughter) In fact, I don’t really care for the word “justice.” (laughter) Mostly, it’s not used in a good sense, is it? It sounds like self-legitimation. Of course, it was meant to be a wonderful word. I wasn’t crazy about it, but everybody else was saying this was the way to go, so I just said, all right.

Hirano: But the way it came through on the screen, it felt good. They’re using the word “justice” in the way it should be used …. Good for them for talking about the issue in this way, I thought. The state just speaks using its own logic, right? The logic of the state and the logic of citizens, the way they look at things or the way things look to them—they’re totally different, I think. And you were talking about that clearly as a matter of justice. That’s what made me feel good, watching the press conference.

Mutō: Is that right? (laughter) I felt it was embarrassing. (laughter) But, if you think how citizens decided that indictment was appropriate where the prosecutors had not, you begin to see the difference, the gap between them. You referred to the difference between how the state sees things and how citizens see them, and I think that’s exactly right. What’s commonsensical for me isn’t so for the state, and the opposite might be true, too. I have to think that it’s not good to have this much discrepancy between the two.

Hirano: The government’s reasoning comes through clearly from the major media outlets, but citizens do not have the chance to retort, “No, we don’t see it that way,” or, “Your logic to me seems like a form of violence.” I believe there should be more space where these clashing views can be aired in public, on equal footing, so to speak.

Mutō: Yes. With regard to Fukushima, there have been dozens of negotiations with the government in many places. Yet, we really can’t hold an actual conversation with them, perhaps because government spokespeople are especially cautious on such occasions. We just end up talking past each other. In response to our questions, they say something that is completely irrelevant.

Do you know what they started doing recently? They send officials who are from Fukushima.

And then, before the negotiation begins, they say things like, “My family grave is also in Nihonmatsu,” “It has only been three months since I joined the Ministry of Environment, I’m from Fukushima.” They let some 23-year-old do this kind of job. They do disgusting things like that.

Hirano: Well, that is also a form of division. They can’t say no to their boss either since they started working there just recently.

Mutō: Yes. But I think that they must also feel a great deal of sadness facing other people from Fukushima. I think it is kind of disgusting.

Practicing Non-violence: Guerrilla Theater, Greenham Common, Rokkasho Village

Hirano: Could you talk a little about non-violence? Why do you place non-violence at the core of your activism?

Mutō: Let’s see. I first learned about the concept of “non-violent direct action” when a person called Agi Yukio, who wrote a book – what was the title – something about non-violence and direct action (note: Hiboryoku tore-ningu: Shakai wo jibun wo hiraku tameni, 1984) – held a workshop about non-violence training. This was about 30 years ago, right when we were doing the movement opposing Fukushima plants 2 and 3 in 1988. In Yokohama, there was a group called the “hi-boryokudan,” the non-violence gang. These people from the non-violence gang were the instructors for our non-violence training session.

I was wondering what it was all about when I went. First, we did an icebreaker to get to know each other. Then they taught us about “guerilla theater.” In guerilla theater, we produce a short skit, act it out in the middle of the street, and leave the scene right away.

There is a place called the “Bakugenjin village” which is like a hippie commune in Kawauchi village – my friends are there – and we put this guerilla theater into practice when we did a workshop retreat there. The village is close to Tomioka-machi, where they have Fukushiima 2-3. There was a service center for TEPCO, sort of like a building to promote nuclear power plants. It is shaped like a beautiful castle, and children would go and learn about the control rod inside a nuclear reactor or a whole-body counter – they even had things like that back then, a device that measures your internal radioactive level. We decided to storm into that facility singing anti-nuclear songs, perform a short skit, and run out. That was the plan.

Hirano: Oh I see, guerilla. In recent years they call it flash mob (laughter)

Mutō: So we actually went and did the skit. And then we came back. That was so fun (laughter). Afterwards, when I participated in the Rokkasho village movement, a lady named Kondo Kazuko showed a documentary film about a peace camp at a US military base called Greenham Common in the UK, where women camped for 19 years. Eventually the Greenham Common base closed down.13 It was a film called Carry Greenham Home. It was so interesting, how all women surrounded the base.

The women made their case through non-violent action. I was curious how they actually made it work. There’s a gate at the base that locks protesters out. When the women protest, the military shuts the gate. The activists thought, if they’re going to close the doors, why not try locking it? So they padlocked the gate from outside while the guards were not looking. In the morning, the guards were dumbfounded to find out the gate wouldn’t open, and try to cut the padlock open but to no avail. So eventually, they end up breaking down the gate. In an ironic turn of events, they themselves end up destroying the very gates that had prevented the protestors from coming in.

It was fascinating to watch. I found it intriguing to learn that non-violence does not simply indicate the absence of violent methods. Instead, it uses your ideas, body, and a sense of humor.

I’m not very good at public speaking, really, and I’m actually quite bad at writing as well. I don’t want to write or speak if I don’t need to. With “non-violent direct action,” you can become part of the action just by quietly being there. Your presence itself becomes a form of resistance. I thought that was great.

When we did the women’s camp at Rokkasho village, we decided to take non-violent direction action. We were going to lie on the ground and stop the trucks carrying radioactive materials. During the planning, I realized that non-violent action is not just one act, but includes a lot of elements like building relations with your friends and rethinking your lifestyle. At the camp, we made time to listen to each other’s personal histories and share our sufferings. Together we made a song for signaling to each other and we went to the beach to practice it. Everyday, we would cook food, eat, and clean up as a group while dividing the labor. This was really fun. It was the right kind of activity for me.

Also, because we chose direct action, there were limits to what we could do. We were only able to stop the trucks for 50 minutes. But then again, we did stop them for 50 minutes, and that gave us a sense of accomplishment. It was meaningful to realize that we were not completely powerless, and that we could take action in order to change the situation, however slightly.

Of course, this is not enough. Nothing can be solved just by doing this kind of thing. You have non-violent direct action, you have legal battles, you have protests and negotiations with the government, which might then lead to policy recommendations or elections resulting in representatives who’ll speak up. You need a variety of such activities. I think it’s good if we each participate in whatever we’re good at.

Hirano: I see. Listening to your story, I feel like you know how to enjoy life and cherish its moments. I mean, it must be hard standing at the frontlines and fighting like this. Very difficult. As you said earlier, you’ll be crushed if anger is your main driving source, and fear would not sustain you for very long. Even in that condition, you manage to enjoy life to the fullest and carefully build human relationship, always with a sense of humor. You are perhaps a kind of person who can do that naturally and flexibly.

Mutō: (laughter)

Hirano: Do you think that kind of attitude is important?

Mutō: Ah, yes, I do.

Hirano: For activism too.

Mutō: Yes, it’s too hard otherwise. It’s a lot of work (laughter). I think that maybe humans, no matter what the situation, can still appreciate a moment of beauty, fun, and delicious food. In whatever hardship you may be facing, you’ll probably still get hungry, too. I want to create something fun and beautiful like that.

Right after the nuclear accident, I was completely devastated. I like music, I can’t play any instrument but I really love it. Especially, I like the sound of the guitar. It has always been my morning routine to choose one CD and listen to it while drinking coffee. But after the accident, I wasn’t able to do that at all. I didn’t feel like listening to music. I just couldn’t.

Hirano: How long did that condition continue?

Mutō: About a year and a half to two years.

Hirano: That long.

Mutō: Yes, it was very hard. I couldn’t open up my heart, perhaps. But slowly I was able to listen again. There was a time when Lee Jeongmi, a zainichi Korean singer, came to Fukushima and sang a song for all the women in Fukushima. I think that might have been the turning point. Gradually, I felt like listening to music once more.

I think that things like art and sensibility are very important to political activism. This includes, for example, singing together with everyone, thinking about what clothes to wear, or what colorful protest signs to make for the demonstration.

Back when I was in Rokkasho village, there was a ship that showed up with high-level radioactive waste. There was a long fence by the port, and we tied colorful ribbons there. Also, right outside the nuclear fuel cycle at the reprocessing plant in Rokkasho village, there is a triple-layered wall. There is a fence on the outside, then a lot of cement sticks in the middle, then another fence inside. In that space in the middle, we threw in balls of dirt with flower seeds in them. When we went there the following year, flowers were blooming. Don’t you think that is kind of nice?

Hirano: That’s very nice.

Mutō: I don’t know if I can call it “art,” but I think these kinds of things are quite important.

Hirano: Yes. It sends out a message. It’s quite impressive that you could let flowers bloom at a place like that. You speak directly to people’s hearts and point out the issue from its very core.

Mutō: Yes. For the record, it wasn’t me who came up with this idea. Someone else had the idea and we all decided to do it. I thought it was quite wonderful.

But after the nuclear accident actually occurred, we were no longer able to take direct action at the actual site of Fukushima NPP. Sometimes we would do it at Koriyama or Fukushima, but we still wear masks. We all risk our own health to protest. We’re always wondering if we should be going that far.

In the fall of 2011 when 100 women surrounded the police station in Tokyo, we later found out that the radiation level was in fact quite high around there as well. But we all knitted a rope with colorful yarns and surrounded the area. I went around the premise, dancing. I want to continue engaging in those activities.

Hirano: You are saying that in Fukushima, it is difficult to carry out those fun activities where you speak to people’s emotions and express your thoughts?

Mutō: Yes. It’s hard to do it inside Fukushima. The other day, as we saw in the pictures earlier, we did a Hidanren (Gempatsu Jiko Higaisha Dantai Renrakukai, or the Liaison Council of Victims of the Nuclear Disaster) protest. Most of the participants were elderly people, demonstrating in sweltering weather, 38.6 degrees Celsius. I was so afraid they were going to collapse. The demonstration lasted about 40 minutes, but I thought to myself, wow, we are really putting our lives on the line (laughter).

|

Hidanren march. (photo provided by Mutō Ruiko) |

Why Kirara?

Hirano: (laughter). I also want to ask about Kirara, your home that was also a café until 3.11. Why and how did this begin?

|

Kirara in winter (photo provided by Mutō Ruiko) |

Mutō: I used to work at a school, but before I started up Kirara, I had many opportunities to reflect upon my own life in the course of the anti-nuke movement. As I questioned my lifestyle, I wanted to start cultivating mountainside land.

I went to a university called Wako University, in the age of the hippie movement. There was a countercultural trend to resist the society of convenience. I was only an observer at that time, but after I joined the anti-nuclear movement, I met people who were trying to conserve energy, using as little electricity as possible, and build their own house. It really made me want to live like that.

There was a mountain I inherited when my father passed away. It was just a wild mountain with nothing, but my partner and I decided to cultivate it. We started out with one mattock and slowly opened up a small plot of land. We built a lodge there. I wanted to live there without bringing many unnecessary things from outside, so we only had a lamp and a wood stove. We didn’t have electricity.

We lived like that for a few years, and it was just incredibly interesting to me. Soon, I didn’t want to continue teaching at school. Well, other things happened, and I eventually decided to quit my job. I had to think about what I was going to do after that, so I started looking for work I could do at home. Perhaps a café or a shop, I thought. So I used the land cultivated at the bottom of the mountain and built the structure for Kirara using my retirement money. That’s how it happened.

I wanted to use that space to hold study events about the energy problem, or set up an information corner about the nuclear power plant. I also wanted to plan live music events that would include discussions about modern technology and civilization. I made Kirara in order to create a space to transmit that kind of information.

Hirano: I see. Could you talk a little about your view of modern civilization?

Mutō: (laughter) I can’t really talk about modern civilization, but when I first learned about the existence of a TV, it was – how old was I – about when I was in elementary school, or sometime before that. My point is, when I was little, I didn’t have a TV or a refrigerator or a washing machine.

I’m 62 years old right now, but my lifestyle changed drastically within the past 60 years. It has really become convenient. But I wonder about the heat in summer, whether summer used to be this hot in the past. Of course we did feel hot since we didn’t have an air conditioner, but summer wasn’t as uncomfortably hot as right now.

In the meantime, many things were invented like a drier to dry your hair, or a pot that constantly provides hot water. Consumption of electricity thus greatly increased. People kept buying those devices, thinking they were convenient, but I started wondering if we were buying things that we really wanted. Such consumerism is related to things like how the “trending color” of a decade from now has already been decided, or the “10 principles of consumption” made by Dentsu (電通). I think the bullet train is convenient, but I wonder if we really need the “linear” (magnetic-levitation) cars. We used to be able to have a good time traveling without the bullet train, as long as we could take the time. But once you start using it, there is no going back. You use the extra time you saved on something else. People become busier and busier.

There is a picture book called “The Little House” (by Virginia Lee Burton).14 It was the first picture book we had in my house – someone had given it to my older sister as a gift. It is a story about a little house in the countryside that suffers the constant transformation of its surroundings. In the end, the little house is taken away to the countryside once again and lives happily ever after. But when you think about it, that story leaves behind the issues of the city. The little house went back, but the city just keeps on growing like that? After I grew up, I realized that that part hasn’t been solved in that story.

Hirano: I see, that’s true. I used to read that book all the time to my daughter when she was younger. The little house gets to move back to the countryside and regain its happiness, but I never thought about how it leaves behind the issue of the city. That’s a new perspective to reading that book. It becomes all the more real when you bring in the issue of the nuclear power plant into the picture, doesn’t it?

Mutō: Yes, yes.

Hirano: In order to support the material prosperity of the booming city, you need to build the nuclear power plant next to the little house that should have been happy in the countryside.

Mutō: Yes. I really identified with the story as my own. In the countryside I tried to build an ideal life, using natural energy like solar power, eating food from the mountains, farming on our own. The life I had was supposed to be as far away as possible from nuclear energy, while in reality, it was only 45km away. It destroyed everything about the way of life I had built. You can clearly see that story from the framework of the picture book.

Hirano: I see. You could get a little cynical and say that there is no longer a place where the little house can take refuge. No matter where you evacuate, there is no place on earth that is completely free of contamination. Modernity gave birth to that kind of civilization.

Mutō: Right. This really isn’t a problem of Fukushima. It is an issue for each living person on the face of the earth. I want people to know about the actuality of damage in Fukushima. I believe there is much to be learned from it, whether about the environment, the structure of discrimination prevailing in society, or what happens in people’s minds.

Since there are so many issues embedded in this problem, we as a species must learn many things from it. Especially with this nuclear accident, Chernobyl as well, we involved the lives of so many non-human species. I think that is a crime, or rather, a massive catastrophe.

Hirano: Yes. One of the reasons I visited Iitate village two years ago was to talk to farmers who could not sacrifice their horses or cows because they were part of the family.15 Animals can’t express themselves. All they can do is get sick from radiation and die. If they survive, the government will order them slaughtered. The dairy farmers were suffering. They also said that weird things were happening with wild animals they encountered.

Mutō: Yes. From their point of view, I’m sure it was a disaster out of nowhere. The wild boars must have thought, what in the world is this? (laughter)

Hirano: Right, just for human desire for more profit and convenience of life.

Mutō: I think they would wonder why their species had to suffer like this (laughter). They might not, but this is something we humans must think, us the perpetrators.

Hirano: Thank you very much for your time.

I would like to thank Ms. Mutō Ruiko for agreeing to do this interview. My sincere thanks extend to Norma Field who kindly reviewed and edited the interview and wrote the excellent introductory essay. Akiko Anson and Ryoko Nishijima made possible the publication of the interview by transcribing or translating it. I am grateful to both of them.

Related articles

• Oguma Eiji, A New Wave Against the Rock: New social movements in Japan since the Fukushima nuclear meltdown

• Yagasaki Katsuma, Internal Exposure Concealed: The True State of the Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant Accident

• Robert Stolz, Nuclear Disasters: A Much Greater Event Has Already Taken Place

• Katsuya Hirano and Hirotaka Kasai, “The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster is a Serious Crime”: Interview with Koide Hiroaki

• Arkadiusz Podniesiński, Fukushima: The View From Ground Zero

• David McNeill and Androniki Christodoulou, Inside Fukushima’s Potemkin Village: Naraha

• Noriko Manabe, Noriko Manabe, “Music in Japanese Antinuclear Demonstrations: The Evolution of a Contentious Performance Model,” The Asia-Pacific Journal 11, no. 42.3 (October 2013)

Notes

The title was taken from my email correspondence with Mutō of August 27th, 2015. She goes on to say, “it deepens our anger and sadness, and then allows them to mature; only after that will the perspective for a future be born, I believe.” She repeats this point in the interview.

Uno moved to Fukushima in 1999. She began to participate in the Fukushima network for the abolition of nuclear power plants in 2010. She became the chairperson of the association for the abolition of nuclear power plants, which was founded to demand the termination of nuclear reactors that were in operation for 40 years in Fukushima. Immediately after 3.11, she and her family evacuated from Fukushima, first moving to Kyushu and then settling in Kyoto. She continues to be active in various anti-nuclear and 3.11 related movements, working together with Mutō. She authored Mewo Korashimasho, Mienai Hōshanō ni (Let’s look closely, the invisible radiation). She and Nakasatomi Satomi, her spouse and a constitutional scholar, organizes a monthly study group at a café in Shintanabe, Kyoto, with locals and evacuees from Fukushima to share experiences and knowledge.

The Chernobyl NPP accident of 1986 led to the formation of the environmental rights movement and development of citizens’ rights to environmental information, which eventually resulted in laws of Ukraine, Belarus and Russia in the 1990s. Based on these laws, some legal scholars argue for the development of national and international law that will further ensure environmental human rights and processes of rehabilitation of ecological systems. In the case of Fukushima Daiichi, under the existing Abe government, debates leading to the installation of such laws protecting human and environmental rights have been absent.

In July 2011, Hirose Takashi, a writer, and Akagi Shōjirō filed a criminal complaint against Tepco executives who underestimated the seriousness of the nuclear disaster and mislead the public, and the scientists who denied any correlation between the nuclear disaster and illnesses such as thyroid cancer and heart attack by spreading the myth about the nonexistence of the danger of radioactive exposure. Hirose and Akagi also insisted that the disaster caused many deaths based on the fact that there were some farmers who took their lives out of despair and a number of elderly patients who lost their lives during the evacuation from hospitals. They expressed their concerns about the detrimental effects of radioactive exposure on Fukushima children who had been misled by Tepco and nuclear scientists working for the company and the government to remain for several months in areas heavily affected by radiation from Fukushima Daiichi after March 11.

As a radiation risk management adviser appointed by Fukushima prefecture after March 11, Yamashita lectured numerous times on radiation mainly in the prefecture. He claimed that radiation exposure of 100 mSv/yr was safe by arguing that when people were exposed to radiation does of 100mSV or more, the possibility of getting cancer increased only to one in ten-thousand people. He also reiterated that the radiation dose was equivalent to that of receiving 10 times the dose of one CT scan. Since CT scans are used for medical diagnosis on a regular basis, he argued, there is no danger involved in the Fukushima case. He made himself infamous and a focus of public criticism by stating that radiation affects only those who are concerned about its effects, but “not those who live with smiles”; adding that those who like to drink are rarely affected by radiation. He continues to serve as the advisor at Fukushima Medical University to this day.

Concerned scientists such as Koide Hiroaki have been advocating the necessity of carrying out thorough epidemiological studies. But the existing government under the Abe administration and TEPCO have shown no interest in conducting or sponsoring such research.

In 1941, Nippon Polydor released a song called “bakudan kurai wa tede ukeyo” (use your hands to catch mere bombs), state propaganda contributed by Eguchi Yoshi (music) and Fujita Masato (lyrics).

10 Rokkasho (六ヶ所村) is a village in Kamikita District of northeastern Aomori Prefecture in the Tōhoku region of northern Japan. As of September 2015, the village had an estimated population of 10,726. Since the 1970s villagers of Rokkasho and environmentalists opposed plans to operate Japan’s first large commercial plutonium plant in the village by focusing on the threat of a large-scale release of radioactivity. The facility in full operation is designed to separate as much as 8 tons of plutonium each year from spent reactor fuel from Japan’s domestic nuclear reactors. As of 2006 Japan owned approximately 45 tons of separated plutonium. Construction and testing of the facility were completed in 2013, and the site was intended to begin operating in October 2013; however this was delayed by new safety regulations. In December 2013 JNFL announced the plant would be ready for operation in October 2014. In 2015, the start of the reprocessing plant was postponed again, this time to as late as September 2018. Since 1993 US$ 20 billion has been invested in the project, nearly triple the original estimate. A 2011 estimate put the cost at US$27.5 billion. Consumers Union of Japan together with 596 organizations and groups participated in a parade on 27 January 2008 in central Tokyo opposing the Rokkasho Reprocessing Plant. Over 810,000 signatures were collected and handed in to the government on 28 January 2008. Representatives of the protesters, which include fishery associations, consumer cooperatives and surfer groups, handed the petition to the Cabinet Office and the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry.

Minamata disease was first discovered in Minamata city in Kumamoto prefecture, Japan, in 1956. It was caused by the release of methylmercury in the industrial wastewater from the Chisso Corporation‘s chemical factory, which continued from 1932 to 1968. This highly toxic chemical bioaccumulated in shellfish and fish in Minamata Bay and the Shiranui Sea, which, when eaten by the local populace, resulted in mercury poisoning. While cat, dog, pig, and human deaths continued for 36 years, the government and company did little to prevent the pollution. The animal effects were severe enough in cats that they came to be named as having “dancing cat fever”. As of March 2001, 2,265 victims had been officially recognized as having Minamata disease (1,784 of whom had died) and over 10,000 had received financial compensation from Chisso. By 2004, Chisso Corporation had paid $86 million in compensation, and in the same year was ordered to clean up its contamination. On March 29, 2010, a settlement was reached to compensate as-yet uncertified victims

The Sendai Nuclear Power Plant is located in the city of Satsumasendai in Kagoshima Prefecture. The Kyūshū Electric Power Company owns and operates it. The plant, like all other nuclear power plants in Japan, suspended operation since the nationwide shutdown in the wake of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in 2011. However, despite nation-wide protests, it was the first plant to be restarted on August 11, 2015.

Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp was a peace camp established to protest siting of nuclear weapons at RAF Greenham Common in Berkshire, England. The camp began in September 1981 after a Welsh group, Women for Life on Earth, arrived at Greenham to protest against the decision of the British government to allow cruise missiles to be based there. The first blockade of the base occurred in May 1982 with 250 women protesting, during which 34 arrests were made. The camp was active for 19 years and disbanded in 2000.