Abstract: Since Tokyo 2020 can’t really brag about tackling environmental issues, sustainability, cost cutting, or transparency, by default diversity and inclusiveness have become the branding agenda. This could be a positive legacy, but can the Olympics serve as a catalyst for Japan to reinvent itself? Probably not, due to the patriarchal elite’s ethnonationalism and aversion to diversity and inclusion.

These days one of the main rationales for hosting the Olympics is branding. While the 1964 Summer Olympics signaled Japan’s return to the comity of nations and promoted its high- tech prowess and recovery from war, the 2020 branding has proven more complicated and way more expensive. The government views hosting as a chance to showcase the nation’s many strengths, including its design prowess, superb infrastructure, social capital, and wants to parry the pessimism of those who have written off the economy and the nation’s prospects. There are also hopes that the games will further boost tourism, although there are many who think this is already too much of a good thing as arrivals in 2019 were nearly 32 million, almost double the figure in 2015.

In terms of PR, Tokyo 2020 had a very rough start, lurching from one debacle to the next, beginning with the decision to abandon the main stadium design by award winning architect Zaha Hadid (who since passed away). Partly this was due to massive cost overruns, with the price-tag soaring to US$2 bn, double initial estimates, but also on aesthetic grounds since it was a vulgar eyesore widely likened to a toilet seat.

Zaha Hadid’s Olympic Stadium Design

The new design for the national stadium by the Japanese architect Kuma Kengo has a less conspicuous profile and incorporates wood, imparting greater warmth, and was won general acclaim for doing more with less. (see below)

New Olympic Stadium (Photo: Jeff Kingston Jan. 2020)

(Photo: Jeff Kingston Jan. 2020)

Following the cancellation of Hadid’s design, it turned out that the selected Olympic logo was plagiarized and after insisting initially that it was not, the organizing committee hit the reset button and launched a new logo.

On left the design judged to closely copy the logo of a Belgian theater group.

The Olympic logo that replaced the plagiarized design. (Photo: Jeff Kingston)

This is not the first controversy involving how to visually pitch the games.

Japan Olympic Museum

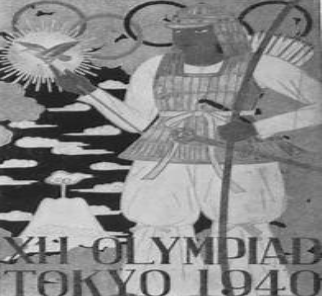

Adjacent to the new national stadium, the Japan Olympic Museum is shaped to resemble an Olympic torch. It has two floors of displays, videos and interactive features that attracts throngs on weekends and holidays. The large sculpture of five Olympic rings in front of the gleaming glass walled tower is a popular photo spot. Inside there are historical dioramas about the origins and evolution of the games, displays of logos from previous games and an interesting section on the 1940 Olympics. There is no reference to the controversy over the 1940 poster and there is almost no information about Tokyo’s decision to forfeit the games in 1938. After winning the bid in 1936, there was a public poster competition. The winning entry depicted the mythical Emperor Jimmu, said to be the first emperor, and creator of Japan, whose 2,600th anniversary was being celebrated in 1940.

Contest winner Poster featuring mythical Emperor Jimmu

While this winning entry seemed in line with the prevailing nationalist fervor, it was replaced by a more forbidding image with an athlete, right arm thrusting to the heavens, superimposed on the fearsome temple guardian Niō (仁王) whose left-hand rests on the man’s shoulder. Niō is well known to Japanese as the temple gatekeeper who wards off evil spirits. Perhaps representing Jimmu was seen to diminish his imagined grandeur.

Temple guardian Niō (仁王) has a menacing look. (Photo: Jeff Kingston Jan. 2020)

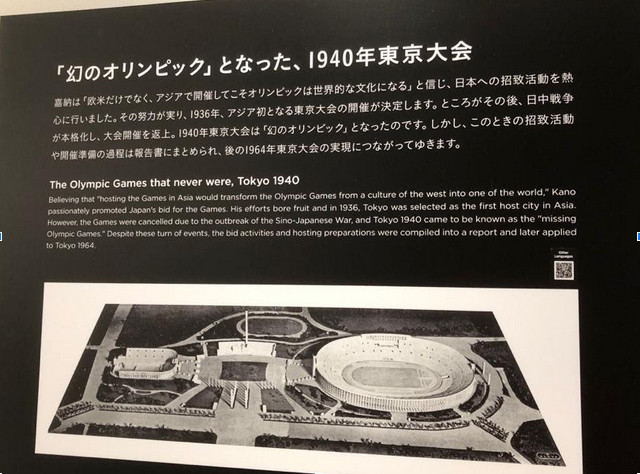

The display refers to the 1940 games as the “missing Olympic games”. The museum indicates that the games were cancelled due to the Sino-Japanese War (1937-45), without explaining the circumstances. Initially the Tokyo metropolitan government launched the bid and only after much lobbying won central government backing. (Collins 2008) Hosting the Olympics was presented as an opportunity to soften Japan’s image and address the ‘misunderstandings’ in the international community that followed Japan’s invasion of Manchuria in 1931 and withdrawal from the League of Nations in 1933. On July 7, 1937, however, when Japan made the fateful choice to escalate hostilities in China, Kono Ichiro, grandfather of current Defense Minister Kono Taro, was the first politician to call for cancellation of the games. He also opposed having the Emperor attend the Olympics or broadcasting a speech on the radio during the games on the grounds that it would be unconstitutional and unsuitable given his divine status. Amid growing international condemnation of Japanese aggression, and threats of a boycott, In March 1938 the War Minister asserted that hosting the Olympics would interfere with wrapping up the ‘China Incident’, and in June 1938 the government’s austerity budget made cancellation a foregone conclusion. The government was not prepared to provide the necessary funds or allocate sufficient steel for construction of facilities; the war effort was already stretching Japan’s economy. The Olympic spirit of internationalism was also out of step with the prevailing jingoism and on July 15, 1938 the games were forfeited and shifted to Helsinki, which was also forced to relinquish the games due to the outbreak of World War II.

Japan Olympic Museum display on 1940 Olympics (Photo: Jeff Kingston Jan. 2020)

Costs, Corruption, Sustainability, Recovery?

In 2013 when Tokyo won the right to host the 2020 Tokyo Olympics the cost estimate was just US$7.3 bn, but by 2019 the total costs ballooned to an estimated US$28 bn although the Tokyo organizers insist the figure is only US$12.6 bn. (Wade and Yamaguchi, 2019) The Tokyo government estimates optimistically that Japan stands to gain some US$283 bn in spillover benefits between 2013-2030 from hosting the games, but that legacy may prove elusive. (Nikkei 2017)

There was a major political battle over some no-bid contracts on white elephant Olympic projects that pitted Tokyo Governor Koike Yuriko (2016-) against a predecessor, Ishihara Shintaro (1999-2012), and former prime minister Mori Yoshiro (2000-2001) who were heavily involved in the promotion and planning of the games. It was entertaining political theater but, in the end, saved very little money. More importantly, the mudslinging proved awkward for the political establishment, since it reinforced public perceptions that the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) was putting in the fix to reward cronies and bilking the taxpayer. The squabble over who pays for what between Tokyo, surrounding prefectures and the national government also drew attention to the fact that many of the newly built facilities will struggle to generate sufficient post-Olympics revenue to pay for ongoing maintenance due to bleak prospects for attracting events and functions.

With massive cost overruns, Tokyo 2020 is not exactly a posterchild for affordability or sustainability, apparently ignoring the lessons of previous Olympics. And then there was the corruption issue that erupted in 2019. It was alleged that the Japan Olympic Committee (JOC) secured the bid by making illicit payments to a dodgy firm in Singapore with ties to an individual banned from any involvement in international sports due to corrupt practices.(McCurry 2019) After French authorities announced that JOC president Takeda Tsunekazu was under formal investigation on suspicion of ‘active corruption’, he resigned. Similar allegations were made about the Nagano Winter Olympics in 1998 and there is widespread skepticism about the transparency of the bidding process and the rent seeking behavior of some of those involved, but at that time the shredder solved all the problems of potentially incriminating documentation.

Tokyo claims this will be the greenest Olympics ever, but highlighting environmental issues has also backfired amid allegations of greenwashing. The so-called ‘recovery Olympics’ showcasing Japan’s post-Fukushima rebound confront grimmer realities about the delayed decommissioning of the stricken reactors and clean-up that will cost more than US$600 billion over the next four decades (Kyodo 2017). Furthermore, the 2020 decision to dump large volumes of Fukushima’s tainted water into the ocean highlights just how absurd PM Abe Shinzo’s ‘under control’ reassurances to the IOC were in 2013. Japan’s green credentials are also suffering from plans to build as many as 22 new coal-burning plants over the next five years, ramping up the dirtiest source of electricity. (Tabuchi 2020) Rapidly expanding the nation’s carbon footprint conveys a troubling complacency about global warming and public safety at a time when the Olympics subjects Japan to heightened scrutiny.

Tokyo, by the way, is sweltering in summer, but IOC delegates in 2013 were misinformed that balmy conditions prevail in the nation’s capital when the games are scheduled (July 24-August 9). As residents know, this timing coincides with some of the city’s muggiest and unpleasantly hot weather. For that reason, in 2019 organizers moved the marathon and long-distance walking events to Sapporo on the northern island of Hokkaido out of concern for athletes’ health. But there are other risks as well, including untreated raw sewage in Tokyo Bay that poses a significant health risk to competitors in certain swimming and boating events.

Reiwa: Era of Diversity?

Since Tokyo 2020 can’t really brag about the environmental impact, sustainability, cost cutting, or transparency, by default diversity and inclusiveness have become the branding agenda. This could be a positive legacy, but can the Olympics serve as a catalyst for Japan to reinvent itself during the Reiwa era? Some certainly hope so including the new Emperor Naruhito whose reign began in 2019. His role in the 1947 constitution is defined as, “the symbol of the State and of the unity of the people.”

Emperor Naruhito, while still crown prince in February 2019, celebrated his birthday by sharing his thoughts on his role as Japan navigates various challenges in the 21st century. Reflecting on his father’s reign during the Heisei Era (1989-2019), Naruhito characterized it as an, “age that witnessed greater diversity in the lifestyles and value systems held by the people.” He added, “It will be important to accept that diversity with a spirit of tolerance while seeking to further develop it through the mutual encouragement of each other.” He also spoke of a “new wind” that blows in each era and that he would also continue to seek out the proper role for the imperial family in line with the changing times. (Asahi 2019) Subsequently, he has reaffirmed his pro-diversity views, notably during his enthronement ceremony on October 22, 2019 on a day of driving rain. Just as he concluded his remarks, the skies cleared and overhead a rainbow emerged, suggesting perhaps that the gods are lending their support for LGBTQ rights, here a largely unrealized agenda of diversity and inclusion.

A Mainichi editorial commented,” In Japan, the Emperor’s status as a symbol of the unity of the people in the Reiwa era will come into focus. The age defined by the phrase ‘100 million, all-middle class,’ referring to the large proportion of middle-class workers in Japanese society, is long gone, and the previous sense of unity of the people can no longer be seen. The government is accepting more foreign laborers into the country, and domestically, globalism is progressing. Emperor Naruhito looked back on the Heisei era as one marked by diversity in people’s lives and sense of values and said a spirit of diversity and tolerance was important. The new image of him as a symbol may be based on these kinds of perceptions of a new era.“ (Mainichi 2019) There are some signs of progress on this aspirational agenda.

One Team: World Cup Rugby

In 2019 Japan hosted the Rugby World Cup, featuring an incredible performance by the Brave Blossoms, as the national team is known, that sparked an even more unlikely national passion for a game that has at best enjoyed modest popularity. The 6-week, multi-city extravaganza spread across the archipelago, was seen as a dry run for hosting the 2020 Olympics, testing out the logistics of handling an influx of tens of thousands of fans from around the world. Nobody predicted Japan would crush Ireland and hang on to beat Scotland, nations with long rugby traditions, and advance to the knockout stage. But in doing so the team ignited a frenzy of feelgood solidarity and demonstrated that the nation is ready for the Olympics. And, at least in sports, happy to embrace diversity.

It’s worth noting that almost half of the team was foreign born players (15 out of 31) from seven countries; the rules of eligibility don’t require citizenship, only thirty-six months of residence prior to joining the national team and not having been on any other national team. Jamie Joseph, the coach, is a New Zealander while Michael Leach, the captain, was born in New Zealand with a Fijian mother and father of Scottish ancestry. He graduated from Japanese high school and university and is fluent in Japanese. His stoic play, shrugging off injuries and painful hits, earned widespread praise as he epitomized the grit and tenacity often associated with samurai. He took it upon himself to educate the other foreign-born players about Japanese culture, history and etiquette, even insisting they learn how to sing Kimigayo, the national anthem.

Public support for the team verged on the ecstatic and the talents of the foreign players drew high praise. Advocates of Japan embracing greater diversity to remain globally competitive found a perfect example of why it makes sense. Exemplifying the 2020 Olympic motto of unity in diversity, the ethnically diverse Brave Blossoms came to be known as “One Team”, the top buzzword for 2019. Near my home one major shopping arcade always celebrates Halloween by hanging a very large jack ’o lantern made from papier mache at the entrance. This year I walked past and did a double take because the pumpkin sported the image of Michael Leach, an homage to a naturalized Japanese who had become an unlikely national hero.

Multiracial Japan?

The Rugby World Cup 2019 became a national celebration of diversity in a nation known for its insularity and homogeneity. Nothing like sports success to quiet the bigots, but can a handful of sports stars transform Japanese attitudes about ‘Japaneseness’? Certainly, the 2015 crowning of Ariana Miyamoto, the first mixed race Miss Universe Japan challenges notions of what it takes to be Japanese. Her mother is ethnic Japanese, her father is an African-American and she was raised here and is a Japanese citizen fluent in Japanese. Then in 2016 half Indian Priyanka Yoshikawa was crowned Miss World Japan, again subverting the ‘pure Japanese’ longing that persists among some Japanese. These biracial beauties don’t conform to traditional Japanese aesthetic standards but do demonstrate the gathering power of globalization and skepticism about notions of racial purity. And, contest organizers understand what it takes to win, endorsing the power of hafu as biracial children are called here. Perhaps the most famous hafu is Naomi Osaka, the young tennis superstar with two major titles and a high world ranking. She is hugely popular among the Japanese public for her on court prowess and her demure public persona. Her mother is Japanese, and her father is Haitian, but she pleased many in choosing a Japanese passport so she could represent Japan in the Olympics (and cash in on being a megastar in a nation starved for sports glory). But her prominence comes with controversy. In one ad for a popular instant ramen product, her image was “whitified” with her skin airbrushed to a lighter tone that also gave her Caucasian facial features and wavy brown hair, drawing strong criticism in the media. Bayle McNeil, a Japan-based African American commentator, suspects that this ‘whitewashing’ was motivated by the desire to enhance her commercial appeal and undermined efforts to showcase Japanese diversity and inclusiveness. (McNeil 2019)

Diversity Olympics?

The Tokyo games organizers declare that “unity in diversity” is a core concept for the 2020 Olympics and proclaim that, “Accepting and respecting differences in race, color, gender, sexual orientation, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth, level of ability or other status allows peace to be maintained and society to continue to develop and flourish.” In this spirit, in 2018 the Tokyo Metropolitan Assembly passed an ordinance prohibiting discrimination against sexual minorities and hate speech against non-Japanese. There are also high hopes among some Japanese that Japan will seize this opportunity to embrace diversity. As academic Yamawaki Keizo argues,” There may be a deep-seated image of Japan as a homogeneous and exclusive nation, but in 2020 the world will witness whether Japan is moving toward building a diverse and inclusive nation.” (Yamawaki 2020) Let’s hope he is right, but this may exaggerate the transformative potential of the Olympics. (Miller 2019, Weisbord 2015) In the media limelight, Japan’s multiracial Olympians may transform global perceptions of Japan, but after the confetti is swept away many challenges remain. While surveys indicate that Japanese are less xenophobic than negative stereotypes suggest, this doesn’t necessarily mean widespread acceptance.

A 2018 Pew Research Center survey found only 13 percent of Japanese respondents said there were too many immigrants in the country, while 58 percent said the current number was about right and 23 percent said there should be more. (Pew 2018) This compares favorably to 28 percent of South Koreans respondents, 37 percent of British, and 41 percent of French saying there are too many immigrants in their countries. It’s worth noting that this relatively positive attitude might be influenced by the low numbers of non-Japanese residents. As of 2019 there were 2.83 million foreigners living in Japan of which 1.7 million are working. Even so, non-Japanese residents account for just under 2% of the nation’s total population of 126 million.

A Nikkei survey found that almost 70 percent of respondents,” think it is ‘good’ to see an increase in the number of foreign people, both at work and in the community”. (Nikkei 2020) To some extent, however, it appears that Japanese are more resigned than enthusiastic about recent increases in the number of non-Japanese residents due to the need to mitigate labor shortages. According to the Nikkei survey,” While 31 per cent said Japan “should actively accept” foreign workers, 50 percent said ‘I don’t like it, but it can’t be helped.’ The future may be more promising, however, as, “The younger generation seems more open to foreign workers, with 48 percent responding that Japan ‘should actively accept’ them.”

Japan’s aging and declining population, and the labor crunch, is generating pressures to accept more migrant workers, but the government has made it abundantly clear it doesn’t support immigration. Instead, it has adopted visa rules designed to facilitate entry for foreign workers for a limited duration, ignoring abundant evidence that many will remain and settle despite government intentions. The conservative elite is hoping that advances in AI will alleviate labor shortages and enable Japan to fend off an influx of foreign immigrants. It is in this context that there are reasons to doubt that the Olympics will serve as a catalyst for diversity. Problematically, politicians are in denial about ‘stealth’ immigration and growing ethnic diversity while the national government’s minimalist approach to integration programs leaves cash-strapped local authorities to improvise inadequate arrangements that reinforce exclusion.

Gender equality is also in the spotlight as Japan’s global ranking continues to slide on PM Abe’s watch, dropping to a record low of 121 in the 2019 World Economic Forum index despite his vigorous grandstanding on ‘womenomics’. The gender pay gap is third highest in the 36-member Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), as women remain underrepresented in management and overrepresented in the non-regular workforce of low paid, dead-end jobs. Revelations that test scores of female applicants to medical schools were routinely downgraded to boost the acceptance of male applicants probably contributed to Japan’s low ranking. It’s hard to justify a policy designed to maintain patriarchal dominance of the medical profession.

Team Tokyo 2020 Celebrates New Year

It is further indicative that the Tokyo 2020 Olympic office greeted 2020 by posting a picture on Twitter of their virtually all male team in celebratory mood. There is a long way to go, but perhaps the Olympic spotlight will generate pressures to promote diversity beyond core concepts, uplifting rhetoric and symbolic gestures.

References:

Asahi, 2019. “Naruhito facing up to ‘gravity’ of becoming emperor in May” Asahi Shimbun, Feb. 23.

Collins, Sandra, 2008. The 1940 Tokyo Games: The Missing Olympics: Japan, the Asian Olympics and the Olympic Movement. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Kyodo, 2017. “Real cost of Fukushima disaster will reach ¥70 trillion, or triple government’s estimate: think tank” Japan Times, April 1.

Mainichi, 2019. “Emperor Naruhito proclaims enthronement as respected symbol of Japan”, Mainichi, Oct. 23.

McCurry, Justin, 2019. ”Japanese Olympic chief to quit amid corruption allegations scandal”, The Guardian, March 19.

McNeil, Bayle, 2019. ”Someone lost their noodle making this new Nissin ad featuring Naomi Osaka”, Japan Times, Jan. 19.

Miller, Joshua, 2019. “Multiracial athletes spark debate in Japan ahead of 2020 Olympics”, Japan Times, August 8.

Nikkei, 2020. ”Nearly 70% of Japanese say more foreigners are ‘good’: survey”, Nikkei Asian Review, Jan. 10.

Nikkei, 2017. “Japan expects $283bn boost from 2020 Tokyo Olympics”, Nikkei Asian Review, March 7.

Pew, 2018. “Perceptions of immigrants, immigration and emigration”, Pew Research Center, Nov. 12.

Tabuchi, Hiroko, 2020. ”Japan Races to Build New Coal-Burning Power Plants, Despite the Climate Risks” New York Times, Feb. 3.

Yamawaki, Keizo, 2020. “Japan’s move toward a diverse and inclusive nation?” Japan Times, Jan. 12.

Wade, Stephen and Mari Yamaguchi, 2019. “Tokyo Olympics say costs $12.6B; Audit report says much more” Associated Press. Dec. 20.

Weisbord, Robert G., 2015. Racism and the Olympics. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.