|

The South Gate at Beijing University |

Beijing University

A retrospective tour of the haunts and hideouts of the 1989 Tiananmen student uprising would not be complete without a visit to Beijing University, known simply as Beida. Arguably the most prestigious university in China, Beida has long been home to creative thinkers and intellectual ferment ever since the days a young Mao Zedong worked in its associated library and literati such as Hu Shih and Lu Xun graced its grounds.

In 1989 Beida was the fount of discussion and discontent that spread to other campuses. Among Beijing colleges, it was the most distant from Tiananmen, but the Beida contingent always seemed to show up first.

Thirty years ago, I joined a march on Tiananmen from this campus. Later, on the eve of the hunger strike, I got into a heated discussion on this campus about the different dynamics among Beijing’s elite schools. Why was it that students at liberal arts schools, such as Beida and Beijing Normal University got on board the protest train right away, while tech schools, including Beida’s prestigious neighbor, Tsinghua University, were reluctant to join the protests? Was it a matter of campus tradition or did it reflect different intellectual outlooks between those in the arts and sciences?

Beida is a privileged enclave. It has maintained a peaceful facade–the walled-in campus was originally a large imperial garden–but the bucolic tranquility belies a long history of intellectual ferment. It doesn’t look like anyone’s idea of a radical campus, but it is hard to imagine the democracy salons led by astrophysicist-turned-dissident Fang Lizhi in the early months of 1989 taking place anywhere else. When Fang was ejected from his provincial academic home at the University of Science and Technology in Anhui province for political rights agitation, Beida’s august tradition offered sufficient cover for him to continue his efforts there, but at least initially. His freedom to engage students on the topic of democracy didn’t last long, but his fledgling efforts took on international salience when Fang was invited to, and unceremoniously ejected from a Great Wall Hotel banquet hosted by visiting US president, George W. Bush in February 1989.

Student discontent first took flight at Beijing University’s leafy, isolated campus, but the complaints about limited job prospects, bossy party authorities and glaring cases of official corruption were shared by students across the city and country. The youthful Wang Dan, thanks in part to the tutelage of Fang Lizhi, emerged as an early student spokesman, later joined in a leadership triumvirate in Beijing that included Chai Ling and Wuer Kaixi at Beijing Normal University.

|

Card-operated gates at Beijing University in 2019 |

I wanted to spend some time at Beida on the 30th anniversary year of the 1989 protests, but vigilant guards at every entry point thwarted my attempt to visit campus.

I had been forewarned by journalists in early July that the campus was hard to get into, supposedly due to an informal lock-down that went into effect with the first reports of big demonstrations in Hong Kong in July 2019, though I had noticed no upswing in surveillance in the Shida campus which I still visited daily, for coffee in the morning among other things.

As it turned out, I was denied access to the busy South Gate on Haidian Road, a closely-watched portal, but three subsequent attempts to enter quieter side gates did not succeed, either.

|

Haidian Road walkway along south campus wall |

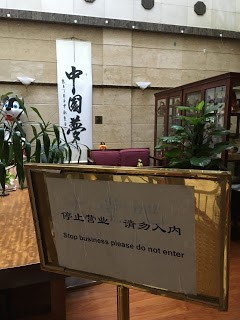

Giving up on the heavily-monitored gates, I decided to search for a “back door” to campus. I had no luck at a small, electronically controlled gate on the west side, but I then entered a hotel that sat astride the campus, thinking indirect entry might be possible via the back door of the hotel, as is the case at the Liyun International dorm at the East Gate of Shida. But that didn’t work either:

“Stop business please do not enter” warned a sign in the lobby.

|

“Stop business please do not enter” |

I went back out and tried a manned gate nearby only to be summarily denied entry with a brusque upraised hand. When I deigned to ask why, the guards glared at me suspiciously, seemingly stunned by the unexpected push back of a question. The two uniformed men standing duty stammered, offering conflicting explanations. Finally an elder colleague intervened, gently explaining that entry could be gained if someone residing on campus came to meet me at the gate. Pondering who I might contact on short notice, I continued my circumnavigation of the walled campus, pausing to rest in the shade near an old gate that no longer serves as a portal but rather a picturesque historic relic.

|

Ancient imperial gate across from West Gate,now a fenced-in |

Beijing University, like Harvard in the US or Oxford in England, is an icon and iconic properties attract visitors. The exquisite garden setting of the Beida campus with its time-worn pagoda and scenic lake is of a piece with the notoriously crowded Summer Palace. Fear of spillover tourist crowding might justify some judicious gate-keeping, but at the time of my visit, on the fortieth anniversary of the Tiananmen massacre and with daily demonstrations in Hong Kong, it seemed that political fears loomed large to the security-obsessed gatekeepers.

I was trying to understand the rhymes and reasons of people being turned away from a campus known as a bastion of free inquiry while watching the half dozen guards doing their thing under the colorfully painted traditional arches at West Gate. I didn’t notice any foreigners seeking entry, but plenty of Chinese were being turned away. Students on foot were directed to the wicket of a secure toll gate where card-holders could enter with a security swipe. Cyclists had to dismount and show ID at another channel.

Built in 1926, West Gate leads directly to Shao Yuan, which has long housed international students, researchers and teachers. The security at the gate was less formidable than the main entrance on the south side of campus, and architecturally, it was a bit of a throwback to the old days of mortar and brick, lacking the metallic railing, electronic wickets and traffic fences of the newer gates. That’s not to say it wasn’t monitored, there were at least half a dozen eagle-eyed gatekeepers checking ID and busy making sure irreverent student cyclists dismounted. Like guards and cops everywhere, a few of them no doubt enjoyed the arbitrary and petty exercise of power, but most of them looked like decent working class boys just trying to get through the day.

I counted six uniformed guards standing between me and my goal of entering the campus. I decided to try my luck, hoping to talk my way in. As I approached the left side of the vermilion gate, the guard took off his hat, paused to wave to his colleagues, three of whom were busy questioning an older man, and took leave of his post. I walked towards him as he walked away; presumably his shift had just ended. I got a curious side-glance from him as we passed each other but I wasn’t stopped.

I walked right in. It’s not that I wasn’t noticed, I certainly stood out, in a big, hulking, indelibly foreign way, but a moment’s inattention allowed me to hide in plain sight. I didn’t stop and no one stopped me. I kept on walking until I was well beyond the gate, entrance secured by chance and the confusion of the moment.

|

Slipping into West Gate |

I surely had not escaped the unblinking gaze of the various cameras mounted on the gate, nor did my escapade escape the gaze of my travel companion, who had duly recorded my unauthorized entry on video that was recorded in the full expectation that I would be turned away.

Once inside the walled compound, I gained a tacit authority, if only by dint of location and the presumption that I must have had permission to be inside. On the inside, one becomes an insider. By crossing the threshold, I underwent a transformation from unauthorized outsider to a person on the inside looking out.

|

The gatekeepers had their backs to me now. Even if I were to encounter guards on campus, the default assumption upon seeing someone inside the premises is that such a person has the right to be inside. What’s more, given the relatively low-stakes game of getting onto a campus, where, unlike a military installation, at least some foreigners had a right of entry some of the time, I was able to use my new-gained authority of being on the inside to bring someone from the outside in. Thus I was able to gain entry of the person who took my picture as I entered the gate, waving him in as my “guest” a short time later. It probably came down to luck, but it’s also a reminder that as strict as things get in China, there are often ways around some obstacles and pockets of lassitude as well.

|

The old Shao Yuan dorm on the “foreign” side of campus |

The Shao Yuan dorm where I had stayed in the early 1980’s looked basically unchanged at first glance. I went straight to the cafeteria where foreign students hungry to practice Chinese at meal time once vied to chat with the harried service staff only to discover it was now a no-frills Chinese student cafeteria without a single foreigner in sight. Corridors where friends once stayed were converted to campus offices.

The foreign action was now next door, in the relatively new foreign student facility that boasted better rooms and higher end dining options, but I was eager to eat in the old dining hall, if only I could.

The problem was that Beida, as other campuses, is largely cashless these days. Students can use their ID cards or phones for most kinds of payment, and sometimes that’s the only way to pay. The new seamless, cashless world of commerce, where all transactions were automatically recorded and subject to monitoring, was not to my liking in principle, but it also posed a practical obstacle to an interloper such as myself, even after securing access to campus.

After ordering up a nostalgic meal at the canteen in which I had once dined, I was turned away, loaded tray in hand. There was no cash option.

A sympathetic Chinese diner understood my dilemma and let me use his card in exchange for cash enough to cover the meal.

|

The old dorm dining hall is now a card-only Chinese eatery |

In 1989, the de facto split between Chinese food halls and food halls for foreigners was maintained by the use of different meal tickets distributed to different campus constituencies. It wasn’t exactly racial Apartheid, and you could get around it with a bit of conniving, but the chit system represented the university administrator’s vision of separate (and unequal) facilities.

Thirty years on, the color-coded paper chit system is gone and strictures have loosened somewhat, but electronic gateways are just as effective at keeping people apart. Short-term foreign visitors are limited to eateries that accept cash. Even foreign students with campus cards still tend to eat and reside in purpose-built facilities for foreigners.

In the mid-1980’s when I was a student I went out of my way to break out of the foreign ghetto, but it came at a price of isolation and inconvenience. Shamelessly relying on “guanxi” (connections), I got permission to stay in a building where Chinese visiting scholars resided, but there was no hot water, let alone showers, and the front door was locked at night earlier than the other dorms.

I remember complaining to a Chinese professor back in the early days that it wasn’t fair to keep foreigners and Chinese in separate dorms and dining halls and he firmly disagreed, saying it was better for everyone that way. “What’s more, you foreigners have more money.”

|

“Western” dining at Beida |

While it was once safe to assume that foreigners had more money than cash-starved Chinese in the days of Mao jackets and bicycles, a fact frequently trotted out to justify the separate and unequal treatment, that is decidedly no longer the case.

Yet even today, foreign students and scholars are kept at arm’s length, expected to conduct their campus lives in parallel to the rest of the student body. The tacit separation is sweetened with entitlement, owing to dueling Chinese concepts of treating guests well and raking in the cash, foreigners get better dorms, typically two to a room, while Chinese still endure dorms with bunk-beds and six to eight students per room. The Liyun foreign student apartments at Beijing Normal even include hotel-type single rooms with air-conditioning and private bathrooms.

But the old assumption that foreigners were rich and Chinese were poor simply doesn’t hold up any more. If anything, the pendulum has swung the other way, but informal segregation of facilities remains the norm, suggesting that it was never just about economics.

At Beijing Normal, the economical Chinese food halls also require a campus card, but the food at the Japanese dining facility and other “foreign” dining options may be purchased with cash.

One historical reason for segregated facilities was communist party paranoia about foreign influences, running the gamut from “spiritual pollution,” and inter-racial dating to espionage. But the legacy of suspicion lives on; a Chinese college campus is a laboratory of social control from the moment one enters the gate.

Today cameras take the place of the plainclothes minders who had an out-sized role to play on campus in the old days, but it’s a toss up as to whether it’s preferable to be watched on camera or in person.

Either way, one can never entirely escape the sense of being watched, even when no one is watching. Evading snooping eyes and idle ears is a default way of life in China. In the 1980’s the personal was as much a target of surveillance as the political, at least it felt that way when it was all eyes on the foreigner.

In 1983, while enrolled at East China Normal University, I got arrested upon arrival at Xian train station after a day’s journey from Shanghai because I booked the trip without the requisite permission from the foreign student office. My misadventure is described in Runaway Train.

These days, the monitoring of lifestyle choices is considerably more relaxed but the policing of politics has not relaxed, and may even be getting more intense. Phone monitoring provides not just real time geo-location but troves of intimate data and personal communications.

There are still plenty of vigilant neighborhood aunties and idle busybodies, but technology plays an increasingly important role in keeping things under wraps. It is not uncommon in public places to see monitors, such as the Beida dining hall scene shown below, a not-so-subtle reminder that very little activity takes place without witness, electronic or otherwise.

|

Dining hall monitor screen at Beijing University |

Complaints about unequal treatment of foreigners and locals were never far from the surface in 1989 so it was interesting to see that the playing field has not so much been leveled as fenced off into two separate playing fields.

The historic hunger strike famously started on this campus, a brilliant stroke of strategy, which transformed the demands of non-conforming but generally well-off students into a higher calling that people in all walks of life could sympathize and relate to. The strikers convened in a small Chinese dining hall, the sort of place where plain food and noodles were served but it took on significance as the scene of an overly-dramatized “last supper” as strikers partook of their last meal before setting out on a march to the square.

|

Cash and cake in an upscale “Western” café on campus |

Failing to locate the old noodle joint, I took a seat in the “foreign” cafe, but eschewed the “GREAM FRUIT CAKE” being promoted at every table. The price of the cream cake per slice was hard to determine, but running as high as 79 RMB per pound, it was not cheap.

I’m sure it was delicious, but seeing as it was sold by the pound and I had come to remember the hunger strike, I settled for a glass of hot water and a few curious stares.

|

Here cake is sold by the pound |

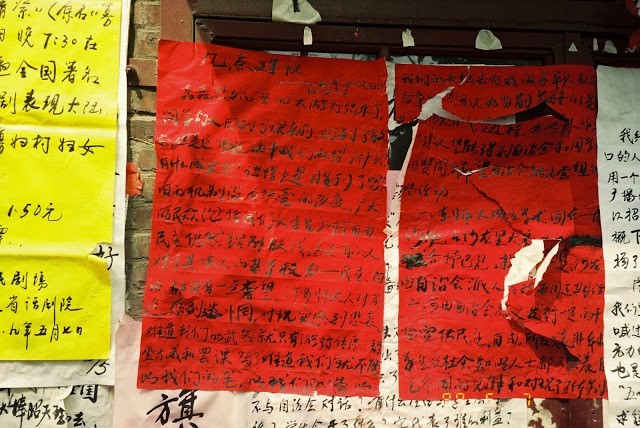

From Shao Yuan I walked to the center of campus, past the basketball and tennis courts to the dorm closest to the traditional campus meeting spot, a small, hemmed in intersection known as the Triangle, where big character posters charting the evolution of student demands were once posted. I had spent time studying those posters with university friends and had later hung-out there with Chai Ling and other student leaders for clandestine meetings. On campus, as elsewhere, there was considerable cat-and-mouse intrigue between authorities and rebel students keen to evade detection. Student watchmen and bodyguards were part of the mix.

The dorm overlooking the Triangle has been remodeled, but it was still as non-descript as before. What made ordinary, indeed outright shabby dorm buildings crackle with excitement and intrigue in 1989 was the conspiratorial conversation, the incessant noise of the jerry-rigged student speaker system and sometimes combative mood of the moment that allowed unadorned dorm rooms to function as a hidden HQ for the student siege of the square

The Triangle, known as “sanjiaodi” in Chinese, is a little campus intersection I have enjoyed revisiting over the years, though on my most recent visit it bore almost no resemblance to its humble origins as a crack in the campus fabric where ideas could be readily exchanged, more of a dusty lot than Hyde Park, but imbued with a history of free speech.

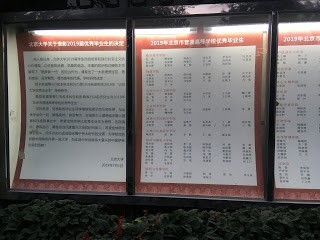

The demolition of the low-rise brick building along the famous hypotenuse has altered it’s fabled narrow contours, for one, and needless to say, what signage there can be seen today is a far cry from the free-for-all free expression that flourished in 1989. Instead, a long, sterile neon-lit signboard is under lock and key, controlled by university authorities.

|

Bulletin boards by Sanjiaodi today |

|

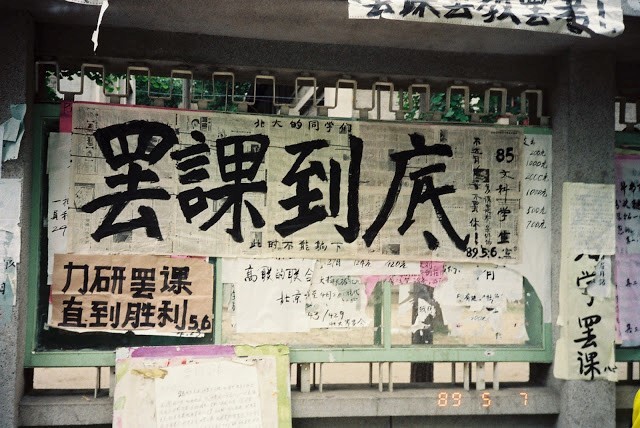

As I wrote in my book Tiananmen Moon, the Triangle was an obligatory stop during the groundswell of student unrest in 1989. It was here one could learn the latest direction of student thought and action, though conflicting views were evident and yesterday’s bulletins papered over by today’s. One night early in the protest season, I was hanging out with Cui Jian and some other musicians at the Jianguo Hotel. We watched TV in vain, looking for updates on the possibility of “dialogue” between students and the state. Frustrated with the non-news news, we piled into an old jalopy and drove clear across town to read the latest news in the form of hand-painted posters and scribbled sheets attached to the democracy wall of the Triangle.

|

Student signboard at the Triangle announcing plans for all-out strike in 1989 |

|

Dorm wall plastered with posters in 1989 |

As I made my way down the tree-lined Wusi road, mercifully free of cars, songs of the eighties echoed in my mind, both the plaintive melodies of Theresa Teng’s tender love songs and the driving rhythms of Cui Jian’s gruff ballads, all evocative of a place and time indelibly tied to the past.

Some of the old dorms where activism had once thrived were derelict, weed grown and boarded up, presumably awaiting the developer’s ax, but the modest brick buildings that served as faculty dorms just south of the Triangle looked unaltered and were intact, still inhabited. The narrow stone balconies of the teachers’ residences were just as I remembered, still vivid in my mind because on the day of a big march to Tiananmen, faculty made a show of enthusiastic support for the students from those very balconies, waving and cheering from above.

|

Old dorm slated for demolition |

Retracing the steps I took with thousands of other anxious demonstrators, I went from the campus democracy wall at the Triangle to South Gate. The open promenade between the two had served as the staging ground for the big demonstrations, including the bicycle demonstration of May 10, 1989.

|

The South Gate staging ground for the May 10, 1989 rally |

Dubbed the march of “ten-thousand bicycles” (not much of an exaggeration) the mass procession offered a fleeting tour on wheels of Beijing at a time of unrest, uncertainty and fears of a crackdown. The big marches of late April and early May were over, the hunger strike had yet to begin. It was a kind of filler, a fun diversion, a move to keep moving at a time when no one had a clue as to what was to come next.

The spirited procession began at Beijing University, exiting the south gate to cheers from faculty and student supporters, and boldly swept east down the street, a contingent of perhaps a thousand until new recruits were picked up along the way, passing Renmin University, Zhengfa University and finally, last, and most significantly, Beijing Normal University, the campus closest to Tiananmen Square, where the contingent was big and the bicycle traffic jammed up as far as the eye could see.

|

Bicycles filled the road as far as the eye could see |

|

Bus passengers wave in support despite traffic slowdown |

The May 10, 1989 rally circumnavigating Beijing was an endurance test, long and tiring, the thud of soft collisions and tinkle of countless bells ringing the whole way, but it had its thrilling and exhilarating moments. Crowds appeared out of nowhere to wave, gesticulate and heartily greet the procession. Townspeople, curious and inspired, lined up on both sides of the road at key junctures. The most intoxicating moment was racing across Tiananmen Square in defiance of police orders to the cheers of an instantly assembled crowd.

|

The demonstration on wheels reaches Tiananmen |

Conjuring up images of the past, pondering continuity and change, I now stand at Beijing University’s south gate, gazing at the modern high-rises in the distance. So much has changed, so many parts of Beijing are unrecognizable. It’s somehow reassuring to see that Beijing’s premier campus is still architecturally conservative, a bit neglected and behind the times, still in keeping with its past. It’s a big enough campus that bicycles are still a thing, although one enters busy thoroughfares outside the gates at one’s peril. Motorcycles and electric bikes have a significant presence on campus as well, but cars are mostly kept out.

|

It feels good to be on campus communing with the past. The same guards who fiercely turned me away just hours before pay me scant heed now as I snap pictures of the gate and city-scape beyond.

|

South Gate as seen from inside |

|

Haidian, the so-called Silicon Valley of China |

Just beyond the traditional rooftops of the idyllic, sequestered campus, stands the spanking new skyline of Haidian, dubbed China’s Silicon Valley. It’s a short distance away, located just across the cavernous motorway of the Fourth Ring Road, but might as well be another world.

Being inside campus one gets a sequestered feeling, and there’s comfort in that given the automotive chaos and non-stop construction in the outside world.

I choose not to exit at South Gate, but turn around and walk the length of campus until I reached the shores of tranquil No-name Lake and its attendant pagoda.

|

Pagoda at Weiming Lake |

Beida at its best is rooted in the past, which is not to say it is not forward-looking, but it is grounded and cognizant of tradition and ways of thinking that may not always find ready reception outside its gates. Its well-preserved corners cultivate an appreciation for the past, but it is also an enclave where various ideas for the future can be worked out without undue pressure from the dictates of the present.

|

Weiming Hu, the beloved “lake with no name” |