Introduction

On November 8, 2019 in Seoul, Wada Haruki delivered this urgent call to peace. It is in many respects a summation of his life’s thinking, and APJ presents it as such.

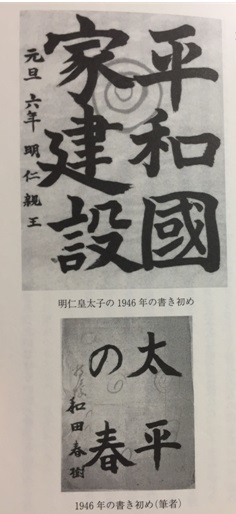

As Northeast Asia confronts the stark choice between constructive peace and its cataclysmic opposite, nuclear war, Wada forcefully demands peace, well aware that his plan —like others in his career—is a “sheer product of imagination.” That said, his imagined ideas, springing from a lifelong commitment to a world without war, are more important than ever. Born in Tokyo in 1938, one of Professor Wada’s recent books includes reproduction of the eight year old elementary-school hand-writing practice of the Chinese character for “peace,” which he juxtaposes below now-retired Emperor Akihito’s similar calligraphy homework (older than Wada by five years). For their shared immediate post-1945 era, “peace” was the order of the day; some students like Wada and arguably the former emperor learned; others did not.

|

Wada continues to push his work against this divided background in Japanese society—or, in Northeast Asian regional society—and in this talk he brings a new and remarkably bold way of understanding the 1951 Treaty of Peace With Japan, known more commonly as the San Francisco Peace Treaty. He stresses that the treaty did not establish peace but instead created the foundation for ongoing war between the United States and what would become North Korea as well as the People’s Republic of China and North Vietnam. In short, the “perimeter line” that Secretary of State Dean Acheson explained in his April 1950 speech would become hard reality by the terms of the treaty, and Wada, for his part, rejects this outcome. Ever since, he has spent his life defining “peace” in contradistinction from the Pax Americana-state sanctioned understanding, and in this recent talk he boldly—albeit imaginatively—offers ideas on how to accomplish it.

Abstract

This brief talk examines the San Francisco System—the geo-political order inaugurated in September 1951 in the combined terms of the San Francisco Treaty and the US-Japan Security Pact. The San Francisco System did not bring an end to war as many imagine; rather, it set the stage for war elsewhere—namely Korea. In short, the San Francisco System has provided the framework for the United States to continue fighting the Korean War indefinitely and has defined Japan’s place in this nexus. The system was strengthened during the Vietnam War, and only began to show signs of revision in 1972 with US-China reconciliation. The end of the Cold War brought US-Soviet reconciliation and the demise of the Soviet State Socialist system. Notwithstanding, an isolated Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea) remained in confrontation within the framework of the San Francisco System and has developed its own nuclear weapons. By the end of 2017, North Korea and the United States were on the brink of war. A dramatic change then took place: the Singapore Summit between President Donald Trump and Chairman Kim Jong-un opened a peace process, which ultimately could dismantle the San Francisco System. In the long run, I believe that a Northeast Asia community model will replace the San Francisco System.

1. Defining the San Francisco System

The San Francisco Peace Treaty was concluded on September 8, 1951. Forty-nine countries signed it, including Japan. Of these nations, the key signatories were six western nations—the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, the Netherlands, and France—and five Southeast Asian nations—Indonesia, the Philippines, South Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos. The Soviet Union rejected the treaty. The People’s Republic of China, the Republic of China, South Korea, and North Korea were not invited to the conference. As a result, any consideration of this treaty with defeated Japan as a peace treaty must recognize that it was partial and imperfect.

|

Japanese Prime Minister Yoshida Shigeru signs the San Francisco Treaty as John Foster Dulles (center) and Dean Acheson (right) look on. |

The San Francisco Treaty together with the US-Japan Security Treaty signed later that same day served to establish the US camp for continuing the Korean War and defining Japan’s position in it. We can call this the San Francisco System. In sum, the San Francisco System is an international state system that did not terminate a war but instead continued one: the Korean War. The enemy camp of the San Francisco System consisted of North Korea and the People’s Republic of China, and, implicitly, the former Soviet Union. The vanguard of the US camp consisted of the US forces in Korea, South Korean troops, and Chinese Nationalist soldiers based in Taiwan. American headquarters and the main strategic and logistic bases were in Japan and Okinawa (the latter still fully under American occupation until 1972 and the bases continuing to expand to the present). Nominally, Japanese self-defense forces were not counted among the war potential of the US camp because of constitutional proscriptions against waging war beyond Japanese territory, yet the San Francisco System embraced the entirety of the Japanese archipelago as an American base—very much including Okinawa—to guard its territorial integrity and security. Within this system, Japan played a key role as the main rear support of US forces. As such, the San Francisco System enabled the US camp to expand its war further against Chinese and North Koreans in 1952 and 1953. Following the conclusion of the armistice on July 27, 1953, the San Francisco System played a vital role in perpetuating hostilities between South and North Korean forces along the demilitarized zone (DMZ) dividing Korea.

2. Supplementary Measures to Strengthen the San Francisco System

In the wake of the meetings that led to the San Francisco Treaty, supplementary measures were taken to strengthen the system. First, on April 28, 1952 immediately as the treaty went into force, Japan concluded the Sino-Japanese Peace Treaty with the Chinese Nationalist government. President Harry Truman’s special representative, John Foster Dulles, forced Japanese Prime Minister Yoshida Shigeru to commence negotiations for a peace settlement with Chiang Kai-shek, and the first conference took place in Taipei on February 20, 1952. During negotiations, Taiwanese representatives demanded that Japan recognize its obligation to pay reparations to China and asserted that should such recognition be written into the treaty with the Republic of China (Taiwan) they would waive the actual benefits of reparations save for such services such as “salvaging and other work” already designated in the San Francisco Treaty. The Japanese side firmly rejected this demand and instead took advantage of Taiwan’s complicated political position within the San Francisco System to force it to drop all claims on behalf of China. There can be no doubt, however, that the 1952 Sino-Japanese Peace Treaty strengthened the position of the Republic of China within the San Francisco System and its related international order.

On October 16, 1956, Japan re-established diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union. When Prime Minister Hatoyama Ichiro began negotiations in June 1955, he made clear his determination to move beyond the San Francisco System view of regional and world affairs. The San Francisco Treaty obliged Japan to renounce all rights to the Kuril Islands and to Sakhalin. Hatoyama, however, pressed his negotiator, Matsumoto Shunichi, to secure the return of the Habomai Islands and Shikotan—a group of very small islands close to the eastern tip of Hokkaido that Yoshida had forcefully argued during San Francisco Treaty negotiations were not part of the Kuril Island chain.

Hatoyama believed that achieving “normalization of relations” with the Soviet Union would alter Japan’s position in the San Francisco System, yet when Secretary Nikita Khrushchev urgently ordered his representative, Yakov Malik, to accede to Hatoyama’s request for the two small islands, Hatoyama’s own Foreign Minister Shigemitsu Mamoru and other Yoshida-faction officials in the foreign ministry who wanted to prevent Japan-Soviet rapprochement worked together to demand the return of four islands or nothing—introducing the idea of the “Northern Territories” by including Etorofu (Iturup) and Kunashiri (Kunashir). Negotiations then taking place in London broke down immediately.

Ultimately, Hatoyama achieved a compromise and in October 1956 signed the Joint Declaration in Moscow. Normalization of diplomatic relations followed without resolving the territorial issue (where matters stand today). In the Joint Declaration, Khrushchev made clear his respect for Japan’s position and promised the return of the Habomai Islands and Shikotan once a peace treaty was achieved between Tokyo and Moscow. Yet, the Japanese government has continued to demand for all four islands, insisting that Etorofu (Iturup) and Kunashiri (Kunashir) are not part of the Kuril Islands. This false argument and unreasonable demand has blocked settlement between Tokyo and Moscow ever since—all in accordance with of the San Francisco System.

Talks began between Japan and the Republic of Korea (South Korea) under American auspices on October 20, 1951. South Korea’s representative immediately demanded an apology from Japan for the era of colonial rule. Yet, from the start the Japanese government strongly resisted this request and maintained a policy of no apology and insisted on the legitimacy of its colonial rule. After nearly fifteen years of negotiations, on June 22, 1965, the South Korean government reconciled itself to compromise and signed the Treaty on Basic Relations with the Republic of Korea. Article II reads as follows: “It is confirmed that all treaties or agreements concluded between the Empire of Japan and the Empire of Korea on or before August 22, 1910 are already null and void.” From the start, Seoul interpreted this article to mean that the 1910 annexation treaty was “null and void” at its inception, while Tokyo interpreted it to mean that the annexation treaty was valid until the Republic of Korea came into existence (a point of contention still in South Korean politics over whether 1919 or 1948 marks its origin; English is the ultimate language of the treaty). Such a serious division over interpretation of the most important article in the treaty should have been immediately remedied.

Together with this treaty Tokyo and Seoul concluded an agreement to settle issues over property, claims, and economic cooperation. Japan promised to give South Korea $300 million unconditionally and lent an additional $200 million in low and no interest loans. Article II of this agreement further confirms that issues arising from claims by both countries are “finally and completely resolved.” At the time, the South Korean government agreed to shelve its territorial dispute with Japan, leaving its possession of Dokdo (Takeshima) Island an ongoing point of contention between the two countries. The Japan-South Korea Treaty provided economic cooperation to the South Korean government and encouraged state-led economic development.

3. The Expansion of the San Francisco System

In 1960, the main theater of military hostilities between the US camp and the communist camp moved from the Korean peninsula to Indochina. The National Front for Liberation of South Vietnam was formed, and armed resistance began against the US forces who succeeded French colonial troops. The Vietnam War that broke out in this year was in a sense the continuation of the Korean War.

The San Francisco System dovetailed with this new war: the 1965 Japan-South Korea Treaty provided economic assistance to South Korea; supported by Japan, South Korea sent 50,000 ground troops annually, eventually more than 300,000 troops, to support the Americans in their war in Vietnam. North Vietnam was supported by the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China. North Korea wanted to aid North Vietnam by creating a second front in South Korea and in 1967 began building a “Partisan State,” sending an armed guerilla unit to Seoul on January 21, 1968 to attack the presidential palace. South Korean troops annihilated the Northern unit. Later on, North Korea sent pilots to North Vietnam to assist in air warfare. On the San Francisco System side, Okinawa again was the main base for US forces, and Japan remained a permanent logistical base as well as a major site for American military “rest and recuperation.”

4. Revision of the San Francisco System Begins in 1972

In 1971-72, while Vietnamese continued to fight against the US and its allies, PRC Chinese and American leaders concluded that the Korean War had ended in a draw. President Richard Nixon’s February 1972 visit to Beijing decisively changed US-PRC relations.

Japan raced to catch up with the United States and dared to establish its own diplomatic relations with Beijing, signing a Joint Statement of September 29, 1972: “Japan feels responsible for the enormous damage it has inflicted on the people of China through war in the past, and expresses deep remorse for this.” Twenty-seven years after the end of the war this one sentence was the first apology that Japan made to a victim nation in Asia. Apparently, the PRC was able to force Japan to acknowledge this fact. Yet at the same time Beijing was obliged to waive all reparations claims. It should have pushed Japan to annul the Sino-Japan Peace Treaty that had forcefully deprived Taipei’s China of the right to claim war reparations. Also, at the same time, Beijing decided to shelve the territorial matter of the disputed East Sea islands (the Senkaku/Diaoyu issue).

In 1978, Tokyo and Beijing signed the Japan-China Treaty of Peace and Friendship, and Tokyo began to provide Beijing with economic aid. The following year, Prime Minister Ohira Masayoshi visited China and promised a $150 million-dollar loan. Earlier, in 1972 Okinawan sovereignty reverted to Japan, yet the heavy burden of the massive presence of American bases there remained unchanged for Okinawan people.

Thus, in several ways, the San Francisco System began to shift, yet only slightly and only superficially.

5. The End of the Cold War and the San Francisco System

US-Soviet reconciliation at the end of the 1980s initiated a great world historical change. Revolutions and political transformations throughout the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe followed. The government of Mikhail Gorbachev sought radically to change not only the Russian political system but also its foreign policy, deciding first to have truly peaceful diplomatic relations with the US. Gorbachev also sought to establish diplomatic relations with South Korea. It seemed that the Cold War would end in Northeast Asia, too. Yet, this was not to be the case: hostilities between North Korea and the San Francisco System remained not only unchanged but were to intensify in the worst way.

Having lost its primary protector—the former Soviet Union—North Korea faced a state crisis in terms of its economic viability. At this historical juncture, North Korean leaders adopted two policies to mitigate the crisis: first, Pyongyang sought to develop its own nuclear weapons in lieu of the lost Soviet nuclear umbrella; and, second, North Korea attempted to normalize relations with Japan. In line with the San Francisco System, the United States vehemently denounced the first option and sought to negate the second option before it began.

In 1991-1992, the Japanese government tried to negotiate with North Korea, but Washington intervened and derailed this first round of talks. Eight years later, in 2000 a second attempt ended in vain. Only in the wake of a year of secret negotiations would Japanese Prime Minister Koizumi Junichiro and North Korean Chairman Kim Jong-il meet in Pyongyang and sign the Pyongyang Declaration on September 17, 2002. At that moment, the two agreed to move towards normalization between Japan and North Korea. Success of this moment, however, could not overcome the vehement opposition within Japanese circles and the new US-led intervention. Again, the process of Japan-North Korea normalization was suspended.

With “option two” of diplomacy proving unfeasible, North Korea clung to “option one” and carried out its first nuclear test on October 9, 2006. As a result, a new harsh reality of the conflict began between North Korea and the US. Fast forward a decade to 2016-2017 and the country’s new leader, Kim Jong-un, developed not only North Korea’s nuclear program but also its long range ballistic missile technology and capability while the US made every effort to block North Korea’s endeavors.

The San Francisco System had previously experienced serious transformations, yet Prime Minister Abe Shinzo and President Donald Trump strove to stop those processes and instead to reinforce the system in deep structural ways. They heightened economic sanctions and military intimidation toward North Korea (especially in 2017).

6. A New War Crisis; Efforts to Get Out of It

In 2017, the US-North Korea conflict reached crisis proportions. North Korea moved forward at full speed in its nuclear and ballistic missile projects. On March 6, 2017, North Korea fired four medium-range missiles over 300km towards Japan’s Akita coast, and the North Korean Central News Agency declared these tests ensured the potentiality of an attack on American bases in Japan. In his September 2017 speech at the United Nations General Assembly, President Donald Trump publicly threatened North Korean leader Kim Jong-un and vowed that he—meaning the United States military—would totally destroy North Korea should Kim not succumb to America’s demand for North Korea’s “complete, verifiable, irreversible denuclearization.” As always, Japanese Prime Minister Abe proclaimed agreement with President Trump on policy toward North Korea. Then, following President Trump’s visit to South Korea, three US nuclear aircraft carriers arrived in the region to put US capability on full display.

Nevertheless, on November 29, 2017, North Korea test-fired a new inter-continental ballistic missile (ICBM), “Hwasong 15,” which was estimated to be capable of flying over 14,000km. North Korea authorities declared that they had carried out “a historical accomplishment of state nuclear forces and a strong rocket state.” With this, the US-North Korean conflict entered a decisive stage: before us lay the possibility of a new US-North Korea war.

Throughout December 2017, concerned people endeavored to avoid such a crisis. Earlier, in the middle of November, the UN General Assembly adopted the “Olympic Truce” to try to persuade the North Korean government of its good intentions. The resolution appealed for understanding that, “Pyeongchang 2018 marks the first of the three consecutive Olympics and Paralympics Games to be held in Asia, to be followed by Tokyo 2020 and Beijing 2022, offering possibilities of new partnership in sport and beyond for the Republic of Korea, Japan and China.” The South Korean government conveyed this message to the North Korean leader Kim Jong-un through various channels.

Kim Jong-un examined the horrendous prospect of nuclear war and was persuaded to return to his father’s position: that of nuclear diplomacy. We can remember that Kim Jong-il once said to Prime Minister Koizumi: “We came to have nuclear weapons for the sake of the right of existence. If our existence is secured, nuclear weapons will no longer be necessary… We wish to sing a duet with the Americans through the Six Party Talks. We wish to sing songs with the Americans until our voices become hoarse.”

On January 1, 2018, Kim Jong-un made his new thinking public during his New Year’s address, expressing North Korean willingness to join the Pyeongchang Winter Olympic Games. Later, he expressed his wish to have a summit meeting with American President Donald Trump. For his part, President Trump, who also looked into the face of nuclear war, immediately accepted Kim Jong-un’s proposal for a US-DPRK summit—as relayed by South Korean President Moon Jae-in’s special envoy on March 8, 2018.

As a consequence, on June 12, 2018 President Donald Trump and Chairman Kim Jong-un held a summit in Singapore during which they conducted a comprehensive and sincere exchange of opinions on issues related to the establishment of new US-North Korean relations and the creation of a lasting and robust peace regime on the Korean peninsula. President Trump committed to provide security guarantees to North Korea, and Chairman Kim Jong-un reaffirmed his unwavering commitment to the complete denuclearization of the Korean peninsula. The result was that two tasks were put on the table: the first was to end the Korean War; and the second to denuclearize the Korean Peninsula. To me, this means that the San Francisco System should be dismantled now. Looked at differently, the Singapore Summit stopped the fear of further war between the US and North Korea and opened a new peace process in Northeast Asia.

7. The US-DPRK Peace Process: Source of Hope

Finally, it is time to move beyond the San Francisco System. To begin, all nations and all people in Northeast Asia should take responsibility for supporting US-DPRK negotiations. President Trump and Chairman Kim should work to formulate a program of peace and denuclearization of the Korean peninsula. I believe they should continue to strive to agree.

And yet, a year and a half have passed. To move forward, the two countries should agree as a baseline on the fifth clause of the fourth round of the September 2005 Six-Party Talks: “The Six Parties agreed to take coordinated steps to implement the… consensus in a phased manner in line with the principle of ‘commitment for commitment, action for action.’”

To me, it seems that in 2019, the US representative and the North Korean representative finally began again to negotiate in accord with this Six Party Talk rule. They have tried to bargain over the Yongbyon nuclear facilities as well as the US ban on North Korean coal exports and textile merchandise trade. Neither side has yet agreed to the other’s proposal, yet moving forward it would be wise for each side to read carefully what the other wants.

But this negotiation will be truly difficult. I believe that North Korea’s nuclear weapons might be dismantled only when the US nuclear umbrella over South Korea and Japan is ended. Although US forces in South Korea and Japan are themselves not nuclear armed, they fall under the broader aegis of American nuclear protection. In other words, I believe that the complete denuclearization of the Korean peninsula requires closing the US nuclear umbrellas over South Korea and Japan. Therefore, it is inevitable to discuss the issue of US forces stationed in South Korea and Japan.

Generally speaking, the task of complete denuclearization of the Korean peninsula cannot be separated from the task of denuclearization of the Sea of Japan, the Japanese archipelago, and Okinawa. This brings us to the first task of the US-North Korea peace process, which is achieving the complete end of the Korean War to bring about a true peace. Without this, people who have lived under the San Francisco System will never authorize withdrawal of US forces from their respective countries.

The South Korean government has made great efforts to promote reconciliation between North and South Korea. The two Joint Declarations adopted at Panmunjom and Pyongyang last year were a wonderful success. Today, however, North Korea is uneasy with the slow pace of change in South Korean policy towards the North, and the positive atmosphere has deteriorated. In South Korea, there is little feeling that war is a possibility on the peninsula, yet there is also little feeling of true mutual trust. Koreans in the South and the North do not share a common historical understanding of the Korean War, and without achieving some understanding, the memory of war will never cease to worry people.

The situation now is rather primitive. The South Korean government is unable to change its policy towards Gaesong and Gumgangsan because it cannot alone persuade the US government to change course (the former is the site of South and North Korean economic development plans; the latter a joint tourist venture). In this instance, Japan’s Abe administration is a real obstacle to South Korea’s Moon Jae-in.

On March 8, 2018, when President Trump consented on the spot to Kim Jong-un’s proposal for a summit, his action shocked Prime Minister Abe who immediately rushed to call President Trump and explain that no sanctions should be relaxed until North Korea completely abandons its nuclear weapons program and resolves the issue of Japanese abductions to North Korea as the latter remains the most vital issue for Japanese.

Prime Minister Abe’s policy concerning Japan’s abduction issue with North Korea have long prevented Japan from normalizing relations with North Korea. Abe’s proclaimed his Three Principles in 2006 when he became prime minister for the first time. Number one is that the abduction problem is the most important problem for Japan. Number two there can be no normalization of relations between Japan and North Korea until the abduction issue is resolved. And, finally, number three is that the Japanese government will continue to presume that the unaccounted-for abductees are still alive and will strongly demand their return. The final principle means that Japan views North Korea as a liar (North Korea informed Japan that it abducted 13 Japanese citizens; of whom 8 were dead; 5 alive). This third principle made it impossible for Japanese diplomats to conduct normal negotiations with North Korea.

After the June 2018 Singapore Summit, Prime Minister Abe said he would meet with Chairman Kim with no preconditions to solve the abduction problem, yet he has done nothing to promote the US-North Korea peace process. This is the real problem.

If Japanese people can overcome Abe’s three principles, Japan could move forward at once and open unconditional diplomatic relations with North Korea. If Japan established embassies in Pyongyang and Tokyo, Japan and North Korea could immediately commence negotiations on the nuclear and ballistic missile problem, the sanctions problem, the economic cooperation problem, and the abduction problem. President Barak Obama’s establishment of diplomatic relations with Cuba in 2014 constitutes a good example of such unconditional inauguration of diplomatic relations. Normalization of Japan-North Korea relations would provide a security guarantee to North Korea and provide strong support for both US-North Korean negotiations and US-South Korean negotiations.

If such an ally in Japan appears, then South Korea could negotiate with North Korea and move forward towards true mutual understanding. For that purpose, South Korean people, too, should work to secure the understanding of the Japanese people.

8. A Common House of Northeast Asia

People have long discussed ideas for a regional community in Northeast Asia. In July 1990, I proposed for the first time—“A Common House Where Peoples of the World Live Together”—at a symposium in Seoul hosted by the Dong-A Ilbo (newspaper). In February 2003, newly elected South Korean President Roh Moo-hyun announced his intention to construct a “Northeast Asian Community,” a “community of peace and prosperity.” Encouraged by President Roh’s proposal, I published a book called, “A Common House of Northeast Asia: A New Regional Manifesto” (Tokyo, 2003). All of these plans were sheer products of imagination.

At the beginning of a new era of history, a new positive picture of a regional community must appear. Since 1996, Professor Umebayashi Hiromichi has cherished the idea of a “Northeast Asia Nuclear Weapon Free Zone.” In his thinking, Japan, South Korea, and North Korea could collectively vow neither to produce nor to introduce nuclear weapons in their countries, and the United States, Russia, and China could pledge not to attack one another with nuclear weapons. This is also a product of imagination.

But the situation has drastically changed now. North Korea has its own nuclear weapons, yet has expressed its commitment to the complete denuclearization of the Korean peninsula. Japan and South Korea adhere to the principle of non-possession of nuclear weapons yet are protected by the US nuclear umbrella. Meanwhile, Russia, China, and the United States are all superpowers and are nuclear armed.

So, if the US-North Korea peace process accomplishes the complete denuclearization of the Korean peninsula, the Japanese archipelago, and Okinawa, North and South Korea and Japan would then be denuclearized and neutralized. Such countries can possess regular or minimum military forces, yet not only Japan but also South and North Korea should have an Article 9 in their constitutions. Then, they could form a union of peace states.

They should form a Northeast Asian security community with three nuclear powers surrounding them: the United States, the Russian Federation, and the People’s Republic of China. The three nuclear powers should be united by an oath of non-aggression and non-intervention toward the Korean peninsula and the Japanese archipelago, and no-war with each other. This is the ultimate image of our future Northeast Asia. This is the future that lies beyond the San Francisco System.